The Effects of Training on the Competitive Economic Advantage of Companies in Spain

Abstract

The search for factors that lead to competitive advantage in a company in relation to its competitors is a widely debated subject; a wide range of issues have been examined to determine which factors are the most influential. The aim of this paper is to study training effect on business results (particularly on firm’s financial turnover). For the present research, the classical model of Industrial Economy as a frame of reference has been used. The data collection instrument was a questionnaire sent to 381 large organizations in Catalonia (Spain) during 2009 and 2010. The empirical section of the present article was developed using structural equation modeling (SEM). Results relate training to company’s financial turnover in a positive way. The General Expenditure and Costs is the variable that most contributes to the explanation of firms’ financial turnover. The Organization of Training variable is the second most important construct to account for financial turnover However, training is required to be well organized as well as properly financed.

1. Introduction

Fifty years ago, a number of leading economists laid the foundations of what has become an indisputable claim in the field of economy, namely, that education and training are essential to all developmental processes. Among such experts were Mincer [1], Schultz [2], and Becker [3]. They pointed out that a close link is to be found between training and such key economic variables as profit levels, employment, and GDP growth. Later, numerous contributions have been made to the field [4, 5], and, in today’s world of business, the main objectives include obtaining competitive advantage, increasing financial turnover and profits, and enhancing labor productivity through the introduction of new strategies in Human Resource Management (HRM). The latter includes training based on the fact that a company’s staff is now recognized as being one of its main assets. In fact, a company’s survival strongly depends on its capacity to capture intelligence, transform it into knowledge, incorporate that new knowledge into organizational training, and disseminate it quickly throughout the company [6–10].

From an organizational perspective, training and the pursuit of excellence through learning enable companies to improve their profitability by modifying their employees’ skills and attitudes [11, 12] and by increasing their job satisfaction [13] and commitment to the company [14]. In this sense, it seems that a company that invests in training and development tends to have more success [14–17] than the one that does not. If companies consider their staff as strategically valuable assets, then managers should state that a competent and devoted labor force constitutes a prerequisite for business achievements [18]. In this sense, continuous training contributes to the improvement, updating, and recycling the knowledge and skills required to a company’s employees.

In this paper, the relationship between training and business outcomes is analyzed by conducting a survey with 381 large companies in the Spanish region of Catalonia during 2009 and 2010. The methodology adopted included the following: first, the data are derived from a survey designed especially for large firms; second, the dependent and independent variables are explored through factor analysis; finally, a structural model is used as a method of analysis.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we summarize previous empirical evidence on training and business performance; secondly, the data and the methodology of analysis are presented; finally, the main results and conclusions are presented.

2. Literature Review: Training and Economic Performance of Firms

This section examines existing studies on the impact of training on a company’s competitive economic advantage. Given the vast output in the field, the review is limited to a number of studies that highlight the positive relationship between training and two key factors for measuring business success: profits and productivity.

Concerning profits, drawing on data for 5,824 private-sector organizations operating in 26 countries, Hansson [19] concludes that the single most important factor associated with profitability is the amount a firm invests in training, concluding that the economic benefits of training outweigh the cost of staff financial turnover. Likewise, Bassi et al. [20] show a positive and significant relationship between investment in training and total returns for shareholders in a sample of US companies. Specifically, they find that education and training result in an 18% increase in total returns for shareholders, whereas the rate of return in companies that do not provide training is only 12%. Similarly, Molina and Ortega [21] analyze the impact of employee training on company profits, measured in terms of Tobin’s Q ratio and the total return to shareholders of North American companies, and conclude that a high incidence of training has a positive effect on company profits through factors such as employee satisfaction and customer loyalty. In addition, Myers et al. [22] find a positive relation between company profits and employee education and skills, while Guerrero and Barraud-Didier [23], in a sample of 1,530 large companies in France, report that 4.6% of the variance in financial performance is attributable to training. Likewise, Ng [24] concludes that if workers in Shanghai (China) receive additional external training, profits increase by 2%. Likewise, Akhtar et al. [25] show the positive effects of training (and other HRM practices) on the financial results of a sample of 465 Chinese enterprises. Finally, Aragon and Valle [26] analyze a sample of Spanish managers who show that the intensity of their training positively affects financial performance.

As for productivity, based on a survey of companies with more than 100 employees in the United States, which operate in both the production and nonproduction sectors, Black and Lynch [27] conclude that a 10% increase in education leads to an 8.5% increase in productivity in the production sector and a 12.7% increase in the nonproduction sector. Along the same line, Bartel [28] shows that, although informal training has no impact on productivity, formal training outside work has a positive and significant impact. Moreover, analyzing 157 companies in the United States, Holzer et al. [29] report that training during the first year of employment reduces the rate of defective work by 7%. They also claim that half of the defects disappear during the subsequent year. Based on a unique firm-level dataset from five developing countries and using a production function model (where the dependent variable is the logarithm of added value), Tan and Batra [30] show that training has a positive effect on productivity confirming everything stated so far.

More recently, using a group of British manufacturing companies between 1983 and 1996, Dearden et al. [31] find that work-related training is associated with significantly higher productivity (a 1% increase in training is associated with an increase in value added of about 0.6% per hour). Moreover, Percival et al. [32] show that training has a positive effect on productivity in 12 out of 14 manufacturing companies examined in Canada. In a qualitative analysis, Cooke [33] reviews the strategies used by British companies to enhance workers’ productivity. He found that employees who receive training are significantly better prepared to do their work more efficiently, with a greater sense of responsibility, creativity, job satisfaction, and personal motivation. Cooke also found that such training and subsequent positive outcome lead the organization to improve its productivity in the long term. Several studies conducted in various European countries highlight the benefits of training associated with apprenticeship [34]. Others report the benefits of external or general training; however, the benefits are negligible in the case of internal or specific training [35]. Finally, Ballot et al. [36] consider that investment in physical capital, training, and R&D are complementary. In the context of a study on companies in France and Sweden, the authors report that firms obtain the largest part of the returns from their investments through productivity increase. Nonetheless, the share is lower for intangible assets (R&D and training) than it is for physical capital. Finally, Úbeda-García et al. [37] stress the effect of training on both productivity and financial performance. They conclude that training policy positively correlates with both variables—profits and productivity—based on a sample of Spanish hotels.

3. Data

The data collection instrument was a survey designed for this study and conducted in 2009 and 2010 with a group of 381 large companies (more than 250 employees) in the region of Catalonia (one of the richest regions of Spain). These companies reported a financial turnover of at least 24 million euros and included public and private companies with both domestic and foreign capital. Information about the companies came from two sources: the independent (training) variables and the dependent (economic) ones. The former ones were collected in-line with the survey designed by Pons-Peregort [38] and Eguiguren-Huerta [39], while the latter ones were obtained from the SABI database (Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System) and from the “Fomento de la Producción” magazine. The response rate of surveyed companies was 28%, which gives a total of 106 companies, which were contacted by telephone in order to schedule a personal interview or, alternatively, to arrange that the questionnaire be answered and sent by post or email. Interviews were conducted in company; telephone follow-ups were made to CEOs and HR Directors to provide support to interviewees filling out the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted in a total of 63 questions divided into three sections: first, the organization descriptive information; second, aspects related to the firm organizational structure and the role of training; and, third, management control over training. The questionnaire was pretested. The initial questionnaire was sent to a group of experts, including individuals from industry and academia, who had direct contact with the field of training. The pretest served to identify errors in the initial questionnaire and, therefore, to validate the test. Experts’ comments were collected in order to identify the questions which might contain a degree of ambiguity derived from their wording or their being presented in an inappropriate order. The confidence level was 99% (z = 2.58) with a statistical error of ±2.99 (for a confidence level of 99% in which p = q = 0.5).

4. Factor Analysis

Once the information about training and economic activity had been collected, factor analysis was used to identify the constructs or latent variables that define the model. This approach favored the simplification of the dimensions of the measure model, and, given the characteristics of the method, it allowed the analysis of how almost 30 variables were grouped.

The factors were extracted using the principal component method. To do so a Varimax rotation was used; this procedure yielded results that justified the application of the method (see Table 1). In all cases, the values obtained satisfy the recommendations by Dziuban and Shirkey, who claim that if the KMO value is ≥ 0.5, then, factor analysis is acceptable [40]. An exploratory factor analysis applied to the training variables showed the total expected variance to be approximately 62%. This value is higher than the one stipulated for research in the social sciences, in which a value of 50% is deemed satisfactory [41].

| KMO and Bartlett’s test—formation variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Measure of sampling adequacy—Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin | 0.544 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approximate Chi-square | 1,628.792 |

| Df | 561 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| KMO and Bartlett’s test—year 2009 | ||

| Measure of sampling adequacy—Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin | 0.685 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approximate Chi-square | 1,306.591 |

| Df | 231 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| KMO and Bartlett’s test—year 2010 | ||

| Measure of sampling adequacy—Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin | 0.675 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approximate Chi-square | 1,201.997 |

| Df | 253 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

The variables were grouped into factors with a high degree of theoretical relationship. This grouping enabled each factor to be identified with the phenomenon that it sought to measure. In the case of the training variables, the resulting components were the following: Evaluation of Training, Importance of Training, Basic Training, Source of Training, Organization of Training, Seniority of Training, and Training Costs (see Table 2). On the other hand, the economic variables included General Expenditure and Costs, Profitability, Productivity and Unit Labor Costs, Size and Costs, Earnings, and financial turnover (see Table 2). The results of the exploratory factor analysis pointed to a high percentage of total variance (88% and 87% in 2009 and 2010, resp.). In addition, the variables were grouped as expected, that is, indicating the best possible results obtained and presenting a high degree of correlation and natural grouping, according to the original hypothesis. In the case of the economic variables, the factors remained meaningful for variables that, theoretically, presented a considerable degree of coherence. The results obtained also enabled each factor to be identified with the phenomenon that it sought to measure.

| Factor extracted | Assigned factor name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Training variables | ||

| Factor 1 | Evaluation of Training | ET |

| Factor 2 | Importance of Training | IT |

| Factor 3 | Basic Training | BT |

| Factor 4 | Source of Training | SOT |

| Factor 5 | Organization of Training | OT |

| Factor 6 | Seniority of Training | ST |

| Factor 7 | Training Costs | TC |

| Economic variables | ||

| Factor 1 | General Expenditure and Costs | GEC |

| Factor 2 | Profitability | P |

| Factor 3 | Productivity and Unit Labor Costs | PULC |

| Factor 4 | Size and Costs | SC |

| Factor 5 | Earnings | E |

| Factor 6 | Financial turnover | T |

5. The Structural Equation Model

Once the training variables had been related to groups not directly measurable, the corresponding methodology was used to estimate the impact of training on a firm financial turnover. To do so, a structural equation model (SEM) was used. This methodology requires the estimation of two submodels; in the first one, the measure model is composed of the latent variables, not observable, with their observed indicators, following the selected model. Once this measure model has been estimated and validated, the second stage of the SEM consists in estimating the structural model, which relates the latent variables among themselves [42]. This model enables researchers to quantify the relationship among each training factor and the selected dependent variable.

The evaluation of the measurement model seeks to determine whether the theoretical concepts measure the observed variables correctly. Such evaluation consists in the analysis of the construct reliability individually, the internal consistency or reliability of the scale, and convergent and discriminant validity. The structural model evaluates the weight and magnitude of the relationships among variables through R2 and standardized β coefficients [43].

In assessing the measurement model, individual item reliability (Tables 3(a) and 3(b)) and construct reliability (Table 4) are considered. In a Partial Least Square (PLS) model, individual item reliability is assessed by examining the loads (λ) or by using simple measure correlations or indicators with their respective construct. The most widely accepted empirical rule is the one proposed by Carmines and Zeller [44], who state that for an indicator to be accepted as part of a construct, it needs to have a load equal to or greater than 0.7. Tables 3(a) and 3(b), show the reliability of the items for years 2009 and 2010. The assessment of the reliability of a construct allows to check the internal consistency of all indicators measuring the concept (how indicators rigorously measure latent variables with which they are associated). In order to assess the reliability of the construct two coefficients are used: composite reliability (ρc) as proposed by Werts et al. [45] and Cronbach’s alpha. The composite reliability coefficient proposed by Barclay et al. [46] and Fornell and Larcker [47] was chosen since this factor cannot, among other features, be influenced by the number of elements present in the scale. In both techniques composite reliability values are acceptable above or very close to 0.7. Therefore, the construct reliability can be confirmed, as shown in Table 4.

| T | GEC | ET | ET | OT | OT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ |

| t1 | 0.8421 | ge1 | 0.8471 | IT | 0.7238 | ST | 0.6790 | IT | 0.8512 | ST | 0.8802 |

| t2 | 0.7811 | ge2 | 0.8024 | it1 | 0.6966 | st1 | 0.7685 | it1 | 0.8322 | st1 | 0.7162 |

| t3 | 0.7506 | ge3 | 0.6900 | it2 | 0.7170 | st2 | 0.8561 | it2 | 0.7136 | st2 | 0.8353 |

| ge4 | 0.7950 | it3 | 0.7742 | st3 | 0.8326 | it3 | 0.7170 | st3 | 0.8768 | ||

| ge5 | 0.7920 | it4 | 0.8770 | st4 | 0.7830 | it4 | 0.8016 | st4 | 0.7582 | ||

| ge6 | 0.8502 | it5 | 0.8756 | st5 | 0.8852 | it5 | 0.8288 | st5 | 0.8161 | ||

| ge7 | 0.8237 | it6 | 0.7555 | st6 | 0.7566 | it6 | 0.7749 | st6 | 0.7670 | ||

| ge8 | 0.7733 | TB | 0.7691 | st7 | 0.7983 | TB | 0.7496 | st7 | 0.7385 | ||

| ge9 | 0.7075 | tb1 | 0.8346 | st8 | 0.8257 | tb1 | 0.7611 | st8 | 0.7739 | ||

| ge10 | 0.7330 | tb2 | 0.7865 | PT | 0.8351 | tb2 | 0.7944 | PT | 0.7593 | ||

| ge10 | 0.8188 | pt1 | 0.7229 | pt1 | 0.7889 | ||||||

| ge12 | 0.7879 | pt2 | 0.8478 | pt2 | 0.8695 | ||||||

| T | GEC | ET | ET | OT | OT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ | Item | λ |

| t1 | 0.7412 | ge1 | 0.8321 | IT | 0.8241 | ST | 0.7808 | IT | 0.7873 | ST | 0.8235 |

| t2 | 0.6835 | ge2 | 0.7938 | it1 | 0.7976 | st1 | 0.6629 | it1 | 0.8129 | st1 | 0.6271 |

| t3 | 0.8560 | ge3 | 0.7223 | it2 | 0.6977 | st2 | 0.7415 | it2 | 0.7937 | st2 | 0.8254 |

| ge4 | 0.7348 | it3 | 0.8125 | st3 | 0.7922 | it3 | 0.7260 | st3 | 0.8385 | ||

| ge5 | 0.7835 | it4 | 0.8077 | st4 | 0.8209 | it4 | 0.8161 | st4 | 0.7386 | ||

| ge6 | 0.8208 | it5 | 0.6731 | st5 | 0.6882 | it5 | 0.7878 | st5 | 0.7869 | ||

| ge7 | 0.7973 | it6 | 0.7402 | st6 | 0.8256 | it6 | 0.7594 | st6 | 0.7580 | ||

| ge8 | 0.7554 | TB | 0.8018 | st7 | 0.7983 | TB | 0.7162 | st7 | 0.7737 | ||

| ge9 | 0.6758 | tb1 | 0.7357 | st8 | 0.8164 | tb1 | 0.7416 | st8 | 0.7998 | ||

| ge10 | 0.6389 | tb2 | 0.6841 | PT | 0.7235 | tb2 | 0.8046 | PT | 0.7593 | ||

| ge10 | 0.7781 | pt1 | 0.6279 | pt1 | 0.7677 | ||||||

| ge12 | 0.7765 | pt2 | 0.7944 | pt2 | 0.8294 | ||||||

| Construct | Composite reliability (ρc) 2009 | AVE 2009 | Composite reliability (ρc) 2010 | AVE 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 0.8960 | 0.6857 | 0.7952 | 0.5685 |

| BT | 0.9207 | 0.6290 | 0.7568 | 0.5902 |

| SOT | 0.8488 | 0.5709 | 0.8167 | 0.6629 |

| GEC | 0.8579 | 0.5836 | 0.7739 | 0.6946 |

| ST | 0.9371 | 0.7009 | 0.8202 | 0.6823 |

| TC | 0.8794 | 0.6123 | 0.8813 | 0.7112 |

| ET | 0.8925 | 0.6845 | 0.7854 | 0.5850 |

| OT | 0.8890 | 0.6082 | 0.8670 | 0.6175 |

| T | 0.9133 | 0.6110 | 0.8419 | 0.6249 |

As for variance, the measure provided by the AVE is used to interpret the indicators of each construct for comparative purposes. Following the analysis of the measurement model and having analyzed the construct reliability, both convergent and discriminant validity were examined. Convergent validity analyzes whether the different items used to measure a concept or construct actually do so. Fornell and Larcker [47] state that the average variance extracted (AVE) should be greater than 0.50, which is set at more than 50% of the construct variance. As shown in Tables, 5(a) and 5(b), the adjustment of these items is significant and highly correlated.

| IT | BT | SOT | GEC | ST | TC | ET | OT | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 0.8280 | ||||||||

| BT | 0.7166 | 0.7931 | |||||||

| SOT | 0.6852 | 0.6523 | 0.7556 | ||||||

| GEC | 0.5490 | 0.6180 | 0.7499 | 0.7639 | |||||

| ST | 0.6460 | 0.5932 | 0.6580 | 0.6683 | 0.8371 | ||||

| TC | 0.6221 | 0.5738 | 0.7025 | 0.6958 | 0.8044 | 0.7825 | |||

| ET | 0.5267 | 0.6933 | 0.6763 | 0.6742 | 0.5741 | 0.8273 | |||

| OT | 0.5628 | 0.7125 | 0.5915 | 0.6035 | 0.6318 | 0.7798 | |||

| T | 0.7219 | 0.7998 | 0.7122 | 0.7816 |

| IT | BT | SOT | GEC | ST | TC | ET | OT | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 0.7539 | ||||||||

| BT | 0.5638 | 0.7682 | |||||||

| SOT | 0.7089 | 0.7234 | 0.8141 | ||||||

| GEC | 0.6959 | 0.6876 | 0.7818 | 0.8334 | |||||

| ST | 0.7265 | 0.6977 | 0.7436 | 0.7873 | 0.8260 | ||||

| TC | 0.7369 | 0.6184 | 0.6996 | 0.6789 | 0.8124 | 0.8433 | |||

| ET | 0.6902 | 0.6392 | 0.7997 | 0.7590 | 0.6981 | 0.7648 | |||

| OT | 0.7481 | 0.5995 | 0.6621 | 0.7667 | 0.7257 | 0.7858 | |||

| T | 0.7443 | 0.7188 | 0.7293 | 0.7905 |

6. Results and Discussion

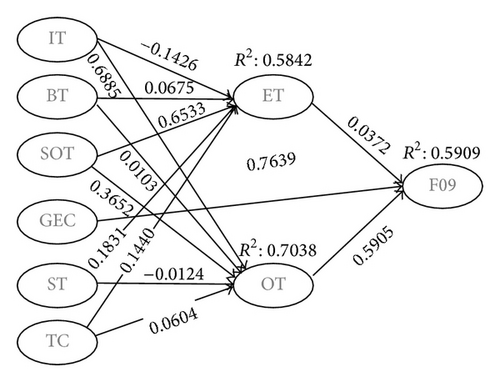

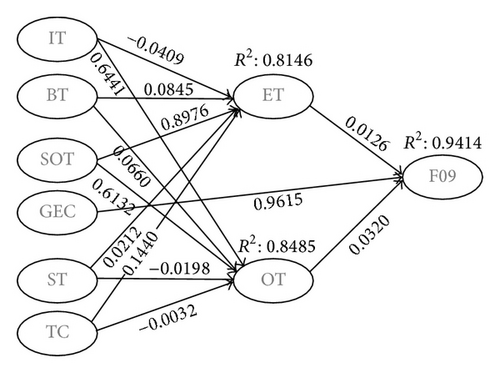

The results show that the model analyzed with the SEM by means of the Partial Least Square integrated with the portable data analysis system gives positive results (Figures 1 and 2 correspond to the models estimated for the two years under consideration).

