Music therapy for depression: A narrative review

Abstract

As living standards improve, mental and physical health have been gaining increasing attention. Presently, depression is one of the most severe mental health issues. Depression affects the quality of life of affected individuals because it lasts for a very long time and is generally difficult to cure. Currently, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are the two main approaches for treating depression. However, some principles and characteristics of pharmacotherapy remain unclear, and its side effects are significant and noticeable. In addition, ordinary psychotherapy requires the assistance of a qualified psychotherapist, which is usually hard to find and expensive. Both methods are burdensome to the patients, making it difficult for them to benefit. As an easy-to-obtain therapy, music therapy has been recommended by physicians as an auxiliary therapy for various diseases to regulate patients' emotions and help the primary treatment methods to obtain better therapeutic effects. This review investigates and summarizes recent articles on the pathogenesis of depression and the effects of music therapy on depression. Its results show that music therapy is effective and available. However, a systematic treatment plan has not yet been formulated due to the lack of samples and short follow-up times. Future studies should include more samples and follow-up patients after the treatment period to address the continuous effect and principle of music therapy.

Key points

What is already known about this topic?

-

The number of individuals suffering from depression, which can eventually lead to suicide, is increasing, and knowledge about depression remains limited. Individuals' perceptions of depression are biased, and it is crucial to raise awareness of depression.

What does this study add?

-

This review summarizes and classifies recent findings on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment methods of depression. It introduces the principles and practice of musical interventions for depression with various etiologies. In particular, it highlights the recent progress of depression research and the prospects of music therapy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Depression (also known as major depressive disorder [MDD]) is a debilitating disorder with typical symptoms of low enthusiasm and loss of interest. Chronic depression may lead to cognitive impairment and autonomic symptoms such as insomnia and inappetence. Depression is twice as likely to develop in women as in men and affects one in six adults.1, 2 Decades of scientific research and advances in neurobiology have increased the understanding of depression. Nonetheless, many unknowns about the disease remain. Presently, many studies have explored biomarkers for diagnosing depression, but their results are not encouraging, and its diagnosis still relies mainly on experienced psychiatrists. Two programs are accepted to treat depression: pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Different manuals agree that patients with moderate-to-severe depression should be treated with pharmacological interventions or a combination of pharmacological and psychological interventions. In contrast, those with mild depressive episodes can initially be treated with psychotherapy alone.3-5

Music can positively affect pain relief, sleep disorders, and other aspects. The Australian Society of Music Therapy defines music therapy as “the creative and systematic use of music to maintain health and vitality.”6 Similarly, in 1999, the American Association for Music Therapy defined it as “the use of music in order to achieve the goals of therapy, that is, to improve, maintain, and promote the health of the mind and body”.6 While antidepressants are commonly used to relieve depressive symptoms, they often lead to adverse drug dependence and unnecessary side effects. In particular, mothers with postpartum depression are not given antidepressants to protect their infants from them. Psychotherapy often requires the intervention of an experienced psychotherapist over several sessions, which is often expensive and unaffordable for most families. As an alternative, music therapy has no apparent side effects or adverse reactions. It is a well-tolerated, non-invasive, and inexpensive treatment requiring very little time and effort.7

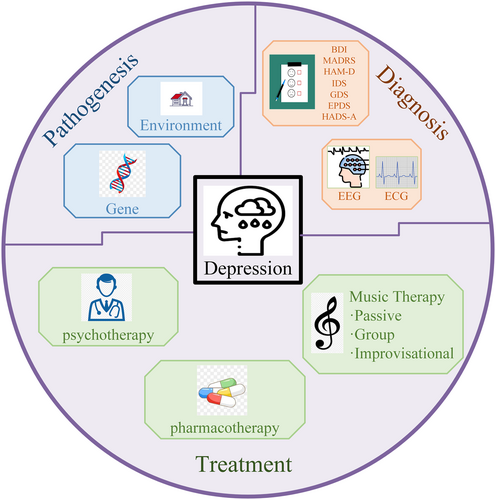

This review investigates the neurobiological principles, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of depression over the past 20 years, as depicted in Figure 1. It focuses on the principles and trials of music therapy for patients with depression.

Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of depression.

2 PATHOGENESIS OF DEPRESSION

Various factors can contribute to depression, with genetic factors contributing approximately 35%, while environmental factors, such as childhood abuse, are closely related to the risk of developing depression. Although advances in neurobiology have increased our understanding of the pathophysiology of depression, its exact causes are diverse and uncertain. Researchers have sought to explore the determinants of depression by studying neurobiological changes in patients with depression.

Patients with depression were found to have smaller hippocampal volumes than those without depression, and they had altered activation or connectivity of brain neural networks.5 Some disruption was found in major neurobiological stress response systems in patients with depression.5 Gene expression in patients with depression is also a topic of scientific interest. Currently, altered expression patterns have been identified for various genes, such as those associated with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammation.8 However, since most available research often uses laboratory-specific assays and data analysis based on relative quantification, no findings have yet been translated into clinical practice.9

3 DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF DEPRESSION

3.1 Diagnosis of depression

The characteristics of depression are (I) at least one discontinuous depressive episode lasting at least 2 weeks and (II) depressed mood, decreased interest, insomnia, inappetence, and impaired cognitive function.5 Since these symptoms also often occur in patients with other psychiatric or non-psychiatric disorders, diagnosing depression has been challenging. However, prompt diagnosis and treatment are critical for patients since they determine whether depression can be intervened at an early stage.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association published the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),10 and the application of exclusion criteria has made diagnosing MDD possible.5 Currently, MDD is diagnosed based on behavioral observations, patient-reported symptoms, various scales, and DSM-5 criteria. For decades, researchers have explored molecular or imaging biomarkers for assessing clinical depression. While some physiological features have been identified, none are currently widely accepted.11

3.1.1 Subjective diagnostic methods

Beck depression inventory (BDI)

The BDI is a self-report scale developed by A. T. Beck. It can effectively measure current depressive status in both adolescents and adults.12 Beck recorded the symptoms his patients verbally reported and then classified their medical records according to intensity or severity. Valid symptoms distilled from his cases were used to design the initial BDI version. There are three versions of the BDI: the original (BDI),13 the first revision (BDI-i/-1A),14 and the second revision (BDI-II).15 Depression is diagnosed and monitored based on the total BDI score: 0–13 indicates no depressive symptoms, 14–19 indicates mild depression, 20–28 indicates moderate depression, and 29–63 indicates severe depression.

Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS)

Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) is a reliable 10-item scale that measures depression symptoms, including sadness, stress, sleep disorders, changes in appetite, a lack of pleasure, pessimism, and suicidal thoughts. Patients self-evaluate based on symptoms observed over the past week. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale: from 0 (asymptomatic) to 6 (severe). The total MADRS score ranges from 0 to 6016: 0–7 indicates no depression, 8–15 indicates recovery, 16–25 indicates mild depression, 26–31 indicates moderate depression, 32–44 indicates severe depression, and ≥45 indicates very severe depression.17

Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D)

The HAM-D (also abbreviated to HRSD and HDRS) was created to assess the severity of depression in adult patients. The original version18 comprised 17 items, but later revisions added four items.19-22 The total HAM-D score ranged from 0 to 54: 0–6 indicates no depression, 7–17 indicates mild depression, 18–24 indicates moderate depression, and ≥25 indicates severe depression.

Inventory of depressive symptomatology (IDS)

IDS is an effective method for assessing the severity of depressive symptoms,23 which can be assessed using IDS scores. There are two forms of the IDS: IDS-C is an observational version for physicians, and IDS-SR is for patients to assess themselves. The IDS comprises 30 items scored on a four-point Likert scale. The total IDS score ranges from 0 to 84: 0–13 indicates no depression, 14–21 indicates mild depression, 22–30 indicates moderate depression, 31–38 indicates severe depression, and ≥39 indicates very severe depression.24

The Quick IDS (QIDS SR-16)25 is a self-reported questionnaire comprising 16 items about depressive symptoms. The total QIDS SR-16 score ranged from 0 to 27. The higher the QIDS SR-16 score, the more severe the depression.

Geriatric depression scale (GDS)

The GDS was specifically designed to identify depression in older adults.26 It consists of 30 self-assessed items, answered yes or no, and is commonly used as a routine part of a comprehensive assessment of aging. A GDS score of 11 is the threshold usually used to separate those with (≥11) and without (<11) depression. The GDS has shown good reliability and validity.27

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)

EPDS is used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms in women.28 Originally developed for postpartum women, it measures a woman's mood after delivery and is a useful indicator of those at risk of depression. Ten items are set in EPDS and each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale: from “not at all” (0) to “Yes, most of the time” (3). A cut-off total score of 9/10 is used to screen postnatal depression.28 The EPDS was found to have satisfactory sensitivity and specificity and to be sensitive to changes in depression severity over time. It can be completed quickly without needing professional knowledge.29

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

In the HADS,30 patients self-rate the severity of their anxiety (HADS-A) or depression (HADS-D) symptoms from 0 (not exactly) to 3 (most of the time). This questionnaire is based on 14 items. Seven items are used to rate HASD-A, and the other are used to rate HASD-D. Both scores ranged from 0 to 21 (0–7 = normal, 8–10 = mild, 11–14 = moderate, 15–21 = severe), with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety and/or depression. The HADS-D and HADS-A were found to be reliable tools for detecting depression and anxiety, respectively, in hospital clinics and effective indices to measure the severity of mood disorders.31

3.1.2 Objective diagnostic methods

Diagnosing depression has long been a difficult problem for scholars, physicians, and patients. Theoretically, diagnosing depression is subjective, often intertwined with other diseases or even combined with other diseases, and has similarities in symptoms to other disorders. Leading biological hypotheses suggest that major depressive episodes and relapse can lead to biological changes. Researchers have consistently sought to identify objective biomarkers to diagnose depression. Biomarkers from leading theories include neuroimaging and many chemicals in the human body,32 but their results are unsatisfactory. In May 2021, Google's parent company Alphabet announced the failure of its machine learning plan “Project Amber” after three years of research. This plan was originally an attempt to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to discover depression and anxiety biomarkers. However, ultimately, it failed to identify a single biomarker for depression or anxiety. Its failure may mean that multiple biomarkers must be considered together to diagnose depression. This section summarizes the diagnosis methods for depression proposed in various recent research studies. These results have various limitations and require additional research.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An EEG records the spontaneous biological discharges of the brain. These data can be used to analyze the energy of the different frequency bands, which reflect brain activity. The EEG frequency bands related to depression are shown in Table 1.

| EEG frequency band | Function |

|---|---|

| Alpha | Reflects inactivity and relaxation, asymmetry is related to the approach-withdraw model |

| Beta | Related to the concentration of expectation, anxiety and introversion |

| Theta | Related to emotional processing |

| Gamma | Related to attention, mood swings and sensory systems |

| Delta | Related to deep sleep |

De Aguiar Neto et al. summarized recent studies on the EEG characteristics of depression and concluded that the gamma and theta bands have good diagnostic functions. Other bands may be helpful for diagnosis when classifiers are used.33

Brain connectivity is also a feature of interest to researchers. Liu et al. found that during music perception, patients with severe depression disorder showed reduced connectivity patterns in the delta band and increased connectivity patterns in the beta band. Healthy individuals exhibited left lateralization, whereas patients with depression did not exhibit such a lateralization effect.34

The alpha band is also important in diagnosing depression. The resting EEGs of patients with major depression showed higher power in the high alpha band and lower power in the low alpha band.35 Alpha asymmetry is another commonly studied biomarker, which measures relative alpha-band activity between hemispheres, particularly at frontal lobe electrodes.33

Studies have shown that a decrease in depressive symptoms corresponds to an increase in dorsolateral cortical activity,36 and an inverse correlation was observed between the intensity of the alpha rhythm and cortical activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.37 Alpha asymmetry in the frontal lobe also indicates reduced activity on the left side,38 and patients' EEG results showed a general increase in alpha-band energy.39 Patients with severe depression who did not have suicidal thoughts also had a high index of frontal-lobe alpha-asymmetry.40 In a recent review, left-sided tendencies found in emotion regulation and cognitive processes were also found in patients with depression,41 but the result did not prove an absolute correlation.

