Defining and Operationalising Defiant Non-Compliance in the EU: The Rule of Law Case

Abstract

Existing literature often attributes non-compliance to either a lack of resources or implementation costs. However, the rule of law crises in Hungary and Poland present a different picture: a deliberate strategy aimed at not complying with EU enforcement actions. This article differentiates this model from previous ones and terms it ‘defiant non-compliance’, which is characterised by four types of domestic actions (ignoring the Commission's recommendations and warnings; not complying with Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) rulings; questioning the role of the CJEU as the sole final interpreter of EU law; and impeding national courts' right to raise preliminary questions). A defiant rhetoric questioning the authority and legitimacy of the enforcing authorities accompanies these actions. The article distils defiant non-compliance by systematising empirical evidence on these governments' reactions to EU enforcement. This model of non-compliance severely threatens the foundations of the EU, as it erodes the notion of a community of law-abiding member states' governments.

Introduction

The rule of law (RoL) crisis in Poland and Hungary has proven to be a profound existential threat to the EU. Since 2010 and 2015, respectively, the Fidesz-Hungarian Civic Alliance (Fidesz) and Polish Law and Justice (PiS) governments (the latter until the end of 2023) have engaged in a concerted effort to backslide on their liberal democratic regimes, inevitably leading to a clash with EU norms and values. EU enforcement actions have had little effect on compelling the member states' governments to return to compliance. Worse, national authorities in these backsliding states have openly challenged the EU's authority, including validly enacted laws and the obligation to comply. Whilst non-compliance has not been uncommon throughout EU's history (European Commission, 1984–2022), the specific characteristics of non-compliance in RoL-related issues represent an existential and distinctive challenge to the EU project (Coman, 2022, p. 271).

This article thus introduces and defines the notion of ‘defiant non-compliance’ as a distinctive type of non-compliance. Whilst other types of non-compliance do not aim at dissolving the very foundations of the EU's functioning (i.e., national governments' voluntary compliance with EU law), defiant non-compliance regarding the RoL directly erodes the underpinning of the EU as a community of law. Defiant non-compliance is a distinct modality that not only involves a deliberate and overt strategy of non-compliance with EU rules but also represents an explicit challenge to, and questioning of, the authority responsible for creating and enforcing those rules. It goes beyond an opportunistic denunciation of specific policies and measures and is in direct confrontation with the EU's membership model. The aim here is therefore to shed light on what defiant non-compliance is. Providing such characterisation is the primary contribution of this article.

The second contribution involves operationalising the elements of defiant non-compliance and unravelling how it is manifested. We argue that this behaviour encompasses defiant actions directed against enforcement measures carried out by centralised [i.e., European Commission (Commission) and Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU)] and decentralised enforcing institutions (i.e., national courts), combined with a belligerent rhetoric against the source of authority. This article examines the patterns of defiant non-compliance that can be found in the two empirical cases where the phenomenon has been observed (the Polish and Hungarian authorities), with the aim of identifying differences and similarities. We assess qualitatively the actions that typify defiant non-compliance, together with descriptive statistics to examine their frequency, categories and targeted institutions. By systematising the analysis of the concept in this way, we establish its distinct nature compared to other types of non-compliance.

The article is structured as follows. The first section will review theories on the voluntary compliance model on which supranationalism relies, the explanations of why non-compliance occurs and the non-compliance debates related to the RoL crisis. This review will provide a theoretical explanation for the occurrence of defiant non-compliance. Furthermore, it will anchor and introduce the definition of defiant non-compliance as qualitatively different to previous instances of non-compliance. It also serves to identify four specific actions that typify non-compliance in RoL-related cases. The next section will operationalise defiant non-compliance, present the data collected for examining patterns of defiant non-compliance in Poland and Hungary and provide some methodological considerations for its analysis. This will be followed by a discussion of the findings, whilst the conclusion will summarise the theoretical implications of this research.

I Theoretical Debates on Compliance and Non-Compliance: What Is Defiant Non-Compliance?

The EU model of integration is based on voluntary compliance with EU law. The key to the whole system is the implicit and explicit acceptance of the notion of ‘community of law’, a term that was introduced in the 1960s by the first President of the Commission, Walter Hallstein, and later echoed by the CJEU (Les Verts, C-294/83). This involves the existence of law-abiding states committed to complying with EU rules, that is, a self-imposed duty to implement and observe them. Thus, even when facing norms that they consider not to be beneficial for them, member states' governments cannot selectively derogate EU legal provisions or choose not to comply with them. And this commitment often persists despite weak or non-existent enforcement mechanisms that might otherwise coerce it (Börzel, 2021; Thomson et al., 2007). Thus, the premise of voluntary compliance also has implications for the way the Union addresses non-compliance.

Many authors agree that there is a compliance problem in the European Union (Cremona, 2012; Falkner, 2018; Falkner et al., 2004; Toshkov et al., 2010). Börzel (2021, pp. 3 and 4), however, has disputed this view, asserting that there is no evidence of a non-compliance problem and arguing that non-compliance has, in fact, decreased, even though steps towards further integration have been taken and the EU has doubled in size. Nonetheless, Kelemen and Pavone (2023) noted the Commission's preference for taking a forbearing approach (Holland, 2016), rather than working to improve national governments' compliance, goes a long way to explaining the decrease in the use of law enforcement instruments.

Non-compliance refers to state behaviour that does not conform to the obligations prescribed by a legal order (i.e., domestic, international or EU) to which a given state has committed itself (Chayes et al., 1998, p. 39; Young, 1979, p. 104; cf. Börzel, 2021, p. 4; Raustiala and Slaughter, 2002). Whilst non-compliance threatens the basic agreement upon which legal orders are constructed, it is common in most systems. Specifically, even those who recognise authority and generally support the existence of specific behavioural guidelines in international organisations often find it beneficial to ignore those rules in practice (Young, 1979). Why does non-compliance happen? Most of the literature has discussed the domestic origins of non-compliance from two alternative perspectives: either capacity or power (costs). This debate is important not only for compliance but also as regards the strategies for inducing compliance, labelled as either ‘management’ or ‘enforcement’, respectively (Tallberg, 2002).

