Sustained inhibition of complement C1s with sutimlimab over 2 years in patients with cold agglutinin disease

Data first presented at the European Hematology Association annual meeting, June 9–12, 2021.

Clinical Trial Registration: This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03347396).

Abstract

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a rare, autoimmune, classical complement pathway (CP)-mediated hemolytic anemia. Sutimlimab selectively inhibits C1s of the C1 complex, preventing CP activation while leaving the alternative and lectin pathways intact. In Part A (26 weeks) of the open-label, single-arm, Phase 3 CARDINAL study in patients with CAD and a recent history of transfusion, sutimlimab demonstrated rapid effects on hemolysis and anemia. Results of the CARDINAL study Part B (2-year extension) study, described herein, demonstrated that sutimlimab sustains improvements in hemolysis, anemia, and quality of life over a median of 144 weeks of treatment. Mean last-available on-treatment values in Part B were improved from baseline for hemoglobin (12.2 g/dL on-treatment versus 8.6 g/dL at baseline), bilirubin (16.5 μmol/L on-treatment versus 52.1 μmol/L at baseline), and FACIT-Fatigue scores (40.5 on-treatment versus 32.4 at baseline). In the 9-week follow-up period after sutimlimab cessation, CP inhibition was reversed, and hemolytic markers and fatigue scores approached pre-sutimlimab values. Overall, sutimlimab was generally well tolerated in Part B. All 22 patients experienced ≥1 treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE); 12 (54.5%) patients experienced ≥1 serious TEAE, including seven (31.8%) with ≥1 serious infection. Three patients discontinued due to a TEAE. No patients developed systemic lupus erythematosus or meningococcal infections. After cessation of sutimlimab, most patients reported adverse events consistent with recurrence of CAD. In conclusion, the CARDINAL 2-year results provide evidence of sustained sutimlimab effects for CAD management, but that disease activity reoccurs after treatment cessation. NCT03347396. Registered November 20, 2017.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a rare type of autoimmune hemolytic anemia characterized by chronic hemolysis mediated by activation of the classical complement pathway (CP).1, 2 CAD is a mature B-cell neoplasm, as defined by the International Consensus Classification and the World Health Organization Classification of Hematolymphoid Neoplasms (5th edition), resulting in production of cold agglutinins; 90% are immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies.1, 3-5 Cold agglutinins in CAD usually bind to the I antigen on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs) by nonionic interactions that are weak at temperatures approaching body temperature and grow stronger at low temperatures.1, 6 The pentameric structure of the cold agglutinins allows a lattice of clustered RBCs to form.7 IgM-antigen binding leads to activation of the CP, predominantly resulting in extravascular hemolysis through the mononuclear phagocytic system in the liver and often, to a lesser extent, intravascular hemolysis via the membrane attack complex.2 Understanding the underlying mechanisms behind CAD raises the possibility that targeting aspects of the complement system may be a promising therapeutic strategy.8, 9 Clinical manifestations of CAD are twofold: chronic hemolytic anemia and profound fatigue resulting from chronic activation of the CP, and RBC agglutination-mediated circulatory symptoms such as acrocyanosis or Raynaud's phenomenon.10 By definition, all patients with CAD have chronic hemolysis with or without anemia.11 CAD is also associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events and mortality.6, 12, 13

Sutimlimab is the first approved pharmacotherapy for the treatment of patients with CAD.14 Sutimlimab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents CP activation by targeting C1s; the alternative and lectin pathways of complement are left intact.15, 16 Sutimlimab's safety and efficacy for the treatment of patients with CAD have been demonstrated in a Phase 1b trial, subsequent extensions, and two pivotal Phase 3 studies.16-20 In Part A of the open-label, single-arm, CARDINAL study of sutimlimab in patients with CAD and a recent history of transfusion, sutimlimab rapidly halted hemolysis, improved hemoglobin (Hb) levels, and reduced fatigue over 26 weeks.15 In Part A of the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, CADENZA study of sutimlimab in patients with CAD with no recent history of transfusion, sutimlimab, but not placebo, led to improvements in mean Hb levels and markers of hemolysis, and clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue that were sustained over 26 weeks.17

