The (De-)Europeanization of the Political Class in the European Parliament: A Longitudinal Analysis of Members of the European Parliament's Career Patterns (1979–2019)

Abstract

This article presents a systematic empirical analysis of the career patterns of all 3634 members of the European Parliament (MEPs) who served in the European Parliament (EP) over the last 40 years (1979–2019). It explains how changes in the EP's structure of opportunities have shaped the development of MEPs' career patterns. First, we show that the development of a European political class is not a recent trend but that this process took place in the early days of the EP (as soon as in the 1984–1989 term), albeit with variance across political groups of the European Parliament (EPGs) and Member States. Second, we observe that the transformation of party systems and electoral volatility have been questioning the existence of the European political class. Overall, we conclude that legislative institutions are only as strong as the individuals who are called to serve them. Recent rises in the EP's turnover could ultimately undermine the EP's formal policy-making capacity in the middle and long terms.

Introduction

The incremental empowerment of the European Parliament (EP) is one of the most notable evolutions in the democratic functioning of the European Union (EU). The effective influence of the EP in EU policy-making processes does not merely depend upon its formal powers. It also depends upon the profiles of members of the European Parliament (MEPs) that serve in the institution (Daniel and Metzger, 2018). This requires MEPs with European-oriented political careers who are ‘willing to exercise and extend powers granted to their assembly’ (Scarrow, 1997, p. 253). By contrast, the EP's formal powers can be undermined when the assembly is predominantly populated by MEPs with domestic and short-term ambitions. Along with the institutional empowerment of the EP, several studies have, therefore, investigated the development of a European political class. Scarrow (1997) was one of the first authors to outline the emergence of European careerists. Whilst recent studies tend to confirm Scarrow's initial findings (Beauvallet-Haddad et al., 2016; Bíró-Nagy, 2019; Daniel, 2015; Verzichelli and Edinger, 2005; Whitaker, 2014), the development of a European political class remains largely unknown on two accounts. On the one hand, previous studies are limited (1) to single-country case studies and (2) to specific legislative terms, whilst (3) they are dominated by methodological nationalism (i.e., regional offices are neglected). On the other hand, the scholarship is still missing a study of the factors explaining the orientation of MEP's career over time and across levels.

The goals of this article are twofold. First, empirically, the article provides the first comprehensive longitudinal description of the political careers of all 3634 MEPs (EU-28) who ever served in the EP (1979–2019). Second, we demonstrate how the changing EP's institutional opportunity structure shaped MEPs' career orientation. That is to say, we show that evolutions in the EP composition are to be explained by the transformations of its broader institutional and political environment in terms of ‘attractiveness’, ‘availability’ and ‘accessibility’ of European offices [Borchert's (2011) three A's conceptual framework].

Our contribution brings new insights to the literature, including some concerns about the prospective evolution of the EP as an institution. First, our study confirms the development of an ever more professionalized European political class in the EP. Despite the second-order nature of the European elections, this professionalization occurred faster than what is usually presented in the literature. Against the ‘traditional view’ (Hix and Høyland, 2011, pp. 54–55), the EP has never been a mere ‘retirement home’ or a simple ‘training arena’ before a national career. The professionalization of MEPs' European careers has been observed since the early days of the EP. Yet, our results also show that this process of professionalization is not uniform. There is important variance across countries (weaker professionalization for most central and eastern Member States) and party groups [stronger professionalization for the European People's Party (EPP) and Socialist groups]. Second, our results show that the development of a European political class has been reinforced by the EP empowerment as well as by electoral regulation restricting domestic career incentives (e.g., electoral regulation about dual mandate). Finally, our results suggest that recent transformations in European party systems might have started jeopardizing the core of the European political class in a context of increased party fragmentation and Euroscepticism since the early 2010s.

The article is structured as follows: the first section provides an overview of the scholarship on MEPs' career patterns and introduces a new categorization to address current limits. Sections II and III present the dataset and provide a description of our empirical analysis. Section IV demonstrates how changes in the institutional structure of opportunity affect the evolution of the EP composition. Finally, the article ends by discussing the implications of our findings for the development of the European political class in the future.

I European Political Class and MEPs' Career Patterns: Refining Existing Categories

According to the German school of thought (Borchert, 2003; Stolz, 2003; Von Beyme, 1996; Weber, 1946), professionalization is the primary driver behind the development of a political class. As per Weber's (1946) seminal words, ‘politicians who “live for politics” were gradually replaced by professionalized politicians who also “live of politics”’. This entails a political class acting collectively to ‘try to form and reform democratic institutions according to their class interest’ (Stolz, 2003, p. 224). Most European democracies have experienced such processes of professionalization of politics, albeit to varying degrees across countries and over time (Best, 2007; Borchert, 2003; Dodeigne, 2018). Building on this literature, we can conceptualize the development of a European political class along two main dimensions. On the one hand, we assess the degree of professionalization of MEPs by considering the duration of offices served in European and domestic political arenas (professional differentiation). On the other hand, we distinguish the career orientations of MEPs by examining at which governance levels they served (territorial differentiation).