On the one hand, part of the literature attributes non-compliance to a lack of domestic capacity and rule ambiguity (Chayes and Chayes, 1995; Tallberg, 2002). Management theorists embrace a problem-solving approach based on capacity building, rule interpretation and transparency. They assume that non-compliance results from misunderstandings of legality or capacity limitations. In this line, Arregui (2016) showed that the variation in legislative implementation can be explained by differing levels of administrative effectiveness (higher levels improve compliance), amongst other factors. Falkner et al. (2004) pointed to administrative shortcomings as crucial factors explaining transposition problems, whereas Treib (2014) conducted a historical review of compliance theories and identified the number of veto players at domestic level as a relevant factor in explaining compliance capacity. Member states' perceived capacity for complying also shapes enforcement preferences (Closa, 2021; Franchino and Mariotto, 2021).

On the other hand, enforcement theorists argue that costs and incentives explain actors' compliance and non-compliance: powerful actors simply will not comply because they can afford to be sanctioned (Tallberg, 2002). Enforcement theorists characteristically stress a coercive strategy entailing monitoring and sanctions, as they view non-compliance as a cost–benefit calculation where higher sanctions are expected to deter violations. Thomson et al. (2007) highlighted incentives to deviate and discretion in implementing legislation as factors explaining the success of EU law enactment, downplaying differences amongst states. The interviews conducted by Dörrenbächer (2017) revealed instrumental implementation motivations such as avoiding national punishment, whilst explicit national guidelines can discourage EU law use. Other interview-based research has also shown how national administrative authorities prioritise domestic requirements over EU legislation (Mastenbroek, 2017). Falkner et al. (2004) also noted that the aim of governments to protect their national regulations vis-à-vis EU rules accounts for non-compliance, although they made a distinction between governments that were strongly opposed during the decision-making stage and those that were not, the latter being the most numerous. These explanations were consistent with Börzel's (1999) argument, which focused on structural overtones: that goodness of fit (i.e., regulatory isomorphism between the supranational level and the domestic level) determines both non-implementation and non-compliance.

However, a mechanical application of both capacity limitations and incentives for deviation may overlook the role played by the ideological and political preferences of domestic actors. In fact, alignment with these domestic preferences is a predictor of the ease with which new EU legislation will be implemented (Mastenbroek and van Keulen, 2006). Hence, a focus on actors has achieved a greater prominence in explaining compliance, as the resources they may activate in the presence of a misfit explain compliance and non-compliance. Focusing on actors sheds light on their enforcement preferences (Closa, 2021). In a last refinement, Börzel (2021) added politicisation to the classical duality of capacity and power. Politicisation alludes to national political conflicts derived from compliance with EU law, ‘which crucially affects the ability of states to shape and take compliance costs’ (Börzel, 2021, p. 6).

Neither the conventional explanations centred on capacity nor those related to costs seem to offer a nuanced understanding of RoL-related non-compliance cases. Instead, what is at play is a deliberate strategy of non-compliance grounded in ideological positions (Bugaric and Kuhelj, 2018; Coman and Leconte, 2019; Pirro and Stanley, 2021). ‘Defiant non-compliance’ is fundamentally distinctive because of how it manifests: it surpasses mere non-compliance, as it involves directly challenging the enforcement authorities. Contrary to Börzel's (2021, p. 2) assertion that the Hungarian and Polish governments' violation of EU rules was comparable to that of the Greek and Italian governments during the fiscal crisis, since non-compliance affects core norms and rules, we contend that the behaviour of the Budapest and Warsaw governments represents a specific form of non-compliance. The differential factor derives from the tactics and justification used for non-compliance with enforcement actions. It also goes one step further from ‘symbolic and creative compliance’ (Bátory, 2016) in which governments engage to create the appearance law-abiding behaviour without giving up their original objectives. In defiant non-compliance, governments not only fail to substantially comply, but they also challenge the very foundation of the authority that enacted the rules as much as the rules themselves.

Additionally, defiant non-compliance goes beyond the fourfold typology of non-compliance traditionally established by the Commission (1984–2022; see also Börzel, 2021, pp. 14–15) within the EU framework. The first three types of non-compliance relate to directives and cover issues such as failing to communicate the implementation of measures, incorrect transposition and active or passive infringements. The fourth category is broader, as it encompasses non-implementation or incorrect enforcement of directly applicable Treaty provisions, regulations and decisions. RoL non-compliance falls under this category, specifically related to Art. 2, as it involves enacting, or not repealing, national measures that contradict EU law. Furthermore, the inclusion of a defiant rhetoric challenging the authority of the EU intensifies this phenomenon.

