Managing crises as if no one is watching? Governance dilemmas from a public perspective

Abstract

In the midst of ongoing crises, understanding how citizens perceive administrative crisis management is more relevant than ever. Combining organizational literature with insights from legitimacy research, this article scrutinizes how the public evaluates governance decisions concerning prominent crisis management dilemmas: flexibility versus stability, inclusion versus exclusion, and equity-based versus needs-based resource distribution. The paper argues that flexible, inclusive, and equity-based governance decisions are generally perceived as more legitimate. However, governance decisions are also associated with adverse effects that can mitigate any initially positive effect on legitimacy. The argument is tested in a large-scale randomized survey experiment in the context of a migration crisis, where governance decisions were manipulated. The findings support the expectations for inclusive crisis management and equity-based resource distribution, which are perceived as the most legitimate governance alternatives. Internal adaptations of administrative practices toward more flexible and adaptive solutions, however, are perceived less legitimate than stable governmental action.

1 INTRODUCTION

Crisis situations pose extreme governance challenges for governments and public administrations. To respond to the urgency and uncertainty of crises, governments and public administrations must move away from routine actions and instead find alternative coping strategies to deal with the situation and fulfill their system-maintaining role. Therefore, administrations mix or replace established bureaucratic routines with new procedures to become adaptive, flexible, and inclusive (Ansell & Boin, 2019; Eckhard et al., 2021; Jung et al., 2018; Moon, 2020). However, this process of deviating from routine behavior is particularly susceptible to the emergence of governance dilemmas, namely situations in which each competing governance alternative is associated with clear advantages and disadvantages, where an inherent contradiction between two alternatives exists and organizations need to prioritize one over the other (Carlson et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2007; Seo & Creed, 2002; Smith & Lewis, 2011). A recent and prominent example are the mask procurement scandals that occurred throughout the Covid-19 Pandemic, when many countries loosened procurement regulations to provide room for maneuvering but simultaneously paved the way for abuse and personal enrichment (Fütterer-Akili, 2022). The question of how to successfully decide on government alternatives over others, is therefore a central component of organizational and crisis research.

Conversely, it is worth noting that entrenched bureaucratic routines, while potentially constraining internal crisis management capabilities, serve as vital pillars of political legitimacy by ensuring legality, transparency, and accountability (Stark, 2010). As such, public administrations play a supporting role for democracy, fostering political and institutional trust and legitimacy (Bogumil & Kuhlmann, 2015; Deephouse et al., 2017; Herian et al., 2012). Considering the relevance of bureaucratic procedures for legitimacy, it is crucial to understand how governance decisions, and hence the government process, affect public perceptions of legitimacy. So far, the existing research on the topic mostly focuses on crisis management performance and outcomes, and hence output legitimacy (Christensen et al., 2011; Mizrahi et al., 2021b). In contrast, this article aims at understanding the effects of the governance process, and in particular specific governance alternatives, on public legitimacy. The central research question of this article thus asks what effect the administration's decisions on resolving governance dilemmas have on the public legitimacy of crisis management.

To investigate to which extent the various manifestations of crisis management impact the degree of crisis management legitimacy, the paper looks at three prominent governance dilemmas in crisis management with opposing alternative governance options: (1) flexibility versus stability in the organizational reaction (Webb & Chevreau, 2006), (2) inclusion versus exclusion regarding external actors (Moynihan, 2009; Whittaker et al., 2015), and (3) equality versus needs-based resource redistribution among different recipients (Henstra, 2010; Sutter & Smith, 2017). Public administrations are inevitably exposed to the tensions between competing alternatives when responding to crises. Depending on how administrations choose to solve existing governance dilemmas, various manifestations of crisis management can emerge. Prior research gives some indication that certain governance alternatives are assessed more positively than others (Lakoma, 2024). For example, the results of Lenz (2022) show that citizens who volunteered during the 2015/16 migration crisis recorded an increase in trust in the administration if they perceived the administration as a flexible and inclusive actor. Participation is also a driver of legitimacy and is positively associated with citizen satisfaction (e.g., Laegreid & Rykkja, 2015; Wu & Jung, 2016).

The effects of governance alternatives on public legitimacy are tested in a preregistered survey-experiment conducted among 2.630 participants of a probability population in Germany. A set of vignettes that describe hypothetical crisis management scenarios are used to manipulate the governance alternatives. The different manipulations encompass descriptions of either the routine approach, bureaucratic adaptation, or a rampant scenario characterized by adverse manifestations of adaptation. The findings show that citizens perceive crisis management as more legitimate when administrations react stable instead of flexible and inclusive instead of exclusive. The differences between needs-based and equality-based resource redistribution were small but lean toward the equality-based redistribution. Particularly, the finding that flexible crisis management, while increasing internal effectiveness, decreases perceived legitimacy levels, emphasizes the need to put public perceptions more into focus in crisis management and public administration theory.

The paper makes several contributions: First, it contributes to existent literature by combining crisis management and organizational research with approaches from legitimacy research. Moreover, by featuring crisis management dilemmas, the paper adds a perspective on the crisis management process rather than its outcome. It aims at understanding how specific ways of dealing with dilemmas relate to public evaluations. Second, the paper contributes experimental evidence and original data on how the public evaluates government responses to crises. Finally, emphasizing the legitimacy of crisis management holds essential insights for crisis management practitioners: It can encourage crisis managers to engage not only with an organizational perspective on crisis management success but also consider the public legitimacy of the process. This way, the findings hold implications for dealing with crisis management dilemmas by emphasizing legitimacy considerations.

The article is structured as follows: The next section defines crisis management legitimacy and theorizes on the relationship between legitimacy perceptions and crisis management dilemmas. Next, the case of the German migration crisis 2015/2016 is introduced and the underlying data and design of the survey experiment are laid out. The presentation of the results of the analysis is followed by a discussion of the limitations of the study and concluding remarks.

