European S2k guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa part 2: Treatment

Abstract

Introduction

This second part of the S2k guidelines is an update of the 2015 S1 European guidelines.

Objective

These guidelines aim to provide an accepted decision aid for the selection, implementation and assessment of appropriate and sufficient therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa (HS).

Methods

The chapters have been selected after a Delphi procedure among the experts/authors. Certain passages have been adopted without changes from the previous version. Potential treatment complications are not included, being beyond the scope of these guidelines.

Results

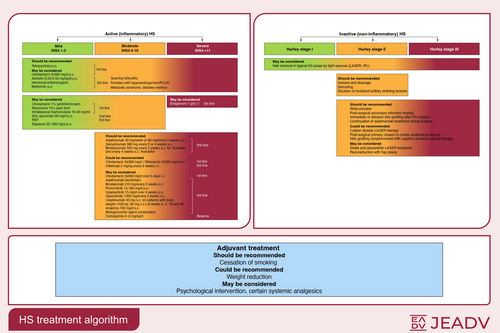

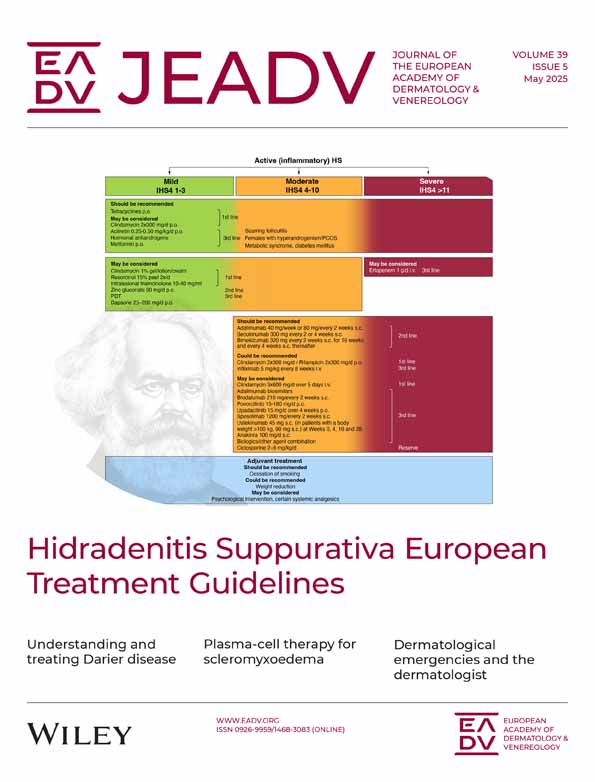

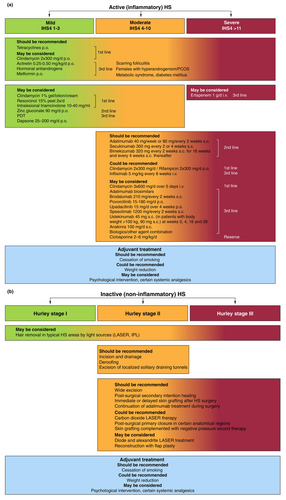

Since the S1 guidelines publication, validation of new therapeutic approaches has almost completely overhauled the knowledge in the field of HS treatment. Inflammatory nodules/abscesses/draining tunnels are the primary lesions, which enable the classification of the disease severity by new validated tools. In relation to the degree of detectable inflammation, HS is classified into the inflammatory and the predominantly non-inflammatory forms. While the intensity of the inflammatory form can be subdivided by the IHS4 classification in mild, moderate and severe HS and is treated by medication accordingly, the decision on surgical treatment of the predominantly non-inflammatory form is based on the Hurley stage of the affected localization. The effectiveness of oral tetracyclines as an alternative to the oral combination of clindamycin/rifampicin should be noted. The duration of systemic antibiotic therapy can be shortened by a 5-day intravenous clindamycin treatment. Adalimumab, secukinumab and bimekizumab subcutaneous administration has been approved by the EMA for the treatment of moderate-to-severe HS. Various surgical procedures are available for the predominantly non-inflammatory form of the disease. The combination of a medical therapy to reduce inflammation with a surgical procedure to remove irreversible tissue damage is currently considered a holistic therapeutic approach.

Conclusions

Suitable therapeutic options while considering HS severity in the therapeutic algorithm according to standardized criteria are aimed at ensuring a proper therapy.

Graphical Abstract

Why was the study undertaken?

- Since the S1 guidelines publication in 2015, validation of new therapeutic approaches has almost completely overhauled the knowledge in the field of hidradenitis suppurativa treatment.

What does this study add?

- New hidradenitis suppurativa classification: inflammatory form (mild, moderate and severe; IHS4 classification) and predominantly non-inflammatory form (Hurley staging). Algorithm of predominantly medical (oral tetracyclines vs. clindamycin/rifampicin, short-term intravenous clindamycin, EMA-approved biologics: adalimumab, secukinumab and bimekizumab) and surgical treatment (various procedures), respectively.

What are the implications of this study for disease understanding and/or clinical care?

- A therapeutic algorithm with suitable therapeutic options while considering HS severity according to standardized criteria ensure a proper therapy. The combination of medical therapy reducing inflammation with surgery to remove irreversible tissue damage is considered a holistic therapeutic approach.

OBJECTIVES OF THE GUIDELINES

The present second part of the S2k guidelines is an update of the latest edition of the S1 European guidelines from 2015 and their algorithm.1, 2 The first part is parallelly published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.3 The chapters have been selected after a Delphi procedure among the experts/authors. Certain passages have been adopted without changes from the previous version. The general aim of these guidelines is to provide dermatologists in offices and clinics as well as physicians of other specialties with an accepted decision aid for the selection and implementation of appropriate and sufficient therapy of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa (HS). No comprehensive list of potential treatment complications is included, since this would be beyond the scope of these guidelines.

Improvement of the care of patients by implementation of guideline recommendations and optimization of the knowledge of physicians with respect to effectiveness proven in studies

Personal experience and traditional therapeutic concepts of physicians concerning the efficacy of individual therapies of HS shall be complemented and, if necessary, replaced by the consented recommendations.

Aid for stage-related implementation of therapies according to the predominant severity

Especially, the presentation of suitable therapeutic options while considering the severity of HS in the therapeutic algorithm is aimed at ensuring a correct therapy.

Reduction in severe disease courses and scar formation

The comprehensive presentation of systemic therapies with detailed description of their use has the aim to overcome reservations concerning these therapeutic procedures among physicians and patients and to ensure their timely, sufficient and optimal implementation. The timely initiation of sufficient therapies is aimed at reducing severe disease courses that are often accompanied by pronounced scarring. This includes the development of therapeutic objectives and targets used to monitor treatment success and to change the therapy, if necessary.

Promotion of compliance

Compliance is often associated with a ratio of benefit to effort, costs and adverse effects acceptable for the patient. The individual selection of particularly effective therapies, taking also the parameters on quality of life assessed in new studies into account, has the aim to ensure an especially high therapeutic benefit for the patients. Information about treatment and avoidance of adverse effects is aimed at avoiding or reducing these effects, thus further promoting compliance.

OBJECTIVES OF HS TREATMENT

Regular control and, if necessary, adjustment of the therapy with respect to potentially changing disease severity are advisable. This is also required to ensure compliance (timely modification of therapy in patients responding inadequately to therapy or in case of adverse drug reactions). The assessment should be performed according to standardized criteria4 taking the objectifiable lesions into account and after recording the disease-related impairment of the quality of life of the patient. If no significant reduction in the inflammatory activity of the lesions or no improvement of the quality of life is observed after 12 weeks, the therapy should be modified while taking the partly different rates of effectiveness into account. The recommended indicators for assessment are depicted in the first part of the guidelines under ‘Severity classification and assessment’.

What's new?

Since the publication of the S1 guidelines in 2015,1 validation of new therapeutic approaches has almost completely overhauled the knowledge in the field of HS treatment. Inflammatory nodules and abscesses (AN), and draining tunnels are the primary lesions of the disease, which enable the calculation of the disease severity by new validated classification tools, especially the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Scoring System (IHS4).4 HS is classified into two forms in relation to the degree of detectable inflammation: the inflammatory and the predominantly non-inflammatory form.5, 6 While the intensity of the inflammatory form can be subdivided by means of the IHS4 classification in mild, moderate and severe HS and is treated by medication accordingly, the decision on surgical treatment of the predominantly non-inflammatory form is based on the Hurley stage of the affected localizations, that is Hurley stage I, II and III.5, 7 Concerning the field of classical drug therapy, the effectiveness of systemic oral tetracyclines, which is similar to the effectiveness of oral systemic combination of clindamycin and rifampicin, should be noted.8 In addition, it may be possible to shorten the total duration of systemic antibiotic therapy to a 5-day systemic intravenous (i.v.) therapy of clindamycin.9 On the contrary, the number of clinical trials with biologics is constantly increasing. Adalimumab,10 secukinumab11 and bimekizumab12 have been approved as subcutaneous (s.c.) injections for the therapy of HS. Various surgical procedures are available for the predominantly non-inflammatory form of the disease. The combination of a medical therapy to reduce inflammation with a surgical procedure to remove irreversible tissue damage is currently considered a holistic therapeutic approach in HS.13

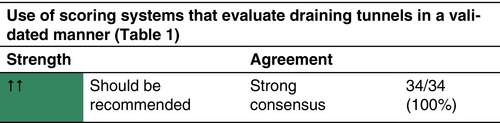

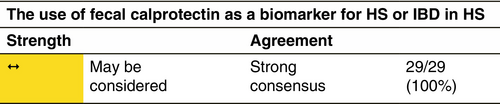

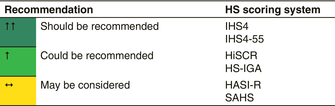

SCORING SYSTEMS FOR HS CLINICAL TRIALS

For a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory disease like HS, it is important to have a scoring system that is well validated and can serve as primary outcome for clinical trials. Important key points for such a score are validation against other physician and patient-reported outcomes, ability to be used both in clinical trials and daily clinical practice, validation in different datasets, be dynamic, consensus-based and provide an acceptable intra- and interobserver variability (Table 1).14

Hidradenitis suppurativa clinical response (HiSCR)

The HiSCR was developed retrospectively from a phase 2 randomized controlled trial involving adalimumab treatment, which used other outcome measures in the trial itself.15 The HiSCR identifies responders as those who achieve at least a 50% reduction in AN count without an increase in the number of abscesses or draining tunnels relative to baseline. Later on, in the pooling dataset of phase 3 adalimumab trails, HiSCR has been validated and it has been shown that irrespective of treatment, significantly more HiSCR responders than non-responders experienced clinically meaningful improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Pain Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Hidradenitis Suppurativa Quality of Life (HS-QoL), work-related performance and non-work-related performance.16

Although it has been adopted as Federal Drug Administration (FDA)-supported primary endpoint in almost all randomized controlled trials (RCT) subsequently, the drawbacks of HiSCR have become increasingly apparent in recent clinical trials. Firstly, patients with an AN count <3 were excluded from the clinical trial in which the HiSCR was developed. This means that HiSCR may be less stable in patients with an AN count <3 and it is, therefore generally not used in such patients. Consequently, these patients are excluded from participating in all clinical trials that use HiSCR as the primary endpoint. Secondly, the HiSCR does not dynamically take into account draining tunnels.

