Healthcare providers' expected barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centered long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors: A PanCareFollowUp study

Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer survivors face high risks of adverse late health effects. Long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors is crucial to improve their health and quality of life. However, implementation remains a challenge. To support implementation of high-quality long-term follow-up care, we explored expected barriers and facilitators for establishing this follow-up care among healthcare providers from four European clinics.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted using four focus groups comprising 30 healthcare providers in total. The semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the Grol and Wensing framework. Data was analyzed following a thematic analysis, combining both inductive and deductive approaches to identify barriers and facilitators across the six levels of Grol and Wensing: innovation, professional, patient, social, organizational and economic and political.

Results

Most barriers were identified on the organizational level, including insufficient staff, time, capacity and psychosocial support. Other main barriers included limited knowledge of late effects among healthcare providers outside the long-term follow-up care team, inability of some survivors to complete the survivor questionnaire and financial resources. Main facilitators included motivated healthcare providers and survivors, a skilled hospital team, collaborations with important stakeholders like general practitioners, and psychosocial care facilities, utilization of the international collaboration and reporting long-term follow-up care results to convince hospital managers.

Conclusion

This study identified several factors for successful implementation of long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors. Our findings showed that specific attention should be given to knowledge, capacity, and financial issues, along with addressing psychosocial issues of survivors.

1 INTRODUCTION

The number of childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) is increasing. Currently, the estimated population of CCSs in Europe is approximately 500.000.2 CCSs face a high risk of developing adverse late health effects due to their cancer history and treatment. These late effects are heterogeneous, occurring on the physical, psychological, and social level3-15 and lead to higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to age and sex-matched controls.12, 16-21 The quality of life of CCSs is often affected by late effects,4-7, 17 emphasizing the necessity for long-term follow-up care (LTFU) to improve CCSs' health and quality of life.6, 22, 23

Due to the heterogeneity in incidence, type, and severity of late effects, a person-centered multidisciplinary care model is necessary to guide the organization of LTFU care for CCSs.24 High-quality LTFU care is based on evidence-based guidelines for screening and surveillance of late health effects after cancer treatment and person-centered care.22, 25-29 Despite the available literature on evidence-based (models of) LTFU care, sustainable implementation remains a challenge.30-34 The majority of the European CCSs still has limited access to high-quality LTFU care.35

To enhance implementation of LTFU care for CCSs in Europe, the PanCareFollowUp (PCFU) consortium, established in 2018, developed the PCFU Care intervention based on a Dutch LTFU care model.1, 24 The overall aim of the intervention is to empower childhood cancer survivors across Europe and to improve their health and quality of life by providing person-centered survivorship care.1 The PCFU Care intervention will be evaluated through a prospective cohort study conducted at four pediatric cancer-focused LTFU care clinics, each representing different healthcare systems with varying levels of pre-existing survivorship care implementation.1, 36

However, most innovations do not implement themselves. Tailored implementation strategies have the potential to improve implementation efforts.37 Identifying barriers and facilitators is a critical first step in developing an effective implementation strategy.38 Existing reviews on barriers and facilitators for implementing LTFU care for cancer survivors mainly focused on adult cancer survivors and specific cancer types.33, 34 Barriers and facilitators are insufficiently studied in the context of establishing LTFU care for the heterogenous population of CCSs. Therefore, we performed a pre-implementation study aiming to explore expected barriers and facilitators for the implementation of the PCFU Care intervention among health care providers (HCP) involved in LTFU care for CCSs in four European clinics.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and setting

A qualitative study was performed using semi-structured focus groups with HCPs to explore potential barriers and facilitators for the implementation of the PCFU Care intervention. This study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ checklist)39 and adhered to local medical ethical standards of the participating centers.

As part of the European-wide PCFU project (Horizon 2020 grant), this study included four European LTFU care clinics for CCSs, located in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Italy.