Here, we report the findings from Part B of the CARDINAL study, including the 9-week posttreatment follow-up period, to understand the safety and tolerability of sutimlimab and the durability of response during long-term treatment.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and patient population

CARDINAL (NCT03347396) was a Phase 3, open-label, single-arm study comprising a 6-week screening and observation period, a 26-week treatment period (Part A), and a 2-year extension (Part B) after the last patient finished Part A. Full details of the CARDINAL study design have previously been published.15

Briefly, sutimlimab was administered by intravenous infusion of 6.5 g in patients weighing <75 kg or 7.5 g in those weighing ≥75 kg at Day 0, 7, and then every 2 weeks during Part A and every 2 weeks from Week 27 during Part B. Patients received RBC transfusions during Part A or Part B at Hb levels <9 g/dL if combined with clinical symptoms of anemia, or at Hb <7 g/dL even if they were asymptomatic. Patients who received an RBC transfusion during Part A were not withdrawn from the study and remained eligible to enroll in Part B. All ongoing patients receiving treatment in Part B entered a 9-week follow-up period after cessation of sutimlimab treatment (i.e., upon scheduled or premature completion of Part B), to return for an end-of-study visit 9 weeks after last dose (early termination [ET]/safety follow-up [SFU]).

2.2 Patients

Adult male and female patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CAD, screening Hb level ≤10.0 g/dL, and a recent history of RBC transfusion (within 6 months before inclusion) were eligible for the study. Screening bilirubin level had to be above the normal reference range and screening ferritin level above the lower limit of normal. A confirmed diagnosis of CAD was defined as the presence of chronic hemolysis, positive polyspecific direct antiglobulin test (DAT), monospecific DAT strongly positive for C3d, a cold agglutinin titer ≥64 at 4°C, IgG DAT ≤1+, and no evidence of overt malignant disease. Patients were also required to have symptomatic disease within 3 months of screening to be eligible for enrollment, defined as one or more of the following: symptomatic anemia (i.e., fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, palpitations, rapid heartbeat, light-headedness, and/or chest pain), acrocyanosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, hemoglobinuria, disabling circulatory symptoms, and/or major adverse vascular event (including thrombosis). Eligibility criteria included bone marrow biopsy findings (clonal lymphoproliferation ≤10% or absent; no evidence of overt lymphoma or other hematologic malignancy) within 6 months of screening, as well as vaccination against encapsulated bacterial pathogens (Neisseria meningitis, including serogroup B meningococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, where available, and Streptococcus pneumoniae), within 5 years of enrollment in accordance with regional guidelines. Where no regional guidelines were available, the vaccinations were to be initiated on Day 42 or as early as possible during the screening period. Patients were required to receive blood transfusions during the study if they met the transfusion criteria.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had: cold agglutinin syndrome secondary to infection, rheumatologic disease, or active hematologic malignancy; diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or other autoimmune disorders with antinuclear antibodies at screening; erythropoietin deficiency; or any clinically relevant infection within the month preceding enrollment. Patients were also excluded from the study if they had received treatment with rituximab monotherapy within the previous 3 months or rituximab combination therapies (e.g., with bendamustine, fludarabine, ibrutinib, or cytotoxic drugs) within 6 months prior to enrollment; concurrent treatment with corticosteroids, other than a stable daily dose equivalent to ≤10 mg/day prednisone, for 3 months prior to enrollment; or concurrent iron supplementation, unless they had received a stable dose for ≥4 weeks.

Patients were free to withdraw from the study at any time. The investigator could remove a patient from the study, if, in the investigator's opinion, it was not in the patient's best interest to continue.

The study protocol, any amendments, and patient-informed consent were written according to the Declaration of Helsinki and conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and the study was approved by local independent ethics committees or review boards. All patients provided written informed consent for their participation in the study.

2.3 Key endpoints and statistical analysis

In CARDINAL Part B, long-term efficacy, safety, and durability of response were assessed for up to 2 years after the last patient finished Part A.

