Healthcare resource utilization and healthcare costs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors vs dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in Japan: A real-world administrative database analysis

ABSTRACT

Aims/Introduction

Healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and healthcare costs are important factors to consider when selecting appropriate treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus. We compared the HCRU and healthcare costs of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) vs dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan.

Materials and Methods

This was a Japanese retrospective cohort study conducted using the JMDC Claims Database (January 1, 2015–December 31, 2021). Patients newly treated with an SGLT2i (31,872 patients) or a DPP4i (73,279 patients) were matched 1:1, using propensity score, after excluding patients without continuous SGLT2i or DPP4i prescriptions after the index date. HCRU and healthcare costs were compared between the treatment groups in the full cohort and subcohorts/subgroups of different baseline characteristics, including body mass index (BMI).

Results

After matching, patient characteristics were well balanced (17,767 patients each). Patients receiving an SGLT2i vs those receiving a DPP4i had significantly lower numbers of hospitalizations per person per month (PPPM) and outpatient visits PPPM, and had shorter lengths of stay per hospitalization. Healthcare costs, including all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM and all-cause hospitalization costs PPPM, were generally lower in patients receiving an SGLT2i than those receiving a DPP4i. Similar results were observed among patients with a higher BMI but not among patients with a lower BMI.

Conclusions

SGLT2i were associated with lower HCRU and healthcare costs than DPP4i, suggesting economic benefits with SGLT2i vs DPP4i in type 2 diabetes mellitus management.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in treatment and prevention efforts, the economic burden in patients with diabetes mellitus remains high, both globally and in Japan1-4. The total costs of diabetes were 1.3 trillion US dollars (USD) in 2015 and are expected to increase to 2.1 trillion USD by 20301. In 2020, the total medical costs of diabetes accounted for 3.8% of Japan's total medical expenditure5. These costs are largely attributed to the treatment of diabetes-related comorbidities and complications4, 6, including macrovascular (cardiovascular diseases [CVD]) and microvascular diseases (diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy)7, 8, with the treatment of diabetic complications accounting for ~50% of age/gender-weighted lifetime medical costs4.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are associated with various clinical benefits, including reduced cardiometabolic risks, risks of CVD events, hospitalization for heart failure, and progression of renal disease vs other glucose-lowering drugs (oGLDs) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus9-13. The Japan Diabetes Society recommends selecting type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment based on patient characteristics and medication costs14. However, there are limited data to suggest that physicians select treatments based on cost-effectiveness. Previous studies have suggested that SGLT2i are more cost-effective than oGLDs in treating type 2 diabetes mellitus15-18, but data on the economic benefits of oGLDs, including SGLT2i, are limited in Japan. Therefore, an improved understanding of healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and the healthcare costs of SGLT2i may help physicians to select appropriate treatments and to reduce the economic burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

This retrospective cohort study, using a large administrative database, aimed to compare HCRU and healthcare costs in patients newly treated with SGLT2i (either alone or in combination with oGLDs) vs those newly treated with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i; either alone or in combination with oGLDs) in Japan. The HCRU and healthcare costs associated with SGLT2i vs DPP4i were also assessed among patient groups with various clinical characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted in Japan (January 1, 2015–December 31, 2021) using data from the JMDC Claims Database (JMDC Inc., Tokyo, Japan; Figure S1) provided by health insurance associations in Japan. The database contains inpatient, outpatient, dispensing claims and annual health check-up data collected from medical institutions, including Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) hospitals and non-DPC hospitals (DPC hospitals participate in a case-mix patient classification system linked with a lump-sum system for inpatients in acute care hospitals)19. As of February 2022, the database contains ~14 million cumulative patient data20. The protocol was approved by Medical Affairs Japan – Protocol Review Committee (protocol number: 1941-MA-1631), and the study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all relevant regulations and guidelines for clinical study conduct. The study used retrospective, de-identified data; institutional ethics review or informed consent was not required.

Study population

Patients were included in this study if they had ≥1 prescription claim for either an SGLT2i or a DPP4i (i.e., index treatment) between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2021 (see Table S1 for index treatment codes) and a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10]: E11.x) or unspecified diabetes mellitus (ICD-10: E14.x) on or prior to the index date (defined as the date of the first recorded receipt of the index treatment). Patients were excluded if they were: aged <18 years at index date; had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (ICD-10: E10.x) on or prior to the index date; had a diagnosis of gestational diabetes (ICD-10: O24.x) in the baseline period (defined as index date plus the period from 1 year prior to the index date); had a prescription record for an SGLT2i and/or a DPP4i or an SGLT2i/DPP4i fixed-dose combination in the baseline period, other than the index treatment on the index date; or had <1 year of database records on or prior to the index date.

