Darier disease: Current insights and challenges in pathogenesis and management

Linked article: S. Labbouz et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:883–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20641.

Abstract

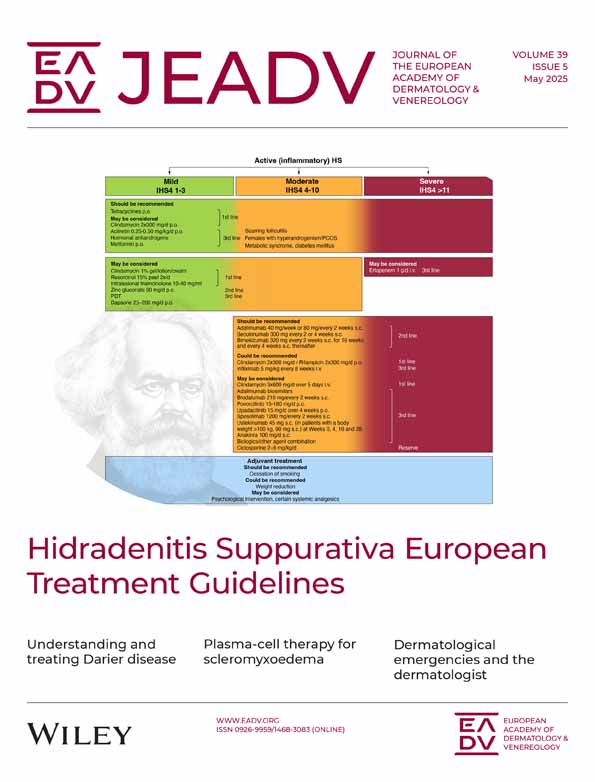

Darier disease is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis caused by mutations in the ATP2A2 gene encoding for sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase isoform 2. The skin disease is characterized by a chronic relapsing course with recurrent reddish-brown keratotic papules and plaques located mainly in seborrhoeic areas. Due to chronic inflammation and epidermal barrier defects of the skin, patients often develop severe bacterial and viral superinfections. Therapeutic options are limited, mainly symptomatic and in most cases unsatisfactory in the long term. Patients are advised to avoid aggravating factors such as high temperature, high humidity, UV radiation and mechanical irritation. To prevent superinfection, antiseptics and periodic use of topical corticosteroids are fundamental in treatment. In case of bacterial and viral superinfection, systemic anti-infective therapy is often necessary. Currently, the most effective treatment option for extensive and persistent skin lesions is systemic retinoids, which are thought to mainly target the epidermal compartment (e.g. by reducing hyperkeratosis). One hallmark of Darier disease patients is chronic skin inflammation. We and others have previously reported Th17 cells in the dermal infiltrate of inflamed Darier disease skin. Counteracting inflammation by blocking the IL-23/IL-17 axis improved skin manifestations in a small cohort of previously therapy-resistant patients over 1 year. Furthermore, several other topical treatment options for mild disease as well as various ablative therapies and surgical excision have been proposed to be effective in some patients with hypertrophic skin lesions. This article aims to outline the pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis/differential diagnosis and available treatment modalities of Darier disease.

Graphical Abstract

Darier disease (DD) is characterized by the following: Disrupted Ca2+ gradients, impaired desmosomes, impaired keratinocyte differentiation, type 17 inflammation, DC and LC ↓, Th17 cells ↑. DD treatment: First line: keratinocyte focused and/or anti-inflammatory. Second line: experimental approaches like specific targeting of the inflammatory infiltrate.

Why was the study undertaken?

- Although Darier disease (DD) has traditionally been considered primarily a keratinocyte-centred disorder, this review aims to highlight the role of the inflammatory dermal infiltrate.

What does this study add?

- We summarize a broad range of treatment options for patients with DD, including a new approach to specifically target the inflammatory Th17 infiltrate by administering IL-23A/IL-17A monoclonal antibodies (biologicals).

What are the implications of this study for disease understanding and/or clinical care?

- We aim to encourage clinicians to consider biologics targeting Th17 cells, which have minimal side effects, as a possible treatment option for patients with severe and recalcitrant disease.