Table 6 shows the R2 values for the endogenous constructs of the model. They represent the variability of the dependent variable explained by the independent ones. Results are satisfactory since the values of R2 are above 0.5 [41]. Q2 index has been developed by Stone [48] and Geisser [49] which is also analyzed. This index is typically used to measure the predictive relevance or predictability of the dependent constructs. Therefore, Q2 offers a measure of the goodness fit with which the observed values are reconstructed by the model and its parameters [41]. Since the Q2 obtained values for each year considered are positive (0.6391, in 2009, and 0.5931, in 2010, resp.) the predictability of the model is relevant.

| Year 2009 | Year 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | R2 | Construct | R2 |

| Organization of Training | 0.5842 | Organization of Training | 0.8146 |

| Evaluation of Training | 0.7038 | Evaluation of Training | 0.8485 |

| Financial turnover | 0.5905 | Financial turnover | 0.9414 |

While the results are positive, which are in-line with the work by Bassi et al. [20], this research has detected that companies do not link the training plan to business strategy. This flaw may be a reason for not obtaining the expected results. Therefore, companies should take into account not only strategic objectives but also their organizational culture, in this way providing a new alternative to develop, while becoming more competitive in the market [50].

Although this research is focused on studying the relationship between training and financial turnover, the state of the field has shown the correlation between this type of training and positive business performance. This practice considers the private benefits of the market, which benefit those companies that invest in HR training.

However, permanent training opens a set of options which may also have some other type of influence. From a nonmarket point of view, different types of benefits can be obtained as a result of implementing this type of HRM policy. The benefits referred here center on greater self-confidence and better health longevity [51].

From a social point of view, the same author states that permanent training also results in better parenting, higher education of children, lower mobility, reduced crime, and improved civic behavior.

In this line of analysis, according to the scheme presented by Cedefop [52], permanent training benefits are classified into three categories—Society, Business and Groups, and Individuals—distinguishing between market and nonmarket benefits.

First, the category “Society” in the market area comprises the following: economic growth and labor-market outcome, whereas in the field of nonmarket area it includes crime reduction, social cohesion, health, and solidarity between generations. Second, for the Business category in the market area, the benefits list Enterprise Performance and Employee Productivity and, in the nonmarket area, training affects Inclusion and Disadvantaged Groups. Third, for the Individual category, in the market area, the effect is on Employment, Earnings, and Professional Status, whereas, in the nonmarket area, the incidence is on Individual Life Satisfaction and Motivation.

In industrialized countries, OECD examines the relationship between innovation and productivity at enterprise level. The organization demonstrates that investments in human capital and innovation have a positive impact on growth. On the other hand, the report prepared by the Development Bank of Latin America in 2014 [53] states that these investments not only generate new technologies but also absorb the innovations produced by other companies. Investing on human capital results in permanent availability of qualified personnel in order to achieve and exploit various new technological opportunities [54].

7. Conclusions

Over fifty years ago, a number of leading economists, including Mincer [1], Schultz [2], and Becker [3], concluded that a close link is to be found among training and the economic variables of income, employment, and economic and business growth. This study provides empirical evidence that relates training to positive business outcome, defined as firm’s financial turnover. However, training should be well organized and properly financed.

In-line with earlier research, the results in this paper support the assertion that training is one of the Human Resource Management factors firms need to exploit in order to succeed confronting the various challenges they encounter. In a competitive economy, progress is constant, and what today might be a strong market tomorrow can be weak. For a company to stand out from its competitors it needs, among other measures, to create value through the promotion of knowledge, learning, and training in order to innovate and adapt to market changing conditions. However, to maximize training benefits, such procedures as training, planning, executing, and evaluating need to be given due consideration.

The contribution of this study to the field includes two aspects; the first one refers to the existence of the relationship between training and financial turnover. In the state the art, this variable has not been taken into account as an economic outcome. Given the nature of the study, training alone does not guarantee good results and appropriate structure to guarantee the necessary management training should be a must.

The second aspect, the individual and social factor, makes reference to such aspects as professional status, individual motivation, and economic growth, among others. This aspect gives grounds for further research.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.