Chiral Heterobimetallic Bismuth–Rhodium Paddlewheel Catalysts: A Conceptually New Approach to Asymmetric Cyclopropanation

Dr. Lee R. Collins

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorSebastian Auris

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorDr. Richard Goddard

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorCorresponding Author

Prof. Alois Fürstner

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorDr. Lee R. Collins

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorSebastian Auris

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorDr. Richard Goddard

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorCorresponding Author

Prof. Alois Fürstner

Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, 45470 Mülheim/Ruhr, Germany

Search for more papers by this authorDedicated to Professor Walter Thiel on the occasion of his 70th birthday

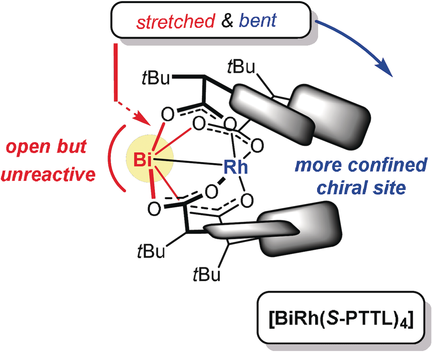

Graphical Abstract

Stretched and Bent: Formal replacement of one Rh atom in a classical dirhodium tetracarboxylate paddlewheel complex by Bi results in a conical shape of the precatalyst: while the wide-open Bi site does not cause a racemic background reaction, the calyx-like chiral binding pocket around Rh is narrower and hence more effective. These two virtues likely synergize in asymmetric cyclopropanation reactions.

Abstract

Cyclopropanation reactions of styrene derivatives with donor–acceptor carbenes formed in situ are significantly more enantioselective when catalyzed by the heterobimetallic bismuth–rhodium complex 5 a endowed with N-phthalimido tert-leucine paddlewheel ligands rather than by its homobimetallic dirhodium analogue 1 a. This virtue is likely the result of two synergizing factors: the conical shape of 5 a translates into a narrower calyx-like chiral binding site about the catalytically active Rh center; the Bi atom, although fully solvent exposed, does not decompose aryl diazoacetates and is hence incapable of promoting a racemic background reaction. Moreover, ligand variation proved that successful catalyst design mandates that the anisotropy of the conical heterobimetallic core be matched by proper directionality of the ligand sphere.

Supporting Information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

| Filename | Description |

|---|---|

| anie201900265-sup-0001-misc_information.pdf6 MB | Supplementary |

Please note: The publisher is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing content) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1C. Werlé, R. Goddard, P. Philipps, C. Farès, A. Fürstner, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10760–10765; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 10918–10923.

- 2For the first structures of non-chiral electrophilic dirhodium carbene complexes in the solid state, see:

- 2aC. Werlé, R. Goddard, A. Fürstner, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15452–15456; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 15672–15676;

- 2bC. Werlé, R. Goddard, P. Philipps, C. Farès, A. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3797–3805; see also:

- 2cD. J. Tindall, C. Werlé, R. Goddard, P. Philipps, C. Farès, A. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 1884–1893.

- 3

- 3aS. Hashimoto, N. Watanabe, S. Ikegami, Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 5173–5174;

- 3bN. Watanabe, T. Ogawa, Y. Ohtake, S. Ikegami, S. Hashimoto, Synlett 1996, 85–86;

- 3cS. Kitagaki, M. Anada, O. Kataoka, K. Matsuno, C. Umeda, N. Watanabe, S. Hashimoto, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1417–1418;

- 3dH. Tsutsui, T. Abe, S. Nakamura, M. Anada, S. Hashimoto, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 1366–1368.

- 4F. G. Adly, Catalysts 2017, 7, 347.

- 5

- 5aM. P. Doyle, D. C. Forbes, Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 911–935;

- 5bH. M. L. Davies, R. E. J. Beckwith, Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2861–2904;

- 5cA. Ford, H. Miel, A. Ring, C. N. Slattery, A. R. Maguire, M. A. McKervey, Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9981–10080;

- 5dH. Lebel, J.-F. Marcoux, C. Molinaro, A. B. Charette, Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 977–1050;

- 5eA. DeAngelis, R. Panish, J. M. Fox, Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 115–127;

- 5fZ. Zhang, J. Wang, Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 6577–6605;

- 5gS.-F. Zhu, Q.-L. Zhou, Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1365–1377;

- 5hH. M. L. Davies, J. R. Manning, Nature 2008, 451, 417–424.

- 6Various geometries had previously been considered; for a discussion, see ref. [1]. Based on the structure of [Rh2(PTTL)4]⋅EtOAc, it was first proposed by Fox and co-workers that an “all up” conformation might account for asymmetric cyclopropanation, see:

- 6aA. DeAngelis, O. Dmitrenko, G. P. A. Yap, J. M. Fox, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7230–7231;

- 6bA. DeAngelis, D. T. Boruta, J.-B. Lubin, J. N. Plampin, G. P. A. Yap, J. M. Fox, Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4541–4543.