Outcome measures

The HCRU and healthcare costs during the follow-up period (defined as the period with continuous prescription of an index treatment within 1 year after the index date) were compared between the treatment groups. The HCRU endpoints included: number of hospitalizations per person per month (PPPM; defined as total number of hospitalizations after the index date divided by the follow-up period [number of months] for each patient); length of stay per hospitalization per person (defined as the average number of days of hospitalization for each patient, calculated as the total days of hospitalization after the index date divided by the number of hospitalizations after the index date for each patient, with those who were not hospitalized being assigned 0 days of hospitalization); length of stay per hospitalization (defined as the average number of days in each hospitalization for all hospitalized patients, calculated as the total days of hospitalization divided by the number of hospitalizations after the index date for each hospitalized patient, with those not hospitalized being excluded from the calculation); proportion of DPC and non-DPC hospitalizations; number of outpatient visits PPPM (defined as total number of outpatient visits after the index date divided by the follow-up period for each patient); and treatment persistence from the index date. Healthcare cost endpoints included: all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM; all-cause hospitalization costs PPPM; all-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM; and all-cause pharmacy costs PPPM, where ‘all-cause’ healthcare costs were defined as any healthcare costs, including non-type 2 diabetes mellitus-related healthcare costs. Secondary endpoints included HCRU and healthcare costs in subcohorts, stratified by body mass index (BMI) (non-obese [<25 kg/m2] vs pre-obese [25 to <30 kg/m2] vs obese [≥30 kg/m2] based on the World Health Organization [WHO] classification21), and the presence of vascular complications (no vascular disease vs macrovascular disease vs microvascular disease) at baseline, and by baseline number of oGLDs subgroup. Post hoc endpoints were HCRU and healthcare costs by quartile subgroups by all-cause overall healthcare cost during follow-up, and in patients without hospitalization during follow-up, and percentile distribution of all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All patients meeting the eligibility criteria were included. Patients were matched 1:1 using propensity score matching after excluding patients who did not have continuous prescriptions of index treatments after the index date (i.e., early dropout patients) for the full cohort and subcohorts. The propensity score was calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model consisting of covariates that may predict SGLT2i treatment; covariates were patient demographics, relevant medical history and medication use, baseline HCRU and healthcare costs, and index year. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to assess the degree of balance between the treatment groups; covariate imbalance was defined as a SMD of >0.1. Before and after matching, baseline characteristics including HCRU and healthcare costs were descriptively summarized by treatment groups in the full cohort (crude and matched patients) and in the subcohorts (crude and matched patients).

Treatment persistence from index date was defined as the time from index date to treatment discontinuation, estimated using a grace period of 60 days for each treatment group. Patients were considered to have continued treatment if the difference between the previous prescription date plus days’ supply of the drug was ≤60 days. Patients were considered to have discontinued treatment if the difference between the previous prescription date plus days’ supply of the drug and the current prescription date was ≥61 days, or if patients switched to or added on the comparator drug.

The difference in HCRU and healthcare costs between the treatment groups was defined as the HCRU or healthcare costs of SGLT2i minus those of DPP4i. Least squares mean (LSM) difference and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values were calculated using t-tests for endpoints of ‘per hospitalization’ and paired t-tests for all other endpoints; a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The HCRU and healthcare costs were analyzed in the full matched cohort, in the matched subcohorts, and by matched subgroups. Healthcare costs were collected and calculated as Japanese Yen and converted to USD (exchange rate $1.00 = ¥115.17, December 30, 2021). See Tables S2–S4 for medical history (i.e., adapted Diabetes Complication Severity Index and Charlson Comorbidity Index) and medication use codes. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Study population

Of the 105,151 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus identified from the database who met the eligibility criteria, 31,872 and 73,279 patients were newly treated with an SGLT2i and a DPP4i, respectively (Figure S2). Before propensity score matching and after excluding early dropout patients (SGLT2i: 3,935 patients, DPP4i: 7,388 patients), 93,828 patients (SGLT2i: 27,937 patients; DPP4i: 65,891 patients) were included in the crude population. After propensity score matching, 17,767 patients in each of the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups were included.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

Before matching, the SGLT2i group was younger and had a higher mean BMI than the DPP4i group (Table 1). A greater proportion of patients in the SGLT2i group had microvascular disease only and both macrovascular and microvascular disease and used biguanides, thiazolidinediones, insulins, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists vs those in the DPP4i group. Conversely, the DPP4i group had higher hemoglobin A1c and had a greater proportion of treatment-naïve patients. After matching, all baseline characteristics were well balanced and similar across the treatment groups (SMD <0.1) (Table 1). See Tables S5 and S6 for patient demographics and clinical characteristics by subcohorts.

| Variable | Before matching | After matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i (n = 27,937) | DPP4i (n = 65,891) | SMD | SGLT2i (n = 17,767) | DPP4i (n = 17,767) | SMD | |

| Sex†, male, n (%) | 20,465 (73.3) | 47,941 (72.8) | 0.01 | 14,415 (81.1) | 14,386 (81.0) | 0.00 |

| Age†, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 50.9 (9.7) | 54.0 (9.7) | −0.31 | 51.5 (8.4) | 51.5 (8.8) | 0.00 |

| Median (IQR) | 52.0 (45.0, 58.0) | 54.0 (48.0, 61.0) | 52.0 (46.0, 57.0) | 52.0 (46.0, 58.0) | ||

| Index year†, n (%) | ||||||

| 2015 | 940 (3.4) | 6,137 (9.3) | 0.25 | 547 (3.1) | 483 (2.7) | 0.00 |

| 2016 | 1,745 (6.2) | 7,269 (11.0) | 1,061 (6.0) | 978 (5.5) | ||

| 2017 | 2,670 (9.6) | 8,922 (13.5) | 1,708 (9.6) | 1,670 (9.4) | ||

| 2018 | 4,085 (14.6) | 10,335 (15.7) | 2,676 (15.1) | 2,677 (15.1) | ||

| 2019 | 5,175 (18.5) | 10,907 (16.6) | 3,365 (18.9) | 3,436 (19.3) | ||

| 2020 | 5,856 (21.0) | 11,333 (17.2) | 3,730 (21.0) | 3,809 (21.4) | ||

| 2021 | 7,466 (26.7) | 10,988 (16.7) | 4,680 (26.3) | 4,714 (26.5) | ||

| Drinking habit†, n (%) | ||||||

| Everyday | 3,709 (13.3) | 10,787 (16.4) | −0.09 | 3,360 (18.9) | 3,338 (18.8) | 0.00 |

