Insights Towards Trauma-Informed Nursing Supervision: An Integrative Literature Review and Thematic Analysis

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach to healthcare practice that recognises the pervasiveness of trauma, and the deep and life-shaping impact this has on a person. The literature recognises the negative consequences of trauma both to the people who experience it, and the nurses who provide care for them. Professional supervision is an integral element of workforce wellbeing and practice development, and a largely unexplored avenue of support for those who deliver TIC. Strategies for delivery of TIC were clearly articulated in the background literature, however how professional supervision can support nurses who provide this was less obvious. The research aim was to explore the literature related to trauma-informed supervision in nursing to answer the question ‘what skills and strategies can a supervisor use to support nurses who provide TIC in adult populations?’. An integrative review method was used and identified fifteen published articles for inclusion. These were then analysed using a reflexive thematic analysis. Literature all came from the allied health field, due to paucity of literature related to nursing. Analysis revealed three themes that were developed into an emotion–cognition–action sequence; create a safe supervisory relationship; facilitate TIC learning; and build resilience. Discussion noted the intersection of review findings with the Supervision Alliance Model and TIC framework, and where other skills may be integrated to inform a trauma-informed supervisor.

1 Introduction

Across healthcare services globally there is a growing attention on the trauma experiences of people, and the negative developmental and health consequences this may produce across their lifespan (Dowdell and Speck 2022; Sansbury, Graves, and Scott 2015). Many authors note the incredibly high prevalence of trauma amongst people accessing mental health and addiction services, and the negative consequences of this to both the people who experience it, and the clinicians who provide care for them (Goddard et al. 2021; Isobel 2021; Muskett 2014; Portman-Thompson 2020; Sansbury, Graves, and Scott 2015).

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is an approach to the delivery of health care that recognises the prevalence and pervasiveness of trauma and provides care in such a way as to enhance engagement and avoid re-traumatisation (Dowdell and Speck 2022; Isobel 2021; Portman-Thompson 2020; Sansbury, Graves, and Scott 2015; Wilson, Hutchinson, and Hurley 2017). Research and development of TIC began over two decades ago and was initially presented by Harris and Fallot (2001). An internationally established group and leader in TIC named Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) further developed the concept with a framework for provision of trauma-informed care.

Since the publication of TIC frameworks, many authors have undertaken research to identify the level and impact of TIC implementation in nursing practice (Fleishman, Kamsky, and Sundborg 2019; Molloy et al. 2020; Muskett 2014; Nizum et al. 2020; Portman-Thompson 2020; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014; Sweeney and Taggart 2018; Wilson et al. 2021; Young et al. 2019), and to gain understanding of the challenges nurses face (Molloy et al. 2020; Muskett 2014). Isobel and Thomas (2022) described that nurses across general, and mental health and addiction care settings, are in a trusted and privileged position to hear people's stories and observe their suffering, distress and pain. By bearing witness to the traumatic experiences of a person's past, and through the process of being compassionate and empathic in a therapeutic relationship, nurses expose themselves to the risk of vicarious trauma. Both Isobel and Thomas (2022) and Sansbury, Graves, and Scott (2015) explained that clinicians must actively safeguard themselves from the intensity of working with people who report traumatic experiences; describing the pervasive and significant effects of TIC as a workplace hazard with both personal and professional consequences.

An already established well-being and professional development practice within mental health and addiction nursing is professional supervision (Davys et al. 2017; MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie 2016; Te Pou 2021). Professional supervision provides protected time to use a strengths-based approach to review and reflect on practice with an experienced practitioner (Martin et al. 2021). There is an assumption that this practice will benefit both the knowledge and expertise of the supervisee, and increase positive outcomes for the people they work with (Martin et al. 2021; Simpson-Southward, Waller, and Hardy 2017; Te Pou 2021).

The prioritisation of regular professional supervision for staff utilising a TIC approach has been stated by several authors (Isobel 2021; Isobel and Thomas 2022; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014; Wilson, Hutchinson, and Hurley 2017), the goal of which is to facilitate reflective practice and support the emotional wellbeing of clinicians. To achieve these goals the TIC literature is consistent in acknowledging that an increase in resourcing and access to professional supervision is imperative (Isobel 2021; Isobel and Thomas 2022; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014; Wilson, Hutchinson, and Hurley 2017). However, the strategies that inform trauma-informed supervision practices were less clear and are the focus of this integrative review.

2 Aim

The aim of this research was to explore the scholarly literature related to trauma informed care in nursing supervision to answer the question ‘what skills and strategies can a supervisor use to support nurses who provide TIC in adult populations?’

