Risk factors for suicide in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A population-based study

Chao Wang, Haoda Chen, and Yuanchi Weng contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Background

Patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) face a notable risk of suicide. However, comprehensive population-based studies on suicide risk in PDAC patients have been lacking. This study seeks to explore the suicide risk in PDAC patients and identify the specific risk factors associated with suicide-related mortality.

Methods

A cohort of 101,382 PDAC patients was extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, spanning from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2017. The study employed the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) to assess the relative risk of suicide in PDAC patients compared to the general US population. The Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Fine and Grey method were utilized to pinpoint the risk factors linked to suicide-specific mortality.

Results

PDAC patients exhibited a 3.51-fold higher risk of suicide compared to the general US population. This risk demonstrated an upward trend over the years. Notably, individuals aged 70–74 years faced a significantly elevated risk of suicide (SMR = 5.14, 95% CI: 3.10–8.03). Furthermore, there were distinct peaks in suicide risk at 1–4- and 25–28-month post-diagnoses (SMR = 15.04 and 2.72, respectively). Factors, such as gender, chemotherapy status, and marital status, emerged as significant independent predictors of suicide-specific mortality in PDAC patients.

Conclusions

This study highlights a heightened suicide risk among PDAC patients in comparison to the general US population. It underscores the crucial need for continuous monitoring of the psychological well-being of all PDAC patients. Additionally, considering the elevated risk, the application of antidepressant therapy could be beneficial for those identified as having a higher risk of suicide.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the average life expectancy of cancer patients increases, noncancer-related causes of death are becoming more prevalent.1 Among these, suicide has emerged as a significant threat to the well-being and lives of cancer patients.2 Globally, over 800,000 individuals succumb to suicide annually, accounting for 1.49% of total global mortality.3, 4

The diagnosis of cancer often exerts a profound emotional toll on patients. This can lead to various mental health disorders, including anxiety, depression, and heightened stress levels, all of which may increase the risk of suicidal tendencies.5 Extensive research consistently shows that individuals with cancer face notably higher suicide rates compared to the general population.6-8 A comprehensive meta-analysis, comprising 28 studies and involving 46,952,813 patients, revealed that the suicide rate among cancer patients was nearly double that of the general populace SMR (standardized mortality ratio = 1.85).3 Furthermore, a population-based study conducted by Katherine et al. in England, covering patients diagnosed with cancer between 1995 and 2015, found a 20% elevated risk of suicide among cancer patients.9 Remarkably, this study also demonstrated that individuals diagnosed with pancreatic cancer had the second-highest suicide rate among all cancer types, with a 3.89-fold greater risk compared to the general population. Given these compelling findings, it is imperative to pay special attention to the suicide risk among patients specifically diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). However, to date, there has been no comprehensive analysis examining the relationship between PDAC and suicide. Hence, we utilized data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to conduct a large-scale, population-based analysis. The primary objective of our study was to discern the risk factors for suicide among PDAC patients compared to the general population.

2 METHODS

2.1 Database and study population

The information regarding patients diagnosed with PDAC was sourced from the SEER database for our study. The SEER database is backed by the Surveillance Research Program (SRP) within the National Cancer Institute and represents 28% of the entire US population. We utilized data from the SEER 18 registries, spanning from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2017, specifically focusing on entries that included treatment information. The primary site of tumors was confined to the pancreas (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition [ICD-O-3], topographic code C25.0, C25.1, C25.2, 25.3, 25.7, 25.8, 25.9). Additionally, we narrowed down the histology to adenocarcinoma in accordance with the ICD-O-3 morphologic codes (8140/3: adenocarcinoma and 8500/3: infiltrating duct carcinoma). Only patients with confirmed positive histology were included, whereas those diagnosed through autopsy or death certificate were excluded from our study.

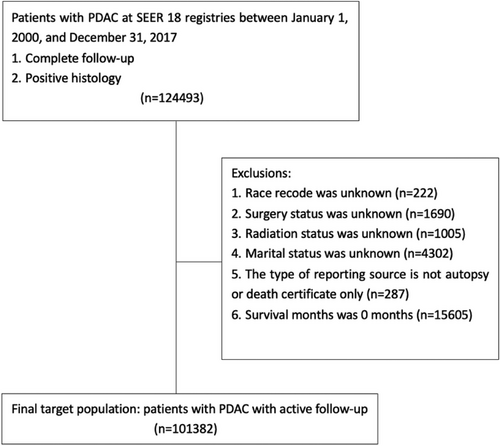

The demographic profile of PDAC patients encompassed age, year of diagnosis, sex, and race. The SEER database also provided tumor-specific details, including primary site, differentiation grade, and SEER-combined tumor stage. Treatment-related data covered surgical status, chemotherapy records, and radiotherapy records. Marital status was categorized as “married,” “single (never married),” “divorced,” “widowed,” or “separated.” To prevent statistical bias, insurance status was omitted from our study as patients aged ≥65 years typically received benefits from Medicare insurance. Patients with incomplete or uncertain data on the mentioned variables were excluded from the analysis. Cases where the cause of death was recorded as “Suicide and Self-inflicted Injury (50,220)” were considered instances of suicide. Ultimately, our study included a total of 101,382 patients (Figure 1).