2 THE EXTERNAL LEGITIMACY OF CRISIS MANAGEMENT

Governance legitimacy is a well-explored phenomenon in political and organizational science. Legitimacy is commonly defined as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate” (Suchman, 1995, p. 574). This concept hinges on the perceptions, sentiments, and visibility of various government and administrative behaviors. It encompasses not just what the government does but also how citizens expect it to behave and how they assess its actions (Christensen et al., 2016; Scharpf, 1999; V. Schmidt, 2013; Suchman, 1995). In essence, legitimacy embodies the relationship between a government and its citizens, including their assessments of administrative or governance processes. These assessments cover factors such as responsiveness, inclusiveness, transparency, fairness, accountability, and impartiality (Bovens, 2007; Herian et al., 2012). Within the context of legitimacy research, literature differentiates between input, throughput, and output legitimacy. Input legitimacy pertains to politics and the quality of political representation and responsiveness. Output legitimacy relates to the effectiveness, decisions, and policies resulting from the political process. Meanwhile, throughput legitimacy relates to the governance process as such and focuses on the degree of accountability and transparency of actors and their practices, as well as their openness to civil society groups (Easton, 1967; Scharpf, 1999; V. Schmidt, 2013; V. Schmidt & Wood, 2019).

Additionally, in organizational institutionalism, there is the notion of responding to challenges of legitimacy (Deephouse et al., 2017). When faced with inconsistent criteria, organizations grapple with managing their legitimacy. To either gain or maintain legitimacy, organizations can extend their existing legitimacy to encompass new activities. However, in some cases, they may need to engage in renegotiation, decoupling, or adaption to new situations and uncertainties (Deephouse et al., 2017; Smith & Besharov, 2019). It is, however, crucial to note that different sources of legitimacy may have conflicting criteria at times. Public administrations, in particular, face difficulties in this type of organizational adaptation. These entities are primarily designed to function within established routines, prioritizing the maintenance of legality, transparency, and accountability, and thereby upholding essential components of process legitimacy (Peters, 2001; Weber, 2002). This undermines the complex interplay between organizations, their broader sociocultural milieu, and the unique challenges to legitimacy posed by crises (Stark, 2010, 2014).

Thus far, our understanding of the relationship between crisis governance and public perceptions of legitimacy remains somewhat limited. Only few studies have investigated citizens' perceptions of government performance and effectiveness in this context (Christensen et al., 2011; Mizrahi et al., 2021b). Their findings underscore the importance of immediate results, like readiness and preparedness, as well as traits such as responsiveness and transparency, in shaping how citizens perceive crisis management overall. Other studies suggest that certain aspects of crisis management, like the distribution of help or blame attribution, can affect electoral support and outcomes (e.g., Bechtel & Hainmueller, 2011; Malhotra & Kuo, 2008). Mazepus and van Leeuwen (2019) explored the relationship between crisis management and legitimacy in the context of natural disasters. Their research showed that equitable resource allocation and fair procedural practices play a significant role in influencing citizen perceptions and preferences. These findings provide important indications of how citizens evaluate the legitimacy of government actions during crisis management. Considering that the process itself seems to be as important as the outcomes in garnering public support for administrative actions (Van Ryzin, 2011; Vigoda-Gadot & Mizrahi, 2016), it is important to further scrutinize the determinants of public legitimacy during the crisis management process. By investigating how organizational dilemmas are evaluated from the perspective of public legitimacy, this article aims at further addressing this research gap.

3 CRISIS GOVERNANCE AND DILEMMAS

Crisis management research primarily focuses on organizational, technical, or managerial perspectives, as well as procedural features and the use of resources. Within crisis research, the central questions revolve around structures, routines, coordination mechanisms, and the overall effectiveness of crisis management strategies (Ansell et al., 2010; Nohrstedt et al., 2018). However, there is no ideal operating mode for crisis management due to governance dilemmas and trade-offs that evolve under the uncertainty of crises (Moynihan, 2009; Rosenthal et al., 2001; A. Schmidt, 2019; Webb & Chevreau, 2006). Governance dilemmas, because of their paradoxical nature, cannot be readily resolved through clever organization and good management alone (Lewis & Smith, 2014; Rivera & Knox, 2023; A. Schmidt, 2019). Instead, these dilemmas entail situations characterized by a challenging choice among options, each carrying both advantages and disadvantages, and lacking an ideal or fully satisfying solution. Consequently, decision-making in crisis contexts necessitates consideration of trade-offs, where decision-makers consciously opt for certain benefits while reluctantly sacrificing others (Carlson et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2007; Seo & Creed, 2002; Smith & Lewis, 2011)—a nuanced process made more complex by the pressures of crisis-induced uncertainty and urgency. This dynamic is particularly salient in transboundary crises, where a multiplicity of actors, sectors, institutions, and divergent opinions, give rise to governance dilemmas. Moreover, within highly politicized contexts, such as those surrounding issues like migration or recent pandemics, the prominence of governance dilemmas potentially increases (Carlson et al., 2017; Christensen et al., 2016; Lewis & Smith, 2014; Mazepus & van Leeuwen, 2019; Smith & Lewis, 2011).

The three dilemmas discussed in this article are selected considering their omnipresence in crisis management research1 but also because of their connection to legitimacy, as the governance alternatives they encompass have a direct bearing on the legitimacy of the crisis management process. First, the internal flexibility versus stability dilemma addresses the question of transparency and legality relevant for throughput legitimacy (Comfort, 2007; Deverell, 2010; Webb & Chevreau, 2006). Second, the external inclusion versus exclusion dilemma speaks to the aspect of openness and inclusion in the governance process (Iusmen & Boswell, 2017; McLennan et al., 2021; Moynihan, 2009; Whittaker et al., 2015); and finally, fairness is addressed by the resource dilemma, that is concerned with the resource reallocation based on equity or need between recipients (Rosenthal et al., 2001; Sutter & Smith, 2017). All three dilemmas are central to internal crisis management performance. They have been studied extensively in organization theory and public administration research, but not from a legitimacy perspective.

Considering this context, it is reasonable to expect that the governance choices made by crisis managers in addressing these dilemmas will lead to different effects on the perceived degree of public legitimacy. When crisis management leans toward one alternative or another, the negative aspects of the alternative may not immediately surface or be seen as equally relevant. Prior research offers some insights, indicating that certain governance alternatives tend to receive more favorable assessments than others: Flexibility and inclusion have been found to be positively associated with citizen trust (e.g., Lenz, 2022; Mizrahi et al., 2021a; Wu & Jung, 2016). Similar observations can be made for the resource dilemma, where prior findings highlight the relevance of fair distribution (e.g., Mazepus & van Leeuwen, 2019). However, it is important to note that these courses of action can also have negative implications, particularly when they exhibit rampant traits. Rampant flexibility or rampant inclusion refers to actions where the adverse manifestations of adaptation outweigh the positive effects on legitimacy compared to their associated alternatives. Considering the risk of rampant manifestations, prioritizing alternatives could result in fewer adverse effects on legitimacy after all.