2.2 PCFU Care intervention

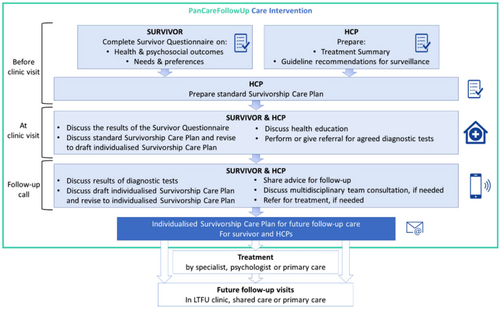

The PCFU Care intervention is based on international guidelines for surveillance on late effects and person-centered care. The organizational structure for person-centered is based on the pillars of Eckman et al.25 and consist of three phases; initiating, integrating and safeguarding a partnership between patients and HCPs. The first phase of the PCFU Care Intervention, involving the initiation of a partnership between CCSs and HCPs, takes place before the clinic visit. During this phase, both CCSs and HCPs prepare the clinic visit by completing a questionnaire (the survivor questionnaire) and a treatment summary, respectively. The survivor questionnaire is web-based and gathers information about the CCSs' health, well-being, medication use, medical and family history, lifestyle, social situation, healthcare needs, and preferences for care with their HCP.1 The second phase, concerning integration of this established partnership between CCSs and HCPs, involves discussing the CCSs' health and follow-up care based on shared-decision making, during the clinic visit. Lastly, this partnership is safeguarded by a follow-up call during which the results of diagnostic tests and recommendations for further follow-up care are discussed. These results and recommendations are summarized in a survivorship care plan. Figure 1 shows the important steps within these three phases. The development and features of the PCFU Care intervention are described elsewhere.1

2.3 Study population

A purposive sampling strategy was applied to recruit participants for this study. At each of the four centers where the PCFU Care intervention will be tested for feasibility, we aimed to organize one focus group with a minimum of five HCPs per group. HCPs from the participating clinics involved in LTFU care were invited by local representatives of the PCFU project. HCPs that were willing to participate registered via e-mail.

2.4 Data collection

On-site focus groups were conducted in Belgium, the Czech Republic, and Italy between September 2019 and November 2019. Due to pragmatic reasons, a video conference application was used for Sweden. Focus groups in Sweden and the Czech Republic were conducted in English and focus groups in Belgium and Italy were conducted in their native language. Two independent experts in qualitative research and implementation research conducted the focus groups, with a note-taker present. Prior to the focus groups, participants were informed about the study and had the opportunity to ask questions. Subsequently, participants signed informed consent and completed a demographic questionnaire containing background information such as sex, age, and profession. The participants did not receive any incentives for participation.

To identify potential barriers and facilitators for the implementation of the PCFU Care intervention, a semi-structured interview guide was developed based on the theoretical framework of Grol and Wensing.38 This framework (Table 1) describes barriers to and incentives for change, that can influence the implementation of interventions in the medical field, at six levels of healthcare (innovation, individual professional, patient, social context, organizational context, economic and political context). The interview guide incorporated open-ended questions on (1) current follow-up care; (2) differences between current care and care according to the PCFU Care intervention; (3) HCPs' opinion of the PCFU Care intervention; (4) expected barriers and facilitators for implementation of the PCFU Care intervention in general and according to the six levels of Grol and Wensing and (5) needs for successful implementation of the PCFU Care intervention.

| Healthcare level | Innovation | Individual professional | Patient | Social context | Organizational context | Economic and political context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers and facilitators |

Advantages in practice Feasibility Credibility Accessibility Attractiveness Clarity |

Awareness Knowledge Attitude Motivation to change Behavioral routines Skills Feelings |

Awareness Knowledge Skills Capability Attitude Compliance Motivation Feelings Behavior Preference |

Collaboration Opinion of colleagues Culture of the network Leadership Environmental support |

Organization of care processes Staff Capacities Resources Structures |

Financial arrangements Regulations Policies |

2.5 Data analysis

Data from focus group interviews were audio-recorded, anonymized, transcribed verbatim, and the Italian focus group was translated into English. Three researchers coded each transcript independently. Discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. A thematic analysis was performed using Atlas.ti 22.0.11 for Windows. The analysis consisted of an inductive approach followed by a deductive approach. The inductive approach started with open coding of transcripts on a sentence level. Subsequently, axial coding was used to cluster open codes into categories. The emerged categories were deductively mapped on the levels and domains within the theoretical framework of Grol and Wensing. New categories were added to the framework. Representative quotes were selected from the transcripts.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