2.2 Statistical analysis

We employed the SMR to evaluate the risk of suicide in patients with PDAC across various subgroups. SMRs were derived as the ratios of observed deaths to expected deaths within standardized groups. Survival time was defined as the duration from the initial PDAC diagnosis to the last follow-up or the time of passing. Our study considered both cancer-specific and suicide-specific survival as endpoints. To scrutinize the impact of different variables on the survival of PDAC patients, we conducted univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Subsequently, the log-rank test was utilized to confirm the statistical distinctions among each subgroup. Given that alternative causes of death represented competing risk data, we employed the Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Fine and Grey method to evaluate suicide risk among different subgroups. The computation of SMRs was performed using R software for Windows version 4.2.1. All other analyses were carried out using Stata (Stata Corporation, version 15.1). For all tests, a two-sided approach was adopted, with p-values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Baseline characteristics

Our study included a total of 101,382 patients diagnosed with PDAC, sourced from the SEER database. Among these patients, 6016 ultimately survived. Of the entire cohort, 85,055 (83.90%) succumbed to PDAC, 88 (0.09%) to suicide, and 10,223 (10.09%) to other causes. Males comprised 51.14% of the study population and accounted for 92.05% of individuals who died by suicide. Table 1 shows all demographic and clinicopathologic features in detail.

| Suicides | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of patients, n (%) | No. of patients, n (%) | Expected deaths | SMR (95%CI) |

| All | 101,382 | 88 | 25.08 | 3.51 (2.81–4.32) |

| Age | ||||

| <65 years | 37,387 (36.88%) | 26 (29.55%) | 11.35 | 2.29 (1.50–3.36) |

| ≥65 years | 63,995 (63.12%) | 62 (70.45%) | 15.25 | 4.06 (3.12–5.21) |

| Year at diagnosis | ||||

| 2000–2005 | 25,445 (15.10%) | 19 (21.59%) | 5.95 | 3.20 (1.92–4.99) |

| 2006–2011 | 33,729 (33.27%) | 25 (28.41%) | 8.80 | 2.84 (1.84–4.20) |

| 2012–2017 | 42,208 (41.63%) | 44 (50.00%) | 11.90 | 3.70 (2.69–4.97) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 51,836 (51.13%) | 81 (92.05%) | 22.23 | 3.64 (2.90–4.53) |

| Female | 49,546 (48.87%) | 7 (7.95%) | 4.41 | 1.59 (0.64–3.28) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 81,602 (80.49%) | 78 (88.64%) | 21.93 | 3.56 (2.81–4.44) |

| Black | 12,053 (11.89%) | 5 (5.68%) | 2.73 | 1.84 (0.60–4.28) |

| Other | 7727 (7.62%) | 5 (5.68%) | 1.98 | 2.53 (0.82–5.90) |

| Primary site | ||||

| Head of pancreas | 54,799 (54.05%) | 49 (55.68%) | 15.73 | 3.12 (2.31–4.12) |

| Body of pancreas | 12,615 (12.44%) | 13 (14.77%) | 3.13 | 4.16 (2.22–7.12) |

| Tail of pancreas | 12,031 (11.87%) | 10 (11.36%) | 2.91 | 3.44 (1.66–6.34) |

| Pancreatic duct | 631 (0.62%) | 0 | / | / |

| Other specified parts of pancreas | 1514 (1.49%) | 2 (2.27%) | 0.41 | 4.88 (0.62–18.37) |

| Overlapping lesion of pancreas | 7511 (7.41%) | 5 (5.68%) | 1.81 | 2.76 (0.91–6.53) |

| Pancreas, NOS | 12,281 (12.11%) | 9 (10.23%) | 2.48 | 3.63 (1.66–6.88) |

| Grade | ||||

| Well differentiated; grade I | 4433 (4.37%) | 3 (3.41%) | 1.58 | 1.91 (0.39–5.58) |

| Moderately differentiated; grade II | 17,915 (17.67%) | 22 (25.00%) | 5.98 | 3.68 (2.31–5.58) |

| Poorly differentiated; grade III | 15,764 (15.55%) | 7 (7.95%) | 4.40 | 1.59 (0.64–3.28) |