3.1 Internal dilemma: Flexibility versus stability

During crisis management, governments and administrative organizations face an internal organizational dilemma between stability (following long-established laws, legal standards, and procedures) on the one hand and reacting more flexibly to new and unforeseen crises on the other hand (Comfort, 2007; Deverell, 2010; Lenz & Eckhard, 2023; Webb & Chevreau, 2006). Flexibility challenges the basic organizational logic of public administrations, which is based on accountability, legality, and transparency (Stark, 2014). Therefore, the question arises as to whether organizations adhere to their routines and remain relatively stable or whether they respond flexibly to the crisis.

On the one hand, the stability is targeted at transparency and traceability of bureaucratic processes. Governmental actors must be perceived as stable actors, who respond with integrity, and without bias to enhance their legitimacy (V. Schmidt & Wood, 2019). Hence, administrative structures and bureaucracy are designed to guarantee those norms through routines and rules. Stability and structure lower the possibility of abuse and misconduct, they provide transparency, accountability, and last but not least, they reduce uncertainty (Bogumil & Kuhlmann, 2015; Stark, 2014). Deviating from routine operating procedures compromises these aspects, causing a potential threat to how legitimate the crisis management process is publicly perceived.

On the other hand, rules can constrain outcomes within the organizational goals or public interest, particularly during crisis situations—which are characterized by uncertainties and a heightened sense of urgency. Instead, pragmatic solutions, flexibility, and creativity are necessary to uphold organizational performance, efficiency, or stakeholder protection (Ansell & Boin, 2019). Crisis management literature has so far emphasized the importance of flexibility as a facilitator of effective crisis governance, as it enables creative coping strategies and the decentralization of decision structures, among others (Deverell, 2010; Eckhard et al., 2021; Lenz & Eckhard, 2023). This positive effect of flexibility should not only matter from an organizational perspective but also a perspective of public legitimacy. As mentioned above, meeting public expectations is significant for legitimate governance. Flexible public administrations increase the ability to act and react to a crisis as well as the speed of the crisis response (Webb & Chevreau, 2006). This advantage in efficiency then directly relates to the citizen's expectations of their government to take control of the crisis (Christensen et al., 2019). Prior research findings suggest increases in citizens' trust levels if the administration was perceived as flexible and fast in crisis management (Lenz, 2022; Mizrahi et al., 2021a). Additionally, if the public observes how administrations react flexibly to crises instead of conforming to the negative stereotype of overly bureaucratic and indolent administrations, this adaptation can produce positive effects (e.g., Hvidman & Andersen, 2016; Willems, 2020).

Nevertheless, and despite the generally positive impact of flexibility, it is essential to consider its potential adverse effects, particularly at the expense of administrative accountability (Bovens & Schillemans, 2011; Stark, 2014). If flexibility adopts rampant characteristics, it can lead to the misuse of the newly gained leeway and the abuse of discretionary powers rules. In such scenarios, flexibility might still serve organizational goals aimed at enhancing adaptable and agile responses to crises, but it additionally may result in adverse outcomes such as favoritism, overspending, personal enrichment, and corruption. Consequently, while flexibility is initially expected to have a more positive effect on the legitimacy of crisis management compared to stable administrative action, rampant flexibility is expected to ultimately mitigate or even undermine legitimacy.

Hypothesis H1a.Compared to stability, flexibility in crisis management increases the perceived public legitimacy of the crisis management process.

Hypothesis H1b.When flexibility takes rampant traits, the legitimacy of the crisis management process decreases compared to stability.

3.2 External dilemma: Inclusion versus exclusion

The second dilemma crisis managers are confronted with is between exclusion and inclusion in the context of participatory processes (Harris et al., 2017; McLennan et al., 2021; Moynihan, 2009). This dilemma addresses organizational adaptations of public administrations at the external dimension, as it concerns the inclusion of civic engagement and participation in relief activities, which are omnipresent during disasters and crises. Hence, it pertains to the question of whether organizational boundaries become permeable, or if organizational boundaries remain rigid, thereby favoring exclusionary practices in the organization (Drabek & McEntire, 2003; Eckhard et al., 2021; Twigg & Mosel, 2017; Whittaker et al., 2015).

On the one hand, the inclusion of citizen volunteers plays an essential role in crisis management organizations. The mobilization and utilization of citizen volunteers in crisis management is a popular notion in research and among practitioners alike (Barsky et al., 2007; Kapucu, 2006; Whittaker et al., 2015). Effective cross-sector collaboration holds potential for public sector-citizen interaction in general and crisis management in particular (Kapucu, 2006; Martin & Nolte, 2020). Administrations that display good-quality networks usually perform better in crisis management (Eckhard et al., 2021), and inclusion is also a successful way to mobilize additional surge capacity (Whittaker et al., 2015). However, inclusion does not only matter from an organizational performance perspective; civil society involvement is also regarded as an expression of community resilience and a popular alternative to top-down solutions. Research on institutional trust and value literature emphasizes the positive effects of citizen participation on trust and legitimacy and addresses the openness and inclusiveness of the crisis governance process (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000; Moore, 1995). Providing opportunities for individuals and civil society organizations to become involved in the crisis governance process is thus expected to increase the throughput legitimacy of the crisis management process (Herian et al., 2012; Johansson et al., 2018; Vigoda-Gadot & Mizrahi, 2016).

