Does political ideology still matter? A meta-analysis of government contracting decisions

Abstract

In the field of government contracting research, whether and to what extent political ideology drives government contracting has been a subject of ongoing debate for decades. This study conducts a comprehensive meta-analysis, incorporating 418 effect sizes drawn from 68 previous studies spanning over three decades. The findings indicate that right-wing political ideology generally yields a significant, positive effect on driving contracting out. Moreover, meta-regression analysis suggests that this ideological effect is stronger in government contracting for social services and in non-Anglo-American administrative traditions. The results emphasize the enduring relevance of political ideology in government contracting decisions, even though its impact may vary slightly in magnitude and circumstances.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of the New Public Management (NPM) movement in the 1980s, governments in various countries have extensively embraced contracting out as a means of delivering public services (Hodge, 2018; Hood, 1991; Savas, 1987). This prevalent use of contracting out in public service delivery has spurred an extensive body of literature that examines the determinants of government make-or-buy decisions, including economic, political, and managerial factors (e.g., Bel & Fageda, 2009; Chen et al., 2022; Fernandez et al., 2008; Hefetz & Warner, 2012; Lu et al., 2024; Petersen et al., 2015; Schoute et al., 2018; Warner et al., 2021). Within this literature, the impact of political ideology on driving government contracting has been a subject of debate spanning several decades.

Political ideology within democratic partisan politics typically spans the spectrum between left and right viewpoints. Generally, left-wing parties lean toward government intervention, often preferring to retain public service delivery in-house, while right-wing parties favor market-based solutions, leading to a propensity for contracting out public services (Benoit & Laver, 2006; Berry et al., 1998). Historically, the rise of NPM and the increased adoption of contracting out align closely with the emergence of neoliberalism in North America and Western Europe (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004). This shift, prompted by critiques of the public sector's inefficiency, introduced market-oriented policies such as privatization and deregulation (Savas, 1987).

Scholars have posited that political ideology plays a role in shaping government contracting decisions, with suggestions that right-wing governments are particularly inclined toward increased contracting out (e.g., Alonso & Andrews, 2020; Jerch et al., 2017; Lopez-de-Silanes et al., 1997; Schoute et al., 2018; Sundell & Lapuente, 2012). However, the empirical evidence concerning this ideological influence on contracting decisions reveals noteworthy inconsistencies. While a considerable number of studies support the anticipated effect, indicating higher contracting out rates under right-wing governments, an equally substantial body of research contends that political ideology exerts no significant impact on such decisions (e.g., Brudney et al., 2005; González-Gómez & Guardiola, 2009; Pallesen, 2004; Plata-Díaz et al., 2019; Zullo, 2009). These conflicting findings highlight the intricate nature of the relationship between political ideology and government contracting decisions, contributing to a substantial knowledge gap that impedes the achievement of coherent and consistent insights. Furthermore, the observed inconsistencies in primary studies suggest a significant degree of variability in the underlying research, implying that the phenomenon under scrutiny is context-dependent. Consequently, there is a pressing need to scrutinize these results to estimate a more cohesive effect and uncover the circumstances under which the relationship varies.

This study employs meta-analysis to consolidate existing empirical evidence concerning the influence of political ideology on government contracting. It addresses two primary questions: first, what is the overarching effect of political ideology on contracting out, and second, under what circumstances does this influence vary? Drawing upon a meta-analysis of 418 effect sizes from 68 prior studies spanning three decades, our findings indicate that, on average, right-wing ideology exerts a modest yet positive influence on driving contracting out. Further meta-regression analysis reveals a heightened ideological effect in government contracting for social services (as opposed to technical services) and within non-Anglo-American administrative contexts. In conclusion, while the effect of ideology may be small and vary slightly across contexts, our meta-analysis underscores the continued relevance of ideology in government contracting decisions. It contributes by systematically synthesizing diverse findings, resolving empirical inconsistencies, and exploring contextual variations, providing a comprehensive understanding of the influence of political ideology on government contracting decisions and filling a significant knowledge gap in the current literature.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

The interplay between politics and administration has been a persistent debate in public administration. While early scholarship endorsed the politics-administration dichotomy and neutral administrative behaviors (Gulick & Urwick, 1937), its impracticality was soon evident (Appleby, 1949; Gaus, 1950). Kettl (2005) observed that public administration entails both policy and administration aspects: the former involves government roles and accountability, while the latter focuses on operational efficiency and effectiveness. Consequently, understanding public administration issues requires considering both political-policy and economic-management perspectives. In the context of government contracting, while often seen as a cost-efficient tool (Savas, 1987), political motivations in contracting decisions hold equal significance. As Ferris and Graddy (1986) indicated, governments minimize the cost of public service delivery within political and legal constraints. We investigate the role of political ideology in shaping government contracting decisions.

Political ideology provides a framework for individuals to define their social environment and roles. Jacoby (1991, p. 180) posited that ideology “acts as a cognitive structure for people who view the world in an ideological manner.” Broadly, right-wing ideology promotes individualism and supports a self-regulated market, typically aligning with limited government intervention. In contrast, left-wing ideology acknowledges the imperfections of both humans and markets, thereby emphasizing a greater role for governmental involvement. These orientations lead to distinct preferences on policy issues. When an ideology is embraced by the majority of a community, it establishes institutional mechanisms that subsequently shape the norms, values, and rules governing that community (Scott, 2013). Political science theories predict a direct relationship between political ideology and government actions in a democratic regime. For example, representative democracy theory underscores that politicians are elected to represent the interests of their constituents (Besley & Coate, 1997), while partisan politics theory contends that governments tend to enact policies aligned with the ideologies of their political bases (Hibbs, 1977). Within government contracting, right-wing governments are thought to exhibit a greater inclination toward contracting out.

Yet, the empirical evidence regarding the relationship between ideology and contracting remains inconclusive. Certain studies bolster the notion that jurisdictions dominated by right-wing ideologies are prone to increased contracting out. For example, using a regression discontinuity design, Jerch et al. (2017) found that U.S. cities led by Democratic mayors decreased their reliance on contracted public bus services by 6–10%. Similarly, employing a similar design, Alonso and Andrews (2020) showed that in the United Kingdom, local governments under left-wing control were around 40% less prone to outsourcing child welfare services to private providers. Jansson et al. (2021) noted that contracting out was more prevalent among right-leaning municipalities in Sweden, while left-leaning municipalities demonstrated a higher frequency of contracting back-in.

In contrast, another body of research posits that ideology does not influence government contracting decisions. For instance, Pallesen (2004) found no correlation between Danish municipal leaders' ideological orientations and the level of contracting out. Fernandez et al. (2008) observed that ideology did not account for the variation in contracting extent across U.S. local governments. Plata-Díaz et al. (2019) showed that ideology did not exert a strong influence on the choice to outsource social services among Spanish municipalities. In sum, the incongruent empirical findings, while underscoring the intricate nature of the ideology-contracting relationship, emphasize the need for a concerted effort to synthesize existing research findings. Therefore, we test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1.Jurisdictions with stronger right-wing ideological orientations engage more in contracting out.