3 Method

The integrative review process described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) was the method chosen for this literature review. This method is valued in nursing research as a tool to build nursing science that may become directly applicable towards informing future nursing research, practice and policy (Whittemore and Knafl 2005). Additionally, this broad method of research review encouraged and allowed for inclusion and synthesis of a diverse range of methodologies (both empirical and theoretical literature), capturing a variety of perspectives towards informing the research question (Whittemore and Knafl 2005).

3.1 Search Strategy

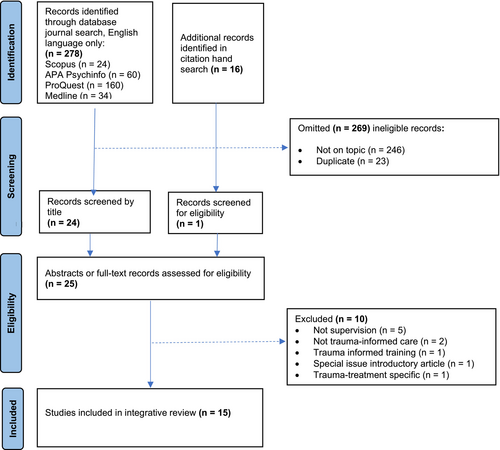

Results of the review process are presented according to a modified set of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) as described by Tricco et al. (2018). Stage 1 identifies literature sourced by title, stage 2 screening of literature abstract, stage 3 indicates literature included for eligibility following full article review, stage 4 identifies the literature sources included for this integrative review. All screening stages were conducted by one author and revised with co-authors to increase selection rigour.

3.2 Data Search

Systematic searching (between May and July 2022) of the Scopus database using the keyword search terms ‘nurs*’ AND ‘supervis*’ AND ‘trauma informed’. Filters were added for academic journals and English language. The same search terms were then used to systematically search three further databases: APA Psychinfo, ProQuest and Medline. The outcome of this search was poor, with only two eligible results identified at title review that were then excluded at abstract review as did not relate to supervision strategies.

Advice was sought from a University Librarian regarding search terms and electronic database searching. No additional keywords were identified during the librarian assisted MESH search, and to expand results obtained, the search term ‘nurs*’ was removed. The aim being to identify research from allied healthcare perspectives that may inform nursing supervision practice. This updated search criteria yielded a total of 278 journal articles across the same four databases. Initial screening was completed to evaluate findings against inclusion and exclusion criteria, duplicate articles were removed, resulting in 24 articles to review further for eligibility assessment.

To maximise the number of eligible studies, a hand search was then conducted using reference lists of relevant articles to identify further published research. Sixteen entries were identified in the reference list of eligible articles that discussed supervision and trauma (or the effects of trauma such as vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress), though only one reference (grey literature) was found in the hand searches warranted inclusion. See Table 1 for an overview of the initial search results.

| Source | Search area | Coverage | Keywords | Hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | Keyword | 2014–2022 | supervise* AND trauma-informed | 24 |

| APA Psychinfo | Keyword | 2011–2022 | supervis* AND trauma-informed | 60 |

| Proquest | Abstract | 2008–2022 | supervis* AND trauma-informed | 160 |

| Medline | Keyword | 2013–2022 | supervis* AND trauma-informed | 34 |

| Hand search | Title | 2014–2022 | supervis* AND trauma-informed | 16 |

| Total | 294 |

3.3 Inclusion Criteria

Literature published in English language that related to trauma-informed supervision in adult healthcare settings were included if they identified a specific ‘trauma-informed care’ framework.

No limitation of dates was imposed; all selected results were published within the last 8 years, coinciding with the development and publication of the trauma-informed care framework and guidelines (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014), and seminal work on trauma-informed supervision by Berger and Quiros (2014).

3.4 Exclusion Criteria

Literature related to a specific trauma response only, such as ‘compassion fatigue’, ‘secondary traumatic stress’, ‘burnout’ or ‘vicarious trauma’ were excluded. Though these experiences may be the consequence of providing trauma-informed care for healthcare professionals, they do not encompass the full principles and practice of the TIC framework. Literature related specifically to trauma training or trauma specific treatment models were also excluded.

Results that related to forensic, justice, corrections, probation, parole, disaster, religious and peer support settings were also excluded, as were those that relate to child or youth practice areas.

3.5 Data Evaluation

Figure 1 summarises the review process. During the screening process, 269 items were omitted as they did not meet selection criteria or were duplicate records. Eligibility screening occurred for the remaining 25 articles, 10 of which were excluded as did not specifically refer to supervision practices related to trauma-informed care or practice. The remaining 15 pieces of literature were selected (see Table 1). The intention of this integrative review was to include all literature that met the inclusion criteria. Whittemore and Knafl (2005) highlight the complexity of undertaking a quality appraisal when including a diverse range of literature and for this reason the authors chose not to undertake a quality appraisal.