One the other hand, while inclusion is a proven means of increasing public legitimacy and addressing the openness and inclusiveness of the crisis governance process, it is essential to acknowledge that participatory approaches come with adverse effects (Herian et al., 2012; Iusmen & Boswell, 2017). The involvement of a growing number of stakeholders can lead to inefficiencies and a reduction in accountability. Furthermore, a lack of understanding of interconnections and a holistic overview can further decrease effectiveness (Albris & Lauta, 2021; Bovens & Schillemans, 2011). These problems become even more pronounced in the context of crisis. Crisis situations are high-risk and high-insecurity environments involving a variety of actors with varying resources, skill levels, and access to information or communication channels, making cross-sector collaboration particularly challenging (Twigg & Mosel, 2017; Whittaker et al., 2015). First, in contrast to exclusion, inclusion can result in reduced efficiency and slower decision-making, potentially slowing down crisis responses (Iusmen & Boswell, 2017; Moynihan, 2009; Stark, 2014). Second, the inclusion of volunteers in the crisis response can lead to a dilution of responsibilities and accountability (Barsky et al., 2007; Drabek & McEntire, 2003; Harris et al., 2017; A. Schmidt, 2019). Additionally, multi-actor crisis management networks can pose challenges regarding liabilities. External actors often lack authority within the formal authorizing environment of the emergency management sector; they are often not bound by contractual or statutory obligation but rather act voluntarily. Meanwhile, any mistakes or wrong decisions can potentially jeopardize the safety and well-being of communities or first responders (Albris & Lauta, 2021; McLennan et al., 2021). Therefore, successfully integrating volunteers into crisis management can be challenging, and volunteers are often perceived as obstacles to efficient disaster response.

Consequently, despite the predominantly positive effects of inclusion and openness on the degree of public perceptions of legitimacy, adverse aspects of inclusion can potentially outweigh its benefits compared to their associated alternatives. Rampant inclusion can thus mitigate the positive effects of inclusivity due to a lack of accountability and organizational control resulting from increased coordination and networking expenses, an increased number of involved actors, and increased response complexity (Van Slyke & Roch, 2004). This is exemplified when liabilities evolve into minor scandals or authorities use external stakeholders as scapegoats to shift blame on case of any mishaps (Albris & Lauta, 2021).

Hypothesis H2a.Compared to exclusive behavior, including civil society actors in crisis management increases the perceived public legitimacy of the crisis management process.

Hypothesis H2b.When inclusion takes rampant traits, the legitimacy of the crisis management process decreases compared to exclusion.

3.3 Resource dilemma: Equality versus needs-based distribution

The third dilemma addresses the resource dilemma that public administrations encounter in crisis management. A crisis response involves the delivery of help to individuals but also administering help across societal groups (Henstra, 2010; Rivera & Knox, 2022; Sutter & Smith, 2017). Yet, crisis management is usually accompanied by a scarcity of resources and the question of adequate distribution. The resource dilemma pertains to the question of distributive justice, wherein administrations must decide between distributing resources based on equity or on the basis of needs (Anaya-Arenas et al., 2018). Hence, authorities must decide how the resources will be distributed, whether funds from some policy areas are to be reallocated and redirected to crisis relief, and which social groups will benefit. During a crisis, some groups might be more affected, more deprived of resources, and more in need of help than others. Administrations face a dilemma involving the choice between safeguarding the most vulnerable and providing assistance where it is urgently required, versus addressing the broader community-wide needs with a focus on ensuring equity (Gadson, 2020).

The resource dilemma differs from the two above in that it describes two competing alternatives but does not present a rampant category. Instead, the resource dilemma is characterized by a different pitfall for crisis managers: Authorities must weigh the effect of resource distribution on the efficiency of the crisis response and on fairness simultaneously (Gadson, 2020; Rivera & Knox, 2022). Needs-based distribution is characterized by its efficiency in swiftly reallocating resources to address the most urgent concerns. However, it may be perceived as less equitable, as only the most affected sub-group reaps the benefits. At the same time, including equity into the equation is difficult, as during crises a piori knowledge of what constitutes a fair distribution is often unknown since the exact consequences of the redistribution and the actual resource requirements cannot yet be estimated (Sutter & Smith, 2017). Hence, resource allocation considerations are highly unpredictable, making it challenging to identify the associated benefits and drawbacks.

In this context, prior research by Mazepus and van Leeuwen (2019) discovered that redistribution favoring the collective interest over individual interests enhances legitimacy in crisis situations. Additional studies on perceptions of fairness in resource allocation underscore the relevance of social psychological factors, such as interpersonal trust and group identity, in managing a shortage (van Vugt & Samuelson, 1999). In contested crises, where polarization around the topic, opposing arenas, and opinions are dominant in the public debate, it becomes almost impossible for the public administration to determine what a fair resource distribution is (Rosenthal et al., 2001). The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, showed that while all parts of the population were affected by the crisis, different groups have received help faster and less bureaucratically than others. During the 2015/16 migration crisis in Europe, discussions were even more polarized, as some social groups felt financially disadvantaged compared to the newly arriving refugees (Innes, 2010; Koch et al., 2020). Previous findings show that threat perceptions, institutional trust, and political ideology are important individual-level predictors for support in national help for refugees. At the same time, perceptions of the deservingness of refugees might interfere with fairness perceptions regarding resource allocations (Koos & Seibel, 2019).

Hypothesis H3.Compared to needs-based resource distribution, equity-based distribution increases the public legitimacy of the crisis management process.

4 DATA AND METHODS

4.1 Case selection: The 2015/16 migration crisis in Germany as guideline

The 2015/16 migration crisis in Europe is exemplary for such a transboundary crisis. It was boundary spanning and involved a pluralism of public sector services, requiring cooperation within and between organizations from the public and nongovernmental sectors. In Germany alone, the number of refugee-seeking people has grown exponentially between 2014 and 2016, reaching its peak in 2015 with over 1 million newly registered persons. From 2014 to 2016, the number of asylum seekers grew from 77.651 to 745.545 per year. In contrast, from 2011 to 2013, only around 260.000 new registrations were listed (BAMF, 2017). Especially the September 2015 decision to allow refugees marooned in Hungary to cross German borders lead to an abrupt increase in people that had to be cared for.

The situation was particularly challenging for administrations at the local level in Germany, where a large part of the crisis management competence is located. While the administrative system of asylum and migration policy in Germany is fragmented among all three federal levels, the local level districts—district-free cities and counties—are mainly in charge of all aspects regarding emergency response: they manage the accommodation, supply and support for the refugees as well as the complex administrative procedures lying behind that. Furthermore, they oversee medical and social support for asylum seekers. As such, they can be considered key actors in managing the German refugee crisis (Bogumil et al., 2016; Meyer, 2016). However, the local administration in most areas faced tremendous difficulties reacting to the massive influx of refugees; in many areas, the administration lost control of the situation. Apart from different degrees of affectedness and exposure to the influx of refugees, the local administration also differed in their capacity to react to the situation. While in some regions, crisis management structures could be applied relatively flexible, and civic engagement could be integrated into the administrative response, in other regions, the administration struggled to adapt quickly and was characterized by inertia and breakdown (Bogumil et al., 2016; Eckhard et al., 2021).