| Sometimes | 6,599 (23.6) | 14,143 (21.5) | 5,735 (32.3) | 5,704 (32.1) | ||

| Rarely | 8,881 (31.8) | 19,222 (29.2) | 7,497 (42.2) | 7,529 (42.4) | ||

| Missing | 8,748 (31.3) | 21,739 (33.0) | 1,175 (6.6) | 1,196 (6.7) | ||

| Smoking history†, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 6,254 (22.4) | 16,203 (24.6) | −0.05 | 5,489 (30.9) | 5,494 (30.9) | 0.00 |

| Missing | 7,720 (27.6) | 19,251 (29.2) | 398 (2.2) | 408 (2.3) | ||

| BMI†, kg/m2 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 29.63 (5.19) | 26.89 (4.69) | 0.55 | 29.12 (4.66) | 29.14 (5.12) | 0.00 |

| Median (IQR) | 28.90 (26.00, 32.50) | 26.20 (23.70, 29.40) | 28.60 (25.80, 31.90) | 32.10 (25.50, 32.10) | ||

| BMI group, kg/m2, n (%) | ||||||

| Non-obese (<25) | 3,522 (12.6) | 17,891 (27.2) | 3,176 (17.9) | 3,676 (20.7) | ||

| Pre-obese (25 to <30) | 8,470 (30.3) | 19,257 (29.2) | 7,680 (43.2) | 7,199 (40.5) | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 8,701 (31.1) | 10,538 (16.0) | 6,911 (38.9) | 6,892 (38.8) | ||

| Missing | 7,244 (25.9) | 18,205 (27.6) | ||||

| HbA1c†, % | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.52 (1.62) | 7.81 (1.72) | −0.18 | 7.54 (1.63) | 7.55 (1.43) | −0.01 |

| Median (IQR) | 7.10 (6.50, 8.00) | 7.30 (6.70, 8.30) | 7.10 (6.50, 8.00) | 7.20 (6.60, 8.00) | ||

| Vascular complications†, n (%) | ||||||

| Macrovascular disease (including both macro- and microvascular disease) | 7,384 (26.4) | 14,522 (22.0) | 0.12 | 4,339 (24.4) | 4,220 (23.8) | 0.01 |

| Microvascular disease only | 5,397 (19.3) | 11,674 (17.7) | 3,252 (18.3) | 3,262 (18.4) | ||

| No vascular disease | 15,156 (54.3) | 39,695 (60.2) | 10,176 (57.3) | 10,285 (57.9) | ||

| Vascular complications, n (%) | ||||||

| Both macro- and microvascular disease | 2,574 (9.2) | 4,888 (7.4) | 1,402 (7.9) | 1,369 (7.7) | ||

| Macrovascular disease only | 4,810 (17.2) | 9,634 (14.6) | 2,937 (16.5) | 2,851 (16.0) | ||

| Microvascular disease only | 5,397 (19.3) | 11,674 (17.7) | 3,252 (18.3) | 3,262 (18.4) | ||

| No vascular disease | 15,156 (54.3) | 39,695 (60.2) | 10,176 (57.3) | 10,285 (57.9) | ||

| CCI† | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.4) | 0.10 | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.4) | 0.01 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | ||

| aDCSI† | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.13 | 1.0 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.7) | 0.02 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | ||

| oGLD†, yes, n (%) | ||||||

| Sulfonylureas | 1,580 (5.7) | 4,147 (6.3) | −0.03 | 871 (4.9) | 885 (5.0) | 0.00 |

| Glinides | 536 (1.9) | 1,082 (1.6) | 0.02 | 300 (1.7) | 291 (1.6) | 0.00 |

| Biguanides | 7,573 (27.1) | 12,399 (18.8) | 0.20 | 4,463 (25.1) | 4,518 (25.4) | −0.01 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 1,229 (4.4) | 1,765 (2.7) | 0.09 | 647 (3.6) | 626 (3.5) | 0.01 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | 1,356 (4.9) | 3,464 (5.3) | −0.02 | 787 (4.4) | 750 (4.2) | 0.01 |

| Insulins | 2,255 (8.1) | 3,364 (5.1) | 0.12 | 978 (5.5) | 943 (5.3) | 0.01 |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | 1,085 (3.9) | 326 (0.5) | 0.23 | 235 (1.3) | 177 (1.0) | 0.03 |

| Imeglimin | 0 (0) | 2 (0.0) | −0.01 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | − |

| Number of oGLDs, n (%) | ||||||

| Naïve (0 oGLDs) | 17,950 (64.3) | 46,693 (70.9) | 11,967 (67.4) | 11,888 (66.9) | ||

| Monotherapy (1 oGLD) | 6,315 (22.6) | 13,546 (20.6) | 4,030 (22.7) | 4,168 (23.5) | ||

| Multitherapy (≥2 oGLDs) | 3,672 (13.1) | 5,652 (8.6) | 1,770 (10.0) | 1,711 (9.6) | ||