Table 1 presents four types of structuration of the political class according to these two criteria. MEPs with European territorial orientation and professionalized careers are part of the ‘European political class’. On the opposite, MEPs who have predominantly developed professionalized careers in domestic politics are part of the ‘domestic political class’. Those with professional careers across both arenas are part of a single ‘integrated political class’: the latter evolves in a multilevel political system without territorial delimitation and hierarchy. Finally, MEPs serving offices for a very limited period without clear territorial orientation are labelled as ‘political short-termers’.

| Structure of the political class | Territorial differentiation | Professional differentiation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | European | Domestic | European | |

| European political class | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Domestic political class | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Integrated political class | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Political short-termers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The Structuration of the Political Class in the EP According to Career Patterns

At the European level, with the progressive institutional empowerment of the EP, several scholars have assumed the development of a European political class. Even though European scholars do not always explicitly refer to the concept of political class, they developed career patterns that build on the territorial and professional differentiation presented in Table 1. In this regard, Scarrow's (1997) seminal study distinguished three main career paths. Her first category of ‘European careerists’ forms the core of the European political class. These MEPs present a ‘long and primary commitment’ to the EP whilst ‘willing to exercise and extent powers granted to their assembly’ (Scarrow, 1997, p. 253). The European political class's interest is distinct from that of the national political class, which turns the European level into a political arena in ‘its own right’. Her second category covers the ‘political dead-end’, that is, politicians who served in the EP only for a short period of time without any other mandate (at any tiers of government). Those MEPs must be considered as political amateurs as they are not experiencing a process of professionalization at the European level (or any other tiers of government). Her third career patterns are the ‘stepping-stone’ MEPs, that is, they seek to move up to national politics after their time in the EP. Those MEPs remain predominantly fuelled by domestic ambition and belong to the domestic political class: the EP is nothing more than a mere entry point into politics before moving to the national arena.

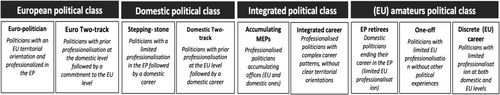

In the last few years, these three career paths have been further discussed in the literature. Scholars have contributed not only to extend the geographical and time scopes of Scarrow's study, but they have also refined some of her original categories. Despite the rich and important contributions made by this scholarship, the definition and operationalization of current MEPs' career patterns tend to overlook the complexity and sequence of positions served in the European multilevel political systems. Existing categories in the scholarship do not sufficiently reflect the specific combination of domestic and European offices that shape specific career patterns. Our goal is, therefore, to refine the existing typologies to describe MEPs' career orientation according to the four categories structuring the political class in the European multilevel systems (see Table 1). Our new typology is presented in Figure 1.

Notes: EP, European Parliament; EU, European Union; MEPs, members of the European Parliament.

First, the European political class covers the so-called ‘European careerists’. The latter has attracted most attention from scholarship, as they reflect the strongest evidence of the development of a European political class. The literature tends to point out the stabilization of such European ‘long-termers’ (Bíró-Nagy, 2016; Salvati, 2016; van Geffen, 2016; Verzichelli and Edinger, 2005; Whitaker, 2014). Within this category, Verzichelli and Edinger (2005) introduced a distinction between ‘Euro-politicians’ (i.e., MEPs without prior political experience serving in the EP over multiple mandates) and ‘Euro-experts’ (i.e., politicians with a significant domestic career who subsequently conduct a professional career in the EP). Whilst we conceptually agree with the Verzichelli and Edinger (see also Salvati, 2016) classification, we prefer using the label ‘Euro two-track’ rather than ‘Euro expert’. This avoids any confusion over the term ‘expert’.

As part of the domestic political class, we consider MEPs with limited professionalization within the EP but with a strong domestic territorial career orientation. Some scholars also labelled them as ‘stepping-stone’ MEPs. As outlined by Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir (2007), this label includes MEPs using the EP as an arena of professionalization before domestic politics. Some also used the EP as a ‘transition’ between two domestic mandates (see also Bíró-Nagy, 2019; Scarrow, 1997). Finally, the domestic political class also includes MEPs with European professionalized careers who subsequently pursue their career in domestic politics. We label them ‘domestic two-track’ MEPs (i.e., after a career at the European level, they are now fully committed to domestic politics). In the political short-termers category, we include three types of career paths: ‘EP retiree’, ‘one-off MEPs’ and ‘discrete career’. These MEPs have in common a weak professionalization at the European level. Previous studies already highlighted the existence of a relatively small – albeit stable – share of ‘EP retirees’ (i.e., MEPs ending their career in the EP; see Scarrow, 1997; Whitaker, 2014). Moreover, van Geffen (2016) also identified a category of MEPs that steadily increased over time, namely, ‘one-off’ MEPs. The latter did not have any political career before or after serving in the EP; they merely served in the EP for a very short period. Then, the ‘discrete career’ pattern is composed of MEPs with limited professionalization at any level (i.e., an ‘ephemeral career’ according to Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir, 2007). Finally, in the integrated political class, we identify two career paths: ‘accumulating MEPs’ and ‘integrated career’. These MEPs present a strong degree of cross-level professionalization, but without clear territorial orientation. On the one hand, it covers MEPs with dual mandates at both European and domestic levels. This type of career pattern is overlooked in the literature (but see Navarro, 2013), whilst it could directly affect MEPs' parliamentary behaviour because of domestic interests [e.g., MEPs deviating more systematically from their Political groups of the European Parliament (EPGs) voting lines]. On the other hand, this integrated political class includes MEPs with complex career sequences across levels (e.g., European ➔ national ➔ European ➔ national ➔ regional), but without clear territorial orientation.