This local-level variation makes an excellent case to study legitimacy perceptions regarding crisis management decisions, as typical crisis management dilemmas manifested quite clearly during 2015/16 and therefore propose realistic scenarios for the experimental design. For example, there are several examples of semilegal action and decision-making during the refugee crisis 2015/16, such as housing and fire prevention regulation or tendering processes. While pragmatism and flexibility were necessary to respond to the urgency of the crisis, in some cases, adverse flexibility has provoked negative consequences, especially for public perception. In such situations, the trade-off might have been too big to justify a positive performance assessment. For example, the neglection of tendering procedures can thus lead to shorter processing periods on the one hand while resulting in excessive spending or favoritism on the other hand (IfD, 2016, Kirmaier & Zimmerly, 2015).

Similar observations have been reported for trade-offs regarding the inclusion of civil-society actors: On the one hand, the promotion, networking, and coordination of volunteers with full-time bureaucrats is costly and requires coordination committees, field offices, and staff bodies and waters down accountability (Hamann et al., 2016). On the other hand, voluntary engagement was important for local resilience and also the administrative ability to act in light of overburdening (Hamann et al., 2016). The question of fairness and resource distribution is also particularly interesting in the case of the 2015/16 migration crisis, as the individuals affected by the crisis were a vulnerable group that was not part of the host society. Distributional fairness is, therefore, relevant among refugees as well as between refugees and the host population. Although this distribution conflict is not new, it may have been exacerbated by the crisis. A survey in the United Kingdom, for example, showed as early as 2004 that 71% of voters perceived that refugees were prioritized regarding public service provision compared to citizens (Innes, 2010; Koch et al., 2020). At the same time, support and solidarity with refugees were very pronounced in the public discourses in Europe, and the majority of European citizens supported national help for refugees (Koos & Seibel, 2019).

4.2 Experimental design

To study the effects of crisis management dilemmas on public legitimacy of crisis management, a preregistered survey-based vignette experiment was employed2 (Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010; Auspurg & Hinz, 2014; Mutz, 2011). The vignettes systematically combined sets of explanatory characteristics and contextual information into scenarios. The data for the vignette experiment were gathered by the polling company YouGov, which recruited the survey respondents from a pre-existing online access panel with more than 200,000 registered panelists. A probability sample for the German population was drawn using adjusted quotas controlling for age (18–69 years), gender, education, and region of residence.3 As only the population over 18 years was considered, the sample slightly overrepresents older people (average age = 53) and pensioners (35%). The survey was fielded between November 4 and 17, 2020,4 as one module of a broader probability population survey. The sampling frame contained N = 3.009 individuals, of which 2.630 completed the vignette experiment, including 1283 men and 1140 women.5

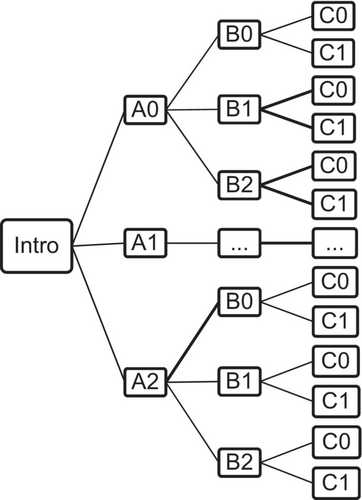

The vignette experiment was conducted in a 3 × 3 × 2 full-factorial between-subject design with 18 vignettes in total6 (Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the vignette treatments. In each vignette, participants were presented with a hypothetical but realistic scenario detailing local crisis governance that could have occurred during a migration crisis (the 2015/16 migration crisis in Germany described above served as orientation).7 Therefore, the comprehensibility of the questions and the validity of the answers were improved (Atzmüller & Steiner, 2010; Auspurg & Hinz, 2014). The short introduction and the crisis context, where their hypothetical district struggled severely with managing a significant increase in asylum seekers in a short period of time, remained constant over all vignettes. The manipulations then focused on the different governance decisions local districts chose to resolve the internal dilemma (A), the external dilemma (B), and the resource dilemma (C). The internal and external dilemma both had three levels: a control condition—0—where the vignette describes a situation without flexible/inclusive crisis management; a treatment condition—1—where the vignette describes a situation with flexible/inclusive crisis management; and a rampant treatment condition—2—where the vignette describes a situation that that explicitly showcases the adverse effects of adaptation, where both flexibility and inclusion led to accountability challenges. The third factor, resource dilemma, has two levels: a needs-based resource distribution (0), with reallocation of resources from a social to a refugee program; and an equity-based distribution (1) where no money was reallocated from other policy areas (cf. Table 1). Each respondent saw one vignette with a randomized combination of factor levels, with only one condition per factor (see Figure 1 and Table 2).8

| (0) | (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline condition | Treatment condition | Rampant treatment condition | |

| (A) Internal dilemma | Stability | Flexibility | Rampant flexibility |

| (B) External dilemma | Exclusion | Inclusion | Rampant inclusion |

| (C) Resource dilemma | Equity-based distribution | Needs-based distribution |

Please imagine that you and your family live in the fictional district of Hollerkreis. In the Hollerkreis district, there has been a significant increase in asylum seekers in a short period of time. As a result, the local administration is confronted with major challenges and sometimes even overwhelmed. Particular problems arise with the accommodation and care of the many asylum seekers. In the district, there are also many voluntary helpers: for example with acute emergency aid and care, support, and legal advice. The Hollerkreis administration adheres strictly to the applicable regulations during the exceptional situation. Existing standards will not be changed (e.g., specifications for awarding contracts to companies, building standards, etc.). These results in long processing times for new accommodations, but intransparencies in public construction contracts can be avoided (A0—Stability). The administration in the Hollerkreis district is reacting to the significant civil society commitment by forming joint working groups and a coordination office for civil society commitment. This means that responsibilities in the event of errors can no longer be clearly assigned afterward. However, volunteers are involved more often and can help shape more than in the neighboring district (B1—Inclusion). The financial resources in the Hollerkreis district are scarce. In some cases, existing budgets from the field of social and youth work are being reallocated to supply asylum seekers (C0—Efficiency-driven distribution). |

Having read this scenario, participants were asked to answer a series of questions about the process. To ensure the reliability of the study, the survey included validity and manipulation checks, as well as a limited amount of demographic information to check for successful randomization.

