For the Times They Are A-Changin': Towards a ‘Homeland Economics’ Paradigm of the European Union?

Abstract

There is an ongoing academic debate on whether geopolitical aspirations are reshaping the paradigm of the EU's neoliberal industrial and trade policy. The scrutiny has intensified with China's new economic power, the Trump and Biden administrations, Covid-19 and Russia's invasion of Ukraine. However, the theory of paradigm changes expects that the institutionalisation of a new paradigm requires an evolution, based on a series of mechanisms slowly eroding the legitimacy of the existing paradigm. This article investigates this process by formulating four causal chains, representing different scenarios for a new strategic paradigm in the EU's industrial and trade policy. Through the method of process tracing, it finds that the foundations for a new strategic paradigm were made under the Juncker Commission. Here, France formulated a new policy agenda, which was successfully pushed into EU economic policy-making. Since then, the EU has moved towards a ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm, though with important reservations.

Introduction

At Commission President Ursula von der Leyen's State of the Union address in 2023, applause and cheers erupted as she announced an anti-dumping investigation into Chinese electric cars. This approval was difficult to imagine 10 years ago and therefore marked a possible new paradigm in the EU's industrial and trade policy (see presentation of rivalising paradigms in Annex S7).

The shift can be seen in the context of the liberal world order being challenged by geopolitical great power rivalries, which are fought with economic means (Fjäder, 2018). The EU also has ambitions to increase economic resilience in the face of geopolitical pressure (Gehrke, 2022; Haroche, 2023; Olsen, 2022). Public management of the EU's economic interdependence, however, presupposes a showdown with its neoliberal industrial and trade policy, involving market-intervening instruments and resilience objectives in strategic areas and sectors. However, a more refined and granular approach is lacking for analysing these developments. We wish to contribute to the debate with exactly that. In this context, we show that the changes in the EU's industrial and trade policy are a more lengthy and gradual process than is often apparent from both the scholarly literature and the media. This is done on the basis of a theoretical framework that we have adapted for this purpose, allowing the reader to gain an understanding as to why there is often an inherent inertia in political changes in the EU.

This analysis is based on Oliver and Pemberton's (2004) paradigm evolution theory, which considers a longer evolutionary process to be a prerequisite for a paradigm shift (see models for paradigm evolution in Annexes S8 and S9). Originally, Thomas Kuhn's concept of paradigm in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Kuhn, 1997 [1962]) was mainly meant for use in the natural sciences. However, in practice, it has first and foremost been influential in social sciences such as political science. Oliver and Pemberton's theory is just one of many examples thereof. The process in their theory implies a loss of legitimacy for the existing paradigm, and that policy entrepreneurs formulate and mobilise support for an alternative, that is, the ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm of the EU. The evolutionary process is examined through process tracing, where all mechanisms in the paradigm evolution must be identified in order to conclude whether a paradigm shift is taking place (Beach and Brun Pedersen, 2012). In this connection, we set up four causal chains, which constitute four scenarios for an economic policy paradigm evolution; these are tested on two legislative proposals – the industrial policy proposal Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) and the trade policy proposal Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) (see list of acronyms in Annex S6).

We examine the evolution process in three sections that address it from the first losses of legitimacy of the neoliberal paradigm under the Juncker Commission to the formulations and negotiations on CRMA and ACI. We demonstrate how paradigm changes are actually taking place in the direction of the establishment of a ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm in the EU in the industrial and trade policy field. However, these changes are only occurring after a lengthy policy process involving changes in the coalition structure in the EU after Brexit and activities of outspoken policy entrepreneurs.

I Rival Paradigms

During the economic eurosclerosis of the 1980s, two economic projects emerged that competed to become the new industrial and trade policy paradigm (van Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 89). French decision-makers and business promoted a neo-mercantilist policy, which, through close state–market relations, actively supported national champions and sectors that needed to grow in a European market (Calmfors et al., 2008, p. 106). On the other hand, a British-led neoliberal camp wanted to strengthen competitiveness through a common European market. At the same time, it had to be scaled up on a global level through a liberal trade policy to promote competition and economic efficiency (van Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 89). Many European export companies that hoped to operate on both a European and global level supported the neoliberal paradigm (van Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 110). In the debate, Germany placed itself, with its ordoliberal economic model, between the neoliberal and the French position (Nedergaard and Snaith, 2015). The controversy ended with a neoliberal paradigm in which Anglo-Saxon free market competition was combined with German free trade-oriented ordoliberalism (van Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 96). Afterwards, the neoliberal project was therefore institutionalised as the paradigm for the EU's market structuring (van Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 91).

The development of the EU's industrial and trade policy paradigms has taken place in the context of the various rounds of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations and, in the last decades, the oscillating adherence to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules amongst an increasing number of states. Not least China's accession to WTO in 2001 has influenced the EU's development of its trade policy paradigms because it has strongly increased China's exports and competitiveness, which has put a number of economic sectors in the EU under pressure (Eliasson and Garcia-Duran, 2023; Velut et al., 2022). This is an important backdrop to the pressure against the neoliberal paradigm.

Originally, the neoliberal paradigm that arose implies a horizontal industrial policy, where public interventions address general market failures without preferences or differentiation of sectors and companies (Calmfors et al., 2008, p. 106). Although there are examples of active and sector-based EU policies such as in the agricultural and regional spheres, they have been seen as exceptions to the rule in the name of securing social and regional balances. The EU's trade policy has also been governed by the neoliberal paradigm since the 1980s. Although there have again been exceptions with protectionist policy, trade policy has fundamentally promoted global trade liberalisation through multilateral rules with a view to markets promoting efficiency through increased global competition and comparative advantages (Nedergaard, 2009).

Today, however, we claim that a new economic paradigm is being implemented, which The Economist calls ‘Homeland Economics’. This implies that governments want to reduce foreign policy risks using interventionist instruments (The Economist, 2023). Since the potential new policy paradigm is closely linked to foreign policy, we briefly shed light below on the development of the EU's foreign policy in relation to industrial and trade policy.

The understanding of economic dependence can be divided into two different foreign policy approaches (Gehrke, 2022). A liberal approach corresponds to the neoliberal paradigm in industrial and trade policy and is reflected in the quotation ‘Europe has nothing to fear from China's phenomenal growth’ from former trade commissioner Peter Mandelson (Gehrke, 2022, p. 64). The liberal understanding of interdependence has resulted in a European ‘Wandel durch Handel’ foreign policy, which coexists with an industrial and trade policy with the desire to promote global trade.