Therefore, defiant non-compliance refers to intentional and persistent failure to comply with EU law, accompanied by assertions that contest its legitimacy and validity, as well as the authority of the institutions responsible for its enforcement. Broadly, this form of non-compliance targets enforcing mechanisms (i.e., non-complying with enforcement actions) and finds its expression through a forceful, defiant discourse that questions the legitimacy of EU institutions to enforce the law. Further, it questions the authority of the EU itself to prevent non-compliance. Defiant non-compliance targets centralised and decentralised institutions of enforcement, which comprises both political and judicial authorities. Table 1 summarises the indicators of defiant non-compliance.

| Indicators of defiant non-compliance | Targeting centralised enforcement | Targeting political authority | + Defiant rhetoric |

| Ignoring and overlooking the Commission's recommendations | |||

| Targeting judicial authority | |||

| Dismissing CJEU rulings | |||

| Mobilising national courts against EU law/rulings | |||

| Targeting decentralised enforcement | Impeding the prerogative of national lower courts to request preliminary rulings |

The first component refers to the explicit negative reaction to the Commission's implementation request for complying with EU rules. Centralised mechanisms, often relying on soft enforcement tools, have proven ineffective in countering this strategy of resistance to enforcement measures (Kelemen, 2022; Kochenov, 2019; Pech and Scheppele, 2017; Uitz, 2019). Whilst some authors have affirmed that material sanctions are not particularly effective in cases of democratic backsliding, and rather advocate for improving the transformative power of monitoring and social pressure (Lacatus and Sedelmeier, 2020; Sedelmeier, 2017), most scholars agree on their weaknesses in bringing about compliance in the cases of Poland and Hungary (Priebus, 2022; Uitz, 2019). Whereas the Commission generally holds that dialogue and engagement with breaching authorities may be sufficient to obtain compliance (Closa, 2018), it has been increasingly assertive in recent years (Blauberger and Sedelmeier, 2024; Hernández and Closa, 2023; Kelemen, 2024). This has been made apparent in infringement procedures, where Commission cases rarely reach the Court stage due to a preference for making out-of-court settlements (Closa, 2018; Kelemen and Pavone, 2023). Thus, we posit that the initial manifestation of defiant non-compliance is found in the disregard and rejection of the Commission's recommendations for improving compliance (in this case, recommendations aimed at reversing democratic backsliding).

The second component of defiant non-compliance is two-faceted: Backsliding rulers have deactivated both centralised and decentralised systems of judicial supervision and scrutiny, that is, CJEU and national courts. Centrally, EU institutions have favoured infringement actions as their preferred enforcement mechanism, in which the Commission and the CJEU are the main actors. As a reaction, member states' authorities have developed multiple strategies to limit the practical effect of controversial CJEU case law (Hofmann, 2018). Non-compliance with CJEU rulings repeats the broader pattern of non-compliance with EU rules and regulations in general: national authorities do not enforce rulings because they aim to protect important (domestic) interests and avoid costly enforcement measures (rather than attributing this to problems of administrative capacity or interpretation) (Falkner, 2018). In some instances, governments have resorted to ‘creative compliance’ (Bátory, 2016). As for the RoL case, in order to prevent this façade of change, Scheppele et al. (2021) advocated for introducing ‘systemic infringement procedures’, that is, the requirement to fix systemic threats to EU principles rather than merely technical violations of fundamental values. Whilst dissatisfaction punctuates the evaluation of Commission enforcement activity via infringement actions, the performance of the CJEU as an enforcer has adapted to what could have been expected beforehand (Pech and Kochenov, 2021). Thus, the CJEU can deliver instruments that are capable of inducing compliance when suitable grounds exist. Precisely because of this, the CJEU itself has become the target of the defiant rhetoric of non-compliant governments, and this constitutes the second indicator of defiant non-compliance.

The decentralised erosion of control mechanisms does not appear, prima facie, to be an exclusive characteristic of defiant non-compliance. Thus, a number of constitutional courts in different member states have issued judgments that questioned the primacy of EU law, declaring the ‘illegality’ of EU legal provisions and of some CJEU rulings. For instance, the controversial ruling of the German Constitutional Court on the legality of the European Central Bank's bond purchase programmes questioned the primacy of EU law, although the German government later formally stated that it recognised the supremacy of EU law and the binding force of the CJEU's decisions (von der Burchard, 2021). A differential fact in defiant non-compliance is the political capture of domestic constitutional (and other) courts, as found in the Polish and Hungarian cases (Bárd and Pech, 2019; Sadurski, 2019). Political capture of the courts encompasses a variety of practices that fundamentally undermine the independence of the judiciary. This includes legislative changes aimed at increasing the executive's authority over the judicial branch, as well as interference in the decision-making processes of the judges. Here, governments act as plaintiffs, actively seeking to pit national courts against the CJEU, creating a distinctive scenario. Thus, non-compliance involves the refusal to adhere to CJEU rulings by employing national constitutional courts to reject the primacy of EU law or, in other words, to quest constitutional supremacy (Castillo-Ortiz, 2023). Consequently, the third noteworthy characteristic of defiant non-compliance is that national courts systematically become the ultimate interpreters of EU law, questioning the traditional role of the CJEU in this regard.

Finally, preliminary rulings (Art. 267 Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU)) are the bulk of the decentralised EU enforcement system. The actors that have adopted an attitude of defiant non-compliance have sought to remove or diminish national judges' ability to request preliminary rulings. Their efforts have included both legal actions and legislative measures (i.e., court cases and/or pieces of legislation to that effect). Research has consistently established that judges play an entrepreneurial role in mobilising EU law for policy change (Mayoral and Torres Pérez, 2018); judges have also collectively opposed governmental action and defended judicial independence, specifically regarding the RoL, by resorting to tools such as preliminary rulings (Matthes, 2022; Puleo and Coman, 2023). Research has found that backsliding governments have used two instruments related to this fourth modality: disciplinary proceedings against judges asking for preliminary rulings and, more broadly, legislation prohibiting or limiting their use (Bárd, 2021; Pech, 2021). Consequently, the fourth type of action within defiant non-compliance refers to mechanisms and procedures seeking to impede the issuance of preliminary rulings by lower courts.