During recent clinical trials, other drawbacks of the HiSCR were identified. In particular, the SHINE study, a phase 2 RCT assessing the efficacy of vilobelumab/IFX-1 in patients with moderate-to-severe HS compared with placebo was instrumental in bringing these drawbacks to light.17 In this trial, the HiSCR rate was not statistically different between active treatment and placebo group, even though patients in the highest dosed treatment group achieved a significantly greater reduction in AN count and draining tunnels relative to the placebo group at Week 16. This highlights the drawback that HiSCR, by not dynamically incorporating draining tunnels, cannot fully capture the effect of anti-inflammatory treatment.

IHS4 and IHS4-55

IHS4 is a validated tool to dynamically assess HS severity and can be used both in real-life and in the clinical trials setting. IHS4 is calculated by the number of nodules (multiplied by 1) plus the number of abscesses (multiplied by 2) plus the number of draining tunnels (multiplied by 4). A total score of ≤3 or less signifies mild, 4–10 signifies moderate and ≥11 signifies severe disease. It correlates well with Hurley classification, Expert Opinion, Physician's Global Assessment, Modified Sartorius score and DLQI.4 It has been used as an entry criterion for inclusion in clinical trials and has been suggested as a paediatric clinical trial inclusion criterion.18 Inter-rater and intra-rater agreement was found to be good and intra-rater reliability was very good.19, 20 The continuous IHS4 score has been adopted as a secondary outcome measure, in addition to the HiSCR, in many recently completed, ongoing and upcoming clinical trials. However, the preference of the FDA for a dichotomous outcome has resulted in the continuous IHS4 not being implemented as a primary outcome even after the drawbacks of the HiSCR have been highlighted.

Therefore, IHS4-55,21 a dichotomous version of the IHS4, has been developed and validated both in phase 3 clinical trials setting for biologic agents and in datasets with patients treated with antibiotics.8 The optimal cut-off threshold was identified as a 55% reduction in total IHS4 score. The performance of the IHS4-55 was presented to be similar to that of HiSCR in the PIONEER datasets while addressing the main drawbacks of the HiSCR.21 The dichotomous IHS4 takes draining tunnels into account in a dynamic and validated manner, and it does not exclude patients with an AN count <3 but many draining tunnels. The best performing cut-off for the IHS4 was a 55% reduction in the IHS4 score (IHS4-55). Patients who achieved the IHS4-55 had an odd's ratio of 2.00 (95%-CI 1.26–3.18, p = 0.003), 2.79 (95%-CI 1.76–4.43, p < 0.001) and 2.16 (95%-CI 1.43–3.29, p < 0.001) for being treated with adalimumab rather than placebo in PIONEER-I, PIONEER-II and the combined dataset, respectively. Additionally, achievement of the IHS4-55 was associated with a significant reduction in inflammatory AN and draining tunnels in all analysed datasets.

Moreover, the external validation of the dichotomous IHS4 in a large Europe-wide prospective antibiotics study showed that the score was not only responsive in patients treated with adalimumab but also in patients treated with secukinumab and antibiotics.8, 22 Achievers of the IHS4-55 demonstrated a significant reduction in the count of inflammatory AN and draining tunnels (all p < 0.001). Additionally, IHS4-55 achievers had an odds ratio (OR) for achieving the minimal clinically important change (MCIC) of DLQI, NRS pain and NRS pruritus of 2.16 (95% CI 1.28–3.65, p < 0.01), 1.79 (95% CI 1.10–2.91, p < 0.05) and 1.95 (95% CI 1.18–3.22, p < 0.01), respectively.

This evidence suggests that IHS4-55 is a well-validated outcome that can be used as a novel primary outcome for clinical trials and daily clinical practice and that IHS4-55 addresses some of the HiSCR drawbacks dynamically, by including draining tunnels in a validated manner. By allowing the analysis of patients with an AN count <3 but many draining tunnels, this outcome measure will improve inclusivity in clinical trials.

Severity Assessment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa (SAHS)

SAHS is a severity score, including number of involved regions (axillas, submammary areas, intermammary or chest, abdominal, mons pubis, groins, genital, perianal or perineal, gluteal regions and others [e.g. neck and retroauricular]), number of inflammatory and/or painful lesions other than tunnels and number of tunnels. It has been validated only in correlation with modified Sartorius and Hurley score and has been found well correlating with them.23 Responsiveness to treatment has been tested in a prospective manner in a case series of treated patients from a single centre. A dichotomous outcome has not been developed yet. The validation in clinical trial settings and other datasets is also lacking.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa area and severity index revised (HASI-R)

HASI-R measures inflammatory colour change, inflammatory induration, open skin surface and extent of tunnels, in various body sites using an estimation of involved body surface area (BSA).24 Each of these variables is scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0 = none; 1 = limited/mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe/extensive) based on the average intensity for each body site.

It has been shown that it has moderate inter-rater reliability and excellent intra-rater reliability.24 Divergent validity, assessed by correlation with the reverse-scored DLQI, showed a weak, non-significant correlation. It has no established and validated cut-off points for severity group and has not been validated according to patient-reported outcomes. A dichotomous outcome has not been established and the validation in clinical trial settings and other datasets is lacking. It remains unknown how the HASI-R performs in a diverse patient population and how responsive this score is to change after anti-inflammatory therapy.

HS-investigator global assessment (IGA)

The HISTORIC effort developed and provided initial validation for HS-IGA, an investigator global assessment HS-specific tool.25 Regardless of lesion type, axillary and inguinal regions most influenced the HS-IGA score. The score was well correlated with HS-physician global assessment (PGA) and HiSCR along with DLQI, NDS pain and HS-QoL .

|

OVERVIEW OF THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

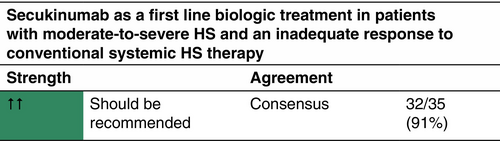

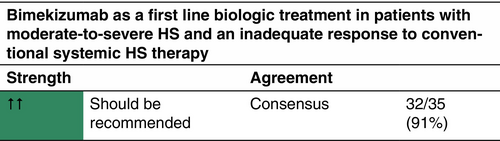

Currently, the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitor adalimumab, the interleukin (IL)-17A inhibitor secukinumab and the IL-17A/F inhibitor bimekizumab are the only European Medicines Agency (EMA)-approved compounds for the medical treatment of HS.26 Adalimumab is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe active HS in patients aged 12 years and older with inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy.10, 27 Secukinumab11 and bimekizumab12 are approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe active HS and inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy. All other therapeutic options discussed in this guideline—except for monotherapy with antibiotics—should be considered off label.

ADJUVANT THERAPY

General measures

General adjuvant measures in HS include weight loss, smoking cessation, physical exercise, healthy lifestyle, pain control (detailed information is provided in the section ‘Lifestyle interventions, analgesics and wound care’).

Local antiseptics

There is no scientific evidence to recommend the use of over-the-counter skin cleansers with antibacterial or anti-inflammatory properties such as chlorhexidine, benzoyl peroxide, zinc pyrithione, triclosan.1, 28-32

Menstrual products and deodorants

There is insufficient evidence to make recommendations for or against the use of specific menstrual products, deodorants and antiperspirants.33-35

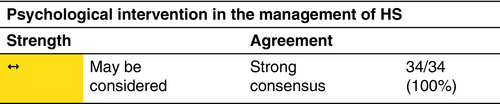

Psychosocial support measures

TOPICAL THERAPY – NONANTIBIOTICS

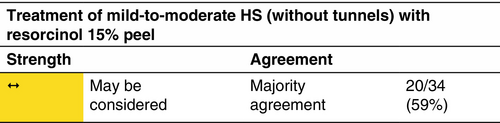

Resorcinol

Topical resorcinol 15% has been shown to be effective and well tolerated in reducing the size and number of non-fistulous HS lesions and decreasing pain and lesion duration.37-40

Mechanism

Resorcinol (m-dihydroxy benzene) is a phenolic compound with keratolytic, antipruritic and antiseptic activities. It is administered in an oil/water cream with emulsifying waxes; ingredients listed as cremor lanette, consisting of the following components: alcohol cetylicus et stearylicus emulsificans b (cetostearyl alcohol type b), acidum sorbicum (sorbates), cetiol V (decyloleat), sorbitolum liquidum cristallisabile (sorbitol) and aqua purificata (water). In Europe, it is not marketed in 15% concentration and has to be prepared as a compound.39 The formulation package in aluminium tubes has shown the physicochemical and microbiological stability of resorcinol for 12 months at room temperature.41

Indication

Mild-to-moderate HS (according to the IHS4 classification) without draining tunnels/localized Hurley stage I and mild stage II. No formal studies or guidelines are available on the use of resorcinol in pregnancy.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Resorcinol 15% twice daily in a flare and once daily as a maintenance treatment for up to 16 weeks.

Response rate

Other therapies

In a case series, including 11 HS patients, azelaic acid was not effective in improving DLQI and NRS.43

TOPICAL ANTIBIOTICS

Clindamycin

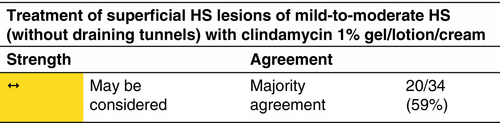

Clindamycin is the only antibiotic that has been studied as a topical agent.44, 45

Mechanism

Clindamycin binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit of bacteria, where it disrupts transpeptidation and subsequently protein synthesis in a similar manner to macrolides although not chemically related.

Indication

Mild-to-moderate HS (according to the IHS4 classification) without draining tunnels.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Clindamycin 1% gel/lotion/cream twice daily in a flare for up to 12 weeks. Treatment may be prolonged if clinically indicated.

Results

SYSTEMIC ANTIBIOTICS

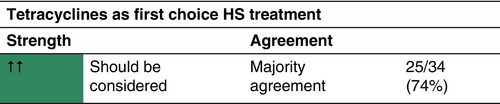

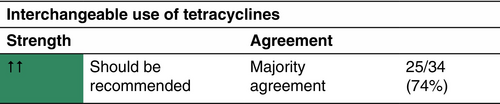

Tetracyclines

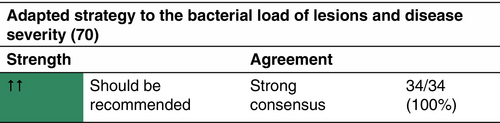

The largest study on the efficacy of tetracyclines to date is a prospective, multicentre cohort study comparing oral tetracyclines with oral clindamycin and rifampicin.46 Out of the included 283 patients, 103 received oral tetracyclines (tetracycline, n = 42; doxycycline, n = 121; minocycline, n = 17).

