The European Union as a Target: When Do Democratic Backsliders Rhetorically Challenge the EU?

Abstract

Populist actors who conduct democratic backsliding incrementally eat away at institutional checks on power. Whilst they largely focus on domestic institutions, European Union (EU) member states have an international democratic institution to consider as well. In this article, we present and test a theory explaining changes in backslider rhetoric towards the EU. Whilst they often claim a position of Euroscepticism, their interactions with the EU are complicated. We argue that anti-democratic actors consider the public perception of the EU and the likelihood of enforcement and sanctions from the EU when deciding what type of rhetoric to use. Using speeches from Orbán in Hungary and Duda in Poland, we find that the effect of public opinion on speech sentiment varies between leaders. We also find evidence of position blurring in response to increases in EU threat levels.

Introduction

The rise of populism throughout Europe has provoked extensive scholarship about democratic backsliding and Euroscepticism. The populist actors who conduct democratic backsliding incrementally eat away at institutional checks, making it easier to maintain their power (Bermeo, 2016; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). Whilst they largely focus on domestic institutions, member states in the European Union (EU) have an international democratic institution to consider as well. Populists are often associated with Euroscepticism; however, there is variation in how populist leaders communicate with and about the EU.

The different stances on the EU amongst populists are especially true for populist backsliders, whose interactions with the EU are complicated. This is conveyed through a mixture of both negative and positive rhetoric (Winzen, 2022). At times, Eastern European leaders praise the EU for its dedication to preserving a European identity or strengthening the economy, and at other times, they reprimand the EU for overreach. Sometimes, these come within the same speech. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Polish President Andrzej Duda often face this dilemma in deciding how to talk about and to the EU. This leads us to question what type of rhetorical strategy populist backsliders use towards the EU and why.

Based on public opinion, institutions and democratization literature, we argue that anti-democratic actors consider public perception of the EU and the likelihood of monitoring and enforcement from the EU when deciding what type of rhetoric to use. We test hypotheses about public opinion and institutional threats on rhetoric. Results are mixed. Orbán's rhetoric follows changes in public opinion, with sentiment becoming more negative as public opinion of the EU becomes more positive. On the other hand, Duda's sentiment does not follow changes in public opinion, instead showing evidence of position blurring. We also find evidence of position blurring in response to increases in EU threat levels. This article contributes to the literature on strategic party competition as well as democratic backsliding, showing how backsliders use tone strategically when talking about the EU.

I Theory

We theorize that public opinion about the EU should affect the type of rhetoric backsliders use when talking about it. Because elites are concerned with electoral and office goals (Devinney and Hartwell, 2020; Strom, 1990), they should take voters' opinions into account. Whilst earlier literature views public opinion of the EU as a consequence of national circumstances and elite cues (Kritzinger, 2003), more recent studies show that public opinion about the EU affects elite actions. According to Hobolt and de Vries (2015), elites are aware of public opinion about the EU, with some forming parties based on the possibility of attracting voters who care about the EU. Williams and Spoon (2015) confirm the impact of public opinion, finding that shifts in public opinion about the EU result in shifts in parties' positions on the EU. This suggests that public opinion does affect the strategic decisions of elites and, thus, should matter for populists when they talk about the EU.

However, there is no consensus about the direction in which public opinion should affect elite rhetoric. Therefore, we test three competing hypotheses. In each, the backslider's interests are pulled in two directions. They have an incentive to admonish the EU for punishing backsliding because they want to continue backsliding and do not want to risk losing power. They also need to stay in the good graces of voters who like the EU. In each hypothesis, the backslider weighs these factors differently. We draw from Meguid's (2005) three strategies related to position taking: accommodative, adversarial and dismissive.

First, we hypothesize that as EU support amongst the public increases, the backslider's rhetoric will be more positive. This is an accommodative strategy, and taking this position benefits the backslider because adopting the position of the voters makes it more likely that the backslider will maintain power. Elites have shown themselves to be attentive to public opinion and to adopt positions accordingly (Hager and Hilbig, 2020). Spoon and Klüver (2014) and Klüver and Spoon (2016) provide evidence that parties are responsive to public opinion and are more likely to include issues on their platforms that the public cares about. Similarly, Bernardi et al. (2021) find that public opinion affects which issues legislators prioritize. We extend this theory to test whether public opinion similarly affects rhetoric.

Alternatively, we hypothesize that as EU support amongst the public increases, the backslider's rhetoric will be more negative. In this case, the backslider decides it is more advantageous to convince voters to dislike the EU than it is to adopt their position. This is akin to an adversarial position. Research shows that elites have an impact on public opinion via framing and agenda setting. Especially in polarized settings, voters look towards partisan elites to form opinions (Slothuus, 2010). Voters respond quickly to these elite frames, updating their own positions to match those of party leaders (Slothuus and Bisgaard, 2021). Therefore, we might expect backsliders to use negative rhetoric to convince voters to turn against the EU.