Conversely, a realistic approach to interdependence can be translated into geo-economic foreign policy. This corresponds to the ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm, and it implies that states weaponise economic dependencies to achieve geopolitical objectives. Geo-economic foreign policy therefore unfolds through economic alliances and economic conflicts between states. The defensive and offensive management of the economy involves state intervention and restrictions on global trade as well as the selection of support for certain strategic sectors and companies.

However, the ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm is different from economic nationalism (Schild and Schmidt, 2023) because of its new strategic elements. At the same time, it can be considered a concrete expression of a trade-as-foreign policy approach (De Ville and Siles-Brügge, 2018) under the new strategic circumstances. The advantage of using the policy paradigm concept is that it plays together with a wider theoretical debate in political science about the nature and extent of policy change (cf. also Oliver and Pemberton, 2004). By exploiting the paradigm concept, we can potentially use the analysis of CRMA and ACI as a contribution to a better understanding of the evolution of policy paradigms.

Clearly, a change is seen in the EU in the industrial and trade policy area, where decision-makers observe a need to increase resilience towards states such as China, Russia and even the United States, whilst the former way of thinking is viewed as naive and vulnerable (Fjäder, 2018, p. 28; Gehrke, 2022, pp. 66–67; Haroche, 2023, p. 5). The ambition is presented via the formulation of geo-economic instruments such as ACI, which was launched under the concept of ‘open strategic autonomy’ (Gehrke, 2022, p. 68; Olsen, 2022, p. 6). The open as well as autonomous element, however, illustrates a tension in the new concept. It depends on the possibility of exercising geo-economic foreign policy via the state–market relationship, since the economy, as opposed to military means, is placed under the auspices of the private market. The fulfilment of the EU's geo-economic ambitions therefore requires the support of institutional and private players in the economic field (Olsen, 2022, p. 12). However, this is not a given, as the EU's industrial and trade policy has proven resistant to change (De Ville and Orbie, 2011).

There is also no agreement in the literature on the character of the new paradigm. Jacobs et al. (2023) find that DG Trade manages to incorporate rhetoric about strategic autonomy from Covid-19 into trade policy without real policy change. On the contrary, Schmitz and Seidl (2023) deduce that open strategic autonomy constitutes a new industrial and trade policy compromise, such as the one formulated in the 1980s (Schmitz and Seidl, 2023, p. 849). Who is right?

The 2021 updating of the EU's trade strategy was divided fairly equally between promoting sustainability and labour in all trade agreements and other fora (a liberal foreign policy initiative) and securing greater economic resilience and strategic autonomy (a realist imprint). DG Trade continuously emphasised its preference for multilateralism (European Commission, 2021a). Only in 2023–2024 did some Commission officials begin changing their emphases, presenting rather different normative perspectives, best fitting geopolitical (realist) positions (e.g., Interview F' – interview transcripts are not available to readers in Annex S1).

Bora and Schramm (2023) have established that over recent years, there has been a growing French influence – especially after Brexit in 2020 – on the EU's fiscal policy, competition policy and industrial defence policy prompted by national, bilateral and external factors. In addition, Di Carlo and Schmitz (2023) point to an industrial policy shift in the EU with France as the spearhead. They analyse the industrial policy initiatives from the Commission since the mid-2010s, which are characterised by being sector-specific and interventionist. They then explain the underlying timing of industrial policy change with functional, cultured and political spillover. In addition, McNamara (2024) believes that the EU is beginning to pursue an activist industrial policy that breaks with the neoliberal model. Again, a conflict between the open and the autonomous is pointed out, where a post-liberal coalition of strategically and socially oriented actors is critical of the establishment of a new market activism and interventionism (McNamara, 2024, p. 2382).

From the literature, there is still uncertainty about the exact balance between openness and autonomy regarding the specific policy, but industrial and trade policy ambitions have the potential to constitute a new paradigm. Thus, both Schmitz and Seidl (2023, p. 849) and McNamara (2024, p. 2382) call for a closer look at how coalition formation and conflict play out in actual policy-making. Against this background, we will analyse the possible development of a new strategic policy paradigm called ‘Homeland Economics’.

II Theory

In order to explore whether the EU's change of industrial policy and trade policy can be interpreted as a translation into a new policy paradigm, we will use Oliver and Pemberton's model to investigate whether a paradigm evolution has taken place. As indicated above, the aim of introducing the paradigm concept in the analysis of ACI and CRMA is potentially to make the case analyses general examples of how and when policies change. This is the advantage of applying Oliver and Pemberton's general paradigm evolution theory.

The analysis has a theoretical starting point in the phenomenon of policy subsystems, as the possibility of the ambitions being translated into policy is assumed to depend on the subsystems in which the initiatives are to be institutionalised (cf. Rozbicka, 2013, p. 843). In this connection, an examination is conducted into whether ambitions at a political macro level are translated at the meso level in the form of the subsystems within the policy area. This focus is central because of the various policy modes within different subsystems, where decision-making procedures and actor compositions vary (Wallace and Reh, 2020, p. 92).

The paradigm evolution theory is based on Hall's conceptualisation of policy changes, which divides changes in policy into first-, second- and third-order variations. First-order changes adjust existing instruments. The second-order changes are changes in instruments, but not the basic objectives and their prioritisation. Third-order changes involve the introduction of new instruments, objectives or a new prioritisation of objectives. They take place on the basis of new understandings of public problems and appropriate solutions amongst decision-makers (Hall, 1993, pp. 279–282).

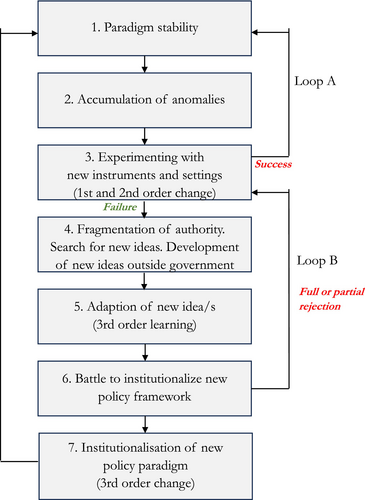

Oliver and Pemberton (2004) argue that an institutionalisation of third-order changes and thus a new policy paradigm presupposes more than new perceptions. Thus, these changes require a long and conflict-filled process, where policy entrepreneurs must formulate new ideas and secure institutionalisation by mobilising actor support within the subsystem. The process can result in a complete paradigm shift or loss, but also in a comprehensive second-order change, where the variations are incorporated as a subcomponent in the prevailing paradigm (Oliver and Pemberton, 2004, p. 419). Oliver and Pemberton encapsulate this process in a seven-phase model that structures the mechanisms behind the paradigm shift. It is illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: Oliver and Pemberton (2004, p. 420).