In summary, examining the complex associations between brain mechanisms is worthwhile to help identify quantitative biomarkers of depression, and similar research should be encouraged in the future.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

For the past 3 decades, researchers have studied the structural and functional changes in the brains of patients with depression using diagnostic imaging techniques. Changes in brain structure and function are common in patients with depression. A recent review evaluated structural and functional MRI studies on MDD published from 1995 to 2018,11 indicating that the research over the past few decades has yielded a number of results. However, MRI studies of MDD have been stagnant since 2012, and there is an urgent need for new imaging techniques and image analysis programs to advance the field.

Structural MRI can measure the volume of various brain regions, which can be used to detect anatomical changes in the brain. While many studies have found structural changes in brain regions in patients with depression, their findings are not specific to depression. Studies have found enlarged lateral ventricles and an increased volume of cerebrospinal fluid in patients with depression.42 However, similar ventriculomegaly has been found during normal aging43 and in several other psychiatric disorders.44 Reductions in the overall volume of the frontal lobe in the prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices, which were related to age or sex,45 have also been found in the brains of patients with depression. Structural changes have also been found in areas such as the temporal, parietal, and cerebellum,46-49 but these changes were not specific to depression.

Functional MRI is an anatomical imaging modality that measures blood flow and metabolism in specific brain regions. Most functional MRI studies have used blood oxygen level dependence (BOLD) to assess functional brain activity. When brain activity increases, oxygen consumption increases, and the flow of oxygenated blood into the brain leads to an increase in BOLD signals. Researchers have focused on three large-scale brain function networks: default mode, executive control, and salience. The brain regions and functions involved in these three functional brain networks are listed in Table 2. Many studies have found changes in the activity of brain functional networks in patients with depression,50-54 but whether these changes are specific to depression remains unknown.

| Brain functional network | Brain area | Function |

|---|---|---|

| DMN | Midline, inferior parietal | Absent-mindedness, spontaneous thought |

| ECN | Prefrontal, posterior parietal | Cognitive tasks that require attention, such as working memory and task switching |

| SN | Cingulate, frontal, insular | Autonomic and emotional processing |

Despite the increasing number of MRI studies on depression, the existence of the reverse thrust fallacy does not prove that these changes in brain structure or function are specific to depression. Therefore, MRI brain scans can help psychologists determine whether the patient has brain lesions but cannot determine whether depression exists. There remains a long way to go in applying brain MRI to diagnosing and treating clinical depression, and researchers should use advanced technology to further study depression at the biological level. Understanding the root causes of depression not only contributes to understanding the disorder, which can help millions of patients with depression, but can also influence the study of other mental disorders.

3.2 Treatment of depression

There are two commonly accepted programs to treat MDD: psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Psychological intervention can occur at any time. Drug intervention is required in severe cases. Consideration should be given to the patient's medical history, previous treatments, and receptivity to treatment. In addition, in cases of mild depression, it is possible to adopt the initial strategy of “watchful waiting” without treatment. However, if the condition does not improve after 2 weeks, action should be taken immediately.

In the 1950s, the anti-hypertensive drug reserpine was found to reduce levels of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine), norepinephrine, and dopamine, and some patients taking these drugs gradually developed depression.55 Therefore, these neurotransmitters were thought to be associated with depression. Monoamines were initially discovered as antidepressants, but how they work remains incompletely understood. Moreover, antidepressants pose tolerability problems. Their common adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, headache, insomnia, and loss of appetite, while their long-term use leads to weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and sleep disturbances.56

Researchers have attempted to develop fast-acting drugs with few side effects without monoamines for the last 20 years. There are already some preliminary results, including tachykinin precursor 1 (TAC1) antagonists,57 glutamatergic system modulators,58 anti-inflammatory drugs,59, 60 opioid tone modulators and opioid-κ antagonists,61, 62 hippocampal neurogenesis stimulation therapy,63 and glucocorticoid therapy.64 It is hoped that these drugs can treat depression without significant side effects, but how far they will go remains unclear.5

There are many different forms of psychotherapy for depression. The most common are behavior activation therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, mindfulness therapy, problem-solving therapy, and psychodynamic therapy.5 Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown psychotherapy to be effective in treating MDD, but no significant consistency or clinically meaningful differences have been observed between different types of psychotherapy.65-67

With scientific and technological progress, there are many new therapies, including multiple approaches such as repetitive68 and deep69 transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct-current stimulation,70 magnetic epilepsy treatment,71 low-field magnetic stimulation,72 vagus nerve stimulation,73 deep brain stimulation,74 and various pharmacological methods.5 However, the effects of these methods on individuals remain unknown; therefore, they are primarily used to treat resistant depression. New technologies must be further explored.

Music is a common art form and cultural activity that positively affects pain, sleep disorders, and other aspects. The first music therapy society was organized in Michigan in 1944, and a music therapy program was established at Kansas State University in 1946. Presently, music therapy is widely used to treat depression.75

4 EFFECT OF MUSIC ON PATIENTS WITH DEPRESSION

Music can evoke and enhance a wide range of emotional experiences. Patients with depression often fall into negative moods, and their ability to regulate emotions is impaired. However, studies have shown that mood regulation in patients with depression is not entirely ineffective.76 When patients with depression engaged in artistic activities, their overall use of self-reported emotion regulation strategies was significantly lower. Their ability to adaptively regulate their emotions was impaired. However, their rate of using avoidance emotion regulation strategies was the same as that of those without depression. Music can evoke positive emotions in patients and help them detach from negative emotions.