Beyond investigating the overarching impact of political ideology on contracting out, our study delves into the nuances of this relationship by exploring potential moderating conditions. Guided by existing literature, our analysis focuses on five moderators: service type, ideology type, administrative tradition, time, and research design.

2.1 Service type

Within the government contracting literature, public services are typically divided into social services (“soft services”) and technical services (“hard services”) (e.g., Bel & Fageda, 2017; Foged, 2016; Hodge, 2018). Social services include areas like child welfare, elder care, job training, and mental health, while technical services include tasks such as public transit, road maintenance, and waste collection. Notably, social services are characterized by weaker market competition, more intricate outcome definitions, and heightened provider discretion (DeHoog & Salamon, 2002). These characteristics often result in higher transaction costs across various stages of the contracting process, including solicitation and negotiation (Brown & Potoski, 2003). Moreover, social service contracting can be prone to undesired contractor behaviors, including client selection and cheating (Bevan & Hood, 2006). Consequently, contracting typically leads to more efficiency gains in technical services when contrasted with social services (Hodge, 2018; Petersen et al., 2018).

Given the intricacies of social service contracting, the decision to opt for contracting out goes beyond operational consideration and becomes a challenging endeavor, often laden with political sensitivity and subject to ideological and partisan influences (Alonso & Andrews, 2020). For instance, Petersen et al. (2015) found that the choice to contract out social services in Danish municipalities was significantly influenced by the conservative ideology of the dominant party in the city council, a pattern less pronounced in decisions related to technical services. Similar observations emerged from Foged's (2016) study of Danish local governments and Alonso and Andrews' (2020) examination of English local governments. Building on this body of literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H2.The effect of right-wing ideology on contracting out is stronger in government contracting for social services than in government contracting for technical services.

2.2 Ideology type

The measurement of political ideology in a jurisdiction is a nuanced endeavor. In the government contracting literature, measures of political ideology can be largely categorized into two types: government ideology and citizen ideology (Bel & Fageda, 2009; Berry et al., 1998). The former captures the ideological orientation of elected officials or ruling parties, including measures such as the mayor's party affiliations and the dominating party in the legislature. The latter focuses on the ideological orientation of the electorate, including measures such as the percentage of votes for right-wing parties or candidates in elections. These two types of ideology measures capture different aspects of the political ideology of a jurisdiction and thus may have different impacts on government decision-making (Berry et al., 1998, 2010). Conceptually, government ideology has a more direct and immediate impact on policymaking than citizen ideology. Government ideology, reflecting the political orientation of ruling authorities, directly shapes policy preferences, priorities, and approaches. While citizen ideology is crucial in influencing government through the democratic process, its impact is indirect and mediated by electoral dynamics, as citizens express their preferences through voting, which then shapes policy decisions enacted by the government.

Research on government contracting decisions often focuses on one type of ideology measure, with only a handful incorporating both. Among these studies, the relative impact of government ideology and citizen ideology on contracting decisions remains mixed. For instance, Bel and Fageda (2008) found that Spanish municipalities with conservative mayors tend to privatize water and solid waste more frequently, regardless of the constituency's ideological orientation. In contrast, Elinder and Jordahl (2013) discovered a stronger effect of government ideology on contracting decisions among Swedish preschools and primary schools than citizen ideology. However, Alonso et al. (2016), incorporating both types of ideology, found no discernible difference in explaining contracting decisions in English local governments. Building upon this body of research, we continue to explore this relationship and test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H3.The effect of right-wing ideology on contracting out is stronger when using government ideology compared to citizen ideology.

2.3 Administrative tradition

The structure and behavior of public administration differ across countries. Painter and Peters (2010) and Peters (2021) introduced the administrative tradition framework as a means of comparing public bureaucracies. Administrative tradition, as Peters (2021, p. 23) defined it, refers to “a historically based set of values, structures, and relationships with other institutions that defines the nature of appropriate public administration within a society.” Within this context, Painter and Peters (2010) and Peters (2021) classified public administration traditions in developed Western democracies into four primary patterns: Anglo-American (e.g., Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States); Germanic (e.g., Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands); Napoleonic (e.g., France, Spain, and Italy); and Scandinavian (e.g., Denmark, Sweden, and Norway).

While each tradition exhibits distinct characteristics, the Anglo-American tradition diverges from others in a dimension relevant to the discourse on the ideology-contracting relationship. In the Anglo-American context, governance is marked by a prominent role for the market and civil society due to the relatively limited government involvement (Painter & Peters, 2010, p. 20). As a result, market-based ideas and pragmatic and incremental approaches have prevailed in the Anglo-American governance system. As Peters (2021, p. 136) wrote, compared with other traditions, “ideology plays a relatively minor role in Anglo-American politics, and perhaps even less in public administration.” Recent studies, including those by Warner and Aldag (2021) and Warner (2023), reinforce this perspective, illustrating that in the United States, a symbol of the Anglo-American tradition, contracting decisions are predominantly influenced by practical, market-driven considerations such as service cost, efficiency, and quality, rather than political interests. It underscored the Anglo-American tradition's disinclination to ideologically driven approaches in government contracting. Drawing from this rationale, our study seeks to test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H4.The effect of right-wing ideology on contracting out is weaker in the Anglo-American administrative tradition than in non-Anglo-American administrative traditions.

2.4 Time/year of data collection

As Gulick (1987, p. 115) emphasized, time is a critical factor in public administration, requiring acknowledgment that “organizational, managerial, economic, or social problems must be viewed as characteristics of a changing world.” The temporal dimension is crucial in comprehending the link between political ideology and government contracting decisions. An illustrative example is the rise of NPM and the increased adoption of contracting out—integral components of global government reform initiatives closely aligned with the political, economic, and social shifts of the 1980s and 1990s (Hood, 1991; Kettl, 2005; Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004). However, the dynamic nature of political, economic, and social landscapes suggests potential evolution over time. Beyond the NPM era, historical events, policy adjustments, and fluctuations in public sentiment represent just a subset of the multifaceted factors shaping the enduring impact of political ideology on contracting practices. This highlights the need to explore the temporal aspect in understanding how political ideology interacts with and shapes government contracting decisions.

Indeed, the dynamics of government contracting have been noted by scholars (e.g., Anguelov & Brunjes, 2023; Hefetz & Warner, 2004; Qian et al., 2022). For example, in Bel and Fageda's (2009), early meta-analysis of 32 studies on local government contracting, the researchers explored whether the influence of political ideology on local service contracting is moderated by the year of data collection, but they did not find a significant moderating effect. However, in Bel and Fageda's (2017, p. 503) review of more recent studies on local government contracting, they concluded that “ideological attitudes appear to be more influential than they seemed to be.” Building on these studies, we continue scrutinizing this temporal aspect of the relationship by exploring potential time trends. Given the competing observations in the literature, we test the following non-directional hypothesis:

Hypothesis H5.The effect of right-wing ideology on contracting out is moderated by the year of data collection.