3.6 Data Analysis

To identify and report themes identified within the research data, a reflexive thematic analysis method was utilised. This inductive method, described by Braun and Clarke (2021), allowed for coding and theme development based on exploration, interpretation and reporting of patterns in the content of the data analysed. Braun and Clarke (2021) describe six phases to guide thematic analysis in a recursive process. The first was to familiarise oneself with the dataset, reading the data multiple times to become well acquainted with its content. During the second coding phase, the data set was read again, this time creating labels which capture important features within the literature. For this review, the coding phase was repeated three times and generated a total of 126 codes. The third phase was to generate initial themes; the codes were grouped into broad categories (potential themes) of shared meaning. During the fourth and fifth phases, the potential themes were reviewed by all authors for congruence with the research question, and the themes (n = 3) and subthemes (n = 7) were defined and named based on their focus. The final phase was to write up the data, weaving it into a narrative that conveys the context of the findings in relation to existing literature. The final discussion chapter presents this narrative.

4 Findings

The review included 15 articles, all published in the USA. Five articles were published in a 2018 ‘special issue’ on trauma-informed supervision in ‘The Clinical Supervisor’ journal. The articles provided discussion on provision of trauma-informed supervision from social work, therapist and counselling perspectives. Four were identified as original research articles; three were qualitative papers exploring the supervisor perspective (Berger and Quiros 2016) and actions (Borders et al. 2022; Wong and Leung 2021). The fourth being the development of a trauma-informed practice supervision scale to understand the salient features of trauma-informed supervision (Cook, Wind, and Fye 2022). The remaining articles include a competency framework (NCTSN 2018), personal reflection (Courtois 2018; Radis 2020) and discussion papers (Berger and Quiros 2014; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Jordan 2018; Knight 2018; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018). See Table 2 for a description and summary of the literature included in the review.

| Article title, author, year | Design | Country | Setting | Study aims | TIC model used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervision for trauma-informed practice (Berger and Quiros 2014). | Discussion paper | USA | Professional health practitioners | To discuss how supervision strategies and principles can be adapted towards mastery of TIC practices. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

| Best practices for training trauma-informed practitioners: Supervisors' voice (Berger and Quiros 2016). | Qualitative study—12 participants, content analysis. | USA | Mental health personnel | To identify what trauma-informed supervisors consider to be best practice for teaching TIC. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

| The intersection of identities in supervision for trauma-informed practice: Challenges and strategies (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018). | Discussion paper | USA | Not identified | To discuss the role of intersectionality in trauma-informed supervision. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

| Trauma-informed supervision of trainees: Practices of supervisors trained in both trauma and clinical supervision (Borders et al. 2022). | Qualitative. Semi-structured interview of 9 supervisors who have formal training in both trauma work and clinical supervision. | USA | Counselling | To identify how trauma-informed supervisors respond to novice trainees within a supervision session. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) |

| Development of the trauma-informed practice scales—supervision version (TIPS-SV) (Cook, Wind, and Fye 2022). | Instrument development | USA | Counselling | To develop a trauma-informed supervision assessment scale to measure and capture supervisee perceptions of supervisor. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) |

| Trauma-informed supervision and consultation: Personal reflections (Courtois 2018). | Opinion piece | USA | Therapy | To convey how a trauma-informed supervisor promotes resilience and post-traumatic growth when working with therapists who experience countertransference and vicarious trauma. | Nil |

| Trauma-informed supervision in deployed military settings (Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018). | Discussion | USA | Military health care providers (medical) | To discuss and propose a trauma-informed supervision model for use in deployed military health settings. | ‘In extremis’ |

| Trauma-informed supervision: Clinical supervision of substance use disorder counsellors (Jones and Branco 2020). | Discussion | USA | Substance use disorder counsellors | To describe secondary traumatic stress vulnerabilities for substance use disorder counsellors and propose a trauma-informed supervision model for use in clinical supervision sessions. | Eco-systemic trauma development model |

| Trauma-informed counselling supervision: something every counsellor should know about (Jordan 2018). | Discussion | USA | Counselling | To present the ‘eco-systemic trauma development model’ for use within trauma-informed supervision. | Eco-systemic trauma development model |

| Trauma-informed supervision: Historical antecedents, current practice and future directions (Knight 2018). | Discussion | USA | Social work | To describe the evolution of trauma understanding; includes discussion of the nature of trauma-informed practice, trauma-informed care and trauma-informed supervision. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

| Reflections on facilitating a trauma-informed clinical supervision group with housing first staff (Radis 2020). | Reflection | USA | Mental health professionals | Present reflections on integrating TIC and resilience building during bi-weekly group supervision sessions. | Not discussed |

| Using the secondary traumatic stress core competencies in trauma-informed supervision (The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) 2018). | Competency Framework | USA | Workers exposed to secondary trauma | Present a competency framework for use as a developmental and assessment tool for trauma-informed supervision. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) |