INTRODUCTION

Darier disease (DD, dyskeratosis follicularis, Darier-White disease, OMIM: #124200, Orphanet: ORPHA: 218) is a rare autosomal dominant inherited skin condition which presents with hyperkeratotic greasy papules and plaques predominantly in the seborrhoeic areas, typically beginning after puberty.1, 2 Extracutaneous symptoms may include nail abnormalities, oral and genital mucosal involvement, ophthalmic complications and neuropsychiatric/neurodegenerative illness.2-5 The earliest signs of disease often begin on the hands and nails.1, 2 The disease follows a chronic course with acute exacerbations (trigger factors: excess heat/sweating, UVB, humidity, friction, mental distress and febrile illness) and an increased risk of bacterial and viral superinfections, which can further trigger or worsen the illness.2 The patients' quality of life is significantly diminished due to symptoms such as itching, burning sensations, pain and body odour.1, 6 Cases of DD have been reported all over the world, with a prevalence ranging from 1:100,000 to 1:30,000 in northern European populations.3, 4, 7 Both men and women are affected with equal frequency.3 Complete penetrance is observed in adults, although there is variability in phenotypic expression, with some patients presenting exclusively with nail changes.8, 9

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

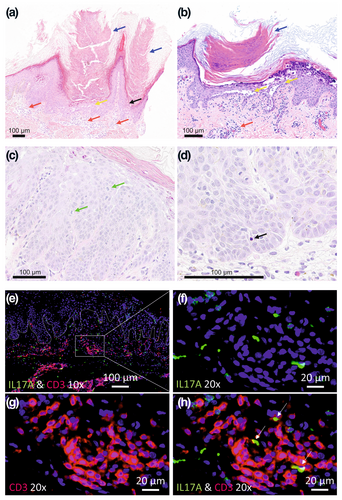

DD is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, with mutations in the ATP2A2 gene encoding the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA2) protein identified as the underlying genetic defect. SERCA2 is a Ca2+ pump, located in the endoplasmic reticulum and plays a crucial role in calcium homeostasis in keratinocytes, as these cells do not express the SERCA isoform SERCA3. Mutations in SERCA2 are believed to vastly manifest in keratinocytes, leading to dysregulated intracellular calcium signalling, impaired cell–cell adhesion and dyskeratosis.10 These mechanisms contribute to the characteristic skin manifestations of DD. Research into the pathophysiology of DD has predominantly focused on the epidermis, with particular emphasis on keratinocytes. In a recent study, Zaver et al. observed heightened MAPK signalling in an organotypic in vitro model of DD using human keratinocytes lacking SERCA2, suggesting MEK inhibition as a potential treatment avenue.11 Although chronic skin inflammation is a hallmark of DD skin, which significantly affects patients' well-being, knowledge of the involvement of the immune system in DD's pathogenesis and progression is limited. The inflammatory immune infiltrate of the affected skin of patients with DD primarily consists of CD4+ T lymphocytes, with few CD8+ T cells and occasional CD20+ B cells being found.12 Interestingly, it has been shown that epidermal and dermal dendritic cells and Langerhans cells are decreased in DD.12 Transcriptomic analyses of lesional versus unlesional skin of patients with DD (bulk RNAseq) revealed significant upregulation of pathways related to epidermal repair, inflammation and immune defence. These findings reflect the activation of epithelial and immune response mechanisms in reply to the dysbiotic microbiome in DD.13 No apparent changes in the immune cell composition of peripheral blood of patients with DD were observed.14 Previously, skin inflammation in patients with DD was primarily attributed to impaired epidermal barrier function or dysbiosis of the cutaneous microbiome. However, a recent report by Chen et al. directly linked mutations in the ATP2A2 gene to compromised immune function, particularly affecting the B-cell compartment.15 They demonstrated that SERCA2 is crucial for V(D)J recombination and subsequent B-cell maturation, potentially explaining reduced mature B-cell counts in some patients with DD. In addition, several recent studies report an increased expression of IL-17-signalling-related cytokines in the lesional skin of patients with DD.13, 16, 17 Consistent with this, in our study, we found an increased presence of tissue-resident Th17 cells in both the circulation and skin of patients with DD, comparable to levels seen in psoriasis (Figure 1e–h).17