The physiological mechanism of music's effect is complex. No fully developed theoretical framework has yet been proposed to explain its principles completely. Humans perceive sound through the auditory system, which encodes elements such as rhythm, tone, and pitch into neuronal signals. In the central nervous system, these signals integrate with the signals of several other neurons and travel in both directions to the autonomic nervous, endocrine, and immune systems.77 Music has been found to activate serotonin and reduce cortisol, blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR).78 Functional magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging has shown that music awakens the peripheral and central nervous systems via the hypothalamus-brainstem-autonomic nervous system axis.79

The causes of depression are varied, with genetic factors, environmental factors, and even underlying diseases all contributing to the development of depression. Physicians are now studying neurobiological changes in patients with depression to develop treatments that reverse these changes. Music therapy has also been found to reverse neurological changes in the brains of patients with depression. However, how music therapy positively affects depression must still be more thoroughly researched and understood.

Papadakakis et al. found that rats exhibited decreased social function and increased anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in adulthood after early life stress due to maternal separation. These effects were reversed after listening to music as an intervention.80 Jenkins et al. found that nucleus accumbens activation was lower in patients with depression than in healthy controls, supporting the theory that patients with depression cannot maintain the activation of reward networks. It was also found that pleasurable classical music affected key neural reward circuits in patients with depression.81 Using functional near-infrared spectroscopy to monitor prefrontal hemodynamics, Feng et al. found that the effects of music therapy on patients with depression involved the activation of the prefrontal, orbital prefrontal, and ventral prefrontal cortices.82 Fachner et al. recorded resting EEGs from patients with depression before and after music therapy. Examining activity in the frontotemporal region, they found that listening to music altered frontal lobe alpha asymmetry and increased frontal midline theta in patients with depression.83 Feneberg et al. administered a music-listening intervention to patients with somatic disorders and depression. Examining data on somatic symptoms and stress markers, they found that listening to music alleviated somatic symptoms primarily by reducing patients' subjective stress.77

In conclusion, how music acts on patients with depression is complex, involving various aspects of the nervous system, endocrine system, and immune system. However, currently, no framework can completely explain every aspect of how music affects patients with depression. Nonetheless, previous studies have shown that music is beneficial to patients with depression, although music therapy remains to be clinically adopted as an adjunct.

5 PRACTICE OF MUSIC THERAPY FOR DEPRESSION

-

Treatment within the framework of structured therapy.

-

Musical interactions (e.g., music listening, improvisation, and various types of musical expression) occur between the therapist and their patients or team members.

-

The purpose of the treatment is to improve health.

-

Music, relationships, or responses elicited by music are major therapeutic variables.

Based on the above concepts, we searched the published literature for RCTs and quasi-experimental studies that compared a music-related intervention to reduce depression levels to a control intervention. We searched Google Scholar, Science Direct, PubMed, and other databases using various search terms, including “music therapy” and “depression,” with the primary outcome being levels of depressive symptoms.

Not all of the music chosen by the patients can achieve mood regulation. Patients in a depressed mood would choose to listen to music that aligns with their current mood. In this way, their feelings could be acknowledged, giving them a sense of effectiveness, which sometimes reinforces negative emotional states, contrary to the goal of using music to regulate emotions.85 In her 2013 B.Sc. honors thesis, Kendra Bartel surveyed 670 college students and found that their music preferences influenced their depression levels, indicating that music does affect depression.86 In 2021, Sameena et al. found that listening to folk or mixed music positively affected psychological distress symptoms, psychology, and quality of life in patients with gynecological cancer, while new-age music negatively affected these factors.87 These observations highlight why a music therapist must support music therapy.

Table 3 summarizes recent studies on practicing music therapy for depression.

| Reference | Patient population | Experimental methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsu 200488 | Resident patients with MDD (N = 54) | Pretest-posttest with a two-group repeated measures design; intervention group (IG; n = 27): Music and medication; control group (CG; n = 27): Drug. | IG: Significant improvement in various scores; CG: also improved, but not as significantly as in the IG. |

| Castillo-Pérez 201089 | Patients with moderate to low-grade depression (N = 79) | RCT; music therapy group (MTG; n = 41): Music; psychotherapy group (PG; n = 38): Psychotherapy based on CBT. | MTG: 29 improved, four did not, and eight gave up; PG: 12 improved, 16 did not, and 10 gave up. |

| Braun 201990 | Patients with MDD (N = 20) | An open-label, single-group pilot study listened to instrumental tracks designed to embed low-frequency sounds (30–70 Hz). | Of the 19 that completed the study, seven had significant and clinically relevant reductions, 12 had no significant changes, and one withdrew. |

| Sigurdardóttir 201991 | Patients with depression (N = 38) | An open-label randomized controlled pilot study; intervention group (IG; n = 18): HALF-MIS; control group (CG; n = 20): Standard therapy. | IG: Scores markedly decreased without side effects; CG: scores also decreased, but not as significantly as in the IG |

| Daengruan 202192 | Patients with mild to moderate acute depression (N = 18) | RCT; intervention group (IG): Standard therapy + music therapy; control group (CG): Standard therapy. | The PHQ-9 score was 1.50 (95% confidence interval: −4.46–1.46) lower in the IG than in the CG. The difference was nonsignificant (p = 0.32). EQ-5D and MARS scores did not differ significantly between groups. |

| Atiwannapat 201693 | Resident patients with MDD (N = 14) | A single-blinded randomized controlled trial

|

|

| Erkkilä 2008, 201194, 95 | 18–50-year-old patients with depression (N = 85) | A single-blind RCT; intervention group (IG): Psychodynamics music therapy + standard therapy; control group (CG): Standard therapy. | The IG improved more than the CG in general results, anxiety symptoms, and general function. The response rate was significantly higher in the IG than in the CG. |

