US grass-fed beef premiums

Abstract

This study examined monthly retail-level price premiums for grass-fed beef (relative to conventional grain-fed beef) in the United States from 2014 through 2021. We found that premiums were heterogeneous, with premium cuts, such as sirloin steak, tenderloin, ribeye and filet mignon enjoying the highest premiums. Premiums were not consistent with price levels, as the lowest premiums were observed for short ribs, skirt steak and flank steak. Our findings suggest that grass-fed beef price premiums were negatively affected by the consumption of food away from home. Changes in income, increased information about taste, protein and minerals, fat, revocation of the USDA grass-fed certification program in 2016 and COVID-19 pandemic, also affected premiums for several individual cuts. Premiums were not sensitive to changes in information about climate change. [EconLit Citations: Q11, Q13].

Abbreviations

-

- Abr.

-

- abbreviation

-

- ADF

-

- augmented Dickey–Fuller test

-

- AR(1)

-

- an autoregressive process in which the current value is based on one preceding value

-

- BIC

-

- Bayesian information criterion

-

- CDC

-

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention

-

- CLA

-

- conjugated linoleic acid

-

- CLIM

-

- the number of published articles in the US newspapers, with keywords climate change” or “greenhouse gas” or “global warming” and “cattle”

-

- COVIDt

-

- an indicator variable for the post-national emergency declaration of COVID-19 pandemic period.

-

- COVID-19

-

- coronavirus disease of 2019

-

- CV

-

- coefficient of variation

-

- D.FAFH

-

- annual difference of food away from home's share of food expenditure

-

- D.LCLIM

-

- annual log-differences of CLIM

-

- D.LFAT

-

- annual log-differences of FAT

-

- D.LINC

-

- annual log-differences of real (in 2012 dollars) disposable personal income

-

- D.LPM

-

- annual log-differences of PM

-

- D.LTAS

-

- annual log-differences of TAS

-

- FAFH

-

- food away from home

-

- FAFHS

-

- nominal monthly sales of food away from home, seasonally adjusted

-

- FAH

-

- food at home

-

- FAHS

-

- nominal monthly sales of food at home, seasonally adjusted

-

- FAT

-

- the number of published articles, searched by key words “fat or cholesterol or heart disease or arteriosclerosis” and “diet” and “beef”

-

- FGLS-AR(1)

-

- pooled feasible GLS estimators with a heteroskedastic error structure with cross-sectional correlation and AR(1) autocorrelation structure

-

- FooDS

-

- Food Demand Survey

-

- FRED

-

- Federal Reserve Economic Data

-

- GLS

-

- generalized least-squares

-

- GMO

-

- genetically modified organism

-

- INC

-

- real disposable personal income: per capita, monthly, seasonally adjusted annual rate

-

- KPSS

-

- Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, Shin tests

-

- OLS

-

- ordinary least squares

-

- PCB

-

- conventional beef price

-

- PGF

-

- grass-fed beef price

-

- PGLS-PCSE

-

- pooled feasible GLS estimators with panel-corrected standard errors

-

- PM

-

- the number of published literatures, searched by key words “zinc” or “iron” or “protein” and “beef”

-

- PP

-

- grass-fed beef (relative) price premium

-

- PP

-

- Phillips–Perron tests

-

- RCF

-

- raised carbon friendly

-

- REVt

-

- an indicator variable for the period following the revocation of “grass-fed” label by USDA in January 2016

-

- RPP

-

- raw price premiums

-

- SVS

-

- small and very small

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- TAS

-

- the number of published articles in the US newspapers, searched by keywords “taste” or “tasty” or “tender” or “juicy” or “flavor” or “savor” and “beef”

-

- USDA

-

- the US Department of Agriculture

-

- USDA-AMS

-

- the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service

-

- USDA-ERS

-

- the US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service

-

- US

-

- the United States

1 INTRODUCTION

Consumer demand for specialized markets of healthier and environmentally friendly goods is on the rise, with large supermarket chains continually increasing their assortment of organic and ecofriendly products (Wong et al., 2010). Grass-fed beef is one of the production claims, along with naturally raised (raised without antibiotics and/or hormones) and certified organic, that aims to distinguish these products from conventionally raised grain-fed beef. Buoyed by growing interest among American producers and consumers, the grass-fed beef market has gained traction as a rapidly growing niche market (see Gillespie et al., 2016; McCluskey et al., 2005). The US grass-fed beef retail sales increased from less than $5 million in 1998 to $400 million in 2012 (Qushim et al., 2018; Williams, 2013). According to Nielsen data published in a report by Bonterra Partners, retail sales of grass-fed beef doubled every year from 2012 to 2016, growing from $17 million to $272 million (Bayless, 2018; Cheung et al., 2017). While the grass-fed beef market has been rapidly growing, it remains a relatively small portion of the beef market. In 2019, only about 4% of total beef sales were marketed with some type of label claim (Cattlemen's Beef Board, 2020). Moreover, beef products classified as grass-fed accounted for less than 2% of total retail beef volume (Cattlemen's Beef Board, 2020). This pattern of rapid growth and a small current market share points to a strong growth potential of the grass-fed beef market.

Consumer interest in grass-fed beef is motivated by a number of factors. Chief among them is the belief that it offers more nutrition and is more environmentally friendly than conventional grain-fed beef (Cheung et al., 2017; Shinn & Pledger, 2021). Cheung et al. (2017) argue that some consumers believe that grass-fed beef has a lower total fat content, better omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acid ratio, higher levels of antioxidants, a lower risk of Escherichia coli infection, and higher levels of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a cancer fighter, making it a healthier meat. Other primary drivers of consumer demand for grass-fed beef include concerns regarding animal welfare, as well as concerns regarding the use of growth-inducing, subtherapeutic antibiotics and hormones. A study by Consumer Reports (2015) compared multidrug resistant samples in grass-fed and conventional beef, and found that the former had three times lower likelihood of containing multidrug resistant bacteria. Consumers are often concerned about environmental stewardship. A recent wave of information highlighting the regenerative aspects of grass-fed grazing has further prompted consumer interest in grass-fed beef (Cheung et al., 2017; Shinn & Pledger, 2021). If managed properly, grass-fed grazing has been shown to improve soil quality, promote the growth of healthy grasses, and sequester carbon in the ground to mitigate climate change (Shinn & Pledger, 2021). However, other studies show that soil carbon sequestration is unstable and reversible (Hayek & Garrett, 2018). Additionally, when combating environmental impacts, people are more interested in discussing plant-based products rather than grass-fed meat (Davis et al., 2022). Ultimately, grass-fed cattle of the right breed, produced at the highest standards, can result in beef that is more tender, well-marbled and better-tasting than grain-fed beef (Cheung et al., 2017). However, achieving this quality of grass-fed meat is rare, and it is important to note that few consumers are buying it just for its flavor, and many would still prefer the flavor of conventional beef over grass-fed (Umberger et al., 2002).

The growth of the grass-fed market has precipitated several studies focusing on consumer demand for grass-fed beef. For example, Cheung et al. (2017) concluded that “baby boomers” and others who care about health and fitness would be likely buyers of grass-fed beef. A 2014 survey by the Consumer Reports National Research Center also showed that when shopping for food, consumers feel that it is important that their purchases “support local farmers, protect the environment, support companies that treat workers well, provide better living conditions for animals, and reduce the use of antibiotics” (Consumer Reports, 2015, p. 6). Gwin et al. (2012) found that at baseline, uninformed consumers in Portland, Oregon, would pay $0.90–$0.94/pound more for grass-fed ground beef. Moreover, information about production and nutritional factors increased this premium. Similarly, Umberger et al. (2002) showed that 23% of US consumers are willing to pay a premium of $1.36 per pound for Argentine grass-fed beef relative to US grain-fed beef. Furthermore, Tonsor et al. (2018) found that media reports, especially those related to climate change and sustainability, could have a significant effect on meat demand by altering preferences. These examples show that consumer preferences for claims-based foods are typically elicited using the data from interviews, written surveys, and experimental auctions (see Alphonce & Alfnes, 2012; Lim et al., 2013; Steenkamp et al., 2010; Umberger et al., 2002, e.g.). However, these approaches may be riddled with hypothetical biases in survey and/or experimental design.