Finally, we hypothesize that as EU support increases, the backsliders will blur their position. Drawing from Meguid's (2005) dismissive strategy, we test whether public opinion leads to avoidance of the issue altogether. Because we know that backsliders continue to talk about the EU, avoidance comes in the form of position blurring. Position blurring is when a politician ‘present(s) seemingly contradictory arguments on a given issue’ (Han, 2022), leading to uncertainty about their actual position. They want to avoid losing support by taking the adversarial position, whilst also avoiding accommodating a positive EU position because it does not serve their goals. Blurring can also be helpful because it forces voters to evaluate elites based on other issues. If the elite is at odds with the stance of voters, they risk losing votes, but if nobody knows the elite's position, they have to rely on other issue positions (Han, 2022; Rovny, 2012). Research shows that some populists have taken this approach on economic and social issues (Zulianello and Larsen, 2023), and in this article, we test whether this is also the case for backsliders and the EU.

Institutional Threat

The second factor we argue affects rhetoric towards the EU is backsliders' perceptions about institutional threats. Most incidents of democratic backsliding are conducted by actors who incrementally weaken democratic institutions and concentrate power in their own hands (Bermeo, 2016). Because of limited time and the risk of creating backlash, they cannot target every institution all the time. Therefore, these actors make strategic decisions.

As we mentioned, backsliders have electoral goals and will act strategically to achieve them (Strom, 1990), and there is evidence that they have policy goals as well. Devinney and Hartwell (2020) argue that there is no monolithic agenda for all populists but that each populist party has its own policy goals. Others have shown that populists actively work to achieve these goals (Caiani and Graziano, 2022; Rinaldi and Bekker, 2020). Given this, we expect that populists should pay attention to institutions that can, and are likely to, block their policy goals. Based on the literature about checks and balances, we hypothesize that changes in the threat level of an institution, made up of both the ability and willingness to use its powers over the executive, should affect rhetoric towards the EU. An institution becomes a higher threat when new ways to warn backsliders are introduced, and when actors in the institution become more willing to use them. In domestic contexts, democratic institutions often have powers given to them through a constitution or legislation but are more likely to use those powers when actors within the institution are not allies of the backslider (Call, 2024).

We argue that this translates into the international sphere as well. The EU has continuously touted its commitment to democracy since the signing of the Single European Act (SEA, 1986), when member states were ‘determined to work together to promote democracy on the basis of … fundamental rights’ (p. 5). States including Hungary and Poland achieved the level of democracy necessary to be made members of the EU in the 2000s, including the ‘stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy’ (European Council in Copenhagen, 1993). For several years following accession, these states continued their democratic trajectory. However, after Orbán became Prime Minister of Hungary in 2010 and Duda became President of Poland in 2015, these states turned away from democracy.

This change has sparked a debate in the EU and within academia about the ability and effectiveness of current enforcement tools to handle rule of law violations. In his 2012 State of the Union speech, EU Commission President José Manuel Barroso (2012) referred to the democratic erosion in Hungary, stating that ‘these situations also revealed limits of our institutional arrangements. We need a better developed set of instruments’. Scholars including Müller (2015) and Theuns (2022) agree, arguing that Article 7 and infringements are not up to the task of defending democracy. Müller (2015) even suggests the creation of an entirely new EU enforcement institution. However, there are also scholars who argue just the opposite – that the EU already has effective tools; it just needs to use them (De Búrca, 2022; Sadurski, 2022). For example, Scheppele et al. (2020) point out that EU law already has sufficient sanctioning power. Bugarič (2016) concurs and asserts that the real problem with existing mechanisms is the lack of political will to use them.

Although the EU was slow to adjust to the increasing prominence of backsliders within its ranks, especially their delayed response to Hungary's illiberal turn, it did recognize that backsliding was happening. They also recognized the shortcomings of its monitoring and enforcement mechanisms and created new ones. We argue that these changes increased the EU's threat level and, in turn, impacted populist rhetoric. Once again, we use the position-taking strategies popularized by Meguid (2005) to formulate hypotheses.

First, we test the hypothesis that when the threat level of the EU increases, backsliders will use more negative rhetoric. In this case, the backsliders respond defensively to the hinderance of their goals, which Meguid (2005) identifies as an adversarial strategy. Using negative rhetoric will potentially influence public perception of the EU, making the backslider's voter base less supportive of it. If the populist leader can successfully decrease public support for the EU, their own leverage will increase because the EU may be hesitant to risk further alienation by punishing the government.

An alternative hypothesis is that when the threat level of the EU increases, backsliders will use more positive rhetoric. In this case, we would see the backslider use positive rhetoric to assuage the EU and make it less likely to use monitoring mechanisms. This is similar to accommodation (Meguid, 2005; Spoon and Klüver, 2020). Backsliders could potentially use this strategy, responding positively to the concerns of the EU. The positive rhetoric may signal to the EU that the backslider is an ally, thereby making sanctions less likely, while also signaling to voters that the backslider has a positive relationship with the EU.