| Undifferentiated; anaplastic; grade IV | 593 (0.58%) | 0 | / | / |

| Unknown | 62,677 (61.82%) | 56 (63.64%) | 14.53 | 3.85 (2.91–5.01) |

| SEER stage | ||||

| Localized | 8365 (8.25%) | 8 (9.09%) | 2.75 | 2.91 (3.14–14.33) |

| Regional | 37,662 (37.15%) | 34 (38.64%) | 12.58 | 2.70 (1.87–3.78) |

| Distant | 51,825 (51.12%) | 43 (48.86%) | 10.43 | 4.12 (2.99–5.56) |

| Unknown | 3530 (3.48%) | 3 (3.41%) | 0.87 | 3.44 (0.71–10.06) |

| Surgery | ||||

| Partial pancreatectomy, NOS | 2722 (2.68%) | 3 (3.41%) | 1.10 | 2.72 (0.56–7.94) |

| Local or partial pancreatectomy and duodenectomy | 14,825 (14.62%) | 9 (10.23%) | 6.20 | 1.45 (0.66–2.76) |

| Total pancreatectomy | 2325 (2.29%) | 1 (1.14%) | 0.95 | 1.05 (0.03–5.82) |

| Extended pancreatoduodenectomy | 937 (0.92%) | 1 (1.14%) | 0.38 | 2.60 (0.06–14.50) |

| Surgery, NOS | 567 (0.56%) | 1 (1.14%) | 0.19 | 5.33 (0.34–74.29) |

| Surgery not performed | 80,006 (78.92%) | 73 (82.95%) | 17.79 | 4.10 (3.22–5.16) |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 60,932 (60.10%) | 43 (48.86%) | 18.94 | 2.27 (1.62–3.02) |

| No/unknown | 40,450 (39.90%) | 45 (51.14%) | 7.47 | 6.03 (4.40–8.06) |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 20,278 (20.00%) | 15 (17.05%) | 7.32 | 2.05 (1.14–3.38) |

| No/Unknown | 81,104 (80.00%) | 73 (82.95%) | 19.31 | 3.78 (2.97–4.76) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 60,444 (59.62%) | 53 (60.23%) | 18.68 | 2.84 (2.12–3.71) |

| Single | 12,895 (12.72%) | 12 (13.64%) | 3.23 | 3.72 (1.92–6.51) |

| Divorced | 10,157 (10.02%) | 15 (17.04%) | 2.23 | 6.74 (3.77–11.12) |

| Widowed | 16,874 (16.64%) | 8 (9.09%) | 2.25 | 3.56 (1.54–7.01) |

| Separated | 1012 (1.00%) | 0 | / | / |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; NOS, not otherwise specified; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

3.2 Standardized mortality ratio of each subgroup

The suicide rate among patients with PDAC stood at 42.75 per 100,000 person-years. Notably, individuals with PDAC faced a 3.51-fold higher risk of suicide compared to the general US population with comparable age, sex, and race distributions (95% CI: 2.81–4.32). A detailed breakdown of the SMR for patients with PDAC across different subgroups can be found in Table 1. It reveals that each subgroup of patients exhibited an elevated suicide ratio when compared to the broader US population.

3.3 The Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Fine and Grey method for suicide-specific mortality in patients with PDAC

As shown in Table 2, when focusing on suicide-specific mortality as the endpoint, a significantly higher risk was observed in males compared to females hazard ratio (HR: 12.193, 95% CI: 5.465–27.201, p < 0.001). Furthermore, patients who did not receive chemotherapy faced a 65.0% increased risk of suicide-specific mortality compared to those who did (HR: 1.650, 95% CI: 1.054–2.584, p = 0.029). Additionally, a divorced status was found to be independently associated with an increased risk of suicide-specific mortality in patients with PDAC, showing a 133.3% higher risk (HR: 2.333, 95% CI: 1.299–4.192, p = 0.005). Notably, no significant differences were observed in terms of age, year of diagnosis, race, primary tumor site, tumor differentiation grade, SEER-combined tumor stage, surgery status, or radiotherapy status.

| Variables | Nelson–Aalen analysis | Fine and Grey model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | SE | p | HR (95% CI) | SE | p | |

| Age, reference(<65 years) | ||||||

| ≥65 years | 1.392 (0.881–2.200) | 0.325 | 0.157 | 1.470 (0.888–2.432) | 0.378 | 0.134 |

| Year at diagnosis, reference (2000–2005) | ||||||

| 2006–2011 | 0.993 (0.547–1.801) | 0.302 | 0.981 | 1.021 (0.563–1.851) | 0.310 | 0.945 |

| 2012–2017 | 1.412 (0.826–2.415) | 0.386 | 0.207 | 1.442 (0.842–2.470) | 0.396 | 0.183 |

| Sex, reference (female) | ||||||

| Male | 11.102 (5.131–24.023) | 4.372 | <0.001 | 12.193 (5.465–27.201) | 4.992 | <0.001 |