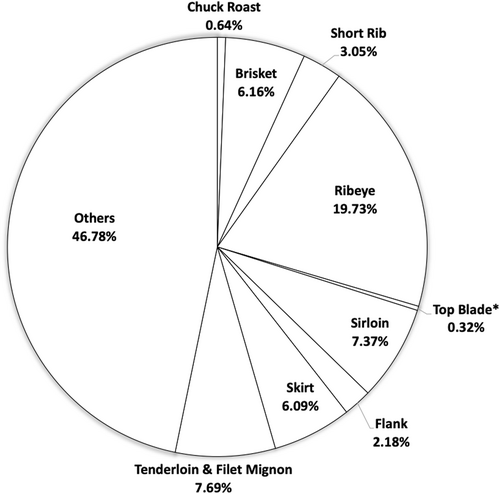

The goal of our study is to estimate premiums consumers paid for grass-fed beef based on observed national retail-level data from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)'s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) over the period 2014–2021. Our study explores the heterogeneity in premiums across the 12 most common cuts of grass-fed beef as well as the factors that affect these premiums. Figure 1 shows the relative shares of market sales across various beef cuts in 2021 indicating larger market shares of more expensive cuts, like ribeye, tenderloin and filet mignon. Thus, 10 out of 12 beef cuts that we discuss in this paper cover more than half of the total beef cut sales. To the best of our knowledge, market-based grass-fed beef premiums and premium variation across different cuts of beef have not been explored in the extant literature.

Consistent with the consumer-focused nature of our study, we explore the effects of consumers' real income, food consumption away from home, and media information on observed price premiums. Specifically, we assess the determinants of price premiums for each beef cut, both individually and jointly in a panel framework. Our findings indicate that the grass-fed beef price premiums were negatively affected by the consumption of food away from home. The premiums for some individual cuts were sensitive to changes in information about beef's protein, mineral, and fat content, its taste, the revocation of the USDA grass-fed certification program in 2016 and the COVID-19 pandemic. However, premiums were not sensitive to changes in information about climate change.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the conceptual framework. Section 3 offers a description of the data and the relevant sources. In Section 4, we present our empirical results and conduct relevant sensitivity analyses regarding our model specification. Our concluding remarks are presented in Section 5.

2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The relative price premium form (PP) will serve as the base of our analysis while the raw price premium measure (RPP) will serve as a test of robustness of our results.

Previous studies suggest that consumers' income positively affects premia in various niche markets, such as naturally produced beef (Umberger et al., 2009) and Raised Carbon Friendly (RCF) beef (Li et al., 2016). Specifically, Umberger et al. (2009) indicated that consumers with a higher income are more likely to pay a higher premium for natural products. Li et al. (2016) showed that higher-income consumers will support and pay more for RCF-certified beef.

Furthermore, Umberger et al. (2002) suggested that consumers' habit of eating at home is likely to affect the price premiums as well. Specifically, using survey data, Umberger et al. (2002) found that consumers who more frequently eat at home would prefer grass-fed beef steak to corn-fed beef steak. This suggests that food consumption patterns may affect price premiums. This factor may also be growing in relevance as Saksena et al. (2018) found that “over the past 30 years, FAFH's share of US households' food budgets and total food spending grew steadily.”

Beef has important nutrients including high-quality protein, iron, and zinc, which are potentially beneficial to good health for human beings (McAfee et al., 2010; Van Wezemael et al., 2014). Unsurprisingly, consumers' beliefs regarding beef's nutritional value and taste can also affect beef demand and price premiums (Tonsor et al., 2018). These beliefs are often influenced by media reports. In particular, information on the human health impacts of zinc, iron, and protein became prevalent. Additionally, medical journal articles linking nutrition including protein and minerals such as iron and zinc, have been positively linked to beef demand by Tonsor et al. (2010). Thus, more publications and media information on such nutritional elements leads to more consumer interest in products containing these characteristics. In this regard, Tonsor et al. (2010) found that the number of published articles related to fat negatively affected beef demand. Using a food demand survey (FooDS) from 2013 to 2017, Tonsor et al. (2018) argued that food taste is the most important food value and nutrition is the fourth most important food value to participating consumers. Furthermore, based on a rank of factors describing consumer perceptions regarding steak and ground beef, Tonsor et al. (2018) showed that “consumers, on average, perceive steak to be convenient, tasty, attractive, and novel but they also perceive steak to be poor for animal welfare, nutrition, and environment while also being expensive.” (p. 29)

Examination of grass-fed beef price premiums has to take into account relevant policy changes during the period of study. On January 12, 2016, the USDA revoked the “USDA Grass-fed” label, while leaving the standards for the claim on their website for producers to follow USDA-AMS (n.d.).3 At the same time, the USDA Grass Fed Small and Very Small Producer Program (SVS), administered by AMS, remained intact. Consequently, the AMS continued to collect and disseminate price information for meat products labeled grass-fed. The revocation meant that ranchers and restaurants became the third party certifying grass-fed beef. Yet little is known about whether the revocation of the USDA label affected the premiums for beef marketed as grass-fed. As such, we will explicitly investigate this issue in this study.

Another important market shock during the period of study was associated with COVID-19 pandemic. On January 20, 2020, the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US laboratory-confirmed case of COVID-19 of a domestic case in Washington state. By March 2020, cases were dispersed throughout the country. This culminated in the US Government declaring a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020.4 The pandemic led to a growth in demand for organic and sustainable foods worldwide (Ecovia, 2020) and in the United States (Askew, 2020). To the best of our knowledge, the effect of the pandemic on grass-fed beef premiums has not been explored in the previous literature, but will be explicitly examined in our study.

The vector of parameters captures the impact of the (annual) percentage changes of the exogenous variables on our grass-fed beef premium measure. The parameters and capture the impact of the grass-fed label revocation and COVID-19 pandemic, respectively. shows the effect of time trend, ; and denotes the error term.

We estimated Equation (6) using two approaches. First, we used OLS models to show the differential effects of the various factors on the grass-fed price premium for each individual cut. Second, we utilized a cut-panel estimation to examine whether these factors commonly affect price premiums.

3 DATA

Monthly retail price data for the 12 most common cuts of grass-fed and conventional beef from January 2014 to December 2021 were obtained from the National Monthly Grass-Fed Beef Report and USDA Weekly Retail Beef Feature Activity, respectively.6 Both are published by USDA-AMS.