Although Meguid (2005) does identify a third strategy, dismissive, this is evidently not the case here. Both backsliders mention the EU consistently in their statements, and the EU is too salient to ignore. Instead, if a politician wishes to avoid taking a position without ignoring the issue altogether, they may blur their position. According to Rovny (2012), radical right parties may try to ‘project vague, contradictory or ambiguous positions’ with the goal ‘to either attract broader support, or at least not deter voters on these issues’. We extend this theory to backsliders, testing the hypothesis that when the threat level of the EU increases, backsliders will blur their position.

II Data and Methods

The dependent variable of interest is backslider rhetoric towards the EU, or more specifically, the type of rhetoric used. Following suggestions from Seawright and Gerring (2008), we select the two most extreme examples of backsliding states within the EU: Hungary and Poland. According to Varieties of Democracy, the mean liberal democracy score in the EU dropped from 0.78 in 2010 to 0.73 in 2020, a 6.4% decrease. Hungary went from a score of 0.77 to 0.36, a startling 53% decline, and Poland changed from 0.84 to 0.46, a drop of 45%. We note that, as extreme cases, Hungary and Poland are not necessarily representative of all EU countries. However, we also argue that Hungary and Poland may in fact become influential cases – other leaders have not been shy about following Orbán's ‘authoritarian playbook’, including Slovenia's Janša (Delić, 2020). In addition, far-right populists continue to win elections across Europe. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders and his populist party, the Party for Freedom (PVV), just won the most parliamentary seats in November 2023, and he is well known for his anti-EU sentiment. There are also several countries with discouraging declines in democracy, including Slovenia, which had a 19% decline in liberal democracy during 2010–2020, Greece with a 14% drop, and the Czech Republic with a decline of 11%. Rhetoric in Hungary and Poland may therefore be a preview of more widespread rhetoric in the future. Furthermore, because these cases are recent, there are many speeches available in English on the official websites of their respective governments (please see Appendix S1 for a more detailed explanation of speech selection and for the list of quoted speeches).

Following the literature on backsliding and populism, we select Orbán and Duda as our actors of interest. Both are identified as drivers of backsliding in their respective countries, and both had their own power increase at the expense of democratic actors and institutions. Whilst there is significant scholarship suggesting that backsliding was initiated by Jarosław Kaczyński, the agenda-setting leader of the Law and Justice Party (PiS) since 2003, the availability of his speeches is limited. There are some English translations of Kaczyński's speeches available on the PiS website, but they are either partial statements, or are interspersed with additional analysis from the party. This makes it difficult to systematically collect complete statements, which are necessary to capture the speaker's sentiment. Some scholars have directly translated videos of Kaczyński's speeches, or collected his speeches on a particular topic, but for the purposes of this analysis, those corpuses are not expansive enough, or do not provide enough material relevant to the EU. This leaves Duda's speeches as the best test for our theory (Alekseev, 2022; Paluchowski and Podemski, 2019). 1 Further, because Duda and Kaczynski are allies (Duda was hand selected by Kaczynski to be Poland's president), we think it is plausible that Duda's speeches reflect shared positions and strategies. Duda's statements are all available through the official website of the President of Poland.

Through keyword searches, 2 we first identified statements referring to the EU. We then conducted sentiment analysis of speeches primarily about the EU versus non-EU speeches. For each, we identify the proportion of positive and negative contents using the Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (Young and Soroka, 2012). 3 A descriptive table can be found in Table S2.

Independent Variables

We take a qualitative approach to determining when institutional threats change. Based on our theory of institutional threat, we expect that when a new monitoring mechanism is introduced or when the EU becomes more willing to use mechanisms, sentiment should change.

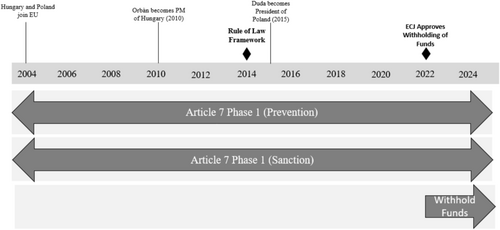

Through the literature, we find the following mechanisms: Article 7, the Rule of Law Framework and the strategic withholding of funds, illustrated in Figure 1. We argue that even with their inherent weaknesses, new mechanisms nonetheless provide the EU with additional opportunities to prevent backsliders from achieving their goals. Due to this increased threat, when new monitoring mechanisms are introduced, we expect the rhetoric to change. We also expect rhetoric to change when the EU shows its willingness to use these mechanisms; some mechanisms were introduced but not implemented until several years later. For example, although the Rule of Law Framework was introduced in 2014, it was not used until 2016. When the EU becomes more willing to use the mechanism, as signalled by its implementation, the threat level increases, which we expect will change the sentiment of backsliders' rhetoric towards the EU.

