Perceptions of candidate strength in job recruitment: Does candidate race moderate the attractiveness bias in White women?

Abstract

The attractiveness bias suggests that people who are more attractive will be positively favored across life outcomes. This study sought to test whether candidate attractiveness, sex, and race, affect perceptions of candidate strength in a job recruitment task. In total, 338 White women (Mage = 20.94 ± 5.65) were asked to make judgements of a potential candidate for an administrative job (resume with candidate photograph). The vignettes differed in terms of candidate ability (strong/weak), sex (male/female), race (Black/White), and attractiveness (attractive/less attractive). Participants rated perceived candidate strength and likelihood to invite for interview. Results showed no significant main effects for attractiveness. However, there was a significant interaction for target attractiveness and race, such that attractive/White candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than less attractive/White candidates. There was also a significant main effect for race such that Black candidates were rated as stronger and more likely to be interviewed. Sensitivity analyses (with nonheterosexual women removed from the sample) also showed a main effect for target sex such that female candidates were favored over male candidates. Overall, these findings provide evidence that attractiveness, sex, and race have important, albeit complex, effects on hiring decisions in the workplace.

Highlights

Highlights

-

A vignettes study testing the effects of candidate sex, race, and attractiveness in a job recruitment task

-

Attractive candidates more likely to be invited for interview but only if they are the same race as the recruiter

-

Women more likely to be invited for interview by heterosexual women recruiters

-

Black candidates generally favored over White candidates

Practitioner points

(a) What is currently known

- •

Attractiveness, race, and sex have all been identified as important in job recruitment

- •

Little is known about how these factors might interrelate in job recruitment

(b) What the paper adds

- •

Attractive/White candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than unattractive/White candidates

- •

White women rated Black candidates as stronger and more likely to invite to interview

- •

Female candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than male candidates

- •

When applications are weaker Black women are favored over White women and when applications are stronger Black men are favored over White men

(c) Implications for practitioners

- •

Practitioners should educate organizations on the role of attractiveness in hiring decisions

- •

Practitioners should also educate organizations about how attractiveness interacts with race in hiring decisions

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the greatest challenges of organizations is developing efficient and effective recruitment procedures to employ the most suitable candidates (Paustian-Underdahl & Walker, 2016). In a cultural landscape of affirmative action working to counterbalance historical discrimination, there is a moral expectation to uphold fair and equitable hiring practises which treat candidates fairly across the board. The consequences of poor recruitment processes range from diminished profits and reduced organizational growth to high level discrimination legal cases (Rahman & Islam, 2012). Most industrialized nations have implemented legislation that aims to curtail unlawful discrimination on the basis of age, disability, race, sex, intersex status, gender identity, and sexual orientation (see, e.g., Australian Human Rights Commission, 2020). However, unconscious biases held by employers can influence the selection process and hiring decisions (Huffcutt, 2011). In particular, biases surrounding sex, race and physical attractiveness have been documented as contributing factors to the decision making process in job recruitment (Maestripieri et al., 2017). However, less is known about how these factors might interconnect to affect hiring decisions. This study sought to test how sex, race, and physical attractiveness interrelate in decision making for a job recruitment task.

When forming initial impressions, people draw heavily on salient visual cues such as sex, ethnicity, and attractiveness (Hosoda et al., 2003). The idea that those who are more physically attractive possess more desirable character traits has been termed the attractiveness bias (Dion et al., 1972). The attractiveness bias reflects the tendency for more physically attractive individuals to be perceived as having more positive attributes such as sociability, honesty, intelligence, and life success (Dion et al., 1972). Over the last 50 years, much research has supported the existence of an attractiveness bias in a variety of contexts. For example, meta-analytic reviews have found that more attractive individuals are given better grades in academia, are less likely to be given guilty decisions in court verdicts, and are more likely to be offered employment in hiring decisions (Devine & Caughlin, 2014; Eagly et al., 1991; Hosoda et al., 2003; Langlois et al., 2000; Mazella & Feingold, 1994). It has been noted that physical attractiveness can often be the deciding factor when faced with applicants of relatively equal qualifications (Hosoda et al., 2003).