| Erkkilä 2019, 202196, 97 | Adults with a primary MDD diagnosis | A 2 × 2 factorial RCT

|

RFB therapy had a significant overall effect, which was greater after adjusting for potential confounders. The effect of LH was nonsignificant. |

| Hartmann 202298 | Adults with a primary MDD diagnosis (N = 69) | Ditto | RFB participants showed greater MADRS score reductions and music interactions. |

| Nwebube 201799 | Pregnant women (N = 111) | RCT; intervention group (IG; n = 20): Listening to music; control group (CG; n = 16): Relax. | At the end of the study, EPDS scores improved in the IG but not the CG. |

| Ettenberger 2018100 | Mother and baby (N = 15) | A mixed-methods pilot study using concurrent triangulation and a within-subject repeated measures design; music therapy song creation; no control group. | Participants' scores on various scales improved. |

| Wulff 2021101 | Pregnant women (N = 120) | RCT; intervention group (IG; n = 59): Singing interventions; control group (CG; n = 61): No intervention. | In the IG, cortisol levels decreased significantly (p = 0.023), and emotional attachment and mood were improved (p ≤ 0.008). There was no apparent effect in the CG. |

| Cross 2012102 | Senior boarding and nursing staff (N = 100) | RCT; dance group (DG; n = 50): Live dance performance; music group (MG; n = 50): Listen to music. | Both groups improved after the intervention, but Beck depression scores were significantly lower and lasted longer in the DG. |

| Verrusio 2014103 | Patients with mild to moderate depression (N = 24) | RCT; drug treatment group (DT): Antidepressant treatment; exercise/music therapy group (E/M): Physical exercise and listening to music. | In the E/M group, depression and anxiety symptoms decreased significantly at three and 6 months (p < 0.05), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) levels decreased from 57.67 to 35.80 pg/ml. In the DT group, anxiety symptoms were significantly improved at 6 months. |

| Liao 2018104 | Community-dwelling older patients with mild to moderate depression (N = 112) | RCT; intervention group (IG; n = 57): 24-style Yang tai chi exercise with Chinese traditional folk music; control group (CG; n = 55): Routine health education. | All quality of life domains and depressive symptoms significantly improved in the IG. |

| Biasutti 2021105 | 62–95-year-old nursing inpatients with cognitive impairment but otherwise healthy (N = 45) | RCT; experimental group (EG; n = 20); control group (CG; n = 25). | The SDS improved significantly in the EG (T = 1.450; p < 0.005; D = 0.453), and cognitive levels were significantly higher in the EG than in the CG (T = 1.240; p < 0.05; D = 0.273). The CG did not improve significantly (T = 0.080; p > 0.10; D = 0.025). |

| Zhao 2021106 | Patients with MCI diagnosed with depressive symptoms (N = 70) | A quasi-experimental pilot study; intervention group (IG; n = 35, 31 completed): Square dancing + health education; control group (CG; n = 35, 32 completed): Health education. | The mean MoCA-P score increased, and the mean GDS-30 score decreased in the IG, whereas the mean MoCA-P and GDS-30 scores did not change over time in the CG. |

| Yao 2021107 | Community-dwelling patients with MCI and depressive symptoms | A mixed-method study with quantitative and qualitative phases on a public square dancing intervention. | Mental health and fatigue scores were increased at the 3-month follow-up. |

| Baker 2022108 | Large nursing home units (N = 20) | A 2 × 2 factorial cluster RCT

|

RCS worked better and had a lasting impact, whereas GMT was more beneficial for late-stage dementia. |

| Xue 2023109 | Older adults aged >65 years with MCI and depression symptoms (N = 80) | Intervention group (IG): Usual nursing care + a receptive music therapy intervention four times a week for 8 weeks; control group (CG): Usual nursing care over the same period. | Pre- and post-intervention cognitive function and depression scores differed significantly in the IG but not in the CG, with a significant between-group difference in both cognitive function and depression scores. |

| Iriagac 2021110 | Patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy for the first time in an outpatient clinic (N = 104) | A prospective, open-label RCT; intervention group (IG): An intervention waiting room; control group (CG): Standard waiting room. | Anxiety, HADS, and STAI scores were lower in the IG than in the CG. The average heart rate decreased in the IG. HADS and STAI scores increased with the waiting time. |

| Liou 2022111 | Hospitalized patients with cancer (N = 1764) | A retrospective, multi-method inpatient program: Music therapy (n = 350); massage therapy (n = 1414). | Both therapies relieved depressive symptoms, but music therapy provided greater relief. |

| Esfandiari 2014112 | Female college students with depressive disorder (N = 30) | Randomized controlled study

|

Depression levels decreased in both music groups but were greater in the light music group. |

| Yang 2022113 | College students with no or mild depressive symptoms (N = 94) | Randomized controlled study

|

3) Was better for individuals with mild depressive symptoms; 2) was better for individuals without depressive symptoms. |

| Geipel 2022114 | Teenagers with depression (N = 9) | A prospective, single-arm repeated-measures design on music therapy. | Music therapy improved depressive symptoms, health-related quality of life, and positive coping skills. |

| Park 202378 | 36 subjects with ADHD | Music therapy (MG): Music therapy + standard care; control group (CG): Standard care. | In the MG, 5-HT secretion increased, whereas cortisol levels, BP, and HR decreased. The CDI and DHQ psychological scales also showed positive changes. However, in the CG, 5-HT secretion did not increase, and cortisol levels, BP, and HR did not decrease. The CDI and DHQ psychological scales also did not show positive changes. |

| Shiranibidabadi 2015115 | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (N = 30) | A single-center, parallel-group RCT;

|

Music therapy significantly reduced the total obsessive-compulsive score and depression and anxiety symptoms. Standard treatment showed no significant effect. |

| Giordano 2022116 | Patients with Covid-19 (N = 40) |

|

|

| Shah-Zamora 2024117 | Patients with PD and their caregivers (N = 16) | Twelve, weekly virtual group music therapy sessions | Apathy and depression improved. |

| Chou 2024118 | Patients with subacute stroke (N = 82) | 1) MT group a conventional therapy (CT) group | MRS scores differed significantly between groups. |

| Lagattolla 2023119 | Patients hospitalized for breast surgery (N = 151) |

|

Both MT interventions were effective in reducing all the variables: Stress, depression, anger, and anxiety (p < 0.01). |