Notes: ECJ, European Court of Justice; EU, European Union; PM, Prime Minister.

Article 7 and the Rule of Law Framework

The first tool is Article 7 of the Treaty on the EU (TEU), to be used if there is a ‘clear risk of serious breach of EU values’. Article 7 can theoretically threaten backsliders, but in practice, high thresholds make it impossible for member states to be held fully accountable (Pech and Scheppele, 2017). Furthermore, as both Hungary and Poland have seen substantial declines in liberal democracy, they will not vote to suspend the other (De Búrca, 2022). Orbán (2017) made this explicit in a radio interview, saying, ‘when someone attacks Poland – as Brussels is doing now – they attack the whole of Central Europe. So we must stand by the Poles’. Under these conditions, the sanctioning arm of Article 7 is effectively hamstrung.

Historically, the EU has been reluctant to use Article 7, but this seems to be changing. By the end of Orbán's 2010–2014 term, it was becoming very clear that rule of law violations in Hungary would likely continue if no action was taken. The Commission itself admitted that ‘the EU had to find ad hoc solutions since current EU mechanisms and procedures have not always been appropriate in ensuring an effective and timely response to threats to the rule of law’ (Rule of Law Framework). The Commission's solution was to introduce the Rule of Law Framework in 2014, ostensibly to prevent incidents from reaching Article 7 levels (European Commission, 2014). The Framework, however, has been criticized in academic literature as a way for the Commission to further avoid using Article 7 and its associated sanctions and thus continue not punishing backsliding member states (Closa, 2021). However, not all scholars agree. Kochenov and Pech (2016) argue that despite its weaknesses, the Framework was still ‘a modest step in the right direction’ (p. 1066) and ‘showed that the Commission finally understood the serious, if not existential, threat posed by the solidification of authoritarian regimes within the EU’ (p. 1066). Prete (2017) points out that the Framework ‘is intended to address future threats to the rule of law in Member States which are of a systemic nature, before the conditions of activating the mechanisms provide for in Article 7 TEU are met’ (p. 223) and, as such, ‘is probably a useful addition to the arsenal which the Commission already has at its disposal’ (p. 225).

The EU signalled its willingness to use these tools first in January 2016, when the Commission triggered the Rule of Law Framework against Poland. It was the first (and currently only) use of this tool. 4 In another first, the European Commission triggered Article 7 in December 2017, using it to warn Poland about possible threats to judicial independence. This was a significant event because Article 7, even the preventative stage, had never been used. Then, in September 2018, the European Parliament triggered the warning phase of Article 7 against Hungary. The use of both the Framework and Article 7 signalled that the EU was more willing to use these tools than before.

We expect backslider rhetoric to change when the Rule of Law Framework is introduced because it indicates that the Commission is aware of growing threats and is attempting to redress them. We also expect backslider rhetoric to change when the Commission uses the Framework and Article 7 because it signals a willingness to use these checks, even if the available tools are imperfect. Although the EU's uses of the Framework and Article 7 may apply to one specific backsliding member state, we argue that it should affect the actions of other backsliding member states because it signals an increased willingness to use these mechanisms, or potentially others, in the near future. Therefore, the introduction of the Framework and its use in 2016 against Poland, the use of Article 7 on Poland in 2017 and the use of Article 7 on Hungary in 2018 are events that increase the threat level of the EU to both Poland and Hungary. 5

Withholding of Funds

More recently, the Commission developed a new way to warn backsliders, the Rule of Law Conditionality mechanism, which was introduced in late 2018, approved by the European Council in December 2020 and came into force in January 2021. This mechanism allows the Commission and Council to suspend EU funds for member states if rule of law violations threaten the budget. In 2021 and 2022, the Commission used this mechanism and recommended that €7.5 billion in EU funds be withheld from Hungary and Poland due to concerns about corruption (Tidey, 2022).

The Commission has since used this mechanism in direct reference to backsliding, withholding COVID relief funds from Hungary until issues of judicial independence were addressed (Strupczewski, 2022). This strategy has already sparked action in Hungary, with the Commission demanding, and Hungary agreeing to a deal in which Hungary meets milestones in combatting corruption and empowering democratic institutions before funds are released (Strupczewski, 2022). From this, we know that the EU now has a functional check on backsliders. Also, as this check can be used without the input of Hungary or Poland, the veto power they have used in the past to protect each other is no longer an option. Effectively, this lowers the amount of political will and power needed to punish backsliders.

Given that this new mechanism provides a check on backsliders and is likely to be used, the EU has become a higher threat institution towards backsliders. Through this analysis, we have argued and provided evidence that the introduction of the Rule of Law Framework, the use of Article 7 and the withholding of funds increased the threat level of the institution. We expect, therefore, that backsliders' negative rhetoric will increase in 2014, when the Rule of Law Framework was implemented, and in 2022, when the Commission withheld EU funds from backsliders using the Rule of Law Conditionality mechanism.