Thirty HCPs participated in four focus groups at the LTFU care clinics for CCSs. Table 2 provides the participants' demographics. HCPs had a mean age of 51 years, 67% were female and they had 24 years of working experience on average. Group sizes within the four focus groups ranged from five to 12 participants.

| Demographics of Healthcare Providers participating in the Focus Group Discussions (n = 30) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years mean ± SD | 50.5 ± 11.4 |

| Sex, female n (%) | 20 (66.7%) |

| Occupation | |

| Medical Doctor | 19 (65.5%) |

| Nurse | 5 (17.2%) |

| Other healthcare professions (pediatric oncology counselor, psychologist, physiotherapist) | 5 (17.2%) |

| Unknown n (%) | 1 (3.3%) |

| Experience | |

| Working experience, years mean ± SD | 23.8 ± 11.7 |

| Working experience in long-term follow-up care, years mean ± SD | 18.1 ± 12.7 |

| Number of survivors seen per month during consultations | 42.6 ± 45.4 |

3.2 Barriers and facilitators for implementation of the PCFU Care intervention

Tables 3 and 4 present the identified barriers and facilitators according to the six levels of Grol and Wensing. Most barriers and facilitators were identified on the organizational level. The results section elaborates on barriers and facilitators that were mentioned during at least two of the four focus group interviews. These are in bold within Tables 3 and 4.

| Innovation level | Individual professional level | Patient level | Social context level | Organizational level | Economic and political level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Feasibility

Attractiveness

Clarity

|

Knowledge

Skills

Motivation

Feelings

|

Capability

Compliance

Feelings

Behavior

|

Collaboration

Environmental support

Opinion of colleagues

|

Capacity: Time, staff, resources

Organization of care processes

Structure

|

Financial arrangements

Policies

|

- Note: Barriers in bold were mentioned during at least two of the four focus group interviews.

| Innovation level | Individual professional level | Patient level | Social context level | Organizational level | Economic and political level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Advantages in practice

Attractiveness

Credibility

|

Knowledge, awareness

Skills

Attitude

Motivation

|

Knowledge, awareness

Motivation/compliance

Preference

|

Collaboration

Culture of the network

Opinion colleagues

|

Capacity: Time, staff, resources

Organization of care processes

Structure

|

Financial arrangements

Regulations

Policies

|

- Note: Facilitators in bold were mentioned during at least two of the four focus group interviews.

3.3 Innovation level: PCFU Care intervention

3.3.1 Barriers

That it is a minimum, the questionnaire is still a blank sheet of paper with many questions that cannot be discussed in some way, so for me this is a barrier, the questionnaire. I cannot specifically foresee this questionnaire, I fear that, compared to my experience with patients, the questionnaire is a bit impersonal, and therefore a barrier.

However, the questionnaire was also viewed as an attractive tool when well-supported by a clinic visit and a good survivor-HCP relation.

3.3.2 Facilitators

This [the survivor questionnaire] is to kick off the discussion […] Because if we can focus on what they have marked as “I'm very concerned” I think we meet them in the correct arena. We can start with other things, but I think by doing this we have a greater chance of hitting what they really believe is important. And we really give them a chance to think before they come to the visit, to think over their situations.

3.4 Professional level

3.4.1 Barriers

The training for specialists on the territory that in my opinion is absolutely lacking with particular regard to the adult world, because many are still linked to the concept of being cured and not long surviving, therefore with an underestimation of the risks of patients that in my opinion is still in place.

3.4.2 Facilitators

It's a moral obligation if you treat people when they're children and adolescents that you take care of them when they're adults.

3.5 Patient level

3.5.1 Barriers

With brain tumor survivors, you have to pay attention. There are a couple that cannot fill in the [survivor questionnaire]. Half of them cannot fill in the questionnaire.

It becomes very difficult, also because, let's face it, the trust of these patients in local centers is close to zero, especially with regard to their pathology and their previous tumor disease, etc., they don't trust anymore. So we have a lot of work to do from a cultural point of view, not only with doctors, but also with patients, and that would be a lot…

3.5.2 Facilitators

The vast majority have filled this [the survivor questionnaire] in and bring it with them.

Providing additional support for survivors who have been lost to follow-up in LTFU care or for those who may find the questionnaire demanding, was seen as a facilitator for their compliance with the PCFU Care intervention.