| Reflective practices for engaging in trauma-informed culturally competent supervision (Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018). | Discussion | USA | Mental health | To review, discuss and present cultural competencies for trauma-informed supervision. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

| Trauma-informed supervision: Counsellors in a Level I hospital trauma center (Veach and Shilling 2018). | Discussion and case example | USA | Counselling | To examine the implementation of trauma-informed supervision in a hospital trauma setting with emphasis on substance use and post-traumatic stress responses. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) |

| Trauma-informed practice and supervision for volunteer counsellors of online psychological support groups during the impact of COVID-19 (Wong and Leung 2021). | Qualitative—content analysis of supervision session recordings | USA | Counselling | To identify questions, themes and emotions arising during trauma-informed supervision sessions. | Harris and Fallot (2001) |

4.1 Themes

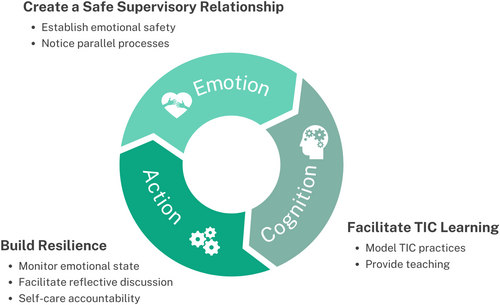

From the thematic analysis process (Braun and Clarke 2021) three interconnected themes were identified that aligned with a tri-phasic ‘emotion–cognition–action’ professional supervision sequence presented in the literature (Borders et al. 2022). The first ‘emotion’ stage refers to providing a sense of safety and stabilisation within the supervision relationship, considered a precursor for the second phase. ‘Cognition’ refers to engaging the learning brain, and ‘action’ refers to creation of an action plan to move forward.

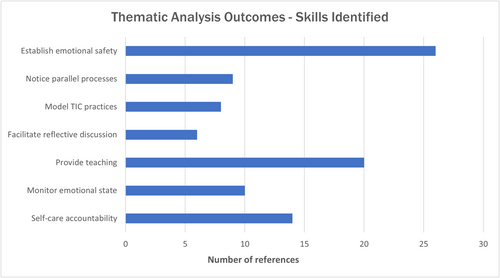

The skills identified (codes) from the included studies were grouped to form seven subthemes as can be seen in Figure 2. Whilst naming the subthemes, consideration was given to the research aim of identifying skills and strategies a trauma-informed supervisor can utilise. For this reason, each subtheme begins with a verb to indicate how the supervisor can apply the findings.

Borders et al. (2022) proposed the utility of these emotion–cognition–action sequences as both a template for a supervision session and way to model a clinical session structure that the supervisee could employ in their own practice. The literature review themes (and corresponding subthemes) are presented in a way that echoes this sequence; create a safe supervisory relationship, facilitate TIC learning and build resilience—these can be seen graphically in Figure 3 and are presented in more detail within Table 3.

| Emotion | Cognition | Action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme aim | To prioritise the development and maintenance of a strong supervisory relationship as the foundation towards a safe, supportive, empowering and validating space where the supervision relationship itself becomes a mechanism for change (all literature reviewed). | Facilitate learning (knowledge and skill development) of TIC framework (Berger and Quiros 2014, 2016; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Borders et al. 2022; Cook, Wind, and Fye 2022; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Jordan 2018; Knight 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). | Provide a reflective space to enhance self-awareness (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; NCTSN 2018) and support supervisee resilience against the impact of work-related challenges and secondary traumatic stress reactions (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jordan 2018; Radis 2020; Veach and Shilling 2018). |

| Focus/strategies |

Create a safe space to attend to the emotional needs of the supervisee (Berger and Quiros 2014, 2016; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Borders et al. 2022; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Knight 2018; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). Create an environment of trust where the supervisee feels safe to freely speak their mind regarding work related stressors and challenges and trauma related reactions with authenticity and vulnerability (Berger and Quiros 2014, 2016; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Borders et al. 2022; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Knight 2018; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). |

Use active learning strategies to model and facilitate understanding (teach) of the TIC framework (Berger and Quiros 2014, 2016; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Borders et al. 2022; Cook, Wind, and Fye 2022; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Jordan 2018; Knight 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). Experiential learning of TIC elements that may later be emulated in clinician–client interactions (Berger and Quiros 2016 and later literature citations). |