II Research Design: Operationalising Defiant Non-Compliance

How to Operationalise Defiant Non-Compliance

Table 2 summarises four key actions that serve as indicators for operationalising the concept of defiant non-compliance presented in this article. Taken together, the combination of the four actions of national governments' response to EU enforcement mechanisms makes this model into an explicit strategy for defying compliance.

| Type of defiant non-compliance | Operationalisation | |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring and overlooking the Commission's recommendations | Frequency of instances where EU recommendations or warnings resulting from enforcement instruments (infringement procedures, RoL Framework and RoL Report on Conditionality Regulation) are ignored. | + Frequency of defiant claims/statements rejecting the authority of the enforcing institution |

| Dismissing CJEU rulings | Frequency of instances of non-compliance with infringement rulings (i.e., the infringement procedure is still ongoing despite a decision having been taken and, in some cases, even after a procedure under Art. 260 TFEU has been initiated) or compliance that might not have prevented the initial violation (‘creative compliance’). | |

| Mobilising national courts against EU law/rulings | Frequency of instances of explicit requests by governments made to their constitutional courts to assess the validity of EU legislation, along with court rulings declaring the ‘illegality’ of EU norms and CJEU rulings. | |

| Impeding the prerogative of national lower courts to request preliminary rulings | Frequency of instances of disciplinary proceedings brought against judges requesting preliminary rulings and legislation prohibiting or limiting their use. | |

As mentioned above, the literature has argued that non-compliance is not uncommon. What makes defiant non-compliance qualitatively different is the combination of actions (i.e., non-compliance itself) and the rhetorical justification of such behaviour: national governments develop an aggressive rhetoric against compliance in which they question the EU authorities and law enforcement power. Thus, in order for these actions to be considered to be indicators of defiant non-compliance, they need to be accompanied by national governments' ‘defiant claims’ backing them. Defiant claims are defined here as those claims (or statements) made by government officials declaring their unwillingness to implement, their preparedness to disobey or their rejection of the validity and legitimacy of (certain) EU rules and authority. Unlike the disagreement on the content of the challenged measure, defiant claims refer to the institutional framework for the production of such measures (i.e., enforcement measures).

Cases of Defiant Non-Compliance

The behaviour of the Hungarian and Polish authorities in terms of the RoL during the selected period is a unique modality of non-compliance, defiant non-compliance, which requires intentional and persistent instances of failure to comply with EU law. As other member states' behaviour may provide instances of ‘standard’ non-compliance, comparing them might be useful for explaining any existing differences. However, this article focuses on substantiating this specific modality.

A qualitative overview of the actions characterising defiant non-compliance, combined with descriptive statistics, which cover the frequency of defiant non-compliance claims, the categories of defiant non-compliance behaviour and the types of institutions targeted, serves as the basis for our empirical analysis. We produced and examined a series of graphics and conducted Fisher's exact tests (using PositCloud software) to establish whether statistically significant differences existed between the types of defiant actions displayed by the two governments. For the sake of clarity and parsimony, we have not included all of the databases and tests produced in the main text, but they are open for consultation in Appendix S2.

Data and Sources

The analysis focused on instances of non-compliance exhibited by backsliding governments which spanned the timeframe from 2013 to 2022. The Hungarian Fidesz party, which ruled from 1998 to 2002, did not show a RoL backsliding attitude during this period, and therefore, this time span was excluded from our analysis. Fidesz returned to power in 2010 and remains in office at the time of writing. However, no evidence has been found of defiant non-compliance before 2013, and therefore, this year was taken as our starting point. The approach adopted involved empirically assessing whether defiant non-compliance could be effectively operationalised based on the theoretically expected indicators and whether these behaviour patterns could be identified amongst governments.

The dataset of defiant claims, open for consultation in Appendix S1 (which also provides additional details on the methodology), consists of statements by Hungarian and Polish governments' officials in response to EU institutions' actions seeking to enforce compliance in RoL-related cases. Observations of defiant claims, as identified in our dataset, primarily corresponded to a specific event or action related to EU enforcement procedures (these are specified in the column labelled ‘Specific event challenged’). However, the same event may have triggered several reactions. In other words, there was not one defiant claim per event, but several defiant claims may have been identified for the same EU action. Such statements included cases such as the Polish government's challenge of the Commission's infringement procedure concerning the establishment of a Disciplinary Chamber in the Polish Supreme Court (observations 49, 70, 71, 72 and 73, Appendix S1) and the Hungarian authorities' reaction to the Commission's launch of the Conditionality Regulation (observations 108, 119 and 120), amongst other instances. Only a few observations reflected spontaneous statements by these national authorities regarding the Commission's competences in general terms for RoL monitoring and enforcement in domestic contexts (observations 18, 37, 82, 87, 99 and 107). In other words, they did not question a specific event, but rather RoL enforcement in general terms. The dataset of defiant statements consisted of 121 observations collected from official sources, academic sources, social media and international media specialised in European politics.

We categorised the evidence into four distinct groups that were aligned with the indicators provided in the previous sections. Empirical evidence was retrieved for Category 1 (‘Ignoring and overlooking the Commission's recommendations’) from the Commission's Database on Infringement Procedures in relation to the Commission's reasoned opinions and letters of formal notice (European Commission, 2023); as well as from Hernández and Closa (2023). For Category 2 (‘Dismissing CJEU rulings’), we also relied on the Commission's infringement dataset, supplemented by Pech and Kochenov (2021) for in-depth case analysis. Category 3 (‘Mobilising national courts against EU law/rulings’) was substantiated by identifying national Constitutional Court cases and legislative decisions seeking to cancel CJEU's primacy, in addition to references from Jaraczewski (2021) and Halmai (2022). Finally, Category 4 (‘Impeding the prerogative of national lower courts to request preliminary rulings’) was constructed by referencing domestic cases and legislative measures. Pech and Kochenov (2021) and Pech (2022) provided insight into various instances illustrating our argument (although we do not intend to provide a detailed assessment of all court cases, which exceeds the purpose and scope of this article). Whilst some of the observations could fit into several of these types, we will only indicate the most obvious and paradigmatic typology in each case. Besides the substantive content, basic coding includes the date, the actor defying EU authority, the institution targeted and the category of non-compliance triggering the statement.

