China as a Catalyst of the European Union's Trade Defence Instruments

Abstract

Scholars have paid significant attention to the ‘geopoliticisation’ and ‘securitisation’ turn in EU trade policy. As part of this shift, the EU has begun to develop autonomous trade defence instruments under the ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’ toolbox, to find a new balance between security and competitiveness. This article offers a thorough descriptive and discursive framing analysis of a broad dataset comprising speeches and press releases from EU institutions and mainstream media that link China to the development of these trade defence instruments. This provides a comprehensive account of the ‘China factor’ in accounting for the enactment of these instruments, showing that it precedes other factors generally associated with the geopolitical turn in EU trade policy, like the COVID-19 and Ukraine crises. It reveals that the foundations of the link between the China factor and the EU's trade defence instruments are deeply tied together at the level of communicative discourse, which provides insights on the heterogeneity of narratives on China in EU trade discourse, challenging the popular claim that the instruments are ‘country-agnostic’ at the level of communicative discourse. The findings of this article are significant for understanding China's influence on EU trade and economic policy.

Introduction

Scholars have devoted significant attention to the so-called ‘geopoliticisation’ (Meunier, 2022) and ‘securitisation’ (Rogelja and Tsimonis, 2020) turn in EU trade policy. This shift, it is argued, is based on the recognition that, as great power competition continues to intensify and trade practices are increasingly subject to geopolitical considerations, the playing field has become unbalanced against a pro-free trade EU, which has been portrayed as falling victim to its own ‘naïveté’. The change in policy and discourse was already hinted at in the 2015 Commission's ‘Trade for All’ strategy, which called for a more balanced approach to globalisation (Dimitropoulos, 2020), and was further solidified in the 2016 EU Global Strategy, which framed trade policy as inherently geopolitical (Meunier and Nicolaidis, 2019). This direction was reinforced in 2019 with Commission President von der Leyen's declaration of a ‘geopolitical Commission’ and, more specifically, by the 2021 Trade Policy Review, which advocated for an open, sustainable, and assertive approach to trade. Structured around the concept of ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’ (OSA), the Review outlines a dual strategy of active engagement with key partners whilst simultaneously applying autonomous instruments to safeguard the EU's interests and values (Blockmans, 2021; Eliasson and Garcia-Duran, 2023; Jacobs et al., 2023; Schmitz and Seidl, 2023). Against this backdrop, the European Union began to develop autonomous trade defence instruments (TDIs) under the OSA framework, which are defined as mechanisms to protect European production from international trade distortions (EC, n.d.). Whilst the primary objective of these instruments is to strike a new balance between security and competitiveness – ensuring the EU's future ability to ‘pursue its interests and enforce its rights, including autonomously where needed’ (EC, 2021) – the Union's TDIs encompass a broad range of specific goals.

In explaining this geopolitical turn in EU trade policy, scholars have identified several driving factors, including the increasing perception of an assertive China across Europe (Freeman, 2022; Meunier, 2022), the supply chain disruptions triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war and the protectionist policies adopted by the Trump and Biden administrations in the United States. This article focuses on the specific – and arguably central – role of China in the EU's enactment of TDIs by examining the discourses of EU policy-makers and the media (Schmidt, 2008). The analysis demonstrates that the EU's trade defence reforms preceded some of the commonly cited factors associated with the geopolitical turn in EU trade policy and specifically ties these reforms to concerns about China. To support this argument, I trace China's role as a justification in official EU discourse and mainstream media, highlighting the narratives constructed to legitimise the creation and necessity of these instruments. The findings reveal that the link between China and the EU's TDIs is deeply entrenched at the level of communicative discourse, which is understood as a dual mass process of public persuasion by political actors and the media to present, deliberate and legitimise political ideas to the general public (Schmidt, 2008, p. 310).

Using a mixed-method text analysis approach, this article investigates how the European Union has invoked China to legitimise its TDIs, which are a key element of its evolving trade policy. The analysis focuses on the new trade instruments adopted by the European Union to safeguard its geo-economic interests (Meunier, 2022), specifically the Foreign Direct Investment Screening Mechanism (FDI SM), the International Procurement Instrument (IPI), the Foreign Subsidies Instrument (FSI), the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) and the 5G cybersecurity toolbox. Other unilateral instruments include the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the updated Trade Enforcement Regulation, alongside ‘traditional’ trade defence tools such as anti-dumping, anti-subsidy and safeguard measures (Couvreur et al., 2022). However, the instruments selected for this analysis exemplify the ‘geopoliticisation’ of the EU's trade policy and represent a sufficiently diverse set of configurations and purposes – some designed to create a level playing field, counter unfair trade practices or promote economic security and the securitisation of trade. Whilst some scholars have focused on individual instruments (Couvreur et al., 2022; Freudlsperger and Meunier, 2024) and others have taken a broad-brush approach that acknowledges China's influence on the EU's policy shift (Erixon et al., 2021; Meunier, 2022; Van der Loo, 2021), this article opens the ‘black box’ by uncovering the specific discursive strategy employed by EU institutions and media outlets to legitimise its TDIs through references to China. It offers a comprehensive descriptive and discursive framing analysis of a broad dataset comprising speeches and press releases from EU institutions and mainstream media that link China to the development of these TDIs.

This study highlights the connection between narratives and instruments, uncovering the discursive strategy employed by two key actors in the EU – its political institutions and the media – to justify TDIs by referencing China. It posits the hypothesis that the both institutional and media trade discourse in the EU have employed a heterogeneous set of narratives to legitimise these instruments, to shape a specific perception of China amongst the European public, albeit in different ways. This challenges the prevailing claim that TDIs are ‘country-agnostic’ at the level of communicative discourse. By examining the instruments comprehensively, the analysis draws both parallels and distinctions in how they have been legitimised, despite forming part of a broader, unified trade strategy.

The findings of this article are significant for understanding China's influence on EU trade and economic policy discourse, particularly in its shift towards open strategic autonomy and the ‘geopoliticisation’ of EU trade policy. The following section reviews existing scholarship on the geo-economic turn in EU trade policy and EU–China economic relations, tracing the evolution of the EU's trade discourse as it pertains to China. Section II outlines the methodology employed for both software-assisted and in-depth text analysis, as well as the dataset used. Section III presents the findings of the study, whilst the final section offers key conclusions.