Public Opinion

The other variable we theorize should affect the rhetoric of backsliders is public EU support. We operationalize this using a Eurobarometer survey question that asks respondents about how they see the EU. Variables were recoded so that higher values reflect higher levels of EU support. It ranges from 1 (a very negative image) to 5 (a very positive image). We use the yearly weighted average responses from Hungary and Poland as our measure of public EU support.

However, research suggests that public EU support is not just about evaluating the EU directly but involves a comparison of attitudes about the perceived benefits of their home state remaining in the EU with the benefits of being in an alternative state outside the EU (De Vries, 2018). This means that citizen attitudes about the EU are closely linked to perceptions of how well things are going in the home state, or, in other words, how well their national governments are doing. When citizens of a member state approve of their national government, they are more likely to disapprove of the EU, in part because their interests are already being served, rendering the EU superfluous. On the other hand, when citizens disapprove of their national government, the EU is sometimes seen as a safety net that will ensure their needs are met regardless of how poorly their national government performs. Because public opinion of the EU and of national governments is intertwined in this way, we include the opinion of national governments in our model.

That means that opinion about national governments may be an important confounding factor – domestic government support may be what is affecting leader rhetoric, not public support for the EU. To account for this benchmarking effect, we also examine trust in national governments, using a second question from the Eurobarometer. This variable asks respondents about their trust in national governments and was recoded with values ranging between 1 and 3. Answers coded as 1 indicate that the respondent tends not to trust the national government, 2 if they do not know or are neutral and 3 if they tend to trust the national government. We again use the weighted mean response from each respective country.

III Results

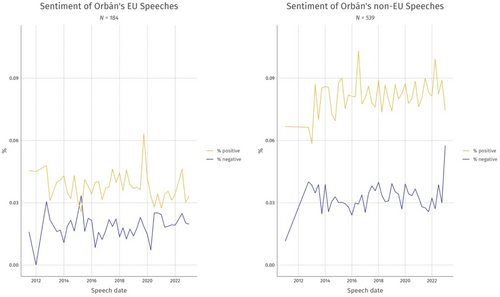

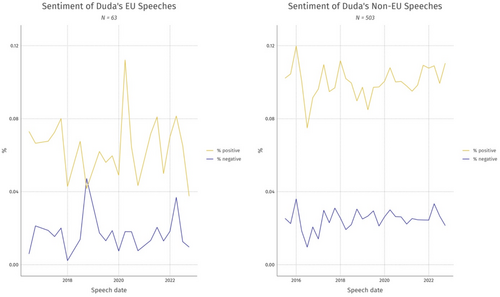

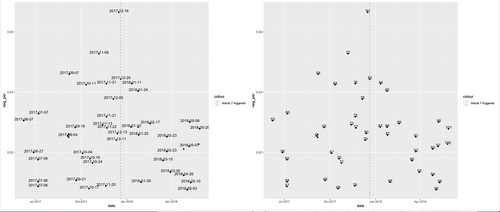

An overview of sentiment analysis scores can be found in Figures 2 and 3, which are further summarized in Table S1.

These figures plot the average quarterly sentiments of speeches about the EU, compared with non-EU speeches from Orbán and Duda. As the plots show, statement sentiment varies over time and across types of speech, sometimes dramatically.

Figure 3 shows the mean sentiment scores of Orbán's EU speeches compared with non-EU speeches. The average positive sentiment is clearly higher in his non-EU statements, whilst the mean negative speech is higher in EU speeches. This suggests that Orbán's speech about the EU is different from his other speeches and that it is more negative. Additionally, the difference between positive and negative communications about the EU is lower than in non-EU speeches (or all speeches), even crossing, providing evidence that Orbán uses blurring.

Sentiment plots of Duda's statements are in Figure 3. The left-hand panel shows sentiment scores for his EU speeches, whilst the right-hand panel shows scores for non-EU speeches. Two things are apparent. First, the average sentiment of Duda's non-EU speeches is more positive than the sentiment in his EU speeches; in other words, when he talks about the EU, he uses less positive speech and more negative speech.

Second, EU speeches are more variable than non-EU speeches. There are a few minor spikes between 2015 and 2016 for non-EU statements, but both the range and the rate of variable statements are higher when Duda talks about the EU. In the fourth quarter of 2017, negative speech jumped dramatically, with a corresponding dip in positive speech. The EU Commission triggered Article 7 against Poland in late 2017 and may therefore be the driver behind the spike in negative speech. The first quarter of 2019 saw a large spike in positive speech, followed by a rapid slip in the second quarter. In April 2019, the EU Commission launched an infringement procedure against Poland, arguing that new laws undermined judicial independence. Statements may have become more negative in response. 6 These events, as well as the variation in sentiment scores and their volatility, provide some evidence that Duda's EU statements are different than his average statements and that Duda responds to EU action.