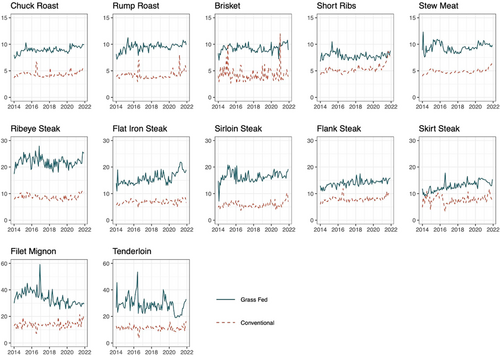

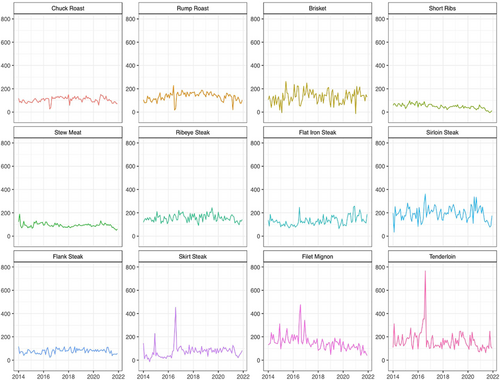

Figures 2 and 3 present the price levels (of grass-fed and conventional beef) and our computed premiums. Specifically, Figure 2 shows that the gap between the grass-fed and conventional beef varies over time and across cuts (ordered from least to most expensive). When expressed in premium terms, some more intriguing dynamics emerge. Figure 3 shows a decreasing trend in the beef premiums for some beef cuts (such as filet mignon and short ribs), whereas others (such as rump roast and chuck roast) exhibit an increasing trend before 2018 and a decreasing trend after 2018. Figure 3 also captures spikes in the premiums of expensive beef cuts such as filet mignon and tenderloin in 2016 due to the lower conventional beef prices shown in Figure 2.7

Table 1 corroborates these patterns. On average, the grass-fed beef premiums were between 48% and 193% of conventional beef prices. The “premium-quality” cuts seem to enjoy the largest average price premiums with sirloin steak (193.15%), tenderloin (165.46%), ribeye steak (156.08%), and filet mignon (150.02%) being the top contenders. Despite being some of the cheaper cuts of beef, roasts generated substantial premiums in the grass-fed beef market. The average premium for chuck roast and rump roast is as high as 105.54% and 132.80%, respectively. On the other hand, several cuts had average premiums of less than two times (100%) the conventional price. These include stew meat (93.39%), flank steak (77.31%), and skirt steak (74.72%). The lowest average premiums were observed for short ribs (48.25%). We interpret this as a signal that these cuts are less attractive (relative to others) in the grass-fed market. In general, these observations demonstrate heterogeneity in premiums of grass-fed beef cuts.

| Beef cuts | Filet mignon | Tenderloin | Ribeye steak | Sirloin steak | Skirt steak | Flat Iron steak | Flank steak | Rump roast | Brisket | Chuck roast | Short ribs | Stew meat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional prices ($/lb) | Mean | 13.98 | 11.20 | 8.66 | 5.76 | 7.72 | 6.93 | 7.98 | 4.16 | 4.30 | 4.41 | 5.38 | 4.89 |

| Median | 13.96 | 11.20 | 8.41 | 5.51 | 7.73 | 6.92 | 7.80 | 3.99 | 4.01 | 4.26 | 5.25 | 4.81 | |

| SD | 2.29 | 1.85 | 0.96 | 1.13 | 1.43 | 0.76 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 1.35 | 0.56 | 0.80 | 0.40 | |

| Grass-fed | Mean | 33.83 | 28.78 | 21.99 | 16.39 | 12.89 | 15.76 | 14.01 | 9.46 | 9.26 | 8.96 | 7.85 | 9.42 |

| Prices | Median | 32.89 | 28.62 | 22.02 | 16.17 | 12.96 | 15.14 | 13.98 | 9.54 | 9.29 | 8.91 | 7.79 | 9.40 |

| ($/lb) | SD | 5.26 | 5.83 | 1.93 | 1.89 | 1.79 | 2.21 | 1.21 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.82 |

| Price premiums (%) | Mean | 150.02 | 165.46 | 156.08 | 193.15 | 74.72 | 129.85 | 77.31 | 132.80 | 129.91 | 105.54 | 48.25 | 93.39 |

| Median | 143.01 | 144.09 | 154.51 | 192.08 | 71.16 | 121.38 | 79.79 | 139.78 | 136.11 | 110.41 | 47.67 | 92.73 | |

| SD | 66.35 | 85.88 | 30.45 | 58.39 | 56.26 | 39.91 | 19.95 | 35.90 | 55.13 | 22.60 | 20.03 | 18.41 | |

| CV | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.20 | |

| ADF without trends | −0.69 | −2.12 | −2.16 | −5.33*** | −2.35 | −1.66 | −1.11 | −1.08 | −2.42 | −2.07 | 0.47 | −2.68* | |

| PP without trends | −5.69*** | −7.23*** | −7.82*** | −7.56*** | −6.47*** | −6.1*** | −7.04*** | −6.33*** | −9.08*** | −5.76*** | −3.50*** | −5.42*** | |

| KPSS without trends | 0.64** | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.48** | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.78*** | 0.27 | |

| Annual change of price premiums | Mean | −12.77 | −6.36 | −0.32 | −3.20 | 1.70 | 3.91 | −0.68 | 0.48 | 6.24 | 0.37 | −6.09 | −2.59 |

| Median | −14.94 | −4.24 | −2.79 | −4.94 | 0.30 | 5.56 | 1.86 | 0.96 | 9.93 | 4.26 | −10.10 | 0.12 | |

| SD | 79.05 | 126.90 | 45.65 | 91.48 | 83.99 | 55.55 | 25.65 | 46.29 | 74.58 | 30.25 | 19.08 | 25.95 | |

| CV | −6.19 | −19.94 | −143.29 | −28.56 | 49.42 | 14.21 | −37.65 | 96.24 | 11.94 | 81.96 | −3.13 | −10.01 | |

| ADF without trends | −2.06** | −2.8*** | −3.5*** | −6.21*** | −2.87*** | −3.66*** | −1.52 | −1.74* | −3.28*** | −2.61** | −1.78* | −2.83*** | |

| PP without trends | −6.49*** | −6.33*** | −7.91*** | −5.92*** | −5.96*** | −5.81*** | −7.83*** | −7.5*** | −8.17*** | −5.61*** | −4.91*** | −4.39*** | |

| KPSS without trends | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.63** | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.08 |

- Note: Price premiums and annual changes are specified in Equations (2) and (9), respectively. The number of observations is 96. SD denotes the standard deviation and ADF denotes the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) tests. CV denotes coefficient of variation. The appropriate lag length is selected based on the BIC criterion. PP and KPSS are the Phillips-Perron and Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, Shin tests, respectively. The maximum lags of the KPSS test are chosen by Schwert criterion. *, **, and ***, reflect significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels of significance, respectively.

It is well documented that prices within the meat market are seasonal in nature (see Chavas & Mehta, 2004; Wang & Tomek, 2007, e.g.). Table 2 shows considerable seasonality in some cuts, especially brisket, with higher premiums both in the warmer (May, June, and August) and cooler (February, March, and November) months relative to January.8 Premiums for premium steaks, like filet mignon and tenderloin, were higher during the summer. On the other hand, premiums for flank steak and chuck roast were lower during the summer months. There is also evidence that premiums for filet mignon, tenderloin, as well as short ribs and stew meat, have declined over time.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation method | OLS | |||||||||||

| Beef cuts | Filet mignon | Tenderloin | Ribeye steak | Sirloin steak | Skirt steak | Flat iron steak | Flank steak | Rump roast | Brisket | Chuck roast | Short ribs | Stew meat |

| Trend | −1.27*** | −0.75** | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.27 | 0.56*** | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.09 | −0.51*** | −0.17** |

| (0.21) | (0.31) | (0.11) | (0.22) | (0.21) | (0.14) | (0.07) | (0.14) | (0.19) | (0.08) | (0.05) | (0.07) | |

| Feb | 12.83 | 35.60 | 29.32* | 3.69 | −16.74 | 3.90 | −0.29 | −3.19 | 61.37** | −26.88** | 4.54 | 4.33 |