1 Literature Review

To understand how EU institutions and media discourses have used China to legitimise the TDIs, this article builds on academic literature that examines the broader external shifts in EU trade policy by analysing macro-level factors and trends that have driven its securitisation (Chan and Meunier, 2021; Schmitz and Seidl, 2023). The literature shows that scholars have explored how China has been a key factor in prompting the EU's geo-economic turn and its adoption of a more geopolitical approach to trade. Other relevant external factors that have contributed to the trend towards securitisation and geopoliticisation in EU trade policy include the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 – which underscored the risks of economic interdependence – a crisis in multilateralism (Zürn, 2021), the resurgence of trade wars between major powers (e.g., the United States and China in 2018) and the growing use of sanctions, which have transformed trade policy into an ‘essential tool of geopolitics’ (Meunier and Nicolaidis, 2019). In response to this complex environment, the European Commission's increasing emphasis on strategic autonomy has further blurred the lines between foreign, security and trade policy (Jacobs et al., 2023; Juncos and Vanhoonacker, 2024; Schmitz and Seidl, 2023). This more volatile external environment, or ‘new global disorder’ (Lavery and Schmid, 2021), has driven the European Union towards a shift from unconditional openness to a more qualified openness, encapsulated by the concept of ‘Open Strategic Autonomy’ (EC, 2021).

Whilst scholars have broadly explored the macro-level trends and factors driving the securitisation of trade in Europe and have consistently linked China to these developments, this article takes a more specific approach by examining how TDIs have been rhetorically tied to China in EU institutional and media discourses as a key reason for their legitimacy and necessity. Rather than providing an exhaustive analysis of all factors legitimising TDIs, the article situates its argument within the global trend towards the securitisation and geopoliticisation of trade, with the EU–China relationship serving as a critical case study. It seeks to link these general external drivers to the specific case of TDIs, demonstrating the relative influence of external factors on individual EU policies. This approach offers a more focused, empirically grounded analysis. In doing so, it builds on existing literature regarding the role of European perceptions of China in the evolution of EU trade policy (Perceptions in an Evolving EU–China Economic Relationship section) and discourse (The Evolution of the EU's Trade Discourse section). Specifically, it analyses China's subjective influence on the creation of TDIs, which has been widely acknowledged but rarely examined in detail regarding the precise characteristics of the EU–China relationship that explain the instruments' emergence and necessity. By taking the TDIs as a case study and China as a critical external factor, this article seeks to advance the existing body of literature by providing a nuanced analysis of their interrelation.

Perceptions in an Evolving EU–China Economic Relationship

The Constructivist school of International Relations has extensively examined how perceptions shape foreign policy (Herrmann and Shannon, 2001; Jervis, 1976), including in the context of EU–China relations (Freeman, 2022; Möller, 2002). Building on these studies, this article delves deeper into which specific attributes of China have been adopted by EU policy-makers to justify the creation and redefinition of TDIs. It further examines whether these perceptions are echoed in media narratives that seek to legitimise the instruments in the eyes of the European public. Historically, economic relations have been central to the EU–China relationship, shaping European views of China. Since 2001, however, the European Union has recognised both positive and negative dimensions in its engagement with China, stemming from an imbalance in their economic relationship and China's increasing assertiveness. Beginning in 1995, the European Union pursued a policy of constructive engagement with China, supporting its integration into the global economic system and advocating for its accession to the WTO, based on expectations that China would reciprocate by gradually opening its economy (Freeman, 2022). After 2006, the principles of reciprocity and a level playing field became cornerstones of EU–China policy. Whilst the European Union continued to promote a co-operative relationship, it increasingly emphasised balance and mutual interests, focusing on areas such as sustainable development and regional co-operation, with the belief that engagement would encourage China towards a more liberal economic and political trajectory.

Nevertheless, a perceptible shift began to influence EU policy, as evidenced by the 2016 EU Strategy on China (EC, 2016), which adopted a stance of ‘principled pragmatism’. This marked a more selective approach to economic engagement and indicated a growing mistrust towards China. The 2019 EU-China Strategic Outlook (EC, 2019) further exemplified this change, categorising China as a ‘partner, competitor, and rival’, reflecting a perception that China was presenting alternatives to the liberal economic order and its associated values. The Outlook underscored the necessity of enhancing EU unity and competitiveness in response to China. It also conveyed a more critical view of China's domestic reforms and global role, implicitly acknowledging the limited success of the EU's market and normative power in influencing China and advocating for a new approach (EC, 2019).

Scholars have acknowledged that China has been a key factor in shaping the EU's reconceptualisation of its trade policy (De Ville, 2019), noting that political and media discourses have often disproportionately emphasised Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe relative to its actual size (Chan and Meunier, 2021). This disproportionate attention can partly be attributed to the cultural distance between the European Union and China, China's authoritarian political system and its status as a non-security ally (Meunier, 2019). Currently, EU–China relations are characterised by misunderstandings and misperceptions, with both sides often speaking past rather than to each other (Men, 2022). Within the EU, China is perceived as having reneged on implicit expectations of economic liberalisation and political reform – expectations it never explicitly committed to fulfilling (Fox and Godement, 2009). Against this backdrop, this article investigates the connection between shifting EU perceptions of China and changes in policy discourse identified in existing literature. In essence, it seeks to pinpoint the shared narratives, derived from fluid perceptions of China in Europe, that have arguably driven changes in EU trade policy, focusing on the specific case of TDIs.

The Evolution of the EU's Trade Discourse

This article sheds new light on the shift in the EU's trade discourse, as identified in the academic literature, by delving into China as a factor in influencing the perceived shift towards the ‘geopoliticisation’ (Leblond and Viju-Miljusevic, 2019; Meunier and Czesana, 2019; Meunier and Nicolaidis, 2019) and ‘securitisation’ (Roberts et al., 2019) of trade from around 2010, as well as the evolving meaning of the ‘free trade’ narrative, with TDIs serving as a key case in point. Discourse constructs meaning through processes of differentiation or ‘othering’ (De Ville and Orbie, 2013). These ‘othering’ practices encompass both temporal and geographical dimensions (Diez, 2004), and in this analysis, they specifically target China. Specifically, how China is portrayed as a ‘geographical other’ by EU policy-makers or the media to articulate a European identity against it and legitimise the EU's trade and investment agenda (De Ville and Orbie, 2013).