The dataset exclusively encompasses RoL-related claims and covers issues linked to the independence of institutions, in particular, the judiciary; the constitutional system; elections; and fundamental rights and freedoms, including those of minority groups such as women and migrants' rights, as well as freedom of the press and academia. These issues were the main concerns raised by the EU regarding the RoL in Poland and Hungary (see Art. 7.1 activation proposals). Although the Hungarian and Polish governments have expressed additional critical viewpoints (for instance, references to alternative visions of the EU such as a ‘Europe of nations’ or dissenting opinions on proposals that are still under negotiation and not yet in force), these have not been included. Likewise, the dataset does not account for the countries' threats to veto these proposals in the Council if they come up for a vote. These critical statements and the associated veto threats are considered ordinary and lawful disagreements in the EU norm-making process, and therefore, they do not represent a defiant attitude towards EU enforcement powers as such.

One limitation of the selection of claims refers to its intrinsically oriented approach: our selection comprises only those cases expressing challenging attitudes towards compliance. Many other claims may not express similar defiance: as studied by Bárd and Grabowska-Moroz (2020), certain statements accompanying non-compliance entailed denying or disguising the lack of enforcement of EU recommendations and rulings, without necessarily challenging the authority producing them. However, the declarations included in this database represent specific attitudes towards EU enforcement procedures, allowing for the examination of the article's argument, regardless of potential variations in behaviour across different domains. A second limitation is the exclusion of non-English domestic sources, which may result in a gap in identifying defiant rhetoric, particularly in contexts involving decentralised EU enforcement. Nonetheless, relying on English sources still offers sufficient valuable insight into defiant non-compliance for a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon to be gained.

III Findings

The following section presents the main findings of the article before discussing them in detail. Evidence has been found to support the four types of non-compliance identified by the categories; however, we have not found any defiant statements associated with the last one (although this may be due to research limitations, as will be explained below).

Non-Compliance With EU Commission Recommendations

A summary of actions under this category of non-compliance is provided below. Concerning Hungary, the Commission initiated 16 RoL-related infringement procedures during the period under review and referred 10 of these to the Court. In the case of Poland, the Commission instigated eight procedures, six of which progressed to the litigation stage. Taking forbearance as standard Commission's behaviour (Kelemen and Pavone, 2023), referral to the Court of more than half of the procedures for Hungary and all but two for Poland signals the lack of willingness to comply in the pre-adjudication stage of the procedure. Further, the Commission required interim measures in five of these cases and monetary fines in four of them, all concerning Poland.

In addition, the Commission activated the RoL Framework in 2016 against Poland and launched four recommendations during 2016 and 2017 following this decision. The non-compliance of the Polish government with these recommendations and the further deterioration of the concerns identified on them compelled the Commission to activate Art. 7.1 in December 2017. By contrast, the Commission never triggered the RoL Framework against the Hungarian government, and it was the European Parliament that launched Art. 7.1 against it in September 2018.

Finally, RoL funding conditionality has also been applied for both Warsaw and Budapest as a result of lack of compliance (Thinus, 2024). In June and December 2022, the Commission approved the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) plans for both Hungary and Poland. However, funds were not released within the timeframe covered by this article (until the end of 2022), as the Commission considered that these governments had not met the milestones related to the RoL. Nonetheless, it should be noted that Hungary received RRF payments in January 2024, when the Commission disbursed €140.1 million in grants as part of the pre-financing related to the REPowerEU funds. The Commission also released funds for Poland under the RRF in 2024, following the change of government. In the case of Hungary, the Commission also invoked the Conditionality Regulation in April 2022 and withheld Cohesion Funds (partly unblocked at the end of 2023), as it considered that Hungary had not fulfilled the horizontal enabling condition on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as regards judicial independence.

Non-Compliance With CJEU Rulings

The non-compliance history of the infringement cases is abstracted in Table 3.

| Date | Government | Topic | Infringement | Reference | CJEU | Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Hungary | Minority rights |

Asylum and return. Failure to comply with the judgment of the Court in Case C-808/18 |

INFR(2015) 2201 |

Case C-808/18 Case C-123/22 |

Refusal to comply (Case C-123/22 in progress) |

| 2017 | Hungary | NGOs | NGOs funding law | INFR(2017) 2110 | Case C-78/18 | Refusal to comply (ongoing, Art. 260 TFEU) |

| 2017 | Hungary | Academic freedom | Higher education law | INFR(2017) 2076 | Case C-66/18 | Refusal to comply (ongoing) |

| 2017 | Poland | Judicial independence | Amendment to the law on ordinary courts' organisation | INFR(2017) 2119 | Case C-192/18 | Refusal to comply (ongoing) |

| 2018 | Hungary | Minority rights | Stop Soros law | INFR(2018) 2247 | Case C-821/19 | Refusal to comply (ongoing) |

| 2019 | Poland | Judicial independence | Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court | INFR(2019) 2076 | Case C-791/19 | Refusal to comply (ongoing, Art. 260 TFEU) |

| 2020 | Hungary | Minority Rights | Non-compliance with EU acquis on asylum of Hungarian Act LVIII of 2020 | INFR(2020) 2310 | Case C-823/21* | Refusal to comply (ongoing) |

| 2020 | Poland | Judicial independence | Legislative changes affecting the judiciary (‘muzzle law’) | INFR(2020) 2182 | Case C-204/21* | Refusal to comply (ongoing) |

- * Cases ruled upon in 2023. These were included because they (i) were initiated in the timeframe discussed in this article and (ii) contribute to the understanding of the overall pattern, since they reveal a continued non-compliance trend.