| Medication use†, n (%) | ||||||

| Lipid-lowering agents | 10,807 (38.7) | 21,108 (32.0) | 0.14 | 6,727 (37.9) | 6,790 (38.2) | −0.01 |

| P2Y12 inhibitors | 723 (2.6) | 1,331 (2.0) | 0.04 | 404 (2.3) | 385 (2.2) | 0.01 |

| Warfarin | 213 (0.8) | 395 (0.6) | 0.02 | 109 (0.6) | 110 (0.6) | 0.00 |

| Anticoagulants | 470 (1.7) | 747 (1.1) | 0.05 | 233 (1.3) | 222 (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Low-dose aspirin | 1,239 (4.4) | 2,506 (3.8) | 0.03 | 719 (4.0) | 689 (3.9) | 0.01 |

| Beta blockers | 2,967 (10.6) | 4,576 (6.9) | 0.13 | 1,660 (9.3) | 1,580 (8.9) | 0.02 |

| Alpha blockers | 448 (1.6) | 810 (1.2) | 0.03 | 256 (1.4) | 253 (1.4) | 0.00 |

| Diuretics | 1,506 (5.4) | 2,299 (3.5) | 0.09 | 757 (4.3) | 741 (4.2) | 0.00 |

| ACE inhibitors | 1,020 (3.7) | 1,440 (2.2) | 0.09 | 553 (3.1) | 533 (3.0) | 0.01 |

| ARBs | 8,200 (29.4) | 16,030 (24.3) | 0.11 | 5,129 (28.9) | 5,128 (28.9) | 0.00 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 912 (3.3) | 943 (1.4) | 0.12 | 418 (2.4) | 376 (2.1) | 0.02 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 6,841 (24.5) | 14,734 (22.4) | 0.05 | 4,200 (23.6) | 4,251 (23.9) | −0.01 |

| Urate-lowering agents | 3,129 (11.2) | 5,627 (8.5) | 0.09 | 2,025 (11.4) | 2,059 (11.6) | −0.01 |

| Coronary vasodilators | 696 (2.5) | 1,179 (1.8) | 0.05 | 377 (2.1) | 359 (2.0) | 0.01 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 980 (3.5) | 2,202 (3.3) | 0.01 | 567 (3.2) | 547 (3.1) | 0.01 |

| Chronic heart failure drugs | 48 (0.2) | 2 (0.0) | 0.06 | 3 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 0.00 |

| Xanthine derivatives | 82 (0.3) | 260 (0.4) | −0.02 | 49 (0.3) | 53 (0.3) | 0.00 |

| Number of hospitalizations‡, n | 3,145 | 8,936 | 1,609 | 1,628 | ||

| DPC hospital, n (%) | 2,316 (73.6) | 6,278 (70.3) | 1,165 (72.4) | 1,194 (73.3) | ||

| Non-DPC hospital, n (%) | 829 (26.4) | 2,658 (29.7) | 444 (27.6) | 434 (26.7) | ||

| Number of hospitalizations PPPM†, mean (SD) | 0.0091 (0.0366) | 0.0109 (0.0426) | −0.04 | 0.0074 (0.0341) | 0.0074 (0.0312) | 0.00 |

| Number of outpatient visits PPPM†, mean (SD) | 1.1841 (1.2591) | 1.1380 (1.4428) | 0.03 | 1.1059 (1.1501) | 1.1083 (1.2920) | 0.00 |

| Length of stay per hospitalization, n | 2,371 | 6,039 | 1,263 | 1,224 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.44 (14.62) | 13.53 (22.48) | 8.19 (10.22) | 8.53 (8.95) | ||

| Length of stay per hospitalization per person†, mean (SD) | 0.8013 (5.0061) | 1.2396 (7.8446) | −0.07 | 0.5825 (3.4424) | 0.5876 (3.1916) | 0.00 |

| Number of prescriptions PPPM, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Lipid-lowering agents | 0.2164 (0.3205) | 0.1832 (0.3102) | 0.3154 (1.583) | 0.3213 (2.000) | ||

| P2Y12 inhibitors | 0.0119 (0.0855) | 0.0099 (0.0802) | 0.0105 (0.0802) | 0.0107 (0.0838) | ||

| Warfarin | 0.0043 (0.0547) | 0.0034 (0.0493) | 0.0034 (0.0475) | 0.0034 (0.0475) | ||

| Anticoagulants | 0.0084 (0.0734) | 0.0055 (0.0603) | 0.0062 (0.0624) | 0.0061 (0.0633) | ||

| Low-dose aspirin | 0.0228 (0.1206) | 0.0203 (0.1172) | 0.0205 (0.1139) | 0.0208 (0.1178) | ||

| Beta blockers | 0.0581 (0.1916) | 0.0395 (0.1641) | 0.0506 (0.1792) | 0.0503 (0.1815) | ||

| Alpha blockers | 0.0088 (0.0778) | 0.0067 (0.0692) | 0.0081 (0.0747) | 0.0076 (0.0729) | ||

| Diuretics | 0.0264 (0.1299) | 0.0171 (0.1083) | 0.0203 (0.1128) | 0.0209 (0.1178) | ||

| ACE inhibitors | 0.0181 (0.1077) | 0.0118 (0.0897) | 0.0156 (0.0999) | 0.0160 (0.1030) | ||

| ARBs | 0.1665 (0.2971) | 0.1409 (0.2843) | 0.1626 (0.2935) | 0.1647 (0.2973) | ||

| Aldosterone antagonists | 0.0162 (0.1018) | 0.0072 (0.0690) | 0.0115 (0.0857) | 0.0108 (0.0840) | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 0.1277 (0.2644) | 0.1244 (0.2707) | 0.1220 (0.2584) | 0.1300 (0.2710) | ||

| Urate-lowering agents | 0.0584 (0.1886) | 0.0466 (0.1740) | 0.0598 (0.1912) | 0.0626 (0.1980) | ||

| Coronary vasodilators | 0.0053 (0.0504) | 0.0045 (0.0491) | 0.0047 (0.0485) | 0.0050 (0.0517) | ||