In the first phase, there is paradigm stability, where first- and second-order policy changes can occur. In the second phase, there is an accumulation of anomalies, which are outside the scope of the existing paradigm. In the third stage, decision-makers address the anomalies with policy experiments in the form of first- and second-order changes. If the anomalies are managed (Success in Figure 1), the legitimacy of the existing paradigm will be re-established, after which the evolution process will be stopped (Loop A in Figure 1).

If the policy experiments fail, Phase 4 begins (Failure in Figure 1), where the legitimacy of the paradigm is fragmented. This can lead to two scenarios. One is that the paradigm continues without legitimacy if an alternative policy paradigm is not formulated. In another, the development of ideas towards third-order changes begins outside of government. If the second scenario takes place and policy entrepreneurs can mobilise a coalition for the third-order changes, the alternative policy paradigm is adopted on an institutional agenda in Phase 5. In Phase 6, the institutionalisation battle takes place on concrete policy proposals within the subsystem. Here, third-order ideas can be opposed and fail in whole or in part. A partial loss involves Loop B (Phase 6) back to Phase 3. If the new reduced third-order changes succeed in finding a suitable solution to the anomalies, the old paradigm will exist in a moderated version with the new alternative paradigm as a subcomponent. Phase 6 therefore involves the formulation and decision-making phase of a policy process as described by Howlett and Giest (2013, p. 17). If it succeeds in institutionalising the third-order changes, the alternative paradigm will be established as the new one in Phase 7. In order for paradigm evolution to be demonstrated, it is therefore crucial that the above mechanisms and phases can be identified.

III Methodology

Through process tracing, we will examine whether industrial and trade policy has gone through a paradigm evolution, where the new initiatives are the result of and the beginning of a new paradigm. The actual differentiation between the two paradigms is based on the operationalisation of instruments and objectives in a possible policy development shown in Table 1.

| Objectives | Industrial policy instruments | Trade policy instruments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm | Economic resilience | Active industrial policy, where strategic areas are strengthened through beneficial (1) financial or (2) regulatory instruments | Defensive and offensive instruments outside multilateral institutions and with sector specific diversification of trade agreements |

| Neoliberal paradigm | Economic efficiency | Horizontal industrial policy addressing externalities and market failures | Rule-based trade through multilateral organisations that remove market barriers |

It should be noted that differences in the objectives and instruments of the paradigms (as opposed to neo-mercantilism or economic nationalism) only apply to sectors that are strategically important. The decisive factor as to whether a paradigm is ‘Homeland Economics’ or neoliberal therefore depends on how objectives and instruments are prioritised when they cannot coexist. The prioritisation shows whether a ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm with a neoliberal subcomponent or a neoliberal paradigm with a ‘Homeland Economics’ subcomponent can be identified.

We have selected CRMA and ACI as cases to examine both an industrial and trade policy proposal, as this reflects McNamara's (2024) division of internally and externally directed market intervention instruments. In addition, the analysis of cases is important when we want to conduct process tracing. The choice of the policy initiatives has also been made since, unlike many other proposals, they had been finalised at the time of analysis. Finally, they have been selected as they have already received much focus (cf. Gehrke, 2022; Haroche, 2023; McNamara, 2024; Olsen, 2022; Seidl and Schmitz, 2023).

Process tracing is used as we examine whether the causal chain behind the paradigm evolution appears in the development of the proposals, with which it can be determined whether CRMA and ACI are the result of a new paradigm evolution. The theory-driven approach to process tracing constitutes a suitable research design, as the literature (Gehrke, 2022; Haroche, 2023; McNamara, 2024; Olsen, 2022; Seidl and Schmitz, 2023) has established a connection between anomalies and new policy instruments such as CRMA and ACI, but without a focus on whether the correlation is characterised by paradigm evolution.

The use of process tracing differs from its typical application, as the dependent variable – possibly a new paradigm – is not known (Beach and Brun Pedersen, 2012, p. 235). On the other hand, the end result itself (CRMA and ACI) is known, which is why the concept of process tracing can be used. The Y variable in the research is whether an alternative paradigm has been established, whilst the end result, which must exist in accordance with the method of process tracing, is constituted by CRMA and ACI.

Specifically, the paradigm evolution is examined by setting up four competing and comprehensive causal chains for the process behind CRMA and ACI, which constitute different paradigmatic scenarios for the correlation between anomalies and CRMA and ACI as policy outcomes.

- Causal Chain 1, Rhetoric and Policy Outlier: The neoliberal paradigm continues – with new rhetoric and individual policy outliers such as CRMA and ACI (Phases 1, 2 and 3 are not identified).

- Causal Chain 2, Early Paradigm Stage: The ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm is still in an early stage, where it cannot be concluded whether it leads to a change (Phase 4 is not identified/or Loop A is identified).

- Causal Chain 3, ‘Homeland Economics’ Component: The neoliberal paradigm continues, but ‘Homeland Economics’ first- and second-order objectives and instruments are incorporated into policy, as long as there is no compromise with liberal objectives and instruments (Loop B).

- Causal Chain 4, ‘Homeland Economics’ Paradigm: A new paradigm is established, but liberal first- and second-order objectives and instruments are incorporated into policy, as long as there is no compromise with strategic objectives and instruments (Phase 7 is identified).

The causal chains are developed based on the mechanisms in the seven phases of evolutionary theory and constitute a deterministic causal design where the scenarios are mutually exclusive. Below, we will describe the observable implications to confirm or disprove the causal chains. These are empirical examples of the necessary mechanisms in the theory, and the existence of them is central in process tracing. As mentioned below, the question of whether or not these causal chains exist relies on our careful categorisation and objective interpretation of the data: official documents and think tank reports, reports from the European Parliament and interviews (see list of reports and Policy Manifestos in Annex S5).