Public Opinion

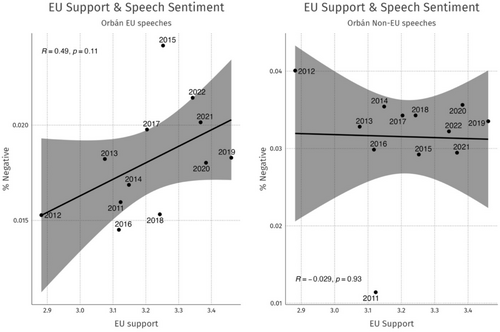

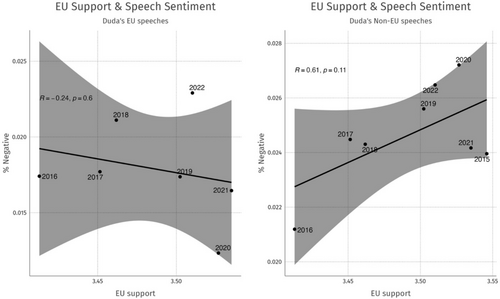

Figure 4 illustrates the slight positive correlation between public EU support and negative speech in Orbán's EU speeches; however, the relationship is not quite statistically significant. The direction of the relationship does provide some evidence that when public support for the EU increases in Hungary, the tone of Orbán's EU speeches is more negative. This is different from the effect of public support on Orbán's non-EU speeches – these have a slight negative correlation, but again, it is not statistically significant. We note, however, that this is what we would expect. We would not expect public EU support to have an effect on Orbán's non-EU speech.

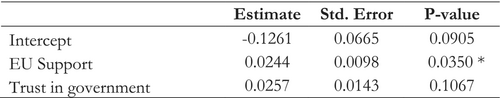

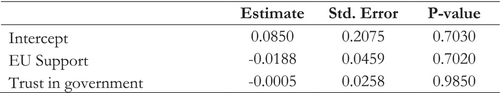

Figure 5 shows the effects of public EU support and feelings of trust towards the government on negative speech sentiment for Orbán's EU speeches using linear regression. Controlling for government trust does somewhat reduce the size of EU support's effect, but it becomes statistically significant. This provides evidence supporting our adversarial hypothesis for Orbán. In other words, when public support for the EU increases, Orbán's negative speech increases. It also suggests, at least in this case, that an important potential confounder is also not driving the results – opinions about the national government are not associated with negative rhetoric, whilst public EU support is.

Statements made by President Duda do not follow the same pattern. Instead, his statements show evidence of blurring, as shown in Figure 6. As public EU support increased, Duda's EU speech became more negative; however, it is not statistically significant. Contrary to expectations, the percentage of Duda's non-EU speech with negative sentiment actually increases slightly as public support for the EU increases. These results are also not statistically significant but are in the expected direction for the blurring hypothesis.

The blurring hypothesis is further supported by Figure 7 and the lack of a statistically significant relationship between negative rhetoric and public EU support, controlling for trust in national government. Even after accounting for national government trust, the results remain null. The effect of public support on Duda's negative EU speech does not change. 7 This stands in contrast with Orbán, who we argue takes an adversarial position, and suggests that Duda is more likely to blur his speech.

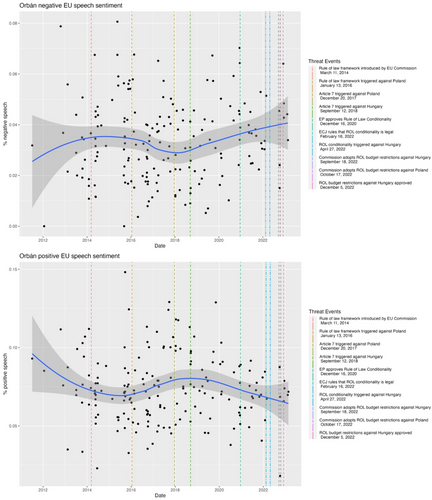

Institutional Threat

Figure 8 shows the negative and positive sentiment scores for Orbán's EU statements over time. Each dot denotes one statement at one point in time. The blue horizontal line is the lowess mean negative (positive) sentiment score, and it suggests that negative rhetoric has generally increased (positively decreased). The vertical lines each represent a potential threat to the Hungarian government from the EU. For example, the first red line marks the 2014 introduction of the Rule of Law Framework. Figure 8 shows that, in general, negative rhetoric increased over time and positive rhetoric decreased. However, when each threat-increasing event is investigated individually, there is not an immediate, significant change in sentiment.

Rather, we see a wide range of sentiments both in the months before threat-increasing events and in the months after. For example, in 2022, before the budget restriction on Hungary was approved, Orbán's statements showed a mix of positive and negative sentiments. After the approval (18 September 2022), Orbán made a series of three statements about the EU on 28 September, 7 October and 9 October that similarly varied in sentiment. The first two had moderate levels of negative sentiment, whilst the third had much less negative sentiment. Two months later, negative sentiment increased again. This indicates that Orbán was blurring his position both before and after these threat-increasing events. It is important to note that these statements were relatively short and did not mention the approval of the budget restriction, which could provide further evidence that Orbán wanted to make his position less clear. We see similar patterns surrounding other threat-increasing events, including the triggering of Article 7 in September of 2018 and the triggering of the Rule of Law Conditionality in April 2022.