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 0.0096 (0.0733) | 0.0086 (0.0685) | 0.0080 (0.0636) | 0.0081 (0.0666) | ||

| Chronic heart failure drugs | 0.0005 (0.0163) | 0.0000 (0.0046) | 0.0000 (0.0021) | 0.0001 (0.0088) | ||

| Xanthine derivatives | 0.0004 (0.0114) | 0.0006 (0.0142) | 0.0005 (0.0135) | 0.0004 (0.0097) | ||

| Number of diabetes-related prescriptions PPPM, mean (SD) | 0.1914 (0.3127) | 0.1494 (0.2870) | 0.1713 (0.2990) | 0.1665 (0.2955) | ||

| All-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM†, $, mean (SD) | 228.2 (586.4) | 234.4 (743.9) | −0.01 | 187.9 (396.9) | 183.3 (408.4) | 0.01 |

| All cause hospitalization costs PPPM†, $, mean (SD) | 61.3 (451.0) | 77.1 (462.7) | −0.03 | 44.3 (294.4) | 42.3 (270.7) | 0.01 |

| All-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM†, $, mean (SD) | 141.6 (198.5) | 130.6 (274.0) | 0.05 | 126.1 (152.8) | 125.3 (209.2) | 0.00 |

| All-cause pharmacy costs PPPM†, $, mean (SD) | 25.3 (186.5) | 26.7 (366.0) | 0.00 | 17.5 (141.2) | 15.7 (123.1) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes-related pharmacy costs PPPM, $, mean (SD) | 7.6 (31.0) | 1.6 (11.9) | 3.7 (20.0) | 2.1 (13.4) | ||

- All costs are reported in USD.

- † Variables used to calculate propensity score.

- ‡ Number of hospitalizations was the sum of the number of DPC hospitalizations and the number of non-DPC hospitalizations. Percentages were calculated using the total number of hospitalizations for each treatment group as the denominator.

- ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; aDCSI, adapted Diabetes Complication Severity Index; ARB, angiotensin-II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; DPC, Diagnosis Procedure Combination; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; IQR, interquartile range; oGLD, other glucose-lowering drug; PPPM, per person per month; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Treatment persistence

The proportions of early dropouts were similar between the treatment groups (12.3% vs 10.1% in the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups, respectively). Before matching, treatment persistence was numerically greater in the DPP4i group than in the SGLT2i group, regardless of the early dropout patients (Table S7). After matching, treatment persistence was similar between the treatment groups.

HCRU

All HCRU endpoints were significantly lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group (Table 2). The mean number of hospitalizations PPPM was lower in the SGLT2i group (0.0179) than in the DPP4i group (0.0263) (LSM difference [95% CI] −0.00846 [−0.01059, −0.00634]; P < 0.0001). The mean length of stay per hospitalization and mean length of stay per hospitalization per person were significantly shorter in the SGLT2i group than in the DPP4i group (Table 2). Patients in the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups had a similar proportion of DPC (74.7% vs 72.8%) and non-DPC (25.3% vs 27.2%) hospitalizations. The mean number of outpatient visits PPPM was 1.5466 and 1.6215 days in the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups, respectively (LSM difference [95% CI] −0.07491 [−0.10256, −0.04726]; P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

| SGLT2i (n = 17,767) | DPP4i (n = 17,767) | LSM difference (95% CI) | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitalizations PPPM | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.0179 (0.0867) | 0.0263 (0.1155) | −0.00846 (−0.01059, −0.00634) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay per hospitalization per person, days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.82 (3.79) | 1.25 (6.10) | −0.426 (−0.531, −0.320) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay per hospitalization | ||||

| n | 1,599 | 1,958 | ||

| Mean (SD), days | 9.11 (9.18) | 11.30 (14.97) | −2.192 (−3.032, −1.353) | <0.0001‡ |

| Number of outpatient visits PPPM | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5466 (1.2650) | 1.6215 (1.3908) | −0.07491 (−0.10256, −0.04726) | <0.0001 |

- † Paired t-test.

- ‡ t-test.

