Quality of integrated female oncofertility care is suboptimal: A patient-reported measurement

S. E. J. Kaal and T. N. Schuurman contributed equally and are regarded as two joint second authors.

Abstract

Background

Clinical practice guidelines recommend to inform female cancer patients about their infertility risks due to cancer treatment. Unfortunately, it seems that guideline adherence is suboptimal. In order to improve quality of integrated female oncofertility care, a systematic assessment of current practice is necessary.

Methods

A multicenter cross-sectional survey study in which a set of systematically developed quality indicators was processed, was conducted among female cancer patients (diagnosed in 2016/2017). These indicators represented all domains in oncofertility care; risk communication, referral, counseling, and decision-making. Indicator scores were calculated, and determinants were assessed by multilevel multivariate analyses.

Results

One hundred twenty-one out of 344 female cancer patients participated. Eight out of 11 indicators scored below 90% adherence. Of all patients, 72.7% was informed about their infertility, 51.2% was offered a referral, with 18.8% all aspects were discussed in counseling, and 35.5% received written and/or digital information. Patient's age, strength of wish to conceive, time before cancer treatment, and type of healthcare provider significantly influenced the scores of three indicators.

Conclusions

Current quality of female oncofertility care is far from optimal. Therefore, improvement is needed. To achieve this, improvement strategies that are tailored to the identified determinants and to guideline-specific barriers should be developed.

1 INTRODUCTION

The potential loss of fertility due to gonadotoxic cancer treatments is one of the most important concerns in female adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients.1-3 Therefore, they are interested in receiving information about infertility risks and fertility preservation (FP) options.4-6 Current clinical guidelines recommend oncological healthcare professionals to provide information on infertility risks and FP options, and, if desired, to offer a referral to and counseling by a fertility specialist.7-9 Providing information to female AYA cancer patients affects quality of life positively, reduces long-term regret, and reduces concerns regarding fertility.1, 10, 11 Despite these guidelines and positive effects, studies have shown that the proportion of patients provided with information on their infertility risks and FP options is suboptimal and varies greatly from 26% to 95%.12-17 The referral process to a fertility specialist also shows variation in practice; only 9.8% to 67% is referred.13, 15, 16, 18

These low rates indicate a suboptimal adherence to female oncofertility guidelines and suggest a suboptimal quality of care. In order to improve quality of integrated female oncofertility care, a systematic assessment of current practice is necessary, just as an assessment of determinants that influence guideline adherence.19 Regarding the systematic assessment of current practice, most studies did not assess the quality of care systematically. They reported the number of FP discussions and referrals based on self-reported practices by healthcare providers or medical record documentation. Both methods have limitations. Regarding self-report, healthcare providers might overestimate their performance, and thus, a self-report bias should be taken into account.20 Regarding medical record documentation, disparity between discussions and documentation exists, varying from 4% to 23%.21, 22 Therefore, it would be better to measure quality of integrated care by consulting actual female cancer patients, because it is more important to know what patients remember than what is documented in incomplete medical records. Furthermore, studies have shown that patients can accurately report on their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and characteristics.22, 23

To systematically assess the current quality of female oncofertility care, quality indicators (QIs) can be used. QIs are measurable elements of practice performance for which there is evidence or consensus that it can be used to assess quality, and hence change the quality of care provided.24 In our previous study, key recommendations for high-quality integrated female oncofertility care were selected by means of a Delphi procedure with a multidisciplinary national expert panel.25 After translating these key recommendations into QIs, these are well suited to systematically assess the quality of integrated oncofertility care. Regarding determinants that influence guideline adherence, these can be found on patient, professional and hospital level. Insight into these determinants can explain the variation in care and should be taken into account when developing tailored improvement strategies to improve quality of care, since quality of care does not improve by itself.