The governments of both Hungary and Poland have refused to comply in eight cases out of the 13 RoL-related infringement cases, which were referred to and decided on by the CJEU during the period under review, identified by Hernández and Closa (2023). This is evidenced by the fact that several infringement proceedings are still ongoing despite the CJEU having ruled on them (several years ago in some instances). Moreover, the Commission has even initiated proceedings under Art. 260 TFEU in some cases. The Hungarian government has failed to comply in five cases, out of nine infringement proceedings referred to and decided upon by the CJEU related to the RoL under Fidesz's mandate. Similarly, the Polish government has failed to comply in three cases out of a total of four infringement proceedings referred to and decided upon by the CJEU concerning the RoL under the PiS mandate.

National Constitutional Courts' Adjudication Against EU Law and CJEU Authority

For Category 3, this article identifies three key instances in which national governments sought adjudication from their respective national courts regarding CJEU rulings and/or powers: two for Hungary and one for Poland. In 2016, Hungary's captured Constitutional Court ruled [Decision 22/2016 (XII. 5.) AB] that the national court itself could examine whether the EU's exercise of power violated human dignity, any other fundamental rights, Hungary's sovereignty or Hungary's constitutional identity. Based on this examination, the Court had the power to override EU law in the name of constitutional identity. Whilst this still moves within the classic ‘Solange’ doctrine, more important challenges occurred in 2021 when the RoL crisis intensified and the governments of Hungary and Poland requested that their Constitutional Courts adjudicate on the primacy of EU law.

In 2021, the Hungarian government sought the adjudication of its Constitutional Court to determine the compatibility of implementing CJEU rulings with the Hungarian constitution. The specific inquiry related to a CJEU decision on Viktor Orbán's asylum policy, whereby the CJEU urged Hungary to halt the practice of pushing back asylum-seekers to the Serbian side of its 2015 border fence without initiating a formal procedure. The Hungarian Constitutional Court addressed the issue of the primacy of EU law regarding national immigration law [Decision 32/2021. (XII. 20.) AB]. However, the Court refrained from directly challenging the CJEU by rejecting prior case law or directly contesting their primacy. The Hungarian government interpreted the decision as approval, declared that its migration policy would remain unchanged and asserted that the Constitutional Court ruling supported its existing policy.

In Poland, the challenge to the primacy of the CJEU centred around two significant cases decided upon by the Polish Constitutional Tribunal. These decisions followed inquiries from the Polish government that specifically addressed the constitutionality of regulations related to the judicial system and examined whether interim measures concerning the judiciary, granted by the CJEU, conformed to the Polish Constitution. In rulings dated 14 July (P7/20) and 7 October 2021 (K3/21), the Tribunal declared certain provisions of the EU Treaties incompatible with the Polish Constitution, explicitly contesting the primacy of EU law. The Tribunal asserted that the interim measures imposed by the CJEU interfered with the organisation of the Polish judiciary in an ultra vires manner.

Procedures and Legislation to Prevent Preliminary Rulings

Finally, the fourth category concerns both new legislation and/or judicial procedures that seek to prevent lower courts from issuing preliminary rulings. Requests for preliminary rulings from higher courts were excluded from this analysis. Some of these courts upheld the RoL vis-à-vis their governments at certain points in time, such as the Polish Supreme Court under the Presidency of Judge Małgorzata Gersdorf, who stopped the enforcement of the law ordering the early retirement of older judges and referred a question to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling in 2018. However, the independence of higher courts in both Hungary and Poland has raised serious concerns in recent years, as reflected in the Commission's annual RoL Reports, as well as in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights. Moreover, these higher courts have been involved in silencing lower courts through disciplinary proceedings, as will be discussed below. Their inclusion in the analysis would therefore provide limited information, as their involvement has mainly focused on hindering other courts from initiating requests for preliminary rulings.

Table 4 provides an overview of various cases in the period under analysis, several of which refer to disciplinary regimes enforced against judges. In line with the above, the table contains only instances of preliminary questions from lower courts.

| MS | Actor | Year | Case | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2018 and 2019 | Joined cases C-558/18 and C-563/18 | Disciplinary Regime |

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2018 | C-623/18 | Disciplinary Regime |

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2019 | Cases C-748 to C-754/19 | Disciplinary regime and powers of the Minister of Justice to appoint and dismiss judges |

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2020 | C-615/20 and C-671/20 | Disciplinary Regime |

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2021 | C-181/21 and C-296/21 | National Council for the Judiciary |

| Poland | Polish district/regional courts | 2021 | C-521/21 + C-647/21 and C-648/21 | National Council for the Judiciary |

| Hungary | Hungarian district/regional court | 2019 | C-564/19 | Disciplinary proceedings |

Whilst both governments have sought to hinder these courts from resorting to the CJEU, they have used different routes to do so. In Hungary, the (captured) Supreme Court ruled that one particular application (C-564/19) was unlawful and threatened the requesting judge with disciplinary action. Even though these actions were not effectively implemented, the threat had the effect of discouraging lower courts from seeking guidance from the CJEU in future cases. Adopting a much more explicit and radical stance, the Polish government sponsored a 2019 law, known as the ‘Muzzle Law’, which gave powers to the Disciplinary Chamber of Poland's Supreme Court to instigate disciplinary proceedings against judges who referred preliminary questions to the CJEU. In this case, the CJEU found that the law contravened EU law (INFR(2019)2076, C-204/21). In both countries, disciplinary procedures secured a robust implementation of these restrictive measures.