- CI, confidence interval; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; LSM, least squares mean; PPPM, per person per month; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

Healthcare costs

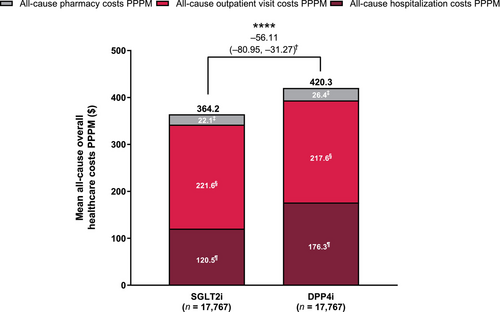

Healthcare costs PPPM were generally lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group (Figure 1). Mean all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM were significantly lower in the SGLT2i group ($364.2; ¥41,948.6) than in the DPP4i group ($420.3; ¥48,411.0) (LSM difference [95% CI]: $−56.11 [−80.95, −31.27]; ¥−6,462.33 [−9,323.00, −3,601.67]; P < 0.0001). Mean all-cause hospitalization costs PPPM were significantly lower in the SGLT2i group ($120.5; ¥13,875.7) vs the DPP4i group ($176.3; ¥20,306.8) (LSM difference [95% CI]: $−55.84 [−78.85, −32.83]; ¥−6,431.07 [−9,081.64, −3,780.50]; P < 0.0001). There was no significant difference in all-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM and all-cause pharmacy costs between the treatment groups. All-cause healthcare costs were slightly greater in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group up to the 80th percentile of patients, although it was <$340 (¥40,000) in both treatment groups (Figure S3). The all-cause overall healthcare costs substantially rose in the ≥85th percentile of patients in both treatment groups, and became greater in the DPP4i group than in the SGLT2i group; in the 99th percentile of patients, the costs reached $3,385.5 (¥389,903.3) and $5,065.7 (¥58,3420.0) in the SGLT2i and DPP4i groups, respectively.

HCRU and healthcare costs in the BMI subcohorts

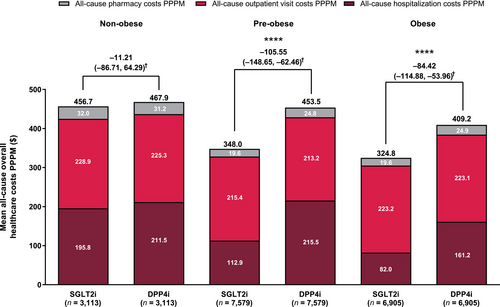

Among the non-obese subcohort, the SGLT2i group had a significantly shorter mean length of stay per hospitalization and per hospitalization per person than the DPP4i group, but there was no difference in the numbers of hospitalizations or outpatient visits PPPM or any of the healthcare cost outcomes between the groups (Table 3; Figure 2). Among the pre-obese subcohort, all HCRU and most healthcare cost endpoints were lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group. Among the obese subcohort, all HCRU and healthcare cost endpoints, except for all-cause outpatient visit costs and pharmacy costs PPPM, were lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group. Differences in the all-cause overall healthcare costs between treatment groups were greater in the pre-obese and obese subcohorts than in the non-obese subcohort.

| Non-obese | Pre-obese | Obese | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i (n = 3,113) | DPP4i (n = 3,113) | SGLT2i (n = 7,579) | DPP4i (n = 7,579) | SGLT2i (n = 6,905) | DPP4i (n = 6,905) | |

| Number of hospitalizations PPPM | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.0244 (0.1101) | 0.0285 (0.1264) | 0.0162 (0.0774) | 0.0284 (0.01191) | 0.0166 (0.0814) | 0.0256 (0.1150) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −0.00413 (−0.01002, 0.00176) | −0.01220 (−0.01539, −0.00900) | −0.00892 (−0.01225, −0.00560) | |||

| P value† | 0.1709 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Length of stay per hospitalization per person | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.91 (3.76) | 1.59 (9.06) | 0.79 (3.56) | 1.32 (5.91) | 0.80 (3.57) | 1.16 (4.92) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −0.678 (−1.023, −0.334) | −0.530 (−0.686, −0.375) | −0.361 (−0.504, −0.217) | |||

| P value† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Length of stay per hospitalization, n | 312 | 380 | 669 | 886 | 606 | 708 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.09 (8.17) | 13.02 (22.92) | 8.93 (8.41) | 11.28 (13.68) | 9.10 (8.37) | 11.31 (11.04) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −3.930 (−6.607, −1.252) | −2.351 (−3.527, −1.175) | −2.209 (−3.284, −1.134) | |||

| P value‡ | 0.0041 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| Number of outpatient visits PPPM | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5507 (1.2872) | 1.5899 (1.4006) | 1.5221 (1.2382) | 1.5980 (1.3499) | 1.5708 (1.2836) | 1.6482 (1.4121) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −0.03921 (−0.10605, 0.02763) | −0.07594 (−0.11718, −0.03470) | −0.07743 (−0.12245, −0.03242) | |||

| P value† | 0.2529 | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | |||

- † Paired t-test.

- ‡ t-test.

- BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; LSM, least squares mean; PPPM, per person per month; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

HCRU and healthcare costs in vascular complication subcohorts

Among all vascular complication subcohorts, most HCRU outcomes, all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM, and all-cause hospitalization PPPM were lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group (Table S8; Figure S4). All-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM were significantly lower in the DPP4i group vs the SGLT2i group only among the subcohort with no vascular complications. All-cause pharmacy costs PPPM were similar between the treatment groups among all subcohorts.