| Race, reference (white) | ||||||

| Black | 0.443 (0.180–1.095) | 0.204 | 0.078 | 0.443 (0.177–1.111) | 0.208 | 0.083 |

| Other | 0.683 (0.277–1.688) | 0.315 | 0.409 | 0.793 (0.322–1.948) | 0.364 | 0.613 |

| Primary site, reference (head of pancreas) | ||||||

| Body of pancreas | 1.155 (0.627–2.129) | 0.360 | 0.643 | 1.126 (0.585–2.166) | 0.376 | 0.722 |

| Tail of pancreas | 0.945 (0.479–1.865) | 0.328 | 0.870 | 0.836 (0.412–1.697) | 0.302 | 0.620 |

| Pancreatic duct | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Other specified parts of pancreas | 1.482 (0.360–6.093) | 1.069 | 0.586 | 1.420 (0.346–5.837) | 1.024 | 0.627 |

| Overlapping lesion of pancreas | 0.748 (0.298–1.878) | 0.351 | 0.537 | 0.717 (0.278–1.848) | 0.346 | 0.491 |

| Pancreas, NOS | 0.873 (0.429–1.777) | 0.317 | 0.708 | 0.764 (0.364–1.601) | 0.288 | 0.476 |

| Grade, reference (well differentiated; grade I) | ||||||

| Moderately differentiated; grade II | 1.827 (0.547–6.104) | 1.124 | 0.327 | 1.928 (0.575–6.461) | 1.190 | 0.287 |

| Poorly differentiated; grade III | 0.671 (0.174–2.596) | 0.463 | 0.564 | 0.629 (0.164–2.418) | 0.432 | 0.500 |

| Undifferentiated; anaplastic; grade IV | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Unknown | 1.377 (0.431–4.395) | 0.815 | 0.589 | 1.051 (0.323–3.414) | 0.632 | 0.935 |

| SEER stage, reference (localized) | ||||||

| Regional | 0.933 (0.432–2.015) | 0.367 | 0.859 | 1.106 (0.490–2.499) | 0.460 | 0.808 |

| Distant | 0.895 (0.421–1.900) | 0.343 | 0.772 | 0.892 (0.402–1.976) | 0.362 | 0.777 |

| Unknown | 0.908 (0.241–3.422) | 0.615 | 0.887 | 0.891 (0.234–3.399) | 0.609 | 0.866 |

| Surgery, reference (partial pancreatectomy, NOS) | ||||||

| Local or partial pancreatectomy and duodenectomy | 0.549 (0.149–2.028) | 0.366 | 0.368 | 0.511 (0.136–1.925) | 0.346 | 0.321 |

| Total pancreatectomy | 0.389 (0.040–3.737) | 0.449 | 0.413 | 0.376 (0.039–3.576) | 0.432 | 0.394 |

| Extended pancreatoduodenectomy | 0.963 (0.100–9.266) | 1.112 | 0.974 | 0.934 (0.098–8.933) | 1.076 | 0.953 |

| Surgery, NOS | 1.589 (0.165–15.270) | 1.835 | 0.688 | 1.826 (0.171–19.524) | 2.208 | 0.618 |

| Surgery not performed | 0.826 (0.260–2.622) | 0.487 | 0.746 | 1.011 (0.301–3.398) | 0.625 | 0.986 |

| Chemotherapy, reference (yes) | ||||||

| No/unknown | 1.666 (1.098–2.527) | 0.354 | 0.016 | 1.650 (1.054–2.584) | 0.377 | 0.029 |

| Radiotherapy, reference (yes) | ||||||

| No/Unknown | 1.277 (0.734–2.220) | 0.360 | 0.387 | 1.015 (0.598–1.722) | 0.274 | 0.956 |

| Marital status, reference (married) | ||||||

| Single | 1.078 (0.576–2.017) | 0.344 | 0.814 | 1.298 (0.669–2.518) | 0.439 | 0.441 |

| Divorced | 1.701 (0.959–3.017) | 0.497 | 0.069 | 2.333 (1.299–4.192) | 0.698 | 0.005 |

| Widowed | 0.554 (0.263–1.164) | 0.210 | 0.119 | 1.034 (0.471–2.270) | 0.415 | 0.934 |

| Separated | 1.096 (1.023–1.174) | 0.039 | 0.009 | / | / | / |

- Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

3.4 Standardized mortality ratio of PDAC patients stratified by age at diagnosis

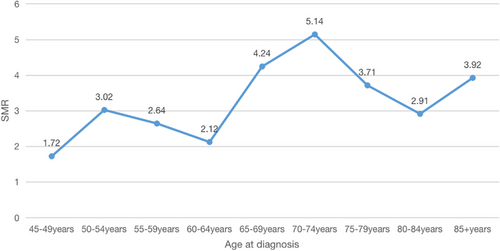

Table 3 provides the SMR for patients with PDAC across different age groups. Notably, patients diagnosed between the ages of 70 and 74 years exhibited the highest risk of suicide. This trend is represented in Figure 2, where a conspicuous peak is evident in this same age bracket, confirming an SMR of 5.14 (95% CI: 3.10–8.03). The Kruskal–Wallis rank test and trend test were employed to scrutinize the baseline characteristics of the patients included in this study. Furthermore, we conducted an analysis to investigate the interaction between the age group and all the variables considered. The results revealed that patients between 70 and 74 years of age presented with more advanced tumor stages (p = 0.034, Table 4).