In addition to physical attractiveness, there is also a considerable amount of research on sex and race discrimination in the workplace. Historically, sex-based discrimination has resulted in women receiving lower wages, fewer leadership positions, and a longer timeframe to advance their careers (Stamarksi & Son Hing, 2015). In terms of hiring decisions, meta-analyses have demonstrated that given the same qualifications, men tend to be preferred over women (Olian et al., 1988). However, this effect is contingent on job type, such that men tend to be preferred for “male-type” jobs (e.g., jobs involving leadership) whereas women tend to be preferred for “female-type” jobs (e.g., jobs involving childcare) (Davison & Burke, 2000). In terms of race discrimination, there is evidence that interviewers tend to favor same-race candidates (Veit et al., 2022; Waddoups et al., 1995) as well as particular races (Rattan et al., 2019). A meta-analysis of 43 field-based experiments found that ethnic minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for interview (Zschirnt & Ruedin, 2016). There is some evidence that sex discrimination in the workplace has decreased over time (McCord et al., 2018), but mixed evidence on race discrimination having decreased over time (McCord et al., 2018; Quillian et al., 2017).

1.1 The current study

Research on the attractiveness bias remains convoluted due to inconsistent results and context dependency (Lee et al., 2017; Nault et al., 2020). Research has started to explore how target sex or race might moderate the strength of the attractiveness bias. Initial research indicated that the attractiveness bias was not moderated by target sex—men and women would favor both attractive men and women (Eagly et al., 1991). However, more recent research indicates that this might not be the case. In research on job interviews, an attractiveness bias was observed for opposite-sex candidates, but participants discriminated against highly attractive same-sex candidates (Agthe et al., 2010, 2016). Similarly, in research on punishment, same-sex targets are punished more severely than opposite sex targets when the target is attractive, but this pattern is reversed when the target is less attractive (Li & Zhou, 2014; Mackelprang & Becker, 2017). This pattern of results is thought to have an evolutionary foundation, such that (at least for heterosexual persons) an attractive same-sex candidate is more likely to be perceived as a potential mating rival, inducing a threat response including emotions such as jealousy (Agthe et al., 2016).

In terms of race, some research has found that sex and race moderations do not predict hiring decisions (Marshall et al., 1998), whereas other research has found that an attractiveness bias (for opposite-sex candidates) emerges for same-race targets but not for other-race targets (Agthe et al., 2016). People from different ethnicities and cultures tend to agree on whom they consider attractive (Coetzee et al., 2014). However, the attractiveness bias might not be as strong when members of a different ethnicity are evaluated (Agthe et al., 2016). This is thought to occur because (1) members of other ethnic groups are less likely than same-ethnicity targets to be seen as potential mates and romantic rivals, (2) other-race targets are potentially less relevant for appearance-based social comparison because they appear less similar to the evaluator, and are therefore less likely to elicit self-other comparison, and (3) because people are more sensitive to mating-related cues in targets who share their own race (Agthe et al., 2016). This sensitivity to mating-related cues in same-race targets might result from socialization factors, such as greater family acceptance for a partner of the same race (Agthe et al., 2016).

The purpose of the current investigation was to further explore the moderating roles of sex and race in job recruitment. We explore both perception of candidate strength and likelihood to invite for interview as dependent variables. Perception of candidate strength should relate strongly to likelihood to invite for interview, but it can be useful to explore these as separate variables. That is, recruiters might (either consciously or unconsciously) use information other than perception of candidate strength when deciding whether or not to invite a candidate for interview. Therefore, it can be useful to explore likelihood to action (invitation) in addition to perception of strength. Moreover, being invited to interview is often the first barrier faced by job applicants, and therefore studying bias at this point is especially relevant to job recruitment. In addition, we include both a stronger applicant (strong resume) and a weaker applicant (weak resume) in the study design, to provide a benchmark variable for estimating the magnitude of bias effects. In an ideal world, where sex, race, and attractiveness are not factored into perceptions of job applicants, perceptions of candidate strength and likelihood to invite for interview should only differ across this objective resume strength variable.

Based on previous research (e.g., Agthe et al., 2016), we hypothesized a moderation effect for attractiveness and sex, such that participants (all women) would favor attractive male candidates over less attractive male candidates, but favor less attractive female candidates over more attractive female candidates (H1). We also hypothesized a moderation effect for attractiveness and race such that participants (all White women) would favor attractive White candidates over less attractive White candidates, but not discriminate between attractive and less attractive Black candidates (H2). Based on these two hypotheses, we also hypothesized a three-way interaction effect such that the tendency to favor attractive male candidates over less attractive male candidates (and favor less attractive female candidates over more attractive female candidates) would emerge for White candidates but not Black candidates (H3). In addition, while attractiveness is valued across sexes it is most valued in potential mates (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Therefore, the sexual orientation of participants might also be an important consideration in hiring decisions. In light of this, we explore data both with and excluding participants who identified their sexual orientation as nonheterosexual to check the robustness of results.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Sample size was determined using the statistical software package GPower 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007). For a four-way fixed effects analysis of variance with a medium effect size Cohen's f = 0.25, α error probability .05, and statistical power 1–β error probability .80, the total sample size required is 320. A medium effect size was targeted based on effect sizes identified in previous research exploring moderators of the attractiveness bias (e.g., Allen et al., 2019; Swami et al., 2017). Due to the potential confounding factors of participant sex and race (see Agthe et al., 2016), only White women were included as participants in the current study. All participants were undergraduate psychology students recruited from a single university. Research has supported the validity of using student participants in place of professional evaluators in vignette research, with no significant differences observed between ratings (Hosoda et al., 2003). In total, 338 White women (age range = 17 to 57 years; Mage = 20.94, SD = 5.65) agreed to take part in the research. In total, 270 reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual or straight, and 68 reported their sexual orientation as lesbian, bisexual, or other.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Chicago face database