Mechanism

Tetracyclines bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit reversibly and prevent the binding of the amino acyl tRNA and thus translation.

Indication

Tetracyclines can be prescribed to mild-to-severe HS patients (according to the IHS4 classification).46, 47 They should not be administered to pregnant women or children younger than 9 years old due to risk of discoloration of permanent teeth.48

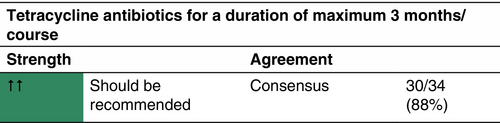

Dosage and duration of treatment

All tetracycline antibiotics are administered for a duration of 3 months.

Response rate

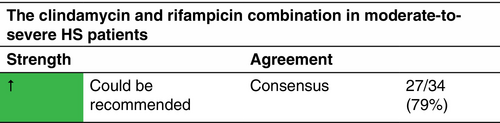

Clindamycin and rifampicin

Multiple studies have deemed combination treatment with clindamycin and rifampicin to be beneficial in HS.50-52 However, the aforementioned prospective study by van Straalen et al.46 demonstrated that clindamycin in combination with rifampicin shows similar efficacy as tetracyclines regardless of disease severity.

Mechanism

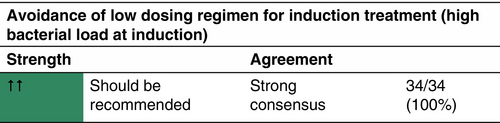

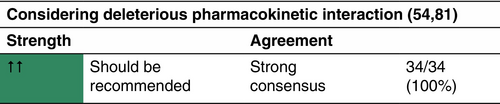

For clindamycin see chapter ‘Topical antibiotics – Clindamycin’. Rifampicin inhibits DNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity in bacteria, by interacting with bacterial RNA polymerase. Moreover, it significantly inhibits IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and TNF-α production in ex vivo HS lesional skin explants.53 Rifampicin is a strong inducer of cytochrome P450 and may influence the metabolism and toxicity of other drugs metabolized by the same pathway, such as oral contraceptives. Combined treatment with rifampicin and clindamycin has been shown to significantly reduce the plasma concentration of clindamycin in patients with HS.54 However, the clinical importance of this finding remains unknown.

Indication

Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin p.o. may be considered for individual moderate-to-severe HS patients (according to the IHS4 classification).

Dosage and duration

In combination treatment, clindamycin and rifampicin are administered in a dosage of 2 × 300 mg/day p.o. each for the duration of 10–12 weeks.

Response rate

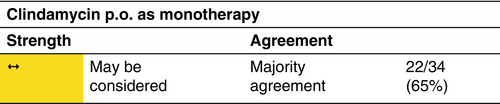

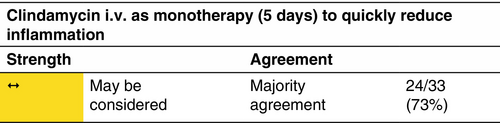

Clindamycin

Clindamycin monotherapy—p.o. or i.v.—may be considered instead of the combination of clindamycin and rifampicin.

Mechanism

See chapter ‘Topical antibiotics – Clindamycin’.

Indication

Clindamycin p.o. monotherapy has been assessed in mild-to-severe HS patients and shows a significantly better response rate in mild-to-moderate patients (IHS4).55, 56 Clindamycin i.v. has been studied as a first choice treatment in therapy-naïve patients with moderate-to-severe HS.9

Dosage and duration of treatment

Clindamycin monotherapy has been assessed for the dosage of 2 × 300 mg/day p.o. for the duration of 12 weeks as well as 3 × 600 mg/day i.v. over 5 days.

Response rate

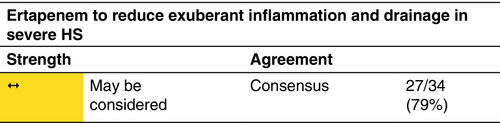

Ertapenem

Mechanism

Ertapenem is a broad-spectrum i.v. β-lactam antibiotic belonging to a group of antibiotics known as carbapenems. It covers aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Ertapenem is bactericidal as it binds to the penicillin-binding proteins that weaken or interfere with cell wall formation.

Indication

Ertapenem may be considered in severe HS patients (according to the IHS4 classification) and for down-staging prior to surgery.

Dosage and duration of treatment

One gram per day i.v. infusion as a 6-week course.

Response rate

Other antibiotics

A range of other systemic antibiotics have been suggested in case reports and in expert opinion, but none have been systematically evaluated even at the level of open prospective case series. The treatments mentioned below should currently be considered as experimental therapies.

Clindamycin and ofloxacin

The combination of clindamycin with ofloxacin has been retrospectively assessed among 65 patients with mild-to-moderate HS for a mean duration of 4.3 months (range, 1–20).59 Four different dosages were used for clindamycin (600–1800 mg), and two different dosages for ofloxacin (200 or 400 mg) based on the patients' weight. Thirty-eight patients (58%) reported improvement of disease activity, with complete response for 22/65 (34%) and partial remission in 16/65 (25%). Clinical worsening was reported by seven (11%) patients and early cessation of treatment by 11 patients (17%). Twenty-eight per cent (18/65) of the patients reported side effects.

Rifampicin-moxifloxacin-metronidazole

Systemic treatment with a combination of rifampicin-moxifloxacin-metronidazole, either alone or preceded by systemic ceftriaxone in half of the patients, has been described as effective in an retrospective study of 28 patients with treatment-resistant moderate-to-severe disease.60 Patients who showed response after 12 weeks of initial treatment were treated for an additional 12 weeks using a combination of moxifloxacin and rifampicin. The treatment led to complete response in 16/28 patients (57%). Main adverse effects were gastrointestinal symptoms and vulvovaginal candidiasis.

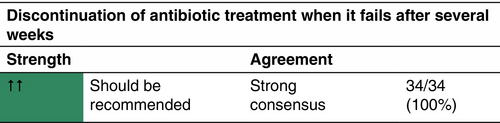

CONSIDERATION OF BACTERIAL RESISTANCE UNDER LONG-TERM ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT

Long-term antibiotic treatment can lead to antibiotic resistance. This may pose a problem as international HS guidelines typically recommend antibiotic treatment for 10–12 weeks as first-line therapy in patients with mild-to-moderate disease severity and antibiotics are also intermittently used to control flares.1, 2, 7, 61-67 Antibiotic treatment in HS is used with alleged anti-inflammatory properties,50-52, 68 but an antimicrobial effect cannot be ruled out, given the presence of a rich bacterial flora within lesions.69-72 Whichever mechanism is related to efficacy, any antibiotic may induce resistance in patient's microbiome. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control consider the rising antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as a major public health concern.73 Data on AMR in HS patients treated with antibiotic are scarce, and only a few evaluated AMR development after an antibiotic course in HS patients.56, 74

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY TREATMENT

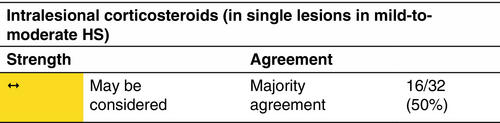

Intralesional corticosteroids

Indication

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide showed effectiveness in rapidly reducing inflammation associated with acute flares and in managing recalcitrant nodules and tunnels.82

Dosage and duration of treatment

Single triamcinolone acetonide 10–40 mg/mL injection in individual lesions was given either as monotherapy or in combination with systemic treatments.83 Ultrasonography can be used to guide the injection of triamcinolone and to assess the response to treatment.84 In case of no response, follow-up triamcinolone injections can be administered in periods ranging from 1 week and 3 months.85

Response rate

Systemic corticosteroids

Indication

High-dose systemic corticosteroids have been shown to be effective in treating acute flares but have been associated with exacerbations when tapering the dose.87 Care should be taken during pregnancy due to the potential risk of neonatal adrenal suppression.88

Dosage and duration of treatment

Ten milligram per day prednisolone equivalent p.o. could be used as an adjunct treatment of refractory disease.7 Short-term, higher dose prednisolone equivalent p.o. (0.5–0.7 mg/kg/day) may be effective in acute flares; the dose should be rapidly tapered.82

Response rate

Limited case reports and case series are available regarding the use of systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of HS. Eleven/13 patients with recalcitrant HS showed a clinical response to 10 mg/day prednisolone as an adjunct therapy, as evaluated by PGA at 2- to 4-week intervals.89 In 16 patients with moderate-to-severe HS treated with prednisolone, at a median dose of 0.44 mg/kg/day for a median period of 30 days as an adjunct treatment for disease control or preoperative care, a HiSCR achievement of 70% and an IHS4 reduction in 40% of patients were reported.90 In addition, a significant reduction in median pain NRS and DLQI was observed in 74% and 19% of patients, respectively. Three patients experienced a remarkable disease worsening after steroid cessation.

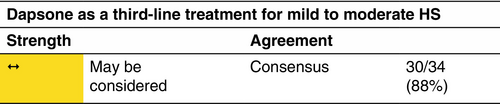

Dapsone

Mechanism

Dapsone (4,4′-diaminodiphenyl sulphone) is a sulphone drug with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. Antibacterial activity is mediated through inhibition of dihydrofolic acid synthesis; the mechanism of anti-inflammatory activity is less well defined.

Indication

Patients with mild-to-moderate disease (according to the IHS4 classification). Therapy should be initiated where standard first or second-line agents fail. Dapsone is not teratogenic but should be avoided during breast feeding.

Dosage and duration of treatment

T–200 mg/day for a minimal duration of 3 months and a maximum reported range of 3–48 months.

Response rate

Colchicine

Colchicine is a natural alkaloid extracted from plants of the lily family, including Colchicum autumnale.

Mechanism

Colchicine has both antimitotic and anti-inflammatory effects.

Dosage and duration of treatment

0.5–2.5 mg/day.92

Response rate

In an open prospective study with 20 patients, a combination of colchicine 0.5 mg/day and minocycline 100 mg/day led to improvement in every score after 3 months and the improvement persisted over time.93 In a retrospective analysis of 44 patients divided into three groups (colchicine monotherapy 1 mg/day, colchicine and doxycycline 100 mg/day and colchicine and doxycycline 40 mg/day), colchicine was assessed effective both alone and in combination.94

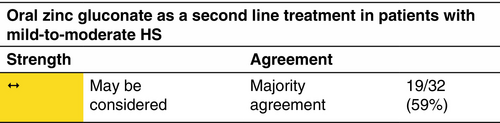

Zinc gluconate

Mechanism

Zinc has antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties.95

Indication

Zinc may be considered as a second-line maintenance treatment in mild-to-moderate HS. Zinc supplementation can be administered in zinc deficient patients. A prospective case–control study showed significantly lower serum zinc levels in 122 HS patients with mild-to-moderate HS compared with 122 controls (p < 0.001).96 Low zinc levels were also associated with more severe HS and lower DLQI.