Subgroup analyses

All-cause overall healthcare cost quartiles

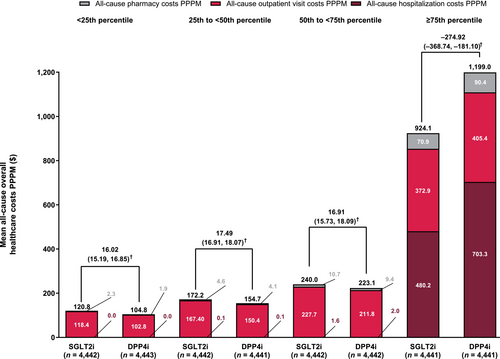

The mean number of hospitalizations PPPM was significantly lower and the length of stay per hospitalization was significantly shorter in the SGLT2i group than in the DPP4i group among the ≥75th percentile subgroup (Table 4). The number of outpatient visits PPPM was significantly lower in the SGLT2i group vs the DPP4i group among the 50th to <75th and ≥75th percentile subgroups. Within each treatment group, the number of hospitalizations PPPM and outpatient visits PPPM were numerically higher in the ≥75th percentile subgroup than other percentile subgroups. All-cause overall hospitalization costs PPPM, all-cause outpatient costs PPPM, and all-cause pharmacy costs were significantly lower among the ≥75th percentile subgroup, but significantly higher among the other percentile groups in the SGLT2i group than in the DPP4i group (Figure 3). Within each treatment group, healthcare costs PPPM, particularly all-cause hospitalization costs, were substantially higher in the ≥75th percentile subgroup than in the other percentile subgroups (Figure 3).

| <25th percentile | 25th to <50th percentile | 50th to <75th percentile | ≥75th percentile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i (n = 4,442) | DPP4i (n = 4,443) | SGLT2i (n = 4,442) | DPP4i (n = 4,441) | SGLT2i (n = 4,442) | DPP4i (n = 4,442) | SGLT2i (n = 4,441) | DPP4i (n = 4,441) | |

| Number of hospitalizations PPPM | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.0002 (0.0071) | 0.0001 (0.0029) | 0.0002 (0.0039) | 0.0003 (0.0051) | 0.0018 (0.0144) | 0.0019 (0.0132) | 0.0692 (0.1621) | 0.1030 (0.2129) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | 0.00016 (−0.00006, 0.00039) | −0.00008 (−0.00027, 0.00011) | −0.00012 (−0.00070, 0.00045) | −0.03382 (−0.04169, −0.02595) | ||||

| Length of stay per hospitalization per person | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.03 (1.19) | 0.06 (3.90) | 0.01 (0.30) | 0.01 (0.21) | 0.07 (0.95) | 0.12 (2.61) | 3.18 (6.91) | 4.80 (10.49) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −0.031 (−0.151, 0.089) | 0.001 (−0.010, 0.012) | −0.053 (−0.134, 0.029) | −1.621 (−1.990, −1.251) | ||||

| Length of stay per hospitalization, n | 7 | 4 | 10 | 14 | 84 | 98 | 1,498 | 1,842 |

| Mean (SD) | 19.29 (24.69) | 67.75 (128.20) | 4.20 (5.09) | 2.71 (2.79) | 3.44 (6.06) | 5.34 (16.86) | 9.41 (9.10) | 11.56 (13.67) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −48.464 (−157.237, 60.308) | 1.486 (−1.862, 4.834) | −1.896 (−5.724, 1.932) | −2.149 (−2.957, −1.342) | ||||

| Number of outpatient visits PPPM | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.8690 (0.3228) | 0.8751 (0.3400) | 1.2033 (0.5185) | 1.2096 (0.4645) | 1.6438 (0.8556) | 1.7098 (0.8578) | 2.4706 (1.9640) | 2.6918 (2.1891) |

| LSM difference (95% CI) | −0.00617 (−0.01996, 0.00761) | −0.00632 (−0.02679, 0.01416) | −0.06607 (−0.10170, −0.03044) | −0.22119 (−0.30769, −0.13468) | ||||

- CI, confidence interval; DPP4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; LSM, least squares mean; PPPM, per person per month; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

Baseline number of oGLDs

Healthcare resource utilization was generally lower in the SGLT2i group than in the DPP4i group regardless of the baseline number of oGLDs (Table S9). Compared with DPP4i, SGLT2i had significantly lower overall healthcare costs PPPM and all-cause hospitalization costs PPPM among patients who were oGLD naïve or those using oGLD multitherapy, significantly lower all-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM among patients using oGLD monotherapy, and significantly lower all-cause pharmacy costs PPPM among patients who were oGLD naïve. However, in patients who were oGLD naïve, all-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM were significantly lower in the DPP4i group vs the SGLT2i group.

Patients without hospitalization during follow-up

Among patients without hospitalization during follow-up, the number of outpatient visits was significantly lower in the SGLT2i group than in the DPP4i group (Table S10). However, all-cause overall healthcare costs PPPM and all-cause outpatient visit costs PPPM were significantly lower in the DPP4i group than in the SGLT2i group. There was no difference in all-cause pharmacy costs PPPM observed between the groups.

DISCUSSION

This large retrospective study using the JMDC Claims Database compared HCRU and healthcare costs for SGLT2i vs DPP4i in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan. In this study, the numbers of hospitalizations and outpatient visits were lower, and the length of hospital stay was shorter, in patients newly treated with an SGLT2i than in those newly treated with a DPP4i. Although all-cause outpatient visit costs and pharmacy costs were similar between treatments, all-cause overall healthcare costs and hospitalization costs were lower with SGLT2i than with DPP4i. These results suggest that SGLT2i is associated with lower HCRU and healthcare costs, particularly those related to hospitalization, vs DPP4i, demonstrating the economic benefits of SGLT2i use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan.