Thus, this article studies how this is captured in the communicative discourse surrounding EU TDIs. Specifically, it examines political discourse as represented in speeches, press releases and media articles, identifying the main narratives that link China to the OSA instruments. Political communication is understood here as a discursive, top-down process by which policy-makers seek to legitimise trade instruments that mark a significant shift in EU trade policy. Whilst the co-ordinative discourse (Schmidt, 2008) – the internal reasons and negotiations behind the creation of these instruments – falls outside the scope of this article, the analysis explores the narratives used by both EU institutions and the media to justify the TDIs. This research does not assume a co-ordinated legitimation effort between political institutions and the media but rather seeks to infer and compare the discursive strategies of both actors, who interact dynamically in shaping policy outcomes (Baum and Potter, 2008). The media plays a critical role in transmitting information from policy-makers to the public whilst simultaneously serving as a source of information for policy-makers themselves, in what has become a ‘mediated society’ (Zhang, 2022). Policy-makers package policy in preferred frames, but the media plays a crucial role in framing and distributing this information, influencing public perceptions of ‘self’ and ‘other’ in EU–China relations (Zhang, 2022). This dual process of legitimation – by policy-makers and the media, according to their singular strategies and interests – forms the basis of the subsequent analysis of narratives used to influence public perceptions and drive further policy development.

The EU's trade discourse has evolved considerably in the last two decades. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the European Union adopted a trade liberalisation agenda aimed at restoring economic growth (Bollen et al., 2016). Scholars have noted the European Commission's discursive efforts to legitimise neoliberal trade policies by subtly rearticulating the relationship between free trade and post-crisis recovery (De Ville and Orbie, 2013). As early as 2006, the Global Europe strategy under Commissioner Mandelson hinted at the need to adapt the EU's TDIs. Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht later adopted a more critical stance towards China, denouncing the EU's previous ‘naïveté’ in the Commission's Trade, Growth, and World Affairs strategy.

A pivotal moment occurred in 2013, when the European Union withdrew from an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese solar panels following retaliatory measures by China. This episode is widely regarded as a diplomatic victory for China (Bollen et al., 2016) and catalysed stronger support for reforming the EU's TDIs. Under Commissioner Malmström, the European Union subsequently strengthened its unilateral trade toolbox, partially due to a shift in Germany's stance (De Ville, 2019). This reflects a broader transformation in the positions of traditionally ‘dovish’ member states, which assumed a more ‘hawkish’ outlook towards China (De Ville, 2019). The shift in member states' attitudes enabled the Commission to move forward with enacting trade instruments under the OSA framework – policy ‘sticks’ designed to enhance the EU's leverage in opening foreign markets, ensuring reciprocity and demonstrating that liberalisation ‘works’ (Siles-Brügge, 2014, p. 50).

This article closely examines the evolution of the EU's trade discourse towards China to understand how protectionist instruments were legitimised in political communication, which opened the door for a shift towards protectionist policies – an idea that had previously faced significant resistance amongst member states in the 2010s. The findings suggest that external geopolitical and geo-economic factors, rather than internal changes, were instrumental in driving this shift. China was portrayed as a pervasive external influence, prompting a rally-around-the-flag effect that mitigated political and social opposition to protectionist policies. This occurred in the context of a paradigm shift towards the securitisation and politicisation of trade (EC, 2021), compounded by social backlash against the CETA and TTIP agreements.

Whilst the trade–security nexus in EU policy has gained increasing academic attention in recent years (Bown, 2024; Meunier and Danzman, 2024; Orbie et al., 2012; Stueber, 2022), the Lisbon Treaty had already expanded the EU's role in foreign and security policies in 2009, aiming to reduce the compartmentalisation of trade and security. However, it was not until the 2021 Trade Policy Review that security considerations were explicitly integrated into trade policy, portraying trade as a tool to advance strategic interests. This shift led to the development of various innovative policy instruments that blend trade and security concerns (Rosén and Meunier, 2023), including the TDIs examined in this article. The EU's emphasis on addressing competitive distortions, ensuring a level playing field and promoting economic fairness can be seen as a direct response to China's trade policies, which ended the notion that trade flows are purely neutral and devoid of security implications (Comerma, 2024). The OSA instruments aim to address specific trade vulnerabilities: the 5G toolbox and FDI SM focus on restricting certain types of investment inflows into Europe, an objective that may soon be shared by an outbound investment screening mechanism currently under discussion (EP, 2023); the FSI is designed to ensure ‘fair’ competition within the EU market; and the IPI and ACI seek to open foreign markets. Whether this diversity in objectives is reflected in the discourse will be explored in the subsequent analysis. The 2023 Economic Security Strategy (EC, 2023a) further reinforces this paradigm shift in EU trade policy.

There is broad academic consensus that a major driver of the EU's shift in trade policy has been policy-makers' perception of an increased threat from rising Chinese investment, which stemmed from China's 1998 ‘Go Out’ policy, the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 and the ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy (Chan and Meunier, 2021). This investment primarily targeted three categories of EU firms: financially distressed companies, competitive niche producers and former partners or subcontractors (Nicolas, 2014). Notably, a significant portion of these investments has been made by Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Hanemann et al., 2019; Nicolas, 2014). These SOEs are seen as potentially engaging in unfair competition due to their access to large state subsidies (Van der Loo and Hahn, 2020) and have raised security concerns because of their close ties to the Chinese government, particularly in sectors involving critical technologies and large infrastructure projects (Grieger, 2019). Another contributing factor has been China's use of economic statecraft (Ferchen and Mattlin, 2023), defined as ‘the use of economic resources by political leaders to exert influence in pursuit of foreign policy objectives’ (Reilly, 2013). China's application of economic statecraft has become more frequent, assertive and diverse, employing a mix of incentives (such as foreign aid, state purchases, generous trade agreements and cross-border infrastructure projects) and coercive measures (such as sanctions, vague threats and leadership-level diplomatic variations) (Reilly, 2013).

Overall, this article argues that there has been a paradigm shift in EU–China relations, moving from an era of economic opportunism to one of more conditional, value-based engagement. This shift is reflected in the EU's trade discourse, which has increasingly sought to legitimise protective measures against China. By identifying and analysing the specific characteristics of China that have been highlighted in EU discourse, this study advances the understanding of the ideational framework behind the EU's approach to China, particularly as the European Union moves towards implementing the OSA instruments and broader strategies of economic security and strategic autonomy.

2 Methodology

The methodology used to analyse how EU policy-makers and the media have employed China to legitimise the new TDIs combines qualitative and quantitative text analysis. First, an in-depth qualitative text analysis was conducted using an inductive approach during the initial reading of the texts to infer the main narratives linking China to the instruments under study. This process was guided by a review of relevant academic literature. Specifically, the author examined the documents and abstracts that referenced China in relation to each instrument, identifying the causal connections being made – for example, whether the instrument was justified by China's growing power, its unfair trade practices with the EU or perceived security threats. Whilst the narratives were not predetermined, they coalesced into six recurring themes, which will be detailed in the subsequent section.

These narratives were then converted into codes for a software-assisted text analysis to quantify the prevalence of each argument across the different OSA instruments. The software used for the quantitative analysis was Dedoose, a web-based application designed specifically for rigorous mixed-methods research. The political texts analysed consisted of speeches and press releases from the three primary EU institutions: the European Parliament, the European Commission and the European Council. The media documents comprised a compilation of news articles mentioning China in connection with one or more of the instruments examined. The same criteria were applied to select political texts from the press corners of each EU institution.

For the media analysis, the five most influential outlets in Europe since at least 2020 were selected, based on the annual EU Media Poll conducted by Savanta (BCW, 2023)1: Politico, The Economist, Financial Times, Reuters and Euractiv. Each document was categorised according to four descriptors: type of source (EU institution or media outlet), specific instrument and year of publication. This process yielded a balanced dataset across the different instruments, although the European Commission and Politico emerged as the most prolific sources within their respective categories.

Data Description

The dataset used for the software-enabled text analysis comprises 810 documents published between 2010 and April 2024. This period was marked by a notable shift in discourse on China amongst European leaders and media outlets, with the various codes employed aiming to capture the essence of this change. Adopting the perspective that crises act as catalysts (Brecher and Yehuda, 1985), the timeframe begins in the immediate aftermath of the 2010 Eurozone debt crisis, which heightened China's perceived role as a critical economic player in Europe and underscored the need for the European Union to broaden its trade relations. It concludes with the post-COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2023), which exposed the risks of overdependence on external actors. Before this period, Chinese investment in Europe and its role in global economic governance were relatively minor (Casaburi, 2017, p. 43). As previously noted, the EU–China relationship was primarily characterised by economic opportunism during this earlier phase (Brown, 2018; Jing, 2018).

This timeframe also provides adequate scope to capture significant changes in European perceptions of China, particularly during key moments such as the transition in Chinese leadership in 2012 and the subsequent shift in foreign trade policy under Xi Jinping. This shift moved away from Deng Xiaoping's policy of ‘keeping a low profile and biding time’ (韜光養晦、有所作為) and the pragmatic philosophy of ‘it doesn't matter if a cat is black or white as long as it catches mice’. It also includes the official launch of the BRI in September 2013 and the period of substantial growth in Chinese inward FDI in Europe. Whilst these boundaries are inherently fluid, this 14-year timeframe effectively captures the key developments in EU–China trade relations, which have contributed to the increasing politicisation and securitisation of trade policy.

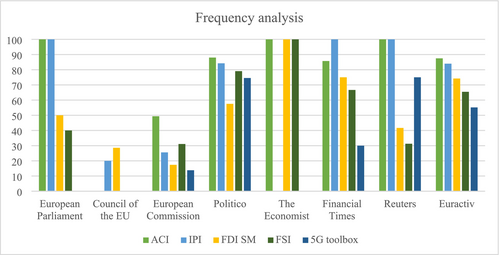

To assess the relevance of China in the communicative discourse surrounding the OSA instruments, particularly in comparison with other external factors identified in the literature, Graph 1 illustrates the frequency with which China appears in general discussions about the instruments. Specifically, it shows the percentage of documents mentioning both ‘China’ and one of the instruments, relative to those mentioning only the instrument, across media outlets and EU institutions. As previously established, quantifying the relative importance of China compared to other countries, entities or issues in driving the shift in EU trade policy presents a methodological challenge. Importantly, this analysis distinguishes between the legitimisation and the application of the TDIs. Whilst previous research has highlighted the utility of these instruments in addressing issues related to Russia and US tariffs on European imports or Trump's challenge to the World Trade Organization (Hopewell, 2021), this article focuses on the role of China in their legitimisation.

The findings indicate that although the instruments can be applied broadly and impartially to address various external factors, China has been a key factor in the legitimisation narratives developed by EU institutions. In fact, China is mentioned in more than 50% of the documents that reference one of the instruments, with the notable exceptions of the Commission (excluding the ACI) and the Council. This discrepancy could be attributed to the fact that Russia is predominantly perceived as a security threat rather than a trade threat, whilst EU trade policy towards the United States has been marked by greater internal discord, especially in response to Trump's attacks on the rules-based trading system and Biden's geopolitical pressure on the EU, exemplified by the Inflation Reduction Act (Herranz-Surrallés et al., 2024). Although both Russia and the United States have served as external drivers of the EU's shift towards the securitisation of trade policy, only China has provided the necessary institutional and popular unity to justify and legitimise the adoption of these instruments.

3 Analysis and Discussion

In-Depth Analysis

Each of the narratives identified through the inductive analysis of the documents is informed by existing academic literature that links the EU's trade agenda with China and illustrate a specific representation of China as ‘other’. The arguments appearing in the data that connect the instruments to each narrative are illustrated through quotes extracted from the dataset. Notably, China is invoked in support of both increased liberalisation – such as during negotiations for the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment – and trade protection, demonstrating how discourse evolves and adapts to shifting political goals and contexts.

In practical terms, EU trade policy discourse is used strategically by various actors to maximise their preferences (Schimmelfennig, 2001; Van den Hoven, 2004; Siles-Brügge 2011). This instrumental use of discourse underscores the role of narratives in shaping policy outcomes. The primary narratives identified through the in-depth analysis of the dataset are the following:

| Narrative | Explanative quote from the dataset |

|---|---|

| China unfairness |

‘When China gives subsidies to companies active on our Single Market, that amounts to an unfair advantage. Our new Foreign Subsidies Regulation is designed to address this - and we won't hesitate to open investigations if we consider that markets are being distorted in this way.’ Commission VP Vestager, Cleantech for Europe Summit, 25/01/2023. The European Commission considers TDIs as the cornerstone of European trade policy, to fight ‘unfair trade’. This relates to the notion of ‘free but fair’ trade (Mathieu and Weinblum, 2013). |

| China's power |

‘Brussels has been strengthening its economic security arsenal to face off Beijing's growing geoeconomic ambitions – from investment screening to measures countering trade bullying. While not intended to do that, these defensive measures signal a change of tone in the EU, and they make a decoupling scenario more plausible.’ Encompass, ‘The cost of Non-China: Reading the tea leaves’, 25/10/2022. EU policy-makers believe that ‘the balance of challenges and opportunities presented by China has shifted’ as ‘China's economic power and political influence have grown with unprecedented scale and speed, reflecting its ambitions to become a leading global power’ (EC, 2019). |

| China threat |

‘Similarly, efforts must be strengthened to limit Chinese investments in strategic sectors and infrastructure in Europe. Consequently, the Union's institutions must put in place a robust, mandatory FDI screening mechanism in place of their current, largely voluntary approach.’ Euractiv, ‘Europe cannot sleepwalk into another crisis’, 16/01/2023. This narrative is ‘based on the ontological criticism of the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP)'s authoritarian regime that is used to cast a shadow of suspicion over the conduct of Chinese companies, associations and citizens, as well as their European partners’ (Rogelja and Tsimonis, 2020, p. 104). |

| China as a justification |

‘So with our new instruments, like the International Procurement Instrument and the Regulation on foreign subsidies, we will have a new foundation on how to approach China.’ President von der Leyen, European Council, 21 October 2022. This narrative is understood as an empty signifier, to encompass all the arguments that link China to the TDIs and the ‘open strategic autonomy’ narrative, without going into any specific causality. Instead, China per se is used as a justification. |

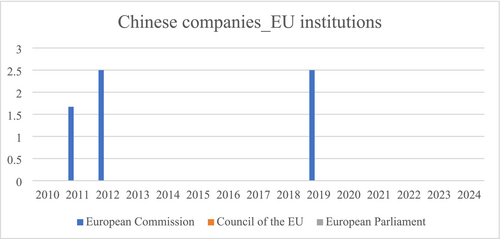

| Chinese companies, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and state-controlled enterprises (SCEs) |

‘While the rules are country- neutral, the regulation is a clear response to China's strategy of using state-owned enterprises to acquire key EU technology.’ Politico, ‘EU ambassadors approve investment screening law’, 05/12/2018. EU policy-makers and public are concerned about the rise of Chinese companies as foreign investors and competitors in procurement markets, who backed by the Chinese state can squeeze market opportunities even more for otherwise-competitive European producers (Erixon et al., 2021). |

| Chinese coercion |

‘Beijing's whimsical trade bans are the exact type of behaviour that Brussels is trying to deter with its planned anti-coercion instrument.’ Politico, ‘Morning Trade: Clarifying CETA – Sewage spills – Foreign investment’, 02/09/2022. China's economic coercive tactics ‘have become more sophisticated over time, and often a combination of different methods has been used to amplify the impact’, including trade restrictions, boycotts, administrative discrimination, investment and tourism restrictions and threats (Szczepanski, 2022). This is seen to undermine the European single market and warrant the need for TDIs. |

Text Software Analysis

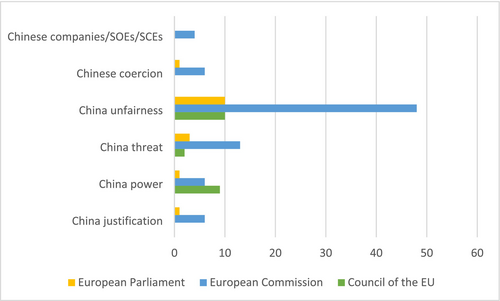

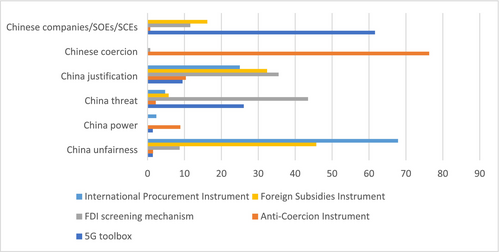

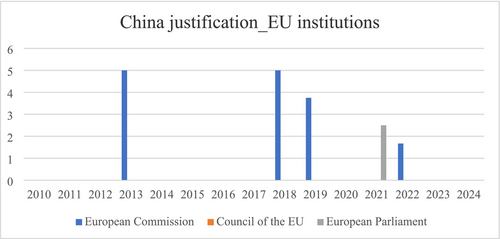

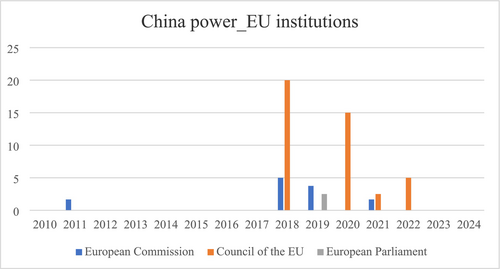

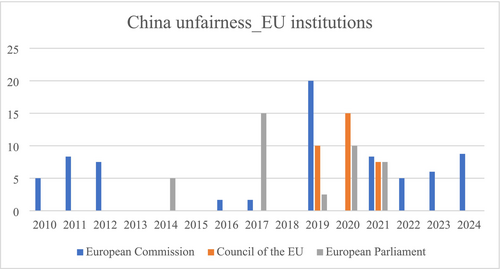

The six narratives were converted into codes for the software-enabled analysis. This process yielded 760 excerpts, whilst 209 documents showed no connection between the instruments and China – that is, both were mentioned, but without any portrayal of a relationship between them. Amongst EU institutions, the most frequently used narrative was that of unfairness, followed by China's power, which was particularly prominent in communications from the Council (Graph 2).

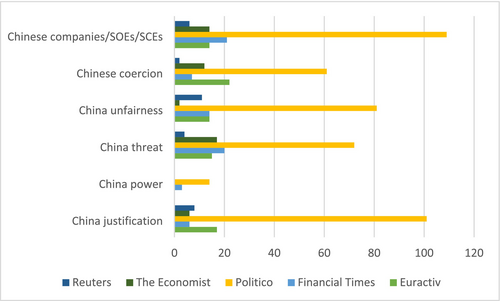

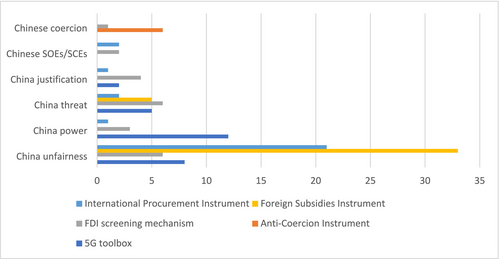

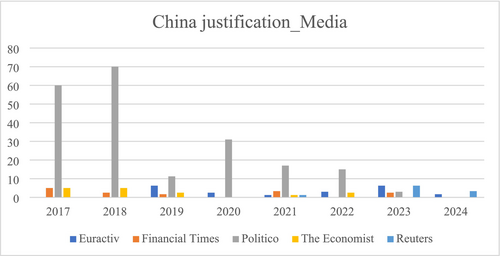

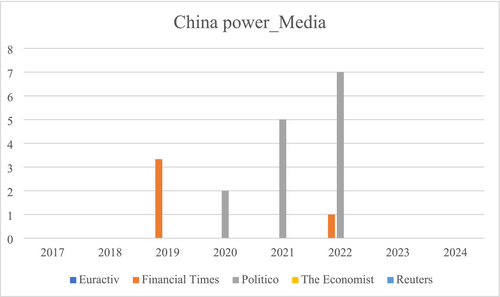

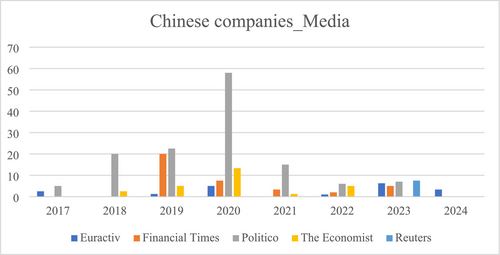

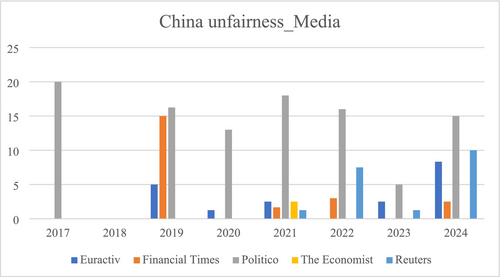

Across the media outlets analysed, China was uniformly cited as a justification for the TDIs (Graph 3). Notably, in specific instances, high-profile issues – such as China's economic coercion against Lithuania in 2021 or the potential dominance of a Chinese company in the EU's 5G networks – were employed as symbolic examples to reinforce specific narratives. The fact that these were real events made them more tangible and easier to capture public attention and imagination. The narrative surrounding Chinese companies, particularly Huawei and ZTE, is rooted in concerns over the close ties between China's state-business elites and the Chinese Communist Party, as well as the Chinese government's control over transnational corporations, many of which are (or were formerly) SOEs (De Graaff, 2020).

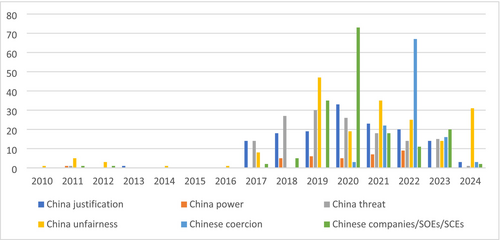

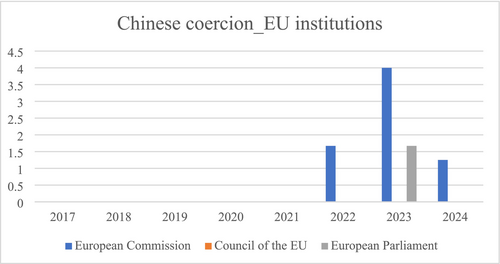

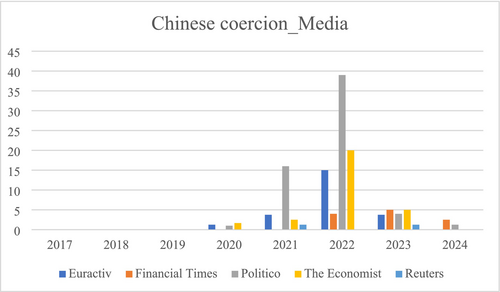

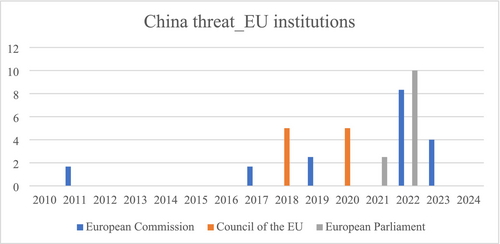

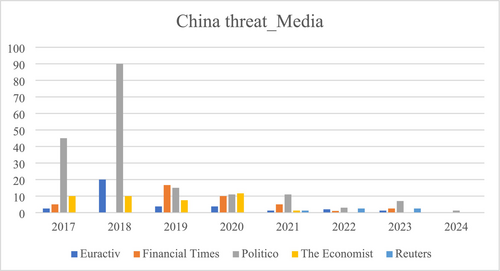

Both the Lithuania incident and the Huawei case were instrumentalised to advocate for the introduction of specific instruments – the 5G toolbox and the ACI – by illustrating how these mechanisms would function in practice. These cases captured public interest at critical moments, helped to popularise the instruments and garnered public support (Graph 4). Consequently, the instruments gained the necessary momentum to be negotiated and approved by EU institutions, thereby advancing the shift in EU trade policy. This also helped to mitigate dissent from those concerned about a drift towards protectionism, the potential erosion of EU values of free trade and openness and the risk of Chinese retaliation. This explains why the ‘Chinese companies’ narrative emerged as the most prevalent, followed by the ‘China threat’ and unfairness narratives.

The temporal evolution of the use of each narrative in media discourse, as shown by each determinant (Graph 4), highlights how China's role as a justification or target for the OSA toolbox became particularly prominent after 2017, with a notable spike in 2013, shortly after Xi Jinping's accession to power. This spike coincides with the increased prevalence of the ‘China power’ and ‘China threat’ narratives. As China's global influence grew and its behaviour became more assertive, it was increasingly perceived as antagonistic to the EU's values and norms of global governance, thereby positioning it as a systemic threat to the neoliberal international order.

From that point onward, China was progressively used to legitimise the EU's strategic reorientation and re-evaluation of its trade policy. This ultimately led to the development of new trade protection instruments aimed at safeguarding the European Union from actors perceived as not ‘playing by the rules’ (Erixon et al., 2021). When breaking down the temporal evolution by institutional and media discourse (see Appendix A, A1-A12), the ‘dual process of legitimation’ mentioned in The Evolution of the EU's Trade Discourse section is evident, showing that these two actors alternatively act as discourse entrepreneurs to shape the perception of China amongst the European public. In some cases, it is EU institutions who promote a specific narrative that is than taken up and amplified by the media, as is the case with ‘unfairness’, ‘companies’, ‘justification’ and ‘power’, whilst in other cases, it is the media who promotes a narrative that is ultimately embraced by EU institutions as it becomes mainstream, as exemplified by the ‘China threat’ narrative (Rogelja and Tsimonis, 2020), or the ‘coercion’ narrative.

The discourse surrounding China's unfair economic and trade relationship with the European Union is not new and predates the emergence of the ‘China threat’ narrative. Since its resurgence after 2017, and particularly following the publication of the 2019 EU-China Strategic Outlook, both narratives have increasingly converged around the securitisation of Chinese investment in Europe, inevitably tied to the broader geopolitical landscape. Concerns about China's lack of market openness and incomplete economic liberalisation were already present in Europe before its accession to the WTO. However, during this earlier period, there was observable progress, and the prevailing narrative focused on the EU's willingness to ‘work with China to help it with its internal reforms’, as reflected in the 2006 European Parliament Communication ‘EU-China: Closer Partners, Growing Responsibilities’ (Brown, 2018). This narrative shifted dramatically with Xi Jinping's rise to power, as Deng Xiaoping's doctrine of ‘reform and opening up’ was replaced by greater assertiveness both domestically and internationally, with Xi proving to be ‘a very anti-liberal leader’, who chose to ‘suppress rather than embrace reforms’ (Shambaugh, 2016).

The first spike in the ‘unfairness’ narrative is reminiscent of earlier concerns about China's trade practices but occurred within a context of ongoing reform and gradual liberalisation. In contrast, the second spike, observed after 2017, is qualitatively different, reflecting a perceived reform deadlock and China's growing economic assertiveness. This shift contributed to the abrupt rise in the popularity of the ‘China threat’ narrative in media discourse, which has maintained a steady presence since 2017 (Graph 4). The ‘China threat’ narrative encompasses both economic and political dimensions, advocating for the securitisation of China's presence in Europe. It portrays China's actions in Europe as primarily political, driven by a distorted perception of Chinese economic activities abroad – such as the BRI – and a view that frames pluralism as weakness and internal dissent as disagreement (Rogelja and Tsimonis, 2020).

Overall, the widespread presence of China in the communicative discourse surrounding TDIs – particularly in relation to China's status as a global power that rivals the European Union and poses a systemic challenge – demonstrates how China has been instrumentalised to strategically justify and legitimise the TDIs, especially since 2017.

Discursive Framing Analysis

An analysis of the interactions between codes for media outlets and EU institutions uncovers the discursive framing by each institution or media outlet with relation to each instrument and exposes various patterns. This is especially evident in the media outlet results (Graph 5), which clearly demonstrate that each narrative has been predominantly tied to specific instruments. For example, the narratives of ‘China as a threat’ and ‘Chinese companies’ – either directly as a justification for the 5G toolbox or indirectly as a threat to the 5G network due to connections with the Chinese government – were the most frequently cited reasons for adopting the 5G toolbox. Similarly, China's use of economic coercion was closely linked to the ACI. The narratives of ‘China as a justification’ and, particularly, ‘China as a threat’ were central to justifying the FDI screening mechanism, reflecting the growing perception amongst EU stakeholders that Chinese investment poses a threat. Meanwhile, narratives emphasizing the unfairness of Europe's economic and trade relationship with China were most frequently used to support the FSI and the IPI. Specifically, media coverage of the IPI highlighted the closed nature of China's procurement market, whilst references to the FSI underscored China's financial support for its companies, particularly SOEs and state-controlled enterprises (SCEs), as key sources of this perceived unfairness.

Overall, Chinese investment in Europe, especially in strategic sectors like 5G networks, has been framed as a security threat, whilst trade with China in the areas of procurement and subsidies has been depicted as unfair, thereby justifying the introduction of instruments aimed at addressing these imbalances.

Interestingly, the analysis also reveals that media discourse has presented a selective and somewhat unrepresentative sample of elite rhetoric, shaping public perceptions of Chinese investment and trade by deliberately emphasising particular narratives. Specifically, the media has tended to highlight the ‘unfairness’ narrative in discussions of trade, whilst stressing the ‘threat’ narrative in the context of investment. Chinese investment is primarily portrayed as a multifaceted threat, encompassing diverging standards, aggressive market acquisition – particularly in the post-pandemic context –, wolf warrior diplomacy, and investment in strategic sectors such as high technology. Conversely, trade with China is framed as unfair from the EU's perspective, due to perceived issues such as a lack of openness, an uneven playing field and significant state aid to Chinese firms. Across all instruments, the more neutral ‘China as a justification’ narrative appears consistently.

Overall, the analysis of these correlations demonstrates that China has been portrayed from different angles, resulting in a heterogeneous narrative in which specific perspectives are strategically emphasized to justify the various TDIs. Additionally, it shows that media framing of policy-makers' rhetoric has led to a shift away from the predominance of the ‘unfairness’ narrative towards a more diversified narrative that increasingly highlights ‘China as a threat’, its coercive practices and concerns about government control over Chinese companies.

Regarding EU institutions (Graph 6), the most prevalent narrative over the years has been the unfairness in the EU's economic relationship with China. This narrative has been most frequently applied to justify the FSI and the IPI. Consequently, trade – particularly in the contexts of procurement and subsidies – is portrayed as unfair, with these instruments framed as necessary measures to address the imbalance attributed to China. In contrast to the media, the ‘China justification’ narrative is less prominent in the discourse of EU institutions, whilst the justification for the 5G toolbox is primarily linked to China's growing power.

Additionally, the analysis reveals that following the Commission's initiation of the first investigations under the FSI in 2023, the ‘Chinese companies’ narrative gained prominence, as these companies were disproportionately represented in the consortia under investigation. Meanwhile, the initial IPI investigations have continued to reinforce the dominance of the unfairness narrative. Notably, the ‘China threat’ narrative, which was almost absent in institutional discourse before 2022 (except within the European Parliament), began to gain traction as EU institutions started promoting ‘de-risking’ and Economic Security strategies. This narrative has occasionally supplanted the unfairness narrative, whilst at other times it has complemented it.

In summary, since 2023, the TDIs have become increasingly integrated into broader strategic frameworks, moving beyond their original focus on ‘strategic autonomy.’ This shift reflects a deepening trend towards the geopoliticisation of trade within the European Union (Meunier and Nicolaidis, 2019).

Conclusion

Despite repeated claims by EU leaders that the instruments within the OSA toolbox are ‘country agnostic’ (EC, 2023b), the findings of this article demonstrate that China has been instrumentalised in both media and policy discourses, albeit in different ways, as a means to justify the necessity and existence of these instruments. This instrumentalisation has been carried out in a highly strategic and targeted manner, distinct from references to the United States or Russia, which only appear in the ‘justification’ or ‘power’ narratives within the context of great-power competition and the increasing ‘geopoliticisation’ of trade. EU institutions, at least until 2023, predominantly focused on the unfairness narrative across all instruments, displaying less narrative heterogeneity compared to the media. In contrast, media outlets made a more varied and selective use of the identified narratives, deploying them strategically to justify specific instruments.

More specifically, the analysis provides substantial evidence that the discourse framing China as a justification for trade protection instruments is highly heterogeneous, reflecting the diverse purposes of each instrument. The media, in particular, has promoted two distinct narratives regarding China: one portraying it as a threat in the context of investment, and another framing it as a source of unfairness in trade. This dual portrayal reinforces the perception of China as a competitor and political rival rather than an economic partner, fostering a vision of China as a ‘threatening other.’ Consequently, this narrative encourages EU citizens to view confrontation with China on trade- and non-trade-related issues as more justified. This aligns with the broader trend towards the ‘securitisation’ of Chinese investment in Europe – a trend that, rather than reflecting actual threats, disproportionately highlights Chinese FDI relative to its actual size and impact.

More broadly, these findings raise the question of how far the European Union can continue employing protectionist measures before its normative identity as a liberal, normative power is fundamentally challenged. Meunier (2022) argues that whilst the European Union continues to advocate for economic openness and positions itself as a defender of multilateralism, the use of unilateral trade instruments signals a significant shift towards a more assertive and less open trade policy. Even though these instruments are justified by the need to safeguard multilateralism and respond to a world increasingly marked by tit-for-tat strategies and divide-and-rule tactics, the European Union has, in effect, adopted more protectionist measures to prevent coercion and exploitation. This raises important questions about the EU's evolving identity – whether the emergence of a ‘Geopolitical’ or ‘Geoeconomic Power Europe’ is replacing ‘Normative Power Europe’ (Haroche, 2024; Orbie, 2021) or whether the two can coexist and potentially reinforce one another, rather than being in conflict.

There are additional concerns that the OSA instruments could be co-opted for purely protectionist purposes, or at the very least, that they might dangerously shift the EU's focus from trade openness towards trade defence (Hackenbroich and Zerka, 2021). This could lead to an increasingly bifurcated trade regime, with continued openness towards allies but heightened assertiveness and greater reliance on autonomous tools against perceived rivals (Schmitz and Seidl, 2023). Therefore, future research should explore the implications of the OSA instruments, the Economic Security Strategy, and the ‘de-risking’ strategy on the EU's normative power. Additionally, as the implementation of the OSA toolbox progresses, it will be crucial to analyse its impact on Chinese investment in the European Union and the broader EU–China trade relationship. Finally, further study should examine whether China has played a central role in the EU's co-ordinative discourse and, consequently, whether it has influenced the enactment and specific configuration of the TDIs.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the editors of Journal of Common Market Studies and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that allowed improving the article. I would also like to thank Prof. Jacint Jordana and Prof. Luis Simón for their guidance and help throughout the research and review process that led to this publication. This research was supported by a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (SINATRA project – Grant Agreement No. 101045227).

APPENDIX A

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr. Laia Comerma, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1 National media outlets were left out as the purpose of this analysis was to uncover pan-European discourse, parallel to that of EU institutions. Any potential geographical divergence among EU member states should be the focus of further analysis.