| (28.65) | (41.71) | (15.02) | (30.26) | (28.80) | (18.22) | (9.70) | (18.66) | (26.00) | (11.32) | (7.12) | (9.17) | |

| Mar | 19.64 | 51.55 | 8.34 | 40.48 | −6.90 | 14.94 | 0.42 | −15.71 | 54.67** | −8.48 | 6.71 | −4.82 |

| (28.65) | (41.72) | (15.02) | (30.26) | (28.80) | (18.22) | (9.70) | (18.66) | (26.00) | (11.32) | (7.12) | (9.17) | |

| Apr | 27.76 | 12.55 | 3.44 | 19.87 | −13.16 | 4.29 | −2.08 | −6.79 | 19.77 | −10.56 | 4.08 | −1.53 |

| (28.65) | (41.72) | (15.02) | (30.27) | (28.80) | (18.22) | (9.71) | (18.67) | (26.00) | (11.32) | (7.12) | (9.18) | |

| May | 36.73 | 61.09 | −5.67 | 29.38 | −20.64 | 24.12 | −13.44 | 7.89 | 68.45** | −4.92 | 4.62 | −0.54 |

| (28.66) | (41.73) | (15.03) | (30.27) | (28.81) | (18.23) | (9.71) | (18.67) | (26.01) | (11.32) | (7.12) | (9.18) | |

| Jun | 25.88 | 70.99* | −17.00 | −6.16 | −13.54 | 33.72* | −18.78* | −4.13 | 70.86*** | −8.86 | 2.40 | 5.85 |

| (28.67) | (41.74) | (15.03) | (30.28) | (28.81) | (18.23) | (9.71) | (18.68) | (26.01) | (11.33) | (7.12) | (9.18) | |

| Jul | 51.87* | 40.63 | 9.36 | 37.45 | −4.90 | 23.04 | −19.05* | −13.87 | 31.70 | −20.85* | 7.91 | −4.80 |

| (28.67) | (41.75) | (15.03) | (30.29) | (28.82) | (18.24) | (9.71) | (18.68) | (26.02) | (11.33) | (7.13) | (9.18) | |

| Aug | 56.59* | 87.12** | −5.87 | 35.68 | 20.44 | 8.20 | −24.41** | −20.47 | 49.42* | −19.74* | 2.26 | 0.43 |

| (28.68) | (41.77) | (15.04) | (30.30) | (28.83) | (18.24) | (9.72) | (18.69) | (26.03) | (11.33) | (7.13) | (9.19) | |

| Sep | 16.67 | 16.53 | −14.33 | 16.41 | −6.50 | −7.26 | −9.59 | −1.95 | −0.31 | −6.73 | -6.88 | −5.62 |

| (28.70) | (41.78) | (15.05) | (30.31) | (28.85) | (18.25) | (9.72) | (18.70) | (26.04) | (11.34) | (7.13) | (9.19) | |

| Oct | 18.50 | 64.11 | −5.22 | 17.29 | −17.32 | −12.40 | −11.25 | 5.34 | 30.58 | −4.96 | −1.27 | −9.08 |

| (28.71) | (41.80) | (15.05) | (30.33) | (28.86) | (18.26) | (9.73) | (18.70) | (26.05) | (11.34) | (7.13) | (9.19) | |

| Nov | 25.68 | 13.49 | −5.67 | 20.13 | −13.37 | 14.19 | −8.51 | −2.97 | 57.37** | −13.61 | 6.45 | −8.39 |

| (28.73) | (41.83) | (15.06) | (30.34) | (28.87) | (18.27) | (9.73) | (18.71) | (26.07) | (11.35) | (7.14) | (9.20) | |

| Dec | 72.04** | −7.89 | −1.45 | 17.31 | 26.50 | 25.93 | −13.01 | −3.76 | 7.87 | −16.94 | 12.03* | −3.00 |

| (28.74) | (41.85) | (15.07) | (30.36) | (28.89) | (18.28) | (9.74) | (18.72) | (26.08) | (11.36) | (7.14) | (9.20) | |

| Constant | 181.03*** | 164.50*** | 154.46*** | 178.14*** | 67.31*** | 91.51*** | 82.18*** | 132.88*** | 80.50*** | 113.00*** | 69.53*** | 103.83*** |

| (22.22) | (32.36) | (11.65) | (23.48) | (22.34) | (14.13) | (7.53) | (14.48) | (20.17) | (8.78) | (5.52) | (7.12) | |

| R2 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.56 | 0.13 |

- Note: Number of observations is 96 for each beef cut. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Trend refers to a simple time trend. *, **, and ***, reflect significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels of significance, respectively.

We conducted tests of stationarity to determine whether any transformations were necessary to avoid potential spurious regression issues in our empirical analysis. We checked the stationarity of price premiums using unit root tests including the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) tests (Dickey & Fuller, 1981), Phillips-Perron tests (Phillips & Perron, 1988), and Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, Shin (KPSS) tests (Kwiatkowski et al., 1992). Stationarity test results, shown in the bottom panel of Table 1, support the conclusion that the annual changes in price premiums are largely stationary at the 5% level of significance.9

Table 3 describes the data sources and variable specifications. We measured the impact of changes in income on grass-fed beef premiums using the seasonally adjusted monthly real disposable personal income per capita published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis. These data were collected from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Food away from home (FAFH) and food at home (FAH) data were collected from USDA's Economics Research Service (USDA-ERS) and combined to derive the FAFH share of total food expenditures.10

| Variable | Abr. | Descriptions | Unit | Data source or calculations | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original forms | |||||||

| Income | INC | Real disposable personal income: per capita, monthly, seasonally adjusted annual rate | Chained | FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. | 43,944.67 | 43,419 | 2996.97 |

| 2012 | Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed. | ||||||

| Dollars | org/series/A229RX0 | ||||||

| FAFHS | FAFHS | Nominal monthly sales of food away from home, seasonally adjusted | $ million | US Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/dataproducts/food-expenditureseries/ | 64,185.50 | 63,572.84 | 8481.37 |

| FAHS | FAHS | Nominal monthly sales of food at home, seasonally adjusted | $ million | US Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/dataproducts/food-expenditureseries/ | 66,903.93 | 65,791.99 | 6469.15 |

| FAFH | FAFH | FAFH's share of food expenditure | % | 51.18 | 52.17 | 2.63 | |

| Climate change | CLIM | The number of published news on the US newspapers, with keywords climate change” or “greenhouse gas” or “global warming” and “cattle” | # | Access World News from NewsBank | 208.18 | 135.50 | 162.49 |

| Taste | TAS | The number of published news on the US newspapers, searched by keywords “taste” or “tasty” or “tender” or “juicy” or “flavor” or “savor” and “beef” | # | Access World News from NewsBank | 2615.98 | 2548.5 | 408.80 |

| Protein and minerals | PM | The number of published literatures, searched by key words “zinc” or “iron” or “protein” and “beef”. | # | PubMed | 29.41 | 28.00 | 9.98 |

| Fat | FAT | The number of published literatures, searched by key words “fat or cholesterol or heart disease or arteriosclerosis” and “diet” and “beef.” | # | PubMed | 7.36 | 7.00 | 3.12 |

| Revocation | REV | Dummy variable to indicate the revocation of “grass-fed” label in January 2016 (1 for January 2016 and the months after, 0 otherwise) | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.44 | ||

| COVID pandemic | COVID | Dummy variable to indicate the COVID-19 pandemic that started in March 2020 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.42 | ||

| Annual percentage differences | |||||||

| Income | D.LINC | Annual log-differences of real (in 2012 dollars) disposable personal income | 2.59 | 2.47 | 3.83 | ||

| FAFH | D.FAFH | Annual difference of FAFH's share of food expenditure | 0.59 | 0.75 | 4.04 | ||

| Climate change | D.LCLIM | Annual log-differences of CLIM | 20.87 | 16.81 | 64.48 | ||

| Taste | D.LTAS | Annual log-differences of TAS | 0.82 | 3.28 | 16.71 | ||

| Protein and minerals | D.LPM | Annual log-differences of PM | 6.16 | 6.55 | 26.76 | ||

| Fat | D.LFAT | Annual log-differences of FAT | −0.19 | 0.00 | 56.25 | ||

- Note: Abr. and SD represents abbreviation and standard deviation, respectively. Since the annual difference of FAFH (D.FAFH) represents the annual percentage change of food away from home, it is not necessary to take the logarithmic form of annually differenced FAFH.