3.6 Social context level

3.6.1 Barriers

The connection with the territorial facilities on these mental and psychosocial health aspects is absolutely null, because these are particular patients who sometimes do not have pure psychiatric disorders, but have reactive syndromes, rather than from employment, social, economic, sentimental point of view, they are behind, and no one takes charge of these needs.

This means that survivors' psychosocial needs may not be adequately addressed, despite the high demand for psychosocial care among the survivor population. Another potential barrier mentioned by HCPs was the uncertainty whether survivors who face difficulties with completing the survivor questionnaire or attending the LTFU clinic, have the opportunity to receive environmental/family support to assist them.

3.6.2 Facilitators

There is plenty of collaboration from all the specialists, we are organised for the most serious complications, and we have good cooperation in such different fields even with adult experts.

Having such prominent collaborators like cardiologists here is another facilitator. Because we need to work on different levels to have internal medicine people who will focus on […], for example cardiovascular risk. That's something we have the common goals, like oncologists and cardiologists because we foresee some troubles in our survivors being 50 years old.

3.7 Organizational level

3.7.1 Barriers

HCPs mentioned a lack of time and staff for various components of the PCFU Care intervention. Specifically, time limitations were expected for the survivor questionnaire procedures, such as processing the questionnaire results before the clinic visits. Moreover, the treatment summary was seen as a time-consuming process. HCPs also indicated the challenge to both treat acute cancer patients and take care of survivors in terms of available capacity. Due to limited capacity, acute care is often prioritized over LTFU care. In the future, an increasing number of survivors will be seen at the LTFU clinic. The lack of staff, resources, and care facilities were major barriers for sustainable implementation.

We have different types of patient records, so, in the most of our area we can read the results, it is just one same system, but then there are also three more that are totally different and don't communicate. So, you rely on papers and papers being scanned and so. That is how the systems are, there are different healthcare providers who don't really speak electronically to each other. So if I would point out a possible barrier then it is still the communication with the three other regions which work with different communications systems and send you the patient data if they send it to you at all via paper or via post mail.

We prevent the second tumor, we make them responsible for their project of care and life, but then instead all the psychosocial aspects that we identify, a treatment has not been thought through. On the field there are no structures to welcome them, there are no paths, there is no specific training, because either they are placed in the melting pot of adult psychiatric patients, and there is no response to their needs, or the problem is underestimated, and then they are left to themselves.

3.7.2 Facilitators

We're recently well-staffed for doctors, I would say. There are four at least at the department of oncology and two in the department of pediatric oncology.

We have excellent secretaries that support us in such a good way.

We have since two, three years now [an occupational therapist].

I think it's optimal. If you can have somebody [a nurse] but with the skills. It's not any nurse. It's a nurse with the skills. I mean, you can train somebody, but [our nurse] comes with the knowledge of […] having worked with these patients already at the department of endocrinology on all the late effects associated there. So, we were blessed to have somebody who comes fully equipped from the beginning.

Furthermore, the alignment of organizational structures and operating procedures with the elements of the PCFU Care intervention would facilitate its implementation. An organized structure would support efficient management of medical and psychosocial needs for CCSs.

3.8 Economic and political level

3.8.1 Barriers

We have patients who also come from outside the region, therefore they have to face expenses both in terms of travel and stay in the hospital facilities, therefore high costs that are not always reimbursable, and so also then especially with regard to the group of adults and young adults, even lost days of work, so this type of organization it is a barrier.

HCPs mentioned the uncertainty of long-term financial resources for LTFU care as a barrier to achieve sustainable implementation.

3.8.2 Facilitators

Hammering on the authorities to make them understand that this is an issue. And there it's always good to have the numbers. It's always good to have the numbers to be able to say, There are this many people, they are these ages, they have such and such issues, we see them at this and that regularity. And I think the only thing that will affect someone sitting on the money and on the resource is being convinced by numbers, by data. Yeah, and try to calculate the health economics about it.

Additionally, financial aid for survivors was expected to facilitate their participation in LTFU care.