| Patients with PDAC | General population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (years) | Observed deaths, n (%) | Mortality ratea | SMR (95%CI) | Expected deaths | Mortality ratea |

| 45–49 | 2 (2.27) | 30.89 | 1.72 (0.21–6.22) | 1.16 | 17.96 |

| 50–54 | 7 (7.95) | 55.72 | 3.02 (1.21–6.22) | 2.33 | 18.45 |

| 55–59 | 9 (10.23) | 46.15 | 2.64 (1.21–5.01) | 3.41 | 17.48 |

| 60–64 | 8 (9.09) | 31.93 | 2.12 (0.92–4.19) | 3.78 | 15.06 |

| 65–69 | 16 (18.18) | 57.69 | 4.24 (2.42–6.89) | 3.77 | 13.61 |

| 70–74 | 19 (21.59) | 73.62 | 5.14 (3.10–8.03) | 3.70 | 14.32 |

| 75–79 | 13 (14.77) | 59.62 | 3.71 (1.97–6.33) | 3.51 | 16.07 |

| 80–84 | 8 (7.95) | 52.47 | 2.91 (1.17–5.99) | 2.75 | 18.03 |

| 85+ | 6 (7.95) | 71.19 | 3.92 (2.15–10.98) | 1.53 | 18.16 |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

- a Per 100,000 person-years.

| Characteristics | 70–74 years (n = 15,733) | Other patients (n = 85,649) | P | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year at diagnosis | 0.148 | 0.390 | ||

| 2000–2005 | 4176 (26.54%) | 21,269 (24.83%) | ||

| 2006–2011 | 4959 (31.52%) | 28,770 (33.59%) | ||

| 2012–2017 | 6598 (41.94%) | 35,610 (41.58%) | ||

| Sex (male) | 8013 (50.93%) | 43,823 (51.66%) | 0.592 | 0.266 |

| Race | <0.001 | 0.139 | ||

| White | 12,873 (81.82%) | 68,729 (80.24%) | ||

| Black | 1656 (10.53%) | 10,397 (12.14%) | ||

| Other | 1204 (7.65%) | 6523 (7.62%) | ||

| Primary site | 0.128 | 0.508 | ||

| Head of pancreas | 8584 (54.56%) | 46,215 (53.96%) | ||

| Body of pancreas | 1934 (12.29%) | 10,681 (12.47%) | ||

| Tail of pancreas | 1857 (11.80%) | 10,174 (11.88%) | ||

| Pancreatic duct | 96 (0.61%) | 535 (0.62%) | ||

| Other specified parts of pancreas | 236 (1.50%) | 1278 (1.49%) | ||

| Overlapping lesion of pancreas | 1193 (7.58%) | 6318 (7.38%) | ||

| Pancreas, NOS | 1833 (11.65%) | 10,448 (12.20%) | ||

| Grade | <0.001 | 0.324 | ||

| Well differentiated; grade I | 747 (4.75%) | 3686 (4.30%) | ||

| Moderately differentiated; grade II | 2944 (18.71%) | 14,971 (17.48%) | ||

| Poorly differentiated; grade III | 2538 (16.13%) | 13,226 (15.44%) | ||

| Undifferentiated; anaplastic; grade IV | 90 (0.57%) | 503 (0.59%) | ||

| Unknown | 9414 (59.84%) | 53,263 (62.19%) | ||

| SEER stage | 0.079 | 0.034 | ||

| Localized | 1192 (7.58%) | 6173 (7.21%) | ||

| Regional | 6081 (38.65%) | 31,581 (36.87%) | ||

| Distant | 7984 (50.75%) | 44,841 (52.35%) | ||

| Unknown | 476 (3.02%) | 3054 (3.57%) | ||

| Surgery | <0.001 | 0.450 | ||

| Partial pancreatectomy, NOS | 463 (2.94%) | 2259 (2.64%) | ||

| Local or partial pancreatectomy and duodenectomy | 2516 (15.99%) | 12,309 (14.37%) | ||