In our current study, the first aim was therefore to systematically assess the quality of integrated female oncofertility care by a patient-reported measurement of QIs. The second aim was to measure which determinants were associated with this quality of care to be able to develop tailored improvement strategies to improve quality of integrated female oncofertility care.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design and setting

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted by means of a survey to female AYA cancer patients in six hospitals: three academic hospitals and three (large) non-academic hospitals. In the Netherlands, patients receive multidisciplinary oncological care and can be referred for FP counseling by any medical specialist involved. FP counseling is performed by reproductive gynecologists. In the Netherlands, patients have no financial reasons to refrain from FP counseling or undergoing FP treatment, because it is covered by basic health insurance or by the hospital cryobanks themselves. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (NL61570.091.17) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Study population

Female AYA cancer patients (18 up to and including 40 years) who were diagnosed in 2016 or 2017 and received a (potential) gonadotoxic treatment were eligible to participate. The Netherlands Cancer Registry was used by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) to identify potentially eligible patients in each participating hospital. After identification, the patient's primary oncological healthcare provider was asked to assess the following exclusion criteria: Patient was deceased, severely diseased, had severe psychological problems, had undergone a hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy prior to the start of her cancer treatment, did not receive follow-up care in the participating hospital, or did not understand the Dutch language.

2.3 Survey development

The survey was developed within our research team. The survey consisted of baseline and clinical characteristics (patient's age, partner relationship, diagnosis and cancer treatment, strength of wish to conceive) and questions that represented the QIs (see below). After reaching consensus with the research team, the survey was pilot-tested in five female cancer survivors and four non-cancer patients after which small adjustments were made.

2.4 Quality indicators

In our previous research, we used a systematic Delphi procedure to select key recommendations for high-quality integrated female oncofertility care with a multidisciplinary oncofertility expert panel including female cancer survivors.25 These key recommendations were first extracted from high-quality international clinical guidelines on this subject and then selected and approved by the expert panel by means of three consensus rounds.25, 26 This resulted in 11 key recommendations. Subsequently, the research team transcribed the key recommendations into 11 QIs (defining numerators and denominators). An example of the transcription from key recommendation to a QI is shown in Figure 1. The questions that were developed to measure this QI were as follows: “Did your oncological healthcare provider discuss the risk of infertility due to the cancer treatment with you?” and “When did the oncological caregiver discuss the risk of infertility with you?”. A total of 40 questions were developed to measure the 11 indicators. The questions measured quality of female oncofertility care for female AYA cancer patients focusing on risk communication, referral, counseling, and decision-making. All QIs are shown in Table 1.

| Domain | Quality indicators |

|---|---|

|

Risk communication QI1 QI2 QI3 |

Percentage of patients in an oncological process who receive a gonadotoxic treatment… |

| With whom at least the risk of infertility is discussed by their oncological healthcare provider early in the oncological process (i.e., within 2 weeks). | |

| With whom the consequences (of the treatment) for their fertility are discussed when they have a wish to conceive, and when their ovaries, uterus, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland (or all) are in the irradiation area (pelvic, skull, craniospinal irradiation, or total body irradiation). | |

| Of whom the oncological healthcare provider consulted an expert colleague when he/she had insufficient knowledge about fertility preservation. | |

| Referral QI4 | Percentage of patients in an oncological process who receive a gonadotoxic treatment to whom the opportunity of counseling with a gynecologist with expertise in fertility preservation is offered. |

| Counseling | Percentage of patients in an oncological process who receive a gonadotoxic treatment… |

| QI5 | For whom an individualized selection and risk analysis has been executed within an expert multidisciplinary team (i.e., primary oncological healthcare provider and treating gynecologist). |

| QI6 | (Who are estimated as medically fit for the procedure, are expected to be able to tolerate the treatment regimen, have sufficient time before the commencement of their cancer treatment, and are informed of the potential risks of hormonal treatment including the risks of cancer progression), with whom oocyte and embryo cryopreservation has been discussed during fertility preservation counseling. |

| QI7 | To whom embryo cryopreservation is offered as an effective and safe method, when time and circumstances allow for it. |