- Abbreviations: 5-HT, Serotonin; AG, active group music therapy; BP, blood pressure; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; CDI, Children's Depression Inventory; CG, control group; DG, dance group; DHQ, Daily Hassles Questionnaire; DT, drug treatment group; E/M, exercise/music therapy group; EG, experimental group; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; EQ-5D, Euro Quality of Life Five-Dimension; GDS-30, Geriatric Depression Scale; GMT, group music therapy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HALF-MIS, High Amplitude Low Frequency-Music Impulse Stimulation; HR, heart rate; IG, intervention group; IIMT, Integrative Improvisational Music Therapy; LH, Listening Homework; MARS, medication adherence rating scale; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MDD, major depression disorder; MG, music group; MoCA-P, Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Peking version; MRS, modified Rankin Scale; MTG, music therapy group; MTiGrp, group/active-receptive integrated; MTri, individual/receptive; O2Sat, Oxygen saturation; PG, psychotherapy group; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire depression screening; RCS, recreational choir singing; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RFB, Resonance Frequency Breathing; RG, receptive group music therapy; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

5.1 Different music therapy modalities

There are various forms of music therapy. They can be divided into active and passive types based on whether the participants actively participate. In active music therapy, patients can improvise, rewrite, or arrange the music. In contrast, in passive music therapy, patients listen to music chosen by the therapist at home or in the treatment room. Music therapy can be provided to patients individually or in groups. Several common music therapy modalities and their practical experiences are described below.

5.1.1 Passive music therapy

Passive music therapy, in which participants listen to music CDs, has been validated by several experimental studies over the past 20 years. The music can be assigned by the therapist or negotiated between the therapist and the patient. In this approach, since the patient does not need to be accompanied by a therapist to participate in the therapy, it can occur at a time and place of their choosing.

In 2004, Hsu and Lai used soft music to treat inpatients with MDD in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Their subjects listened to music of their choice for 2 weeks. They found music to significantly improve depression scores compared with the control intervention. Weekly improvements suggested a cumulative effect.88 In 2010, a randomized study by Castillo-Pérez et al. compared the effects of music and psychotherapy on depression in 79 patients aged 25–60 years with mild to moderate depression. The music therapy group (MTG) showed fewer depressive symptoms than the psychotherapy group, which proved to be statistically significant in the Friedmann test.89 In 2019, Braun Janzen et al. investigated the effects of a 5-week music intervention involving listening to music and rhythmic sensory stimulation on depression and its related symptoms in 20 patients formally diagnosed with MDD. Measures of depression and related symptoms significantly improved from pre-to post-intervention.90 In 2019, Agusta Sigurdardóttir et al. explored the stimulation of the vagus nerve in patients with depression using high amplitude low frequency–music impulse stimulation (HALF-MIS), finding that the experimental group (EG) reported decreased depressive symptoms. This approach was non-invasive and safe for the patient, and no side effects were reported.91 In 2021, Daengruan et al. compared embedded 10-hz binaural beats music therapy with standard therapy in patients with depression, finding no apparent differences in depression scores, quality of life, or drug compliance between groups, potentially because of the small sample size, individual differences, and short duration of the intervention.92

5.1.2 Group music therapy

In group music therapy, patients are formed into small groups for one-to-many sessions. Patients not only receive the benefits of music therapy but also socialize with others during therapy, which often benefits their condition.

In 2016, a Thai study compared two GMT interventions (active and passive) with group counseling in patients with MDD. They found that the passive MTG reached the peak treatment effect sooner, but the peak was not as high as in the active MTG. They concluded that GMT, whether active or passive, is an effective adjunctive therapy for outpatients with depression.93

Research on GMT is ongoing. In 2017, Elizabeth et al. began a study comparing GMT and waiting list-controlled therapy in community-dwelling patients with chronic depression.120 However, we could not find an article reporting the results of this study. Nonetheless, in 2020, Windle et al. surveyed 10 participants from three groups in the Elizabeth et al. study and found through semi-structured interviews that participants given the group-created music therapy found it engaging, safe, enjoyable, and liked creating with others.121

5.1.3 Improvisational music therapy

In improvised music therapy, participants can follow their hearts to express their emotions. Musical improvisation seems to elicit diverse and heightened emotional states.121

Erkkilä et al. began a study examining the effects of improvised music therapy on depression in 200894 and reported its results in 2011.95 They found that participants who received music therapy plus standard care showed greater improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and general function than those who received standard care. The effectiveness rate was significantly greater in the combined therapy group than in the standard therapy group.

Later, Erkkilä et al. began a study examining combined resonant frequency breathing (RFB) or listening (LH) with music therapy in different patient groups in 201996 and reported its results in 2021.97 They found that adding RFB to a music therapy intervention improved the treatment outcomes of patients with depression.

Subsequently, Hartmann et al. conducted a study based on Erkkilä et al.97 to explore the function of music interaction throughout the therapeutic process of improvisation.98 They found that groups with greater music interaction showed greater clinical improvement, indicating that the degree of music interaction is closely related to the treatment effect.