2.5 Research design

A frequently employed methodology in the initial literature concerning government make-or-buy decisions involves multivariate analysis of a cross section of governments (e.g., Ferris, 1986; Girard et al., 2009; Ohlsson, 2003; Walls et al., 2005). However, this approach has been criticized by scholars for its methodological shortcomings that result in empirical outcomes with limited explanatory power (Bel & Fageda, 2007; Boyne, 1998a; Foged, 2016). One prominent limitation, underscored by Bel and Fageda (2009, p. 115), stems from the inherent cross-sectional nature of the data, where both the service delivery method and explanatory variables are observed at a single time point. This traditional approach often neglects the challenge of reverse causality (e.g., the service delivery method potentially influencing citizens' perceptions of the government's role), eroding the internal validity of the empirical conclusions.

In recent decades, research on government make-or-buy decisions has increasingly embraced a longitudinal framework (e.g., Alonso & Andrews, 2020; Foged, 2016; Plata-Díaz et al., 2019). By observing dependent and explanatory variables over an extended time span, longitudinal studies are better equipped to trace sequences of effects and uncover patterns of change, thereby offering enhanced insights into causality. Consequently, it is intriguing to investigate whether divergent findings emerge from cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, prompting the formulation of the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H6.The effect of right-wing ideology on contracting out estimated from longitudinal studies is different from that estimated from cross-sectional studies.

3 METHODS

We adopted a meta-analysis approach, a quantitative research synthesis technique, to comprehensively assess the effect of political ideology on contracting out. Meta-analysis, often referred to as an “analysis of analyses,” functions as a method for synthesizing statistical insights from a spectrum of original studies. It systematically collects and assesses the quantitative findings derived from these studies, culminating in the amalgamation of their results to establish a cumulative understanding across various research contexts (Glass, 1976). Through this process, scholars can derive a generalized effect between variables, illuminating overarching patterns, while also facilitating an exploration of how this effect might vary under specific circumstances. In our present study, we adhere to the meta-analysis framework developed by Ringquist (2013), tailored to suit the unique contexts of public administration research.

3.1 Literature search

- We conducted abstract searches on three prominent academic databases in the social sciences: Web of Science, EBSCO, and ProQuest, using the search query (ideolog*) AND (contract* OR privatiz*) AND (government* OR public).1

- We reviewed articles that included assessments of previous studies regarding government contracting decisions (Alonso & Andrews, 2020; Bel & Fageda, 2007; Bel & Warner, 2016; Boyne, 1998a) and identified relevant studies from their reference lists.

- We conducted a descendant search to uncover studies that referenced the original and influential work on contracting-out decisions. This backward-searching technique helps ensure the inclusion of relevant literature that has emerged after the initial research, enhancing the search's comprehensiveness and currency. We checked the Google Scholar citation counts of studies identified by other search strategies and focused on five studies on contracting-out decisions that were published relatively early and are highly cited (Bel & Fageda, 2007; Brown & Potoski, 2003; Ferris, 1986; Hefetz & Warner, 2004; Lopez-de-Silanes et al., 1997).2

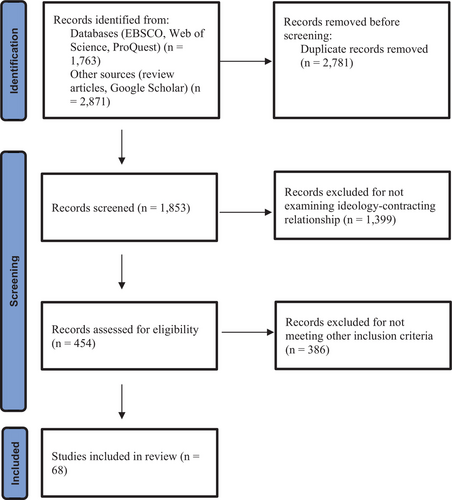

The culmination of these search strategies is visually outlined in the PRISMA flow diagram illustrated in Figure 1. Our literature search was finalized in mid-August 2022.

3.2 Selection criteria

- The study should concentrate on government organizations instead of business or nonprofit organizations.

- The study should quantitatively investigate the influence of political ideology on contracting out, using political ideology either as a key independent variable or as a control variable.

- The dependent variable, contracting out, refers to a government's engagement in the outsourcing of service delivery to third-party entities.3 Studies solely analyzing the consideration or planning of outsourcing (e.g., Chandler & Feuille, 1994; Girard et al., 2009) were excluded, as they differ from actual adoption. Similarly, articles on contracting back-in were omitted due to distinct driving factors (Clifton et al., 2021; Jansson et al., 2021; Lu & Hung, 2023). Studies concerning other government privatization mechanisms, such as franchises and municipal corporations, were excluded (e.g., Schmitt, 2014; Tavares & Camöes, 2007).

- The primary predictor, political ideology, is measured as the extent to which a jurisdiction is dominated by right-wing ideology.4 Studies relying on general measures of political sentiment favoring less government intervention or indirect demographic proxies (e.g., income, race) were excluded (e.g., Ferris, 1986; Hefetz & Warner, 2012; Stein, 1990), as they might not directly capture political ideology.

- Sufficient statistical data for effect size computation had to be present in the article. Studies lacking sufficient data for effect size calculation were excluded (e.g., Geys & Sørensen, 2016).

- The study was required to be reported in the English language.

Finally, we selected 68 studies for incorporation into our analysis. This compilation comprises 61 published journal articles and 7 unpublished sources (including 1 conference paper and 6 dissertations). These selected studies are highlighted in the references and described in Appendix 1.

Appendix 2 provides an overview of the diverse array of journals represented in our analysis. Notably, the journal articles include a wide spectrum of publication outlets, including traditional public administration journals such as Governance, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Public Administration, and Public Administration Review. Going beyond the boundaries of public administration, our analysis also encompasses journals from various social science fields, such as the European Journal of Political Economy, Journal of Public Economics, Public Choice, Social Science & Medicine, and Urban Affairs Review. This inclusive approach ensures a rich and multidimensional exploration of the subject matter, drawing insights from various academic perspectives and domains. Equally noteworthy is the temporal range of these articles, spanning from 1987 to 2021, affirming the enduring and compelling nature of scholarly exploration into government contracting decisions. In sum, the study of government contracting decisions has proven to be a persistent research topic, capturing the interest of scholars from diverse disciplinary backgrounds.