4 DISCUSSION

This study presents the first qualitative pre-implementation study exploring barriers and facilitators for implementing high-quality LTFU care for CCSs from the HCPs' perspective in four LTFU care clinics in Europe. Barriers and facilitators were identified within all six levels of the Grol and Wensing framework. Most barriers were identified on the organizational level, including insufficient staff, time, capacity, and psychosocial support. Other main barriers included limited knowledge of late effects among HCPs outside the LTFU care team, inability of some survivors to complete the survivor questionnaire and lack of (long-term) financial resources. Main facilitators included motivated HCPs and survivors, skilled hospital team, collaborations with important stakeholders like GPs and psychosocial care facilities, utilization of the international collaboration and reporting LTFU care results to convince hospital managers.

The potential implementation challenges lack of time, staff, and (ICT) resources have been previously mentioned by HCPs for implementing LTFU care.33, 40, 41 As potential implementation strategies to mitigate these barriers, establishing efficient organizational structures that incorporate collaborative ICT systems (e.g., automatic data generation from electronic medical records, treatment summary databases, web-based survivor care plans) could be considered.31, 41-43 In addition, contracting specialized survivorship nurses, administrative staff, and data managers could be an implementation strategy to alleviate the oncologist's workload.41 Collaboration with hospital management and health insurers is crucial for resource allocation. Demonstrating results and cost-effectiveness of LTFU care can support resource allocation at institutional and national levels.

Another main study result is the need to enhance knowledge and collaboration with GPs and HCPs from various disciplines and healthcare facilities. This can facilitate effective exchange of medical information between HCPs, appropriate CCSs referrals, and the establishment of suitable care pathways to address CCSs' physical and psychosocial needs. The importance of improving knowledge, communication and collaboration aligns with previous literature,33, 34, 40, 41 which primarily focused on LTFU shared-care models. Professional education for HCPs, including GPs, could be an implementation strategy to improve competence in LTFU care.34, 44 Our study suggests that survivors might lack trust in GPs and local healthcare facilities regarding LTFU care, potentially lowering compliance. HCP education has the potential to increase survivor's confidence in HCPs and GPs competencies as well.44

The present study highlights a gap in detecting psychosocial issues among CCSs at the LTFU clinic and the absence of an adequate follow-up care pathway to manage these issues. It is essential to address this barrier as psychosocial issues are commonly experienced by survivors.15, 45, 46 The importance of addressing CCSs psychosocial needs is underlined by the Institute of Medicine.47 It is crucial to improve access to and collaboration with psychologists, and social workers along with the establishment of a referral structure for psychosocial care.

Our study also showed that some survivors may face limitations in participating in the PCFU Care intervention due to physical, mental, financial, and logistical challenges. Therefore, as an implementation strategy providing guidance, such as aiding survivors with completing the survivor questionnaire, could be considered. Additionally, financial reimbursements as implementation strategies can aid survivors who face financial difficulties or who must cover travel and accommodation costs. However, dedicated funding to address the cost and travel burden for survivors remains a challenge.41 Online consultations and interventions may be a viable alternative for survivors who cannot easily visit the LTFU clinic.

Prior reviews on implementing LTFU care for cancer survivors have predominantly examined GP-led LTFU care models, shared care models between GP and cancer specialists and oncology nurse-led LTFU care models, with a focus on adult-onset cancers.33, 34 The strength of our study is that it concentrates on establishing LTFU clinics as care model for the heterogenous CCS population. LTFU clinics have the capability to manage CCSs who require complex care due to elevated risks of serious late effects.25, 26, 48 Another strength of this study lies in its incorporation of insights from diverse European healthcare systems, providing practical and detailed information on important barriers to address and facilitators to use for successful implementation efforts. This diverse overview of barriers and facilitators based on real-world settings is relevant for other hospitals willing to implement LTFU care for CCSs. Findings can be integrated in implementation strategies to enhance the provision of LTFU care for CCSs in Europe.