| QI8 |

Who have had fertility preservation counseling with a gynecologist in which all aspects (a – h) have been discussed. a. The chance to preserve ovarian, uterine function, or both, and the chance of spontaneous pregnancy after cancer treatment. b. The chance to preserve ovarian, uterine function, or both, and the chance of pregnancy when using different fertility preservation methods, and expectations for the future. c. The risks of fertility preservation procedures: delay of cancer treatment, surgery (laparoscopy, laparotomy), risk of reintroducing the tumor (metastases) after autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue, premature menopause after cancer treatment and unilateral and partial oophorectomy. d. The conditions to undergo fertility treatment after cancer treatment, (number of years a patient should be relapse-free after curation, posthumous reproduction, etc.). The contracts should also be discussed. e. Alternatives, such as oocyte donation, gestational surrogacy, or adoption. f. Necessary tests before a fertility preservation treatment, such as standard screening for viral pathogens and sexually transmitted diseases. g. Hormonal screening through blood testing. h. Possibilities to treat endocrine consequences owing to the loss of ovarian function. |

| QI9 | Who have been well-informed about all aspects of the treatment prior to performing emergency IVF. |

|

Decision-making QI10 QI11 |

Percentage of patients in an oncological process who receive a gonadotoxic treatment… |

| With whom a shared decision has been made concerning protecting future fertility (together with oncological healthcare provider and gynecologist) | |

| Who have had fertility preservation counseling which was supported with written, digital information, or both. |

2.5 Data collection

Eligible patients received an invitation letter from their primary oncological healthcare provider to participate. After obtaining informed consent, a paper version of the survey was sent by mail in 2020/2021. In total, 344 patients were invited to participate. If no informed consent or completed survey was received within 3 weeks, one reminder was sent.

2.6 Data analysis

QI adherence scores were calculated per indicator. Herewith, current practice was expressed as the percentage of patients who received care as recommended in the QI. In addition, hospital variation was calculated.

To evaluate which determinants were associated with the quality of integrated female oncofertility care, we first studied the univariate relation between indicator scores (dependent variables) and determinants (independent variables) that could influence the indicator score. Determinants were extracted from literature and included age, relationship status, parity, strength of wish to conceive, type of cancer, type of cancer treatment, time before start of cancer treatment, type of healthcare provider, and type of hospital.12, 15, 16, 18, 27, 28 We used a generalized linear mixed model which accounts for the nested structure of data, because individual patients (patient level = 1) are nested within hospitals (hospital level = 2). For determinants with p < 0.20 in univariate analyses, we performed multivariate logistic regression. Collinearity between determinants was also tested. If a correlation (>0.6) was detected, the most relevant variable with respect to content was included in the multivariate analyses. Odds ratios described the association between indicator scores and determinants. Indicator scores were recalculated for each indicator and for each part of the associated determinant. For example, an indicator could be recalculated for all patients aged 18–29 years and for all patients aged 30–41 years.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study population

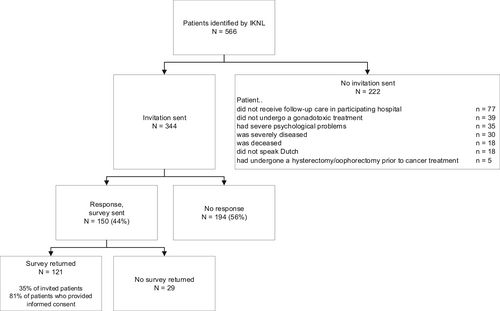

In total, 566 patients were identified by IKNL of whom 344 met the inclusion criteria. Figure 2 shows reasons for exclusion. A total of 121 out of 344 (35%) surveys were returned. Mean patient age at diagnosis was 34 years, 60.3% was diagnosed with breast cancer, and 37.2% had undergone FP treatment (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

|

Response rate total and per hospital Academic hospital

Large non-academic hospital

|

121/344

|

35 42.9 27.3 34 42.3 33.3 37 |

| Mean age at diagnosis | 34.0 years (range 18–41, SD 5.1) | |

Type of cancer

|

|

0.8 1.7 60.3 11.6 4.1 0.8 2.5 0.8 12.4 1.7 1.7 1.7 |

Cancer treatment

|

|

59.5 92.6 37.2 16.5 66.1 70 10 12.5 7.5 9.1 |

Relationship status

|

|

74.4 16.5 9.1 |

Parity

|

|

41.3 58.7 40.8 40.8 17 1.4 |

Strength of wish to conceive at diagnosis (mean, scale 1–10)