II Data and Operationalization

The literature on MEPs' careers is predominantly restricted to specific periods (but see Beauvallet-Haddad et al., 2016) and often country specific (e.g., Beauvallet and Michon, 2016, on French MEPs; Real-Dato and Alarcon-Gonzalez, 2012; Real-Dato and Jerez-Mir, 2007, on Spanish MEPs; Kakepaki and Karayiannis, 2021, on Greek MEPs; or Bale and Taggart, 2006; Bíró-Nagy, 2016, 2019, on central and/or eastern countries). In this contribution, we seek to offer the first comprehensive analysis of the evolution of all MEPs' career patterns in the EP (1979–2019).

The ‘Evolv'EP Project’ Dataset

Our empirical analysis is based on an original dataset of all 3634 MEPs who served once in the EP over the first eight legislative terms (1979–2019). The dataset builds upon existing biographical information on MEPs' careers for the period 1979–2011 (Høyland et al., 2009). It was subsequently updated to cover the remaining period of analysis (2011–2019). Moreover, the dataset was completed with information related to offices served in legislative and government institutions in their national country. For the latter, we rely on information published by official institutions and biographies available online. All European and domestic offices are recorded by the number of months served in the respective institutions. Because a significant number of Member States have federal political systems in which regional tiers have a high degree of authority (see Hooghe et al., 2016), the dataset also includes information on subnational legislative and executive offices for seven Member States (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK). Former studies have mostly ignored the inclusion of subnational offices, despite the growing importance of this level of government in modern politics (Schakel and Jeffery, 2013; Toubeau and Massetti, 2013). This has been identified as a critical limit in recent scholarship (see Høyland et al., 2019; van Geffen, 2016; Whitaker, 2014). As a matter of fact, MEPs from federal and regionalized countries represented three quarters of all MEPs until the late 1990s (73% at the fourth legislative term) and still represented a majority of all MEPs in the eighth legislative term (54%). Furthermore, we observe that 25.4% of MEPs originating from federal or regionalized countries have served at the regional political level before or after their term(s) in the EP. As we show below, our inclusion of regional offices brings substantially new insights into the relationship between domestic and European levels (Daniel, 2015).

Operationalization of Career Patterns

We now discuss the operationalization of MEP's career patterns discussed above. Following Scarrow (1997), ‘Euro-politician’ is operationalized as MEPs conducting their entire career in the EP during at least 1.5 terms in the EP (i.e., about 8 years), whilst ‘Euro two-track’ are politicians with prior domestic experience (i.e., at least one domestic term) before serving a career in the EP for at least 1.5 terms. For the domestic political class, ‘stepping-stone MEPs’ include politicians serving in the EP for a limited period (i.e., less than one term) followed by a longer career at the domestic level (i.e., we also use about 8 years as a baseline, which covers at least two domestic terms in most domestic legislatures). ‘Domestic two-track’ politicians served at least one term in the EP, but their main territorial orientation remains primarily domestic, where they develop a professionalized career (i.e., at least two domestic terms). ‘EP retirees’ are operationalized as MEPs with previous domestic political experience (i.e., at least two domestic terms) and serving in the EP for no more than 1.5 legislative terms before ending their political career. ‘One-off MEPs’ cover MEPs serving less than 1.5 terms in the EP without any other political mandates before or after their EP mandate. ‘Discrete’ MEPs have a short political career at both the EU and domestic levels (i.e., at least 1.5 EP terms or 2 domestic terms, about 8 years). Finally, ‘accumulating MEPs’ are politicians who had dual mandates during their service in the EP (at least 12 months of accumulation with a domestic office).

Robustness checks have been conducted to confirm the empirical conclusiveness of our analytical categories. For that goal, we used stricter criteria, that is to say, we increased the requested duration of the European career to test the sensitivity of our results (using 2 terms instead of 1.5 terms as the main criterion). In addition, we lowered the criteria for domestic orientation (slightly below two completed domestic terms, with 7 years of experience being sufficient to label an MEP with a professionalized domestic career). Overall, not only are the changes introduced relatively limited (hardly 7.5% of all 3634 MEPs are affected), but, furthermore, they do not noticeably affect the distribution across our categories. 1 In other words, our findings are highly consistent.

III Describing MEPs' Career Patterns: The Early Development of the European Political Class in the EP

In this section, we present the evolution of the political classes in the EP following our four main categories (see Figure 1), namely, the European political class, the domestic political class, the integrated political class and the short-termers.