Defiant Claims

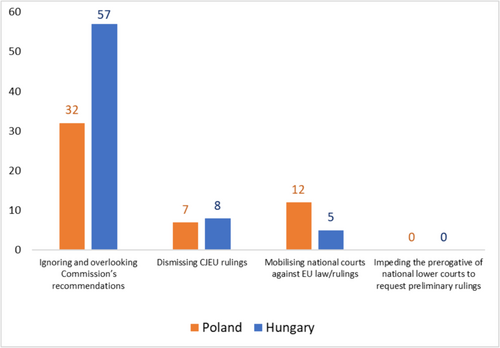

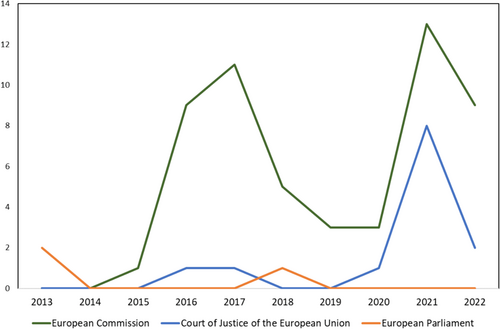

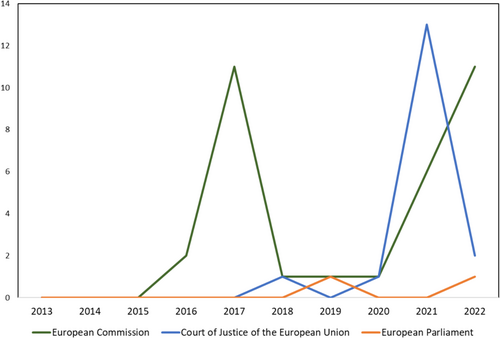

The graphs below present the findings concerning defiant claims associated with the four types of actions described above. The Hungarian government made 70 statements (58% of the total identified) and the Polish government 51 (42%). Figure 1 provides a breakdown by national government and year.

Source: Developed by the authors.

The graph above shows a significant increase in defiant claims in the last 2 years under review and reveals that a very similar pattern has been followed by both governments over time, although the Hungarian government has been slightly more critical of EU institutions' enforcement actions. Figure 2 shows which types of actions have been the subject of these defiant claims.

Source: Developed by the authors.

The most frequent defiant claims made by both the Polish and Hungarian governments are associated with actions of non-compliance with the Commission's guidelines and recommendations. In the case of the Polish government, the second most frequent type of defiant non-compliant behaviour involved mobilising national courts to challenge the role of the CJEU as the sole final interpreter of EU law. Meanwhile, in the Hungarian case, the second most common type of defiance accompanies non-compliance with CJEU judgments. Interestingly, no claims related to the fourth type of action, that is, questioning or impeding national courts' right to refer preliminary questions to the CJEU, were found. Although it is important to note related cases of government attacks on individual judges, such as the repeated attacks on several Polish judges such as Igor Tuleya or Beata Morawiec, who were suspended by the Supreme Court's Disciplinary Chamber, we have not found declarations related to these cases that directly impinge on the right of national courts to request preliminary rulings. However, a salient selection bias may be in operation here: this kind of action happened almost exclusively at the domestic level; that is, it targeted decentralised authorities of EU law enforcement. Hence, claims may have predominantly happened at the national level and in the vernacular language. This research has not delved into domestic sources in languages other than English, and this may account for this vacuum, which future research could clarify.

Insufficient evidence was found to argue that there was a quantitatively significant difference in the categories of types of defiant non-compliance attitudes displayed between the Hungarian and Polish authorities, based on the data and the Fisher's exact test performed (see Appendix S2). Nevertheless, based on the analysis presented in the previous sections, a qualitative assessment could be made, which found that the Polish government's attacks on the judicial authorities have been more profound. First, Polish authorities have explicitly challenged the primacy of EU law. The Polish Constitutional Court explicitly contested primacy and legitimised explicit governmental challenges to this principle, including statements by Prime Minister (PM) Mateusz Morawiecki that ‘there is no doubt about the primacy of Polish constitutional norms over other legal norms’ (observation 58, Appendix S1) and that ‘this principle is not unlimited. In each of our countries, primacy is maintained by the Constitution’ (observation 79, see also 80 and 81). On the contrary, Hungary avoided ‘an immediate legal battle with Brussels after the country's constitutional court stopped short of disputing the primacy of EU law’ (observation 88, claimed by the Minister of the PM's Office Gergely Gulyas; see also observation 89 by Justice Minister Judit Varga). Second, the efforts by the Polish government to prevent national courts from requesting preliminary rulings were also more incisive and openly launched than those of the Hungarian government, as discussed in the previous section (although it has not been possible to empirically prove that the latter attitude can be fully considered a case of defiant non-compliance in this article).

Finally, Figures 3 and 4 show defiant statements targeting the different EU institutions made by each of the governments (Hungary and Poland) over time:

Source: Developed by the authors.

Source: Developed by the authors.

Figures 3 and 4 (as well as Figure 2) show that defiant claims targeted mainly the Commission and the CJEU, both of which concentrate the EU's enforcement capacities. Given the active role of the EP in RoL dossiers, surprisingly, it attracted less defiance in the claims made by these governments during the period under study. The Council was conspicuously absent. In line with this institutional concentration, these governments targeted mainly Commission recommendations and warnings. Given that the Commission's actions are numerically much higher than those of any other institution, the pattern does not provide a distorted view of non-compliance actions. In both cases, instances of pronounced defiant behaviour by the Hungarian and Polish governments coincided with the key moments of identified non-compliance mentioned earlier. Insufficient evidence was found to claim the existence of a significant difference in the institutions targeted by the defiant non-compliance behaviour displayed by the Hungarian and Polish authorities, as indicated by the data and the Fisher's exact test performed (see Appendix S2).