3.3 Sample description

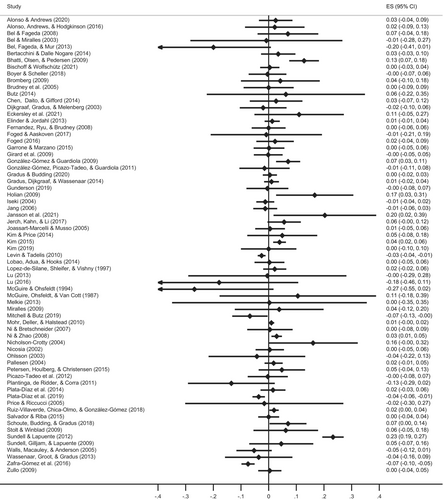

In meta-analyses, a key metric is the effect size, which quantifies standardized relationships between variables under investigation. Effect sizes are crucial for converting varied statistical findings into a unified scale, allowing for the synthesis and comparison of results across different studies. In our study, the focus is on effect sizes that quantify the standardized associations between right-wing ideology and the practice of contracting out. Considering that the studies included in our analysis predominantly employ regression analysis, we opted to use correlation-based effect sizes, specifically Pearson's r, to measure the associations as reported in the original research. This approach ensures consistency in quantifying these relationships across the studies. Following the recommendations by Ringquist (2013), 418 effect sizes were extracted from the 68 included studies (strategies used to calculate r-based effect sizes from original studies are explained in Appendix 3). These effect sizes, quantified using Pearson's r, exhibit a range from −0.46 to 0.48. Among this collection, 254 (60.77%) effect sizes signify a positive association, 131 (31.34%) a negative association, and 33 (7.89%) demonstrate a null association.

Figure 2 displays the distribution of these effect sizes, organized alphabetically based on the first author's last name, revealing substantial variability among existing studies in the ideology-contracting relationship. This visual representation effectively captures the wide array of conclusions drawn from these studies, underscoring the absence of a consistent consensus regarding the impact of political ideology on government contracting decisions. Taken together, all the descriptive information underscores the importance of ideology in government contracting research while also highlighting the inconclusive nature of existing literature. This emphasizes the significance of consolidating the overall effect and exploring the factors contributing to the conflicting results.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Average effect size analysis

Our initial step involved consolidating the effect sizes to compute an average effect size across all the included studies. During this process, we evaluated the heterogeneity of effect sizes to decide between employing a fixed- or random-effects model. The results of the Q test demonstrated that the effect size variability exceeded what can be attributed to sampling error (Q = 2308.86, p < 0.01). The I2 statistic indicated that a substantial 81.9% of the effect size variation cannot be explained solely by sampling error. Based on the outcomes of these two tests, we opted to employ a random-effects model. The calculated weighted average effect size in terms of Pearson's r is 0.017 (z = 5.96, p < 0.01), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.012, 0.023]. This result can be interpreted from two perspectives. First, the positive direction of the association signifies that a jurisdiction's right-wing ideological orientation positively influences the level of contracting out. Second, the strength of the correlation suggests that the effect is small. In sum, these findings provide support for H1.

4.2 Moderator analysis

Here, Yi represents the raw effect size from original study i, X1 pertains to service type (technical services = 1, social services = 2, general services = 3), X2 relates to ideology type (government ideology = 1, citizen ideology = 0), X3 signifies administrative tradition (Anglo-American tradition = 1, non-Anglo-American tradition = 0), X4 indicates the year of data collection (an average when multiple years were considered), X5 denotes research design (longitudinal analysis = 1, cross-sectional analysis = 0), and X6 represents publishing status (published = 1, unpublished = 0). Table 1 summarizes the distribution of these moderators in our sample and provides an overview of the average effect sizes in different circumstances.

| No. effect sizes | Q statistic | I2 statistic | Pearson's r | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 418 | 2308.86*** | 81.9% | 0.017*** | [0.012, 0.023] |

| Service type | |||||

| Technical services | 164 | 546.67*** | 72.9% | 0.008** | [0.001, 0.016] |

| Social services | 179 | 484.80*** | 63.3% | 0.039*** | [0.022, 0.056] |

| General services | 75 | 1191.87*** | 93.2% | 0.015*** | [0.007, 0.022] |

| Ideology type | |||||

| Citizen ideology | 183 | 427.89*** | 70.3% | 0.009*** | [0.003, 0.014] |

| Government ideology | 235 | 1868.06*** | 84.5% | 0.022*** | [0.012, 0.031] |

| Administrative tradition | |||||

| Anglo-American | 183 | 660.71*** | 72.5% | 0.005 | [−0.002, 0.012]] |

| Non-Anglo-American | 235 | 1626.21*** | 85.6% | 0.028*** | [0.019, 0.037] |

| Research design | |||||

| Cross-sectional | 224 | 565.03*** | 65.0% | 0.018*** | [0.010, 0.025] |

| Longitudinal | 194 | 1666.71*** | 87.4% | 0.015*** | [0.006, 0.023] |

| Publishing status | |||||

| Published | 325 | 1947.30*** | 83.8% | 0.020*** | [0.014, 0.027] |

| Unpublished | 93 | 283.15*** | 67.5% | 0.007 | [−0.005, 0.019] |

- * p < 0.1.

- ** p < 0.05.

- *** p < 0.01.

We used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) to formulate the meta-regression model, following the approach outlined by Ringquist (2013). The GEE method was selected to account for the presence of nonindependent observations in our dataset. By assigning reduced weight to effect sizes originating from studies with numerous effect sizes, this approach mitigates the potential dominance of a few studies in influencing the meta-regression outcomes. Table 2 presents the meta-regression results.

| Moderator | GEE model |

|---|---|

| Service type (technical services as reference group) | |

| Social services | 0.0428** (0.0197) |

| General services | 0.0159 (0.0168) |

| Ideology type (citizen ideology as reference group) | |

| Government ideology | 0.0164 (0.0183) |

| Administrative tradition (non-Anglo-American tradition as reference group) | |

| Anglo-American tradition | −0.0296** (0.0166) |

| Time | |

| Year of data collection | 0.0016 (0.0015) |

| Research design (cross-sectional analysis as reference group) | |

| Longitudinal | 0.0024 (0.0168) |

| Publication status | |

| Published | 0.0070 (0.0143) |

| Constant | −2.7333 (2.6686) |

| Number of effect sizes | 418 |

| Number of studies | 68 |

| Wald χ2 | 21.14*** |

- Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- * p < 0.1.

- ** p < 0.05.

- *** p < 0.01.

Among the 418 effect sizes analyzed, 39% are exclusively focused on technical services, 43% solely on social services,5 while 18% explore public services in general without focusing on a specific type (“general services”).6 The effect size for technical services exhibit a smaller average (r = 0.008, p < 0.05) in comparison to general services (r = 0.015, p < 0.01) and social services (r = 0.039, p < 0.01). To ascertain whether these discrepancies in average effect sizes hold statistical significance when considering other factors, a meta-regression approach was employed. The regression outcomes indicate that, on average, the effects for social services are significantly greater than those for technical services (p < 0.05). Consequently, service type emerges as a moderator in the ideology-contracting relationship, thereby providing corroborative evidence for H2. Collectively, these findings suggest that right-wing ideology influences government contracting decisions across various service types, although with varying degrees of impact. Particularly, decisions pertaining to contracting out social services exhibit a more pronounced ideological orientation than those concerning technical services.