- 7The relevance of the chiral crown conformation originally proposed by Fox et al. was subsequently considered (but also partly challenged) by other authors, see:

- 7aV. N. G. Lindsay, W. Lin, A. B. Charette, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16383–16385;

- 7bA. Ghanem, M. G. Gardiner, R. M. Williamson, P. Müller, Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 3291–3295;

- 7cJ. T. Mattiza, J. G. G. Fohrer, H. Duddeck, M. G. Gardiner, A. Ghanem, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 6542–6550;

- 7dT. Goto, K. Takeda, N. Shimada, H. Nambu, M. Anada, M. Shiro, K. Ando, S. Hashimoto, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6803–6808; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 6935–6940;

- 7eY.-S. Xue, Y.-P. Cai, Z.-X. Chen, RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 57781–57791.

- 8F. G. Adly, M. G. Gardiner, A. Ghanem, Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 3447–3461.

- 9The conformers with C2 or D2 symmetry comprise two equivalent Rh atoms, whereas the conformers with C4 or C1 symmetry expose two different Rh centers to a reaction partner.

- 10In the solid state, the α,α,α,α-conformer adopted by 3 is not strictly C4 symmetric because the aperture of the chiral binding site has a longer and a shorter dimension; in CD2Cl2 solution at −50 °C, however, a single set of resonances was recorded, suggesting that this slight distortion averages out on the NMR time scale.

- 11R. P. Reddy, G. H. Lee, H. M. L. Davies, Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 3437–3440.

- 12BiRh paddlewheel complexes were originally described in:

- 12aE. V. Dikarev, T. G. Gray, B. Li, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1721–1724; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 1749–1752;

- 12bE. V. Dikarev, B. Li, H. Zhang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2814–2815;

- 12cA. S. Filatov, M. Napier, V. D. Vreshch, N. J. Sumner, E. V. Dikarev, M. A. Petrukhina, Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 566–571; see also:

- 12dT. L. Sunderland, J. F. Berry, Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 50–55;

- 12eT. L. Sunderland, J. F. Berry, J. Coord. Chem. 2016, 69, 1949–1956.

- 13For a first application in synthesis, see: J. Hansen, B. Li, E. Dikarev, J. Autschbach, H. M. L. Davies, J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 6564–6571.

- 14L. R. Collins, M. van Gastel, F. Neese, A. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 13042–13055.

- 15Some π-acidity, however, is manifest in the structure of [BiRh(TFA)4] co-crystallized with pyrene, in which the Bi atom engages in η6-coordination with this ligand, see: E. V. Dikarev, B. Li, A. Y. Rogachev, H. Zhang, M. A. Petrukhina, Organometallics 2008, 27, 3728–3735.

- 16

- 16aZ. Ren, T. L. Sunderland, C. Tortoreto, T. Yang, J. F. Berry, D. G. Musaev, H. M. L. Davies, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10676–10682;

- 16banother chiral Bi–Rh complex is described in ref. [12b], but no applications were reported.

- 17Water eventually coordinates to the Rh center as shown, for example, by the structure of [BiRh(esp)2]⋅H2O in the solid state, which is contained in the Supporting Information of ref. [14].

- 18It is also comparable to the structure of 1 a⋅EtOAc, see ref. [6].

- 19For pertinent examples see the following and literature cited therein: G. Seidel, A. Fürstner, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4807–4811; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 4907–4911.

- 20For [RhRh(TCPTTL)4] and related complexes, see:

- 20aM. Yamawaki, H. Tsutsui, S. Kitagaki, M. Anada, S. Hashimoto, Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 43, 9561–9564;

- 20bT. Goto, K. Takeda, M. Anada, K. Ando, S. Hashimoto, Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4200–4203;

- 20cH. Tsutsui, Y. Yamaguchi, S. Kitagaki, S. Nakamura, M. Anada, S. Hashimoto, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2003, 14, 817–821.

- 21

- 21aK. M. Chepiga, C. Qin, J. S. Alford, S. Chennamadhavuni, T. M. Gregg, J. P. Olson, H. M. L. Davies, Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 5765–5771;

- 21bH. M. L. Davies, G. H. Lee, Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1233–1236.

- 22V. N. G. Lindsay, A. B. Charette, ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1221–1225.

- 23G. Cavallo, P. Metrangolo, R. Milani, T. Pilati, A. Priimagi, G. Resnati, G. Terraneo, Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601.

- 24For other recent contributions to carbene chemistry, see:

- 24aA. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11–24;

- 24bA. Guthertz, M. Leutzsch, L. M. Wolf, P. Gupta, S. M. Rummelt, R. Goddard, C. Farès, W. Thiel, A. Fürstner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3156–3168;

- 24cA. G. Tskhovrebov, R. Goddard, A. Fürstner, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8089–8094; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 8221–8226.