|

5.8 (range 1–10, SD 3.5, median 5) 7.0 (range 1–10, SD 2.9, median 7.5) 4.9 (range 1–10, SD 3.6, median 5) |

|

Number of patients who had undergone fertility preservation treatment (3 patients had 2 treatments)

|

45/121

|

37.2 53.3 24.4 6.7 20 2.2 |

3.2 Current quality of female oncofertility care and variation

Guideline adherence, measured with the 11 QIs, is presented in Table 3. Overall, 8 out of 11 QIs scored below 90% adherence. Regarding the different domains, for the domain risk communication a score of 72.7% was reported for “discussing the risk of infertility within 2 weeks after diagnosis” (QI1). The indicator with the lowest score in this domain was “consulting an expert colleague when an oncological healthcare provider has insufficient knowledge” (QI3, 43.8%); the indicator with the highest score was “to discuss infertility risks when a patient receives gonadotoxic radiation therapy” (QI2, 95.8%). In the referral domain, the indicator “offering FP counseling with a gynecologist to a patient” scored 51.2% (QI4). Indicators in the counseling domain showed a range from 18.8 to 100%, with “discussing all aspects in FP counseling” (QI9) as lowest score, and “discussing oocyte and embryo cryopreservation with eligible patients” (QI6) as highest score. In the domain of decision-making, a score of 73.3% was reported for “making a shared decision” (QI10) and a score of 35.5% for “supporting the decision with written and/or digital information” (QI11).

| Quality indicator | Total score Nominator/denominator | % | Variation per hospital % | Missing data % | Determinants (in multivariate analyses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

QI1—Risk of infertility discussed within 2 weeks after diagnosis

|

88/121 29 35 24 27 6 |

72.7 | 46.7–83.3 | 0 | None |

| QI2—Risk of infertility discussed when pelvic, skull, craniospinal, or total body irradiation takes place | 23/24 | 95.8 | 85.7–100 | 0 | None |

QI3—Oncological healthcare provider consulted expert colleague when he/she had insufficient knowledge about fertility preservation

|

7/16 22/120 7/16 |

43.8 | 25–100 | 27.3 | None |

| QI4—Opportunity of counseling with a gynecologist is offered | 62/121 | 51.2 | 40–70.8 | 0 |

Patient's age; Strength of wish to conceive |

QI5—Individualized selection and risk analysis has been executed within an expert multidisciplinary team prior to fertility preservation treatment

|

19/21 28/35 19/21 |

90.5 | 0–100 | 53.3 | None |

QI6—Oocyte and embryo cryopreservation has been discussed with eligible patients

|

22/22 33/36 36/38 37/39 22/22 |

100 | 100 | 47.5 | None |

| QI7—Embryo cryopreservation is offered as an effective and safe method, when time and circumstances allow for it | 34/39 | 87.2 | 75–100 | 2.6 | None |

QI8—All aspects (a – h) have been discussed in fertility preservation counseling

|

6/32 28/37 20/31 7/26 16/34 14/41 27/37 6/32 12/37 |

18.8 | 0–40 | 47.5 | None |

| QI9—Well-informed about all aspects of the treatment prior to performing emergency IVF | 27/33 | 81.8 | 60–100 | 5.7 | None |

| QI10—Shared decision has been made concerning protecting future fertility | 44/60 | 73.3 | 42.9–100 | 0 | Type of health care provider |

| QI11—Decision was supported with written and/or digital information | 43/121 | 35.5 | 6.7–50 | 0 |

Strength of wish to conceive; Time before start of cancer treatment |

In all four domains, QI scores varied greatly among the six participating hospitals (Table 3). In 10 out of 11 QIs >20% variation was observed among hospitals.