CLINICAL FEATURES AND COMORBIDITIES

DD typically manifests during adolescence or early adulthood, with varying clinical presentation, ranging from mild to severe forms.1, 2 Patients with severe disease experience an earlier onset than those with mild disease.2 Clinically, DD is characterized by discrete or confluent greasy skin-coloured or reddish-brown papules and plaques with a keratotic surface.1, 2 Commonly affected areas include seborrhoeic areas of the trunk, face, scalp margins, temples, ears, scalp, neck, and intertriginous areas such as the axillary and inguinal folds and, in women, the submammary region. Recently, a study including 76 patients from 34 families investigated clinical symptoms of DD and identified ‘classical’ versus ‘non-classical’ lesions of DD disease. Classical lesions were defined as the most common, disease-characterizing, and include keratotic papules, pits and wart-like lesions on the skin (Figure 2a–e) and mucosa (Figure 2f) as well as nail abnormalities (Figure 2g,h). Non-classical DD lesions include acral keratoderma, leucodermic macules, giant comedones, keloid-like vegetations (Figure 2i–k) and acral haemorrhagic blisters (Figure 2l), and are rarer, appearing only in a subgroup of patients.2 In this study, all patients (100%) exhibited at least one of the classical DD lesions, while 33% presented with non-classical lesions.2 On the trunk, the lesions may merge into larger lesions (Figure 2j), while in intertriginous areas, they may form macerated hypertrophic growths. In general, the hands and fingernails have been identified as the most common sites for lesions, offering a highly sensitive method to assist in diagnosing the disease (please see below).2 Palmoplantar manifestations often feature palmar papules with central depression known as pits, along with yellowish-brown hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 2d).1, 2 Additionally, flat, wart-like papules on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet may appear independently (Figure 2e). This condition is referred to as acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, which is an allelic variant of DD.18, 19 The wart-like lesions on the hands become more noticeable after soaking in water for 5 min, a phenomenon known as the wet hand sign.2 In some patients, the primary manifestation of the condition may be the presence of confluent hyperkeratotic plaques on the limbs (Figure 2k).20

Classical nail lesions include longitudinal erythronychia and leukonychia (longitudinal red and white lines), ridging and splitting (Figure 2g) as well as V-shaped notches at free edges of the nails (Figure 2h), and subungual hyperkeratosis.2, 21 Rarely, complete nail dystrophy occurs.22

Oral mucosal involvement (hard palate and buccal mucosa) frequently shows ‘cobblestone-like’ papules and leukokeratosis (Figure 2f).23 The oral mucous membranes may show gingival hyperplasia and macroglossia.24 Patients with severe DD are more likely to have oral involvement compared to those with mild disease.2 Besides, the mucosa might be involved as well, indicated by pink papules with central erosions, especially in patients with severe disease.2 Moreover, DD skin lesions can also appear on eyelids,25 whereas keratotic precipitates can appear on the endothelium of the eye.26 Further ophthalmic complications may also arise, such as recurrent herpes keratitis, minor corneal epithelial ulcerations, conjunctival keratosis, blepharitis or conjunctival hyperaemia and opacities in the periphery of the cornea.1, 25, 27, 28

Individuals with DD often experience itching, burning sensations and pain. Particularly when intertriginous areas are involved, they may emit an unpleasant, musty body odour, contributing to social isolation.1, 6

Several variants of DD that are associated with non-classical DD skin manifestations have been reported.2 In the bullous variant of the disease, vesicles and blisters often develop due to sweating, stress and fever (illness), showing intraepidermal fissures upon histological examination.29-31 The haemorrhagic form is characterized by superficial haemorrhages in acral areas, induced by mechanical stress (Figure 2l).2, 32-34 Occasionally, a variant of DD with prominent comedones emerges, primarily affecting the face, often without other signs.2, 35, 36 In individuals with pigmented skin, focal lesions can also lead to guttate leucoderma, characterized by confetti-like hypopigmented macules and papules.2, 37

In linear/segmental DD, lesions are situated along Blaschko's lines, reflecting genetic mosaicism-most frequently Type 1 segmental mosaicism. This is characterized by heterozygosity for a post-zygotic de novo mutation and resembles epidermal nevi.38, 39 However, Type 2 segmental mosaicism, involving homozygosity or hemizygosity within the segment alongside heterozygosity outside the segment, has also been reported.39

Impetiginization (Figure 2i) and eczematization are frequently observed, and patients show increased susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections, particularly Staphylococcus aureus and herpes simplex virus.40 The presence of S. aureus colonization in the skin and nasal passages is a trigger for exacerbations, and its elimination as a treatment goal is a crucial element in managing these patients (please also see below).13, 41, 42 Some medications have been shown to exacerbate DD (diltiazem, lithium carbonate, IFNα2a) as well as COVID-19 vaccinations and COVID-19 infections.43-47