IV Discussing Defiant Non-Compliance

As a law-based community, the EU expects member states to engage in voluntary compliance with its rules, which they agreed to follow at the time of accession. The behaviour of the Polish and Hungarian governments has clearly challenged the EU premise, as it has gone beyond ordinary disagreement; rather, it has questioned not only the content but also the authority of the Commission's recommendations and the CJEU's rulings, coupled with the use of strong defiant rhetoric. This article has shown that defiant non-compliance consists of at least three different types of actions matched by an equally defiant rhetoric: ignoring EU recommendations and warnings; non-compliance with the CJEU's rulings; and questioning the role of the CJEU as the sole final interpreter of EU law. Whilst evidence of a defiance discourse for the fourth category (questioning national courts' right to raise preliminary questions) is inconclusive, its potential significance warrants further analysis in future research using national sources in languages other than English.

Defiant non-compliance reached its highest points in 2017 and 2021. Notably, the decrease observed between 2018 and 2020 coincided with a decline in the Commission's enforcement actions, as indicated in the literature (Hernández and Closa, 2023). Therefore, the patterns reflected in the data seem to align with EU enforcement actions over the years; that is, defiant non-compliance seems to respond logically to patterns of enforcement activity.

Despite the Hungarian government experiencing a comparatively more lenient enforcement approach from the Commission over the years than its Polish counterpart (i.e., several RoL enforcement instruments, such as the RoL Framework or Art. 7.1 were instigated by the Commission against Warsaw and not Budapest), its defiance harshly targeted this institution. The frequent Commission's utilisation of infringement actions against the Hungarian government may explain this. This suggests that defiant non-compliance may not be exclusively linked to the use of enforcement tools designed for safeguarding fundamental values but could be a more extensive trend affecting the broader EU law enforcement framework; that is, similar behaviour may manifest in other policy domains beyond the RoL, as long as extreme cases of non-compliance occur within these policy areas. By ignoring the Commission's recommendations and warnings, the governments of PiS and Fidesz called into question the management approach to compliance, as soft actions aimed at dialogue with the offending government (i.e., the pre-litigation stage of the infringement procedures) proved ineffective and met with opposition.

Comparatively, the Polish government's challenges to judicial authorities, especially the CJEU, have been qualitatively more intense than those of the Hungarian executive. This underscores the perception of judicial institutions as having the capacity to compel compliance and, consequently, posing a threat to the Polish government's institutional transformations. The shift from the CJEU to national courts as the ultimate interpreters of EU law is thus more pronounced in the Polish case.

The fact that most of the defiant claims have been directed at these two institutions (i.e., Commission and CJEU) shows that they are indeed perceived as the enforcers of EU core values. This reflects a perception that the Council plays a less active role in the field of RoL protection. However, this contrasts with the central role the Council plays in enforcement, particularly considering its ultimate authority in deciding on Art. 7 (although it has proved impossible to enforce it when more than one member state has problems of RoL compliance) and its crucial function in monitoring non-compliant governments through hearings. The fact that the challenging claims were focused on the Commission and the CJEU suggests a divergence in the perception of the roles played by these institutions regarding RoL enforcement in the eyes of those contesting EU norms and values. Targeting the Council would make less sense, given that the majority required makes it difficult for the Council to act forcefully on RoL issues (at least until the majority requirements were changed under the Conditionality Regulation in 2022). Additionally, it also indicates that the Polish and Hungarian governments may find it costlier to challenge the authority of the Council, of which they are members and where open contestation is rare.

Finally, the similarities identified in terms of the type of defiant behaviour and the institutions targeted by the Polish and Hungarian governments also reinforce the idea that defiant non-compliance is one and the same phenomenon, as shown in this article. Additionally, there are similarities in the underlying factors leading to defiant non-compliance in both cases. Ideological factors explain the emergence of this phenomenon, as anticipated in the literature (Bugaric and Kuhelj, 2018; Coman and Leconte, 2019; Pirro and Stanley, 2021).

Conclusion

Examining defiant non-compliance in the RoL crises related to Hungary and Poland challenges conventional perspectives on non-compliance, which typically attribute it to factors such as a lack of capacity or incentives to deviate. It also reveals some critical implications for the functioning of the EU: the absence of compliance and the deliberate and persistent defiance of enforcing mechanisms and authorities not only hampers the EU's legal framework, but also poses a significant threat to its core principles and values. This has critical consequences for the role of Eurosceptic governments within the EU. For instance, unlike the United Kingdom during Brexit, where, despite critical rhetoric, compliance with EU recommendations and rulings remained intact, the behaviour of the Hungarian and Polish governments indicates that a more challenging dynamic is at play. Whilst the United Kingdom ultimately opted for the activation of the ‘exit’ option (Art. 50 TEU) and left the EU, defiant non-compliance in Hungary and Poland directly erodes the fundamental premise of the EU as a community bound by the RoL. Defiant non-compliance also raises concerns about the resilience of the EU's RoL framework and its ability to address and rectify non-compliance effectively. The spread of this form of resistance to other governments within the EU holds the potential to undermine the cohesiveness of the Union and diminish its ability to uphold fundamental principles. Finally, evidence has so far shown the defiant non-compliance associated with RoL issues. Further comparative research could trace whether this variety of defiant non-compliance appears in other issue areas. This agenda is particularly relevant, since current enforcement mechanisms have only partly corrected violations of EU law.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the JCMS anonymous reviewers and editors who provided excellent comments on the article. The authors also acknowledge support of the publication fee by the CSIC Open Access Publication Support Initiative through its Unit of Information Resources for Research (URICI). The authors gratefully acknowledge support received from the “Institutional design for enforcing Rule of Law compliance in the EU” (InDeComply) Project (Grant PID2021-122448NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). One of the authors also acknowledges support received from Grant FPU20/01664 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.