In this study, patients treated with an SGLT2i or a DPP4i had similar proportions of DPC and non-DPC hospitalizations. Consistent with previous studies17, 18, 22, SGLT2i use resulted in lower numbers of hospitalizations and outpatient visits and shorter length of hospital stay than for those treated with a DPP4i. In a real-world US study, significantly lower all-cause inpatient and outpatient HCRU PPPM, and a numerically shorter stay per inpatient visit, was observed in patients treated with empagliflozin vs oGLDs17. A retrospective study using databases from East Asia, including Japan, reported that patients treated with empagliflozin had a reduced risk of all-cause hospitalization, first hospitalization, emergency room visits, and outpatient visits than those treated with DPP4i22; the length of stay in patients with ≥1 hospitalization was lower with SGLT2i than with DPP4i (13.4 vs 15.5 days). A Japanese cost-utilization analysis study also showed that SGLT2i use was associated with a lower frequency of hospitalization and a shorter hospital stay vs DPP4i or oGLDs use18. In this study, mean all-cause overall healthcare costs were also significantly lower in patients treated with an SGLT2i ($364.2 PPPM or $4,370.8 per person per year) vs a DPP4i ($420.3 PPPM or $5,044.1 per person per year). This is mainly attributed to the difference in the overall hospitalization costs between SGLT2i and DPP4i, consistent with the results of previous studies9-12. Together, the results indicate that SGLT2i are associated with reduced HCRU and healthcare costs, particularly in relation to hospitalization, compared with DPP4i in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japan; hospitalization greatly impacts HCRU and healthcare costs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the economic benefits of SGLT2i are dependent on its effects of reducing hospitalization.

Outpatient visit costs were numerically higher with SGLT2i vs DPP4i. SGLT2i is associated with an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis23, 24 and genitourinary infections25-27; as such, the higher outpatient visit costs may be due to the costs of blood and urine testing to monitor potential SGLT2i-related adverse events. Conversely, given that SGLT2i have cardiorenal and hepatoprotective effects9-12, 28, 29, they may have been prescribed to patients with more severe comorbidities and complications, although information on severity is unknown. To monitor comorbidities and complications, patients may have had more medical examinations at each outpatient visit, and the costs of such examinations may have also contributed to the higher outpatient visit costs with SGLT2i. Although the average cost of SGLT2i is higher than that of DPP4i, all-cause pharmacy costs PPPM were similar and appeared low (<$30) with both treatments. This may be because pharmacy costs during DPC hospitalization were not recorded as pharmacy costs.

In this study, SGLT2i demonstrated significantly lower HCRU and costs, especially related to hospitalization, only among pre-obese and obese patients. The WHO's BMI classification for obesity was used in this study; however, Asian populations are at high risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVD even at BMIs lower than the WHO criteria for pre-obese30, and a BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2 is classified as mild obesity (obesity class I) in Japan31. Therefore, the results suggest that economic benefits can be expected with early initiation of SGLT2i in patients who are pre-obese or have mild obesity. Among non-obese patients, the economic benefits of SGLT2i may have been limited because (1) these patients generally have fewer cardiometabolic risks and complications, resulting in similar clinical benefits between SGLT2i and DPP4i, or (2) patient characteristics in this subcohort appeared heterogenous in terms of severity of glycemic control and vascular complications and included those with more severe baseline conditions and high risk of hospitalization (Table S5); given the results from a previous study9, the effect of SGLT2i may have been reduced. Conversely, SGLT2i generally demonstrated greater economic advantages over DPP4i in patients with macro- and microvascular diseases and those using multiple oGLDs at baseline. Comorbidities and chronic diabetes complications have been reported to be predictors for hospitalization32, and CVD-related complications are common reasons for hospitalization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus33, 34. Therefore, the results again suggest that the lower HCRU and costs observed may be largely related to the reduced hospitalizations associated with SGLT2i.

The strengths of this study included use of the JMDC Claims Database, which enabled the collection of longitudinal patient data from a large sample of >17,000 matched patients from each treatment group, the inclusion of younger patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the evaluation of various HCRU and healthcare cost endpoints.

The limitations of this study included the presence of potential unobservable confounding factors that could not be accounted for; also, because the JMDC Claims Database collects data of individuals and their dependents who are insured through their employers, data for patients aged ≥75 years are limited. Laboratory test data were limited to tests performed as part of annual health check-ups only, and it is unknown if patients took the prescribed drugs because treatment groups were determined using drug claims from the database. Furthermore, coding errors and disease names used only for insurance claims may be present, and data outliers may have greatly affected the results for some subgroups with small sample sizes. Of note, results from this study are derived after propensity score matching, which made the characteristics of patients in the DPP4i group more similar to those in the SGLT2i group.

In conclusion, this large, retrospective cohort study demonstrated lower HCRU and healthcare costs with SGLT2i vs DPP4i in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a real-world clinical setting in Japan. The results showed that hospitalization substantially influences HCRU and healthcare costs, suggesting that drugs that potentially prevent or shorten hospitalization such as SGLT2i may demonstrate economic benefits in type 2 diabetes mellitus management. The findings from this study may assist healthcare professionals in selecting appropriate treatments for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc., who was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. Medical writing assistance was provided by Envision Pharma Group, funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. We thank Hiroyuki Okumura, PhD, a former employee of Astellas Pharma Inc., who assisted with the development of the protocol and the final study report.

DISCLOSURE

A.K. received funding as an adviser for Sunstar Group. S.S., Y.K., Y.Y., and M.R. are employees of Astellas Pharma Inc.

Approval of the research protocol: Medical Affairs Japan – Protocol Review Committee (protocol no. 1941-MA-1631).

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant level data, trial level data, and protocols from Astellas sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing, see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.