In our analysis, we observed that 44% of the effect sizes under consideration are estimated using citizen ideology, whereas 56% use measures of government ideology. The estimates derived from government ideology tend to exhibit a higher average effect size (r = 0.022, p < 0.01) compared to those employing citizen ideology (r = 0.009, p < 0.01). To further assess the statistical significance of these differences and control for other pertinent factors, we conducted a meta-regression. The outcomes of the meta-regression suggest that while effect sizes using government ideology might trend higher, the distinction between the two groups of effect sizes is not statistically significant (p > 0.1). In other words, our findings do not support the idea that the type of political ideology significantly moderates the ideology-contracting relationship (H3). It appears that political ideology type may not play a substantial role in influencing the dynamics of the ideology-contracting relationship.

Within our sample, effect sizes from the Anglo-American tradition (44%) and non-Anglo-American tradition (56%) are roughly evenly distributed. The average effect size for the Anglo-American tradition (r = 0.005, p > 0.1) does not display statistical significance, indicating a lack of ideological effect. On the other hand, the average effect size for non-Anglo-American traditions (r = 0.028, p < 0.01) is notably robust, suggesting that ideology has a significant influence on shaping decisions regarding contracting out.7 We further examined these two sets of effect sizes within the meta-regression framework. The regression results validate the division between the Anglo-American and non-Anglo-American traditions (H4): the ideological relationship with contracting is statistically weaker on average in the Anglo-American tradition compared to non-Anglo-American traditions (p < 0.01), with other factors held constant. Put differently, ideology plays a relatively smaller role in explaining contracting out decisions within the Anglo-American tradition compared to other administrative traditions.

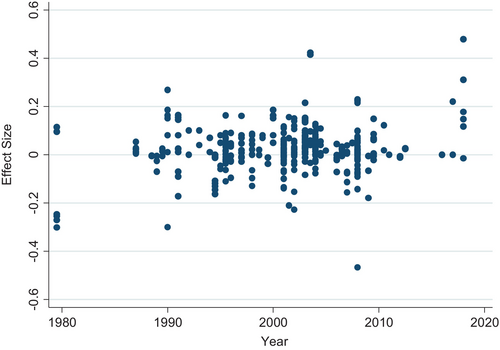

We delved into the dynamic relationship between ideology and contracting decisions over time. Initially, we used a scatterplot (Figure 3) to present all 418 effect sizes based on the years of data collection and elucidate the temporal trajectory of the ideological effect. The figure indicates no discernible temporal trend. To rigorously examine this, we further tested the moderating effect of time in the meta-regression framework. The regression results align with the visual finding: the moderator on the year of data collection is not statistically significant (p > 0.1), suggesting that time does not predict the variation in the effect size. In other words, we find no support for H5. Consequently, our findings indicate that the impact of ideology on government contracting decisions has not only endured but also maintained a consistent presence over the course of three decades.

Finally, in terms of research design, 54% of the effect sizes in our analysis are derived from cross-sectional analyses, while 46% stem from longitudinal analyses. The average effect size for cross-sectional studies (r = 0.018, p < 0.01) is marginally higher than that for longitudinal studies (r = 0.015, p < 0.01). Nevertheless, the meta-regression results fail to show support for the moderating effect of data structure (H6). Specifically, upon accounting for other influencing factors, the effects observed in cross-sectional studies do not exhibit a statistically significant difference from those observed in longitudinal studies (p > 0.1). Consequently, it becomes evident that data structure does not sufficiently account for the divergent findings present within the existing literature.

4.3 Publication bias

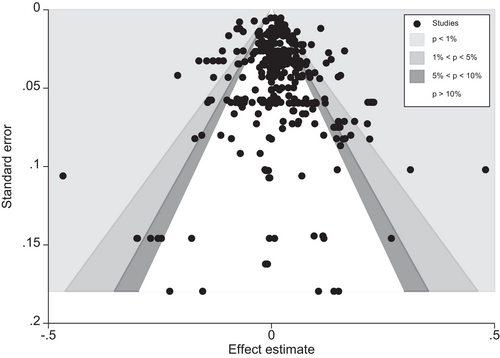

Publication bias, often referred to as the “file drawer problem,” has been recognized as a significant concern impacting the reliability of meta-analyses (Rothstein et al., 2006). Should unpublished findings substantially differ from those that are published, relying solely on the latter could lead to distorted estimations of the actual effect. Table 1 reveals that published studies exhibit a higher average effect size (r = 0.020, p < 0.01) compared to unpublished studies (r = 0.007, p > 0.1). Consequently, we took precautionary measures to investigate the possibility of publication bias from multiple angles (Ringquist, 2013). First, we conducted an extensive literature search to include gray literature, proactively minimizing the likelihood of bias. The final sample incorporated seven unpublished studies, comprising 93 effect sizes, which accounted for 22% of the total effect sizes analyzed. Second, to visually assess publication bias, we constructed a funnel plot. This an ex post treatment aims to identify any asymmetry in the plot that could arise from the suppression of smaller or nonsignificant studies. However, Figure 4 of the funnel plot does not exhibit conspicuous asymmetry indicative of substantial publication bias.

Third, we employed meta-regression as an additional post hoc technique to evaluate whether statistically significant distinctions exist between effect sizes derived from published and unpublished sources. The outcomes of the meta-regression did not offer evidence for the presence of publication bias. The moderator related to publication status did not demonstrate statistical significance at the 10% threshold, implying that the disparities between published and unpublished findings can be attributed to factors beyond their publication status. To summarize, the results from these analyses collectively indicate that the presence of publication bias is not a significant concern in our current analysis.

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence to assess the influence of political ideology on government contracting decisions. Despite the extensive examination within the government contracting literature, empirical findings have displayed notable inconsistency. Using a meta-analysis approach encompassing 418 effect sizes across 68 original studies, this investigation reveals that, on average, right-wing ideology exerts a modest yet positive influence on driving government contracting out. This finding contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical generalizations of the ideological impact across diverse circumstances. Additionally, it addresses a prominent concern discussed within the literature: whether “governments are guided by pragmatic rather than ideological motivations” in their contracting decisions (Bel & Fageda, 2007, p. 528). Our finding suggests that while the magnitude of the ideological effect may not be substantial, ideology still holds significance. Policymakers need to acknowledge the ideological dimensions at play, recognizing that the prevailing political climate can shape the choices made in contracting out public services. This awareness is crucial for developing contracting strategies that align with ideological stances, ensuring coherence between political beliefs and service delivery approaches.

In addition to the overarching effect, we contend that the ideological influence might be multifaceted and intricate, necessitating contextualization. In pursuit of this understanding, we incorporated moderator analysis to delve into the nuanced conditions shaping the ideology-contracting relationship. The insights from our moderator analysis contribute to the literature in meaningful ways.

To start, we explored whether the relationship between ideology and contracting differs between social and technical services, which inherently vary across dimensions like asset specificity and outcome measurability. Social services often involve labor-intensive tasks, heightened asset specificity, and relatively lower outcome measurability, potentially undermining the efficacy of contracting out and fostering political manipulation. Echoing Foged's (2016) concerns about the lack of service-specific explanations in government contracting research, we investigated the moderating role of service type, finding that ideology has a significantly more pronounced impact on social service contracting decisions compared to technical services. Our results substantiate that the drive to contract out for social services is notably ideologically motivated, aligning with earlier studies (e.g., Alonso & Andrews, 2020; Foged, 2016; Hefetz & Warner, 2012) and lending credence to the service-specific hypothesis articulated by Petersen, Houlberg, and Christensen (2015, p. 567) that “social services…emerge as contemporary arenas for ideological debates regarding public or private service delivery.” This finding also emphasizes the practical imperative of being cognizant of the pronounced ideological influence in social service contracting decisions and navigating the ideological landscape in contracting implementation.

Second, while the existing body of contracting studies often integrates government ideology and/or citizen ideology in their analyses, the nuanced examination of how these two types of ideologies may differ in influencing government contracting decisions remains a less-explored area, yielding inconclusive evidence. Our meta-regression provides an opportunity to delve into this nuanced comparison. The finding that citizen ideology and government ideology do not exhibit significant differences in their impact on government contracting decisions holds substantial implications. It suggests that, in the context of government contracting, the source of ideological influence—whether emanating from the electorate or the ruling authorities—may not be a critical factor in determining outcomes. This finding challenges prior assumptions regarding the dominance of either citizen or government ideology in steering government contracting decisions. Additionally, it implies that policymakers should adopt a holistic view of a jurisdiction's ideological landscape when analyzing and devising government contracting strategies, recognizing that both citizen and government ideologies contribute meaningfully to the decision-making process.

Third, employing the administrative tradition perspective, we scrutinized the ideology-contracting relationship across traditions, revealing a divide between Anglo-American and non-Anglo-American contexts. In Anglo-American settings, political ideology has a limited role in shaping contracting decisions, while it significantly influences non-Anglo-American traditions. Our findings suggest a pronounced inclination toward ideologically driven contracting in non-Anglo-American countries compared to their Anglo-American counterparts, reflecting the prominence of market-oriented ideas in the latter. This aligns with recent studies on contracting back-in, where the United States predominantly supports pragmatic market management (Kim & Warner, 2016; Warner, 2023; Warner & Aldag, 2021), while non-Anglo-American countries often view re-municipalization as a politically transformative movement (Albalate & Bel, 2021; Campos-Alba et al., 2017; Gradus & Budding, 2020). Our study builds upon observations of institutional differences in government contracting research, asserting that administrative tradition moderates the ideology-contracting relationship. As Warner and Bel (2008, p. 733) highlighted, “differences in national traditions of public intervention, institutional arrangements, and municipal environments make local public services an area of great diversity.” This insight holds the potential to inform future comparative research in government contracting.

Fourth, in our examination of the temporal dimension in the influence of political ideology on government contracting decisions, we aimed to scrutinize potential variations or trends over the years amid the evolving socio-political landscape. While the literature acknowledges the dynamics of the government contracting process, the exploration of whether and how the ideological effect changes over time is underexplored. Drawing from Bel and Fageda's (2009) early meta-analysis, our results align, depicting a remarkably stable effect across periods, emphasizing the enduring influence of political ideology on government contracting decisions over four decades. This relationship advances our understanding of ideological influences, deepening findings and offering insights for policymakers and practitioners. Recognizing the persistent importance of political ideology in shaping decision-making, our research underscores enduring relevance, urging nuanced understanding beyond contemporary contexts. Navigating these temporal dynamics, our study unveils a narrative transcending individual instances, offering a holistic perspective within the broader historical and social context of government contracting.

Fifth, we delved into the potential influence of data structure on the ideology-contracting relationship. Early government contracting research was not immune to criticism for methodological limitations (Bel & Fageda, 2007; Boyne, 1998b). A notable critique centers around the insufficient rigor of cross-sectional designs, which might struggle to discern the timing of government make-or-buy decisions and their precursors, thus leaving the specter of reverse causality unaddressed. Recognizing the growing preference for longitudinal approaches in recent studies, we undertook a comparison between the results of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Our analyses indicate that there is no statistically significant difference between these two types of studies regarding the ideology-contracting relationship. Consequently, it appears that data structure per se does not significantly moderate this relationship.

Nonetheless, it is important to recognize that our finding does not negate the importance of research design; rather, data structure constitutes just one facet of research design. For instance, an additional concern in government contracting research, highlighted by scholars, pertains to the prevalence of observational designs, which might prove less robust in addressing threats from unobserved variables, particularly endogenous ones. A number of recent studies have attempted to address this methodological concern by employing quasi-experimental designs like difference-in-differences and regression discontinuity (e.g., Alonso & Andrews, 2020; Foged, 2016; Jerch et al., 2017).8 Regrettably, the relatively small number of effect sizes stemming from these quasi-experimental studies precluded us from conducting a meaningful regression analysis to assess whether observational and quasi-experimental designs indeed yield divergent outcomes. Hence, the scope to explore whether enhanced research designs yield more conclusive results remains an avenue for future inquiry.

It is imperative to recognize that the present study carries additional limitations, which offer insights for future research. First, as mentioned earlier, while a small subset of quasi-experimental studies exists, the predominant portion of studies included in this meta-analysis adopts an observational approach. Consequently, our meta-analysis findings are most appropriately interpreted as demonstrating associations rather than implying causal relationships. Second, the array of moderators incorporated into the meta-regression is confined to those widely featured in existing studies and is by no means exhaustive. Several potential moderators have been proposed in various studies but were excluded from our current analysis due to data constraints. For example, it would be intriguing to dissect the moderating effect of contractor type (e.g., for-profit vendors versus nonprofit vendors) (Eckersley et al., 2021). Additionally, delving into whether ideology wields a stronger or weaker impact on contracting out under the backdrop of challenging fiscal conditions could yield interesting insights (Pallesen, 2004; Plata-Díaz et al., 2019).

Third, while we strive to conduct a comprehensive literature search to identify relevant studies, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations inherent in this process. For example, our search focuses on studies written in English, which may inadvertently exclude non-English studies in countries where government contracting is also prevalent. Consequently, it is crucial to recognize that, due to these considerations, our literature search may not exhaust every existing study pertaining to the relationship under study. The findings should be interpreted within the context of these limitations. Fourth, the included studies mainly focus on local and state government contracting, probably because there are more available data and variations at this level. However, the limited representation of federal government contracting (only one study included) may constrain generalizability to the federal level. This highlights an opportunity for future research to conduct more comprehensive investigations at the federal level, contributing to a broader understanding of government contracting decisions across administrative tiers.