Facilitate reflective discussion to; enhance supervisee learning of the common psychological reactions to trauma; gain awareness of their own assumptions, biases, attitudes and beliefs (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Courtois 2018), and note where these unconscious reactions may be inconsistent with a trauma-informed understanding (NCTSN 2018). Educate and advocate for self-care activities that recuperate and replenish emotional reserves (Berger and Quiros 2016; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Jordan 2018; Radis 2020; NCTSN 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). |

| Supervisor skills described |

|

|

|

The emotional needs of the supervisee emerged as the primary subtheme within the literature reviewed (Berger and Quiros 2014, 2016; Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Borders et al. 2022; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jones and Branco 2020; Knight 2018; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018; Wong and Leung 2021). This clearly aligns with the ‘emotion’ phase of the sequence and its aim of enabling the supervisee to feel emotionally connected, safe and regulated. An emotionally safe relational space provides a secure base from which to engage in self-exploration (Borders et al. 2022; Cook, Wind, and Fye 2022; Veach and Shilling 2018); notice and attend to parallel processes (Berger and Quiros 2016; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018) and prepare for cognitive learning experiences (Berger and Quiros 2016; Borders et al. 2022; Courtois 2018).

By actively teaching and modelling the TIC framework the supervisor facilitates cognitive learning. The modelling of a TIC Lens was described as an experiential process, that the supervisee can then emulate in the clinician–client relationship (Borders et al. 2022; Jones and Branco 2020; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jordan 2018; Knight 2018; NCTSN 2018; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018). Through active teaching, the supervisee may develop skills in both recognising complex behaviour manifestations of trauma reactions and practice skills in providing TIC to address them (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Veach and Shilling 2018).

The collective subthemes of monitoring emotional state (for indirect trauma reactions), facilitating reflective discussions, and providing self-care accountability were grouped within the action theme. The aim being to use the supervision relationship to identify trauma-related behaviours (Berger and Quiros 2014; Borders et al. 2022; Jones and Branco 2020; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jordan 2018; Knight 2018; NCTSN 2018) and build resilience against the impact of working in trauma-affected environments (Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis 2018; Courtois 2018; Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018; Jordan 2018; Radis 2020; Veach and Shilling 2018). During their resilience-building discussion, Courtois (2018) remind us of the circular relationship within TIC practice by stating that engagement in resilience-building activities enhanced the stability of the supervisor–supervisee connection, adding to the emotional safety required for a strong supervisory relationship.

5 Discussion

The purpose of this integrative review was to identify the skills and strategies necessary to provide trauma-informed nursing supervision. The paucity of literature that explicitly discusses trauma-informed care in nursing supervision is a significant gap in evidence-based knowledge. To meet the research aim, the research findings were integrated with TIC principles and assumptions, and values from the Proctor (2010) Supervision Alliance model. This discussion notes where these frameworks intersect (both with each other and with mental health and addiction nursing competencies), and point towards additional skillsets that should be developed to provide effective trauma informed supervision.

Trauma-informed care is typically described in broad categories derived from the common principles of trauma-informed practice: safety, trust, choice, collaboration and empowerment (Harris and Fallot 2001; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014). The importance of being culturally responsive to gender, ethnicity and historical differences, and inclusion of peer support is further emphasised by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014), who also present four assumptions of TIC: realise, recognise, respond and resist re-traumatisation.

Multiple authors (Fleishman, Kamsky, and Sundborg 2019; Goddard et al. 2021; Isobel 2021; Portman-Thompson 2020; Young et al. 2019) discuss the TIC framework and provide guidance as to how the TIC assumptions can be expertly discussed, enacted and embodied in supervisory interactions. Realise includes awareness of the widespread prevalence of trauma; approaching the supervisee with the universal precaution approach (towards trauma) and curiosity about how the supervisee may be struggling. Recognise what trauma exposure looks like in your workplace; normalise nurse reactions to trauma and the signs and symptoms they may present; verbalise and validate the supervisee experience; be aware of cultural and power imbalances and intentionally act to reduce them; recognise the need for individualised interventions. Respond by prioritising the creation of a strong supervisory relationship; being present, compassionate and flexible; facilitating a safe emotional space and modelling the TIC model. Resist re-traumatisation by empowering the supervisee; supporting them to develop self-awareness; strengths-based discussions and intentional use of resilience-building/self-care strategies.

Whilst research by Simpson-Southward, Waller, and Hardy (2017) discredits the effectiveness of professional supervision (both for improving patient outcomes and supporting supervisee wellbeing), the trauma-informed care supervision literature is clear in recommending it as part of a comprehensive support system for staff working within a TIC model (Isobel 2021; Isobel and Thomas 2022; Sansbury, Graves, and Scott 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014; Wilson, Hutchinson, and Hurley 2017).

Though a vast number of supervision models have been proposed in the literature, the seminal ‘Supervision Alliance’ model described by Proctor (2010) was chosen for this discussion as an effective and contemporary supervision model. Identified as the most frequently cited supervision model for health professionals by Pollock et al. (2017) and utilised by Te Pou (2021) in their professional supervision guidelines, the supervision alliance model is evidence-based and has clear relevance to the New Zealand nursing supervision environment.

The supervision alliance model describes three core overlapping and flexible ‘normative, formative and restorative’ functions (Proctor 2010; Te Pou 2021). Proctor (2010) gives emphasis to the ‘restorative’ function, which focuses on equipping the supervisee to cope with the emotional impact of their work. With similarity to emotion being the precursor to cognitive and action in the tri-phasic sequence presented in this research results, Proctor (2010) consider it essential that the supervisee experience supervision as restorative (supportive) for formative (educational) and normative (administrative) tasks to be done well.

5.1 Emotion

A strong supervisory relationship was identified as the most important factor for trauma-informed supervision during the literature review. Berger and Quiros (2016) and Hiebler-Ragger et al. (2021) support the importance of attending to the attachment needs of the supervisee and suggest this could include bringing nurturing, supportive, gentle and attentive qualities to the relationship. Hartley et al. (2020) and Sweeney et al. (2018) suggest employing a skilful ‘use of self’ to develop a sense of belonging, mutuality and reciprocity within the relationship, creating an environment where the supervisee can challenge themselves and be held accountable as they move towards professional growth. Despite this discussion on practices that promote a strong supervisory relationship, the literature also presented argument that the evidence base for specific interventions to develop and maintain a strong therapeutic relationship is poor (Hartley et al. 2020; Timmins et al. 2020). In particular, it was reported that there is a deficiency of clear evidence-based strategies for navigating complex and emotionally challenging relationships (Hartley et al. 2020).

Equipping a nurse with skills to sustain the emotional energy required to provide TIC is paramount. MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie (2016) suggest this may be achieved via a supportive supervision relationship where emotion-based discussion is both modelled and encouraged by a self-aware and emotionally intelligent supervisor. Chikobvu and Harunavamwe (2022) note the value of a supervisor's ability to regulate their own, and then their supervisee's emotions. They describe this creates a sense of ‘being cared for’ within the supervision relationship, the outcome of which is collaborative problem solving and development of active coping skills. Therefore, in contrast to the scarcity of relational practices presented by Hartley et al. (2020), we have evidence that emotional intelligence is an entry point towards a strong therapeutic relationship (Chikobvu and Harunavamwe 2022; MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie 2016).

Robust literature discusses the impact of emotional intelligence in nursing practice, leadership and supervision (Chikobvu and Harunavamwe 2022; Delgado et al. 2017; Jimenez-Picon et al. 2021; MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie 2016; Mansel and Einion 2019). Jimenez-Picon et al. (2021) describe emotional intelligence as a form of social intelligence where a person has ability to control or regulate their own emotions, as well as those of others. The emotionally intelligent nurse supervisor can then use these skills to accurately read the emotions of supervisees, use this awareness to guide discussion and reflection, and support emotional regulation strategies (Delgado et al. 2017; Mansel and Einion 2019).

The centrality of relational competence is not unique to supervision. Guiding nursing competencies, ethics, standards, practice guidelines and reviews provide a range of targets a nurse is expected to demonstrate. Interpersonal relationships are one of four domains of nursing care (Nursing Council of New Zealand 2007). These domains include competencies of establishing, maintaining and concluding therapeutic relationships, working in negotiated partnerships and using appropriate communication methods within those relationships. Nursing ethics describe manaakitanga (to show care, respect and generosity towards others) to support clients to feel welcome and nurture a therapeutic relationship (New Zealand Nurses Organisation 2019). The second of six ‘mental health nursing standards of practice’ describes collaborative partnerships, based on strengths, hope and enhancing resilience as the foundation for therapeutic relationships (Te Ao Maramatanga; New Zealand College of Mental Health Nurses Inc 2012). In the mental health and addiction treatment guidelines published by Te Pou o te Whakaaro Nui (2018), the theme of manaakitanga appears again, alongside the values of respect, hope, partnership, well-being and whanaungatanga. The interrelating aim of these values is to develop effective partnerships with people who engage in mental health and addiction treatment. This relational emphasis not only exists across nursing competencies and standards, health literature also reports that a successful therapeutic alliance will have the greatest impact on outcomes, over and above any specific model or intervention used (Hartley et al. 2020; Hiebler-Ragger et al. 2021).

5.2 Cognition

Superior communication and relational skills are considered necessary for TIC (Isobel and Thomas 2022), but on their own are not sufficient according to Nizum et al. (2020). Their concern being that though relational competencies somewhat align with TIC principles, the use of these as TIC principles was not intentional and they believe the strength of TIC lies in the comprehension and intentional integration of the principles into practice.