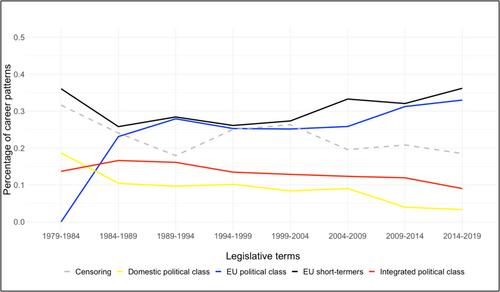

The Rapid Emergence of a European Political Class in the 1980s

Our results show that the European political class emerged rapidly and stabilized as soon as the second legislative term (1984–1989). This coincided with the development of political short-termer MEPs in similar proportions, though (see Figure 2). From 1979 until the late 1990s, these two categories covered the majority of MEPs serving in the EP. Since the early 2000s, these two profiles of MEPs have increased to reach 69.2% in the 2014–2019 term. By contrast, we observe a structural decline – at a slight pace over time – in the share of domestic orientation and integrated career patterns. Whilst the domestic and integrated political classes represented 24% of MEPs in the early 1990s, they dropped to 12% in the eighth legislative term. Finally, the proportion of MEPs who cannot be classified (i.e., censored data because of an unterminated career at the end of a legislative term) is constant over time (between 18% and 27%, the first term evidently excepted).

Notes: ‘censoring’ indicates members of the European Parliament with an unterminated career at the end of a given legislative term. Their career orientation cannot be classified according to our classification of career patterns. EU, European Union.

Compared with other multilevel political systems, the EP can be considered as an electoral arena with limited barriers to domestic institutions. There are relatively strong interactions between European and domestic electoral arenas, as in Belgium or in Spain (Dodeigne, 2014, 2018; Stoltz, 2011). Indeed, amongst all 3634 MEPs who served in the EP, 29% have former experience in domestic politics before their EP mandate (‘Euro two-track’, n = 349), during their EP mandate (‘accumulating MEPs’, n = 411) or after their mandate (‘domestic political class’, n = 429). 2 In this respect, the EP does not show evidence of a clear hierarchical structure between tiers of government, such as in the United States, where ambitious politicians move from state legislatures upwards towards the Congress (Schlesinger, 1966) or downwards towards the substate level, such as in Brazil (Samuels, 2003). One thing is certain, though: the EP clearly diverges from other multilevel democracies such as Canada and the UK, where level-hopping movements across tiers of government are extremely rare.

Interestingly, our study offers a rather different understanding of the effects of federalization on the kinds of interactions between the European and domestic arenas. Contrary to Daniel's (2015, p. 69) findings, MEPs from unitary states are not more likely to present a career pattern with domestic ambition. Our descriptive statistics show that 9% of MEPs from unitary states pursue a domestic career, whilst there are 14% in federal and regionalized Member States. Our diverging results can be explained by the fact that we include regional offices (and note merely national offices) to monitor domestic ambition. 3 Finally, descriptive statistics at the individual level confirm that MEPs with regional experience are clearly more likely to display domestic ambition (19%, compared with 9% with national experience only). Likewise, MEPs with regional experience present much more integrated career paths (12%, compared with 6% with national experience only). By contrast, MEPs with a regional pattern contribute less to the European political class (13% in comparison to MEPs without such regional experience, which account for 29%). Our findings thus reveal that the nature of interactions between European and national arenas is relatively hermetic, whilst European and regional arenas are much more integrated. Future research should consider whether the degree of institutionalization and professionalization of (newly established) regional parliaments in Europe is the main cause of this effect.

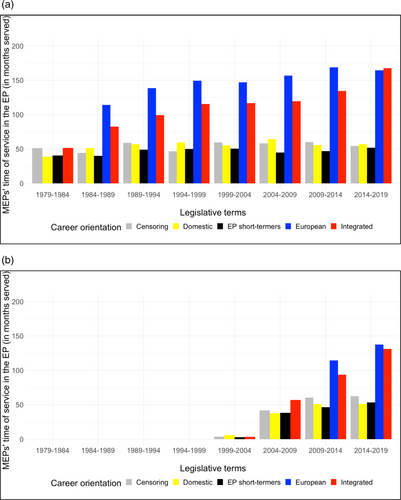

Professionalization of the European Political Class

Along with the increasing proportion of MEPs with European orientation, we observe that the degree of professionalization of the European political class has also substantially extended (Figure 3a,b). Whilst the average time of service of European-oriented MEPs was 114 months in the second legislative term, it increased to 169 months in the seventh legislative term (i.e., almost three full legislative terms served, totalizing 14 years). Compared with national legislatures, European-oriented MEPs are amongst the most professionalized parliamentarians across the world (Matland Richard and Donley, 2004; Whitaker, 2014). The professionalization of the European political class confirms Scarrow's (1997, p. 261) initial intuition about a self-reinforcing trend. Those European-oriented MEPs developed greater institutional know-how and policy expertise and enjoyed greater access to influential resources in the EP (van Geffen, 2016; Whitaker, 2014). In other words, they increased their capacity to act as a collective actor to make a difference in the EU decision-making procedures.

Notes: Panel (a) presents MEPs' career duration for all Member States that joined the EU (Central and Eastern Europe) between 1952 and 2004. The UK's delegation of MEPs is included until the latest term. Panel (b) presents MEPs' career duration for all Member States that joined the EU (Central and Eastern Europe) from 2004 (i.e., from the end of the fifth legislative term) until the present day. EP, European Parliament; MEPs, members of the European Parliament.