DD is considered a multi-organ condition, which is not surprising given the importance of SERCA2 in physiology and pathophysiology (possible associations with Type I diabetes, heart failure and neuropsychiatric disorders).4 Neuropsychiatric disorders such as mental retardation, depression, bipolar disorder, suicidal ideation, psychosis and epilepsy are more prevalent in individuals with DD than in the general population.5, 48-50 Furthermore, neurodegenerative disorders as specifically as Parkinson's disease and vascular dementia have been shown to be associated with DD, emphasizing the importance of raising awareness, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and conducting further research to uncover the underlying mechanisms.5 Above all, DD and learning disabilities seem to be related.51

CLASSIFICATION OF SEVERITY

The severity of DD is very heterogeneous between individuals. It is therefore important to objectively assess the severity of the disease. As with most rare diseases, there is no validated scoring method for DD, but recently, a score has been proposed by Amar et al., which was specifically tailored to DD (adapted SCORAD score which includes the hyperkeratosis and erosions, as well as subjective itch and pain scores).13 This is the first published severity score, which is proving to be highly valuable and crucial in guiding treatment decisions and assessing and documenting treatment success. However, this clinical score does not include any aspect of the multi-organ disease.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis can often be made based on clinical presentation (classical lesions vs. non-classical lesions).2 Subtle lesions on the hands and characteristic findings on the nails aid in diagnosing DD.2 However, confirmation by histological examination is essential. Histologically, the lesions exhibit suprabasal clefts in the epithelium, accompanied by acantholysis and the presence of dyskeratotic cells known as ‘corps ronds’ and ‘corps grains’ (Figure 1a–d).52 ‘Corps ronds’ are larger structures typically found in the granular layer and contain irregular eccentric, and sometimes pyknotic, nuclei. Grover's disease shares histological patterns with DD, making it difficult to distinguish the two histologically.53 However, the diseases can be easily distinguished clinically, as the onset of Grover's disease is later in life and the lesions usually resolve after several weeks or months.53 Even when clinical findings and histopathology are consistent, a molecular genetic examination and genetic counselling is advised in all patients (ATP2A2 mutation screening), for example, before planning pregnancy, as there is a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. Prenatal diagnostic tests and procedures are available for couples affected by the identified genetic variant. Importantly, in a significant minority of patients we do not find typical mutations.4

Due to the rarity of the condition, the disease is often recognized very late. Several differential diagnoses must be considered and complicate the process of diagnosing DD. The most common differential diagnoses are Hailey–Hailey disease, seborrhoeic dermatitis, Grover's disease, pemphigus vegetans and, very rarely, Dowling-Degos disease/Galli Galli disease (Table 1).54 Furthermore, simple warts must also be considered as a differential diagnosis for palmar lesions of DD. A common differential diagnosis for linear DD is ILVEN (inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus).55

| Differential diagnosis | Main characteristics | Distinctive feature |

|---|---|---|

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis | Very common, papulosquamous disease mainly in seborrhoeic areas (scalp, face, trunk), most prevalent in infancy and middle age, minimal itch | Anamnesis and clinical presentation |

| Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis) | Common, self-limiting acquired acantholytic dermatosis, very itchy papulovesicular rash on the trunk, mostly Caucasian men in fifth decade, common in winter | Anamnesis and clinical presentation |

|

Hailey-Hailey disease (familial benign pemphigus) Orphanet:2841 |

Rare symmetrical erosive, bullous or hypertrophic lesions in the intertriginous areas, painful, mostly in third/fourth decade | ATP2C1 mutation (autosomal dominant) |

|

Pemphigus vegetans Orphanet:79479 |

Rare mucocutaneous bullae with subsequent erosion and formation of vegetative plaques, predominantly affecting intertriginous areas and the oral mucosa |

Autoimmune disease Antibodies against desmoglein 1 and 3 (DIF) |

|

Dowling-Degos Disease Orphanet:79145 |

Very rare reticular reddish-brown to dark-brown, macular and/or comedone-like, hyperkeratotic papules with hypopigmented macules, predominantly affecting flexures; mostly fourth to sixth decade | KRT5 mutation (autosomal dominant) |

MANAGEMENT

Treatment of genodermatoses in general is very challenging.56 DD as multisystemic disease is particularly demanding, requiring a multidisciplinary management. The primary goal in treating patients is to first identify the various aspects of the disease—cutaneous, mucosal and extracutaneous—to evaluate its impact on the patient's quality of life and daily functioning. Treatment focuses on reducing exacerbations by managing triggers, minimizing Staphylococcus colonization in the skin and nasal passages, and administering appropriate medical therapy both for chronic management and during flare-ups.