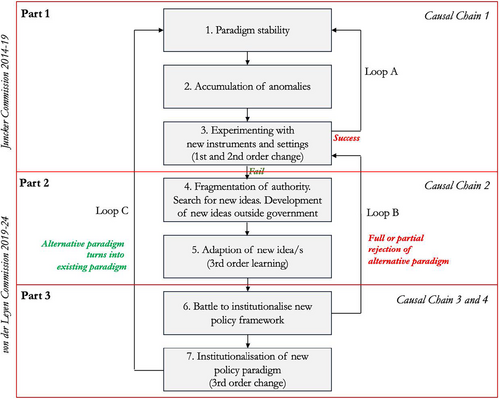

Figure 2 shows the three parts of the analysis. In the first part of the analysis, we investigate whether the first three phases of the paradigm evolution theory can be identified. In order to create analytical clarity, the focus is on the Juncker Commission in relation to whether anomalies arise and an attempt to answer this is made within the existing paradigm and whether they fail, thereby creating a slow delegitimisation of the neoliberal paradigm, on which a new paradigm can be developed. If the implications of failed policy experiments are observed, Causal Chain 1, Rhetoric and Policy Outlier, can be written off.

Source: Authors' own construction.

The second part examines Phase 4 in the form of legitimacy fragmentation and idea development of a new policy paradigm, as well as Phase 5, which deals with the presentation of third-order changes in the institutional agenda under the von der Leyen Commission. The observable implications are the existence of policy entrepreneurs, and that they establish initial coalitions behind an alternative paradigm. The two mechanisms must be identified for a new strategic (‘Homeland Economics’) paradigm evolution to continue, whereby Causal Chain 2, Early Paradigm Stage, can be written off.

The third part analyses Phase 6, examining the institutionalisation battle of the establishment of third order changes during the formal formulation and decision-making of CRMA and ACI (Howlett and Giest, 2013, p. 17). If the ‘Homeland Economics’ instruments are not prioritised above neoliberal elements – either by not making it into the proposals or being negotiated out, Causal Chain 3, ‘Homeland Economics’ Component, can be identified. A point of interest is whether a post-neoliberal coalition can be identified, as seen on a rhetorical level by Seidl and Schmitz (2023). If new strategic objectives and instruments form the priority in CRMA and ACI after the negotiation, Phase 7 will enter in effect, and Causal Chain 4, ‘Homeland Economics’ Paradigm, will be identified. Generally, it is assumed that different causal chains in industrial and trade policy due to varying policy subsystems can be a possible observation.

IV Data Collection

The data consist of document collection and interviews. The document collection has taken its starting point from the legislative proposals themselves and associated official documents, from which we have moved back into the underlying processes. In addition, reports from the European Parliamentary Research Service have been utilised, which give neutral information and an account of primary documents and research in the area, as they are used for policy work across the political groups. Official and primary documents are prioritised in order to maximise the validity and power of the statement. The empirical collection is centred on critical points with direct implications for the causal chains in the paradigm evolution.

Empirical data have also been obtained through interviews with people from the European Parliament, the Commission, member states and interest organisations. What is most important is that this data triangulation strengthens the validity of the data collection (see Annex S1). In our analysis, we are aware of the potential bias because most of the interviewees are Danish citizens.

V Analysis: Part 1 in Figure 2 – First Fragmentation (Phases 1–3)

In the first part of the analysis, the period under the Juncker Commission is examined in order to identify the first phases of the paradigm evolution. The section is structured according to critical points in the period.

When Juncker took office as Commission President in 2014, there was a consensus behind the neoliberal paradigm in industrial and trade policy. With this, the first phase regarding paradigm stability can be identified. Whilst the Brexit vote raised initial concerns that the EU's liberal principles would be challenged due to Britain's exit from the bloc (Cohen-Setton, 2016), the loss of legitimacy amongst EU decision-makers was limited. Brexit therefore did not lead to new policy experiments in industrial and trade policy, and no causal link can be identified between popular resistance to globalisation and the beginning of a new strategic paradigm evolution. However, Britain's withdrawal had an important later significance for paradigm development, as it shifted the coalition composition in the EU (Dagnis Jensen and Snaith, 2018, p. 257). Here, there was early concern from the Nordic side about a lack of future neoliberal leadership, whilst France considered it a new area of opportunity, which is dealt with further in the second part of the analysis.

The first anomaly that led to a loss of legitimacy amongst the EU's decision-makers was the first Trump administration's questioning of the liberal world order. Here, two events in particular were decisive for the initiation of Phases 3 and 4 in the paradigm evolution of the EU's industrial and trade policy. The Trump administration's first attack was marked by imposing steel and aluminium tariffs against the EU, amongst others (Harte, 2018). Based on the EU's explicit ambition to counter the attack on multilateral and rules-based trade within the neoliberal paradigm (Harte, 2018), the EU engaged in formal WTO processes (Demertzis and Fredriksson, 2018). This constitutes first-order changes in policy. This is because instruments that are available in multilateral institutions and the EU's work processes for handling trade disputes are being implemented. Therefore, the reaction marks the beginning of Phase 3, where decision-makers experiment with the existing policy toolbox to address an anomaly in the neoliberal paradigm.

However, the handling was not unequivocally successful. On the one hand, countermeasures imply the start of a trade war in which US tariffs remain in force for a long time. On the other, the conflict did not escalate further, as feared (Harte, 2018, p. 1). However, the event had two long-term effects on the legitimacy of the neoliberal paradigm. Whilst the United States was previously the EU's most important ally and strongest partner in the WTO, the EU now stands more alone in the protection of rules-based multilateral trade. At the same time, the incident shows how vulnerable the EU is to trade attacks, with which the event erodes legitimacy, but without alone bringing about Phase 4 of a paradigm evolution.

Shortly after the trade war with the United States, a new conflict arose that the neoliberal policy instruments were not developed to address. The background was that the United States withdrew from the multilateral nuclear agreement with Iran, whilst the EU chose to maintain the agreement. Consequently, the first Trump administration activated the controversial Helms–Burton Act, which sanctions foreign (including European) companies if they do not comply with American Iran sanctions (Immenkamp, 2018, p. 5). The EU responded by activating the previously not fully used blocking statute instrument, which prohibits European companies from complying with US sanctions (Reuters, 2018). Thus, Phase 3 can be identified, where an anomaly leads to policy experimentation. Since the instrument itself intervenes in companies and markets, it is already on the edge of the neoliberal paradigm. At the same time, it only constitutes a policy adjustment, which is why it continues to be characterised as a second-order change.