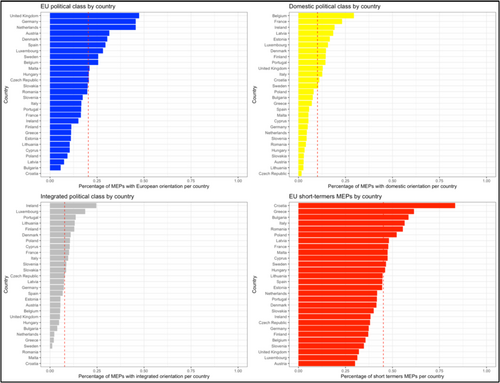

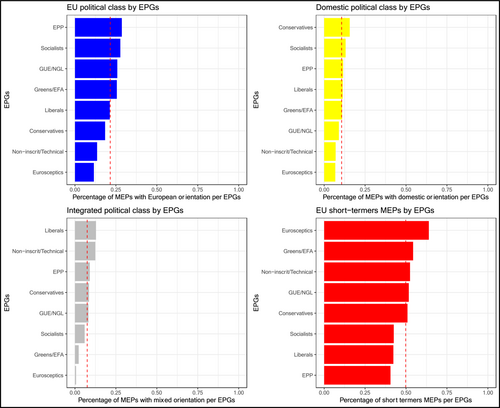

Cross-Country and EPG Variation of the European Political Class

The development of the European political class is far from being a uniform trend, though. Our findings outline that some Member States and EPGs are the main driving forces behind it (Figures 4 and 5). First, we observe that some countries are large contributors to the European political class. Whilst the average percentage is 20.4% per country, the UK, the Netherlands and Germany are significantly above with almost 50% of European-oriented MEPs (i.e., respectively, 47%, 46% and 46%). Other delegations are much lower; six other countries from the EU-15 (i.e., Austria, Denmark, Spain, Luxembourg, Sweden and Belgium) are between 22% and 32%. On the other hand, 10 of the 13 countries that joined the EU after 2004 are below average (the only exceptions are Hungary, Malta and the Czech Republic). Interestingly, two of the largest founding countries (i.e., Italy and France) are also below average, with hardly 17% of their MEPs being part of the European political class. As a mirror effect, we also find that the countries with more European-oriented MEPs also tend to have lower proportions of EU political short-termers as well as domestic-oriented MEPs (with some exceptions such as Belgium, Denmark and Luxembourg). The analysis also outlines that some countries (such as Ireland) stand out in the integrated political class: they were often the most flexible in terms of regulation for accumulating national and European offices (before the Council decision of 25 June 2002, applicable for the 2004 EP elections and in 2007 for Ireland).

Notes: EU, European Union; MEPs, members of the European Parliament.

Notes: EFA, European Free Alliance; EPGs, Political groups of the European Parliament; EPP, European People's Party; EU, European Union; GUE/NGL, Gauche unitaire européenne/Nordic Green Left; MEPs, members of the European Parliament.

Second, we observe that the two largest EPGs are, unsurprisingly, the groups where the European-oriented MEPs are the strongest, whereas the short-termer MEPs are amongst the lowest. The EPP and the Socialists, respectively, have 29% and 27% of European-oriented MEPs in their ranks (the average is 21%). Likewise, the EPP has the lowest (41%) and the Socialists the third lowest (42%) proportion of EP short-termers (the average is 50%). We observe a similar pattern for the Liberals – albeit to a lesser extent – with more EU-oriented MEPs and lower short-termers than the average. In contrast with influential EPGs, Eurosceptic MEPs present an almost perfectly inverse picture: they are overrepresented in the short-termers category (64%) and underrepresented in the European-oriented career patterns (12%). Futhermore, another pattern is observable for the Greens and the Radical Left: these groups both contribute to the European political class and to the EP short-termers, which illustrates the difficulty for these groups to maintain their electoral performance over electoral cycles. Finally, the Conservatives and the technical group tend to have an in-between situation where deviation from the average percentage is milder and not systematic across career patterns.

IV Explaining the Evolution of MEP's Career Patterns: Attractiveness, Availability and Accessibility of the European Offices

We now seek to explain the evolution of MEPs' career patterns as a consequence of the transformations of the EP's political and institutional opportunity structure. 4 For that goal, we rely on Borchert's (2011) three A's framework. His framework builds on Schlesinger's (1966) seminal contribution, but it furthermore specifies the effects of institutional and political specificities attached to European political systems. In this respect, the systematic application of the three A's framework permits to tackle some factors overlooked in the current literature (e.g., effects of the dual mandates in terms of availability of seats). In terms of data analysis, we should underline that we cover our entire population of interest (we included all MEPs who ever served in the EP). Any changes in the EP composition reflect, therefore, ‘significant’ changes in the EP composition. Our goal is to verify whether these significant changes are substantial in nature and whether these changes follow variations in the broader EP structure of opportunities. If this is the case, we can then provide strong pieces of evidence that specific institutional and political features of the EP attract distinct profiles of MEPs.