In total, eight neutral expression images were obtained from the Chicago Face Database (CFD; Ma et al., 2015) and are digital passport-style photos with no smiling or background. The four targets representing White male and female attractive and less attractive candidates were those used in previous research (Allen et al., 2019; Swami et al., 2017). Images of two White men (CFD image numbers: WM-004 and WM-236) and two White women (CFD image numbers: WF-022 and WF-229) were used. An additional four Black targets were selected and were matched on age (20–26 years) and attractiveness ratings. Images of two Black men (CFD image numbers: BM-043 and BM-023) and two Black women (CFD image numbers: BF-002 and BF-044) were used. The attractiveness scores for these images were 4.66 (WM-004), 2.04 (WM-236), 5.09 (WF-022), 2.68 (WF-229), 4.85 (BM-043), 2.18 (BM-023), 4.89 (BF-002), and 2.11 (BF-044). Interrater reliability of attractiveness ratings, scored from one (not at all attractive) to seven (extremely attractive), were high (α = .998; Ma et al., 2015).

2.2.2 Vignettes

Participants were presented with a vignette of a job advertisement that described recruitment for a nonmanagerial role in a marketing company. The advertisement shown to participants was as followed:

Knauf Australia now has an exciting Graduate opportunity for a dynamic Marketing Assistant to join the team on a full-time basis with a competitive base salary circa $55,000–$60,000 plus super! This role requires the individual to provide support to managers, other employees, and office visitors by handling a variety of tasks to ensure that all interactions between the organization and others are positive and productive. Candidates should be able to assist management and all visitors to the company by handling office tasks, providing polite and professional assistance via phone, mail, and e-mail, making reservations or travel arrangements, and generally being a helpful and positive presence in the workplace. Marketing assistants must be comfortable with computers, general office tasks, and excel at both verbal and written communication.

The Person:

Formal qualification would be highly regarded, particularly in relevant fields

Experience in a similar position for a period of 1–2 years

Confidence to work autonomously with a professional and approachable attitude, be innovative and proactive

Demonstrated active time management skills and handling various priorities

Two sample applications were developed to reflect stronger and weaker applicants that differed on education and work experience. These differences included school and university education, and previous work experience (see Supporting Information). Target photographs were attached to the job applications, where each image (eight in total) was attached to both a strong and weak application, resulting in a total of 16 variations of the application. The applications varied on application strength (strong/weak), attractiveness (attractive/less attractive), sex (male/female), and race (White/Black). After reading the job advertisement and one application, participants were asked to rate the applicant strength and likelihood to interview. Participants responded to the questions “Please rate how strong you consider this applicant” from one (very weak) to seven (very strong) and “As an employer, what is the likelihood that you would invite this candidate to interview for the position?” from one (not at all likely) to seven (extremely likely). These questions are consistent with those used in previous vignette studies (e.g., Marshall et al., 1998).

2.2.3 Pilot studies

Before conducting the study, pilot research was conducted to detect potential ceiling and floor effects. A nonphotographed version of the strong and weak vignettes were presented to participants who respond to the two questions. In Pilot Study 1, 20 participants were asked to read the job advertisement and the job application (10 received the weaker job application and 10 received the stronger job application), and answer the two questions on strength and likelihood to interview. For strength of applicant, the weaker applicant received a rating above the midpoint (M = 4.60, SD = 1.43), with the strong applicant receiving an even higher rating (M = 5.70, SD = 0.82). For likelihood to interview, the weaker applicant again received a rating above the midpoint (M = 4.80, SD = 1.40), and the strong applicant received an even stronger rating (M = 6.30, SD = 0.95). These results indicate potential ceiling effects and so the applications were adjusted to “weaken” both applicants.

In Pilot Study 2, 18 participants received the adjusted vignettes (nine received the weaker job application and nine received the stronger job application). For strength of the applicant, the weak application received a rating at the midpoint—lower than in the first pilot study (M = 4.00, SD = 1.22), and the strong application received a stronger rating (M = 5.89, SD = 0.60). For likelihood to interview, the weak application received a rating above the midpoint (M = 4.44, SD = 1.67), and the strong application received a stronger rating (M = 6.33, SD = 0.70). These results indicated only minor changes from the original pilot study and so the vignettes were again adjusted to weaken both applicants.

