Effects of treatment cessation and re-treatment in randomized controlled trials of prucalopride in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation

Abstract

Background

Prucalopride is a selective, high-affinity serotonin type 4 receptor agonist approved for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) in adults. We investigated the impact of prucalopride cessation and re-treatment on efficacy and safety.

Methods

Data were from two randomized controlled trials in adults with CIC. In a dose-finding trial, complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBMs) and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were assessed during a 4-week run-out period after a 4-week treatment period (TP; prucalopride 0.5–4 mg once daily or placebo). In a re-treatment trial, CSBMs and TEAEs were assessed during two 4-week TPs (prucalopride 4 mg once daily or placebo) separated by a 2- or 4-week washout period.

Key Results

In the dose-finding trial (N = 234; 43–48 patients/group), mean CSBMs/week and the proportion of responders (≥3 CSBMs/week) were higher with prucalopride than placebo during the TP, but similar in all groups 1–4 weeks after treatment cessation. TEAEs were less frequent following treatment cessation. In the re-treatment trial (efficacy analyses: prucalopride, n = 189; placebo, n = 205), the proportion of responders was similar in both TPs and significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001) with prucalopride (TP1, 38.6%; TP2, 36.0%) than placebo (TP1, 10.7%; TP2, 11.2%). Most patients who responded to prucalopride in TP1 responded again in TP2 (71.2%). TEAEs were less frequent in TP2 than TP1.

Conclusions and Inferences

Prucalopride cessation resulted in a loss of clinical effect to baseline levels within 7 days. Similar efficacy and safety were observed between TP1 and TP2 after prucalopride was re-initiated following a washout period.

Key Points

- Patients with chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) may experience intermittent episodes of worsening symptoms and may therefore start and stop their medication.

- The impact of discontinuation and re-introduction of CIC therapy on safety and efficacy has not been previously evaluated.

- Analyses of data from two randomized controlled trials in adults with CIC demonstrated that the clinical effect of prucalopride is diminished within 1 week of treatment cessation; however, following re-initiation of treatment after 2 or 4 weeks, the efficacy and safety of prucalopride were maintained.

- These findings provide key insights for the management of patients with CIC relatable to a real-world clinical setting.

1 INTRODUCTION

Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) is a common functional bowel disorder characterized by a range of symptoms including abdominal pain and bloating, straining, lumpy or hard stools, infrequent defecation, and sensation of incomplete evacuation.1, 2 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, the global prevalence of CIC in adults was 14%, with higher rates in women and older individuals.2 Symptoms frequently present as severe in nature and patients with CIC often have impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and reduced work productivity, with symptom severity negatively correlated with perceived well-being.3-7 Poor HRQoL in patients with CIC has been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of increased healthcare resource utilization.8 Based on a prevalence of 14%, it is estimated that approximately 46 million adults in the United States have CIC, which imposes a substantial economic and healthcare burden.2, 5, 7, 9

CIC management often includes lifestyle and diet modifications, followed by over-the-counter treatment options, and then escalation to prescription medications in a limited percentage of patients.6, 10 Dissatisfaction with CIC treatment is common.6 In a USA-based online survey published in 2017, 59% of adults with CIC receiving prescription therapy were dissatisfied with their treatment, and 78% of healthcare professionals felt that there was room for improvement with the prescription therapies available at the time.6

Prucalopride is a selective, high-affinity serotonin type 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist approved in the United States for the treatment of CIC in adults.11-13 As a gastrointestinal prokinetic agent, prucalopride stimulates high-amplitude propagating contractions in the colon, increasing bowel motility.13, 14 In an integrated analysis of six double-blind, randomized controlled trials in adults with CIC (five phase 3 trials and one phase 4 trial; N = 2484), 1 mg and 2 mg once-daily doses of prucalopride improved the frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBMs) per week versus placebo over a 12-week period.15 Prucalopride also improved CIC-associated symptoms and was well tolerated, with no safety signals of concern.15

Prucalopride has been used in several countries for over a decade, including in the European Union where it was approved in 2009.16 However, approval in the United States was in 2018 for use in adults with CIC at a dosage of 2 mg once daily, or 1 mg once daily in patients with concomitant CIC and severe renal impairment.13 Therefore, clinical experience of prucalopride use in the United States is limited compared with other countries.

Patients with CIC may experience intermittent episodes of symptoms9, 17 and may therefore stop and re-start their medication according to current symptom severity. The impact of this discontinuation of therapy on prucalopride efficacy and safety parameters has not been evaluated and remains unknown in the clinical management of CIC. Our aim was to investigate the effects of prucalopride cessation on the durability of response and clinical safety and, separately, whether re-treatment with prucalopride would provide a similar response as observed with the initial course of therapy. This post hoc analysis used data from two separate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in adults with CIC.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study overview and patient population

Data were analyzed from two non-sequential, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in adults (≥18 years old) with a diagnosis of CIC. The first was a phase 2 dose-finding trial conducted between September 1996 and June 1997 (PRU-USA-3; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00596596) across 26 sites all in the United States.18 The second was a phase 3 re-treatment trial conducted between April 1999 and February 2000 (PRU-USA-28; NCT00598338) across 33 sites all in the United States.19, 20 In these trials, patients and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation. Both trials were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. The study protocols and amendments were reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees/institutional review boards. All patients provided written informed consent before their participation.

In both trials, CIC was defined as experiencing two or fewer CSBMs per week for 3–6 months in addition to one or more of the following for at least 25% of the duration of that period: hard or lumpy stools, a sensation of incomplete evacuation or straining during defecation. This definition is similar to the current Rome IV criteria for functional constipation,1 and in line with the definition of chronic constipation in other prucalopride clinical studies.15 Patients with drug-induced constipation or secondary constipation due to causes such as endocrine, metabolic, or neurologic disorders; organic disorders of the large bowel; or surgery were excluded from participation. At the start of both trials, patients were instructed not to change their diet or lifestyle, or use laxatives or other agents (e.g., anticholinergics) during the studies. In addition, use of an investigational drug 30 days before the run-in phase was an exclusion criterion for both studies. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in the Supplementary Information. Participants who did not experience a bowel movement for 3 or more consecutive days throughout the studies (including during the run-out/washout periods) were permitted to receive bisacodyl as rescue medication. A maximum single dose of 15 mg (three 5 mg tablets) of bisacodyl was prescribed, with an increase in dose allowed only after the patient had contacted the investigator. In the phase 2 dose-finding and phase 3 re-treatment trials, patients were randomly allocated to one of five treatment arms (block size of five) or one of two treatment arms, respectively. For both trials, randomization was based on a computer-generated randomization code provided by Janssen Research Foundation. Patient numbers were assigned in a consecutive order starting with the lowest number available.

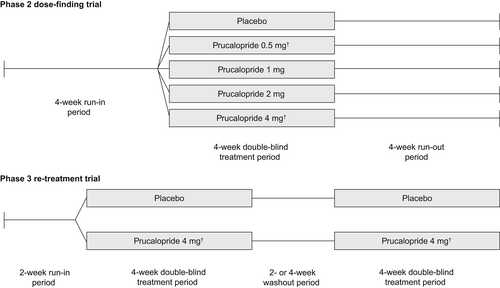

2.2 Phase 2 dose-finding trial

Participants in the phase 2 dose-finding trial (PRU-USA-3; NCT00596596) first completed a 4-week run-in period to confirm the existence of chronic constipation and eligibility for the study. This was followed by a 4-week double-blind dose-finding period, during which patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1:1) to receive either placebo or prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mg once daily before breakfast, and a subsequent 4-week run-out period (Figure 1). The prespecified primary endpoint was the proportion of responders (defined as patients with at least three CSBMs per week) at the end of double-blind treatment. A sample size of at least 31 patients in each treatment group was selected to detect a significant difference in response between placebo and the optimal dose of prucalopride at the two-sided 5% significance level, with a power of 80% (assuming a response in 30% of patients receiving placebo and 65% of patients receiving prucalopride). To evaluate the effects of treatment cessation in the analysis presented here, the proportion of responders, the mean number of CSBMs per week and the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were assessed during the 4-week run-out period.

2.3 Phase 3 re-treatment trial

The phase 3 re-treatment trial (PRU-USA-28; NCT00598338) consisted of a 2-week run-in period to confirm the existence of chronic constipation followed by two 4-week double-blind treatment periods, during which patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either prucalopride 4 mg or placebo once daily before breakfast. The two treatment periods were separated by a washout period of 2 weeks or 4 weeks, depending on the time required for each patient to meet the criteria for CIC again (Figure 1). Patients who failed to requalify after 4 weeks were discontinued from the study. The prespecified primary endpoint was the proportion of responders (defined as patients with at least three CSBMs per week) during each of the two treatment periods. Sample size calculations were based on data from phase 2 studies (NCT00617513, NCT00631813, NCT00596596). A total of 159 patients in each group with data in the second treatment period was required to detect a difference from placebo of 15% at the two-sided 5% significance level, with a power of 90%. A sample size of 250 randomized patients per treatment group was therefore selected (assuming a discontinuation rate prior to the start of the second treatment period of 15% and that 75% of patients would requalify as having CIC again at the end of the washout period). To evaluate the effects of re-treatment in the current analysis, the proportion of responders and the incidence of TEAEs were assessed during both treatment periods.

2.4 Outcome measures

In both trials, patients were required to record the date and time of CSBMs in a daily diary. During the phase 2 dose-finding trial, primary and secondary efficacy analyses were performed using the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all randomized patients who had received at least one dose of study drug and had data available from at least one post-baseline primary efficacy assessment (i.e., at least 4 days of diary data in a week). In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, the primary efficacy endpoint was assessed using the efficacy analyzable (EA) population, defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug in each of the two treatment periods and had at least 7 days of non-missing diary data after week 1 in each of the two treatment periods. The EA population was the primary population for analyses of efficacy data in this phase 3 re-treatment trial; however, these efficacy analyses were also performed separately in the ITT population (defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least 7 days of non-missing diary data after the first week in one of the two treatment periods). Safety outcomes were assessed in both trials using the safety analysis sets, which were defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug in either trial. In the phase 2 dose-finding trial, parameters with missing diary data for more than 3 days of an analysis period were recorded as missing for that period and were excluded. If diary data were available for at least 4 days in a 7-day period these were adjusted to a weekly score. In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, patients who had fewer than 7 days of diary data after week 1 in the first or second treatment period were excluded from efficacy analyses. For patients who had at least 7 days of diary data after week 1 but did not complete the diary up to day 28, the last 7 days recorded were used to impute the missing information up to the end of the treatment period (last observation carried forward). TEAEs were summarized according to World Health Organization preferred terms.

2.5 Data analyses

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were summarized descriptively (n, % or mean, standard error [SE]), as were the proportion of responders and the incidence of TEAEs (n, %). In the phase 2 dose-finding trial, the proportions of overall responders in the prucalopride and placebo groups were compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, and the mean (SE) number of CSBMs per week was reported descriptively. In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, the proportions of responders in the prucalopride and placebo groups during each treatment period were compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient demographics and disease characteristics

In the phase 2 dose-finding trial, a total of 234 patients with CIC were randomized to receive prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 mg once daily or placebo (Figure S1A). Three patients who were randomized to receive double-blind treatment did not take trial medication and were excluded from the analyses. The baseline demographics and disease characteristics for the 231 patients who entered the double-blind treatment phase are presented in Table 1.

| Dose-finding trial with 4-week run-out period (phase 2)a | Re-treatment trial (phase 3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic/characteristic | Placebo (n = 46) | Prucalopride | Placebo (n = 257) | Prucalopride | |||

| 0.5 mgb (n = 43) | 1 mg (n = 48) | 2 mg (n = 48) | 4 mgb (n = 46) | 4 mgb (n = 253) | |||

| Age, years, mean (SE) | 43.0 (1.5) | 42.7 (1.6) | 39.6 (1.4) | 41.2 (1.7) | 44.2 (1.8) | 46.3 (0.9) | 45.9 (0.9) |

| Age, years, range | 25–70 | 22–67 | 23–66 | 23–70 | 21–70 | 18–78 | 18–89 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Women | 44 (95.7%) | 36 (83.7%) | 44 (91.7%) | 45 (93.8%) | 43 (93.5%) | 226 (87.9%) | 230 (90.9%) |

| Men | 2 (4.3%) | 7 (16.3%) | 4 (8.3%) | 3 (6.3%) | 3 (6.5%) | 31 (12.1%) | 23 (9.1%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 40 (87.0%) | 39 (90.7%) | 41 (85.4%) | 44 (91.7%) | 38 (82.6%) | 206 (80.2%) | 206 (81.4%) |

| Black | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (4.7%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2 (4.2%) | 6 (13.0%) | 38 (14.8%) | 29 (11.5%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (4.7%) | 3 (6.3%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | 11 (4.3%) | 13 (5.1%) |

| Asian | 1 (2.2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Other | 1 (2.2%) | 0 | 2 (4.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0 | 5 (2.0%) |

| Duration of constipation, years, mean (SE) | 21.4 (2.1) | 24.9 (2.5) | 18.2 (1.9) | 19.8 (2.1) | 22.5 (2.5) | 23.6 (1.1) | 21.8 (1.1) |

| Duration of constipation, years, range | 2–54 | 1–61 | 1–47 | 1–50 | 1–64 | 1–70 | 1–89 |

| Frequency of CSBMs per week, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 90 (35.0%) | 73 (28.9%) |

| >0 to ≤1 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 93 (36.2%) | 108 (42.7%) |

| >1 to ≤3 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 70 (27.2%) | 67 (26.5%) |

| >3 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 4 (1.6%) | 5 (2.0%) |

| CSBMs per week, mean (SE) | 1.1 (0.08) | 0.9 (0.11) | 1.0 (0.08) | 0.9 (0.11) | 0.9 (0.08) | NC | NC |

| Main complaint, n (%) | |||||||

| Infrequent defecation | 18 (39.1%) | 22 (52.4%)c | 16 (33.3%) | 18 (37.5%) | 17 (37.0%) | 90 (35.0%) | 85 (33.6%) |

| Difficulty defecating/straining | 13 (28.3%) | 9 (21.4%)c | 14 (29.2%) | 13 (27.1%) | 16 (34.8%) | 37 (14.4%) | 39 (15.4%) |

| Abdominal bloating | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | 68 (26.5%) | 58 (22.9%) |

| Abdominal distention | 7 (15.2%) | 7 (16.7%)c | 5 (10.4%) | 7 (14.6%) | 8 (17.4%) | NC | NC |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation | 6 (13.0%) | 0c | 7 (14.6%) | 6 (12.5%) | 3 (6.5%) | 25 (9.7%) | 42 (16.6%) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.4%)c | 4 (8.3%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0 | 21 (8.2%) | 19 (7.5%) |

| Hard stools | 1 (2.2%) | 3 (7.1%)c | 1 (2.1%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 16 (6.2%) | 10 (4.0%) |

| Other | 0 | 0c | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1 (2.2%) | NC | NC |

| Treated with diet, n (%) | 24 (52.2%) | 26 (60.5%) | 25 (52.1%) | 26 (54.2%) | 26 (56.5%) | 166 (64.6%) | 186 (73.5%) |

| Treated with bulk-forming agents, n (%) | 18 (39.1%) | 13 (30.2%) | 21 (43.8%) | 8 (16.7%) | 19 (41.3%) | 152 (59.1%) | 160 (63.2%) |

| Treated with laxatives, n (%) | 40 (87.0%) | 31 (72.1%) | 40 (83.3%) | 39 (81.3%) | 39 (84.8%) | 217 (84.4%) | 222 (87.7%) |

| Therapeutic effect, n (%) | |||||||

| Adequate | 12 (26.1%) | 9 (20.9%) | 13 (28.3%)d | 9 (18.8%) | 8 (17.4%) | 73 (29.8%) | 69 (27.9%) |

| Inadequate | 34 (73.9%) | 34 (79.1%) | 33 (71.7%)d | 39 (81.3%) | 38 (82.6%) | 172 (70.2%) | 178 (72.1%) |

- Abbreviations: CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; NC, not calculated; SE, standard error.

- a Of 234 patients who were randomized to receive double-blind treatment, three did not take trial medication.

- b Not an approved dose of prucalopride.

- c Data available for 42 patients.

- d Data available for 46 patients.

In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, a total of 516 patients with CIC were randomized to receive prucalopride 4 mg once daily or placebo (Figure S1B). Of 510 patients who entered treatment period 1, 394 were included in the EA population (prucalopride 4 mg, n = 189; placebo, n = 205). All 510 patients were included in the safety analysis. The baseline demographics and disease characteristics for the 510 patients who entered treatment period 1 are presented in Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups in both studies (Table 1). In the phase 2 dose-finding trial, 91.8% of participants were women and the mean age was 42 years. Of these patients, 189 (81.8%) required laxatives in the past 6 months and 178 (77.7%) considered their previous therapy inadequate. In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, 89.4% of participants were women and the mean age was 46 years. Most of these patients (n = 439, 86.1%) utilized laxatives and 350 (71.1%) considered their previous therapy inadequate.

3.2 Effect of prucalopride treatment cessation on efficacy parameters

In the phase 2 dose-finding trial, the proportion of patients achieving response throughout the entirety of the 4-week, double-blind treatment period (defined as those with at least three CSBMs per week) was higher with prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg (24.4%, 23.4%, 32.6%, and 55.6%, respectively) than with placebo (13.3%). This difference versus placebo was significant for the prucalopride 2 mg (p ≤ 0.05) and 4 mg (p ≤ 0.01) doses. During the 4-week run-out period, of patients who had received prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg, the proportion of responders over the 4 weeks decreased to 7.5%, 11.6%, 12.5%, and 10.0%, respectively, compared to 16.7% in the placebo group. The differences versus placebo were not statistically significant for any of the prucalopride groups.

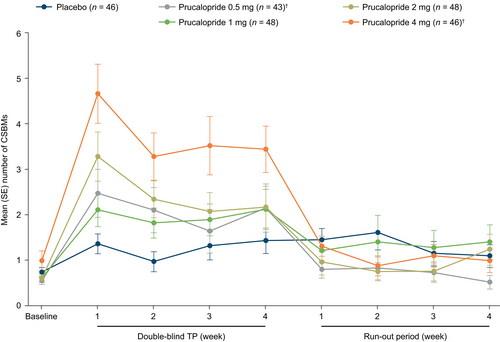

The mean number of CSBMs per week was higher in the prucalopride groups (prucalopride 0.5 mg, 2.06; prucalopride 1 mg, 1.95; prucalopride 2 mg, 2.43; and prucalopride 4 mg, 3.96) than in the placebo group (1.28) during the 4-week treatment period (Figure 2). In contrast, during the 4-week run-out period, the mean number of CSBMs per week was similar (approximately 1 CSBM/week) in the prucalopride and placebo groups. A reduction in the mean number of CSBMs to a frequency equivalent to the placebo group was observed as early as 7 days after the last dose of prucalopride (Figure 2).

During the treatment period, use of rescue medication (bisacodyl) was reported in 49%, 46%, 68%, and 33% of patients receiving prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg, respectively, and in 67% of patients receiving placebo. In the run-out period, bisacodyl usage was similar across the treatment groups (64%–70%).

3.3 Effect of prucalopride treatment cessation on safety parameters

TEAEs were predominantly gastrointestinal in nature and were reported less frequently during the run-out period than during the double-blind treatment period of the phase 2 dose-finding trial (Table 2). During the treatment period, TEAEs were reported by 27 (62.8%), 40 (83.3%), 37 (77.1%), and 37 (80.4%) patients who received prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg, respectively, and by 37 (80.4%) patients who received placebo. A total of 11 patients discontinued study treatment owing to TEAEs during the treatment period and were from the prucalopride 1, 2, and 4 mg treatment groups (prucalopride 0.5 mg, n = 0; prucalopride 1 mg, n = 3 [6.3%]; prucalopride 2 mg, n = 2 [4.2%]; prucalopride 4 mg, n = 6 [13.0%]; placebo, n = 0). During the run-out period, TEAEs were reported by 18 (43.9%), 25 (55.6%), 26 (59.1%), and 27 (62.8%) patients in the prucalopride 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg groups, respectively, and by 28 (62.2%) patients in the placebo group. In all groups, the highest daily incidence of TEAEs occurred during the first 3 days of the treatment period.

| Adverse event, n (%) | Placebo | Prucalopride | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mga | 1 mg | 2 mg | 4 mga | ||

| DB period | n = 46 | n = 43 | n = 48 | n = 48 | n = 46 |

| Abdominal pain | 12 (26.0%) | 10 (23.3%) | 13 (27.1%) | 14 (29.2%) | 15 (32.6%) |

| Headache | 8 (17.4%) | 5 (11.6%) | 9 (18.8%) | 9 (18.8%) | 9 (19.6%) |

| Nausea | 4 (8.7%) | 3 (7.0%) | 7 (14.6%) | 13 (27.1%) | 10 (21.7%) |

| Flatulence | 13 (28.3%) | 3 (7.0%) | 4 (8.3%) | 7 (14.6%) | 7 (15.2%) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 4 (9.3%) | 6 (12.5%) | 10 (20.8%) | 11 (23.9%) |

| Constipation | 5 (10.9%) | 2 (4.7%) | 2 (4.2%) | 7 (14.6%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Sinusitis | 3 (6.5%) | 3 (7.0%) | 5 (10.4%) | 2 (4.2%) | 2 (4.3%) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 3 (7.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 5 (10.4%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| RO period | n = 45 | n = 41 | n = 45 | n = 44 | n = 43 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 6 (13.3%) | 6 (14.6%) | 9 (20.0%) | 6 (13.6%) | 9 (20.9%) |

| Flatulence | 11 (24.4%) | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (2.2%) | 4 (9.1%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Headache | 5 (11.1%) | 0 | 6 (13.3%) | 4 (9.1%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Constipation | 5 (11.1%) | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (2.2%) | 5 (11.4%) | 3 (6.9%) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | 6 (13.3%) | 4 (9.1%) | 1 (2.3%) |

- Abbreviations: CIC, chronic idiopathic constipation; DB, double-blind; RO, run-out; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

- a Not an approved dose of prucalopride.

Patients receiving prucalopride experienced more moderate to severe gastrointestinal TEAEs than patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal TEAEs considered possibly or definitely related to study drug were reported less often during the run-out period (n = 4–9 per group) than during the treatment period (n = 12–20 per group) for all groups, including placebo. There were no dose-related trends observed in the severity of TEAEs in patients receiving prucalopride. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported by one patient (2.2%) in the placebo group (neuritis; considered possibly related to study drug) and one patient (2.1%) in the prucalopride 1 mg group (diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting; all considered not related to study drug).

During the treatment period, TEAEs related to cardiovascular disorders were reported by five patients in the prucalopride groups (0.5 mg, n = 2 [4.7%]; 1 mg, n = 2 [4.2%]; 2 mg, n = 1 [2.1%]) and by one patient (2.2%) in the placebo group. In the run-out period, cardiovascular disorders were reported by seven patients in the prucalopride groups (0.5 mg, n = 3 [7.3%]; 1 mg, n = 2 [4.4%]; 2 mg, n = 1 [2.3%]; 4 mg, n = 1 [2.3%]) and by one patient (2.2%) who received placebo. During the treatment period, TEAEs related to psychiatric disorders were reported by five patients in the prucalopride groups (0.5 mg, n = 1 [2.3%]; 1 mg, n = 1 [2.1%]; 2 mg, n = 3 [6.3%]) and by four patients (8.7%) in the placebo group. In the run-out period, psychiatric disorders were reported by three patients in the prucalopride groups (1 mg, n = 1 [2.2%]; 2 mg, n = 2 [4.5%]) and by four patients (8.9%) who received placebo. Cardiovascular TEAEs were electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormal, ECG abnormal specific, heart murmur, and hypertension. Psychiatric TEAEs were agitation, anorexia, anxiety, appetite increased, depression, insomnia, and somnolence. Cardiovascular TEAEs in four patients and psychiatric TEAEs in five patients were considered possibly related to the study drug; however, none of these cardiovascular or psychiatric TEAEs were considered definitely related to the study drug.

3.4 Effect of re-treatment with prucalopride on efficacy parameters

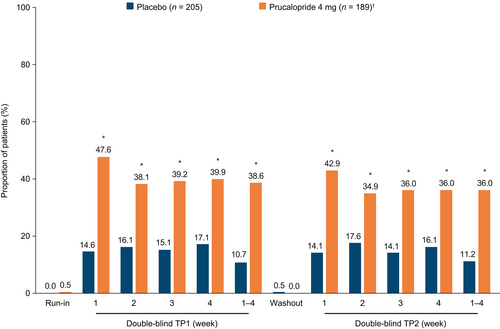

Of those who completed the study, most patients (total, 92.8% [387/417]; prucalopride, 93.6% [190/203]; placebo, 92.1% [197/214]) required only a 2-week washout period for their symptoms to recur and meet the criteria for CIC again. However, a minority (total, 7.2% [30/417]; prucalopride, 6.4% [13/203]; placebo, 7.9% [17/214]) required a 4-week washout period. Following the 2- or 4-week washout period in the phase 3 re-treatment trial, the proportion of responders in the second 4-week treatment period was 36.0% in the prucalopride 4 mg group and 11.2% in the placebo group. This was similar to the proportions in the first 4-week treatment period (prucalopride 4 mg, 38.6%; placebo, 10.7%), and was significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001) with prucalopride 4 mg than with placebo (Figure 3). Most responders in the first treatment period were successful in achieving response in the second treatment period; specifically, 52/73 patients in the prucalopride 4 mg group (71.2%) and 14/22 patients in the placebo group (63.6%). The findings for the EA population were consistent with the findings for the ITT population for treatment period 1 (weeks 1–4) and treatment period 2 (weeks 1–4) (Figure S2).

Use of bisacodyl was reported by 36 patients (14.2%) in the prucalopride 4 mg group and 42 patients (16.3%) in the placebo group. Average bisacodyl usage (number of 5 mg tablets taken per week) was similar during the first (prucalopride 4 mg, 0.8; placebo, 1.8) and second (prucalopride 4 mg, 1.0; placebo, 1.8) treatment periods.

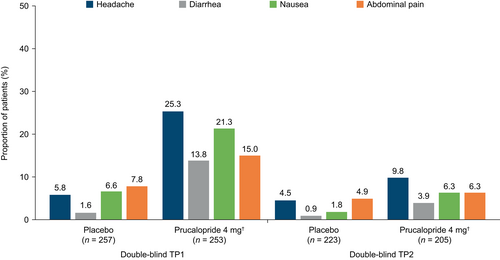

3.5 Effect of re-treatment with prucalopride on safety parameters

The incidence of TEAEs in the prucalopride and placebo groups in the first treatment period was 67.2% (n = 170) and 50.2% (n = 129), respectively, whereas in the second treatment period it was 44.9% (n = 92) and 38.1% (n = 85), respectively. Most TEAEs were considered mild or moderate in severity by the investigator. The most frequent TEAEs with prucalopride treatment (headache, diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain; ≥10% of patients in either treatment period) occurred at a lower frequency during the second treatment period than in the first treatment period in both groups (Figure 4). These TEAEs were most frequently reported on the first day of dosing in both treatment periods, were considered transient in nature, and resolved within that period. The incidence of cardiovascular disorders was low (≤2%) in each group during both treatment periods. TEAEs related to psychiatric disorders were reported at a lower frequency in the second treatment period (prucalopride 4 mg, n = 3 [1.5%]; placebo, n = 1 [0.4%]) than in the first treatment period (prucalopride 4 mg, n = 11 [4.3%]; placebo, n = 13 [5.1%]).

Most of the TEAEs that were assessed as at least possibly related to study medication were gastrointestinal or nervous systems disorders (Table 3). TEAEs considered very likely to be related to study medication that occurred in more than one patient in the prucalopride group during the first treatment period were headache (n = 11 [4.3%]), diarrhea (n = 10 [4.0%]), nausea (n = 6 [2.0%]), abdominal pain (n = 6 [2.4%]), and flatulence (n = 2 [0.8%]). Apart from one case each (0.5%) of diarrhea and headache, no TEAEs with a very likely drug relationship were reported in the prucalopride group during the second treatment period.

| Adverse event, n (%) | Placebo | Prucalopride 4 mgb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP1 (n = 257) | TP2 (n = 223) | TP1 (n = 253) | TP2 (n = 205) | |

| Headache | 12 (4.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 61 (24.1%) | 12 (5.9%) |

| Nausea | 8 (3.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | 45 (17.8%) | 8 (3.9%) |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (5.1%) | 4 (1.8%) | 31 (12.3%) | 8 (3.9%) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 31 (12.3%) | 4 (2.0%) |

| Flatulence | 9 (3.5%) | 5 (2.2%) | 15 (5.9%) | 3 (1.5%) |

| Vomiting | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 9 (3.6%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Dizziness | 3 (1.2%) | 0 | 9 (3.6%) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 6 (2.4%) | 3 (1.5%) |

| Fatigue | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Appetite increased | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.6%) | 0 |

- Abbreviations: CIC, chronic idiopathic constipation; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; TP, treatment period.

- a TEAEs assessed as at least possibly related to study medication by the investigator.

- b Not an approved dose of prucalopride.

The predominant TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation were diarrhea, nausea, headache, and abdominal pain. A total of 27 patients discontinued study drug owing to TEAEs during the first (prucalopride 4 mg, n = 17 [6.7%]; placebo, n = 5 [1.9%]) and second (prucalopride 4 mg, n = 1 [0.4%]; placebo, n = 4 [1.8%]) treatment periods. SAEs were reported by five patients (1.9%) in the prucalopride group (individual SAEs were: abdominal pain, abortion, hypokalemia, menstrual disorder, supraventricular tachycardia, unintended pregnancy, vaginal hemorrhage, and varicella) and by four patients (1.6%) in the placebo group (individual SAEs were: allergic reaction, neuropathy, surgical intervention, uterovaginal prolapse, and uterine disorder [not otherwise specified]). All SAEs were considered unlikely to be related to study medication, except for an allergic reaction in one patient in the placebo group that was considered probably related.

4 DISCUSSION

Clinical use of prucalopride in patients with CIC is well established, and the efficacy and safety of prucalopride have been investigated in several studies over the past 20 years. These include six double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter clinical trials (between 1998 and 2013)15 that led to the FDA approval of prucalopride for adults with CIC in 2018,13 indicating the clinical relevance and acceptance of the data from these studies. Although the phase 2 dose-finding and phase 3 re-treatment trials were conducted almost two decades ago, we believe the findings from these studies are clinically meaningful, considering data on prucalopride treatment patterns in patients with CIC are currently lacking. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis investigating the effects of prucalopride treatment cessation and re-treatment in adults with CIC. Data from a phase 2 dose-finding trial demonstrated that cessation of prucalopride use after a 4-week treatment period resulted in a loss of clinical effect within 1 week from the last dose, with a reduction in the mean number of CSBMs per week to levels similar to those at baseline or in individuals receiving placebo. The timeframe for this loss of clinical effect is in line with the pharmacokinetics of prucalopride, which has a terminal half-life of approximately 1 day.21 In the 4 weeks following treatment cessation, the frequency of TEAEs was similar in individuals who had received prucalopride or placebo. Patients in the phase 3 re-treatment trial could requalify during the 2-week or 4-week washout period following symptom recurrence. It should be noted that in order to requalify, patients had to meet stringent inclusion criteria for CIC, which may not be reflective of the real-world situation. In the phase 3 re-treatment trial, the majority of patients (~93%) only required a 2-week washout period in both treatment groups for their symptoms to recur. It is unclear why patients relapse at different rates, but factors including baseline disease severity may be a contributing factor; investigating predictors of relapse would be informative. Following re-initiation of treatment after the 2-week or 4-week washout period, the efficacy of prucalopride was largely similar between treatment period 1 and treatment period 2. More than 70% of patients who initially responded to prucalopride demonstrated the ability to respond again upon re-initiating treatment.

These clinical trial data provide information relevant to the treatment of patients with CIC in a real-world setting, where it is not uncommon for patients to start and stop medications intermittently. A study of real-world pharmacotherapy patterns for prosecretory agents in patients with CIC in the United States (2013–2015) found that early discontinuation was common, with most patients receiving linaclotide or lubiprostone treatment for less than 6 months.22 The study did not investigate the reasons for treatment discontinuation, but given that symptoms of CIC can present intermittently, patients may discontinue, and re-initiate therapy over time.9, 17, 22

Discontinuation of prescribed CIC treatment is often related to TEAEs such as diarrhea, with these side effects having a significant impact on individuals' daily lives and, consequently, treatment satisfaction.6 In the current analysis, TEAEs were predominantly gastrointestinal in nature, in agreement with previous studies of prucalopride.15 Fewer TEAEs were reported during re-treatment with prucalopride than during initial treatment in the phase 3 re-treatment trial, suggesting that patients who restart therapy may be less likely to experience side effects than those initiating treatment for the first time. In the re-treatment study, the washout period was either 2 weeks or 4 weeks in duration; further research is needed to determine if these results are replicated with a longer treatment break.

TEAEs associated with prucalopride were mostly transient and primarily occurred on the first day of dosing in each treatment period. This pattern has been reported in other phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg in patients with CIC.11, 23 In those phase 3 trials, incidences of the most frequently reported TEAEs (headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea) were similar between prucalopride and placebo groups when events that occurred on day 1 of treatment were excluded from analyses.11, 23 This may be a key clinical consideration for patients who need to pause their treatment for a period of time for any number of reasons.

In both trials analyzed here, the proportion of responders was significantly higher with prucalopride 2 mg or 4 mg once daily than with placebo. In the phase 2 dose-finding study, the prucalopride 2 mg and 4 mg doses were selected for investigation in subsequent studies. These results are consistent with findings from other clinical trials of prucalopride in adults with CIC.15 Further research is warranted to investigate if there are common characteristics among the patients who responded to prucalopride in both the first and second treatment periods of the phase 3 re-treatment trial.

The use of data from randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials is a key strength of this analysis. These data are potentially relevant to the use of prucalopride in clinical practice, where clinicians may encounter patients who stop and restart treatment intermittently. However, this investigation has several limitations. The two clinical trials were conducted more than 20 years ago, in 1996–1997 and 1999–2000. Therefore, these studies could not leverage the merits of modern data collection techniques or the most up-to-date Rome IV criteria24 for diagnosing functional constipation. The treatment and run-out/washout periods examined were relatively short in duration (up to 4 weeks); therefore, longer trials are warranted to determine if the responses seen with re-treatment are sustained with extended washout periods. Furthermore, the phase 3 re-treatment trial did not include the prucalopride dose currently approved in the United States (2 mg or 1 mg once daily),13 and real-world studies are needed to inform understanding of prucalopride treatment patterns. Additional limitations include potential inaccuracies with patient-reported daily diaries and that our findings may not be generalizable to patients with other subtypes of constipation.

In conclusion, data from randomized controlled trials in adults with CIC demonstrate that the clinical effect of prucalopride is diminished within 1 week of treatment cessation. However, findings from this analysis demonstrated that with re-initiation of treatment after a 2-week or 4-week washout period, the efficacy and safety of prucalopride are maintained.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jimmy Hinson, Heinrich Achenbach, Brian Terreri and Mena Boules contributed to the manuscript concept, data interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript to be published/revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank René Kerstens of Orion Statistical Consulting BV, Hilvarenbeek, Netherlands who performed statistical analyses for this study, funded by Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Inc., a Takeda company. The clinical trials included in this study were funded by Janssen and Movetis. This analysis was funded by Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Inc., a Takeda company. Medical writing support was provided by Sarah Graham, MSc, PhD, and Sandra Cheriyamkunnel, MSc, of PharmaGenesis London, London, UK, and funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Jimmy Hinson, Brian Terreri, and Mena Boules are employees of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., and stockholders of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. Heinrich Achenbach was an employee of Takeda at the time of the study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data sets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants' data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months from initial request to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection and requirements for consent and anonymization.