Dosage and duration

90 mg/day zinc gluconate p.o. at initiation, may be lowered according to results and gastrointestinal tract side effects: long-term treatment.

Response rate

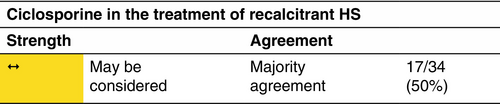

Ciclosporine

Mechanism

Ciclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor with potent immunosuppressive activity. It specifically targets T lymphocytes, suppressing both the induction and proliferation of T-effector cells and inhibiting production of cytokines (TNF-α and IL-2).

Indication

Ciclosporine should be reserved to cases where failure of response to standard first-, second- and third-line therapies occurs.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Ciclosporine 2–6 mg/kg/day has been administered for variable duration (6 weeks–7 months).100 There are limited data assessing appropriate dose or duration in HS treatment.

Response rate

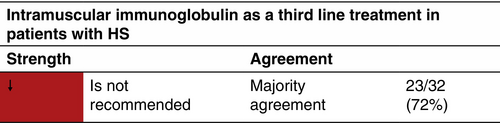

Immunoglobulin

Mechanism

γ-Globulin exhibits immune-modulatory actions.102 Immunomodulation is primarily used to decrease inflammatory reactions by controlling various, mainly antibody-mediated, components of the immune mechanisms.

Indication

Chronic recalcitrant HS.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Human immunoglobulin administered at a dose of 12.38 mg/kg i.m. monthly for 1–15 months.

Response rate

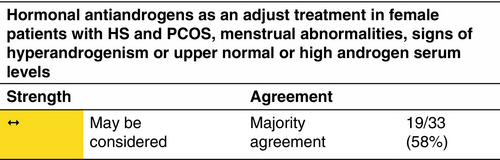

HORMONAL TREATMENT OF HS

There is an ongoing debate on the role of sex hormones in the pathogenesis of HS. Arguments in favour are that the first signs of the disease coincide with the start of the menstrual cycle and that many female patients experience perimenstrual flaring of the disease or during pregnancy.104, 105

Hormonal antiandrogens

Limited clinical studies showed that antiandrogens, such as cyproterone acetate and oestrogens, improve HS, while progestogens induce or worsen a pre-existing HS due to their androgenic properties.106-108

Indication

Female patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), menstrual abnormalities, signs of hyperandrogenism or upper normal or high serum levels of dehydroepiandrosterone, androstenedione and/or sexual hormone-binding protein.109

Response rate

Spironolactone

Spironolactone is a synthetic anti-mineralocorticoid with antiandrogen, gestagen, oestrogen and glucocorticoid effects.111 It is more commonly known as a potassium-sparing diuretic compound.

Dosage and duration of treatment

100 mg/day (50–150 mg/day) spironolactone p.o. There is no standard dose for the treatment of HS. To limit side effects, a starting dose of 25 or 50 mg/day is subsequently increased after a few weeks. There is no enough evidence for recommendation in HS treatment.

Response rate

Responses to spironolactone are usually registered within 3 months.111 A retrospective study of 67 women received 25–200 mg/day spironolactone (average dose 75 mg/day) followed for an average of 7 months exhibited improvement in pain, inflammatory lesion count and physician-assessed disease severity.

BIOLOGICS

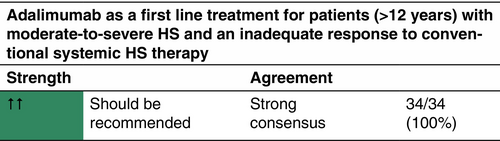

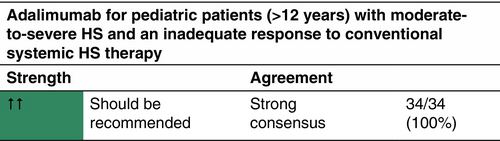

Adalimumab

Mechanism

Adalimumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody corresponding to the human immunoglobulin IgG1. It binds with high affinity and specificity to soluble and membrane-bound TNF-α and blocks its biological activity.

Indication

Adalimumab is a European Medicines Agency (EMA)- and FDA-approved drug for the treatment of active moderate-to-severe HS indicated for patients >12 years with an inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy. Antibiotics may be continued during adalimumab treatment.

Dosage and duration of treatment

The approved dosage for HS is (a) for adults: adalimumab 160 mg on Day 1, 80 mg on Day 15 and from Day 29, 40 mg each week or 80 mg every 2 weeks. If adalimumab is discontinued, it can be reintroduced with 40 mg each week or 80 mg every 2 weeks. (b) For patients ≥12 years and ≥30 kg: 80 mg Day 1, followed by 40 mg every 2 weeks starting Day 8. If effect is not achieved, adalimumab can be administered at 40 mg each week or 80 mg every 2 weeks. Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous (s.c.) injection. There is no dose adjustment for patients with obesity (>100 kg). In patients with less than 25% improvement in AN count after 12 weeks, treatment with adalimumab should be discontinued. For patients who do not achieve HiSCR, but achieve a 25%–50% improvement in AN count (partial response) after 12 weeks, continuation for 3 more months should be considered, since it has been shown that 73% of partial responders achieved HiSCR at Week 12.112 Following discontinuation of treatment, recurrence can occur after a median of 11–12 weeks.10

Response rate

Adalimumab biosimilars

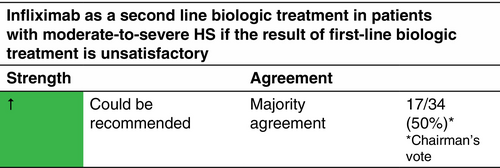

Infliximab

Mechanism

Infliximab is a chimeric (mouse/human) monoclonal antibody. It binds specifically to both soluble and transmembrane, receptor-bound TNF-α. Soluble TNF-α is ligated and its proinflammatory activity is neutralized. Infliximab has a serum half-life of about 8 to 9.5 days. The elimination period is up to 6 months. Infliximab is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). Infliximab is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Infliximab 5 mg/kg i.v. at Weeks 0, 2 and 6, and subsequently every 8 weeks.

Response rate

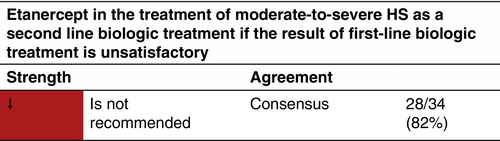

Etanercept

Mechanism

Etanercept is a fusion recombinant protein, which fuses the TNF receptor and inhibits TNF-α binding.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (accordin.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Etanercept 50 mg 2×/week s.c.

Response rate

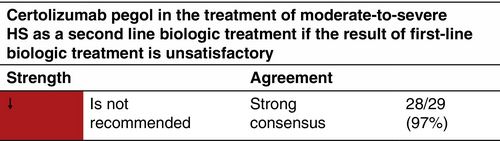

Certolizumab pegol

Mechanism

Certolizumab pegol is a recombinant, humanized monoclonal antibody against TNF-α.

Indication

Active moderate-to-severe HS.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Certolizumab pegol 400 mg s.c. every 2 weeks.

Response rate

Secukinumab

Several studies have demonstrated increased levels of Th17 cells and overexpression of IL-17 in HS, providing a rationale for IL-17 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy.123-126

Mechanism

Secukinumab is a human monoclonal antibody against IL-17A.

Indication

Secukinumab is a medicinal product approved by the EMA and the FDA for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe active HS with inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy.11

Dosage and duration

The approved dosage for HS is 300 mg with initial doses in the Weeks 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, followed by monthly maintenance doses. Based on the clinical response, the maintenance dose may be increased to 300 mg every 2 weeks. Secukinumab is administered as a s.c. injection.

Response rate

Bimekizumab

Mechanism

Bimekizumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG antibody of full length selectively inhibiting both IL-17 and IL-17F. The inhibition of both cytokines might produce an additional effectiveness in HS.128

Indication

Bimekizumab is a medicinal product approved by the EMA for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe active HS with inadequate response to conventional systemic HS therapy.12

Dosage and duration of treatment

The approved dose is 320 mg s.c. every 2 weeks for 16 weeks and then every 4 weeks after. Bimekizumab is administered as a s.c. injection.

Response rate

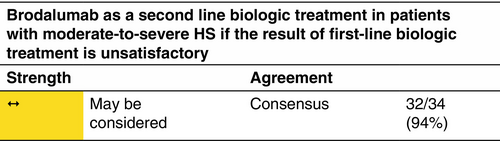

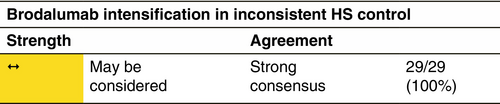

Brodalumab

Mechanism

Brodalumab is a human, monoclonal antibody against the IL-17 receptor.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). Brodalumab is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Brodalumab 210 mg s.c. every 2 weeks.

Response rate

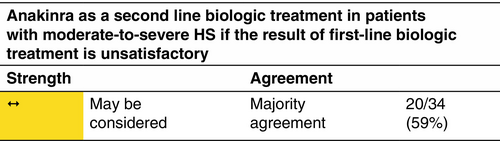

Anakinra

IL-1 is a proinflammatory cytokine that has been shown to be highly upregulated in lesional HS skin, probably as a result of activation of the inflammasome, making it a target for treatment in HS.131

Mechanism

Anakinra is a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist. It blocks the biological activity of naturally occurring IL-1 by competitively blocking the binding of both IL-1α and IL-1β to the IL-1 type 1 receptor.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). Anakinra is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

100 mg/day s.c.

Response rate

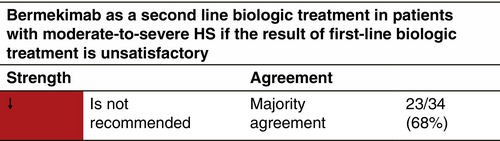

Bermekimab

Mechanism

Bermekimab is a human monoclonal antibody that neutralizes IL-1α by binding this cytokine with high affinity, thereby neutralizing IL-1α activity.

Indication

Active moderate-to-severe HS.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Bermekimab 7.5 mg/kg i.v. every 2 weeks/400 mg s.c. weekly.