In Pilot Study 3, 10 participants received the adjusted vignettes (five received the weaker job application and five received the stronger job application). For strength of the applicant, the weak application received a rating above the midpoint (M = 4.20, SD = 1.79), and the strong application received a stronger rating (M = 5.80, SD = 1.64). For likelihood to interview, the weak application received a rating above the midpoint (M = 4.40, SD = 1.81), and the strong application received a stronger rating (M = 6.20, SD = 1.30). The scores for the two vignettes remained relatively high but there appeared to be sufficient in-group variation and difference between the two candidate conditions to progress to the main study. Minor adjustments were made to the job advertisement in accordance with feedback received by participants. These changes aimed to elevate the job profile to an increased professional level role and in turn (slightly) lower the rating scores of the two candidates. The final vignettes are those presented in the Supporting Information.

2.3 Procedure

Before conducting the study, ethical clearance was obtained from a university research ethics committee. Participants were recruited from a single university and received course credit in exchange for their participation. Participants provided digital informed consent and provided information on sex, age, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Only participants that reported their sex as female and ethnicity as White were included in the study. Participants were informed that the aim of the study was to investigate factors influencing perceived strengths and hireability of job applications, and were randomly allocated 1 of 16 vignettes. They were instructed to imagine they were in a situation whether they had 20 job applications and needed to select 5 to be interviewed. They were then provided the job advertisement and a single application from 1 of the 16 vignettes and were asked to rate the applicants' strength and the likelihood of inviting the candidate for an interview. Once this was completed, participants were informed about the true purpose of the study. Participants completed the study online and unsupervised.

2.4 Analyses

Two 2 (target sex: female, male) x 2 (application strength: strong, weak) x 2 (target race: Black, White) x 2 (target attractiveness: attractive, less attractive) between-subjects analysis of variance were computed on the two dependent variables of applicant strength and likelihood of interview. Homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene's test of equality of error variances, normality was checked through observations of data skewness (<±2.00 indicates a normal distribution), and potential outliers were identified through z-scores. One potential outlier was identified on the dependent variable likelihood to interview (z = 3.08). Analyses were run with and with and excluding this outlier to check the robustness of results (a sensitivity analysis). Homogeneity of variance was violated for both strength of applicant (p = .025) and likelihood to interview (p = .015). However, analysis of variance (ANOVA) is robust to violations of homogeneity of variance in larger sample sizes where minor departures from normality can often appear statistically significant (Blanca et al., 2017). Significant interaction effects were followed up using independent samples t-tests.

As opposite sex candidates are predicted to show a greater attractiveness bias (due to sexual attraction; see Agthe et al., 2016), this effect might be contingent on participant sexual orientation. Therefore, all analyses were re-run on a subsample of participants that described their sexual orientation as heterosexual or straight (N = 270). The subsample included 270 White women (age range = 17 to 57 years; Mage = 20.89, SD = 5.77). In the subsample, all data appeared normally distributed and z-scores revealed no potential outliers. Homogeneity of variance was confirmed for both strength of applicant and likelihood to interview. In terms of interpretation, an effect size d = 0.20 (η2 = 0.01) was considered small, an effect size d = 0.41 (η2 = 0.04) was considered medium, and an effect size d = 0.63 (η2 = 0.09) was considered large.

3 RESULTS

Descriptive statistics across the 16 conditions (varying on target application strength, target attractiveness, target race, and target sex) for perceived strength of applicant and likelihood to interview are presented in Table 1.

| Full sample (n = 338) | Subsample (n = 270) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived strength | Likely to interview | Perceived strength | Likely to interview | |||||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | n | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Weaker application | ||||||||||

| Attractive/Black/Female | 22 | 4.09 | 1.27 | 4.41 | 1.37 | 16 | 4.13 | 1.20 | 4.44 | 1.37 |

| Unattractive/Black/Female | 21 | 4.43 | 0.93 | 4.95 | 1.50 | 18 | 4.50 | 0.92 | 5.00 | 1.45 |

| Attractive/Black/Male | 23 | 3.65 | 1.11 | 3.61 | 1.53 | 18 | 3.61 | 1.20 | 3.33 | 1.53 |

| Unattractive/Black/Male | 23 | 3.61 | 1.41 | 3.48 | 1.48 | 20 | 3.35 | 1.23 | 3.25 | 1.29 |