| Total pancreatectomy | 392 (2.49%) | 1933 (2.26%) | ||

| Extended pancreatoduodenectomy | 155 (0.99%) | 782 (0.91%) | ||

| Surgery, NOS | 88 (0.56%) | 479 (0.56%) | ||

| Surgery not performed | 12,119 (77.03%) | 67,887 (79.26%) | ||

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 9709 (61.71%) | 51,223 (59.81%) | <0.001 | 0.618 |

| Radiotherapy (yes) | 3169 (20.14%) | 17,109 (19.98%) | 0.652 | 0.310 |

| Marital status | <0.001 | 0.169 | ||

| Married | 9965 (63.34%) | 50,479 (58.94%) | ||

| Single | 1484 (9.43%) | 11,411 (13.32%) | ||

| Divorced | 1539 (9.78%) | 8618 (10.06%) | ||

| Widowed | 2611 (16.60%) | 14,263 (16.65%) | ||

| Separated | 134 (0.85%) | 878 (1.03%) |

- Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

3.5 The risk of suicide among patients with PDAC stratified by time since diagnosis

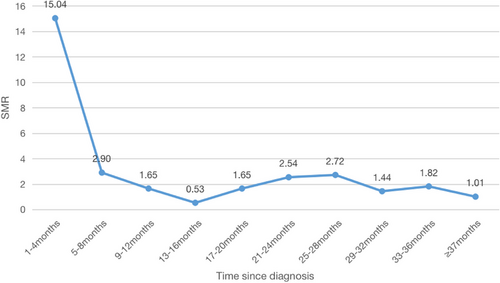

Table 5 and Figure 3 illustrate the progression of the SMR among patients. Notably, the highest SMR was observed within the initial 1–4 months following PDAC diagnosis (SMR = 15.04, 95% CI: 11.05–20.00). Subsequently, within the 13–16-month post-diagnosis period, the SMR dropped to its lowest point (SMR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.06–1.91). However, the suicide rate then exhibited an upward trend, culminating in a peak of 2.72 at 25–28 months. Remarkably, 3-year post-diagnosis, the SMR of PDAC patients returned to a level statistically similar to that of the wider US population (SMR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.21–2.96).

| Time since diagnosis (months) | Patients with PDAC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed deaths, n (%) | Mortality ratea | Expected deaths | SMR (95%CI) | |

| 1–4 | 47 (53.41) | 183.17 | 3.13 | 15.04 (11.05–20.00) |

| 5–8 | 13 (14.77) | 35.32 | 4.48 | 2.90 (1.54–4.96) |

| 9–12 | 8 (9.09) | 20.10 | 4.85 | 1.65 (0.71–3.25) |

| 13–16 | 2 (2.27) | 6.45 | 3.78 | 0.53 (0.06–1.91) |

| 17–20 | 4 (4.55) | 20.10 | 2.43 | 1.65 (0.54–3.84) |

| 21–24 | 4 (4.55) | 30.93 | 1.58 | 2.54 (0.52–7.41) |

| 25–28 | 3 (3.41) | 33.13 | 1.10 | 2.72 (0.56–7.96) |

| 29–32 | 2 (2.27) | 17.54 | 0.75 | 1.44 (0.32–9.52) |

| 33–36 | 1 (1.14) | 22.16 | 0.55 | 1.82 (0.04–6.49) |

| ≥37 | 4 (4.55) | 12.30 | 3.95 | 1.01 (0.21–2.96) |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence intervals; SMR, standardized mortality ratio.

- a Per 100,000 person-years.

4 DISCUSSION

The risk of noncancer deaths surpasses that of cancer deaths with the rapid development of medical technology.10 More and more importance has been attached to noncancer deaths nowadays, especially suicidal deaths.11-13 It is noteworthy that the suicide rate in patients with PDAC has been vastly increasing recently. An English study spanning 1995–2015 highlighted PDAC patients’ suicide rate as the second highest among all cancer types,9 a stark contrast to earlier data.10

To delve deeper into the associated suicide risk among PDAC patients, we conducted a comprehensive study utilizing the SEER database. Our findings revealed that all subgroups of PDAC patients exhibited a heightened risk of suicide compared to the general US population. The SMR for PDAC patients stood at 3.51 (95% CI: 2.81–4.32). Employing the Nelson–Aalen estimator and the Fine and Grey method allowed us to discern the distinct contributions of each variable to the suicide rate among PDAC patients. Notably, gender emerged as a pivotal independent factor in suicide-specific mortality. Male PDAC patients bore an exponentially higher risk of suicide compared to their female counterparts, with an SMR of 3.64 (95% CI: 2.90–4.53), a striking contrast to females (SMR = 1.59, 95% CI: 0.64–3.28). These results affirm that the female gender serves as a robust protective factor against suicidal tendencies in PDAC patients, in line with previous studies.9 Numerous investigations have highlighted a higher susceptibility to suicide in male patients across various tumor types.12, 14 We posit that upon receiving an unexpected cancer diagnosis, male patients may grapple with obsessive depression for an extended period compared to females, potentially exacerbated by increased pain.15 This interplay of depression and PDAC-induced discomfort can significantly impact one's overall quality of life.16, 17