In conclusion, our study leveraged decades of empirical evidence to examine the intricate role of political ideology in shaping government contracting decisions. The results affirm that ideology stands as an enduring and relevant factor in these decisions, albeit with nuanced variations under specific circumstances. Our contribution lies in the systematic synthesis of disparate findings, resolution of empirical inconsistencies, and exploration of contextual variations. These findings not only offer valuable insights but also lay a robust foundation for continued exploration and refinement of our understanding of government contracting dynamics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Endnotes

APPENDIX 1: CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES IN THE META-ANALYSIS

| # | Study | Country | Government level | Administrative tradition | Data years | Sample size | Contracting measure | Ideology measure | Contracted service | Service type | Analytical method | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alonso and Andrews (2020) | U.K. | Local | Anglo-American | 2009–2016 | 2379 | Dummy | Percent of council seats | Child services | Social services | Regression discontinuity | Journal article |

| 2 | Alonso et al. (2016) | U.K. | Local | Anglo-American | 2007 | 335 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy), Percentage of voters | Leisure services | Social services | Spatial auto-regressive probit | Journal article |

| 3 | Bel and Fageda (2008) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2003 | 1085 | Dummy | Mayor's party affiliation (dummy), Percentage of right-wing voters | Water services, Waste collection | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 4 | Bel and Miralles (2003) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1979–1998 | 90 | Dummy | Conservative ruling party (dummy) | Waste collection | Technical services | Probit | Journal article |

| 5 | Bel et al. (2013) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2008 | 92 | Dummy | Mayor's party affiliation (dummy) | Waste collection | Technical services | Probit | Journal article |

| 6 | Bertacchini and Dalle Nogare (2014) | Italy | Local | Napoleonic | 1998–2008 | 1111 | Percentage and Per capita of expenditure contracted | Government ideology index | Culture services | Social services | Dynamic panel analysis | Journal article |

| 7 | Bhatti et al. (2009) | Denmark | Local | Scandinavian | 2002–2006 | 1333 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Mayor's party affiliation (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

| 8 | Bischoff and Wolfschuetz (2021) | Germany | Local | Germanic | 2001–2015 | 3213 | Dummy | Percentage of council seats | Administrative services | Social services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 9 | Boyer and Scheller (2018) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2000–2016 | 850 | Dummy | Government ideology index | Infrastructure facilities | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 10 | Bromberg (2009) | USA | Federal | Anglo-American | 2001–2006 | 192 | Percentage budget contracted | Percentage of Republicans in legislature | General public services | General services | OLS | Doctoral dissertation |

| 11 | Brudney et al. (2005) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1998 | 472 | Percentage of budget contracted | Government ideology index, Citizen ideology index | General public services | General services | Hierarchical linear modeling | Journal article |

| 12 | Butz (2014) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2001 | 50 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Government ideology index, Governor's party affiliation | Human services | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 13 | Chen et al. (2014) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1998–2010 | 624 | Dummy | Governor's party affiliation, Majority party in legislature | Infrastructure facilities | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 14 | Dijkgraaf et al. (2003) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 1998 | 540 | Dummy | Percentage of votes | Waste collection | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 15 | Eckersley et al. (2021) | UK | Local | Anglo-American | 2015–2019 | 150 | Number of contracts awarded | Ruling party (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

| 16 | Elinder and Jordahl (2013) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 1998–2006 | 5128 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Right-wing ruling party (dummy), Percentage of right-wing voters | Education | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 17 | Fernandez et al. (2008) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2002 | 1026 | Number of services contracted | Ratio of Democrats to Republicans in legislature | General public services | General services | Hierarchical linear modeling | Journal article |

| 18 | Foged (2016) | Denmark | Local | Scandinavian | 2004–2012 | 855 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Percentage of left-wing mandates | A range of different services | Technical and Social services | Difference-in-differences | Journal article |

| 19 | Foged and Aaskoven (2017) | Denmark | Local | Scandinavian | 2012 | 98 | Percentage of services contracted | Percentage of left-wing mandates | Elder care | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 20 | Garrone and Marzano (2015) | Italy | Local | Napoleonic | 2001–2012 | 1243 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Gas services | Technical services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 21 | Girard et al. (2009) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2004 | 1422 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican voters | General public services | General services | Logit | Journal article |

| 22 | González-Gómez and Guardiola (2009) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1985–2006 | 2021 | Dummy | Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 23 | González-Gómez et al. (2011) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1985–2006 | 741 | Dummy | Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Discrete choice model | Journal article |

| 24 | Gradus and Budding (2020) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 1999–2014 | 5962 | Dummy | Percentage of council seats | Waste collection | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 25 | Gradus et al. (2014) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 1998–2010 | 5349 | Dummy | Percentage of party voters | Waste collection | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 26 | Gunderson (2019) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1986–2016 | 1417 | Dummy, Number of inmates in private facilities | Governor's party affiliation (dummy), Majority party in legislature (dummy) | Prisons | Social services | OLS, Survival analysis | Doctoral dissertation |

| 27 | Holian (2009) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1990, 2000 | 200 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican voters | Emergency services | Social services | Probit | Journal article |

| 28 | Iseki (2004) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1992–2000 | 3649 | Dummy | Percentage of democratic seats/votes | Public transit | Technical services | Multinomial logit | Doctoral dissertation |

| 29 | Jang (2006) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2002–2007 | 4460 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican voters | A range of different services | Technical and Social services | Probit | Doctoral dissertation |

| 30 | Jansson et al. (2021) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 2018 | 290 | Frequency of contracting | Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

| 31 | Jerch et al. (2017) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1998–2011 | 1965 | Percentage of services contracted | Mayor's party affiliation (dummy) | Public transit | Technical services | Regression discontinuity | Journal article |

| 32 | Joassart-Marcelli and Musso (2005) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1982–1997 | 1333 | Dummy | Democrat-Republican voters ratio | General public services | General services | Multinomial logit | Journal article |

| 33 | Kim (2015) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1993–2009 | 7089 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Percentage of Democratic voters | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

| 34 | Kim (2019) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2016 | 387 | Frequency of contracting | Governor's party affiliation (dummy), Majority party in legislature (dummy) | Human services | Social services | Ordered logit model | Journal article |

| 35 | Kim and Price (2014) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1999–2006 | 244 | Percentage of inmates in private facilities | Government ideology index | Prisons | Social services | Generalized estimating equation | Journal article |

| 36 | Levin and Tadelis (2010) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1997, 2002 | 19,244 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican voters | General public services | General services | Multinomial logit | Journal article |

| 37 | Lobao et al. (2014) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2001–2008 | 1756 | Dummy, Percentage of services contracted | Percentage of Republican voters | General public services | General services | OLS, Logit | Journal article |

| 38 | Lopez-de-Silanes et al. (1997) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1987–1992 | 36,504 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican voters | A range of different services | Technical and Social services | Probit, OLS, Multinomial logit | Journal article |

| 39 | Lu (2013) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2009 | 50 | Number of contracts | Government ideology index | Human services | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 40 | Lu (2016) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2009 | 50 | Number of contracts | Government ideology index | Human services | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 41 | McGuire and Ohsfeldt (1994) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1979–1980 | 51 | Percentage of services contracted | Government ideology index | School bus | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 42 | McGuire et al. (1987) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1979–1980 | 51 | Percentage of services contracted | Government ideology index | School bus | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 43 | Melkie (2013) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2002 | 34 | Percentage of services contracted | Government ideology index, Governor's party affiliation (dummy), Majority party in legislature (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Doctoral dissertation |

| 44 | Miralles (2009) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1980–2002 | 513 | Dummy | Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Log–log | Journal article |