| Attractive/White/Female | 22 | 3.73 | 1.16 | 3.64 | 1.50 | 19 | 3.74 | 1.20 | 3.68 | 1.53 |

| Unattractive/White/Female | 23 | 3.83 | 1.19 | 3.61 | 1.34 | 19 | 3.89 | 1.20 | 3.74 | 1.28 |

| Attractive/White/Male | 21 | 4.38 | 1.47 | 4.38 | 1.72 | 14 | 4.29 | 1.27 | 4.29 | 1.44 |

| Unattractive/White/Male | 19 | 3.26 | 1.05 | 3.11 | 1.37 | 13 | 3.46 | 1.20 | 3.38 | 1.56 |

| Stronger application | ||||||||||

| Attractive/Black/Female | 20 | 5.25 | 1.02 | 5.35 | 1.09 | 15 | 5.07 | 1.10 | 5.20 | 1.21 |

| Unattractive/Black/Female | 20 | 5.15 | 0.81 | 5.50 | 0.89 | 18 | 5.11 | 0.83 | 5.44 | 0.86 |

| Attractive/Black/Male | 20 | 5.35 | 0.99 | 5.70 | 1.13 | 16 | 5.25 | 1.00 | 5.63 | 1.15 |

| Unattractive/Black/Male | 20 | 5.45 | 0.89 | 5.55 | 0.83 | 15 | 5.47 | 0.99 | 5.53 | 0.92 |

| Attractive/White/Female | 24 | 4.92 | 1.18 | 5.42 | 1.18 | 20 | 5.10 | 1.17 | 5.60 | 1.10 |

| Unattractive/White/Female | 19 | 5.05 | 1.51 | 4.95 | 1.47 | 14 | 4.86 | 1.46 | 4.86 | 1.41 |

| Attractive/White/Male | 22 | 5.05 | 1.13 | 5.09 | 1.34 | 18 | 5.11 | 1.18 | 5.00 | 1.46 |

| Unattractive/White/Male | 19 | 4.74 | 0.73 | 4.84 | 1.07 | 17 | 4.71 | 0.77 | 4.88 | 1.11 |

3.1 Perceived strength of applicant

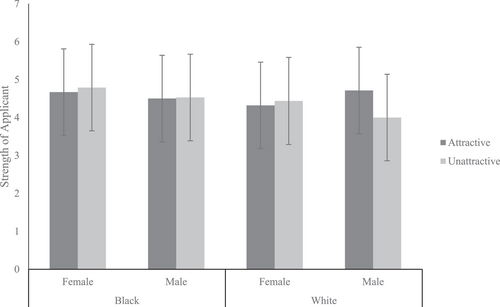

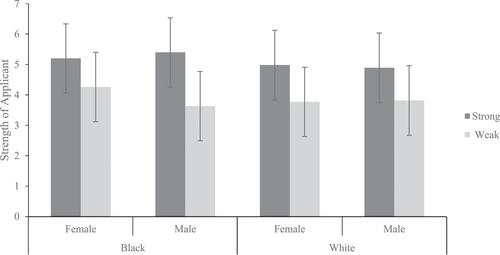

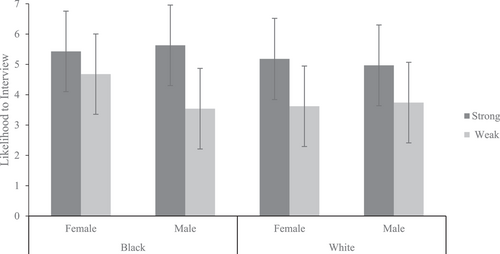

The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of target race, F(1, 337) = 4.16, p = .042, 2 = 0.01, with Black targets (M = 4.62, SE = 0.09) receiving higher ratings than White targets (M = 4.37, SE = 0.09). There was also a significant main effect of application strength, F(1, 337) = 100.33, p < .001, 2 = 0.24, such that strong applications were rated higher (M = 5.12, SE = 0.09) than weak applications (M = 3.87, SE = 0.09). There was no significant main effect found of target attractiveness, F(1, 337) = 8.12, p = .368, 2 < 0.01, or sex, F(1, 337) = 0.92, p = .338, 2 < 0.01. In terms of moderation effects, there were no significant two-way interaction effects for target attractiveness and target race, F(1, 337) = 2.23, p = .137, 2 = 0.01, target attractiveness and target sex F(1, 337) = 3.42, p = .065, 2 = 0.01, or target sex and target race F(1, 337) = 0.59, p = .444, 2 < 0.01. The three-way interaction effect for target sex, race and attractiveness was also nonsignificant, F(1, 337) = 2.21, p = .138, 2 = 0.01, and there were no significant interaction effects involving target application strength. These effects are depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

