Efficacy of Breast Crawling on Breastfeeding Outcomes, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Anxiety Status After Term Vaginal Birth: A Randomized Controlled Trial

ABSTRACT

Breast crawl technique is a strategy for initiating breastfeeding immediately after delivery. This study evaluated the effects of breast crawl on neonatal feeding style, knowledge, attitudes, and anxiety levels of breastfeeding through a single-center randomized controlled trial. A total of 295 mother-infant pairs were recruited and randomly divided into the breast crawl group (n = 149) and the conventional skin-to-skin contact group (n = 146). Compared with the conventional skin-to-skin contact group, the breast crawl group had higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding at 24 h (65.1% vs. 15.8%, p < 0.001), day 3 (58.4% vs. 24.7%, p = 0.005), month 1 (57.7% vs. 45.9%, p = 0.025), and month 6 (47.0% vs. 11.6%, p < 0.001), higher BAT scores (11.00 vs. 9.00, p = 0.001), higher success rates of first breastfeeding (93.3% vs. 82.9%, p = 0.006), shorter time for the onset of lactogenesis stage II (23.65 vs. 49.38, p < 0.001), more stable forehead skin temperature within 2 h of birth, and improved maternal anxiety (38.75 vs 41.88, p < 0.001) and breastfeeding attitudes (59.00 vs. 57.00, p < 0.032) on the first day postpartum. There was no statistically significant difference in breastfeeding knowledge (89.00 vs. 89.00, p < 0.909) between the two groups on the first day postpartum. This study demonstrated that breast crawling has a positive effect on increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates and neonatal thermoregulation, reducing maternal anxiety levels, and improving feeding attitudes.

Trial Registration

ChiCTR2500099756.

Summary

-

This study validated the clinical application efficacy of breast crawl (BC) in breastfeeding.

-

The BC intervention may help to increase the exclusive breastfeeding rate, improve breastfeeding success rates, shorten the time for onset of lactogenesis stage II, stabilize neonatal forehead skin temperature, and reduce maternal anxiety levels while improving breastfeeding attitudes.

-

The intervention had no significant effect on the mastery of breastfeeding knowledge.

-

Future intervention programs should extend the intervention and follow-up periods to investigate the long-term effects of BC on mothers and infants.

1 Background

Breastfeeding is regarded as the optimal source of nutrition for infants, and the initial hours following birth are crucial for establishing breastfeeding and offering support (World Health Organization 2018; NEOVITA Study Group 2016). Breastfeeding promotes healthy brain development and is crucial for preventing the triple burden of malnutrition, infectious diseases, and mortality while also reducing the risk of obesity and chronic diseases later in life (Pérez-Escamilla et al. 2023). It is estimated that suboptimal breastfeeding leads to national economic losses of $302 billion annually, due to the unrealized benefits of breastfeeding for health and human development (Walters et al. 2019). The benefits of breastfeeding have been widely recognized, and the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommend that infants should initiate and establish breastfeeding in the first hours and days of live and be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months (World Health Organization 2018). However, a survey study revealed that in China, the proportions of live births who initiate breastfeeding within 1 h, between 1 and 12 h, and between 12 and 24 h after delivery were only 51.4%, 28.3%, and 2%, respectively, and the rate of exclusive breastfeeding among infants aged 0-5 months was merely 36.2%, which was lower than the global average (Nutrition Society of China, Subcommittee on Maternal and Child Nutrition 2022). The American Academy of Pediatrics advises that all healthy infants should maintain skin-to-skin contact with their mothers until the initial feeding takes place (Hubbard and Gattman 2017). As early as 1998, Klaus introduced the concept of breast crawl (Klaus 1998), and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommended breast crawl as the preferred approach for initiating breastfeeding (UNICEF and Gangal 2007). Nevertheless, domestic research on this topic is still in its initial stage.