While some lesions fluctuate with environmental factors, others are more severe and show limited response to treatment. Evaluating treatment response by distinguishing between persistent and transient lesions is important, as persistent DD lesions were linked to the presence of second-hit somatic variants in the ATP2A2 gene. The discovery of these variants provides important insights into the mechanisms driving the chronic nature of persistent DD lesions.57

Because of the limited number of patients, there have not been any randomized placebo-controlled trials, and individual reports of successful treatments may not accurately reflect the overall picture. There are a limited number of effective treatments for DD, and to date all therapeutic options have been purely symptomatic. We summarize the current treatment options in Table 2.

| Management treatment ladder | Ref. |

|---|---|

| General recommendations | |

| Identifying cutaneous, mucosal and extracutaneous aspects: corresponding multidisciplinary management of comorbidities (neuropsychiatric, neurodegenerative, etc.) | [2-5] |

| Avoidance of trigger factors (excess heat/sweating, UVB, humidity, friction, mental distress, febrile illness, superinfections) | [2] |

| First line (common recommendations) | |

| Emollients (with urea, glycerine) and topical antiseptics (with octenidine or chlorhexidine) | [58] |

| Topical antibiotics and antifungals | [58] |

| Topical corticosteroids class II–III (temporarily), class IV (short term), in intertriginous areas topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) | [58-60] |

| Exacerbations: oral antibiotics, oral antivirals, e.g. acyclovir | [13, 40, 61] |

| Chronic disease: oral acitretin 0.25–0.5 mg/kg/day or isotretinoin 0.5 mg/kg/day (extensive and persistent lesions), oral alitretinoin (women with childbearing potential) | [62, 63] |

| Second line (experimental approaches) | |

| Topical medication (all for limited disease): topical retinoids, topical vitamin D3 analogues (calcipotriol, tacalcitol), 5-fluorouracil cream, diclofenac gel 3%, topical agent containing vitamin A (retinyl palmitate), vitamin E and urea | [68-76] |

| Botulinum toxin (limited intertriginous disease) | [77] |

| Ablative therapies: dermabrasion, CO2 laser, Er:YAG laser, pulse dye laser, diode laser, photodynamic therapy (limited hypertrophic disease) | [78, 79] |

| Large-scale surgical excision, use of allograft skin (limited hypertrophic disease) | [80, 81] |

| Oral naltrexone (mild to moderate disease) | [85] |

| Oral doxycycline, oral vitamin A (mild to moderate disease) | [87-89] |

| Oral magnesium chloride-calcium carbonate (severe disease) | [90] |

| Intravenous low-dose immunglobulines (severe disease) | [92] |

| Oral baricitinib (JAK inhibitor, severe disease) | [93] |

| Oral apremilast (phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, severe disease) | [94, 95] |

| Systemic therapy specifically targeting inflammation (biologicals) | |

| Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-17A/IL-23A (i.m. secukinumab, guselkumab, severe disease and treatment-refractory patients) | [17] |

| Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-4/IL-13 (i.m. dupilumab, tralokinumab, severe disease and treatment-refractory patients) | [96] |

Basic recommendations include hygiene measures to prevent secondary infection, and the avoidance of excessive heat, humidity, friction and sun exposure.

First line (common recommendations)

For mild cases of DD, topical therapies such as emollients containing urea or glycerine to reduce hyperkeratosis are recommended.58 Topical antiseptics like chlorhexidine or octenidine, as well as topical antibiotics and antifungals, may be used to prevent or treat secondary infections.58 In the acute phase of skin inflammation, topical corticosteroids are usually used for treatment, with moderate to highly potent steroids often required.58 Of note, chronic use of potent topical corticosteroids should be avoided, especially in skin folds. Instead, calcineurin inhibitors are recommended for long-term management.59, 60 In cases of infectious exacerbations, typically caused by staphylococcal infections, a short course of appropriate oral antibiotics may be required.13 There are no established guidelines on the use of long-term oral antibiotics. Herpes simplex infection complicating DD requires urgent treatment with oral or parenteral antiviral agents such as acyclovir.40, 61

For chronic disease management of severe or refractory disease, oral retinoids, including acitretin and isotretinoin, are considered the primary treatment.62, 63 However, as their long-term use necessitates careful monitoring due to potential side effects (dry lips, cheilitis, scaling, skin atrophy and fragility, hepatotoxicity, ophthalmological complications, pancreatitis and skeletal changes), intermittent use could be considered.64, 65 Acitretin at a dosage of 0.25–0.5 mg/kg/day or isotretinoin at a dosage of 0.5 mg/kg/day can effectively reduce hyperkeratosis and malodour. Oral alitretinoin (another retinoid) may serve as an alternative to acitretin and could be particularly useful in women of childbearing age.66, 67