Response rate

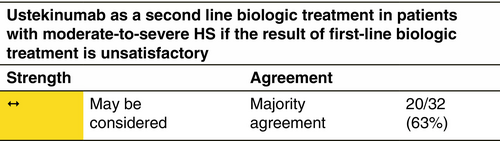

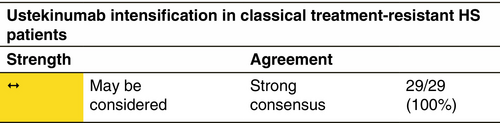

Ustekinumab

Mechanism

Ustekinumab is a recombinant, fully human IgG1 antibody. It binds with high specificity and affinity to the common p40 subunit of the cytokines IL-12 and IL-23.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). Ustekinumab is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dose and duration of treatment

Ustekinumab 45 mg s.c. (in patients with a body weight >100 kg, 90 mg s.c.) at Weeks 0, 4, 16 and 28. [Correction added on 8 March 2025, after first online publication: unit "mg/week" has been revised to “mg”.]

Response rate

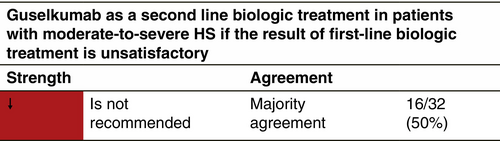

Guselkumab

Mechanism

Guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to the p19 subunit of IL-23.

Indication

Active moderate-to-severe HS.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Guselkumab 200 mg s.c. or 1200 mg i.v. every 4 weeks.

Response rate

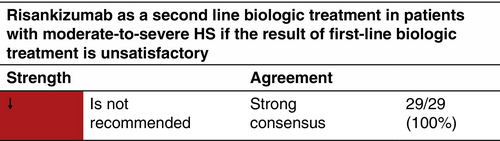

Risankizumab

Mechanism

Risankizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets IL-23A.

Indication

Active moderate-to-severe HS.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Risankizumab 150 mg at Week 0, 4 and every 12 weeks.

Response rate

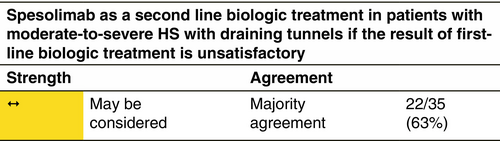

Spesolimab

Mechanism

Spesolimab is an anti-IL-36 receptor monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits IL-36 signalling.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according tio the IHS4 classification) with draining tunnels. Results of phase III studies are awaited. Spesolimab is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

A double-blind RCT proof-of-clinical-concept study was conducted with 52 moderate-to-severe HS patients randomized (2:1) to receive a loading dose of 3600 mg spesolimab i.v. (1200 mg at Weeks 0, 1 and 2) or matching placebo, followed by maintenance with either 1200 mg s.c. every 2 weeks from Weeks 4 to 10 or matching placebo.145

Response rate

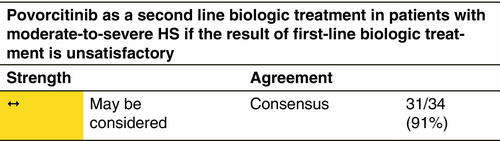

Povorcitinib

Mechanism

Povorcitinib is an oral, selective Janus kinase (JAK)1 inhibitor with approximately 52-fold greater selectivity for JAK1 versus JAK2.146 It was shown to regulate genes and impacted JAK/STAT signalling transcripts downstream of TNF-α signalling or those regulated by tumour growth factor (TGF)-β.147

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). Results of phase III studies are awaited. Povorcitinib is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Two phase 2 dose-escalation RCTs were conducted in 35 and 209 moderate-to-severe HS patients randomized to povorcitinib 15–180 mg/day or placebo for 8–12 weeks with a 30-day safety follow-up period at the end of treatment.146, 148

Response rate

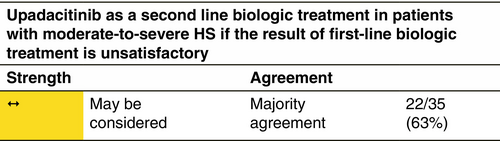

Upadacitinib

Mechanism

Upadacitinib is an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor with high selectivity for JAK1 and its signal transduction molecules.

Indication

Moderate-to-severe HS (according to the IHS4 classification). No phase II or III studies have been published. Upadacitinib is not approved for the treatment of HS by the EMA or the FDA.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Upadacitinib 15 mg/day up to Week 4. If the clinical response is not sufficient after 4 weeks, treatment doses might be increased to 30 mg/day.149

Response rate

ELIGIBILITY FOR BIOLOGICS AND ADVANCED MOLECULES

Treatment of HS includes the use of biologic and small molecule drugs for patients with moderate and severe forms of disease. Identifying patients who are candidates for this type of treatments is important to avoid delays in treatment or under treatment that could lead to disease progression or reduced effectiveness.150, 151 The prescription of biologic drugs or advanced therapies/small molecules should always be carried out in accordance with the indications in the drug label and the therapeutic algorithm described in this guide, if in any case these conflict with the following eligibility criteria, the information in the drug label will prevail.

The presence of one or more of the following criteria may be used to identify patients who are candidates for treatment with biologics and advanced molecules (Table 2).4, 6, 113, 151-155 These criteria should serve as a generic guideline; each case should be analysed individually to choose the most beneficial treatment modality for the patient according to his or her clinical characteristics and personal preferences.

| Criteria | Value | References |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate-to-severe objective disease severity |

IHS4 ≥4 or HS-PGA ≥3 (moderate) or Refined Hurley: IC, IIB, IIC, III or Increase in Hurley stage |

[4, 6, 113, 151] |

| Significant impairment of quality of life |

DLQI >10 or HS-QoL >20 |

[152, 153] |

| Clinical signs of unstable/progressive disease |

Several outbreaks per year or Rapidly progressive disease or Extensive disease |

[154] |

| Special clinical scenarios |

Special locations: genital area, face, scalp, neck or Signs of local complications: lymphedema |

[155] |

RETINOIDS

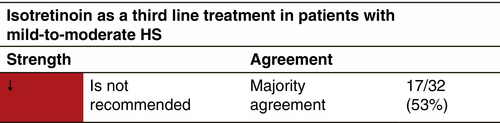

Isotretinoin

Mechanism

The main activity of isotretinoin in HS might be the prevention of an affected pilosebaceous unit from being occluded by ductal hyper-cornification. In addition, isotretinoin has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties.156 It might directly modify monocyte chemotaxis and exert secondary effects with regard to anti-keratinizing action and avoidance of hair follicle rupture. Reduction in sebaceous gland size and inhibition of sebaceous gland activity (responsible for the rapid clinical improvement observed in acne vulgaris) seem not to be of relevance in the treatment of HS as an absence or reduced volume of the sebaceous glands are observed in HS.157

Indication

Its usage in HS is often disappointing and the reported data are inconsistent.158

Dosage and duration of treatment

0.5–1.2 mg/kg/day administered within the period of 4–12 months.158-164

Response rate

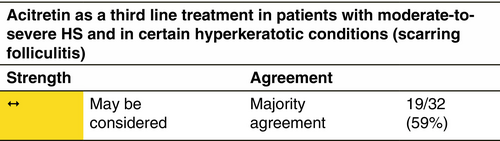

Acitretin

Mechanism

Acitretin is a metabolite of etretinate and has replaced it in the treatment of various skin disorders since it is equally effective and has a much shorter elimination half-life. Acitretin reduces the keratinocyte rate of proliferation and dermal and epidermal inflammation by inhibiting polymorphonuclear cell chemotaxis and release of proinflammatory mediators.169

Indication

Acitretin might be used in early HS stages and in the presence of prominent hyperkeratotic follicular lesions.170, 171

Dosage and duration of treatment

Acitretin 0.25–0.50 mg/kg/day for 3–12 months.

Response rate

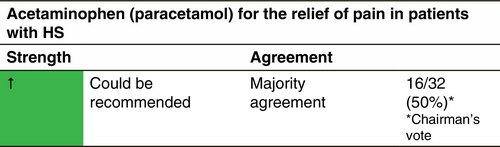

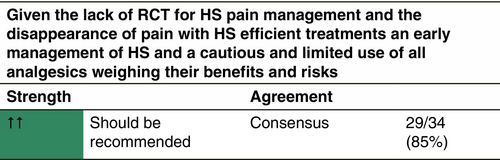

ANALGESICS

Pain is the main symptom in HS disease and relief of this pain should be the primary objective of all treatments, as well as clinical improvement of lesions. No randomized controlled trials with analgesics for HS have been published. More than only a symptomatic therapy purely against pain, an efficient treatment targeted against HS disease itself should be preferred, since it seems more efficacious in the long and short term on the pain component. However, before these treatments can completely remove pain in HS patients, symptomatic analgesia might be useful.

Acetaminophen (paracetamol)

Indication

This molecule should always be tried in the first place for pain relief, due to its good tolerance profile and low number of contraindications. However, it may be insufficient for relieving the important pain encountered by severe HS patients, justifying combinations of acetaminophen with codeine and/or caffeine to increase efficacy.

Dosage and duration of treatment

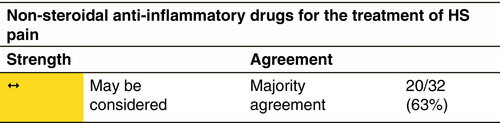

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)

Indication

There is no proof of the efficacy of NSAID in HS. However, these molecules are regularly used by HS patients.

Response rate

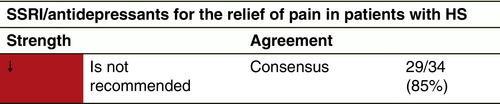

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI/antidepressants)

Indication

Duloxetine is an SSRI/selective serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI) that is used to treat major depressive disorders, general anxiety disorders, painful peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain and chronic lower back pain.175

Venlafaxine has not been studied for HS pain.176

Dosage and duration of treatment

Duloxetine: 60 mg/day. Venlafaxine: 75 mg/day (maximum 375 mg/day); possibility to dose increase, taking into account safety profile and tolerability.

Response rate

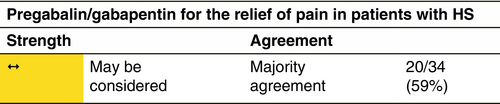

Pregabalin/gabapentin

Mechanism

Gabapentin and pregabalin bind to the α2δ subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel in the central nervous system and affect γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels. They decrease the release of neurotransmitters, including glutamate, noradrenaline, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Indication

Gabapentin and pregabalin are used to relieve neuropathic pain.177, 178 They change neural thresholds, thereby decreasing pain.

Dosage and duration of treatment

The gabapentin starting dose is 2 × 50 mg/day (300 mg/day on Day 1, 600 mg/day on Day 2, 900 mg/day on Day 3, divided into three doses). Additional titration to 1800 mg/day is advisable for greater efficacy. Doses up to 3600 mg/day can be required in some obese patients. Pregabalin starting dose in HS patients is 50 to 2 × 50 mg/day, to increase gradually to 2 × 100 mg/day. The effective dose should be individualized.

