Unilateral eosinophilic cellulitis leading to implant extrusion after bilateral enucleation in a dog

Funding information

No funding was obtained in conjunction with this manuscript

Abstract

A mixed breed dog underwent bilateral enucleation with orbital implant placement for secondary glaucoma. Subsequent unilateral implant extrusion occurred. An orbital mass histologically consistent with eosinophilic cellulitis was discovered. It may have developed secondary to communication between orbit and skin. Inflammatory processes mimicking neoplasia can cause implant loss post-enucleation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enucleation is indicated in dogs for conditions in which the eye is painful, and other treatment options are no longer feasible.1 Silicone orbital implants may be placed at the time of enucleation for improved cosmesis, as they prevent overlying tissues from sinking into the orbit as healing occurs.2 Implants are considered contraindicated when neoplastic, infectious, or inflammatory processes involve the orbit.1 Complication rates reported in the literature for orbital implant placement in dogs range from 1% to 6.5%.2, 3 Documented complications include implant extrusion or movement, orbital or incisional infection, and incisional dehiscence.2, 3

Here, we present the case of a 4-year-old neutered male mixed breed dog that underwent bilateral transconjunctival enucleation with silicone orbital implant placement due to uncontrolled glaucoma occurring secondary to uveodermatologic syndrome (UDS). Two months later, he developed a partial dehiscence of the left incision site. Surgical exploration of the site revealed that the implant was no longer within the orbit, which was instead occupied by a firm mass of the same approximate dimensions as the previously placed implant. Histopathology of this mass revealed a marked eosinophilic and neutrophilic cellulitis with granulation tissue. This inflammatory lesion is believed to have caused extrusion of the implant.

2 CASE REPORT

2.1 Clinical history

A 4-year-old castrated male mixed breed dog was referred for evaluation of an open wound overlying the left orbit (Figure 1). Two months prior, he had undergone bilateral transconjunctival enucleation for UDS and secondary glaucoma at another clinic. The dog had never displayed dermatologic signs of UDS. Prior to surgery, he had been treated with oral mycophenolate and topical anti-inflammatory and anti-glaucoma medications.

Silicone implants were placed in both orbits at the time of surgery (size not specified in record; Jardon Eye Prosthetics, Inc.). No contouring or shaping of the implants was performed. Closure of deep fascial layers was achieved with 5-0 polyglactin suture (Vicryl, Ethicon) in a continuous pattern, with interrupted cruciate sutures of 5-0 nylon (Ethilon, Ethicon) used to appose the skin. Oral mycophenolate was discontinued at the time of surgery, and a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanate (12 mg/kg q 12 h; Clavamox, Zoetis) was prescribed. Skin sutures were removed 14 days after surgery, at which time both incisions appeared to have healed normally. Histopathologic evaluation of the enucleated globes subsequently confirmed the clinical diagnosis of UDS with secondary glaucoma.

Approximately 2 months after the original surgery, marked swelling of the left periorbital region was noted with subsequent development of a draining tract. The family practice veterinarian prescribed oral cefpodoxime (6.8 mg/kg q 24 h, Simplicef, Zoetis) and referred the dog for further evaluation and potential surgical management.

2.2 Examination and treatment

On presentation, an open wound of approximately 7 mm in length producing serosanguineous discharge was noted at the midpoint of the incision overlying the left orbit (Figure 2). The contralateral (right) incision was well apposed and appeared to have healed appropriately, and a silicone implant could be palpated in the right orbit. Palpation of the left orbit revealed a firm spherical structure of approximately the same size as the contralateral prosthesis. The dog was preliminarily diagnosed with partial incisional dehiscence with potential accompanying infection and/or suture reaction. Implant extrusion was not suspected at the time. A plan was made for surgical exploration of the area, with removal of the implant and sampling for bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Preanesthetic general physical examination and point-of-care bloodwork were unremarkable. Hydromorphone (0.1 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.03 mg/kg) were administered via intramuscular injection to enable intravenous catheter placement and subsequent induction of general anesthesia. Following this injection, the dog vomited. A black spherical object consistent in appearance with a silicone orbital implant was found in the vomitus. Because the appearance of the incision had not changed (i.e., no hemorrhage or enlargement of the region of dehiscence was noted), the implant was believed to have been released from the stomach during vomiting, rather than extruding as a result of increased orbital pressure secondary to vomiting.4 In addition, when palpation of the left orbital region was repeated, the same firm spherical structure could still be felt within the orbit.

Anesthesia was induced using intravenous propofol administered to effect. The dog was intubated and maintained on isoflurane throughout the procedure. Cultures were obtained from the draining tract. The region surrounding the incision was then clipped and prepared with dilute povidone-iodine solution. An elliptical incision was made around the previous incision using a #15 blade. Tenotomy scissors were used to enter the orbital space using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection. An approximate 2 cm firm pinkish-white mass was noted filling most of the orbital space. The mass was dissected free using tenotomy scissors and removed en bloc with the peri-incisional skin. Additional cultures were taken from the orbit, which was then thoroughly flushed with balanced salt solution. Deep tissues were closed with 4-0 polydioxanone suture (PDS, Ethicon) in a continuous pattern, with continuous subcuticular sutures of the same material. Skin was apposed with 4-0 polypropylene suture (Prolene, Ethicon) in a cruciate pattern.

The mass was bisected to rule out a retained surgical sponge (gossypiboma). No foreign material was evident on gross inspection (Figure 3). The mass was then immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and submitted for histopathologic evaluation. Differential diagnoses at that point included neoplasia or an infectious or inflammatory process such as a granuloma.

2.3 Outcome and follow-up

The dog was discharged from the hospital with oral meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg q 24 h; Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim), gabapentin (6.8 mg/kg q 8–12 h), and cefpodoxime (6.8 mg/kg q 24 h). External sutures were removed 14 days after surgery and healing proceeded without further complication. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures yielded no bacterial growth.

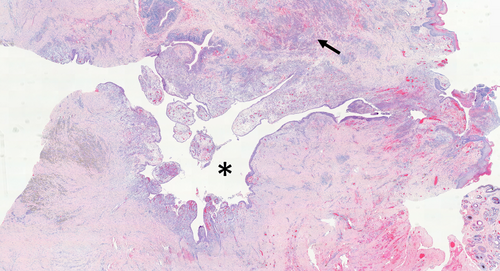

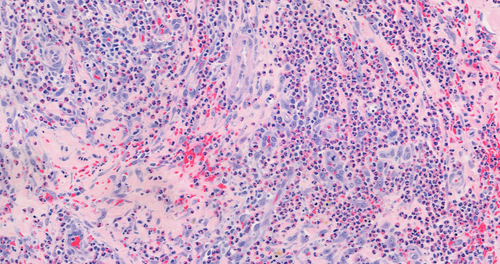

Histopathologically, the mass was comprised of abundant collagenous stroma intermingled with bundles of skeletal muscle undergoing degeneration, with significant infiltration of eosinophils and neutrophils throughout the sample (Figures 4 and 5). Smaller numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages were scattered throughout the mass, with regions of hemorrhage and necrosis also present. A deep fissure in the center of the mass was lined by variable thickness stratified squamous to columnar epithelium with subjacent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate; smaller enclosed epithelial-lined areas with similar surrounding infiltrates were also present. No foreign material was seen. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections were evaluated and revealed no infectious organisms. A diagnosis of severe, diffuse eosinophilic and neutrophilic cellulitis with granulation tissue formation and fibrosis was made.

3 DISCUSSION

Enucleation with silicone orbital implant placement is a commonly performed procedure in dogs. Complication rates are low, and implant extrusion is rare but has occasionally been documented.2, 3 Neoplastic or inflammatory orbital processes have led to implant extrusion or displacement in dogs, cats, horses, and people,2, 3, 5, 6 although to our knowledge this is the first report of implant extrusion secondary to an apparently sterile inflammatory mass lesion in a dog.

The marked eosinophilic inflammation in the mass was unusual and not consistent with the majority of orbital inflammatory or infectious processes previously described in dogs, such as abscesses, extraocular myositis, toxoplasmosis or neosporosis, or histiocytic disorders.1, 7-12 Eosinophilic myositides of the head have been documented in dogs, but the muscle fibers present in this lesion were sparse and did not seem to be the focus of the inflammatory response.13-16 Orbital granulomas associated with Onchocerca spp. in dogs may contain eosinophils, but this lesion lacked other features of a granuloma, and no nematodes were found within the tissues.17, 18 Canine eosinophilic dermatitis shares some histopathologic but not clinical features with the lesion noted in this dog, while canine and human eosinophilic granulomas share clinical features but differ histologically.19-23

Clinical and histopathologic findings in the dog of this report suggest several potential alternative mechanisms for the massive eosinophilic inflammatory response seen. Eosinophils have conventionally been linked with Th2-type immune responses, produced primarily in the context of parasitic infections or allergy.24, 25 Hypersensitivity or foreign body reaction to the silicone implant or to suture or microscopic gauze fragments thus may have served as a trigger. Silicone is typically considered highly biocompatible and nonallergenic, although it has been linked, somewhat controversially, to autoimmune syndromes in humans.26 Suture, gauze fragments, and other surgical debris have been implicated in orbital mass lesions in people, but histopathology from those lesions is usually characterized by the presence of giant cells and classical granulomas, both of which were lacking in this patient.27-30 While no foreign material was evident either grossly or microscopically, it is still possible that gauze fibers, resorbing polyglactin suture, or debris associated with the implant were present and were not captured during sectioning or were lost when the implant was extruded.

However, recent work has suggested a more complex role for eosinophils in both Th1 and Th2 immune responses and has shown that activated neutrophils can promote eosinophil migration, particularly when lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) is present.25 The epithelialized cleft seen in this mass suggests there may have been communication between the skin surface and the orbit prior to the onset of swelling and incisional dehiscence, possibly due to epithelial downgrowth or focal incarceration of skin or remnant conjunctiva into the incision at the time of original closure. This communication may have permitted low-level orbital infection and potentially biofilm formation on the surface of the silicone implant, which may have in turn triggered an inflammatory response. Bacteria were not seen on histopathology, and bacterial cultures yielded no growth; however, the dog had been receiving systemic antibiotics for almost a week prior to orbital exploration and mass excision.

Finally, the dog of this report had received a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of UDS, and systemic immunomodulatory treatment had been discontinued following enucleation. Although the dog had never been noted to have dermatologic manifestations of UDS, it is possible that underlying autoimmune disease played a role in development of the eosinophilic inflammatory orbital lesion. UDS has been classified as a Th1 response, but ocular lesions may display Th2 characteristics as well.31, 32

4 CONCLUSION

Orbital implant extrusion following enucleation is rare in dogs. This report adds a further case to the literature. In the dog of this report, a mass lesion led to implant extrusion. Orbital mass lesions are often presumed to be neoplastic. Histopathologic findings in this case serve as a reminder that orbital inflammatory processes can sometimes produce mass lesions that mimic neoplasia. Care should be taken during enucleation procedures to achieve good incisional apposition to limit the potential for communication between the orbit and the skin surface.

ACKNOWLEGEMENT

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Riley J. Aronson, Stephanie A. Pumphrey, and Nicholas Robinson contributed to acquisition and evaluation of case material and drafting, revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This case report and the patient care described therein conform to institutional ethical guidelines. Permission was granted by the owner of the dog described for publication of this case report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.