Efficacy endpoints included disease-related markers (e.g., Hb, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin, reticulocytes) and quality-of-life assessments (e.g., Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy [FACIT]-Fatigue). The Wieslab® Complement System Classical Pathway assay was used to determine CP activity. Continuous data up to the sampling timepoint closest to 2 years in Part B (Week 135), mean last-available on-treatment values, as well as end-of-study data 9 weeks after the last dose of sutimlimab are reported here. Symptomatic anemia was assessed by the investigator throughout the study, defined as the presence of one or more of the following symptoms: fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, palpitations/rapid heartbeat, light-headedness, and/or chest pain.

To characterize safety, study investigators recorded incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and treatment-emergent serious adverse events (TESAEs), including adverse events (AEs) occurring during the 9-week off-treatment period following cessation of sutimlimab. Changes in clinical laboratory tests, including SLE panel parameters, and other health evaluations (e.g., physical examination, vital signs, and electrocardiogram findings) were also recorded. The evaluation of pre-existing antidrug antibody (ADA) and treatment-emergent ADA was collected throughout the study. AEs were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Organ Class and Preferred Term version 24.0. Safety data were recorded for the full duration of CARDINAL Part B, including the 9-week off-treatment period following cessation of sutimlimab.

Data were summarized using standard summary statistics for continuous and categorical data; haptoglobin levels of <0.2 g/L were imputed as 0.2 g/L in calculations. Percentages are based on the number of patients with nonmissing data in the Full Analysis Set, which includes all patients who enrolled into the Part B study and received ≥1 dose of sutimlimab. Efficacy data were reported in the Full Analysis Set and safety data were reported in the Safety Analysis Set. In Part B of the CARDINAL study, the Full Analysis Set and the Safety Analysis Set were identical.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

Of the 24 patients enrolled at the start of the CARDINAL study, 22 completed Part A and continued in Part B, with 19 patients completing the study. Overall, most patients were female (n = 15, 68%) with a median age at baseline (BL) of 71.5 years (range 55–85 years), the mean (standard deviation [SD]) BL Hb level was 8.6 (1.7) g/dL, and the mean (SD) BL FACIT-Fatigue score was 32.4 (10.9). BL patient demographics and disease characteristics of the Part B cohort are detailed in Table S1.

3.2 Efficacy endpoints

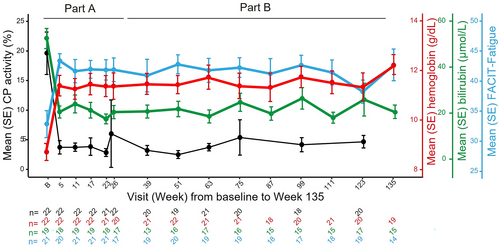

In Part B, patients received a median (range) of 144 (54–177) weeks of sutimlimab treatment. Sutimlimab treatment led to rapid and sustained increases in Hb levels (Figure 1). Mean (standard error [SE]) Hb increased 1.35 (0.27) g/dL from BL by Week 1; Hb levels >11 g/dL were maintained from Week 5 to Week 135. Mean (SE) last-available on-treatment Hb levels were 12.23 (0.33) g/dL; a mean (SE) increase of 3.59 (0.47) g/dL from BL.

Bilirubin levels were normalized with sutimlimab treatment (Figure 1). Decreases in mean total bilirubin were observed from Week 1; mean total bilirubin was normalized below 20.5 μmol/L from Week 3 to 135 with occasional excursions. Mean (SE) last-available on-treatment bilirubin levels were 16.45 (1.56) μmol/L.

Sutimlimab treatment led to clinically meaningful improvements in FACIT-Fatigue scores (Figure 1). Mean FACIT-Fatigue scores improved within 1 week; improvements in mean FACIT-Fatigue scores were consistent with a clinically meaningful change (≥5) and sustained through Week 135.21 Mean (SE) last-available on-treatment values for FACIT-Fatigue were 40.50 (1.99); a mean (SE) increase of 8.30 (2.84) from BL.

In addition, improvements were seen in additional markers of hemolysis including absolute reticulocyte count (BL mean [SE]: 143.1 [15.6] × 109/L; Week 135: 85.4 [21.4] × 109/L), haptoglobin levels (BL mean [SE]: 0.21 [0.01] g/L; Week 135: 0.38 [0.08] g/L), and LDH (BL mean [SE]: 452.7 [62.2]; Week 135: 311.9 [41.0] U/L).