Following the approach of Tonsor et al. (2018), we used media and medical information to measure the environmental concerns, beef taste, and nutritional information such as protein, minerals, and fat. Specifically, environmental information included news related to climate change and cattle. The taste consisted of the number of released articles regarding beef taste. Protein and minerals included the number of published literature on the topics of protein, zinc or iron in beef, respectively. Similarly, fat consisted of the number of published articles regarding fat in beef. The news releases associated with climate change and beef taste were collected from NewsBank. The published literature related to beef protein, minerals and beef fat was collected from PubMed. The monthly released news and published articles from 2014 to 2021 were collected by searching the articles with specific keywords listed in Table 3. These numbers of articles would represent the variables for climate change, beef taste, protein & minerals, as well as fat. However, we acknowledge that we cannot distinguish between positive or negative news using this approach.

Where possible, the independent variables entered Equation (6) in percentage change form. This facilitates easier interpretation of the model results in Equation (6). Descriptive statistics in Table 3 indicate that real disposable income increased by about 2.59% annually within our sample. With respect to news and information, the number of articles related to climate change increased by 20.87% annually, while the number of articles discussing fat decreased by 0.19% annually.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Columns (1)–(8) in Table 4 show the OLS estimation results of differential effects of the exogenous variables on premiums for specific cuts of grass-fed beef and Column (9) shows the results of a cut panel model that measured the average effects across cuts. In this table and the discussion that follows, we will focus our discussion on the cuts described by models that are overall significant. According to the low explanatory power indicated by the F-tests, we will omit the models for filet mignon, skirt steak, brisket, and chuck roast and focus our discussion on the remaining eight cuts.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation methods | OLS | FGLS-AR(1) | |||||||

| Beef cuts | Tenderloin | Ribeye steak | Sirloin steak | Flat iron steak | Flank steak | Rump roast | Short ribs | Stew meat | Cut-panel |

| Constant | 61.70** | 0.98 | 28.10 | −39.14*** | −9.79 | 34.75*** | 4.32 | 6.99 | 6.63 |

| (27.10) | (11.68) | (29.11) | (13.48) | (8.98) | (9.36) | (8.23) | (13.87) | (6.23) | |

| Income | −1.89 | 0.78 | 7.90*** | 1.12 | 0.46 | −3.31*** | 1.28*** | 0.83 | 0.12 |

| (1.91) | (0.87) | (1.54) | (1.34) | (0.70) | (0.80) | (0.34) | (0.65) | (0.42) | |

| FAFH | −5.67* | 1.15 | −6.22** | 2.51 | 0.26 | 1.42 | −0.68 | −1.02 | −0.98* |

| (2.90) | (1.04) | (2.55) | (1.83) | (0.73) | (1.05) | (0.53) | (0.68) | (0.57) | |

| Climate change | 0.65 | −0.01 | 0.32 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| (0.39) | (0.10) | (0.28) | (0.14) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.05) | (0.03) | |

| Taste | 0.21 | 0.84* | −0.62 | −0.67 | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.25 | 0.04 |

| (1.01) | (0.42) | (1.04) | (0.50) | (0.27) | (0.42) | (0.15) | (0.19) | (0.14) | |

| Protein and minerals | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.36** | 0.06 | 0.17* | 0.07 |

| (0.53) | (0.23) | (0.30) | (0.22) | (0.09) | (0.16) | (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.06) | |

| Fat | −0.33** | 0.02 | −0.21 | −0.17* | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| (0.17) | (0.10) | (0.15) | (0.09) | (0.04) | (0.08) | (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.03) | |

| Revocation | −29.48 | 19.74 | −1.77 | 58.74*** | 23.65* | −2.28 | −15.63 | −25.32* | 3.05 |

| (69.39) | (20.53) | (43.21) | (19.45) | (12.20) | (18.41) | (10.54) | (13.66) | (9.66) | |

| COVID | 52.44 | 8.59 | 23.09 | 5.29 | −16.97 | −4.07 | −7.70 | −22.46* | −2.59 |

| (74.44) | (26.27) | (41.95) | (34.21) | (12.08) | (21.24) | (7.93) | (11.89) | (10.94) | |

| Trend | −1.55 | −0.57 | −1.41 | −0.28 | −0.13 | −0.55 | 0.02 | 0.35 | −0.09 |

| (1.89) | (0.54) | (0.89) | (0.61) | (0.25) | (0.50) | (0.19) | (0.26) | (0.32) | |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.272 | 0.21 | 0.13 | |

| p value of F test | 0.01 | 0.06 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.10§ | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |

- Note: The dependent variables are annual differences of the respective price premiums, specified in Equation (9). Separate OLS models are estimated for each cut. Trend refers to a simple time trend. The number of observations for each individual cut is 84 and for the panel estimates is 1008. Robust standard errors are presented in parentheses. OLS estimates for meat cuts without overall significance (as determined by the F test) are not presented above. The p value of Wooldridge test for serial autocorrelation in the panel data is 0.0003. Hence, we reject the null hypothesis of no first order autocorrelation. FGLS-AR(1): pooled feasible GLS estimators with a heteroskedastic error structure with cross-sectional correlation and AR(1) autocorrelation structure. Cut-Panel is a beef panel including all the 12 cuts. See Table 3 for the descriptions for each independent variable. *, **, and ***, reflect significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels of significance, respectively. § denotes the actual p value that is smaller than 0.100.

A number of key tests were performed before estimating the cut panel. First, we used the panel structural break tests established by Ditzen et al. (2021). The novelty of their approach is that we are able to estimate and test for many known and unknown breaks in the panel data. Specifically, we conducted the hypothesis test of two unknown breaks during the sample period. We rejected the null of no breaks and hence the test detected two structural breaks in August 2016 and August 2017.11 With the break date known, we conducted the panel unit root tests developed by Karavias and Tzavalis (2014). This test permits structural breaks in panel data with known break dates. We rejected the null of unit roots and concluded that our data are panel stationary. We also checked the slope heterogeneity for the model using the tests established by Hashem Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) and Blomquist and Westerlund (2013). The results showed that all slope coefficients are identical across panels. In effect, this indicates that the effects of exogenous variables on grass-fed beef premiums are similar across the beef cuts. Thus, a pooled panel estimation would yield meaningful insights into our research question. In addition, serial correlation tests established by Drukker (2003) and Wooldridge (2010) suggested that the idiosyncratic errors have an autocorrelation structure. Therefore, we estimated Equation (6) using a pooled feasible GLS with an autocorrelation AR(1) process common to all the 12 beef cuts.

The OLS model results regarding the effect of income on the price premiums were mixed. In fact, only three cuts indicated a statistically significant relationship. A 1% growth in real annual disposable income increased the sirloin steak and short rib premiums by 7.90% and 1.28%, respectively, but decreased premiums for rump roasts by 3.31%. When pooled in the panel framework (Column 9), we observed that the overall effect of income on grass-fed beef premiums was positive, albeit not statistically significant.