The Rising Attractiveness of the EP: An Arena for Professionalized Careers

Attractiveness is understood as the interest that a political arena triggers amongst potential aspirants to office (Borchert, 2011). In this regard, the incremental empowerment of the EP in terms of its legislative, budgetary and scrutiny roles is a central evolution in the democratic functioning of the EU (e.g., Hix and Høyland, 2013; Meissner and Schoeller, 2019; Rittberger, 2012; Rittberger and Schimmelfennig, 2006). Since 1957, the EP's legislative role has evolved from consultation to co-decision, whilst its policy scope – including the budget – has been extended through recent treaties (De Gardebosc, 2019; Mény, 2009; Shackleton, 2017). This is also observed in the greater role of the EP regarding the investiture of the Commission (Rittberger, 2012) and, more recently, regarding the election of the president of the Commission (Christiansen, 2016; Gattermann et al., 2016; Hobolt, 2014). Moreover, the attractiveness of the EP was reinforced in terms of financial retribution. Before 2009, there were large disparities between MEPs as they received a salary comparable to that of a national parliamentarian from their country (Daniel, 2015). Since the adoption of a single statute for its members (2009), all MEPs are now entitled to the same salary. In practice, there was an increase for almost all parliamentarians 5, especially for MEPs originating from central and eastern countries.

In this context, we verify that the formal empowerment of the EP directly shaped MEPs' careers by boosting the recruitment of professionalized members of the European political class (see also Beauvallet-Haddad et al., 2016; Bíró-Nagy, 2019; Daniel, 2015). Our results are, however, more nuanced, with two main conclusions. First, our results show that the emergence of a European political class was a rapid phenomenon that took place as early as the second legislative term. This indicates that it was not an incremental process that followed the growing empowerment of the EP over treaty changes. 6 Yet, we still find pieces of evidence that the rising attractiveness of the EP substantially affected MEPs' career orientation. On the one hand, we observe a notorious structural decline of the domestic political class (from 19% to 3% over the eight legislative terms) as well as of the integrated political class (from 17% to 9%). On the other hand, the core of this European political class has increasingly professionalized in terms of time of service (see Figure 3a,b). Overall, we can conclude that the growing attractiveness of the EP contributed to the development of a European political class, along with a decline in MEPs belonging to the domestic and integrated political classes.

This development of the European political class varies, however, greatly across EPGs. The two largest EPGs (EPP and Socialists) are overrepresented in this category, whilst the Eurosceptics group and, to a lesser extent, the technical groups are overrepresented in the short-termers category. The Liberals, the Greens and the Radical Left occupy an intermediary position. One explanation of this trend relates, here again, to the attractiveness of MEP positions in terms of positions of influence (see Aldrich, 2018). As the EP empowered, some EPGs accessed greater resources and became more influential in the EP (i.e., the Socialists and the EPP were holding an absolute majority until the 2014 elections, inclusive). By contrast, other groups remained only pivotal actors (e.g., the Liberals and the Greens, and arguably the Conservatives in most recent terms), if not marginalized and excluded from most of the EP's decision-making processes (i.e., the Radical Left, the Eurosceptics and the technical groups).

Availability of Seats in the EP: A New Opportunity for Politicians

The availability of seats in the EP relates to the number of seats available for which a candidate can compete (Borchert, 2011). Following the successive EU enlargements and treaty reforms, the size of national delegations sent to Brussels and Strasbourg was modified on several occasions. Yet, changes in the proportion of seats remain relatively limited (Salm, 2019; Salvati, 2016). Seat redistribution could only marginally impact career orientation. The most important institutional evolution concerns the use of dual mandates, that is, MEPs accumulating offices at the EU and national levels. This practice was common in the early days of the EP (Beauvallet-Haddad et al., 2016; Navarro, 2013). In 2002, a Council decision had banned the accumulation of national parliamentary office whilst serving in the EP from the 2004 European elections onwards (except for the opting-out provisions until 2007 for Ireland and 2009 for the UK). This is a decisive evolution in the institutional structure that explains some changes in MEPs' career orientation. We observe its immediate effects from the sixth legislative term onwards. MEPs who used to accumulate offices had to make a career choice between the national and European political arenas. We observe that MEPs seem to have opted for a European career, as the percentage of accumulating MEPs has been declining (about 9% in the eighth legislative term) whilst European careerists have been growing. Nonetheless, this electoral reform did not entail the disappearance of all types of dual mandates (about 10% of all MEPs in the eighth term), because some Member States have maintained the possibility of accumulating regional political offices with an EP mandate.

The Accessibility of Seats in the EP: Career Maintenance Threatened by Increased Electoral Competition and Party Fragmentation

Accessibility describes the relative ease with which a certain position can be accessed (Borchert, 2011, p. 122). The transformations of party systems and electoral volatility are major factors that explain changes in MEPs' career orientation over time. Party fragmentation is unmistakably one of the most notorious evolutions in European democracies, albeit with important variations across countries (Casal Bértoa, 2021). Whilst a total of 57 national political parties were represented in the EP in 1979, this number increased to 168 in 2004 and reached 212 national political parties in 2019. Consequently, the electoral competition and, therefore, the accessibility of seats into the EP are now more challenging (especially for the ‘historical’ EPGs, which are the founding contributors of the European political class).