3.3 Determinants

Results from univariate analyses are shown in Table S1; for determinants with p < 0.20, multivariate analyses were performed. Multivariate analyses showed that 3 determinants at patient level (patient's age, strength of wish to conceive, and time before start of cancer treatment) and 1 determinant at professional level (type of healthcare provider) influenced the scores of 3 indicators significantly (Table 4). Patients who were younger (<30 years), or with a higher wish to conceive (score 6–10) showed a greater adherence to the indicator “offering FP counseling with a gynecologist” (QI4). Treatment by a medical oncologist was associated with a lower score for “making a shared decision” (QI10), and patients with a higher wish to conceive or with more time before start of cancer treatment (>2 weeks) showed a higher score for “receiving written and/or digital information” (QI11).

| Quality indicator | Determinants | N | Multivariate analysis Odds ratio (95% CI), p-value | Stratified indicator score % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QI4—Opportunity of counseling with a gynecologist is offered |

Patient's age

Strength of wish to conceive

|

24 97 61 60 |

4.03 (1.34–12.23), p0.015 Ref Ref 3.18 (1.46–6.95), p0.004 |

79.2% 44.3% 36.1% 66.7% |

| QI10—Shared decision has been made concerning protecting future fertility | Type of healthcare provider

|

21 39 |

Ref 5.22 (1.29–21.12), p0.02 |

52.4% 84.6% |

| QI11—Decision was supported with written and/or digital information |

Strength of wish to conceive

Time before start cancer treatment

|

61 60 29 92 |

Ref 2.69 (1.20–6.05), p0.02 Ref 3.03 (1.07–8.62) p0.04 |

26.2% 45% 20.7% 40.2% |

4 DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the quality of integrated female oncofertility care measured by a patient-reported measurement with a set of systematically developed QIs is far from optimal. Improvement potential (indicators with <90% adherence) was found for 8 out of the 11 QIs representing all domains in female oncofertility care: risk communication, referral, counseling, and decision-making. In addition, a great variation in indicator scores (>20% for 10 out of 11 QIs) was seen among hospitals. Four determinants (patient's age, strength of wish to conceive, time before cancer treatment, and type of healthcare provider) were found to significantly influence the scores of three indicators on referral and (support of) shared decision-making.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which the quality of integrated female oncofertility care was systematically assessed with a set of QIs, using a patient-reported measurement. In a previous study conducted in the Netherlands, oncological healthcare providers were asked via a survey how often they discuss fertility issues with female cancer patients and refer them for FP counseling. In total, 79% usually or always discussed fertility issues, and 54% usually or always referred patients for FP counseling.15 These percentages are in line with our indicator scores on these items (QI1 72.7% and QI4 51.2%) meaning that still no improvement in quality of care has taken place.

Comparing with patient survey studies in other countries without a systematic assessment, our indicator scores are lower. An Australian study reported a discussion rate about infertility risks of 88%, and referral rate of 59%,12 and an American survey study found a discussion rate of 74.5%.29 This could be explained by the study population; in those studies, patients were much younger (15 and 21 years, respectively), which was a determinant we found to increase referral rates.

Furthermore, in contrast to our study, these previous studies focused on one or two elements of female oncofertility care, for example on receiving information, receiving fertility preservation counseling, or having fertility preservation treatment. We focused on all domains in female oncofertility care, particularly on information provision, on offering referral for counseling, on counseling by a gynecologist, and on fertility preservation decision-making. All these domains have shown to be important in delivering high-quality integrated female oncofertility care as these were selected as key elements by a multidisciplinary expert panel and based on international evidence-based guidelines.25 In addition, patients want to be fully informed about all aspects of fertility preservation and supported in their decision.4, 30, 31 Unfortunately, we found low scores for the indicators that cover these items; about one fifth for discussing all aspects in FP counseling, one third for supporting the decision with written and/or digital information, and three quarters who have made a shared decision regarding FP. This underlines the fact that not only discussion and referral rates need improvement, but also FP counseling and FP decision-making. A way to improve FP counseling and decision-making could be the provision of a decision aid.32, 33 We developed a FP decision aid that is tailored to cancer type and associated cancer treatments.34 First results are promising, but future research should evaluate its effectiveness.