For the subsample of heterosexual participants (n = 270), the ANOVA again revealed a significant main effect for application strength, F(1, 269) = 76.80, p < .001, 2 = 0.23, with strong applications rated higher (M = 5.08, SE = 0.10) than weak applications (M = 3.87, SE = 0.10). There were no significant main effects found for target attractiveness, F(1, 269) = 0.72, p = .397, 2 < 0.01, target race, F(1, 269) = 1.44, p = .232, 2 = 0.01, or target sex, F(1, 269)= = 1.08, p = .300, 2 < 0.01. For moderation effects, there were no significant two-way interactions observed for target attractiveness and target race, F(1, 269) = 2.33, p = .128, 2 = 0.01, target attractiveness and target sex, F(1, 269) = 2.11, p = .148, 2 = 0.01, or target sex and target race, F(1, 269) = 0.99, p = .321, 2 = 0.01. The three-way interaction effect for target sex, race and attractiveness was also nonsignificant, F(1, 269) = 0.38, p = .539, 2 < 0.01. However, there was a significant three-way interaction for target sex, target race and application strength, F(1, 269)= = 4.93, p = .027, 2 = 0.02. However, analysis of simple effects showed that the interaction was nonsignificant on all levels of the independent variables indicating that this three-way interaction is probably not meaningful.

3.2 Likelihood to interview

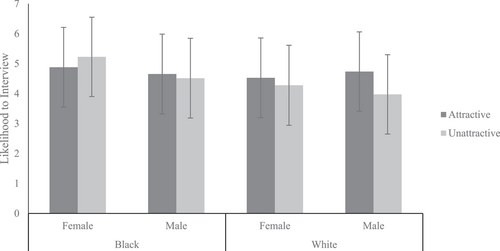

For likelihood to interview, there was a significant main effect for target race, F(1, 337) = 9.25, p = .003, 2 = 0.03, with Black targets (M = 4.82, SE = 0.10) being more likely to be invited to interview than White targets (M = 4.38, SE = 0.10). There was also a significant main effect for application strength, F(1, 337) = 93.89, p < .001, 2 = 0.23, with strong applications (M = 5.30, SE = 0.10) being more likely to be invited to interview than weak applications (M = 3.90, SE = 0.10). There was no significant main effects for target attractiveness, F(1, 337) = 1.93, p = .166, 2 = 0.01, or target sex, F(1, 337) = 3.18, p = .075, 2 = 0.01. For moderation effects, there was a significant two-way interaction for target attractiveness and target race, F(1, 337) = 4.43, p = .036, 2 = 0.01. This effect was such that attractive White candidates were more likely to be invited to interview (M = 4.63, SE = 0.14), than less attractive White candidates (M = 4.13, SE = 0.15), t(167) = 2.32, p = .022, d = 0.36, but there was no significant difference between attractive Black candidates (M = 4.77, SE = 0.14) and less attractive Black candidates (M = 4.87, SE = 0.15), t(167) = 0.45, p = .654, d = 0.07.

There were no significant two-way interaction effects for target attractiveness and target sex, F(1, 337) = 2.99, p = .085, 2 = 0.01, or target sex and target race, F(1, 337) = 2.12, p = .147, 2 = 0.01. There was also no significant three-way interaction between target attractiveness, target sex and target race, F(1, 337) = 0.00, p = .963, 2 < 0.01. However, there was a significant three-way interaction for target race, target sex and application strength, F(1, 337) = 8.36, p = .004, 2 = 0.03. Analysis of simple effects showed that this effect was such that, for stronger applications only, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for men, t(79) = 2.65, p = .010, d = 0.60. For weaker applications, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for women, t(86) = 3.47, p = .001, d = 0.75. These findings are depicted in Figures 3 and 4, and findings remained unchanged with one potential multivariate outlier removed from the sample.