Improvements in Hb, bilirubin, and FACIT-Fatigue correlated with near-complete inhibition of CP activity (Figure 1). Accordingly, reductions in hemolytic activity of the CP (CH50) compared with BL and normalization of complement component C4 levels were sustained at the last on-treatment visit (Figure S1).

Sutimlimab reduced the incidence of solicited symptomatic anemia. At BL, 72.7% of patients had one or more of the seven anemia symptoms that were regularly assessed per protocol (fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, palpitations, rapid heartbeat, light-headedness, and/or chest pain), which was reduced to ≤45% throughout Part B.

3.2.1 Observations from the 9-week post-treatment follow-up period

Overall, 19 patients completed Part B without an early termination, including 18 patients who completed the SFU visit and one patient who died during the follow-up period, due to exacerbation of CAD approximately 1.5 months after receiving the last dose of sutimlimab and so did not complete the SFU visit. Two patients who discontinued the study in Part B completed an ET visit.

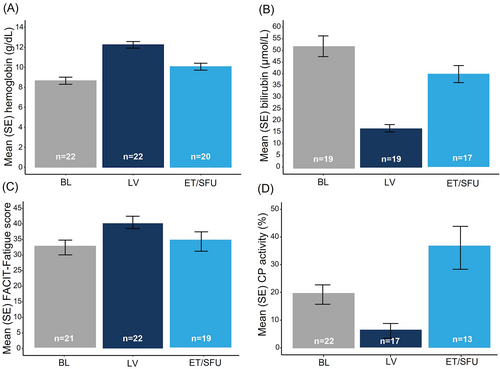

At the end-of-study visit (ET/SFU), 9 weeks after the last dose of sutimlimab, mean HB decreased by 2.28 g/dL from the end of Part B treatment (n = 20) but was still greater versus BL by 1.21 g/dL (Figure 2A). Mean total bilirubin increased by 24.27 μmol/L at the end of the study compared with the end of treatment in Part B (16.45 μmol/L) but was lower than BL by 9.98 μmol/L (Figure 2B). At the end of the study, 9 weeks after the last dose of sutimlimab, mean (SE) FACIT-Fatigue scores returned to close-to-BL levels at 34.11 (3.29) points (n = 19), with a mean (SE) change from BL of 1.05 (1.87) (Figure 2C). At the end-of-study visit, 9 weeks after the last dose of sutimlimab, the levels of several pharmacodynamic markers of complement activity returned to near BL levels (Figure 2D, Figure S1); C1q levels generally remained unchanged throughout the study period.

Similar effects were observed with other hemolytic markers at the end-of-study visit, 9 weeks after the last dose of sutimlimab (Figure S2): mean (SE) haptoglobin levels decreased to 0.23 (0.03) g/L from 0.40 (0.08) g/L at the end of treatment in Part B; a similar level was seen at BL. LDH returned toward BL with an increase of 47.5 U/L from the end of treatment in Part B. Mean reticulocyte count increased by 53.7 × 109/L (range: −16.6 to 250.4) from the end of Part B treatment and was comparable to the BL level (decrease by 0.6 × 109/L from BL).

3.2.2 Safety

All 22 patients experienced ≥1 TEAE during Part B (Table 1). Twelve patients experienced ≥1 serious TEAE, with two patients experiencing serious events assessed as related to sutimlimab treatment by the investigator (vitreous hemorrhage [n = 1] and viral infection [n = 1]).

| Total (N = 22) | |

|---|---|

| TEAEs, N | 380 |

| Patients with ≥1 TEAE, n (%) | 22 (100) |

| Patients with ≥1 relateda TEAE, n (%) | 11 (50) |

| TESAEs, N | 37 |

| Patients with ≥1 TESAE, n (%) | 12 (55) |

| Patients with ≥1 related TESAE, n (%) | 2 (9) |

| Patients with ≥1 TESAE infection, n (%) | 7 (32) |

| Total number of TEAE thromboembolic events, N (%) | 2 (9) |

| Patients who discontinued treatment and/or the study due to a TEAE, n (%) | 3 (14) |

| Deaths, n (%) | 2 (9)b,c,d |

- Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; N, number of patients; n, number of subjects; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TESAE, serious TEAE.