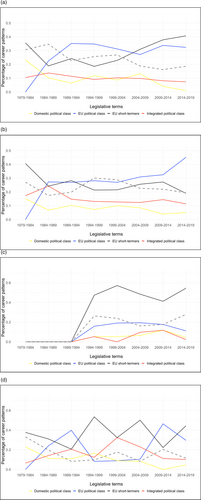

On the one hand, it became harder for long-term MEPs serving in the EP to remain in office amidst times of high electoral volatility. MEPs' seats were contested because of the electoral decline of traditional national party families such as the Socialists and Christian Democrats. Whilst the EPP and the Socialists held about 65% of all seats in the late 1990s, they subsequently lost their majority and hardly covered 45% of the seats after the 2019 European elections (Bolin et al., 2019). On the other hand, in a context of rapid transformations of party systems, the cohort of short-termers inflated (i.e., an increase of more than 10 points of percentage since the late 1990s to reach 36% in the eighth legislative term). One of the most striking evolutions is observed in the Socialist group (Figure 6a). Whilst this group had its highest shares of European-oriented MEPs during the 1980s–1990s period, electoral turmoil has eroded their capacity to maintain a strong core part of the European political class (European-oriented socialist MEPs declined from 35% at the third legislative term to 27% at the sixth legislative term). Even though they eventually stabilized around 30% during the 2010s, this constitutes some of their lowest proportions observed since 1989. Although part of this decline is due to the generational renewal amongst socialist ranks (long-term MEPs who were serving in the 1980s and 1990s have been replaced by a younger generation of MEPs), electoral volatility and the transformation of party systems have increased this trend. In this context of high electoral volatility and party fragmentation, the share of Socialist short-termer MEPs has constantly been on the rise since the mid-2000s, totalizing 41% in 2019. This reflects the electoral defeats of various social-democratic parties in Scandinavia as well as in Western and Southern Europe (see Benedetto et al., 2020). The EU enlargements and the relative success of social-democratic parties in Eastern Europe – albeit with some cross-country variation – could not inverse this tendency.

Notes: EU, European Union; MEPs, members of the European Parliament.

Until now, the decline of European-oriented MEPs amongst the Socialist group has been compensated by an increase amongst the EPP (see Figure 6b). Likewise, the Liberals and the Greens have also contributed to the maintenance of the European political class: European-oriented MEPs presented some of their highest proportions of European-oriented MEPs from the mid-2000s until the late 2010s (i.e., respectively, 30% and 40% of EU-oriented MEPs). However, this current maintenance of the European political class might be only temporary because of the incremental strengthening of Eurosceptic political groups. McElroy and Benoit (2012, p. 152) observed that ‘[a]ll of the member states now have some form of a Eurosceptic party competing in European elections. In the 2009 elections, far-right parties also won substantial support in some member states where they were not traditionally powerful’. Euroscepticism is now a ‘stable component of European politics’ (Brack, 2020, p. 1). And these Eurosceptic parties contributed substantially to the new cohort of short-termers (54% in 2019; see Figure 6c). Likewise, the EPP has been increasingly contested by the rise of the Conservatives group in the most recent elections, a group in which short-termers also tend to predominate (44% of their group in 2019; see Figure 6d).

Conclusion

The EP is meant to be the democratic pillar of the EU institutional architecture. Yet, the supranational institution can only fulfil its legitimacy roles when populated with a core of dedicated MEPs. That is to say, a European political class of MEPs ‘willing to exercise powers granted to their assembly’ (Scarrow, 1997, p. 253). By contrast, the EP's policy-making capacity is jeopardized when populated by MEPs using the EP as a ‘retirement home’ or a ‘training arena’ (Hix and Høyland, 2011, pp. 54–55). In this wake, various scholars have posited the development of a European political class following the empowerment of the EP over time. Yet, the literature is still missing a comprehensive empirical study, providing undeniable evidence of such evolution over time. This article seeks to fill this gap with two main research goals: (1) describing the evolution of career patterns of all 3634 MEPs from the 28 Member States who served during the 1979–2019 period and (2) explaining how the evolving structure of opportunity of the EP shaped the development of the European political class.

First, our empirical analysis unmistakably established that the EP attracted European careerists early since the second legislative term (1984 and onwards). Whilst a few national figures hit the headlines for moving to the EP as a mere ‘retirement home’, this kind of profile was mostly ‘the tree hiding the forest’. Our empirical results show that the development of a European political class is not a uniform trend, though: the professionalization of European careers is stronger in Western European countries as well as amongst the two most influential EPGs (i.e., Socialists and EPP).

Second, this article highlighted the effects of the multilevel institutional structure of opportunities. We posited that the increasing attractiveness of the EP would foster the development of a European political class over time. We argued that this trend could, however, be undermined because of a decreased availability of seats (i.e., stricter electoral regulations regarding dual mandates) combined with a reduced accessibility of seats in the EP (i.e., greater electoral competition and party fragmentation). Our results confirm that reduced accessibility of seats is one of the strongest drivers undermining the development of European-oriented MEPs. Party system transformations in the late 2000s and early 2010s resulted in the decline of European-oriented MEPs, especially amongst the Socialist group. So far, the consolidation of the European political class in the EPP – and to some extent amongst the Greens and the Liberals MEPs – has balanced the decline of the Socialists. However, the EPP has been increasingly challenged by the recent electoral successes of the Conservative and Eurosceptic groups. The 2024 European elections can only foster this trend, putting greater pressure on the current state of the European political class.