Response rate

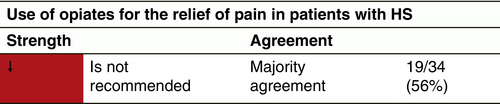

Opiates

Indication

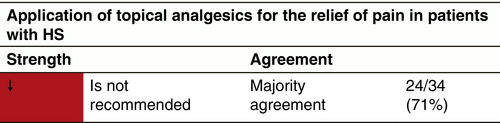

Topical analgesics

Diclofenac

Dosage and duration of treatment

The topical preparations are diclofenac sodium 1.5% topical solution, diclofenac sodium 1% gel and a diclofenac hydroxyethylpyrrolidine 1.3% patch. Gentle rubbing in diclofenac 1% gel for 45 sec seems to increase its penetration into the epidermis. Duration should be 1–2 weeks.

Xylocaine

Indication

Temporary relief of pain and itching. Liposomal or micronized versions of xylocaine seem to maximize cutaneous effects and minimize systemic effects.

Dosage and duration of treatment

Topical xylocaine 1 or 2×/day is a mainstay of short-term (1–2 h) topical pain treatment.179

Capsaicin

Mechanism

Capsaicin selectively binds to the vanilloid receptor 1 primarily expressed on C-nerve fibres that release substance P.180

Dosage and duration of treatment

EXPERIMENTAL THERAPIES

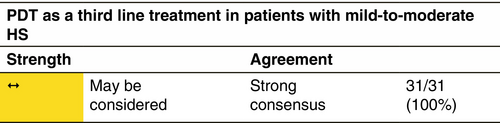

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

Mechanism

The mechanism of action of PDT for HS remains largely unknown. Indeed, PDT has (i) a direct cytotoxic effect on cells, (ii) antimicrobial effects and (iii) a role in the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines.181, 182

Response rate

PDT has been used to treat HS with conflicting results.

Blue light PDT

Three studies evaluated the use of blue light PDT with 20% 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) in 18 patients after an incubation period ranging from 15 min to 1.5 h.183-185 Complete response was assessed in three (16.7%) patients.185

Red light PDT

Five studies with 21 patients have evaluated the use of red light PDT applying 5% to 20% ALA. Six (28.6%) patients experienced a moderate improvement with some of them relapsing after treatment discontinuation.186-190 In a study using methylene blue in nanosomes and intense pulsed light with 630 nm filter as a light source, promising results were shown in 11 patients.191 Another study with six patients used methyl aminolevulinate and red light as light source with an incubation period ranging from 3 to 4 h leading to marked or moderate response in five out of six patients.192

Intralesional PDT (iPDT)

The use of PDT with a 630 nm intralesional diode and 1%–5% ALA was evaluated in four studies (three retrospective, one open prospective) with 110 patients.190-193 In 53/68 (83.8%), moderate to complete remission was achieved. In 42 patients, a high percentage of lesion resolution or improvement was observed.193 Two further studies used intralesional methylene blue 1% solution as photosensitizer, injected into HS lesions with ultrasonography guidance in 48 patients and illuminated with a 635 nm red light-emitting diode lamp after an incubation period of 15 min.194, 195 In the first study, 5/7 patients (71%) improved and maintained HS remission of HS in the treated area.194 In the second study, a reduction of ≥75% in the maximum lesion diameter was reported in 24/41 (58.5%) patients.195

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) PDT

One study evaluated the use of PDL-mediated PDT in the treatment of four HS patients. Three months after the end of the treatment, no lesion improvement was recorded.196

PDT combined with surgery

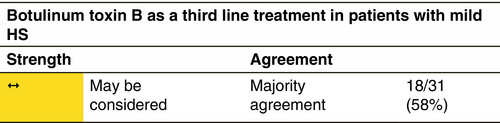

Botulinum toxin B

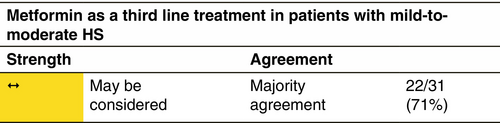

Metformin

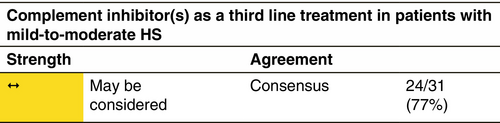

Complement inhibition

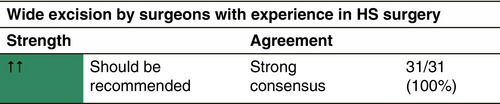

SURGERY

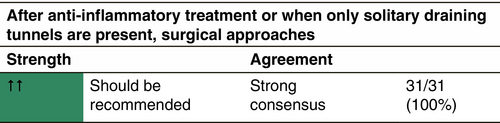

Within the chronic inflammatory skin diseases, HS is characterized by a disease progression with a shift from inflammatory skin lesions to irreversible tissue destruction, which is no longer adequately responding to medical treatment options, due to the presence of biofilms within scars. Therefore, surgery plays an important role within the therapeutic armamentarium, a fact that distinguishes HS from other inflammatory skin diseases, such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. Like the stepwise approach of medical treatments, surgery is escalated with higher disease severity and more irreversible tissue damage like tunnels and scarring.

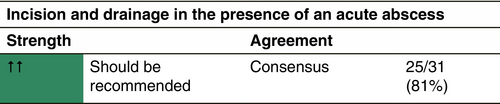

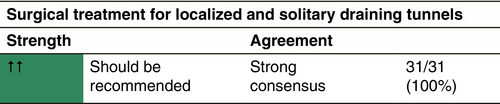

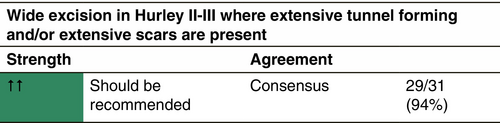

Conventional surgery

In acute abscess formation, incision and drainage are useful options followed by a mandatory medical or further surgical treatment. In more severe disease, a larger removal of damaged tissue is indicated. Several surgical techniques co-exist and are in current use (Table 3).204-209

| Technique | Number of treated patients or meta-analysis studies | Recurrence rate (%) | Follow-up period | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deroofing | 44 patients | 17 | Median 3 years | [204] |

| CO2-LASER evaporation | 58 patients | 29 | 1 year | [205] |

| CO2-LASER excision | 61 patients | 1.1 | 1 to 19 years | [206] |

| Wide excision | 63 patients | 24 | 5 years | [207] |

| 97 studies | 5 | Median 2 years | [208] | |

| 33 studies | 8 | Mean 3 years | [209] |

Post-surgical conventional surgery healing

It is difficult to compare surgical and post-surgical treatment modalities for HS because of the complex nature of the disease, the numerous complicated surgical interventions used for treatment and the variable results reported in the literature.

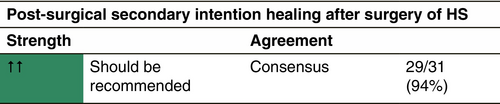

Post-surgical secondary intention healing (SIH)

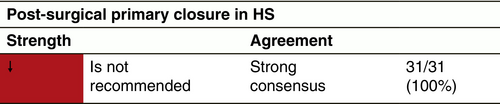

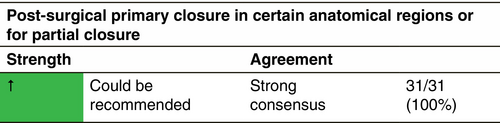

Post-surgical primary closure

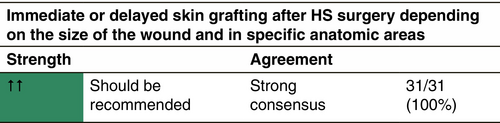

Post-surgical reconstruction with immediate or delayed skin grafting

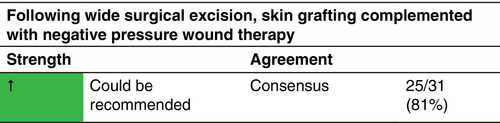

Post-surgical reconstruction with skin grafting and negative pressure wound treatment (NPWT)

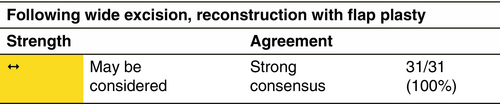

Post-surgical reconstruction with flap-plasty

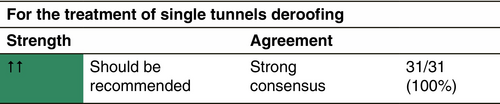

Deroofing

Deroofing, sometimes called unroofing, is a limited surgical intervention in HS, where only the roof of the tunnels is removed leaving behind the epithelized floor of the tunnels. Unfortunately, the term is heterogeneously used by clinicians for describing also limited excision under local anaesthesia. There is limited evidence on prospective data of deroofing in HS. Most data are based on retrospective case series. The deroofing technique is an effective and fast surgical technique can be easily performed under local anaesthesia, and therefore, it is suitable as an office-based surgical procedure preferably in Hurley stage II.219 With limited surgery and maximal preservation of the surrounding healthy tissue, painful recurrent lesions are converted into cosmetically acceptable scars, with few postoperative complications.219, 220

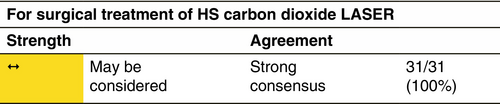

Carbon dioxide LASER therapy

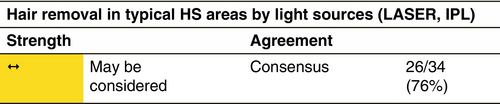

Energy-based therapies directed against the hair follicle

Based on the assumption that the hair follicle plays an important role in HS pathogenesis, LASERs and intense pulse light (IPL) devices designed for hair removal have been studied in HS. The efficacy of hair removal devices is based on the principle of selective photothermolysis, in which thermally mediated radiation damage is confined to targets at the hair follicles.230

Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) LASER therapy

The Nd:YAG LASER (1064 nm) can facilitate depilation and has been used for treatment of HS.31, 231-233 The idea to use depilation in order to control HS, especially the development of new lesions, in light of the pathogenesis, seems plausible. However, the number of studies is scarce and not of high quality.

IPL therapy

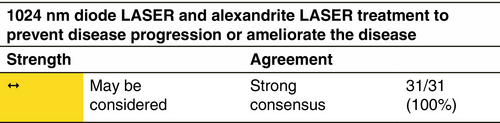

Diode and alexandrite LASER treatment

COMBINATION TREATMENTS (MEDICAL/MEDICAL, MEDICAL/SURGICAL)

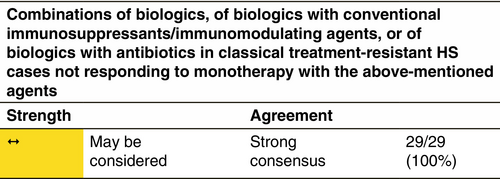

HS is an extremely difficult to treat chronic inflammatory disease. Current monotherapies do not often provide satisfying clinical results. This could be explained by a higher inflammatory load compared with other skin diseases, and/or the not yet fully understood complex multi-pathway disease pathogenesis. Regarding the above-mentioned points, a combined treatment targeting multiple inflammatory pathways or multiple pathogenic axes could be a promising approach to achieve better clinical results. However, no prospective studies on the efficacy of pharmaceutical combinations compared with monotherapy for HS have been conducted yet.