However, the second-order experiment failed, as the threat of losing access to the US market and dollar outweighed the possible interventions from the EU's blocking statute (Ribakova and Hilgenstock, 2020, p. 13). Thus, companies such as Airbus, Total and Siemens withdrew from Iran (Bayer, 2018). The implementation of the blocking statute therefore constitutes a significant loss of liberal legitimacy, where several actors lose faith that the neoliberal trade policy paradigm can address a confrontational world order, where third countries operate outside of the multilateral regimes, within which the EU's policy has been developed to act. The Trump administration thus constituted an overall anomaly for the EU's economic paradigm, whilst the two events and related failed policy experiments became critical points that initiated Phase 4 and the formulation of third-order changes.

The EU also had concerns about how China's closed state–market trade and industrial policy and ‘Made in China’ strategy were challenging the liberal market model through unequal competition, (Demertzis, 2019; Annex S1, Interview D). One of the most significant policy experiments related to this concern was the French and German attempt to merge Alstrom and Siemens to increase the companies' capacity to match the Chinese state-owned China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC). However, due to competition legislation, the merger was blocked by Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager (Deutsche Welle, 2019). This again marks Phase 3 in the paradigm evolution with a failed policy experiment. This was interpreted as the liberal industrial policy being unsuitable for addressing the more confrontational world order, this time in the form of a more expansionist China. Thus, both public and private actors in industrial policy go through a continuous social learning process, just without the dramatic events seen in trade policy.

The development confirmed that Causal Chain 1, Rhetoric and Policy Outlier, could be written off, as the observable implication of loss of legitimacy was identified as part of failed liberal policy experiments. Both Phase 2 regarding anomalies and Phase 3 regarding failed first and second-order changes are identified.

The developments in industrial and trade policy reveal a delegitimisation of the existing paradigm, which is crucial for anchoring a subsequent alternative paradigm. Consequently, Causal Chain 1, ‘Rhetoric and Policy Outlier’, can be dismissed, as the observable implication of legitimacy loss is identified as part of failed liberal policy experiments. Thus, Loop A (Figure 1), which leads back to paradigm stability within the evolutionary framework, does not occur.

Causal Chain 1 was further disproved, as Phase 4 could be traced under the Juncker Commission to Macron's speech at the Sorbonne in 2017, which formulated a vision of a new common European strategic culture in response to a more confrontational world order, laying the seeds for Germany and France's later trade and industrial policy manifesto (Ouest France, 2017).

The manifesto was published as a response to the developments and contains the resilience goal of ‘economic sovereignty and independence’ and formulated 14 policy proposals for the Commission (Annex S2). The majority were third-order changes, for example, public financing of strategically important sectors through the state aid exemptions in the IPCEI and strategic activation of EU funds (Annex S2: Proposals 1, 2, 4, 9, 10). In addition, beneficial regulation was proposed within certain sectors such as artificial intelligence and climate technology, which constitute the second leg of a new strategic industrial policy (Proposals 6 and 7). With regard to trade, a new strategic policy was also seen in the form of stronger foreign direct investment screening and new geo-economic tools (Proposals 12 and 13). The manifesto also contained liberal first- and second-order changes such as the completion of the Capital Markets Union (CMU) (Proposals 5 and 14). However, the liberal instruments support the new strategic objective, as it strengthens resilience through, for example, improved access to European capital (BMWK, 2019, p. 3). In general, the manifesto thus drew the first outlines of a new ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm for the EU's industrial and trade policy, which, however, also incorporated elements of the neoliberal paradigm.

At roughly the same time, France and Germany, in collaboration with the Commission, commissioned the think tank European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) to prepare a report with policy recommendations to achieve European sovereignty in a confrontational world order (Delphin, 2021, p. 46; Haroche, 2023, p. 975). The initiation of Phase 4 was thus driven by the macro level and the foreign policy subsystem.

VI Analysis: Part 2 in Figure 2 – Franco-German Momentum (Phases 4 and 5)

This part of the analysis examines policy formulation in Phase 4 and whether momentum for an alternative policy paradigm to be adopted at an institutional level emerged in Phase 5 under the von der Leyen Commission.

Whilst the policy development of an alternative paradigm began under the Juncker Commission, it developed further at the beginning of the von der Leyen Commission, where two related reports were decisive.

When the new Commission took office, a new strategic policy agenda for industrial and trade policy had already been formulated, ready to meet the geopolitical ambitions. In addition to the Franco-German manifesto, the ECFR's report had just been published under the name ‘Strategic Sovereignty: How Europe can regain the capacity to act’. It contained a broad policy agenda with concrete proposals to strengthen the EU in a more geopolitically oriented world order. The initiatives were divided into three main tracks: (1) Economics and Finance, (2) Security and Defence and (3) Politics and Diplomacy, of which the economic leg had been prepared in collaboration with the economic think tank Bruegel (Leonard and Shapiro, 2019, p. 9). With this, the paradigm development was again driven by a foreign policy subsystem with the involvement of economic actors.

The economic proposals were divided into five subcategories, which had direct parallels to the anomalies of the Juncker Commission (Annex S3). Thus, the subcategories US Dollar and Financial Market Dominance and Secondary Sanctions addressed the challenges of the Trump administration, whilst Lack of Investment Transparency and Competition Policy focused on the structural challenges of China's state capitalism. Like the manifesto, the policy agenda was a variation of new strategic third-order changes and neoliberal elements. The strategic proposals included, amongst other things, exceptions in competition legislation with a view to fostering ‘European champions’ within sectors such as digitisation and green transition, for which targeted and increased use of EU funding sources such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) for financing strategic sectors was proposed (Leonard and Shapiro, 2019, p. 29). In trade policy, instruments outside multilateral institutions were also proposed so that economic coercion could be addressed more quickly (Leonard and Shapiro, 2019, p. 45). In addition, there were neoliberal elements such as the CMU (Proposal 1). The prioritisation was again in favour of the new strategic elements due to the overall objective of economic resilience. Thus, the ECFR further developed the Franco-German ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm with neoliberal sub-components.

The economic leg was followed up by the ECFR's second report ‘Defending Europe's Economic Sovereignty: New ways to resist economic coercion’ (Hackenbroich, 2020). The report was developed in collaboration with France and Germany with a task force consisting of, amongst others, the foreign ministries, the Franco-German business community and academia (Hackenbroich, 2020, p. 7).