There are also several similarities between the trends in sentiment for Orbán and Duda. For Duda, like Orbán, negative sentiment increased over time (see Figure S1). Consistent again between the two leaders is that when we focus on specific threat-increasing events, sentiment is similarly blurred both before and especially after the events. As seen in Figure 9, there was a wide spread of negative sentiment both before and after Article 7 was triggered against Poland. Notably, most of the statements made in the 3 months after Article 7 was triggered do not mention Article 7, and in fact, there were no statements made primarily about the EU during that time.

IV Orbán's and Duda's Blurring Strategies

We have shown, thus far, that there is evidence that backsliders use a blurring strategy when speaking about the EU. This becomes clearer when we look at the statements Orbán made directly before and after the introduction of new ways to punish backsliders in the EU. For example, we observe that in multiple statements given in the 2 weeks leading up to the introduction of the Rule of Law Framework on 11 March 2014, Orbán uses low levels of negative sentiment, but in the statements given after the introduction, sentiment varies widely.

In a 4 March 2014 statement, Orbán addressed the crisis in Ukraine, about which the Hungarian government's position diverges from that of the EU. Even in the context of this crisis, Orbán (2014a) used relatively positive sentiment whilst talking about the EU's position and did not strongly criticize the EU. He urged other Hungarian politicians to be careful of how they speak about the crisis and to avoid ‘irresponsible comments’ and ‘irresponsible behaviour’. Orbán (2014b) continued this positive sentiment in a speech on 10 March 2014 in which he discussed the good work his government has done in distributing EU funds. These statements show that Orbán was using positive sentiment before the introduction of the Rule of Law Framework.

Following the introduction of the Framework, Orbán's speeches became less uniformly positive and began to vary in sentiment. On 14 March 2014, Orbán was interviewed for a television programme in which he spoke about the EU using negative sentiment. In this interview, he characterizes Hungary's relationship with Brussels as a ‘battle’ and says he has ‘defended the country from the Brussels bureaucrats’ (Orbán, 2014c). In a speech given on 18 March 2014, Orbán (2014d) used mixed sentiment, both praising individual countries within the EU and labelling ‘bureaucrats in Brussels’ as an obstacle to Hungary achieving its goals. These statements make it clear that there was a blurring of sentiment following the introduction of the Rule of Law Framework. Whilst in the weeks before the introduction of the framework, Orbán used mostly positive sentiment, in the weeks after, he used more mixed sentiment when talking about the EU.

Duda also blurs his rhetoric, though his blurring is constant before and after threat events, as seen through the statements he gave in the weeks leading up to and following the European Parliament's approval of the Rule of Law Conditionality on 16 December 2020. In statements leading up to the approval, Duda expressed mixed sentiments towards the EU. Whilst he touted the ‘unique benefits of membership in the European Union’ (Duda, 2020b), advocated for a strengthening of the EU (Duda, 2020a) and praised the EU for its economic efforts (Duda, 2020c), he also warned the EU against playing favourites amongst member states and to only act within the confines of the treaties (Duda, 2020c). Even though this is not as negative as Orbán's sentiment, it still shows that Duda was not always presenting the EU in a positive light. This mixed sentiment is reflected in Figure S2, which shows that the statements made in the weeks before the approval of conditionality varied in positive and negative sentiments.

This strategy was used after the approval of conditionality, as well, with Duda blurring his position in statements given in the second half of December 2020. In a statement made on 24 December, he expressed support for Moldova joining the EU (Duda, 2020d), and on 31 December, he mentioned the EU's role in fighting the coronavirus, but quickly reshaped the message to focus on the successes of Poland in getting and administering the vaccine rather than on how the EU led the effort (Duda, 2020e). Duda's sentiment was not significantly different in these statements than in earlier statements, and by mixing in EU policy with his own policy, he further blurs what his own position is relative to the EU. Altogether, this provides further evidence that backsliders primarily blur their positions with regard to the EU.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, we tested two sets of hypotheses about the rhetoric used by backsliders when speaking about the EU. The first set of hypotheses focused on whether and how public opinion affects the type of rhetoric used. We found that as public opinion of the EU increased, Orbán's sentiment became significantly more negative. This supports the hypothesis that as the public's EU support increases, the backslider's rhetoric will be more negative. Duda's sentiment, however, became increasingly blurred as public support for the EU increased, lending itself more to the blurring hypothesis.