Despite the lack of prospective trials, the PIONEER adalimumab trials might suggest that adalimumab in combination with a tetracycline group antibiotic could be slightly more efficient than adalimumab alone (see chapter ‘Adalimumab’).10 Furthermore, in a small retrospective study the combination of colchicine with doxycycline showed tendency to higher efficacy compared with colchicine alone (see chapter ‘Colchicine’).94 Yet, another retrospective case series showed favourable results for the combination therapy of zinc gluconate and topical triclosan for Hurley stage I disease (see chapter ‘Zinc gluconate’).30 Since we continue to struggle to achieve satisfying results in this complicated multifactorial disease, the possibility of combining pharmaceutical therapies (different inflammatory pathways, bacterial or follicular plugging) should be further explored.

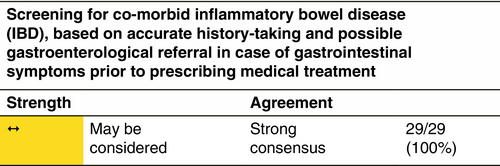

Anakinra and other biologic agents, particularly infliximab and adalimumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab and tildrakizumab have been used, usually achieving incomplete control both of HS and associated conditions.238-241 Combination of infliximab, classical immunosuppressants, like cyclosporine and immunomodulating agents, such as dapsone, has also been tried, obtaining substantially similar results.242

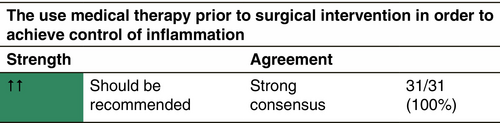

Combining surgery with medical treatments

Surgery and systemic medical treatments have different but complementary purposes: effective in eliminating HS lesions (ideally) definitively, surgery remains a local treatment, whereas systemic medical treatments aim at a global control of the inflammation, without ensuring a complete and definitive control, especially when they are stopped. Their association is therefore logical (both controlling the whole disease and locally getting rid of one or more particularly persistent or disabling lesions), but there is a clear lack of high-quality studies on this specific subject. Additionally, comparison of studies containing surgical procedures are often biased, as internationally accepted definitions of surgical techniques and outcome measures such as recurrence are frequently missing.

There is little documentation on the combination of surgery and antibiotics. Provided that the contraindications and spectrums of action are respected, there is no reason to believe that the combination of antibiotics and surgery, which is usual in many medical and surgical activities, poses any concerns about postoperative complications. Only ertapenem (1 g/day i.v. for 1 to 18 weeks) has been specifically described as a rapid and effective way to improve symptoms in severe forms of HS and proposed as a bridge to surgery (in the absence of Pseudomonas against which it is not active).57, 58

The combination of biologics and surgery is a little bit more debated, mostly because of the expectation that biologics could be used as a drug preparation for surgery. The theoretical goals are then, through (intuitively appropriate) preoperative control of inflammation, to (1) reduce indications for surgery, (2) limit the extent of surgery and (3) improve surgical outcomes (reduce the local recurrence rate). There is only limited data in the literature to suggest that the theoretic third objective may be achieved by perioperative biologics.13, 212, 244-247 In a comparison of 21 patients undergoing combined surgery and then biologic therapy versus surgery alone, the combination showed lower rates of recurrence/disease progression (19% vs. 38.5% for surgery alone; p < 0.01). New disease developed in 18% and 50% of combined treatments and surgery-only groups, respectively. The disease-free interval was also higher in the combination group (18.5 vs. 6 months; p < 0.001).212

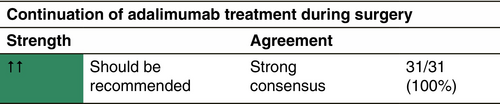

Combination with surgery is well supported by a phase 4, randomized, double-blind RCT of adalimumab in conjunction with surgery.13 Two hundred and six patients with moderate-to-severe HS requiring radical surgery (Hurley stage III) in an axillary or inguinal region and two other anatomical regions affected were randomized 1:1 to receive adalimumab 40 mg s.c. once weekly or placebo during pre-surgery (12 weeks), perioperative (2 weeks) and postoperative (10 weeks) periods. At Week 12, 49/103 (48%) patients receiving adalimumab versus 35/103 (34%) under placebo (p = 0.049) achieved HiSCR across all body regions. No increased risk of postoperative wound infection after wide-excision surgery followed by secondary intention healing, complications or haemorrhage was observed with adalimumab versus placebo.238-241 Antibiotics may be continued during biologic therapy.

TREATMENT OF DRAINING TUNNELS

WOUND CARE

General measures

Draining tunnels and rupture of abscesses with discharge of malodorous pus negatively impact quality of life in HS.250 Appropriate wound care is an important domain of HS management as it improves patients' quality of life.251 Most recommendations are based on general wound care guidelines and expert opinion. In chronic wound care, the choice of dressing is based on the affected body region, the absorption capacity, the sufficient adherence of the dressing and the fixation material.250 Usually, the most suitable wound dressings are superabsorbent foams alone or in combination with alginates, atraumatic adhesives such as silicone and nonadherent dressings (Table 4).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In postoperative wound care, there is a lack of evidence on wound care strategies. Current knowledge is based on observational studies and case series.223, 252 Postoperative wound care in HS is dependent on the closure techniques, whether primary or secondary closure, skin grafting or transposition flap and on the anatomical region of the intervention.253 Local surgical guidelines and wound care are mostly followed.253, 254 Relatively large postoperative wounds producing higher volumes of exudate may benefit from negative pressure wound therapy.

Negative pressure therapy

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS

Weight management

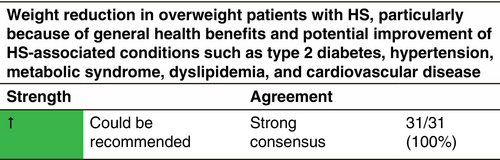

Obesity is strongly associated with HS, with a systematic review confirming an odds ratio of 3.45 (95% CI 2.20–5.38) for the association.255 A BMI has been linked to greater disease severity256 and a BMI increase of one unit was associated with a 0.84 unit increase in mean Sartorius severity score.257 There is no RCT to confirm whether weight reduction in obese HS patients reduces disease severity. In a retrospective case series of 12 patients, substantial weight loss from bariatric surgery improved HS relative to a control group.258 In some cases, residual excess skin folds may cause ongoing skin problems. While the evidence regarding weight reduction in obese HS patients remains equivocal, it is advisable because of the general health benefits and potential improvement of HS-associated conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidaemia and cardiovascular disease.259 Regular physical activity may help in maintaining or losing weight, as well as improving the metabolic alterations associated with obesity. The development of glucagon-like peptide analogues, which are approved by the EMA for the treatment of obesity, may have important implications for HS treatment. One retrospective study of the adjunctive use of semaglutide in HS patients showed a beneficial reduction in HS flares and an improvement in quality of life.182

Smoking cessation

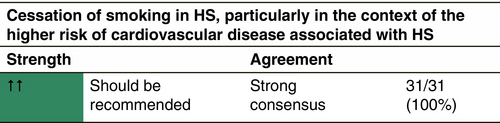

Tobacco smoking is consistently associated with HS, a systematic review finding an odds ratio of 4.34 (95% CI, 2.48–7.60) for the association with current smoking.255 There is some evidence to suggest a dose–response with greater smoking pack years linked to more severe HS.256 However, an increase in disease recurrence following surgery for HS in current smokers has not been demonstrated in most studies.259 Similarly to weight reduction, there is no RCT providing evidence of the effect of smoking cessation on HS severity. Nevertheless, the overall health benefits of smoking cessation, particularly in the context of the higher risk of cardiovascular disease associated with HS, means that smoking cessation, where relevant, is advisable.

Dietary modification

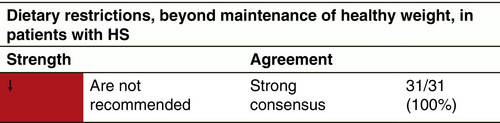

Dietary modification and supplements have been investigated in a few small studies; however, the evidence is insufficient to make a specific recommendation beyond maintaining a healthy weight. A prospective cohort study followed 12 patients undergoing surgery for HS who adhered to a diet free from Brewer's yeast for 12 months; however, the effects of the diet cannot be distinguished from the effects of surgery, and there was no control group.260 Dairy-free or dairy-restricted diets have been investigated in an uncontrolled retrospective cohort study and a case series, however the evidence quality is classified as very low.261 A pilot study found that all 22 HS patients were deficient in vitamin D and supplementation produced improvement in 11/14 individuals after 6 months.262

Avoidance of friction

LONG-TERM TREATMENT

Long-term treatment in HS should be considered and defined as more than 6 months. Long-term treatment definition also includes a maintenance phase of treatment (see chapter ‘Maintenance treatment’). Long-term continuous treatment with adalimumab (data of at least 2 year of continuous use) maintains a level of sustained effectiveness (on physician signs, pain and quality of life) in responders with an acceptable safety profile.112

MAINTENANCE TREATMENT

A maintenance phase of treatment in the dermatological field is usually intended as the one that follows the active phase of treatment when a defined clinical result has been achieved. The aim of the maintenance treatment is to maintain the acquired results and to prevent recurrences of the disease. Regarding the concept of maintenance therapy in HS, no acknowledged and shared definition can be found in the literature. Specific relevant publications do not exist, except for citing the concept of maintenance.