A limitation is that this study only considers the HCPs perspective. To design a comprehensive implementation strategy, future research should include perspectives from CCSs and their informal caregivers, hospital management, and policy makers. Another limitation is that data saturation may not have been fully reached in the four focus groups. Determining data saturation becomes more challenging when utilizing focus groups. Some barriers and facilitators were saturated across all four focus groups while other factors were more specific to particular clinic sites. These contextual variations should be taken into account when designing a fitted implementation strategy for LTFU care. However, this study aimed to explore barriers and facilitators proposed by a varied group of HCPs from different European healthcare systems, with the purpose of gathering a diverse overview of barriers and facilitators. This study included 30 participants, among whom the most important HCPs involved in LTFU from the four European clinics that are part of the PCFU study. This exploratory design has the advantage of being relatively fast, inexpensive and can be replicated by other centers to identify barriers and facilitators specific to their healthcare setting with minimal resources.

When interpreting results, cultural differences may affect expressed content and openness in focus groups. Additionally, two centers used their native language during the focus groups and the other two used the English language, which could have influenced the level of participation. However, centers could choose their preferred language, assuming English proficiency when opting for English. In Italy, the HCPs preferred to conduct the focus group in Italian, which was then translated into English one-way. Unfortunately, there's a potential risk of losing meaning by not translating the English version back into Italian.

5 CONCLUSION

This study identified expected barriers and facilitators from the HCPs' perspective for successful implementation of high-quality LTFU care for CCSs using the PCFU Care intervention. Our findings showed that specific attention should be given to knowledge, capacity, and financial issues, along with addressing psychosocial issues of survivors. The results support clinical staff in providing optimal LTFU care and offer practical guidance for integrating the PCFU Care intervention.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dionne Breij: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); writing – original draft (lead). Lars Hjorth: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Eline Bouwman: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); methodology (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Iris Walraven: Supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead). Tomas Kepak: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Katerina Kepakova: Project administration (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Riccardo Haupt: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Monica Muraca: Funding acquisition (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Irene Göttgens: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Iridi Stollman: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (lead); writing – review and editing (supporting). Jeanette Falck Winther: Funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Anita Kienesberger: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Hannah Gsell: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Gisela Michel: Writing – review and editing (equal). Nicole Blijlevens: Supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Saskia M. F. Pluijm: Funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Katharina Roser: Writing – review and editing (equal). Roderick Skinner: Funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Marleen Renard: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Anne Uyttebroeck: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Cecilia Follin: Project administration (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (supporting). Helena J. H. van der Pal: Funding acquisition (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Leontien C. M. Kremer: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (lead); methodology (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Jaqueline Loonen: Conceptualization (lead); funding acquisition (lead); methodology (equal); supervision (lead); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (lead). Rosella Hermens: Conceptualization (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (equal); methodology (lead); project administration (supporting); supervision (lead); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (lead).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“The PanCareFollowUp Consortium, established in 2018, is a unique multidisciplinary European collaboration between 14 project partners from 10 European countries, including survivors (https://pancarefollowup.eu). The aim of the consortium is to improve the quality of life for survivors of childhood, adolescent and young adult (CAYA) cancer by bringing evidence-based, person-centered care to clinical practice. The PanCareFollowUp Consortium has developed two interventions; (1) a person-centered and guideline-based model of survivorship care (PanCareFollowUp Care Intervention) and (2) an eHealth lifestyle coaching model (Lifestyle intervention). At the project end, Replication Manuals that contain the instructions and tools required for implementation of the PanCareFollowUp interventions will be freely distributed.”

FUNDING INFORMATION

“The project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 824982. The material presented and views expressed here are the responsibility of the author(s) only. The EU Commission takes no responsibility for any use made of the information set out.”

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study adhered to local (METC) procedures of the participating centers. The full names of the ethics committees were: Ethische Commissie Onderzoek UZ/KU Leuven (S63072). Facultni nemocnice u sv. Anny v Brno, Eticka komise (41 V/2019). According to national legislation and confirmed by the Health directors of the participating institutes, no ethical approval was needed in Lund and Italy.

CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

Permission via Rightslink Elsevier to reuse a figure that is previously published in The European Journal of Cancer: van Kalsbeek RJ, Mulder RL, Haupt R, Muraca M, Hjorth L, Follin C, et al. The PanCareFollowUp Care Intervention: A European harmonized approach to person-centred guideline-based survivorship care after childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2022;162:34–44 Figure 1. The PanCareFollowUp Care Intervention steps: previsit preparation, clinic visit, and follow-up call.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The PanCareFollowUp project aims to comply with all the four FAIR principles and to share individual de-identified data upon request.