5.2 Treatment of depression caused by different pathogenic factors

5.2.1 Antenatal and postpartum depression

Antenatal and postpartum depression is painful for mothers and may adversely affect the fetus and its subsequent development. Therefore, identifying and improving depression symptoms in pregnant women and maternity is vital. Many women who breastfeed their children refuse pharmacological interventions to protect them. Psychological counseling may be effective, but due to economic and geographic factors, it is often unavailable for many women looking for help. As an accessible method, listening to music is beneficial and available to all women.99

In 2017, Nwebube et al. conducted a study in which they wrote songs dedicated to relieving depression and allowed some pregnant women to listen to them to see whether their prenatal depression symptoms decreased. They randomly assigned 111 participants to the music-listening or control group (CG), of whom 36 completed the 12-week treatment and completed a questionnaire. Their results showed that depression and anxiety symptoms decreased in the music-listening group over the 12 weeks but did not change in the CG. They concluded that regularly listening to relaxing music is an effective non-drug means to reduce prenatal depression and anxiety.99

In 2018, Ettenberger et al. explored the effects of songwriting on the mothers of premature infants in a neonatal intensive care unit in Colombia, measuring the effects of song composition on intimate relationships, depression, anxiety level, and mental health. Their results suggested that songwriting may be particularly effective for mothers at risk of relationship damage and those with anxiety or depression symptoms. Parents can express their feelings for their premature babies by creating a welcome song for them during their hospital stay, which can make the children relax and improve the communication skills of both parents and their children.100

In 2021, Wulff et al. conducted a prospective, randomized, controlled study on the effects of mothers' singing on happiness, postpartum depression, and intimacy among 120 women. Their results showed that, in the singing group, the more frequently the mother sang, the less anxious and happier she felt. Both subjective and physiological measures (salivary cortisol) indicated that singing to infants directly and positively affected the well-being of postpartum women.101

5.2.2 Cognitive impairment depression

With population aging, aging-related issues have drawn widespread attention. In addition to physical health, research into the mental health and emotional needs of older adults is also warranted. Depression has been observed extensively in patients with neurodegeneration, showing a close relationship between depression and cognition. Depression promotes biological aging by shortening telomere length, accelerating brain aging, and delaying epigenetic aging.122 Those with depression are more likely to suffer from medical conditions, which also increase the risk of depression later in life. Music interventions can help to alleviate cognitive decline in older adults, especially when these activities are performed within a group. A recent meta-analysis found that music therapy reduces depression and anxiety symptoms, improves BP, and enhances cognitive function in older patients with depression.123

In 2012, Cross et al. investigated the effects of music, dance, and exercise therapy on mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild to moderate depression in older adults. They examined the effects of passive listening to music and actively observing dance accompanied by music on memory enhancement and relief of depressive symptoms in 100 older residents at a board and care facility. Both groups improved after the intervention, but the BDI score was significantly lower and lasted longer in the dance group.102

In 2014, Verrusio et al. assessed the effects of music therapy on mild to moderate depression. Their results suggested that music may help control mood disorders and that improvements in mood appear to persist over time.103

In 2018, Liao et al. examined the effects of an intervention combining tai chi with music on depression in 112 community-dwelling older adults diagnosed with mild to moderate depression. They found that it provided noticeable relief from depressive symptoms and improvements in life quality.104

Biasutti et al. examined the validity of music training in relieving depression and improving general cognitive function in older adults. Music activities include improvisation exercises to stimulate interpersonal skills, emotions, and cognitive function. The results showed that GDS scores significantly improved in the EG but not in the CG. In addition, while cognitive levels, assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination, improved in both the experimental and control groups, the change was greater in the EG.105

In 2021, Zhao et al. examined how a nurse-led cube dance intervention program affected 35 older patients with MCI and depressive symptoms. Their results showed that depressive symptoms were significantly reduced and cognitive ability was significantly improved in the intervention group compared with the CG after treatment.106

Yao et al. examined the effects of a public square dancing intervention in 35 older adults with MCI and depression. Their mental health and fatigue scores both improved at the 3-month follow-up. Their results showed that the public square dancing intervention was acceptable, feasible, and valuable in improving the depressive symptoms of patients with MCI and could be conducted by community nurses.107

In 2022, Baker et al. conducted a two-factor cluster RCT to determine whether recreational choir and GMT were more effective than standard care in reducing depressive and other secondary symptoms in patients with mild to severe depression and dementia. Their findings suggested that group singing was particularly effective in improving clinical depression, psychiatric symptoms, and general quality of life.108

In 2023, Xue et al. assessed a receptive music therapy intervention in 80 older adults aged >65 years with MCI and found that it significantly improved their cognitive functioning and reduced their depressive symptoms. They suggested that it should be applied in the community and nursing homes to improve the quality of life of older adults.109

5.2.3 Cancer-induced depression

Cancer affects patients' physical function and psychological burden. The lives of patients with cancer involve significant pain, and chemotherapy adds to this pain. Depression and depressive moods are common in patients with cancer. Music-based interventions are expected to improve patients' moods and reduce their suffering. A recent review found that music therapy significantly reduces depression and anxiety in patients with breast, lung, prostate, and colorectal cancers and recommended that healthcare providers incorporate music therapy interventions when treating patients with cancer.124

In 2017, Chen et al. found that a group music intervention significantly and immediately reduced helplessness, despair, and anxiety pre-occupation in women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Moreover, it significantly reduced anxiety, depression, helplessness or despair, and cognitive avoidance.125

Iriagac et al. explored how placing attractive visual objects and playing music as an ambiance in the waiting room affected the anxiety levels of patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy for the first time in an outpatient clinic. Their results showed that anxiety scores were lower in the EG than in the CG. They concluded that waiting for chemotherapy in a waiting room decorated with green plants, beautiful paintings, and soothing music reduced the anxiety of patients with cancer.110

More recently, Liou et al. compared music therapy with massage therapy among 1764 hospitalized patients with cancer. They found that while both music and massage therapy could reduce depressive symptoms, music therapy was more effective.111

In 2023, Park et al. demonstrated the positive neurophysiological and psychological effects of music therapy as an alternative treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), finding that it activated serotonin and improved stress-coping skills.78

5.2.4 Adolescent depression

Genetic factors or family circumstances can cause depression in adolescents. Timely intervention during adolescence can reduce the risk of relapsing into depression in adulthood.