For the subsample of heterosexual participants (n = 270), the ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for target sex, F(1, 269) = 4.33, p = .038, 2 = 0.02, with female candidates (M = 4.75, SE = 0.11) more likely to be invited to interview than male candidates (M = 4.41, SE = 0.12). There was also a significant main effect for application strength, F(1, 269) = 74.17, p < .001, 2 = 0.23, with strong applications (M = 5.27, SE = 0.11) more likely to be invited to interview than weak applications (M = 3.89, SE = 0.11). There was no significant main effect found of target attractiveness, F(1, 269) = 0.71, p = .401, 2 < 0.01, or target race, F(1, 269) = 3.49, p = .063, 2 = 0.01. For moderation effects, there was a significant two-way interaction effect for target sex and application strength, F(1, 269)= 3.95, p = .048, 2 = 0.02. This effect was such that female candidates (M = 4.22, SE = 0.15) were more likely to be invited to interview than male candidates (M = 3.56, SE = 0.16) when the application was weak, t(135) = 2.65, p = .009, d = 0.46. However there was no difference between female candidates (M = 5.28, SE = 0.16) and male candidates (M = 5.26, SE = 0.16) when the application was strong, t(131) = 0.35, p = .728, d = 0.06. There were no significant two-way interaction effects for target attractiveness and target race, F(1, 269) = 3.34, p = .069, 2 = 0.01, target attractiveness and target sex, F(1, 269) = 1.05, p = .307, 2 < 0.01, or target sex and target race, F(1, 269)=;= 2.48, p = .117, 2 = 0.10. There was no significant three-way interaction effect for target attractiveness, race and sex, F(1, 269) = 0.26, p = .610, 2 < 0.01. However, there was a significant three-way interaction effect for race, sex and application strength, F(1, 269) = 4.93, p = .027, 2 = 0.02. This effect was such that, for stronger applications, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for men, t(64) = 2.21, p = .031, d = 0.55. For weaker applications, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for women, t(70) = 3.09, p = .003, d = 0.74.

4 DISCUSSION

This study sought to test whether candidate attractiveness, sex and race, affect perceptions of candidate strength in a job recruitment task. Results showed no significant main effects for attractiveness. However, there was a significant main effect for race such that Black candidates were rated as both stronger and more likely to be invited for interview. There was also a significant interaction for target attractiveness and race, such that attractive/White candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than less attractive/White candidates, but with no attractiveness bias for Black candidates. Sensitivity analyses (with nonheterosexual women removed from the sample) also showed a main effect for target sex, such that female candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than male candidates, as well as an interaction effect for sex and application strength, such that female candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than male candidates but only when the application was relatively weak.

The finding that candidate attractiveness as a standalone variable did not predict perceived strength or likelihood to invite for interview is consistent with a body of research demonstrating that the attractiveness bias is context dependent (Lee et al., 2017; Nault et al., 2020). However, the hypothesized moderation effect for attractiveness and sex (H1: women would favor attractive male candidates over less attractive male candidates, but discriminate against attractive female candidates) was not supported. Thus, findings differ from previous work demonstrating moderation effects for sex and attractiveness (Agthe et al., 2010; Li & Zhou, 2014; Mackelprang & Becker, 2017). Facial processing and dual processing theory consider that visual cues associated with stigma (e.g., race and sex) are processed more rapidly and before other information (see e.g., Derous et al., 2016). It might be the case that cognitive resources attending to race and sex, as well as the detailed information provided in the applications, distracts participants from less eye-catching cues (such as attractiveness) when forming decisions about job candidates. In other words, when other (more) important information about a candidate is available, less emphasis is given to attractiveness.

A particularly interesting finding of the study was that participants (White women) tended to rate Black candidates as stronger and were more likely to invite Black candidates for interview (with small effect sizes). This finding is inconsistent with field-based research that shows ethnic minority candidates need to send around 50% more applications to be invited for interview (Zschirnt & Ruedin, 2016), and could be attributed to increased awareness of the moral and social disapproval held towards discrimination on the basis of appearance (Hurley-Hanson & Giannantonio, 2006). The nature of laboratory-based studies is that they have less ecological validity and participants might feel compelled to respond in a socially desirable manner when being monitored, particularly when dealing with areas of stigma such as race. Thus, the tendency to favor Black candidates in the current study might simply reflect social desirability effects informed by knowledge of the systemic inequalities in the Black–White employment gap (Miller, 2019). This effect might even be enhanced by the demographic of the study sample (young, White, university educated women). An alternative explanation is that participants might devalue within-race candidates more so than other-race candidates for norm violations. For example, a nonsmiling photograph or gray t-shirt (used in images in the vignettes) might be considered a norm violation, and in-group (same-race) members are more prone to devaluation (Mendoza et al., 2014).

The current study provides support for H2 that participants (White women) would favor attractive White candidates over less attractive White candidates, but not discriminate between more attractive and less attractive Black candidates. This was supported for likelihood to invite for interview but not perceived candidate strength. Findings therefore differ from Marshall et al. (1998) who found no race moderation effect, and lend support to those of Agthe et al. (2016) who found an attractiveness bias (for opposite-sex candidates) emerges for same-race targets but not for other-race targets. This moderation effect is thought to occur because (1) same-race candidates are more likely to be seen as potential mates or romantic rivals, or (2) because other-race candidates are perceived as less relevant for appearance-based social comparison because they appear to be less similar to the evaluator (Agthe et al., 2016). That the current study did not support H3 (a tendency to favor attractive male candidates over less attractive male candidates [and less attractive female candidates over more attractive female candidates] for White candidates but not Black candidates) might indirectly favor the latter explanation (other-race candidates are perceived as less relevant for appearance-based social comparison because they appear to be less similar to the evaluator) given the absence of a sex moderation contribution to the race-attractiveness moderation effect.