Consumption of food away from home (FAFH) was the strongest negative driver of price premiums for grass-fed beef with significant effects observed for the panel specification and two individual beef cuts, tenderloin and sirloin steak. Tenderloin and sirloin steak appear to be the most sensitive to the increase in FAFH's share of the total food budget. Specifically, a 1% increase in FAFH resulted in a 5.67% and 6.22% decrease for tenderloin and sirloin steak premiums, respectively. The pooled panel results, on the other hand, revealed an average effect of −0.98% across all cuts following a 1% rise in FAFH. These results show that as the share of FAFH increased grass-fed beef premiums declined.

Increased media attention to climate change and cattle did not appear to affect grass-fed beef premiums. From the individual and pooled regressions, climate change information did not have significant effects on the premiums. On the other hand, media information about taste was positively associated with the grass-fed premium for ribeye steak. In particular, a 1% rise in media information on taste led to a 0.84% increase in price premiums for ribeye steak. The average effect across all cuts, however, was not statistically significant as per the pooled panel results.

The increase in articles related to nutritional information about protein and minerals had different effects on grass-fed beef premiums. Specifically, a 1% rise in articles associated with protein and mineral led to an increase of rump roast and stew meat premiums by 0.36 and 0.17%, respectively. On average, this effect was not significantly different from zero across all cuts.

Increased media information regarding fat had negative impacts on the grass-fed price premiums. Specifically, a 1% rise in media information on fat results in a fall in price premiums for tenderloin and flat iron steak by 0.33% and 0.17%, respectively. However, the average effect of increased media attention to fat on grass-fed premiums was not statistically significant.

The revocation of the grass-fed beef certification by USDA had a heterogeneous impact on the eight cuts estimated. In the case of a flat iron steak and flank steak, the revocation increased that cut's premium. Stew meat premium was negatively affected in the period following the discontinuation of this certification. When assessed in the pooled framework, the average effect was positive but not statistically significant. We attribute this to the fact that grass-fed labeling continues to be used by grocers and consumers may not be aware of the fact that this information is self-certified in most cases.

Lastly, our panel model showed that grass-fed stew meat premiums were roughly 22.46% lower during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the panel results suggested that the average grass-fed beef premiums have not changed significantly across all cuts during COVID-19. Our findings for the trend also indicated that annual changes in grass-fed premiums did not change significantly over time.

4.1 Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of our estimates using the raw price premiums as an alternative measure of price premiums. Table A2 in the appendix shows the estimation results. The F tests revealed that the regression for the flank steak was not statistically significant. Therefore, flank steak was omitted in Table A2. Since we did not detect structural breaks in the raw price premium series, we also used the Levin, Lin, and Chu panel unit root tests (Levin et al., 2002) to test for panel stationarity. We concluded that there was no unit root present in the series. The panel estimations did not display an autocorrelation structure in the idiosyncratic errors, but captured the panel heteroskedasticity, which indicated the raw price premiums varied by beef cuts. Therefore, the last column of Table A2 shows the estimates for the panel model using pooled feasible GLS estimators with panel-corrected standard errors (PGLS-PCSE) to adjust for heteroskedasticity across the panel.

While the magnitude of our coefficient estimates is different due to the differences in premium measurements applied, most of the OLS results in Table A2 are qualitatively similar to Table 4. For example, our estimates for the effects of income and food away from home on the relative price premiums (Table 4) are consistent with the effects on raw price premiums (Table A2) in terms of signs for individual cuts.

5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

This study examined price premiums for various cuts of grass-fed beef in the US retail markets over the period January 2014–December 2021. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine price premiums in grass-fed beef markets using observed market data rather than surveys or experiments.

Our results show that the observed premiums for grass-fed beef were heterogeneous across cuts. The highest premiums of 150%–193% were observed for premium stakes, specifically, sirloin, tenderloin, ribeye, and filet mignon. The lowest premiums of 48%–77% were observed for flank steak, skirt steak and short ribs. This evidence indicates that grass-fed beef premiums are not consistent with the price levels of various cuts, but rather driven by certain quality characteristics consumers are looking for and highlights the fact that grass-fed beef is more attractive for some cuts but not for others.

Since market data is not accompanied by quality characteristics, we attempted to measure them through general media attention to certain attributes, such as taste, protein, minerals, and fat. Our findings suggest that ribeye premiums were positively affected by information about taste, while rump roast and stew meat premiums were positively related to increased concerns and information flows regarding protein and minerals. While grass-fed beef is considered leaner and healthier (Cheung et al., 2017), these health benefits may result in negative taste implications, as less marbled beef usually appears to be less tender. Our findings show that increased information about fat decreased grass-fed premiums for tenderloin and flat iron steaks. However, our study did not find any significant impacts of information on fat on grass-fed premiums for other beef cuts. As the grass-fed beef industry continues to grow, these findings can be used to develop coefficient marketing strategies that would help motivate grass-fed beef consumption and enhance premiums. Specifically, increasing information about protein and minerals would enhance purchases of grass-fed rump roast and stew meat while promotion of grass-fed ribeye steaks should focus on their superior taste.

Since Tonsor et al. (2018) demonstrated that beef is not viewed as an environmentally friendly product, we attempted to assess whether the grass-fed production claim examined in this study appears to address consumer concerns about climate change and enhance the premiums they are willing to pay. However, we did not find any evidence that information about climate change is associated with changes in grass fed beef premiums.

According to our results, the biggest driver of grass-fed beef premiums in our sample was consumption of food away from home. In fact, as consumers increased their consumption of food away from home by 1%, the premiums accrued to grass-fed beef decreased by 0.98% on average. However, at the individual beef cut level, only tenderloin and sirloin steak were significantly affected by the consumption of food away from home. This finding is consistent with survey-based results in Umberger et al. (2002) study. Given the long-term trend of increasing consumption of food away from home highlighted in Saksena et al. (2018), this trend may lead to lower grass-fed beef premiums on average in the long run.

Consumption of food away from home also likely captured the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on grass-fed beef premiums. For example, in April of 2020, consumption of food away from home decreased by 16.2% from the previous year. This period was also associated with increase in premiums for ribeye steak, tenderloin, sirloin steak, brisket, short ribs, and stew meat by 0.05%, 1.11%, 90.64%, 149.36%, 8.35%, and 1.95%, respectively. At the same time an indicator variable for COVID-19 pandemic did not capture many additional effects, as it was only significant and negative for stew meat, but not in any other cases.

Changes in disposable income had a positive impact on premiums for grass-fed sirloin steak and short ribs, but not for other cuts. The lack of a significant positive link between income and grass-fed beef premiums in our panel results is not consistent with other studies (e.g., Li et al., 2016; Umberger et al., 2009) and may be a limitation resulting from our aggregated national-level data. Our measure of real income reflects general income trends in the US population, but it is not able to segment consumers in various income brackets to capture higher preferences for grass-fed beef among higher-income consumers. Furthermore, lack of the impact of the revocation of the grass-fed certification is likely associated with the fact that many consumers are not aware of this change as the program continues for small farms and the labeling continues to be observed at the grocery stores.