This intentional integration of TIC principles and assumptions across all supervisory activities (applying a ‘trauma-informed lens’) was a key feature in this review's findings. Elements of this are expressed in each of the Supervision Alliance Model functions where the supervisor is responsible for supporting the supervisee to understand and apply the relevant professional competencies and frameworks (normative): providing experiential learning—a reflective learning process that provides the opportunity for the nurse to experience the theory that is being presented (formative) and offering emotional support (restorative)—based on principles of safety, trust, empowerment and collaboration. By emphasising cognitive and experiential learning and with parallels to the TIC principles, the supervision alliance model provides a framework for the trauma-informed supervisor to meeting the cognitive supervision needs of the nursing supervisee.

5.3 Action

Proctor (2010) and Te Pou (2021) describe supervision strategies to support supervisee emotional wellbeing and safety that most closely align with the action phase of the trauma-informed supervision responsibilities. With an emphasis on enhancing self-awareness and resilience, these restorative actions include establishing a safe environment, monitoring for signs of stress or secondary trauma reactions, identifying coping strategies and solution focussed strategies for improving wellbeing. These actions also correspond with and support the TIC assumption that care should resist re-traumatization (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2014).

The supervision alliance model facilitates development of self-awareness by promoting reflective practice; a process whereby one learns through discussion of one's practice and competence with another (Te Pou 2021). Reflection relies heavily on a safe interpersonal space in which the supervisee feels comfortable to openly and without fear of judgement, disclose and question their thoughts about challenging situations (Isobel and Thomas 2022; MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie 2016; Timmins et al. 2020). The trauma-informed supervisor can take this opportunity to provide education around the common psychological reactions to trauma that arise (Johnson, Johnson, and Landsinger 2018), normalise and validate the supervisees experience, whilst identifying learning gaps and developing new insights that can improve practice (Borders et al. 2022; MacLaren, Stenhouse, and Ritchie 2016; Proctor 2010; Timmins et al. 2020).

Both the importance and poor implementation of resilience building was discussed by Berger, Quiros, and Benavidez-Hatzis (2018) and Borders et al. (2022), who place the onus on a trauma-informed supervisor to provide discussion, modelling and accountability towards improvement. Defined as one's personal capacity to deal with workplace demands and adversity, resilience building in nursing is at the core of self-care activities (Delgado et al. 2017). Though Isobel and Thomas (2022) reported that resilience interventions are poorly articulated, much of the secondary traumatic stress, burnout and compassion fatigue literature leads us towards development of internal resilience resources (Chikobvu and Harunavamwe 2022; Coaston 2019; Davys et al. 2017). Internal resilience practices increase a nurse's adaptive capacity, as opposed to general health practices or behaviours such as relaxation, exercise and supervision seeking activities. The emphasis being on mitigating the impact of trauma-informed nursing demands by building connections and boundaries, developing personal attributes such as optimism, empathy and insight and supporting self-efficacy towards engagement in such activities (Chikobvu and Harunavamwe 2022; Davys et al. 2017; Delgado et al. 2017; Goddard et al. 2021; Isobel and Thomas 2022; Stacey et al. 2017).

A key insight to surface is the intersection of emotional intelligence and resilience-building actions. Strategies a supervisor utilises to strengthen their emotional competence and build a strong supervisory relationship are the very same practices that can be utilised by a supervisee to develop internal resilience (Chikobvu and Harunavamwe 2022; Delgado et al. 2017). The health professional resilience literature gives hints as to which skills may be of value to enhance emotional intelligence and resilience, with themes of self-compassion, mindfulness and grounding practices emerging.

Self-compassion is the directing of compassion (feelings of kindness and empathy towards uncomfortable emotional states such as uncertainty, suffering or failure) towards oneself (Coaston 2019; Jimenez-Picon et al. 2021; Neff et al. 2020). Self-compassion is considered a core relational attitude and is valued as a state that sends a message of warmth, connection and comfort towards others. Neff et al. (2020) sought to understand how self-compassion can be used in healthcare communities as protection against emotional suffering. Amongst their findings is acknowledgement that self-compassion enables the clinician to use emotional regulation in moments of distress and provide a presence that feels safe and calm.

Mindfulness is a tool to anchor one's awareness and attention in the present moment, increasing one's ability to be therapeutically present (Coaston 2019; Jimenez-Picon et al. 2021; Stacey et al. 2017). A mindful supervisor notices sensations, thoughts and emotions as they arise. Over time they develop the ability to respond with equanimity, taking a balanced perspective and responding appropriately rather than giving an emotionally driven reaction. During a systematic review to explore emotional intelligence and mindfulness as protective factors for healthcare professionals, Jimenez-Picon et al. (2021) positively linked mindfulness to an increased capacity to be present with uncomfortable emotions and reduce emotional reactivity—buffering against the impact of distressing emotional events.