To measure the dependent variable perceived legitimacy, an aggregated index was constructed of serval questions that assessed the legitimacy of the local crisis response. The operationalization of legitimacy followed previous operationalizations of legitimacy as ordinal measure where legitimacy is understood as degree rather than a dichotomous phenomenon (Deephouse et al., 2017; Gau et al., 2012).9 Prior research served as a guide in creating the indicators for the index, in particular the measure of crisis management legitimacy introduced and tested by Mazepus and van Leeuwen (2019). Respondents indicated their agreement with several statements about the vignette on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from “Fully disagree” to “Fully agree.” All questions referred to different aspects of crisis management (e.g., the trustworthiness of government, trying to do what is best, and willingness to protest). The following statements were included: (1) “The local administration did it's best to control the situation”; (2) “I would completely trust the administration in this situation.”; (3) “For me, the administration's crisis management is justified and legitimate”; (4) “I would be ready to protest against the crisis management of this administration” (recoded). The items were transformed into the legitimacy index computed as the average response across these four items, with higher values indicating more perceived legitimacy. Reliability analysis indicated strong internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.85).

To control for random distribution of participants between vignettes, Chi2-tests of independence and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted. Randomization was successful as both, the Chi2-tests of independence and the ANOVA show no significant differences for any of the demographic variables between the vignettes.10 The manipulation checks yield similar results. Each of the manipulations shows the strongest correlation with its own manipulation check (Appendix III). However, flexibility and inclusion seem not to have resulted in entirely independent manipulations from the resource dilemma, which means that the adaptations in those crisis management practices seem not to be perceived as completely independent from each other. Finally, an additional question about respondents' satisfaction with the crisis management response was also included in the survey and is used to consolidate the results. The question can be used as a proxy for general performance perceptions of the local administration (Mizrahi et al., 2010) and is highly correlated with the legitimacy index (Pearson's correlation coefficient = 0.73, p < 0.00).11

5 RESULTS

Multifactor ANOVAs are conducted for data analysis and hypothesis testing. ANOVA allows for comparing more than two groups and is an appropriate technique for analyzing factorial design data. To estimate the effect size, the partial eta-squared statistic (η2) is calculated. A Tukey post hoc test was conducted to identify the size of the differences between the single factors.

5.1 Hypothesis testing

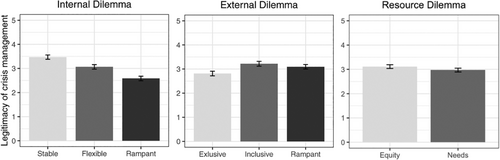

Does the choice of governance alternatives alter the degree of perceived legitimacy of the crisis management process by the public? In order to analyze the main effects of each manipulated factor, various ANOVAs are performed. Table 3 shows the full ANOVA, containing all manipulated factors, interactions, and control variables.12 The results show that the main effects for the three manipulated factors are all significant (p < 0.05 for the resources dilemma and p < 0.001 for internal/external dilemma), indicating that all three manipulated factors matter for the levels of perceived legitimacy of crisis management. Of the three factors, the biggest effect sizes are observed for the internal dilemma with a partial η2 of 0.075, followed by the external dilemma (partial η2 = 0.022), and finally, the resource dilemma with the smallest effect (partial η2 = 0.003).

| Legitimacy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | df | F | p | Effect size partial η2 |

| Internal dilemma | 2 | 85.776 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

| External dilemma | 2 | 24.103 | 0.000 | 0.022 |

| Resource dilemma | 1 | 6.246 | 0.013 | 0.003 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Internal × external | 4 | 2.054 | 0.084 | 0.004 |

| Internal × resource | 2 | 4.238 | 0.015 | 0.004 |

| External × resource | 2 | 0.564 | 0.569 | 0.001 |

| Internal × external × resource | 4 | 0.736 | 0.567 | 0.001 |

| Additional analysis | ||||

| Gender | 1 | 0.466 | 0.495 | 0.000 |

| Age | 1 | 2.365 | 0.124 | 0.001 |

| Political interest | 1 | 6.416 | 0.011 | 0.003 |

| Party | 7 | 24.202 | 0.000 | 0.075 |

| Number of Obs. | 2129 | |||

| Residuals df | 2101 | |||

| R-squared | 0.168 | |||

To further investigate differences between the levels of manipulations, mean differences are depicted graphically (Figure 2) and calculated using the Tukey post hoc test (Table 4). Regarding the internal dilemma between flexibility and stability, the results do not support H1a that flexibility, compared to stability, increases the perceived legitimacy of the crisis management process. Instead, the results show the highest mean of legitimacy for stable behavior in crisis management (3.47). The Tukey post hoc test reveal that a flexible crisis response of the local administration, as opposed to rule-based behavior, results in lower averages of legitimacy (−0.404, p < 0.001). Hypothesis H1a must therefore be rejected. Hypothesis H1b was concerned with the negative consequences of rampant flexibility, where adverse effects of flexibility cause abuses of leeway and mitigate the positive effects compared to stability. The results confirm the mitigating effects of rampant flexibility on legitimacy, confirming H1b. The abuse of flexibility results in an average mean of 2.59 in legitimacy with a difference of −0.884 points of legitimacy compared to stable behavior in crisis management (p < 0.001) and −0.480 for legitimacy compared to flexible behavior in crisis management (p < 0.001).

| Legitimacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal dilemma | External dilemma | Resource dilemma | |||

| Flexible—Stable | −0.404*** | Inclusive—Exclusive | 0.403*** | Equity-based—Needs-based distribution | 0.141** |

| Rampant—Stable | −0.884*** | Rampant—Exclusive | 0.278*** | ||

| Rampant—Flexible | −0.480*** | Rampant—Inclusive | −0.125 | ||

- Note: The preferential practices are highlighted in bold. Results are based on ANOVA with interaction but without controls, N = 2.630.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

Regarding the external dilemma between inclusiveness and exclusiveness, the results support H2a that inclusion, compared to exclusion, increases the perceived legitimacy of the crisis management process. The mean of legitimacy for inclusive governance is 3.23; in contrast, exclusive behavior compared to inclusive crisis management shows significantly lower results on legitimacy (−0.403, p < 0.001). H2a can thus be confirmed. Hypothesis H2b addresses the adverse effects of inclusion, where inclusion leads to liabilities and decreased accountability, mitigating the positive effects of inclusion compared to exclusion. The results do not confirm the hypothesis, as there is no statistically significant difference between rampant behavior and inclusive behavior (−0.125, p < 0.145). Rampant inclusiveness is hence perceived as more legitimate than exclusion from the crisis management process (0.278, p < 0.001). H2b must be rejected, as even when inclusion exhibits rampant traits, crisis management is perceived as more legitimate than for the exclusion treatment and equally legitimate as for the standard inclusion treatment.