The work ended in 11 initiatives (Hackenbroich, 2020, p. 8), where the proposal for a common European instrument as a response to economic coercion was most central (Annex S4, proposal 6). Meanwhile, several recommendations, inter alia a compensation fund for trade disputes, were seen as supporting instruments (Annex S4, proposals 1, 3, 9, 10 and 11). The report thus showed how, in collaboration with France and Germany, a third-order policy agenda was being developed for an alternative ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm for the EU's industrial and trade policy consisting of new strategic as well as liberal elements. The process also reflected how economic actors were included in the foreign policy subsystem. However, the driving foreign policy angle was still dominant, and it can be noted that the instruments of ECFR's report were conceived of as a foreign policy regime as opposed to the supranational decision-making procedures regarding industrial and trade policy (Hackenbroich, 2020, p. 9).

At the inauguration of the new Commission, von der Leyen set out a number of priorities for the political programme, with climate, digitisation and geopolitics at the centre (European Commission, 2019a). The geopolitical ambitions were institutionalised in the Commission's policy work through the creation of an external co-ordination unit, where all legislative files with geopolitical potential are discussed weekly at cabinet level (European Commission, 2019b; Haroche, 2023). With this, a macro-political prioritisation was established, where policy subsystems are systematically managed based on geopolitical objectives. In addition, the French Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton had early ambitions for an active resilience-based industrial policy, which inter alia manifests itself in initiatives such as business networks to promote ecosystems within sectors considered strategically important. The opposite pole to the development consisted of the Commissioner of Competition Margrethe Vestager, whose position, however, was considered to have weakened in the second Commission period (Stolton, 2023). With this, there are policy entrepreneurs in the Commission, as well as political pressure for subsystems to incorporate geopolitical objectives into policy.

The macro-political leadership for new strategic policy was also reflected in the European Council, where Emmanuel Macron had been actively developing the concept of strategic autonomy since the Sorbonne speech, inter alia regarding economic resilience, with which a common co-ordinated French pressure arose (Van den Abeele, 2021, p. 20). Although several liberal member states such as the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden expressed scepticism towards Macron's ambitions through the formulation of a joint non-paper (Van den Abeele, 2021, p. 21), contrary to the establishment of the neoliberal paradigm, no new rival liberal project had been formulated that addressed the problems and losses of legitimacy from the Juncker Commission. The absence of liberal policy entrepreneurs meant that there was no significant counterbalancing at a strategic level, whereby Germany also did not play the same balancing role as before Brexit (Annex S1, Interview D).

Whilst the experiences of the Juncker Commission are gradually changing the perceptions of industrial and trade policy amongst certain actors, there were two exogenous events during the von der Leyen Commission that fundamentally changed the perception of the EU's industrial and trade policy on the broad institutional agenda: Covid-19 and Russia's attack on Ukraine.

Covid-19 changed the perception at an institutional level, as it illustrated clearly a lack of European resilience in areas from health through to sudden shortages of chips and critical raw materials (Damen, 2022, p. 3; Annex S1, Interview B). It created consensus that active industrial policy can be justified within these strategic areas (Damen, 2022, p. 3). Since the Commission's industrial policy strategy was being formulated as part of the pandemic's economic problems, resilience targets were therefore also incorporated within certain sectors such as climate and digitalisation (European Commission, 2021a). With this, the strategic third-order changes started to be dealt with at the institutional level, within which Phase 5 of the paradigm evolution begins (European Commission, 2021a, p. 1).

As an emergency measure in addition to NextGenerationEU, which is a new breakthrough but at the time not associated with industrial policy thinking, the Commission chose to publish a revision of the application procedures for the state aid exemptions in the IPCEI (Poitiers and Weil, 2022). Covid-19, therefore, fragmented the legitimacy of the efficiency approach regarding industrial and trade policy and also opened up new financing mechanisms.

Russia's war against Ukraine and the accompanying sanctions put an end to the EU's ‘Wandel durch Handel’ foreign policy, and the EU's global competitiveness suffered serious losses due to energy price increases. The problem applied particularly to Germany and led to a desire for increased state aid for business (BMWK, 2023). The economic implications of Russia's war were addressed through the Versailles Declaration (Council, 2022a), where EU heads of state formulated a common response to Russia's invasion under France's EU presidency.

This brought the problem and policy variables together again, with France attaining ideal conditions for acting as a policy entrepreneur with support from Germany. Specifically, the European Council set the objective of increasing economic resilience (Council, 2022a, p. 3, point c) within certain sectors such as critical raw materials with requests for supportive financial instruments, including state aid exemptions and public financing through, for example, the EIB (Council, 2022a, pp. 7, 9). Trade policy was also addressed, calling, amongst other things, for strengthened handling of economic coercion (Council, 2022a, p. 9). This shows how new strategic policy ideas from the Franco-German manifesto and ECFR were adopted through an institutionalised declaration of intent at the EU level on the establishment of a new paradigm for industrial and trade policy.

In order to implement the declaration, the Commission was requested to develop a REPowerEU plan (Council, 2022a, p. 6), to be published 1 month later, and at the same time, it had to present a concrete policy agenda (EUR-lex, 2022, p. 1). Although the plan focused on energy, it had broad implications for industrial policy, as a large number of underlying new strategic instruments were presented. For example, the temporary Covid instruments, NextGenerationEU and state aid exemptions, as well as the use of previous sources such as InvestEU and the EIB to secure the resilience objectives, were opened up (EUR-lex, 2022, pp. 17–19). The Commission thus presented proposals for increased public involvement in the market at the same time as it adopted a ‘picking the winner’ approach, where sectors such as hydrogen, solar cells and critical raw materials were identified as strategically important (EUR-lex, 2022, p. 10).

All in all, the second part of the analysis shows that a linking of policy, politics and the problem variables in the form of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine enabled the adoption of a new strategic policy paradigm at an institutional agenda. Causal Chain 2, Early Paradigm Stage, can be written off, as an alternative paradigm was formulated by policy entrepreneurs and institutionally addressed by an initial coalition, constituting the two observable implications. Since the development was driven by the EU's macro level and the foreign policy subsystem, the question is whether it could be institutionalised at the subsystem level in the policy process.

VII Analysis: Part 3 in Figure 2 – Presentation and Negotiation of Proposals (Phases 6 and 7)

Analysis of Part 3 in Figure 2 examines whether the adopted agenda from Phase 5 is institutionalised with a focus on the formulation and negotiation of the CRMA and the ACI. If Phases 6 and 7 are identified, it can be concluded that a ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm has been established as far as these two cases are concerned.