Although our models explain a relatively small proportion of annual variation in grass-fed beef premiums, our findings shed light on their relative magnitude and some of the main motivations behind grass-fed beef consumption. While we rely on indirect measures of consumer preferences as captured by media release information, it is important to recognize that our findings are largely consistent with survey-based conclusions of previous studies, as mentioned above. Confirming survey-based findings of previous studies with observed market data available from public sources is important and valuable, but it carries several limitations. We already mentioned that our aggregated national income data is unable to differentiate preferences for grass-fed beef across various income groups. Similarly, our aggregated national price data is unable to pick up any regional differences in price premiums in the niche markets that were highlighted in the previous literature (Badruddoza et al., 2022; Chang et al., 2010; Greene & McBride, 2015; Umberger et al., 2009). These limitations may be addressed by using disaggregated transaction-level data in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the editor, Prof. Monika Hartmann, three anonymous reviewers, and seminar participants at Virginia Tech University, North Carolina State University, and 2021 AAEA & WAEA Joint Annual Meeting, for helpful comments and suggestions. Wang acknowledges funding from the John Lee Pratt Animal Nutrition Program at Virginia Tech University.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX A:

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation methods | OLS | |||||||||||

| Beef Cuts | Filet mignon | Tenderloin | Ribeye steak | Sirloin steak | Skirt steak | Flat Iron steak | Flank steak | Rump roast | Brisket | Chuck roast | Short Ribs | Stew meat |

| Trend | −0.1448*** | −0.0711*** | −0.0025 | 0.0040 | 0.0402*** | 0.0452*** | 0.0165*** | 0.0078** | 0.0077 | 0.0076*** | −0.0216*** | −0.0024 |

| (0.0169) | (0.0195) | (0.0072) | (0.0079) | (0.0080) | (0.0067) | (0.0043) | (0.0038) | (0.0053) | (0.0024) | (0.0025) | (0.0030) | |

| Feb | 0.6536 | 5.0011* | 1.8900* | 0.9547 | −0.4939 | 0.5273 | 0.3185 | −0.0665 | 0.8510 | −0.7239** | 0.1978 | 0.1611 |

| (2.2772) | (2.6322) | (0.9638) | (1.0632) | (1.0794) | (0.8963) | (0.5821) | (0.5162) | (0.7178) | (0.3192) | (0.3434) | (0.4026) | |

| Mar | 1.0934 | 4.3159 | 1.2812 | 1.1495 | −0.2703 | 0.9771 | 0.2120 | −0.4431 | 1.6433** | −0.2115 | 0.4144 | −0.2277 |

| (2.2774) | (2.6324) | (0.9639) | (1.0633) | (1.0795) | (0.8964) | (0.5822) | (0.5162) | (0.7179) | (0.3192) | (0.3435) | (0.4026) | |

| Apr | 2.7269 | 2.5232 | 1.2030 | 0.9729 | −0.8893 | 0.3107 | −0.1170 | −0.0146 | 0.7081 | −0.2916 | 0.2110 | −0.0266 |

| (2.2777) | (2.6328) | (0.9640) | (1.0635) | (1.0796) | (0.8965) | (0.5822) | (0.5163) | (0.7180) | (0.3192) | (0.3435) | (0.4027) | |

| May | 3.2180 | 7.0181*** | 0.5042 | 1.4952 | −0.8782 | 1.6280* | −0.6197 | 0.4413 | 1.8979*** | 0.1058 | 0.2938 | −0.0005 |

| (2.2781) | (2.6333) | (0.9642) | (1.0637) | (1.0798) | (0.8967) | (0.5823) | (0.5164) | (0.7181) | (0.3193) | (0.3436) | (0.4028) | |

| Jun | 1.3590 | 7.7954*** | 0.2679 | 0.3074 | −0.7011 | 1.8615** | −0.7474 | −0.0952 | 1.9102*** | −0.2243 | 0.0892 | 0.1957 |

| (2.2787) | (2.6339) | (0.9644) | (1.0639) | (1.0801) | (0.8969) | (0.5825) | (0.5165) | (0.7183) | (0.3194) | (0.3437) | (0.4029) | |

| Jul | 3.0998 | 3.0427 | 1.3472 | 1.3659 | −0.8060 | 1.0288 | −0.8177 | −0.3205 | 1.1288 | −0.6082* | 0.2945 | −0.2295 |

| (2.2794) | (2.6347) | (0.9647) | (1.0643) | (1.0804) | (0.8972) | (0.5827) | (0.5167) | (0.7185) | (0.3195) | (0.3438) | (0.4030) | |

| Aug | 3.2011 | 3.0300 | 0.5753 | 1.3844 | −0.2512 | 0.4561 | −1.1017* | −0.4495 | 1.5048** | −0.4783 | 0.1823 | −0.0183 |

| (2.2802) | (2.6357) | (0.9651) | (1.0646) | (1.0808) | (0.8975) | (0.5829) | (0.5168) | (0.7188) | (0.3196) | (0.3439) | (0.4031) | |

| Sep | 1.6347 | 2.4249 | 0.3952 | 1.0678 | −0.3551 | −0.0903 | −0.3381 | −0.0448 | 0.4809 | −0.1309 | −0.2386 | −0.1722 |

| (2.2811) | (2.6367) | (0.9655) | (1.0651) | (1.0812) | (0.8979) | (0.5831) | (0.5171) | (0.7191) | (0.3197) | (0.3440) | (0.4033) | |

| Oct | 1.5732 | 4.8897* | 1.0627 | 0.9026 | −0.7715 | −0.3580 | −0.3809 | 0.3886 | 1.2232* | −0.0160 | −0.1133 | −0.2848 |

| (2.2822) | (2.6380) | (0.9659) | (1.0656) | (1.0817) | (0.8983) | (0.5834) | (0.5173) | (0.7194) | (0.3199) | (0.3442) | (0.4035) | |

| Nov | 2.1670 | 1.9203 | 1.2634 | 0.8270 | −0.6672 | 0.5143 | −0.5531 | 0.1149 | 1.5237** | −0.2581 | 0.2398 | −0.2414 |

| (2.2834) | (2.6394) | (0.9664) | (1.0661) | (1.0823) | (0.8988) | (0.5837) | (0.5176) | (0.7198) | (0.3200) | (0.3444) | (0.4037) | |

| Dec | 7.4041*** | 0.3783 | 0.6961 | 1.3925 | 0.8704 | 0.5557 | −0.5336 | 0.0836 | 0.3820 | −0.3332 | 0.6124* | −0.0033 |

| (2.2847) | (2.6409) | (0.9670) | (1.0667) | (1.0829) | (0.8993) | (0.5840) | (0.5179) | (0.7202) | (0.3202) | (0.3446) | (0.4039) | |

| Constant | 24.5353*** | 17.4938*** | 12.5705*** | 9.4446*** | 3.6515*** | 5.9827*** | 5.6236*** | 4.9576*** | 3.4826*** | 4.4441*** | 3.3342*** | 4.7174*** |

| (1.7666) | (2.0421) | (0.7477) | (0.8249) | (0.8374) | (0.6954) | (0.4516) | (0.4004) | (0.5569) | (0.2476) | (0.2664) | (0.3123) | |

| R2 | 0.5048 | 0.2801 | 0.0810 | 0.0493 | 0.2710 | 0.4106 | 0.2291 | 0.1173 | 0.1849 | 0.2224 | 0.4974 | 0.0486 |

- Note: Number of observations is 96 for each beef cut. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Trend refers to a simple time trend. *, **, and ***, reflect significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels of significance, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation methods | OLS | PGLS-PCSE | ||||||||||

| Beef cuts | Filet mignon | Tenderloin | Ribeye steak | Sirloin steak | Skirt steak | Flat iron steak | Rump roast | Brisket | Chuck roast | Short ribs | Stew meat | Cut-panel |

| Constant | 3.7775** | 4.2580** | 0.5204 | 1.9907 | 0.0819 | −2.2109*** | 1.2768*** | 0.6671 | 0.6340*** | 0.2511 | 0.5995 | 0.9846*** |

| (1.4730) | (2.0377) | (0.7841) | (1.2492) | (0.9579) | (0.6643) | (0.2722) | (0.6708) | (0.1929) | (0.3385) | (0.5654) | (0.3450) | |