Hypothesis H3 suggested that, in comparison to needs-based resource distribution, equity-based distribution enhances the public legitimacy of the crisis management process. The findings support the hypothesis, although the observed effects are relatively small. The mean legitimacy score for equity-based distribution is only 0.141 points higher than that of needs-based distribution (p < 0.01, with a mean needs-based score of 2.97). This underscores that needs-based resource distribution is associated with a reduction in the perceived legitimacy of crisis management when contrasted with equity-based resource distribution, thus confirming H3.

5.2 Additional analysis

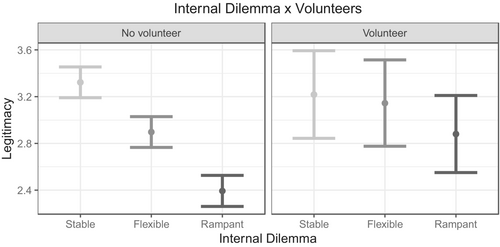

Randomization in experimental designs serves to balance observable and unobservable factors that might influence outcomes, effectively controlling for differences between individuals. Nevertheless, it can be useful to examine some additional variables to gain further insights into the differences in attitudes toward legitimacy.13 To this end, additional individual-level variables were included to account for heterogeneous treatment effects. One specific effect merits emphasis: the heterogeneous treatment effect observed among volunteers as compared to the general population (the volunteer variable asked whether respondents were actively engaged as volunteers during the migration crisis 2015/16).14 Volunteers are a particularly interesting subgroup of the population, given their direct involvement in the crisis management response and close interaction with local administrations. Furthermore, previous research suggested positive effects of flexibility on legitimacy, which must be rejected in this study so far.

Interestingly, in contrast to the findings concerning the general population, the additional analysis reveals distinct effects on volunteers' perceptions of legitimacy (Figure 3 and Appendix IV). The results not only demonstrate that, overall, volunteers tend to perceive crisis management responses as more legitimate when compared to the general population (0.249, p > 0.05), but they also confirm heterogeneous treatment effects regarding the internal dilemma (Figure 3). Volunteers perceive stability and flexibility as equally legitimate, as long as flexibility does not take rampant behavior. In other words, when comparing volunteers to the general population, the effect of flexibility on legitimacy appears to change. The findings for volunteers show no significant differences in the degree of legitimacy between stable and flexible crisis management; however, rampant flexibility still has the most damaging effects. Ultimately, these results are in line with the findings of Lenz (2022) and underscore the specific dynamics for volunteers during crises.

6 DISCUSSION

The analysis reveals three initial insights into public perceptions of crisis management dilemmas. First, for bureaucracies whose central characteristics revolve around predictability and procedural legitimacy (Deephouse et al., 2017; Stark, 2014), the necessary short-term adjustments prompted by crises can lead to a decline of legitimacy. The findings indicate decreased levels of legitimacy for flexible crisis management compared to stable crisis management. Flexibility and the capability of administrations to move away from traditional routines are not positively associated with legitimacy. Despite the negative reputation of bureaucracies as slow and inert (Hvidman & Andersen, 2016; Willems, 2020), citizens prioritize stability over flexibility in the crisis management process, and more so if the adverse effects of flexibility are apparent. In light of the existing literature on crisis management effectiveness and the imperative of flexibility and adaptability in crisis management (Ansell & Boin, 2019; Eckhard et al., 2021; Moon, 2020), this finding introduces an additional layer of complexity to crisis management practice.

At the same time, the additional analysis reveals heterogeneous effects with regards to the dilemma between flexibility and stability. Specifically, volunteers as a subgroup within the population tend to evaluate flexibility more positively than the general population; there is no significant reduction in legitimacy levels compared to stability within the volunteer group. This observation is in line with previous findings on the effects of crisis volunteering on trust in government (Lenz, 2022; A. Schmidt, 2019). However, these nuanced results suggest that this study can only provide an initial contribution toward a better understanding of the complex dynamics at play. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between crisis-induced administrative adaptations and their subsequent impact on legitimacy. This investigation should include different subgroups of the population and their expectations. For instance, potential explanations for the differences in perceptions may be rooted in the level of interaction and understanding of local administrative practices. Additionally, the perceived urgency of crisis management could play a role, driven by risk perception or intrinsic and humanistic motivation (Karakayali, 2019; Ma & Christensen, 2019). Regarding implications for crisis management practice, these preliminary findings suggest a need to focus on mitigating the adverse effects of flexibility, given that stability is often an impractical option when responding to urgency. Additionally, they should invest in crisis communication to enhance the comprehensibility of their actions.

Second, and in line with previous findings on citizen participation and volunteer inclusion (Herian et al., 2012; Johansson et al., 2018), including civil society actors in the crisis management response has pronounced and positive effects on process legitimacy, as opposed to excluding external actors. This observation holds even when the adverse effects of inclusion are directly showcased. The additional analysis also reveals another positive effect of volunteer involvement, namely that they generally exhibit higher degrees of legitimacy. The findings underscore the relevance of inclusive crisis management and imply that crisis managers should always put particular emphasis on including civil society actors, even if the inclusion is costly or time-consuming.

Third, the results show that equity-based resource allocation, as opposed to needs-based resource reallocation, is perceived as more legitimate. However, the effect sizes for the differences between these alternatives are relatively small. On the one hand, considering the discussion about what is perceived as fair in the first place and the dependence of these perceptions on psychological factors, as well as individuals' needs and group membership, the relatively small effect may not be all too surprising (van Vugt & Samuelson, 1999). On the other hand, this limited effect could be attributed to the specific scenario of the migration crisis, as this situation involved reallocating resources toward an outgroup in a polarized setting, where some parts of the host population perceived them as less deserving or felt disadvantaged by their government's actions (Koch et al., 2020). Crisis managers should thus be aware of equity considerations even as they pursue the most efficient crisis response strategies.