This could be due to different political circumstances. Orbán might behave differently than Duda due to the size of the majority support. In Hungary, Orbán was elected in 2010 with a 2/3 majority for his party, Fidesz, in Parliament, and he was re-elected with just over 60% of the votes in 2014. He was re-elected again in 2018 and 2022 with each governing coalition receiving a 2/3 majority of votes. This is important in Hungary because 2/3 is the majority needed to change the Constitution (which the governing coalition has often done). Even though the public generally has a positive view of the EU, Orbán has enough power to do what he wants, including challenging the EU through increasingly negative speech. In contrast, Duda won just over 50% in 2015 and 2019, and his party held just over 50% of the seats in the Sejm (IPU Parline, 2015, 2019). This is not as clear of a mandate, meaning Duda was more vulnerable to changes in public opinion. Therefore, he blurred his position to prevent losing support. Overall, this indicates that public opinion does affect rhetoric, but is also impacted by the political support the backslider has at home.

We found evidence of blurring when testing the institutional threat hypotheses as well. There was no clear change in sentiment for either Duda or Orbán after threat-increasing events, but there was consistent blurring. This lends support to work by parties and competition scholars who find that politicians, and especially populist parties, blur their positions when they risk losing voters (Elias et al., 2015; Han, 2020; Nasr, 2022; Rovny, 2012; Rovny and Polk, 2020). Not only did they blur tone within statements, they also blurred tone across statements, sometimes lauding the EU's efforts one day and scolding them the next.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our data. All statements analysed came directly from the official websites of each member state. This means that there is a chance that more controversial statements were left out. This too could be viewed as tone blurring, though retroactively. The selection of which statements to archive online, therefore, could be further evidence that backsliders want their position about the EU to remain unclear. Future studies should further clarify if this is the case. We also note that infringement procedures, which are an important and potentially effective tool against backsliding, are not included in the present analysis of institutional threats. Future studies will need to deal with the challenges of identifying both the obvious rule of law infringements and the less obvious de facto ones, in addition to questions about their effectiveness and the circumstances of their use (or non-use).

This article contributes to both the literature on strategic party competition and democratic backsliding, showing how backsliders use tone strategically when talking about the EU. Whilst the literature largely focuses on populist and radical right parties, we apply our theoretical framework to backsliders, a group whose rhetoric and actions have an impact on the quality and level of democracy. We find that they, too, blur their positions. We also find that public opinion affects the tone of rhetoric used by backsliders, contributing to the literature on responsiveness and elite cues. These backsliders use their rhetoric strategically, and this article brings us closer to understanding under what circumstances we can expect rhetoric towards the EU to change.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FVC is supported by Wellcome (300088/Z/23/Z).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Eurobarometer data are available through the European Union's website (https://europa.eu/eurobarometer). For access to the corpus of statements and code used for analysis, email Kari Waters at [email protected].

References

- 1 We do, however, provide a couple of examples of Kaczyński's speeches being similar to Duda's later in the text.

- 2 Keywords: Europ*, EU, Brussels, Common, Market.

- 3 For more information about the Lexicoder dictionary, please see Appendix S1.

- 4 Arguably, the Commission should have used the Framework against Hungary in 2015, as suggested by Kochenov and Pech (2016). The Commission, however, stated that the scope conditions were not met in Hungary. A more pessimistic explanation is that Orbán's consolidation of power was complete, and there was nothing the Rule of Law Framework could do (Kochenov and Pech 2016).

- 5 Closa (2021) argues that the institutional logics driving the use of Article 7 against Hungary (by the Parliament) and Poland (by the Commission) were different. Nonetheless, the downstream effects of launching Article 7 are largely the same. Both Hungary and Poland were warned about democratic backsliding in general (and judicial independence in particular; please see Table S1), and the EU was demanding they reverse course. The fact that there are two EU institutions willing and able to launch Article 7 makes its use more likely and, therefore, more threatening.

- 6 In an April 2019 speech, Kaczyński shows the same ambivalence as Duda. Kaczyński claims that ‘We know what needs to be done to make Poland stronger’. This involves ‘being a member of the European Union’ and ‘simultaneously preserv[ing] [Poland's] sovereignty, that the decisions would not be taken for it, that it would be able to settle its matters in a right way, in a way that is supported by the majority of society, that we could simply do everything that serves Poland well. And we, here in Poland, know best what serves well our people, our homeland’ (speech from 4 April 2019, transcribed and translated by Alekseev 2021).

- 7 Blurring also shows up in Kaczyński's speeches in 2019. In a 30 April 2019 speech, he says, ‘if you want that this wave that has already been harming Western Europe and starts harming Poland to be held back, to be fought back in the European Union, in the institutions of the European Union, then it is truly important for the formation that would face it to be able to face it, because it has got a lot of experience in the European Parliament, because it has [gained] indeed a great love of MEPs. This formation is the Law and Justice’ (speech from 30 April 2019, transcribed and translated by Alekseev 2021). This negative view contrasts with parts of a speech on 5 April 2019 where he says that ‘being a member of the European Union – today this is a requirement of Polish patriotism’ (speech from 5 April 2019, transcribed and translated by Alekseev 2021).