Being grounded is an emotional regulation tool, where one notice's and explore's their environment, physical and emotional state (Borders et al. 2022; Radis 2020; Stacey et al. 2017; Varghese, Quiros, and Berger 2018). The literature directs us towards breathwork-based grounding skills. Describing its value as a pause, creating a moment to think before acting, breathwork was considered a useful bridge or transition between clinical practice and the supervisory space.

To be therapeutically present through the practices of mindfulness, self-compassion and grounding practices, the supervisor must have a solid understanding of and willingness to model these practices (Coaston 2019; Stacey et al. 2017). Supervisors, and subsequently supervisees, who incorporate these practices into their own lives are equipped with increased emotional regulation, develop a transferable coping strategy, and are better able to model these skills to others.

5.4 Trauma Informed Supervision

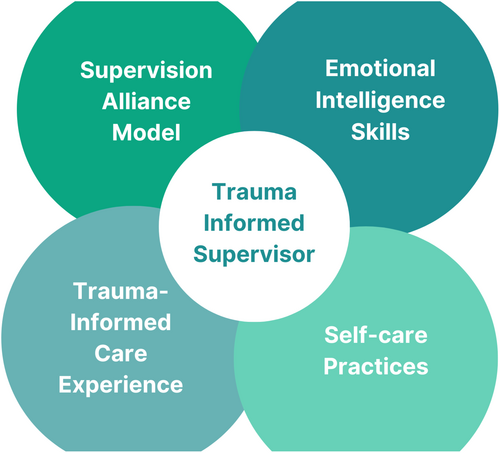

These findings and discussion point us towards skills a trauma-informed supervisor can develop to optimise their supervisory practice. Essential skills include familiarity and experience with the supervision alliance model, and the TIC framework. Developing proficiency in emotional intelligence and a willingness to adopt self-care practices will strengthen the trauma-informed supervisor practice by; advancing relational skills; enhancing ability to respond to supervisee vicarious trauma responses and modelling resilience practices to support supervisee emotional wellbeing. These four competencies are depicted in Figure 4.

6 Conclusion

This integrative review identified fundamental knowledge, skills and personal practices a nurse supervisor can implement to develop competence in trauma-informed supervision. The findings revealed an emotion–cognition–action sequence that aligns with the restorative, normative and formative functions of the supervision alliance model and principles and assumptions of the TIC framework. The trauma-informed lens concept was introduced and discussion attests that this lens permeates every action and interaction between the supervisor and supervisee. Actions towards strengthening emotional intelligence and resilience were described and parallels drawn to how these same resilience-building practices also act to strengthen one's relational skills.

7 Relevance for Clinical Practice and Future Development

Trauma-informed supervision integrates the fundamental elements of trauma-informed care into the supervisor–supervisee relationship. The trauma-informed supervisor has skills in facilitating reflective discussion through a trauma-informed lens to meet ‘formative’ supervision functions by deepening supervisee self-awareness and trauma-informed learning. The integration of relational competencies provides opportunity for the trauma-informed supervisor to model the safety elements of the TIC framework and meet their ‘restorative’ (emotionally supportive) responsibilities as a clinical supervisor.

This review built on a tri-phasic emotion–cognition–action sequence proposed by Borders et al. (2022) to provide a framework for use both within a supervisory session and that the trauma-informed supervisee can use to structure their own clinical interactions.

At the individual level, nursing supervisors who wish to become more trauma-informed in their supervision practice are encouraged to seek professional development on the TIC framework. They should also seek and apply development opportunities to strengthen emotional intelligence, such as grounding, mindfulness and self-compassion practices. The onus is then on the nurse-supervisor to develop a personal practice of these skills, creating the emotional intelligence and resilience required to meet trauma-informed supervision demands (Coaston 2019).

Organisations that wish to strengthen their TIC capability and meet their health and safety responsibilities towards staff emotional wellbeing should ensure regular access to professional supervision for all nurses (Young et al. 2019).

Research to understand how nursing supervisors apply the TIC assumptions could enhance our understanding of the supervision-TIC intersection. Similarly, research to ascertain additional emotional intelligence-building strategies and resilience-building activities could inform future supervision practice goals.

Finally, this review is a preliminary attempt to identify the strands that inform trauma-informed supervision. It is the authors' hope that future research endeavours may build on the current findings and include the development, implementation and assessment of a trauma-informed supervision model and competencies specific to nursing practice.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. K.M. drafted the paper, conducted the search, data extraction, quality assessment, synthesis and discussion of the findings. H.B. and D.N. assisted the search and contributed to the synthesis and discussion of the findings and preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge with gratitude Te Pou, the National Workforce Centre for Mental Health, Addiction and Disability in New Zealand, who provided funding for postgraduate training towards clinical leadership in nursing practice. Te Pou were not involved in the review process or decision to publish. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Auckland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Auckland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in University of Auckland Research Repository—ResearchSpace at https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/, reference number https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/66022.