This already points toward the first limitation of the study, namely generalizability of the results. The study design features only one crisis in one country, namely a hypothetical migration crisis in the German context. Migratory crises are very particular crises, as they are not only transboundary and polarized in nature, but also feature a group distinction between the primarily affected population (refugees) as an outgroup and the host population as ingroup (Ansell et al., 2010; Koch et al., 2020). The nature of the crisis most certainly affects legitimacy perceptions, particularly with regards to distributional justice, but potentially also with regards to the internal and external dilemma. For instance, it is reasonable to expect that adverse effects might be more tolerable when individuals feel a stronger sense of identification with the affected population. Furthermore, the study was conducted among a German population sample, and there is a possibility of varying effects among citizens in different countries that cannot be controlled for. Therefore, the findings of this study can only be preliminary insights toward a better understanding of the interplay between crisis management alternatives and perceived throughput legitimacy. Testing the effects of crisis management governance on throughput legitimacy for various crises and across different countries would be an important avenue for future research.

Additionally, the findings are limited to the treatment conditions in experiments. In this article, flexibility, inclusion, and fairness were operationalized as dilemmas with specific characteristics. The results could change given other operationalizations. Replicating the experiment with an adapted operationalization of the treatments could also be a fruitful option for future research. Finally, experimental research allows for the inclusion of a limited number of variables, and randomization only accounts for specific confounding factors. However, due to the specific vignette survey design, some validity due to the cross-sector features was achieved, and several additional variables could be included (Mutz, 2011). Considering the relatively small size of variance in legitimacy that is explained by the organizational crisis governance in the analysis, other factors on the individual level as well as at the level of crisis management outcomes that could not be included in this study should be further investigated.

7 CONCLUSION

This research aims to investigate how the crisis management process relates to public legitimacy. It combines literature on organization theory, crisis management research and legitimacy literature and centers around three central organizational and crisis management dilemmas—flexibility versus stability in internal reactions, inclusion versus exclusion of external actors, and equity versus needs-based resource distribution—which are then theoretically linked to their effects on public legitimacy. By focusing on these three managerial dilemmas, the paper emphasizes process legitimacy, directly asking how management decisions or behavior affect how the public perceives crisis management. Empirically, the paper draws on a vignette experiment with survey data from 2.630 German respondents. The experimental design allows presenting the respondents with hypothetical crisis scenarios that were managed in different ways. While these hypothetical settings are constructed and come with limitations, the method nevertheless enables studying public perceptions during crises. Because of the highly vulnerable context of crisis, surveying those affected in actual disasters is technically and ethically difficult.

The findings contribute to the current state of crisis management literature by corroborating the relevance of the governance process for crisis management evaluations and perceived public legitimacy (Mazepus & van Leeuwen, 2019; Rivera & Knox, 2022). The findings highlight the relevance of transparency and legality, inclusion, and fairness of crisis management, while at the same time conceptualizing adverse effects of specific managerial options on process legitimacy. As such, the findings directly speak to the bigger conundrum between internal governance effectiveness and external governance legitimacy in crisis management (Boin & Rhinard, 2022; Christensen et al., 2016; Mizrahi et al., 2021a) and add a public perspective on the primarily technical and organizational field of studies. More broadly speaking, the findings resonate with others who discuss the legitimacy of bureaucratic discretion and associated legitimacy dilemmas between effectiveness through rule stretching (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000; Keiser, 1999; Rivera & Knox, 2023) versus violations of norms and subjectivity to individual judgments (Bell et al., 2021).

The findings of this research also have tentative practical implications for the way how administrations should think about the legitimacy of their crisis response. Administrations are dependent on public legitimacy, as it affects government capacity. Higher levels of legitimacy and trust in public organizations increase citizen compliance with laws and regulations, thus enhancing the effectiveness of the crisis response (Beetham, 1991; Easton, 1967; Marien & Hooghe, 2011; Schraff, 2020). Some governance practices, however, while increasing internal effectiveness, are associated with decreased levels of perceived throughput legitimacy. Furthermore, legitimacy perceptions depend on citizen expectations; public administrations need to consider expectations and motivations but also understand that their governance decisions will potentially satisfy some but not others. In conclusion, as a profession, public administration needs a better understanding of the public's perception of fairness and legitimacy in crisis management and how it can be pursued through certain governance alternatives more than others.

Finally, this study offers preliminary results of how legitimate citizens perceive the actions of governments during crisis management. Considering the comparable relevance of both process and outcome legitimacy (Van Ryzin, 2011; Vigoda-Gadot & Mizrahi, 2016), this study serves as addition to the existing research, which has so far predominantly focused on the perceptions of outcomes. However, the boundaries of this article also extend an invitation to explore a broader research agenda that addresses the relationship between process and outcomes for crisis management legitimacy. There is still a lack of knowledge about the extent to which process and outcome legitimacy interact with each other, for example, to what extent they mutually reinforce or contradict each other. Moreover, the legitimacy of crisis management process could serve to legitimize particular outcomes or even translate, to some extent, into broader diffuse legitimacy for public administration (Flink & Xu, 2024; Ma & Christensen, 2019; Stark, 2010). A more extensive exploration of the multidimensional relationship between process and outcomes is thus necessary, and could further explore areas such as the discrepancy between actual performance and citizen perceptions (Stipak, 1979) or the role of outcome favorability (Mazepus & van Leeuwen, 2019).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank Steffen Eckhard, Sebastian Koos, Maximilian Haag, and Franziska Graf for their feedback and comments on the paper. The author is also thankful for the constructive feedback received during presentations at IRSPM and ECPR, as well as the helpful suggestions from the anonymous reviewers. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. WOA Institution: ZEPPELIN UNIVERSITAET GGMBH. Consortia Name: Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The data collection for this article has been conducted in the context of the HybOrg research project (https://www.hyborg-projekt.de/en/), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 01UG1826BX).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author has no conflict of interest to declare

Endnotes

Open Research

OPEN RESEARCH BADGES

This article has earned a Preregistered Research Designs badge for having a preregistered research design, available at https://osf.io/3uv6h.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Supplemental material for this article is available online. The preregistration is available at https://osf.io/3uv6h.