The Institutionalisation of Industrial Policy – CRMA

Phase 6 of the paradigm evolution began shortly after the launch of REPowerEU, with von der Leyen presenting the start of CRMA. Subsequently, Breton's DG GROW presented an initial analysis on CRMA (European Commission, 2022); at the same time, France and Germany advanced a joint position on CRMA (BMWK, 2022). With this, active policy entrepreneurship continued in Phase 6. In the initial analysis, the objective was resilience-based, whilst the instruments represented both neoliberal and new strategic ‘Homeland Economics’ measures. However, the new strategic ones primarily consisted of regulatory instruments, whilst the financial ones were not included.

Parallel to the formulation of the CRMA, a European fear arose that the United States' adoption of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) would draw green investments out of the EU (Scheinert, 2023). It culminated in von der Leyen launching a green industrial legislative package during a speech in Davos (European Commission, 2023a), in which CRMA was incorporated together with the quickly drafted twin proposal Net-Zero Industry Act (European Commission, 2023a). In addition, von der Leyen launched new associated strategic financing instruments in the form of state aid, EU funding and even a so-called Sovereignty Fund (European Commission, 2023a). The IRA thus constituted another exogenous shock, which policy entrepreneurs used to promote the new strategic ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm.

After the Davos speech, the industrial package was presented, where the core of CRMA was a differentiation of the strategic importance of raw materials, as critical ones for defence, digitisation and green transition were categorised as Strategic Raw Materials, which are covered by new strategic regulatory and financial instruments (European Commission, 2023b, p. 15). The latter consist of, amongst other things, state aid exemptions as well as investments from the EIB and EU programmes such as NextGenerationEU. With this, the proposal's strategic elements were significantly strengthened throughout the formulation phase. However, the Sovereignty Fund was never to be incorporated, which is why the proposal's new strategic elements did not go further than the idea formulation from Phase 4 in the form of regulatory benefits and targeted use of existing funding sources.

The policy formulation aroused great interest from private actors, which was reflected in more than 300 consultation responses (European Commission, 2023b). They basically accepted the premise that certain strategic sectors and materials would be selected for advantageous treatment (Ragonnaud, 2023, p. 9). Amongst the organisations interviewed, there was also an understanding of an active industrial policy in areas such as critical raw materials, although problems were also pointed out because the proposal had the character of being a fait accompli (Annex S1, Interview C). The new strategic elements were stated to be overriding public interest, and actors outside the circle of support found this difficult to oppose due to a political prioritisation from the EU's high political level (Annex S1, Interview E).

The limited business resistance regarding the proposed policy can be explained by liberal business actors having a positive incentive to support the active industrial policy, as there is an opportunity to obtain an advantageous regulatory and financial framework in their own areas. The consultation responses also focused on the fact that business actors want their own areas and products categorised as strategically important (Ragonnaud, 2023, p. 9). In this way, a collective action problem arises amongst business actors, where there is a risk associated with opposing the new strategic policy elements. The primary opposition came from NGOs concerned about the social and environmental consequences of giving regulatory special treatment to the mining of strategic materials (Ragonnaud, 2023, p. 9; Annex S1, Interview B). A post-liberal coalition consisting of neo-mercantilist and socially oriented actors could not therefore be identified (Seidl and Schmitz, 2023). On the contrary, a typical industrial political business–NGO dividing line was seen. Lack of business resistance created an opportunity for a new strategic policy to be translated into concrete policy.

The processing of the proposal was a matter of priority in the European Parliament, where the rapporteur was the German MEP and vice-president Nicola Beer (Renew) in the Industry Committee (ITRE) (Beer, 2023; European Parliament, n.d.-a). In the Council too, CRMA was also considered a matter of priority, and there was consensus on the overall objectives of the proposal (Annex S1, Interview F). This meant that the later trilogue negotiations were primarily characterised by discussions about technical matters such as the extent of administrative burdens for authorities (Annex S1, Interview G). Thus, the negotiations dealt with first- and second-order changes, whilst the third-order variations in CRMA were clarified before the broad circle of actors and the formal institutionalisation processes were launched. This applied to the Sovereignty Fund, which was never officially discussed.

Since the end of the negotiations, the strategic objectives and instruments in CRMA have been maintained with the exception of minor changes. With this, Causal Chain 3, ‘Homeland Economics’ Component, can be rejected. The new strategic policy has become institutionalised as a core component of the CRMA, as there is limited resistance from both institutional and private actors in the industrial policy subsystem. Thus, the evolution process moves to Phase 7 Institutionalisation of a new paradigm, and Causal Chain 4, ‘Homeland Economics’ Paradigm, is identified. There is thus a new paradigm in the EU's industrial policy, where resilience objectives and favourable regulation and financing will characterise strategic areas.

Institutionalisation of Trade Policy – ACI

In February 2021, DG Trade presented an initial impact assessment of the ACI, which stated that the proposal was formulated on the basis of ECFR's report on economic coercion and a joint institutional declaration that obliged the Commission to develop a new instrument (European Commission, 2021b). The declaration was the result of the European Parliament's intention to incorporate a similar instrument into another trade policy act, which was, however, considered to be too far-reaching (European Parliament, n.d.-b). The proposal thus comprised both a foreign and trade policy work track.

The chairman of the European Parliament's committee for International Trade and later rapporteur on the proposal, MEP Bernd Lange, put early pressure on a high level of ambition in the proposal and rapid presentation with support across the European Parliament's groups (European Parliament, n.d.-c), with which the European Parliament's trade committee has a reinforcing effect on the new strategic policy. DG Trade was given responsibility for the design of the ACI, whilst the intended legal basis lay in the EU's common commercial policy (European Commission, 2021b, p. 2); this is why it was formulated as a trade policy and not a foreign policy instrument, which is close to the European Parliament's understanding.

Shortly before the proposal was made, Taiwan opened a representative office in Lithuania, which resulted in China launching sanctions against Lithuania that had broad implications for European companies, amongst them French and German entities. This was, however, only the last straw in the Chinese policy pressure towards the EU (Schild and Schmidt, 2023). The Lithuanian case was submitted to the WTO without major results, which again emphasised the need for the ACI. At the same time, ECFR published a new report with more detailed design recommendations for the instrument (Hackenbroich and Zerka, 2021). This continued the early policy entrepreneurship in the negotiation of the third-order changes. The macro level and policy entrepreneurs therefore remained relevant as high-level attention continued throughout the evolutionary process.