- a Considered related to sutimlimab by the investigator, AEs with missing causality assessment are also included in the related TEAE count.

- b One patient died after premature discontinuation of treatment with sutimlimab due to AEs (Klebsiella pneumoniae infection, acrocyanosis).

- c One patient died due to exacerbation of CAD during the follow-up period after completion of the treatment phase in the study.

- d Both events with fatal outcome were considered not related to sutimlimab by the investigator.

Serious infections were reported in seven (31.8%) patients including four patients who experienced serious infections with encapsulated bacteria, which are further described in the following. There were two cases of sepsis, one case caused by Escherichia in a patient with a history of cholelithiasis, and another case in the context of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with multiple comorbidities (including biclonal gammopathy and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma stage IV [recorded in medical history since 2015]), which was triggered by Streptococcus pneumoniae, an encapsulated bacterium for which vaccination was required per protocol. One patient experienced a bacterial urinary tract infection caused by Klebsiella. One fatal infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae occurred in a patient hospitalized with worsening general condition and acrocyanosis; sutimlimab was prematurely withdrawn (study day 763), and 14 days after the last dose of sutimlimab, the patient died due to Klebsiella pneumonia. Most of the serious infections occurred in patients with risk factors for infection (aspiration, diabetes mellitus, secondary Ig deficiency, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma stage IV, prednisolone treatment, and urinary catheter). All patients who experienced serious infections with encapsulated bacteria experienced ≥1 hemolytic breakthrough event (rapid fall in Hb ≥2 g/dL associated with an increase in LDH/bilirubin and/or decrease in haptoglobin); hemolytic breakthrough occurred in the patient during the Escherichia sepsis infection. Sutimlimab was either continued as planned or temporarily interrupted for all events of infection except for the fatal infection of Klebsiella pneumoniae where it was permanently discontinued. No patients experienced meningococcal infections or meningitis. No patients developed SLE, serious hypersensitivity, or anaphylaxis during the study.

Two patients (9.1%) had a thromboembolic TEAE; one nonserious device-related thrombosis due to an indwelling catheter and one TESAE of peripheral artery thrombosis of the left fourth digit. Both events resolved, were assessed by the investigator as unrelated to sutimlimab, and did not lead to discontinuation of treatment or withdrawal from the study.

One patient had a transient-positive treatment-induced ADA detected at Week 99. The pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) in this patient were not impacted.

Three patients (13.6%) discontinued the study due to AEs: acrocyanosis and Klebsiella pneumoniae infection (n = 1), vitreous hemorrhage in a patient with a history of recurrent uveitis and latent tuberculosis (n = 1; assessed by the investigator as related to sutimlimab); and acrocyanosis and gastrointestinal symptoms including erosive gastritis (n = 1; assessed by the investigator as related to sutimlimab).

Forty-five AEs occurred in 11 patients during the 9-week follow-up period. Of these, eight patients experienced AEs that were consistent with the recurrence of CAD, reported as anemia in four patients, ‘worsening of CAD’ in three patients, and hemolysis in one patient. In addition, acrocyanosis was reported in two patients. A serious AE of noncardiac chest pain was reported in one patient. One patient developed treatment-induced ADA at ET/SFU with a low titer; this patient did not have any other positive ADA response throughout the treatment period and ADA did not impact PK and PD. Two patients died during the 9-week off-treatment observation period following cessation of sutimlimab, one of whom was a patient with fatal bacterial pneumonia (Klebsiella pneumoniae). The other patient, with a femoral neck fracture and a complex medical history including myelodysplastic syndrome, died from exacerbation of CAD approximately 1.5 months after receiving the last dose of sutimlimab. Both events with fatal outcome were considered not related to sutimlimab by the investigator.