For the full sample, there was no main effect for candidate sex on perceived strength or likelihood to interview. However, when analyses were run exclusively on women who identified as heterosexual there was preference to favor female candidates over male candidates for interview. A further interaction effect demonstrated that this effect was more likely in the case of weaker job applications than stronger job applications. That women were more likely to favor women for interview might reflect awareness of sex inequalities in the workplace and a moral obligation to reduce discrimination. It might also reflect the nature of the job application itself with “marketing assistant” perhaps being considered a more “female-type” role. This might help to explain why the effect emerged for heterosexual women only. Gender-schema theory (Bem, 1981) contends that heterosexual women tend to favor traditional sex-type roles, and therefore (if “marketing assistant” is considered “female-type”) consider the role more suitable for a woman (see Eagly & Karau, 2002). However, nonheterosexual women often display attributes more typical of the opposite sex (Kite & Deaux, 1987) and are therefore less likely to conform to gender-type attitudes in job recruitment (Clarke & Arnold, 2018; also see Fasoli & Hegarty, 2020).

Some additional interesting findings also emerged in regard to application strength. A three-way interaction effect demonstrated that, for stronger applications only, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for men. For weaker applications, Black candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than White candidates, but only for women. This finding emerged for the full sample and subsample, and is consistent with previous research demonstrating that cognitive biases can be affected by qualification level (Espino-Pérez et al., 2018). It appears that when applications are relatively weak, Black women are favored over White women, and when applications are strong, Black men are favored over White men. This effect might reflect aspects of Gender-schema theory (gender-typed expectations of male competence at work) interacting with social desirability effects to favor Black candidates in non-field-based research. Further research is needed to identify whether these moderation effects emerge in real-world job recruitment.

There are some potential limitations that readers should consider when interpreting study findings. First, vignette research often transfers well to real-world settings (Hainmueller et al., 2015), but is susceptible to social desirability effects for hypothetical behavior. This is particularly pertinent for areas of stigma such as race, and field-based research is needed to test whether findings transfer to naturalistic settings. Second, several untested factors might also be important and warrant further investigation. For instance, the lack-of-fit model suggests that attractiveness might only be advantageous for women when applying for sex-congruent jobs, where feminine traits fit the necessary job criteria (Heilman & Caleo, 2018). This is consistent with research that has investigated attractiveness and sex in both nonmanagerial and managerial positions (Przygodzki-Lionet et al., 2010). Future research might look to investigate the moderating role of job-type when exploring sex, race, and attractiveness effects in job recruitment.

A third limitation is that the current study used single-item measures of dependent variables with unknown reliability. There is much evidence to support the utility of single-item measures in psychological science (see Allen et al., 2022), but future research should aim to test the validity and reliability of single-item measures of applicant strength and intention to interview. A fourth limitation is that the research did not include any poststudy manipulation checks, including whether some participants had suspicions about the nature of the study and adjusted their responses accordingly. A final limitation is that this study included only two ethnicities (Black/White) being rated by one ethnicity (White women). Since stereotypes surrounding Asian men and women can also affect job recruitment (Rattan et al., 2019), further research might look to explore a greater range of target races in research. Moreover, in an Australian context it might be important to explore whether Black candidates of African descent are estimated differently to Black candidates of Australian descent (aboriginal or Torres Strait islander).

5 CONCLUSION

To conclude, this study provides evidence that candidate sex, race, and attractiveness are all important in job recruitment. Findings showed that attractive/White candidates were more likely to be invited for interview than less attractive/White candidates. Participants (White women) also rated Black candidates as stronger and were more likely to invite Black candidates to interview. For analyses with nonheterosexual women removed from the sample, the data showed that female candidates were more likely to be invited to interview than male candidates. Further analyses found that when applications are weaker, Black women are favored over White women, and when applications are stronger, Black men are favored over White men. These effect sizes were all small-medium in strength (in contract to main effects for application strength that showed effects that were three to four times larger than a standard large effect size. This indicates that the strength of the application is still the primary information used to make inferences about candidates, but that sex, race, and attractiveness also play a role. These findings might be of interest to those working in job recruitment. Creating awareness of these effects might help organizations develop approaches that help to limit these effects and create a more equitable approach to job recruitment. We recommend further studies in naturalistic settings and those that target additional moderator effects such as job type to develop a clearer picture of cognitive bias in job recruitment.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.