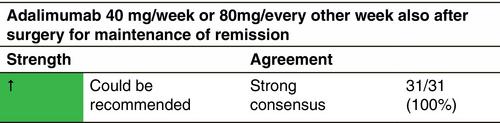

Using PIONEER integrated trial results, the optimal medium-term maintenance dosing strategy for adalimumab in moderate-to-severe HS has been evaluated.264 Maintenance treatment was defined as a therapy that can be used after achieving remission (achievement of HiSCR at Week 12) in order to prevent progression and flare ups (i.e. HiSCR loss). Adalimumab 40 mg/week, effective throughout 36 weeks, was the optimal maintenance medium-term dosing regimen for this population. After at least partial treatment success with adalimumab weekly short-term therapy (12 weeks), continuing weekly dosing during the subsequent 24 weeks had better outcomes than dose reduction or treatment interruption. Patients who did not exhibit at least a partial response to weekly adalimumab by Week 12 were unlikely to benefit from continued therapy. In a recently published prospective multicentric study on 107 patients with HS, two different regimens, that is adalimumab 40 mg/week or 80 mg every other week were defined as maintenance treatment, with no statistically significant differences between them in the term of baseline–Week 32 outcomes of the IHS4, DLQI, pain VAS and PGA.265 In short-term studies, recurrence follow discontinuation of treatment after 11–12 weeks. Long-term (at least 2 years) continuous treatment maintains a level of consistent effectiveness in responders with an acceptable safety profile.112

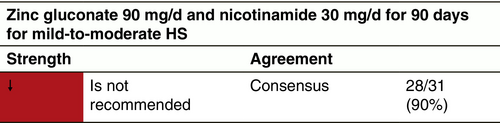

In another recent study, maintenance therapy for 92 mild-to-moderate HS patients after 12 weeks of beneficial treatment with tetracyclines p.o. was proposed with capsules containing 90 mg zinc gluconate and 30 mg nicotinamide once daily for 90 days.98 Disease-free survival was significantly longer in the treated group (vs. non-treated control group), and it showed sustained improvement even after discontinuation of oral supplementation.

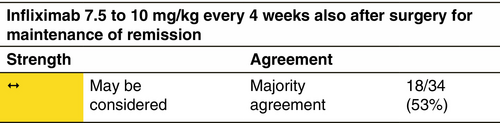

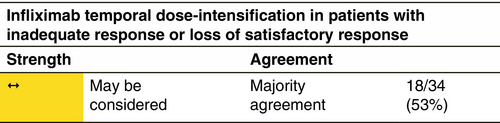

The efficacy of infliximab 7.5 to 10 mg/kg in HS patients has been evaluated in a study.266 The maintenance treatment every 4 weeks, was started when the outcome goals, referred to HS-PGA, NRS pain and MCIC QoL, were achieved. In this case, a well-defined type of clinical result was considered, but was variable, from full clearance to mildly severe disease still present.

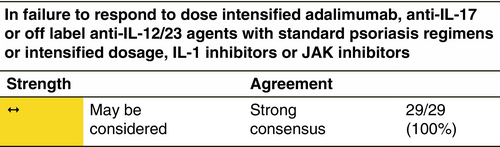

TREATMENT OPTIONS IN CLASSICAL TREATMENT-RESISTANT HS

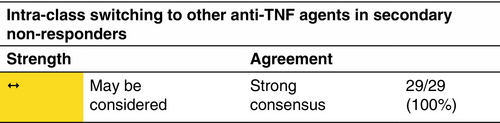

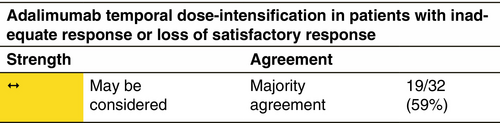

Loss of response appears to be a frequent concern in the long-term HS treatment with anti-TNF agents.268 At present, there is a lack of evidence in terms of clinical predictors and/or biomarkers guiding the choice among the different drugs and the decision is mainly based on the presence of comorbid conditions. Similarly, the decision to switch between different drugs is mainly based on lack or loss of response and/or the occurrence of adverse events, including paradoxical reactions.269 HS patients that either experience inadequate disease control or loss of response with adalimumab 40 mg/week or 80 mg/every other week are defined as classical treatment-resistant HS cases. According to the results of a retrospective case series of 14 patients that had been treated with adalimumab 40 mg/week, temporary administration of intensified adalimumab 80 mg/week treatment resulted in a significant reduction in IHS4 score.270 In a retrospective study on 22 patients with severe HS, who had experienced loss of response to adalimumab, dose intensification to adalimumab 80 mg/week resulted in the fulfilment of HiSCR in 68% at Week 12. Similarly, in a prospective study, that evaluated variable dose intensification regimens, that is adalimumab 80 mg every 10 or 12 days, in moderate-to-severe HS patients experiencing loss of response, 62% of participants achieved the HiSCR at Week 12.271

SYNDROMIC HS TREATMENT

Syndromic forms of HS, including pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH), pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis (PAPASH), psoriatic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis (PsAPASH), pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis and ankylosing spondylitis (PASS), and pustular psoriasis, arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, synovitis, acne and suppurative hidradenitis (PsAPSASH) represent paradigms of severe, treatment-refractory HS.274, 275 Due to their rarity, evidence on the treatment of these forms is very limited and consists mainly of isolated reports and small case series.

TREATMENT BIOMARKERS

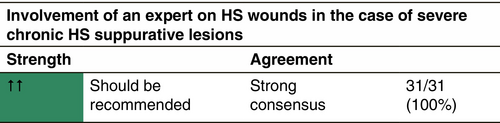

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

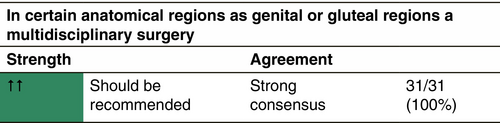

HS patients frequently present clinical patterns that are best addressed by specialists from multiple fields of medicine and surgery. A multidisciplinary approach refers to the co-ordination and collaboration of health care providers (HCP) with different specializations who work in parallel in order to improve the outcome of the patients.279 There is no available randomized or non-randomized clinical trial which demonstrates that the availability of a multidisciplinary approach improves the outcome of HS. A study in 49 patients showed that the level of satisfaction is increased by the patients when this multidisciplinary approach is provided in a parallel time.245 There is no doubt that patients are usually in need of consultation of several specialists for their primary disease, but also for their comorbidities.

THERAPEUTIC CONCLUSIONS AND ALGORITHM

Based on consensual recommendations, the expert group has outlined the following therapeutic algorithm of active inflammatory HS and inactive, predominantly non-inflammatory HS for the stage-related therapy of HS (Figure 1).

PATIENTS VIEW

Recommendations to HS patients

- Identify your most troublesome physical symptoms (such as pain, wound care, odour from wounds and fatigue), any HS-associated problems, factors that may worsen/help, and the best care solutions for these, whether these solutions involve medical treatment, support or others.

- Connect with, talk with, share with and learn from others, that is family, friends, other people with HS, HS groups, other patient groups and your medical team.

- Identify your main needs: disability, emotional, financial, mental, physical, relationships, sexual, social, study/work difficulties and so on.

- Try to identify the most appropriate care (i.e. medical treatments and supports), your training, becoming involved in HS research, sharing your lived experience with your medical team and other HCPs and others who have HS.

- Be kind to yourself and your body. A healthy lifestyle may improve your HS, for example stopping smoking, healthy diet, prioritizing rest, sleep and well-being, managing your stress, fresh air and natural daylight, and if possible, movement or exercise that you enjoy. Ask your medical team and others for help, resources and support if needed.

- An illness diary in conjunction with photographs can help to document the course of the illness. In this way, the doctor(s) can be informed about the course of the disease between medical consultations. This can also be helpful when dealing with the authorities.

Recommendations to HCP

- Address all the patients' symptoms and difficulties, including but not limited to pain, wound care, odour, fatigue, those related to comorbidities (including mental health support and well-being) and those related to financial and social impairments.

- Watch out for possible superinfections.

- Access to emergency care for patients is vital.

-

The first consultation is critical:

- ⚬

Use appropriate language and give an honest evaluation of the disease, treatment options and management expectations.

- ⚬

Highlight the increase in HS research and the many treatments in development.

- ⚬

Mention comorbidities, screening and management of these.

- ⚬

Suggestions about lifestyle changes (where appropriate) and any sensitive issues need not to be mentioned on the first visit. Establishing an honest, respectful and trusting relationship is conducive to this.

- ⚬

- Provide information about credible and reputable HS patient groups and associations, directory of HS practitioners, online HS resources and other relevant information.

- Promote patients' and HCP education through dedicated programmes using good instructional design principles and practices. Encourage intrafamilial communication by inviting relatives to consultations, especially the first.

- Support shared decision making, considering the patient's history and their wishes for treatments, surgery, lifestyle adjustments (if needed) and other measures.

- Promote patient involvement in research.

- Collaborate with all the main stakeholders in the care process: medical and paramedical HCP, the patient and their network, patient associations, industry, health authorities, others.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have met the criteria for authorship, having made substantial contributions to the work and taking public responsibility for relevant portions of the content, as follows: Objectives of the guidelines, Objectives of HS treatment, What's new?, Overview of therapeutic options: Zouboulis CC. Scoring system for clinical trials: Tzellos T, Marzano AV and Molina-Leyva A. Adjuvant therapy: Szégedi A, Molina-Leyva A and Horváth B. Topical therapy—nonantibiotics: Bukvic Mokos Z, Dolenc-Voljc M and Bechara FG. Topical antibiotics: Zouboulis CC, Jemec GBE and Prignano F. Systemic antibiotics: Kemény L, van Straalen KR and Saunte DML. Consideration of bacterial resistance under long-term antibiotic treatment: Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Saunte and Nassif A. Anti-inflammatory treatment: Bukvic Mokos Z, Szégedi A, Prens EP, Zouboulis CC, Jemec GBE, Liakou AI, Dolenc-Voljc M, Valiukeviciene S and Kirby B. Hormonal treatment of HS: Bukvic Mokos Z, Prens EP and Szegedi A. Biologics: Prens EP, Tzellos T, Kirby B and Zouboulis CC. Eligibility for biologics and advanced molecules: Kirby B, Molina-Leyva A and Hunger RE. Retinoids: Zouboulis CC, Jemec GBE and Matusiak Ł. Analgesics: Nassif A, Ioannidis D, Podda M and Tzellos T. Experimental therapies: Prignano F, Kirby B and Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Surgery: Podda M, Guillem P, Bechara FG, Grimstad Ø, Horváth B, Hunger RE and Kemény L. van der Zee HH. Combination treatments (medical/medical, medical/surgical): Guillem P, van der Zee HH and Bechara FG. Treatment of draining tunnels: Tzellos T, Bechara FG and Grimstad Ø. Wound care: Horváth B, Hunger RE, Ingram JR and Romanelli M. Lifestyle interventions: Ingram JR, Horváth B and Dolenc-Voljc M. Long-term treatment: Horváth B, Ioannidis D, Jemec GBE and Tzellos T. Maintenance treatment: Matusiak Ł, Ioannidis D, Bettoli V and Tzellos T. Treatment options in classical treatment-resistant HS: Ioannidis D, Zouboulis CC, Marzano AV and Tzellos T. Syndromic HS treatment, Treatment biomarkers: Marzano AV and Zouboulis CC. Multidisciplinary approach: Bettoli V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ and Guillem P. Therapeutic conclusions and algorithm: Zouboulis CC, Jemec GBE and Prens EP. Patients view: McGrath B, Raynal H, Villumsen B and Just E. C.C. Zouboulis takes overall responsibility for the integrity of the entire work, from inception to the published article. All authors have participated at the guidelines preparation and voting procedure, drafted and critically revising the article for important intellectual content and finally approved the version to be published.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS