Perceived social status, socioeconomic status, and preventive dental utilization among a low-income Medicaid adult population

Abstract

Objectives

Perceived Social Status (PSS) is a measure of cumulative socioeconomic circumstances that takes perceived self-control into account. It is hypothesized to better capture social class compared to socioeconomic status (SES) measures (i.e., education, occupation, and income). This study examined the association between PSS and dental utilization, comparing the strength of associations between dental utilization and PSS and SES measures among a low-income adult Medicaid population.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was administered to a random sample of low-income adults in Iowa, United States with Medicaid dental insurance (N = 18,000) in the spring of 2018. Respondents were asked about PSS, dental utilization, and demographics. A set of multivariable logistic regression models examined the relative effects of PSS and SES measures on dental utilization, controlling for age, sex, health literacy, whether the respondent was aware they had dental insurance, transportation, and perceived need of dental care.

Results

The adjusted response rate was 25%, with a final sample size of 2252. Mean PSS (range 1–10) was 5.3 (SD 1.9). PSS was significantly associated with dental utilization (OR = 1.11; CI = 1.05, 1.18) when adjusting for control variables, whereas other SES measures—education, employment, and income—were not.

Conclusions

PSS demonstrated a small positive association with dental utilization. Results support the relative importance of PSS, in addition to SES measures, as PSS may capture aspects of social class that SES measures do not. Results suggest the need for future research to consider the effects of PSS on oral health outcomes and behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

Perceived Social Status (PSS) refers to the self-perception of one's status in the social hierarchy relative to other individuals and accounts for variation in life experiences [1, 2]. PSS differs from other measures of socioeconomic status (SES), such as income and employment, which are objective and only capture aspects of social status at a fixed time point. In contrast, PSS measures one's perception of their location on the social class ladder and allows for cognitive averaging of life events and their impacts on social class [3]. As a construct, it extends beyond traditional measures of SES to account for individual perceptions regarding past, present, and future financial resources; social and economic prospects; self-efficacy; personal health; and perceived personal control [2, 4, 5]. PSS is assessed by asking individuals to consider education, occupation, and income of others in the United States and to select their relative position on the “social ladder” using a scale of 1–10 [3, 6].

Previous studies have documented that PSS contributes unique variance in the prediction of self-reported oral health [7, 8] and health promoting behaviors, including healthy dietary choices [9]. Perceived control, an individual's perceived ability to achieve positive outcomes or avoid consequences through personal actions based on skill, available resources, and opportunities, may explain this relationship [2, 5, 10]. Perceived control has been identified as a predictor of health behavior. Low perceived control can lead to indifference and reduced efforts to perform healthy behaviors [11]. An increased sense of perceived control could facilitate oral health-promoting behaviors by increasing the desire to take care of one's oral health. For example, higher perceived control has been associated with routine dental utilization [12, 13]. Long-term routine dental utilization contributes to greater oral health with decreased caries and tooth loss [14, 15]. Conversely, poor oral health can impact self-esteem, confidence, and the perceived ability to obtain future employment [12, 16]—characteristics reflected by PSS.

Traditionally, oral health research has focused on measures of SES as predictors of health-promoting behaviors. Only one study has examined associations between PSS and oral health-promoting behaviors [17]. Kino et al. demonstrated a positive association between PSS and odds of dental utilization among adults in 27 European countries. However, no research has examined the association between PSS and dental utilization in a United States, publicly insured population. Thus, the aim of this study was to (1) explore the association between PSS and self-reported dental utilization, and (2) assess the relative effects of PSS and measures of SES on dental utilization.

This study tested the hypotheses that PSS is associated with self-reported preventive dental utilization in Medicaid-enrolled adults (hypothesis 1), and that this relationship would remain significant after controlling for factors associated with dental utilization (hypothesis 2). We hypothesized that three objective SES measures—educational attainment, employment status, and income would be associated with preventive dental utilization (hypothesis 3). We also hypothesized that PSS would have greater strength of association with preventive dental utilization than three objective SES measures—educational attainment, employment status, and income (hypothesis 4).

METHODS

Iowa's Medicaid program has a unique structure. It provides comprehensive dental benefits to low-income adults aged 19–64 with incomes up to 138% federal poverty level (FPL). However, members must complete healthy behaviors requirements annually to maintain full benefits. These healthy behaviors include a preventive dental visit and an oral health self-risk assessment. If unable to complete these requirements, dental benefits are reduced to limited services only unless members pay a $3 monthly premium [18]. Two dental carriers, Delta Dental of Iowa and MCNA Dental, provide dental benefits for Medicaid enrollees. Both carriers are required to offer the same benefits; however, each carrier has a separate network of dental providers [18].

Data and sample

This data source for this study was a 2018 mixed-mode survey of enrollees in Iowa's Medicaid program. Paper surveys were mailed in March–April 2018, to a random sample of 19- to 64-year-old enrollees (N = 18,000). The sampling frame for the survey included members who had been enrolled for at least 6 months, and those enrolled through either Iowa's Medicaid expansion or traditional, fee-for-service Medicaid. The sample frame excluded pregnant enrollees as they are exempt from premium obligations and do not face reduced dental benefits associated with failure to complete programmatic requirements, and only one person per household could be selected. Based on Medicaid eligibility requirements, all individuals had incomes at 0%–138% of the FPL. As an incentive, all recipients received a $2 bill in the first survey mailing. Additional details regarding survey development have been previously published [18].

Survey topics included enrollees' experiences with their dental plan, use of dental services in the previous year, barriers to receipt of dental care, self-rated oral health, PSS, and demographics. Survey items included original items and items adapted from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Dental Plan Survey [19].

This project received a determination of “not human subjects research” under a waiver approved by the Secretary, US Department of Health and Human Services, for Section 1115 projects conducted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. At the time, the Iowa Dental Wellness Plan had federal approval through this Section 1115 waiver.

Variables

The dependent variable was a dichotomous indicator of having at least one self-reported preventive dental visit in the previous year. Dental utilization was assessed with the following survey question: “Since July 2017 [the beginning of the program], have you seen a dentist for a checkup or cleaning?” Response options were ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Independent variables of interest

Perceived Social Status

Perceived social status (PSS) was assessed using a modified version of the MacArthur ladder [20]. Respondents were asked: “Please think of how you see yourself compared to other people in society. One a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 are people who are the worst off and 10 are people who are the best off, where would you place yourself?” The survey item was modified from the original MacArthur item to be consistent with the format of this survey in the following ways: the ladder graphic was removed, we used the term ‘scale’ versus ‘ladder,’ and respondents were asked to check a box corresponding to their score (rather than marking an ‘x’ on a ladder rung). A score of 1 included the description ‘Worst off: least education, least money, worst jobs or no jobs;’ ‘10 indicated the top of the scale and included the description Best off: most education, most money, best jobs.’

Measures of SES

Three measures of SES were compared against PSS in their association with dental utilization: educational attainment, employment status, and income. Income was derived from Medicaid enrollment data and ranged from 0% to 138% of the FPL, corresponding to eligibility requirements. The variable was dichotomized into two categories, 0% and >0% FPL because nearly 85% of survey respondents had incomes of 0% FPL.

Control variables

Multivariable analyses also controlled for predisposing, enabling, and need-related variables as identified by Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use [21]. Frequently used in healthcare use research, the Behavioral Model provides a framework for understanding factors associated with healthcare utilization and interpretation of results [22]. Covariate selection was based on documented associations with dental utilization [21-23].

Predisposing variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and residential rurality. Rurality was determined using residential postal code (ZIP) and categorized using Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes as ‘Urban,’ ‘Large rural,’ and ‘Small rural’ [24]. Enabling variables included having a regular dentist, ability to obtain transportation to a dental appointment, concern with the cost of transportation to a dental appointment, health literacy, and knowledge of dental benefits, and perceived dental need. A proxy for health literacy was measured using a question that ask respondents how often they required help to read medical material with response options ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always.’ Knowledge of dental benefits was measured by two survey items: whether an individual knew that their Medicaid benefits included dental coverage, and whether they knew which of the two Iowa dental carriers provided their coverage. Perceived dental need was measured using self-reported oral health, oral pain, and perceived need for dental care.

Analyses

Bivariate and logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate relationships between potential associated variables and dental services use. Bivariate analyses to compare predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of respondents by preventive dental utilization were performed using chi-square tests and t-tests. A significance level of 0.1 was used to select covariates for multivariable regression analysis. Nonresponse error analyses were completed using bivariate comparisons between respondents and nonrespondents using program eligibility data.

Multivariable regression models were used to examine the association between self-reported preventive dental utilization, PSS, and SES measures while adjusting for control variables. We constructed three logistic regression models. Model 1 included PSS as the primary independent variable. Model 2 included educational attainment, employment status, and income entered simultaneously to evaluate the relationship between objective SES measures and dental utilization. Model 3 included PSS, SES measures, and control variables, entered simultaneously to evaluate whether PSS would remain significant. Model were compared using −2 log-likelihood (−2LL) values. Hosmer-Lemeshow test of goodness of fit was used to test model significance. Multicollinearity in the models was evaluated using tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All analyses were completed using SPSS Version 27 (Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The adjusted sample size was 15,779 after excluding undeliverables, and the adjusted response rate was 25% (n = 3977). The final study sample was 2252 after excluding surveys that did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e., enrolled in Medicaid due to disability, not income status) (n = 1727) and those with missing data (n = 231). Nonresponse error analyses found that respondents were significantly more likely to be female (66% vs. 62%, respectively; p < 0.05), older (mean age 44 versus 39 years, respectively; p < 0.05), and white (70% versus 64%, respectively; p < 0.05) when compared to nonrespondents.

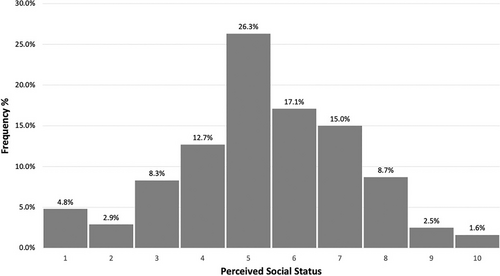

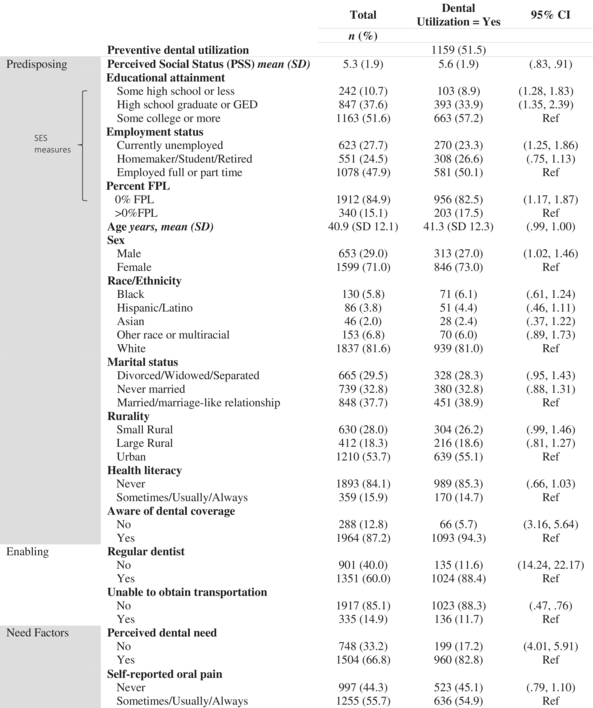

The distribution for PSS is presented in Figure 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1. Mean PSS was 5.3 (SD 1.9, range 1–10). Among the three SES measures, 56% of survey respondents had at least some college education, 48% were intentionally unemployed (homemaker, student, or retired), and 85% had incomes of 0% FPL. The median PSS score for both utilizers and non-utilizers was 5.0. While median values of PSS were equal between those who utilized services and those who did not, the interquartile ranges for PSS scores varied significantly among utilizers (IQR: 5–7) and non-utilizers (IQR 4–6).

|

Dental utilization and bivariate analysis results

Chi-square tests revealed that a significantly higher proportion of adults who utilized preventive dental services had some college education (47%) compared to high school graduates (24%) (p < 0.0001) and adults with less than or some high school education (8.9%) (Table 1). A significantly greater proportion of utilizers had incomes of 0% FPL (85%) compared to individuals without a dental visit. Additionally, preventive dental utilization was higher among employed Medicaid adults (50%) compared to unemployed adults (23%).

Perceived social status and dental utilization multivariable logistic regression results

Results of the multivariable logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 2, presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence levels. We examined whether PSS was associated with preventive dental utilization, while controlling for covariates in model 1. Model 1 excluded the three SES items (education, employment, and income) to examine whether PSS was associated with dental utilization (Hypothesis 2). Results show that PSS was significantly associated with preventive dental utilization; the odds of utilizing services increased 13% per unit of PSS (OR = 1.13, CI = 1.07, 1.20, p < 0.001). Model 2 included SES measures and covariates without PSS to determine whether measures of SES were associated with preventive dental utilization (Hypothesis 3).When entered together in the regression analysis in model 2, none of the SES items were significantly associated with dental utilization.

| PSS | SES | PSS and SES | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3b | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| PSS | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20)*** | Not included | 1.11 (1.05, 1.18)*** |

| SES | Not included | ||

| Education | |||

| ≤Some high school | 0.77 (0.53, 1.12) | 0.81 (0.55, 1.19) | |

| High school degree | 0.87 (0.69, 1.11) | 0.91 (0.72, 1.12) | |

| ≥Some college | Ref | Ref | |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 0.78 (0.60, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14) | |

| Homemaker/student/retired | 1.10 (0.83, 1.45) | 1.12 (0.84, 1.48) | |

| Employed full or part time | Ref | Ref | |

| Income | |||

| 0% FPL | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | 0.83 (0.60, 1.14) | |

| >0% FPL | Ref | Ref | |

| −2 loglikelihood | 2023.44 | 2029.63 | 2017.44 |

- Note: Dependent variable: self-reported preventive dental utilization (i.e., checkup or cleaning) (0 = no, 1 = yes).

- Abbreviations: PSS, perceived social status; SES, socioeconomic status.

- a Models adjusted for: age, sex, health literacy, coverage awareness, regular dentist, ability to obtain transportation, and perceived need of dental care.

- b Full model adjusted for: age, sex, health literacy, coverage awareness, regular dentist, ability to obtain transportation, and perceived need of dental care.

- *** p < 0.001.

In the full model (model 3), PSS remained significant when controlling for covariates and measures of SES (Hypothesis 4). However, the association between PSS and dental utilization was approximately the same with the inclusion of SES items (OR = 1.11; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.18). The −2LL values for model 1 (2023.44), model 2 (2029.63), and model 3 (2017.44) demonstrated that there was a decrease in the −2LL, indicating that the full model (model 3) was a statistically significantly better fit for the data.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between PSS and self-reported preventive dental utilization among a low-income adult population in the state of Iowa and to compare the strength of association between dental utilization and both PSS and SES measures. Results demonstrated that PSS, a measure of where individuals identify themselves on the social hierarchy relative to their peers, was associated with preventive dental utilization. This is consistent with our first hypothesis that higher PSS would be positively associated with preventive dental utilization and remained significant when controlling for factors associated with dental utilization; our second hypothesis. One potential mechanism of action by which PSS is related to preventive dental care use is via psychological factors, such as sense of control or self-esteem, which may support oral health-promoting behaviors, such as preventive dental utilization. Unfortunately, we were unable to evaluate perceived sense of control as it was not explicitly asked on the 2018 survey. However, it will be an item of exploration in future analyses regarding PSS and dental utilization.

Interestingly, contrary to our third hypothesis, the three SES variables were not associated with preventive dental utilization within this study. While this supports our fourth hypothesis, the lack of association between measures of SES and dental utilization deviates from the literature, where SES has been associated with dental utilization [23]—even when adjusting for control variables [21]. This may be due to the fairly homogenous nature of our study population. Since our study sampled Medicaid-enrolled individuals, they may face additional barriers to obtaining dental care that outweigh the objective SES measures, such as ability to find a dentist who accepts Medicaid and having a regular dentist.

PSS, however, remained significant in the full model that included SES measures and control variables. This supported our fourth hypothesis that PSS would demonstrate a greater association compared to objective SES measures. This supports the idea that PSS may capture aspects of social class that objective measures are not able to account for. Previous literature has demonstrated social gradients within homogeneous social classes and demonstrated that PSS was able to better predict health outcomes than objective SES measures [25].

This is the first study of its kind to evaluate the association of PSS with preventive dental utilization in the United States, Medicaid population. Results of this study suggest that there is a higher prevalence of preventive dental utilization among individuals who rate themselves as having higher PSS compared to those who rated PSS lower. Although one previous study focused on the relationship between PSS and dental utilization in among several countries [17], the narrower focus of this study in a more homogenous population allows for a more focused examination of the relationship between PSS and dental utilization. Thus, allowing for a better understanding PSS and facilitators of preventive dental utilization. Additionally, our study did not find an association between objective SES items and dental utilization, despite documented associations in previous studies [23]. This divergence may indicate that additional influences may be at work—particularly in a publicly insured low-income adult population that may experience external barriers to dental care. Underscoring the importance of one's perception of their own social class more so than objectives measures of social class in their care-seeking behavior.

Manski and Magder asserted that although traditional measures of SES affect dental utilization, other systematic racial/ethnic differences, cultural barriers, and/or personal motivators must be important because the traditional determinants do not fully explain utilization patterns for all [26]. Individuals with higher PSS may be able to overcome barriers to care more easily. PSS may provide a more comprehensive understanding of these other factors that influence utilization of dental services.

The primary limitation to this study was the cross-sectional design and therefore results cannot be used to infer causality. Nonresponse error can be a limitation to this study. Nonresponse analyses found that respondents were more likely to be female, older, and white compared to nonrespondents. As sex was related to self-reported dental utilization in this study, self-reported dental utilization among participants may be higher than among the full Medicaid population. The low response rate can also be considered a limitation; however, low response rates are common in mailed surveys of Medicaid members—typically in the 20%–30% range [27], and low response rates may not indicate of response bias [28]. This study was conducted in a single U.S. state and may not be generalizable to other low-income populations in other states. Additionally, a majority of the study sample were White (82%). Associations between PSS and preventive dental utilization may differ across racial and ethnic groups, as PSS varies among racial groups [3]. Moreover, nearly 85% of the study population was at 0% FPL. With a large portion of the study population not earning an income, they may face additional barriers to those at >100% FPL and with potential income to put towards direct and indirect costs associated with preventive dental utilization.

Despite these limitations, results of this study may shed light on factors that enable individuals to perform oral health-promoting behaviors. Although 85% of respondents were at 0% FPL, PSS was normally distribution among the study population. This result alone could suggest the need for PSS when evaluation social status in health research. Results of any study may vary significantly depending on the social status item used. For example, no association was found between percent FPL and preventive dental utilization in this study. Using percent FPL may not be appropriate proxy for social status in this population as objective SES measures do not account for the perceived feeling an individual has of their position within society and resources available to them. PSS takes this perception into account and is a valid and reliable indicator of cumulative socioeconomic circumstances and control over one's situations [2, 5]. Thus, PSS may act as an additional source of stress or—conversely—as in this study, a contributor to utilizing preventive dental services. Research has shown that lower perceived control [29] and self-esteem [30] decreases PSS, and thus in turn may impact the association of PSS and oral health promoting behaviors.

The addition of PSS to health services research provides an important contribution to our understanding of the relationship between socioeconomic position and utilization of health services. Therefore, PSS may be influenced by perceived control in one's life situations and thus may also contribute to one's perceived control to perform oral health promoting behaviors. One application might be using this simple survey item to assess how much support someone might need to get dental care and be able to obtain routine dental care. Using the PSS item on patient intake forms or as part of health history documentation, may help give the dental provider an idea as to an individuals' resources and ability to utilize dental services on a routine basis. Results of this study suggest that PSS is a unique concept that may broaden the definition, measurement, and understanding of social status in oral health research and targeting interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31DE030363. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was part of a program evaluation funded by the Iowa Department of Human Services (DHS). The Iowa DHS was not involved in the development, analysis, writing or review of this manuscript.