4 DISCUSSION

Sutimlimab is a first-in-class selective inhibitor of the CP.15 The final results of the Phase 3 CARDINAL study comprise data acquired over a median of >33 months of sutimlimab treatment and demonstrate that the rapid effects of sutimlimab treatment on hemolysis, anemia, and quality of life are sustained long term in patients with CAD who continue with therapy. Effects on Hb, bilirubin, and FACIT-Fatigue were maintained throughout a treatment period of more than 2 years. As previously published,15 BL FACIT-Fatigue scores were similar to scores seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis,22 advanced cancer-related anemia,23 or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.24, 25 Sutimlimab treatment led to clinically meaningful changes in FACIT-Fatigue scores (≥5-point change), which were sustained throughout the treatment duration.21 In the 9-week follow-up period after cessation of sutimlimab treatment, CP inhibition was reversed, and hemolytic markers and fatigue scores approached pre-sutimlimab values, indicating the recurrence of CAD after treatment discontinuation.

Overall, sutimlimab was generally well tolerated over 2 years of treatment. The type and frequency of TEAEs were generally consistent with an older, medically complex population. Most infections were reported in patients with risk factors for infection. Serious infections were reported; however, no meningococcal infections were recorded. No patients developed SLE, serious hypersensitivity, or anaphylaxis during the study. Treatment-induced ADAs were noted in two (9.1%) patients (n = 1, Part B treatment period; n = 1, 9-week follow-up period), with no notable effects observed on the PK and PD of sutimlimab, which indicates the low immunogenic potential of the drug. During the 9-week follow-up period after cessation of sutimlimab treatment, most of the patients reported AEs that were consistent with recurrence of CAD.

The CARDINAL study is limited by its single-arm design and low patient numbers, as may be expected for a rare disease such as CAD. It is also important to note that haptoglobin is a highly skewed parameter in patients with any type of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. This is also evident in our data set by the variability shown in mean (SD) haptoglobin at the end of Part B of 0.40 (0.40) g/L; this mean value corresponds with the lower limit of the normal range (0.40–2.40 g/L).

5 CONCLUSION

This study has demonstrated a continued favorable, long-term risk–benefit profile of sutimlimab for the management of patients with CAD over 2 years. Upon discontinuation of sutimlimab, treatment effect declined, and the symptoms of CAD reoccurred.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had access to primary clinical trial data, had full editorial control of the manuscript, and provided their final approval of all content.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the investigators, healthcare providers, research staff, and patients who participated in the CARDINAL study. Medical writing and editing support were provided by Blake Thornley of Lucid Group Communications Ltd. This support was funded by Sanofi. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by Sanofi (Waltham, MA). Sanofi reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

AR has received research support from Roche and received honoraria from and provided consultancy to Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bioverativ, a Sanofi company, BioCryst, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. WB has received honoraria from Sanofi. SDS has received research support from Janssen, honoraria from BeiGene, Janssen, and Sanofi, and partook in advisory boards with meeting expenses covered for Sanofi. YM has received honoraria and research support from Sanofi. CMB has received research support, honoraria from Sanofi as well as partaking in advisory boards and consultancy work on their behalf. MM has received either consultancy or speaker fees from Amgen, Argenx, Novartis, Sanofi and Sobi. DJK has received research support from Agios, Alnylam, Argenx, BioCryst, Incyte, Immunovant, Kezar, Principia, Takeda, and USB, and provided consultancy for Alexion, Agios, Alnylam, Amgen, Argenx, BioCryst, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caremark, CRICO, Daiichi Sanoko, Dova, Genzyme, Immunovant, Incyte, Kyowa-Kirin, Merck Sharp Dohme, Momenta, Novartis, Pfizer, Platelet Disorder Support Association, Principia, Rigel, Sanofi, Shionogi, Takeda, UCB, Up-To-Date, and Zafgen. BJ has been reimbursed for travel costs and scientific advice from Sanofi. THAT has participated in advisory boards for Janssen, Novartis, and Sobi. ICW has nothing to disclose. SB has received research support from Sanofi, received royalties from Up-To-Date, provided consultancy for Annexon, Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and Sobi and received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag and BeiGene. RY, DJ, KK, FS, MW, and ML are employees of Sanofi. DSV is an employee of IQVIA; provided analysis of safety data and support under contract with Sanofi.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained prior to the conduct of any study-related procedures.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level data and related study documents, such as the clinical study report, study protocol (with amendments), statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Of note, patient-level data will be anonymized, and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants. Further information related to Sanofi's data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at: https://www.vivli.org/.