| Income | −0.0002 | −0.0004 | 0.0002** | 0.0005*** | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | −0.0002*** | 0.0000 | −0.0000 | 0.0001*** | 0.0001** | 0.0000 |

| (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0001) | |

| FAFH | −0.0529 | −0.3994* | 0.1458** | −0.1473* | −0.0475 | 0.3210*** | 0.0423 | −0.0226 | 0.0267 | −0.0026 | −0.0247 | −0.0107 |

| (0.1812) | (0.2061) | (0.0659) | (0.0815) | (0.0857) | (0.0872) | (0.0344) | (0.0694) | (0.0242) | (0.0315) | (0.0259) | (0.0386) | |

| Climate change | 0.0116* | 0.0163* | 0.0001 | −0.0017 | 0.0015 | −0.0062** | −0.0029** | 0.0010 | −0.0020* | −0.0005 | −0.0009 | 0.0012 |

| (0.0067) | (0.0088) | (0.0027) | (0.0032) | (0.0026) | (0.0028) | (0.0011) | (0.0020) | (0.0010) | (0.0009) | (0.0008) | (0.0012) | |

| Taste | −0.0027 | 0.0028 | 0.0023** | 0.0009 | −0.0015 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0014 | −0.0001 | 0.0002 | −0.0001 | 0.0003 |

| (0.0023) | (0.0030) | (0.0011) | (0.0012) | (0.0009) | (0.0009) | (0.0005) | (0.0011) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0003) | (0.0004) | |

| Protein and minerals | 0.0293 | 0.0680 | 0.0105 | −0.0008 | −0.0340 | 0.0169 | 0.0326** | −0.0093 | 0.0152 | 0.0147 | 0.0222 | 0.0110 |

| (0.0723) | (0.1092) | (0.0538) | (0.0391) | (0.0348) | (0.0407) | (0.0138) | (0.0330) | (0.0112) | (0.0117) | (0.0145) | (0.0153) | |

| Fat | −0.0579 | 0.0278 | −0.0310 | −0.1059 | −0.0337 | -0.0829 | 0.0427 | −0.0823* | 0.0024 | −0.0325 | −0.0213 | −0.0305 |

| (0.1273) | (0.2388) | (0.1140) | (0.0912) | (0.0679) | (0.0787) | (0.0311) | (0.0482) | (0.0227) | (0.0275) | (0.0378) | (0.0309) | |

| Revocation | −4.1044 | −4.4490 | −0.1722 | −3.5030** | 3.2990* | 3.2014*** | −0.7240 | 1.4620 | −0.6319** | −1.0348** | −1.8244*** | −0.6410 |

| (2.8169) | (3.5822) | (1.3932) | (1.4190) | (1.6746) | (0.9932) | (0.5402) | (1.1753) | (0.3158) | (0.4394) | (0.5773) | (0.4969) | |

| COVID | 0.2750 | 0.8532 | 1.6545 | −0.6933 | 0.2428 | 1.5941 | 0.2065 | 3.8857*** | −0.2638 | −0.6778* | −0.9859* | 0.4409 |

| (3.2782) | (3.5908) | (1.5556) | (1.2462) | (1.5137) | (1.7150) | (0.5575) | (1.3989) | (0.4442) | (0.3809) | (0.5140) | (0.6011) | |

| Trend | −0.0466 | −0.0396 | −0.0252 | 0.0191 | −0.0622* | −0.0127 | −0.0076 | −0.0667** | 0.0035 | 0.0090 | 0.0263** | −0.0174 |

| (0.0680) | (0.0803) | (0.0329) | (0.0262) | (0.0360) | (0.0329) | (0.0140) | (0.0295) | (0.0086) | (0.0092) | (0.0124) | (0.0121) | |

| R2 | 0.1212 | 0.2185 | 0.1292 | 0.3317 | 0.1773 | 0.2758 | 0.2694 | 0.1640 | 0.1627 | 0.2826 | 0.2259 | |

| p value of F test | 0.0202 | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | <0.0001 | 0.0411 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0524 | 0.0011 | 0.0047 | 0.0001 | |

- Note: The number of observations for each individual cut is 84 and for panel estimates is 1008. Robust standard errors are presented in parentheses. The dependent variables are annual difference of raw price premiums. Trend refers to a simple time trend. Independent variables are as specified in Table 3. PGLS-PCSE: Pooled feasible GLS estimates with panel-corrected standard error. Cut-Panel is a beef panel including all 12 cuts. *, **, and ***, reflect significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels of significance, respectively.

Biographies

Yangchuan Wang is a former PhD student in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at Virginia Tech. His research fields during his PhD studies are price analysis, agricultural economics and environmental economics. His research agenda explore the pattern of grass-fed beef price premiums and the impact of animal diseases on the US meat demand. He also works on various topics of US livestock futures prices as well as air pollution in developing countries.

Olga Isengildina-Massa is a professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at Virginia Tech. Her research program examines commodity market price dynamics, evaluates forecasting performance of USDA and private firms, develops innovative forecasting approaches, and proposes effective price risk management strategies in order to increase profitability and income stability for agribusiness firms. She uses innovative teaching methods in her classes and though the experimental learning program Commodity Investing by Students (COINS), which enables students to gain hands-on experience in trading and investing in commodity markets.

Shamar Stewart is an assistant professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at Virginia Tech. His research interests intersect the areas of commodity prices and volatility forecasting and the impact of structural shocks on economic and financial variables. The common thread across his research topics is the use of non-linear time series and forecasting methods to offer policy-relevant solutions. Bridging the connection between research and classroom instruction, Shamar also serves as a faculty advisor for the student-managed investment fund program, Commodity Investing by Students (COINS) at VT.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1 Grain finished beef ready for sale weighs between 1200 and 1400 pounds. At this weight, the cattle are between 15 and 22 months old. Grass-finished beef, on the other hand, when ready for sale weighs between 1000 and 1200 pounds. At this weight, the cattle are between 20 and 26 months old (Harvest Returns, 2018).

- 2 The reader is directed to Table 3 for a more detailed explanation of these media-related variables.

- 3 The standards for the claims: see details at https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/auditing/grass-fed-SVS

- 4 https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html

- 5 The annual difference form of price premiums can get rid of the problem of seasonality and unit roots in price premiums. The reader is directed to Data section for the findings of seasonality and unit roots in relative price premiums and the specifications of annual difference of the relative price premium.

- 6 Ribeye roast, bottom round roast, tri-tip, and sirloin roast had multiple missing values and thus were excluded from the estimation. Of the remaining 12 cuts, less than 2.4% (28 data points) were missing and would be useful for further inference. To preserve potential seasonality in the raw data, missing values were imputed using the relevant monthly averages over the sample period.

- 7 This pattern is likely caused by instances of steak thefts at supermarkets and cattle rustling in 2016 (Tuttle, 2016).

- 8 The equivalent results for the grass-fed premiums, measured as raw price premiums, are presented in Table A1 of the appendix section.

- 9 Before conducting the seasonal differencing, we conducted a unit root test of the premium as defined in equation (2). Save for sirloin steak and stew meat, the ADF tests failed to reject the null hypothesis of unit root. The KPSS tests failed to reject the null of stationary in all but three cuts (filet mignon, flat iron steak, and short ribs).

- 10 The data on FAFH sales and FAH sales are based on final-purchase estimates. FAFH sales included full-service restaurants, retail stores, schools and colleges, and so on. Purchases from food stores, warehouse clubs, and home production were counted as FAH sales. See details at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-expenditureseries/documentation/revisions.

- 11 We also conducted the hypothesis test of 1 unknown break as the null versus 2 unknown breaks as the alternative. We rejected the null of 1 break.