The actual proposal for ACI from DG Trade was to be formally presented in December 2021. It was based on a two-stage model, which meant that the Commission could initiate countermeasures against third countries through delegated and implementing acts, thereby giving them far-reaching competences (European Commission, 2021c, p. 8). At the same time, the legal basis of the proposal remained under the Common Commercial Policy as announced in the initial impact assessment (European Commission, 2021c, p. 2). It should be noted in this regard that the Common Foreign and Security Policy is in the Treaty on the EU, where articles 3 and 21 stipulate that the EU's external relations shall promote multilateralism and multilateral solutions to problems; however, trade policy is in the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU. The ACI proposes the adoption of action outside multilateral institutions and rules based on international law. Therefore, a 2015 Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruling required the Commission to have a legal basis on which to invoke this justification, a function now served by the ACI (Weiss, 2023).

Furthermore, it was a point of discussion in the ECFR's task force in Phase 4 that it was exclusively the Commission that should assess whether a third country was exercising economic coercion, which is also of substantial importance, as a supranational instrument can be implemented more quickly. The discussions from Phase 4 about a resilience office and fund were also addressed in the formulation phase but were removed from the proposal due to budget constraints (European Commission, 2021c, p. 5).

The consultation responses reflected the positions of member states towards a new strategic paradigm amongst private actors. Thus, the French interest organisation Association française des entreprises privées (AFEP), which represents large French companies such as Airbus and Total, wanted an ACI with a large deterrent effect and compensation through a resilience fund as proposed in ECFR's report (AFEP, 2021). The Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, on the other hand, criticised the new strategic trade approach on principle and distanced itself from the idea of deterrence (Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, 2021). However, it can be noted that only 22 consultation responses had been submitted to the ACI, as opposed to the 300 in the CRMA consultation (European Commission, 2021b).

The low interest was illustrated by the fact that liberal-oriented business actors have principled reservations towards the ACI, but limited real interest or fear of the instrument (Annex S1, Interview C + E). Their focus was again on free trade agreements, where it was even pointed out that a new strategic trade policy paradigm could have a positive impact if an increased diversification focus leads to momentum for liberal trade agreements (Annex S1, Interview E). The ACI only drew attention from a few large multinational companies. Although there were therefore disagreements in the area, the real focus was on specific trade agreements that have direct implications for member companies. However, it should also be noted in this regard that the ACI is not intended to address the underlying political reason for the application of economic coercion; it is merely aimed at the economic (commercial) ramifications of economic coercion.

In the Council, despite its geopolitical purpose, the file was assigned to the Competitiveness Council (COMPET) group, which is represented by the ministers for trade, economy and industry. This meant that on the Council's side, there was a replacement of civil servants, as the proposal was negotiated by the ministries of economy and business. However, the foreign policy angle had already been established, which is why there was criticism of the proposal's legal basis in commercial policy. After the Council's investigations, it was concluded that the sub-elements in the proposal actually constituted foreign policy, which is why the delegated and implementing acts were problematised, since the member states could only vote for or against with a qualified majority (Gijs, 2022). In the Council's final compromise, the text was also adjusted significantly in relation to the assessment of countermeasures (first step) and the implementation of the countermeasures (second step) (Council, 2022b), which was desired by Germany and several trade liberal member states (Gijs, 2022).

The European Parliament was more positive towards the Commission's proposal, where, with the exception of the EU-sceptic ECR group, there was a desire for a strong supranational instrument (Annex S1, Interview A, Giys and Moens, 2023). Thus, the negotiation conflict rested on issues of competence and less on whether the instrument must go through multilateral organisations. Discussions about the deterrence element from the ECFR thus continued in the negotiations but started from the question of competence.

The negotiations resulted in the member states being countered on the inclusion of the Commission's preparation of countermeasures. But this happened with a qualified majority and not with unanimity. The liberal element of multilateral co-operation was strengthened in the wording, as the Commission should try to use WTO consultations, but without the instrument actually being dependent on multilateral rules or agreements (EUR-lex, 2023). The result shows that it was successful in institutionalising a strategic trade instrument, whereby Phase 7 Institutionalisation of a New Policy Paradigm and Causal Chain 4, ‘Homeland Economics’ Paradigm, are identified in trade policy in relation to instruments outside rule-based regimes. Contrary to industrial policy, however, consensus in the trade policy subsystem is less deeply rooted. The neoliberal subcomponent of ‘Homeland Economics’ could thus be expected to be stronger in trade policy.

Conclusion

As a result of the analyses of this article, we claim that the application of Oliver and Pemberton's paradigm evolution theory has demonstrated its value. It has nuanced the analysis of CRMA and ACI as examples of a paradigmatic development of the EU's industry and trade policy from a neoliberal paradigm to a ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm. As mentioned, we have shown that this granular development is less either/or than often thought.

The neoliberal paradigm already fragmented during the Juncker Commission. Brexit shifted the coalition composition in the EU as it lost its neoliberal leader, which opened the way for traditional French positions. In addition, the first Trump administration's undermining of the liberal world order as well as China's booming exports put the neoliberal paradigm under pressure. It lost legitimacy amongst EU decision-makers, not least at the foreign policy subsystem level.

At the beginning of the von der Leyen Commission, an alternative paradigm developed further with inputs from ECFR reports. Gradually, a Franco-German ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm was beginning to take shape. It represented a more realist and geopolitically oriented paradigm, but with neoliberal subcomponents. The institutionalisation of the new paradigm accelerated further due to Covid-19 and Russia's attack on Ukraine in 2022. With this, third-order changes began to be dealt with and a more fully fledged Homeland Economics paradigm materialised.

This article examines CRMA and ACI. We have identified a new ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm in the two analysed policy fields where resilience objectives and favourable instruments will characterise strategic areas. We conclude that CRMA represents a new policy paradigm in the EU's industrial policy where resilience objective and favourable regulation and financing will characterise certain strategic areas. Compared to industrial, consensus in the trade policy subsystem is less deeply rooted. Hence, the neoliberal subcomponent is stronger as far as ACI is concerned. All in all, based on the paradigm evolution theory, we have demonstrated how the EU's industrial and trade policy has fundamentally changed its character, in a process taking several years, against the backdrop of active policy entrepreneurs and a new member state coalition structure after Brexit.

This article contains two case studies. A next step will therefore be to investigate how widespread the new paradigm is by looking at other legislative proposals with a less pronounced geopolitical angle. An analysis of less clear cases can shed more light on the content and strength of the ‘Homeland Economics’ paradigm.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to August Kronæsgaard Søby Nissen for research assistance. In addition, Terry Mayer, as a language editor, has also made a great effort to make the article publishable. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their thorough review of the first draft of the article. In addition, the editor of JCMS has contributed valuable comments to our manuscript.