Second line (experimental approaches)

Other therapeutic modalities, such as topical retinoids or topical calcipotriol/tacalcitol, have been shown to be effective for the skin symptoms of DD, although some patients may experience irritation.68-71 Furthermore, topical use of 5-fluorouracil cream, as well as topical use of diclofenac gel 3% and a topical agent containing vitamin A (retinyl palmitate), vitamin E and urea have been shown to be effective in some case reports.72-76 Botulinum toxin injections appear to be another effective treatment for patients with intertriginous Hailey–Hailey disease or DD.77 Furthermore, ablative therapies such as dermabrasion, CO2 laser or Er:YAG, pulse dye laser or diode laser may be considered in selected cases, as well as large-scale surgical excisions in limited cases or the use of allograft skin for selected extensive eroded skin areas.78-81 In addition, successful treatment with conventional photodynamic therapy (PDT), daylight PDT for facial disease and ALA-PDT combined with 2940 nm ablative fractional Er:YAG laser have been shown to be effective in some patients.82-84

In a small case series of six patients with DD, the opioid antagonist naltrexone was shown to be beneficial in two patients with mild to moderate DD, while the response varied vastly in the overall patient cohort.85 However, naltrexone is more effective in HHD, although the mechanism of its action in acantholytic skin disease is unknown.86 Moreover, single case reports have shown that doxycycline monotherapy, oral magnesium and oral vitamin A could be treatment options for individual patients with DD with severe phenotypes.87-89 Oral magnesium chloride-calcium carbonate was successfully used in a pregnant patient with severe DD.90 Further case reports showed a combination of naltrexone and isotretinoin, treatment with intravenous low-dose immunglobulins in a patient with recalcitrant disease, and one patient responded successfully to oral treatment with the JAK inhibitor baricitinib.91-93 Moreover, some case reports reported successful treatment with apremilast (a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor).94, 95 However, data on the long-term effectiveness of these therapies are lacking.

Treatment options that specifically target inflammation (biologics)

In therapy-refractory patients with very extensive skin involvement, a systemic therapy approach targeting the IL-23/IL-17 axis using monoclonal antibodies may be an option. We previously reported a personalized medicine approach for patients with DD. We found increased IL17A/IL23A in the lesional skin of these patients along with increased numbers of Th17 cells. In three of those patients, administration of an anti-IL23A (guselkumab) or anti-IL17A (secukinumab) treatment led to an amelioration of skin manifestations along with reductions in pruritus, malodour and secondary infections over 1 year.17 Whether the IL-17-skewed immunophenotype is a primary effect of the disease or a secondary result due to microbial colonization is not yet clear. Furthermore, the exact role of the Th17 cells in DD has to be elucidated. Above all, successful use of type 2 inflammation inhibitors (targeting IL-4/IL-13, dupilumab and tralokinumab) in two patients with severe and recalcitrant DD has been reported.96 These findings are in line with other reports showing that specific targeting of the inflammation in inherited skin diseases, which are thought to be primarily driven by a defect epidermal barrier function, is effective.97-100 Thus, the mechanism of action of using biologicals/targeting the overexpressed cytokine is very different to the use of retinoids. However, no general treatment recommendations can be made from those case reports, and the risk of using immunosuppressive drugs (such as biologics) in patients with DD, who have an elevated risk of infection, must be considered. Multiple safety studies in mainly patients with psoriasis treated with guselkumab and secukinumab exist, highlighting the increased risk of respiratory tract infections, candidiasis and inflammatory bowel disease after treatment with secukinumab.101-103 So far, only one case of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome associated with an IL-17 inhibitor has been reported.104 To our knowledge, no reports of sepsis-related fatalities in DD or psoriasis have been documented so far.105

CONCLUSION

DD is a challenging dermatological condition characterized by a spectrum of clinical manifestations and genetic heterogeneity. Advances in our understanding of its pathophysiology have paved the way for targeted therapeutic approaches, although further research is needed to elucidate the optimal management strategies and improve patient outcomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ME, SK and WH conceptualized the manuscript. ME wrote the original draft of the manuscript. ME, ID, JT, SA and PN curated the data and images for the manuscript. ME and SK were responsible for the visualization of the manuscript. SK, SA, JDW, EG and WH reviewed and edited the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr Antonia Currie for proofreading the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was obtained for this review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Johannes Kepler University Linz (EK No. 1327/2021).

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.