Breast crawl (BC) is considered an instinctive response in newborns and is an integral process of natural lactation in mothers and instinctive breast seeking in newborns (UNICEF and Gangal 2007). The practice of breast crawl involves, in the absence of medical necessity, placing newborns on the mother's torso for skin-to-skin contact without interference, enabling the newborn to autonomously move towards the mother's breast to locate and self-attach for initial feeding (UNICEF and Gangal 2007). Studies have demonstrated that newborns can exhibit a series of predictable breast-seeking behaviours during the process of breast crawling by coordinating perception and motor senses, including birth crying, relaxation, awakening, activity, crawling, resting, familiarization, sucking, and sleeping (Brimdyr et al. 2020; Cui et al. 2020). These nine predictable behavioural patterns support the transition of infants from intrauterine life to extrauterine life and establish breastfeeding (Widström et al. 2020). It can also encourage the establishment of a lactation cycle in the mother, extend lactation time, and increase the rate of breastfeeding (Cheng et al. 2022). Moreover, breast crawling during the first hour after birth not only enhanced immediate outcomes, such as reducing pain from episiotomy suturing and decreasing blood loss during childbirth (Rana and Swain 2023) but also promoted the establishment of lasting microbiota in newborns over extended periods (Kim et al. 2019). Simultaneously, early contact can foster the bond between newborns and their mothers, enhancing the child's personal adaptability and versatility of their growth and development (Mendu et al. 2024). However, despite the numerous benefits of breast crawl, it has not been widely adopted in clinical practice for various reasons (Girish et al. 2013). The reasons may included postpartum labour ward practices (such as umbilical cord clamping, cleaning and measuring the baby, administering vitamin K injections, and the timing of episiotomy repair) that hindered early maternal-infant skin-to-skin contact (Girish et al. 2013; Pang et al. 2020); second, the varying degrees of acceptance of the breast crawl by mothers and families; and third, a high volume of births and a high utilization rate of delivery beds led medical staff to generally believe that implementing breastfeeding increased their workload (Pang et al. 2020).

Furthermore, studies have shown that factors such as the stable temperature gradient of newborn skin (Zanardo et al. 2017), the high maternal acceptance of breastfeeding information (Duchsherer et al. 2024), reduced levels of maternal anxiety (Nisar et al. 2024), and positive attitudes towards breastfeeding (von Ash et al. 2023) could all have contributed to promoting breastfeeding. However, to date, few studies have investigated whether newborn breast crawl affects these outcomes (Morns et al. 2022).

The principal aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of breast crawl in improving exclusive breastfeeding, enhancing maternal knowledge about breastfeeding, changing attitudes towards breastfeeding, and altering anxiety states.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

A randomized clinical trial was conducted at the Women and Children's Hospital affiliated with Xiamen University between December 2022 and November 2023.

2.2 Ethical Consideration

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Women and Children's Hospital of Xiamen University (No. KY-2022-060-K01). At least one parent must have signed the informed consent for inclusion for each newborn in the study before the start of and/or in the latent phase of labour and before randomization. The trial received no commercial funding.

2.3 Study Population

Full-term newborns, with born from a single gestation and by vaginal birth, and whose mothers were aged from 20 to 45 years old, with normal breast development, and intended to breastfeed were included. Neonates who required medical intervention at birth, mother‒child pairs with breastfeeding contraindications, and mothers with severe perinatal complications or comorbidities were excluded.

2.4 Sample Size

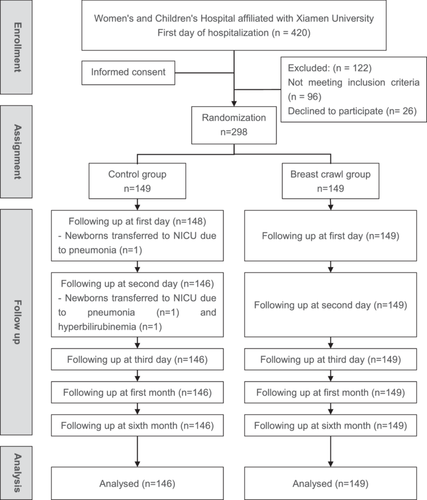

The sample size was calculated on the basis of the literature (Xuemei et al. 2021), reporting a breastfeeding rate at discharge of 58.00% in the experimental group and 37.5% in the control group. The sample size ratio between the experimental and control groups was 50:48. With a power of 90%, an alpha error of 5%, and a two-tailed calculation, the sample size was determined via the calculation website (http://www.powerandsamplesize.com/). Assuming a follow-up loss of 20%, a total of 298 mother-child pairs are needed, 149 in each group.

2.5 Randomization and Masking

The mother‒child pair was randomly assigned to one of two study groups: intervention (breast crawling) or control (routine skin-to-skin contact). A random number table method was used to generate a random sequence, and the subjects with odd numbers were assigned to the intervention group, while even numbers were assigned to the experimental group. The allocation numbers were kept hidden in opaque and sealed envelopes and revealed during the second stage of maternal delivery. Owing to the characteristics of the intervention, blinding could not be applied to researchers who performed interventions and collected data, and it was only applied to those who analyzed the data.

2.6 Outcomes

The sociodemographics of all the participants were collected. For the primary objective, the neonatal feeding style were assessed at 24 h, 3 days, 1 month, and 6 months postpartum. Additionally, the participants' anxiety, knowledge and attitudes toward breastfeeding were measured on the 2 days postpartum. For secondary objectives, the skin temperatures of newborns at 30 min, 1 h, and 2 h after birth, the success of breastfeeding, and the time of lactation initiation were evaluated. All the aforementioned data were gathered from women's health records, questionnaires, and telephone interviews. According to the WHO definition, exclusive breastfeeding is defined as feeding only breast milk without any other liquids or solids, except for vitamin and mineral supplements or medications (World Health Organization 1991).

Breastfeeding knowledge was measured via the Breastfeeding Knowledge Questionnaire (BKQ). The content validity index of the BKQ is 0.91, and the Cronbach's α coefficient is 0.820 (Zhang 2022). This tool has two dimensions related to the advantages of exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding techniques, with 25 items, and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The total score ranges from 25 to 125; all the entries are positively scored, and higher scores indicate a more comprehensive understanding of breastfeeding knowledge.

Breastfeeding attitudes were measured via the Chinese version of the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS), which has undergone rigorous translation and validation (Dai and Liu 2013). The content validity of the IIFAS is 0.71, and the Cronbach's α coefficient is 0.635. The tool has 17 items, 9 of which require reverse scoring, and uses a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, resulting in a total score ranging from 17 to 85. A higher score indicates a better attitude towards breastfeeding.

The anxiety of women 24 h after childbirth was measured via the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (Wang et al. 1999). The tool has 20 items, with items 5, 9, 13, 17, and 19 being reverse-scored, whereas the remaining 15 items are positively scored, and a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 is used, resulting in a total score ranging from 20 to 80. Higher scores indicate a higher level of anxiety for an individual. After the self-rating was completed, the scores of all 20 items were totalled to a raw score, which was then converted into a standard score by multiplying by 1.25.

Breastfeeding success was measured via the Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BAT), which encompasses four distinct dimensions: feeding timing, feeding initiation, sucking proficiency, and nipple attachment. The tool uses a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with a total score of 8 or higher signifying successful breastfeeding. This tool boasts impressive reliability and validity, with a Cronbach's α of 0.91 (Carfoot et al. 2005) and a retest Cronbach's α of 0.97 (Gao et al. 2010). The formula for calculating breastfeeding success rates is as follows: the number of successful breastfeeding cases divided by the sample size, multiplied by 100%.

2.7 Intervention

The intervention group adopted breast crawling. Before the intervention, an intervention team was set up to clarify roles and tasks. The head nurse trained team members on safety and neonatal breast crawling. The midwives handled baby reception, wiping, and delayed umbilical cord cutting. Researchers have educated pregnant women on breast crawling and proper posture/protection. During this time, no intervention was made to ensure smooth and safe progress of the experiment. In accordance with the BC website of the United Nations Children's Fund (http://www.breastcrawl.org/), after childbirth, newborns were immediately cleaned with a towel (without wiping their hands first), and a newborn assessment score was recorded. Newborns were subsequently placed in a prone position on the mother's abdomen, with their heads between breasts, eyes level with the nipple, faces turning to one side, and toes touching the mother's symphysis pubis. Their arms and legs were curved in a natural “frog-like” position. The mother supported the baby with one hand on the newborn's back and the other hand under the newborn's feet. Newborns should be given enough time to reach the nipple independently and complete at least one effective sucking. After 90 min, the midwives provided routine care measures, including weighing and dressing, and subsequently positioned the newborns on the side of their mothers.

The control group followed the Expert Consensus on Early Essential Newborn Care (China, 2020) (Perinatology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, Obstetrics and Gynecology Branch of the Chinese Medical Association, Obstetric Nursing Committee of the Chinese Nursing Association 2020) for conventional care. After the respiratory tract secretions were cleared, the newborns were placed on a radiant warmer for late cord clamping, drying, weighing, foot printing, wristband application, and dressing with a hat. After the placenta was delivered and the birth canal was managed, approximately 30 min post-birth, the newborns were placed beside their mothers in a side-lying position, with their cheeks closed to the nipple for 90 min of skin-to-skin contact. Once newborns exhibited rooting reflex, mothers assisted them to latch onto the nipple for breastfeeding more quickly by bringing the nipple close to the infants' mouth.

During the intervention, both groups of newborns were monitored via pulse oximeters, axillary temperature measurements, and continuous medical surveillance. Mothers were advised and supported to initiate breastfeeding in the first hour after birth.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

All the collected data were coded, input into Excel spreadsheets, and cleaned, and the missing values were verified. The Excel data tables were imported into SPSS version 27.0 statistical software. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were employed to analyse the data in accordance with the research objectives. The means, standard deviations, and frequency percentages were used to describe demographic characteristics. Unpaired t-tests, χ2 tests, and Fisher's exact tests were employed to compare maternal and infant outcomes between the study and control groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 with all tests being two tailed.

3 Results

A total of 295 mother-child pairs were included, 149 (50.5%) in the BC group and 146 (49.5%) in the control group (Figure 1). Three participants in the BC group were lost to follow-up for the outcome of exclusive breastfeeding due to neonatal pneumonia and hyperbilirubinemia, with no difference in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 1).

| Breast crawl group (n = 149) | Control group (n = 146) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age, years (median − IQR) | 31.00 (29.00−34.00) | 32.00 (28.75−34.00) | 0.541 |

| Height, metres (median − IQR) | 1.60 (1.58−1.64) | 1.60 (1.56−1.63) | 0.132 |

| BMI beginning of pregnancy (median − IQR) | 20.63 (19.03−22.41) | 20.48 (19.23−22.91) | 0.490 |

| BMI the day before delivery (median − IQR) | 25.36 (23.28−27.39) | 25.25 (23.65−27.05) | 0.590 |

| Educational level n (%) | 0.986 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 22 (14.8) | 21 (14.4) | |

| High school and colleges | 17 (11.4) | 16 (11.0) | |

| University and above | 110 (73.8) | 109 (74.7) | |

| Working n (%) | 0.867 | ||

| Yes | 111 (74.5) | 110 (75.3) | |

| No | 38 (25.5) | 36 (24.7) | |

| Average monthly household income n (%) | 0.685 | ||

| <¥5000 | 20 (13.4) | 24 (16.4) | |

| ¥5000~¥10,000 | 83 (55.7) | 82 (56.2) | |

| >¥10,000 | 46 (30.9) | 40 (27.4) | |

| Place of residence n (%) | 0.636 | ||

| City | 115 (77.2) | 116 (79.5) | |

| Village | 34 (53.1) | 30 (20.5) | |

| Undergone breast surgery n (%) | 0.088 | ||

| Yes | 6 (4.0) | 13 (8.9) | |

| No | 143 (96.0) | 133 (91.1) | |

| Epidural for labour pain n (%) | 0.990 | ||

| Yes | 104 (69.8) | 102 (69.9) | |

| No | 45 (30.2) | 44 (30.1) | |

| Newborn characteristics | |||

| Sex n (%) | 0.504 | ||

| Male | 68 (45.6) | 61 (41.8) | |

| Female | 81 (54.4) | 85 (58.2) | |

| Birthweight, grams (mean ± SD) | 3191.30 ± 342.14 | 3258.29 ± 367.73 | |

| Gestational age, weeks (median − IQR) | 39.43 (38.86−40.00) | 39.29 (38.57−40.14) |

Differences were observed between the two groups in the percentage of breastfeeding at 24 h (p < 0.001), at 3 days (p = 0.005), at 1 month (p < 0.001), and at 6 months (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, variations were observed in breastfeeding attitudes (IIFAS scores) and anxiety levels (SAS scores) on the second day postpartum (Table 2).

| Breast crawl group (n = 149) | Control group (n = 146) | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal feeding style 24 h n (%) | 78.414 | < 0.001* | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 97 (65.1%) | 23 (15.8%) | ||

| Mixed Feeding | 50 (33.6%) | 123 (84.2%) | ||

| Bottle feeding | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Neonatal feeding style 3 day n (%) | 34.547 | 0.005* | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 87 (58.4%) | 36 (24.7%) | ||

| Mixed Feeding | 60 (40.3%) | 107 (73.3%) | ||

| Bottle feeding | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (2.1%) | ||

| Neonatal feeding style 1 month n (%) | 7.403 | 0.025* | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 86 (57.7%) | 67 (45.9%) | ||

| Mixed Feeding | 61 (40.9%) | 70 (47.9%) | ||

| Bottle feeding | 2 (1.3%) | 9 (6.2%) | ||

| Neonatal feeding style 6 month n (%) | 44.312 | < 0.001* | ||

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 70 (47.0%) | 17 (11.6%) | ||

| Mixed feeding | 61 (40.9%) | 101 (69.2%) | ||

| Bottle feeding | 18 (12.1%) | 28 (19.2%) | ||

| BAT (median − IQR) | 11.00 (9.50−12.00) | 9.00 (8.00−11.00) | 7542.000 | 0.001* |

| BAT n(%) | 7.645 | 0.006* | ||

| No | 10 (6.7%) | 25 (17.1%) | ||

| Yes | 139 (93.3%) | 121 (82.9%) | ||

| Time for the onset of lactogenesis stage II, hours | 23.65 (7.57−49.00) | 49.38 (23.99−57.64) | 14,978.500 | < 0.001* |

| Newborn's temperature (°C) | ||||

| 30 min | 36.50 (36.30−36.90) | 36.70 (36.50−37.00) | 14,013.000 | < 0.001* |

| 1 h | 36.75 (36.50−37.00) | 36.90 (36.70−37.10) | 13,347.500 | < 0.001* |

| 2 h | 36.70 (36.50−36.80) | 36.60 (36.60−36.80) | 11,013.000 | 0.850 |

| SAS (median − IQR) | 38.75 (32.50−43.75) | 41.88 (36.25−46.25) | 13,231.000 | < 0.001* |

| IIFAS (median − IQR) | 59.00 (55.00−64.00) | 57.00 (53.00−62.00) | 9308.000 | 0.032* |

| BKQ (median − IQR) | 89.00 (85.00−94.00) | 89.00 (83.75−95.00) | 10,960.500 | 0.909 |

- Note: BAT: the Breastfeeding Assessment Tool; BKQ: the Breastfeeding Knowledge Questionnaire; IIFAS: the Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale; SAS: the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.

- * Significant at 0.05.

Similarly, there were differences in the time of lactation onset between the two groups of mothers, as well as in the body temperature of newborns at 30 min and 1 h after birth (Table 2). However, no differences were found in breastfeeding knowledge (BKQ scores) on the second day postpartum or the body temperature of newborns at 2 h after birth (Table 2).

4 Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, it was found that breast crawl could improve outcomes of breastfeeding, including an increase in the rate of exclusive breastfeeding, an increase in the success rate of breastfeeding, a reduction in the time to initiate breastfeeding, and a decrease in the SAS score on the second day as well as the IIFAS score. The skin temperature gradient in newborns may have facilitated mother–infant thermal identification and communication during the breast crawl from birth to the initiation of breastfeeding. In this study, although no difference was observed between the groups in terms of the skin temperature of the newborns at the second hour postpartum, the temperature was maintained at a more stable level during breast crawl than during conventional skin-to-skin contact. Moreover, no differences in BKQ scores were observed between the groups.

Breast crawl not only facilitates the neonatal transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life, enhances infant security, and rapidly establishing maternal-infant bonding, but also promotes maturation of the rooting reflex and stimulates the release of oxytocin and prolactin, thereby improving the success rate of initial breastfeeding (Zhong et al. 2020; Xia and Shao 2022). Our previous study found that breast crawl contributes to improved rates of successful initial breastfeeding, as well as the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at discharge and at 6 months postpartum (Huang and Chen 2025). This study revealed that compared with conventional skin-to-skin contact, breast crawl is more effective at promoting breastfeeding, including the success rate of first breastfeeding and the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for up to 6 months. Specifically, it not only improved the BAT score and percentage of infants successfully breastfeeding for the first time but also increased the percentage of infants receiving exclusive breastfeeding at 24 h, 3 days, 1 month, and 6 months postpartum. Studies have indicated that compared to the routine care group, infants who have skin-to-skin contact occurred immediately with their mothers after birth have been proven to exhibit more efficient sucking patterns (Righard and Alade 1990), with a higher rate of successful breastfeeding initiation (Aghdas et al. 2014) and the duration of exclusive breastfeeding that can last for 3 months or longer (Prian-Gaudiano et al. 2024). However, some studies have shown that newborns who only engaged in skin-to-skin contact and passively accepted the nipple were prone to rejecting the breast and nipple, which could lead to the failure of breastfeeding (Fan et al. 2021; Svensson et al. 2013). Pang et al. (2023) reported that newborns who successfully completed breast crawling initiated breastfeeding earlier and sustained it for a longer duration compared to those in the failure group, which further confirmed our research findings.

Our trial also revealed that the percentage of exclusive breastfeeding remained relatively stable in the breast crawl group, whereas it significantly increased to 45.9% in the conventional skin contact group by the first month. Agudelo et al. (2021) reported that regardless of the timing of initial mother–infant skin-to-skin contact, it can increase the proportion of infants who are exclusively breastfed during the first 6 months.

The current trial revealed a significant difference in the time of lactation initiation, with women who underwent breast crawling initiating sooner than those in the contact group did, which was consistent with previous research findings on breast crawling (Rana and Swain 2023; Pang et al. 2023; Spatz et al. 2024). This study also found that newborns in the breast crawling group had more stable fluctuations in skin temperature within 2 h after birth than did those in the conventional group. Limited research suggests that the temperature gradient on newborn skin could facilitate maternal–infant thermal identification and communication during the natural progression from breast crawling to breastfeeding (Zanardo et al. 2017). Notably, the thermal features of the areola are triggered by crying infants, which can regulate the local evaporation rate of odours, and thermal and olfactory signals assist newborns in locating the nipple, thus providing optimal conditions for the smooth progression of breast crawling (Vuorenkoski et al. 1969; Hym et al. 2021).

The present study showed that, on the newborn's first day of life, mothers in the breast-crawl group exhibited an improvement in their breastfeeding attitudes and a reduction in anxiety levels. A Study have indicated that breastfeeding attitudes was predictor of breastfeeding behaviour during the first 2 months postpartum, and a more positive breastfeeding attitude could promote postpartum breastfeeding behaviour and prolong breastfeeding duration (Han et al. 2023). Lower levels of anxiety, on one hand, positively affected maternal-child interactions and breastfeeding by enhancing maternal self-esteem; on the other hand, it alleviated maternal stress, promoted the release of oxytocin, and had a positive impact on the physiological processes of the milk ejection reflex and breastfeeding, thereby facilitating the success of breastfeeding (Hoff et al. 2019). Zanardo Zanardo et al. (2017) reported that a positive attitude and reduced psychological stress could, to a certain extent, have contributed to the maintenance of stable breast temperature and promote milk production, thereby facilitating the success of breastfeeding, which was consistent with the results of this study. Cui and Wang (2024) found that breast crawling positively impacts postpartum depression improvement, exclusive breastfeeding rate enhancement, and reduction in lactation initiation time. Despite targeted breastfeeding health education provided to mothers in the breast crawl group, the results of the present study still revealed that the breastfeeding knowledge of both groups was at a moderate level, and there was no significant difference between them during hospitalization, as evaluated by the BKQ, which may be related to the fact that most women were provided with information about breastfeeding by the hospital (Ragusa et al. 2020). In contrast to our findings, Zhong and Lü (2021) observed that breast crawl can not only effectively enhance maternal psychological resilience but also effectively improve breastfeeding knowledge and skills. A cohort study indicated that a positive attitude and psychological state towards breastfeeding were related to an increased likelihood of breastfeeding at 4 months and even at 6 months, while the universalization of breastfeeding knowledge was not associated with maintaining exclusive breastfeeding or any of the investigated postnatal feeding practices (Ragusa et al. 2020; Naja et al. 2022), which further supports the findings of this study.

This study had several limitations. First, we did not monitor the occurrence and duration of sequential movements during the breast crawl, which could affect lactation, newborn skin temperature, or maternal psychological emotional changes. Second, the follow-up intervals for the second and third rounds of exclusive breastfeeding were excessively long, potentially compromising the timeliness of the research data, which could also be considered another study limitation. Finally, all participants were recruited from the obstetrics department of a single hospital. Cultural and background factors may limit the generalizability of findings to other types of hospitals and other countries.

5 Conclusions

The results of exclusive breastfeeding among newborns in the first 6 months in the breast crawl group showed significant improvement, as did the mothers attitudes towards breastfeeding and their levels of anxiety. This study found that women who received breast crawling felt more breast fullness before feeding and their newborns slept more quietly and steadily between feedings. However, it is regrettable that we failed to quantify milk production difference in a timely fashion. Future research could further evaluate milk production volume and infant sleep to provide a scientific basis for the clinical practice of breast crawling. Given the current situation of low rates of exclusive breastfeeding and the low prevalence of breast crawl, healthcare institutions should implement standardized the breast crawl interventions during hospitalization, including educating women about the importance of breastfeeding and conducting the breast crawl after delivery for full-term infants, to increase clinical decision-making that support exclusive breastfeeding and continue the breast crawl after discharge. Additionally, a continuous care model that leverages the “Internet+” tripartite linkage of “hospital-community-family” can be adopted to empower these them and increase the overall breastfeeding rate.

Author Contributions

Huang Lingling: responsible for research design, data collection, and the execution of clinical trials. Chen Fan: contributed to research design, conducted data analysis, and authored the paper. He Hongyu: interpreted data, revised, and reviewed the paper. Huang Yinying: conducted clinical trials, collected data, and coordinated project activities. Lu Meidan: assisted with clinical trials and organized data. Lin Qiaoli, Li Linghong, Yang Bifeng, and Xie Yuezhen: participated in clinical trials, and were involved in data collection and organization.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the mothers and newborns who participated in this study, as well as the Xiamen Maternal and Child Health Hospital. Research funded by the Nursing Association of Xiamen City (XMSHLXH2306).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Science Data Bank at https://www.scidb.cn/en/anonymous/SUpKbnll.