We found that a higher patient's age was associated with lower referral rates. This is in line with previous studies.35-37 This might be explained by the fact that healthcare providers think that patients who are older do not have a wish to conceive anymore, without asking for it. Furthermore, we found that a higher wish to conceive was associated with higher referral rates and receiving written and/or digital information. A possible explanation is that these patients might ask themselves for a referral. Both associations underline the importance of asking a patient for her needs and wishes regarding future fertility. Our determinants could be used to develop tailored improvement strategies to improve quality of integrated female oncofertility care. For example, oncology nurses can play an essential role in this, as they already play an important role in cancer care programs, and as patient advocates.38-40

A strength of our study is that it is the first study that systematically assessed the quality of integrated female oncofertility care using QIs extracted from high-quality international clinical guidelines and using a patient-reported measurement. Furthermore, we included a diverse study population, that is, female cancer survivors with all types of cancers and treatments, from all types of hospitals, of all reproductive ages, with and without children or relationship, and with a variety in their strength of wish to conceive. This ensured that our results represent clinical practice and are generalizable to other countries.

However, despite the systematic assessment, some limitations should be considered in the interpretation of our results. Selection bias could have occurred because of our low response rate, although this is in line with other survey studies among AYA patients,41 and because each primary oncological healthcare provider had to give consent to invite a patient for participation. In case of exclusion, the reason for exclusion was shared, however, this could not be checked by the research team because of regulations regarding data protection. This could have led to exclusion of patients that did not adhere to QIs, while they did match the inclusion criteria which would mean the quality of care was even lower. We have tried to minimize this selection bias by explicitly asking each healthcare provider to stick to the in- and exclusion criteria, and in doubt, to discuss the case with the research team. In addition, bias could have occurred because of selective response by patients. For example, dissatisfied patients might be more likely to complete the survey leading to an underestimation of quality of care. However, in comparison with other studies, we found a high rate of patients who had FP treatment (37%).11, 42 This may indicate that patients who have received fertility preservation care as recommended were more likely to participate than patients who did not receive recommended care. This might have led to an overestimation of the quality of integrated female oncofertility care, and in fact, the quality was even lower. Furthermore, recall bias could have played a role because patients might have a poor recall on discussions about fertility issues when they are confronted with a cancer diagnosis and because they were asked to fill in questions three to 4 years after their diagnosis, treatment, and consultation. However, it is also known from other qualitative studies among cancer survivors that fertility issues are almost as important as the devastating cancer diagnosis for many patients.3, 43 This was confirmed in our study, as for the “basic” questions about fertility discussions (QI1, 2, 4, 10, 11) there were no missing data. Regarding the questions that asked for very specific details of information given in consultations (QI6 and 8), or that asked for things a patient might not know (QI3 and 5) relatively many data were missing. So, in future it should be evaluated if these QIs could be measured in medical records or provided by healthcare providers to minimize this bias. Last, it might be interesting to compare the survey results to what is documented in the medical record to check for the disparity between what patients remember from the discussion and the documentation.

In conclusion, our study showed a considerable difference between daily practice performance and care as described in evidence-based guidelines. Low guideline adherence is associated with lower, and therefore suboptimal, quality of care since guidelines assist in delivering the most optimal care. Suboptimal care increases concerns regarding fertility and long-term regret, affecting female cancer AYA patients' quality of life negatively.2, 10, 11 Therefore, improvement is needed. To achieve this, improvement strategies that are tailored to the identified determinants and to guideline-specific barriers should be developed, for example a decision aid.34, 44, 45 Our QI set could then be used to evaluate whether the improvement strategy has a positive effect on quality of integrated female oncofertility care in both the Netherlands and internationally.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MvdB, DDMB, CCMB, and RPMGH involved in study concept and design. MvdB, CCMB, SEJK, TNS, CMPWM, JT, JMT, and MJDLvdV involved in data acquisition. MvdB, DDMB, CCMB, and RPMGH involved in data analysis and interpretation. MvdB involved in writing original draft. All authors involved in reviewing the article and final approval of article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all patients and all their primary oncological healthcare providers for participating in our research. Furthermore, we would like to thank ir. R.P. Akkermans for his help in analyzing all data.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was funded by the Paul Speth Fund and the Radboud Oncology Fund.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (NL61570.091.17) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent to participate was obtained for all participants.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Study data are available upon request.