| 45 | Mitchell and Butz (2019) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1979–2010 | 943 | Dummy | Citizen ideology index, Dominating party in legislature (dummy) | Prisons | Social services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 46 | Mohr et al. (2010) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1995, 1997, 2004–2005 | 36,605 | Dummy | Percentage of Republican votes | General public services | General services | Logit | Journal article |

| 47 | Ni and Bretschneider (2007) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 2001–2002 | 573 | Dummy | Percentage of Republicans in legislatures, Republican governor (dummy) | E-government services | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 48 | Ni and Zhao (2008) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 2000–2006 | 10,661 | Dummy | Ratio of Democrat to Republican voters | General public services | General services | Logit | Journal article |

| 49 | Nicholson-Crotty (2004) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1996–1998 | 150 | Dummy | Citizen ideology index | Prisons | Social services | Logit | Journal article |

| 50 | Nicosia (2002) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1993–1998 | 1457 | Dummy | Percentage of Democrats in legislatures, Democratic governor (dummy) | Public transit | Technical services | OLS, Logit | Doctoral dissertation |

| 51 | Ohlsson (2003) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 1989 | 170 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Waste collection | Technical services | Probit | Journal article |

| 52 | Pallesen (2004) | Denmark | Local | Scandinavian | 1985–1997 | 3575 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Mayor's party affiliation (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

| 53 | Petersen et al. (2015) | Denmark | Local | Scandinavian | 2007–2012 | 549 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Percentage of socialist seats | A range of different services | Technical and Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 54 | Picazo-Tadeo et al. (2012) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1986–2006 | 734 | Dummy | Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Probit | Journal article |

| 55 | Plantinga et al. (2011) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 2006–2008 | 159 | Percentage of in-house expenditure | Percentage of left-wing voters | Employment services | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 56 | Plata-Díaz et al. (2014) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2002–2010 | 3912 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Waste collection | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 57 | Plata-Díaz et al. (2019) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2000–2012 | 20,796 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Social services | Social services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 58 | Price and Riccucci (2005) | USA | State | Anglo-American | 1990 | 50 | Percentage of private prison beds | Citizen ideology index, Governor's party affiliation | Prisons | Social services | OLS | Journal article |

| 59 | Ruiz-Villaverde et al. (2018) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 1995–2013 | 13,590 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Logit | Journal article |

| 60 | Salvador and Riba (2015) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2011 | 2680 | Dummy | Government ideology index | General public services | General services | Logit | Journal article |

| 61 | Schoute et al. (2018) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 2010–2011 | 868 | Dummy | Government ideology index | General public services | General services | Multinomial logit | Journal article |

| 62 | Stolt and Winblad (2009) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 1990–2003 | 285 | Percentage of contracted employment | Percentage of parliament members | Elder care | Social services | Projection to latent structures | Journal article |

| 63 | Sundell and Lapuente (2012) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 1999–2008 | 2583 | Percentage of expenditure contracted | Government ideology index | General public services | General services | OLS, Fixed effects vector decomposition | Journal article |

| 64 | Sundell et al. (2009) | Sweden | Local | Scandinavian | 2008 | 290 | Percentage of services contracted | Government ideology index, Right-wing ruling party (dummy) | General public services | General services | OLS | Conference paper |

| 65 | Walls et al. (2005) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1995 | 980 | Dummy | Percentage of Democrat voters | Waste collection | Technical services | Multinomial logit | Journal article |

| 66 | Wassenaar et al. (2013) | Netherlands | Local | Germanic | 2009 | 262 | Dummy | Relative number of left-wing aldermen | General public services | General services | Logit | Journal article |

| 67 | Zafra-Gómez et al. (2016) | Spain | Local | Napoleonic | 2002–2012 | 6803 | Dummy | Left-wing ruling party (dummy) | Water services | Technical services | Survival analysis | Journal article |

| 68 | Zullo (2009) | USA | Local | Anglo-American | 1992–2002 | 2183 | Percentage of services contracted | Percentage of Republican voters | General public services | General services | OLS | Journal article |

APPENDIX 2: DISTRIBUTION OF STUDIES BY JOURNAL

| Journal | No. articles included |

|---|---|

| Administration & Society | 2 |

| Economics Letters | 1 |

| Empirical Economics | 1 |

| European Journal of Political Economy | 2 |

| Financial Accountability & Management | 1 |

| Fiscal Studies | 1 |

| Governance | 3 |

| International Journal of Public Administration | 1 |

| International Public Management Journal | 2 |

| Journal of Economic Policy Reform | 1 |

| Journal of Policy Practice | 1 |

| Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory | 2 |

| Journal of Public Economics | 1 |

| Journal of the Transportation Research Forum | 1 |

| Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis | 1 |

| Local Government Studies | 4 |

| Municipal Financial Journal | 1 |

| Policy Studies Journal | 1 |

| Politics & Policy | 1 |

| Public Administration | 2 |

| Public Administration Review | 4 |

| Public Administration Quarterly | 1 |

| Public Budgeting & Finance | 1 |

| Public Choice | 4 |

| Public Management Review | 1 |

| Public Organization Review | 1 |

| Public Works Management & Policy | 1 |

| Revista de Economía Aplicada | 1 |

| Social Policy & Administration | 1 |

| Social Problems | 1 |

| Social Science & Medicine | 1 |

| The American Review of Public Administration | 2 |

| The Journal of Industrial Economics | 1 |

| The RAND Journal of Economics | 1 |

| Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences | 1 |

| Urban Affairs Review | 6 |

| Urban Studies | 1 |

| Urban Water Journal | 1 |

| Waste Management | 1 |

APPENDIX 3: EFFECT SIZE CALCULATION

- In the majority of instances, r-based effect sizes were directly computed from regression estimators, including regression coefficients, standardized regression coefficients, t-scores, and z-scores. For example, when a t score was available, the partial correlation coefficient was calculated based on the formula: .

- When original studies reported odds ratios (e.g., Boyer & Scheller, 2018; Plata-Díaz et al., 2014), odds-based effect sizes were initially calculated and subsequently transformed into r-based effect sizes.

- If original studies reported multiple effect sizes due to various independent samples or differing variable measures (e.g., Bel & Fageda, 2008; Gunderson, 2019; Petersen et al., 2015), all pertinent effect sizes from each sample were recorded to preserve within-study variation.

- In instances where original studies presented parameter estimates alongside asterisks indicating statistical significance levels (e.g., Gradus et al., 2014; Ruiz-Villaverde et al., 2018), t-scores or z-scores were approximated based on the indicated symbols, and subsequently transformed into correlation-based effect sizes. In such cases, the derived effect sizes serve as conservative lower bound estimates.

- When original studies solely reported nonsignificant parameters of interest (e.g., Brudney et al., 2005; Gradus et al., 2014), the corresponding effect sizes were set to 0. Here, the calculated effect sizes also serve as lower bound estimates.

- Following the computation of r-based effect sizes, all effect sizes were then converted into Fisher's z correlations. This conversion serves to address the minor bias associated with Pearson's r. Such transformation aids in normalizing effect sizes and correcting the skewed distribution of Pearson's r in relation to a given population.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.