These recent transformations call for two prospective conclusions regarding the development of the EP as an institution. On the one hand, some might argue that this renewal in the European political class is a source of virtue for European democracy. The rise of the Conservative and Eurosceptic groups reflects the greater politicization of European elections in the post-Maastricht era of the ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks, 2009). Evolutions in the EP composition reflect changes in voters' behaviour, who signal their desire for alternative policies by sending new profiles of MEPs. After all, it has always been underlined that ‘new blood’ is vital for the functioning of our representative democracies (Atkinson and Docherty, 1992). On the other hand, some might argue that these evolutions are, on the contrary, potential vices for European democracy. During the late 2000s and 2010s, party transformations were not associated with greater – but lower – electoral participation at European elections. The average turnout has been structurally declining from 62% in 1979 to 42% in 2014, even though the 2019 and 2024 European elections are associated with a substantial increased turnout (51%). In other words, changes in the European political class do not always qualify as a process of democratization and maturation of the EU's political system, but sometimes a process of democratic decline in terms of electoral participation.

More critically, the entrance of new EPGs was not associated with a process of professionalization for their newly elected MEPs. On the opposite, this ‘new blood’ resulted in a neat increase in turnover in the EP: the newly elected MEPs from the Conservative and Eurosceptic groups are predominantly dominated by short-termers. As Squire (1992, p. 1026) observed, institutionalization is driven by insiders, whilst deinstitutionalization takes place because of outsiders. After all, ‘legislative institutions change along with the types of people attracted to serve in them’ (Matthews, 1984, p. 573). An EP populated by mere short-termers risks undermining the effective influence of the EP in EU policy-making processes (Daniel and Metzger, 2018).

Overall, we encourage scholars to further investigate two dimensions. First, the scholarship shall more systematically assess how the changes in career patterns impact the EP's policy-making capacity. The literature on MEPs' parliamentary behaviour has already established the decisive roles of several structural-level factors, such as EPGs, electoral rules or opposition status. Yet, further research should focus on individual-level factors and, in particular, the impact of career patterns upon legislative and parliamentary behaviour. For instance, Meserve et al. (2009) outlined that ‘nationally-oriented’ MEPs are less disciplined than ‘EU-oriented’ MEPs. Høyland et al. (2019) and van Geffen (2016) also showed the existence of a relationship between career ambition and parliamentary activities (see also Randour et al., 2022). This is of critical importance to understand how the EP can(not) fulfil its democratic role. Second, amongst the individual factors, we acknowledge that the gender dimension was beyond the scope of this article. Yet, it requires an agenda of research on its own – and not merely a control variable – considering that the EP is known for its ‘success story’ and ‘gender exceptionalism’. In sharp contrast with most national parliaments in Europe, the representation of female MEPs has grown from 15.2% (1979) to almost 40% in the latest European elections (European Parliament, 2019). In particular, the scholarship should systematically investigate how the so-called ‘second-order character’ of the EP undermines or boosts the profiles of certain men and women (Däubler et al., 2024; Dodeigne and Frech, 2024; Xydias, 2016) and how it impacts female and male MEPs' careers within the EP towards top positions (Kopsch and Dodeigne, 2022), as well as MEPs' career orientation on gendered parliamentary behaviour (Dodeigne et al., forthcoming).

References

- 1 When adapting our criteria, we observed hardly any changes for the domestic orientation (98% of the observations remain unchanged, hardly eight MEPs concerned), whilst we observed low variance for the European career orientation and short-termers labels (respectively, 88% and 90% of the MEPs' career patterns remained unchanged). In total, the stronger criteria used for the European orientation excluded merely 108 MEPs (785 instead of 893 MEPs), whilst we dropped 165 short-termers (1500 instead of 1665 MEPs).

- 2 These numbers are not mutually exclusive: some MEPs have accumulated domestic political experience prior to, during and after their EP mandate.

- 3 We shall also cautiously add that Daniel's (2015) results are based on multivariate regressions, whilst we simply present descriptive statistics in this contribution.

- 4 Our chief goals are to identify and explain the evolution of the EP composition as an institution – from a macro perspective. Although we cover 3634 individual MEP observations, our main interest is in the evolution of the EP composition over eight legislative terms (i.e., we thus have eight ‘macro’ observations). We seek to explain how changes in institutional and political factors (i.e., dual mandate regulation, institutional empowerment or party system transformations) are associated with key evolutions in the EP composition over time.

- 5 With the exception of Austrian and Italian MEPs.

- 6 The only notorious exception is the post-Lisbon period, which has coincided with a significant increase in European-oriented MEPs (from about a quarter before 2009 to about a third of MEPs afterwards). One of the reasons for this increase – but difficult to assess – may be the MEP single statute.