Additionally, patients who did not undergo chemotherapy exhibited a higher likelihood of experiencing poorer clinical outcomes (HR = 1.650, 95% CI = 1.054–2.584, p = 0.029). This observation aligns with the SMR results in our study, which consistently demonstrated an elevated risk (SMR = 6.03, 95% CI = 4.40–8.06). We attribute this phenomenon to two key factors. First, those ineligible for adjuvant chemotherapy often faced cachexia, imposing a greater psychological burden and heightened pain due to the rapid progression of the tumor. As mentioned earlier, advanced-stage tumors inflict severe physical and psychological distress on patients, leading to a tendency toward suicide among this group of patients. Second, those who declined immediate chemotherapy may face significant social, economic, or familial pressures or have insufficient personal coping mechanisms and comfort. It is likely that they were already contending with psychological disorders. Their negative stance toward treatment increased their susceptibility to suicidal thoughts.

There is a growing consensus that unsatisfactory marital status is closely linked with an increased risk of suicide.18, 19 Our analysis affirms that divorced status is independently associated with suicide-specific mortality (HR = 2.333, 95% CI = 1.299–4.192, p = 0.005). Moreover, the SMR for divorced patients surpasses that of all other patient groups (SMR = 6.74, 95% CI: 3.77–11.12). When compared to individuals in other marital statuses, divorced patients demonstrate both reduced overall survival and an elevated risk of suicide. Relevant research indicates that being married is correlated with improved psychological well-being and immune system function.20 It is also believed that the endocrine system benefits from an optimal marital status.21 These combined effects contribute to maintaining homeostasis and alleviating anxiety and depression. Additionally, marital partners often serve as crucial pillars of support during anti-tumor therapy, playing a significant role in preventing suicidal tendencies to a large extent.

Furthermore, our study revealed that patients aged ≥65-year old were at a higher risk of suicide (SMR = 4.06, 95% CI: 3.12–5.21). Nevertheless, when compared to patients under the age of 65, the HR for suicide-specific mortality was 1.470, indicating no significant difference (p = 0.134). To unravel the intrinsic role of age in patients’ suicide risk, we conducted a more granular analysis of suicide rates within different age groups. Notably, patients aged 70–74-year old carried the highest suicide risk (SMR = 5.14, 95% CI: 3.10–8.03). Our examination of the interaction between age groups and all other pertinent variables unveiled that patients diagnosed at 70–74-year old were more likely to present an advanced stage of PDAC. The SMR analysis in our study substantiates this finding by demonstrating that patients with advanced-stage PDAC indeed had a higher suicide rate. This effectively elucidates the heightened suicide risk observed in patients aged 70–74-year old.

Moreover, in relation to the year of diagnosis, both the 2000–2005 and 2006–2011 subgroups exhibited no significant impact on suicide-specific mortality when compared to the 2012–2017 subgroup (p = 0.183). Nonetheless, our study identified an ascending trend in SMR, underscoring a consistent year-on-year growth in suicide risk. This trend aligns with the prolonged life expectancy of PDAC patients, resulting in a diminishing proportion of PDAC-specific mortality within overall causes of death.22 Concurrently, empirical evidence has affirmed an annual surge in suicides, particularly among cancer patients.10 Consequently, we surmise that the challenge of managing suicide risk in PDAC patients is poised to become even more complex in the forthcoming years.

Although previous studies on gastric and ovarian cancers have demonstrated an elevated risk of suicide-specific mortality among patients with advanced-stage tumors,23, 24 our investigation reveals a distinctive pattern in PDAC. Contrary to expectations, we found no significant disparities in suicide-specific mortality among patients across different PDAC stages. This intriguing finding suggests that the profound impact of a PDAC diagnosis transcends the conventional considerations of the tumor stage. PDAC stands out for its notably high malignancy and grim prognosis, despite significant strides in medical technology.25-27 Even individuals diagnosed with an ostensibly early-stage PDAC may grapple with the overwhelming emotional burden of the disease's relentless course. Moreover, the neurotropic characteristics and aggressive nature of PDAC subject patients to unparalleled levels of distress in comparison to other malignancies.28, 29 Given these unique challenges, it is entirely plausible that suicide-specific mortality rates in PDAC patients remain relatively consistent across diverse tumor stages.