In 2014, Esfandiari et al. explored the effects of light and heavy music on adolescent depression. Thirty female students with depression were randomly divided into three groups: One listened to light music, one listened to heavy music, and one received no intervention. Those in both music listening groups reported decreased depression. After all interventions, the experimental groups scored significantly lower on the BDI than the CG.112 The decline in scores was more significant in the heavy music group.

Yang et al. examined how the effects of aerobic training differed between rhythmic and non-rhythmic music among 94 college students with no or mild depressive symptoms who received a 30-min randomized, balanced intervention. They found that the multi-mode intervention was more effective for mild depression, but single-mode aerobic training was more effective for depressive emotions in those without depression. This study proved that different interventions could be used to treat different levels of depression.113

Geipel et al. assessed the effects of 12 music therapy sessions in adolescents with depression at an outpatient center. Their results suggested a decrease in depressive symptoms and improvements in emotion regulation and health-related quality of life among participants. However, these beneficial effects did not appear to last long at the follow-up. They suggested that music therapy was not harmful to teenage patients with mild to moderate adolescent depression and may help to improve clinical outcomes.114

5.2.5 Other diseases with comorbid depression

Many patients with other diseases also suffer from depression, which in turn aggravates their condition and greatly affects their treatment. As an auxiliary treatment, music therapy can regulate patients' emotions. Positive emotions help patients to consider their therapy optimistically, which has a beneficial effect on disease treatment.

In 2015, Shirani Bidabadi et al. reported that music therapy appeared to effectively reduce depression symptoms in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Therefore, patients could use music to treat themselves as an adjunct to standard care.115

Depression is also common in patients with heart failure. Treatments for heart failure often fail to meet expectations due to patients' comorbidities. Depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and insomnia all increase the burden of patients with heart failure and affect their quality of life. In 2019, Burrai et al. examined the effects of listening to classical music on the depressive emotions, anxiety, quality of life, sleep, and cognitive status of patients with heart failure. Their results of patients in music group showed greater improvements in these areas compared to those of the CG.126

Chronic kidney disease is another hard-to-treat disease that affects many individuals. It severely impairs patients' quality of life and increases their likelihood of developing mood disorders. Patients must undergo hemodialysis regularly. In 2019, Burrai et al. examined how listening to nurses sing live during hemodialysis affected patients with end-stage renal disease. Their results showed that the music intervention regulated patients' moods and reduced their dialysis pain and risks of depression and anxiety.127

Migraine is an idiopathic and debilitating disease that significantly affects patients by disrupting their emotional relationships and daily activities. Migraine sufferers often have comorbid depression and anxiety. Parlongue et al. assessed a music intervention in patients with migraine and found that it could significantly prevent migraine attacks. It also significantly reduced patients' depression and anxiety symptoms.128

According to the World Health Organization, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to a 25% increase in the global prevalence of depression and anxiety.129 Increasing numbers of patients with COVID-19 have reported depressive symptoms of varying severity after recovering from the acute phase.130 Recently, Giordano et al. explored how a single session of music therapy affected the anxiety and life parameters of 19 inpatients with COVID-19 affected by varying degrees of depression disorder, stress, anxiety, and fear. Their results showed that a single music therapy session improved oxygen saturation (O2Sat) and significantly reduced anxiety.116

Hypertension, anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders are common in patients with hypertension. A recent review found that music therapy effectively controlled BP and HR, reduced anxiety and depression, and improved sleep quality in patients with hypertension.131

6 CONCLUSIONS

In recent years, while the number of studies using music-based interventions to treat depression has increased, these studies have been limited to local contexts. There is a lack of extensive research on the effects of culture, age, and individual musical preferences on the effectiveness of music therapy. It is well known that music and culture are intricately related, and cultures vary widely worldwide, raising the question of whether different music therapy traditions can be applied in different cultural contexts. Liao et al.132 explored whether a Chinese music therapy tradition (five elements music therapy [FEMT]) was effective in a Canadian setting and whether the Western art music therapy (WAMT) approach was effective in a Chinese setting. Their results showed that FEMT and WAMT had similar favorable effects in both Chinese and Canadian cohorts, including improved coping skills, reduced anxiety-provoking thoughts, and improved sleep. However, very few cross-cultural studies have been reported. In the future, more extensive experiments and studies are expected to address this gap.

Depression is a common mood disorder. Whether it is a first episode or a relapse, patients with depression often suffer greatly and are at risk of suicide; therefore, early and aggressive treatment is necessary. A physician generally diagnoses depression according to the DSM-5 criteria using various scales as aids. In recent years, there has been an increase in research using EEG or brain MRI to confirm the depression diagnosis, but it has not yet been clinically conclusive. There are two main types of treatment for depression: medication and psychotherapy. However, both approaches have their drawbacks. As a non-invasive treatment for depression, music therapy is effective and easily accessible. It will not increase the burden on patients, their families, and medical workers. Therefore, it has great prospects. While the number of studies on music-based treatments for depression has increased in recent years, some uncertainties in how to implement music therapy and its duration remain due to a lack of samples, individual differences, and the short implementation times of existing treatment practices. Further trials with more subjects and longer durations are needed to verify the efficacy of music therapy and arrive at a sustainable and effective treatment implementation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xiaoman Wang: Investigation; writing—original draft preparation. Wei Huang: Writing—review and editing. Shuibin Liu: Writing—review and editing. Chunhua He: Project administration. Heng Wu: Project administration. Lianglun Cheng: Project administration. Songqing Deng: Project administration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62104047, U22A2012 and 62173098), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2023A1515010291), and Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangzhou Basic Research Program (Grant No. 2023A04J1707).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not needed in this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.