Although some reports suggest that patients undergoing surgery, particularly extended radical procedures, face an elevated risk of suicide,24 our study yields different insights. The traditional viewpoint attributes this heightened risk to the often numerous and severe postoperative complications, which can significantly impact a patient's functional abilities and overall quality of life. However, in the case of PDAC, our findings reveal a nuanced picture. Given the generally poor prognosis and limited life expectancy associated with PDAC, the impact of complications on postoperative quality of life may not be as pronounced as in other contexts. Additionally, the field of surgical intervention for PDAC has witnessed remarkable advancements in recent years.30 The integration of interventional radiology techniques, for instance, has notably curtailed the need for reoperation in cases involving clinical-related fistulas and fluid collections.31 High-volume centers, too, have achieved substantial progress in managing complications following extended pancreatectomy procedures.32 Therefore, our study suggests that, in the realm of PDAC, the risk of suicide does not significantly differ across different surgical subgroups.

In order to examine the connection between suicide risk and the duration since diagnosis, we conducted a detailed analysis of the SMR in PDAC patients, categorized by time since diagnosis. Our findings disclosed a notable pattern: Patients exhibited the highest likelihood of committing suicide in the initial months following diagnosis (1–4 months, SMR = 15.04, 95% CI = 11.05–20.00). This trend is highly plausible, as the diagnosis of PDAC often delivers a profound emotional impact on patients. Subsequently, as patients gradually came to terms with their condition, the SMR showed a steady decline. However, a noteworthy uptick was observed at 13–16 months, peaking at 25–28-month post-diagnosis with an SMR of 2.72. Studies have indicated that PDAC recurrence typically transpires within 1–2-year post-surgery.26 The anxiety surrounding recurrence, coupled with the pain induced by subsequent therapies, could contribute to the heightened risk of suicide during this specific period. After this critical juncture, the SMR of PDAC patients gradually returned to a level consistent with the general population (≥37 months, SMR = 1.01).

Although our study did not encompass data on psychological status, we hold the belief that interventions involving antidepressants and therapeutic treatments could prove highly beneficial to PDAC patients. Encouraging outcomes have been documented in patients who have undergone psychological therapy.33, 34 This underscores the imperative for robust psychological education and awareness campaigns. Additionally, sustained vigilance over the mental and emotional well-being of PDAC patients, especially those identified as being at a higher risk of suicide, is crucial. Focused efforts to ameliorate modifiable risk factors, encompassing psychiatric illness and pain management, have the potential to significantly diminish the risk of suicide. This, in turn, promises an enhancement in overall quality of life and prognosis.

4.1 Limitations

There are several limitations that also warrant emphasis. First, the SEER database does not include information on psychological status, preventing a direct assessment of the relationship between mental health and suicide risks. In addition, the data on radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the SEER database is indeed not sufficiently detailed, which to some extent affects the precision of our research conclusions. Second, our study primarily pertains to a US-based population, and the generalizability of our findings to PDAC patients in other countries remains uncertain. Finally, the retrospective design of our study may introduce statistical biases. Prospective studies are warranted to comprehensively evaluate the interplay between clinical factors and the risk of suicide.

4.2 Clinical implications

This manuscript represents the inaugural investigation into suicide risk among PDAC patients, shedding light on factors influencing suicide-specific mortality. The findings underscore the elevated risk of suicide among PDAC patients compared to the general population, emphasizing the imperative for vigilant psychological monitoring in this demographic. Particularly, female patients, those who are divorced, or those who forego chemotherapy necessitate heightened clinical attention and closer follow-up. We advocate for immediate interventions, such as cognitive and dialectical behavior therapy, for individuals exhibiting a heightened suicide risk.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our study reveals an alarmingly high suicide rate among patients with PDAC. Sex, chemotherapy status, and marital status emerged as pivotal, independent prognostic factors for suicide-specific mortality in this group. Notably, we observed a persistent annual increase in suicide risk among PDAC patients. Furthermore, individuals aged 70–74 faced a significantly higher suicide risk, with distinct peaks occurring at 1–4 and 25–28 months after diagnosis. In light of these concerning findings, we urgently advocate for systematic psychological monitoring of all PDAC patients, with timely consideration of antidepressant therapy for those at elevated suicide risk. We firmly believe that robust suicide prevention and intervention measures can substantially enhance overall survival rates for individuals grappling with PDAC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concepts: Chao Wang, Haoda Chen, and Yuanchi Weng. Study design: Chao Wang, Haoda Chen, and Baiyong Shen. Data acquisition; quality control of data and algorithms: Chao Wang and Weishen Wang. Data analysis and interpretation; manuscript editing: Chao Wang and Haoda Chen. Statistical analysis: Chao Wang and Yuanchi Weng. Manuscript preparation: Chao Wang and Xiaxing Deng. Manuscript review: Weishen Wang and Baiyong Shen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express gratitude to the Autonomous Committee on Standardized Residency Training of Ruijin Hospital for instructive advice and useful suggestion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Baiyong Shen is an Editorial Board member of Aging and Cancer and a co-author of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not required because of the public nature of all the presented data.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data of our work are available and publicly accessible. The original data comes from the SEER database.