Epilepsy and employment: A qualitative interview study with heads of human resources and occupational physicians in Austria — A call for legislative optimization according to the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan

Abstract

Objective

People with epilepsy (PWEs) often face difficulties in obtaining or keeping employment. To determine the views on this topic of the heads of human resources (HHRs) and occupational physicians (OCPs).

Method

Twelve HHRs and five OCPs underwent a telephone interview concerning the opportunities and limitations of job applications for PWEs. The interviews were performed in May 2020, in the federal state of Salzburg, Austria, and they were analyzed using the qualitative method of content analysis (Kuckartz). The legal situation was investigated according to Global target 5.2 of the Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP) on epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022–2031 by WHO.

Results

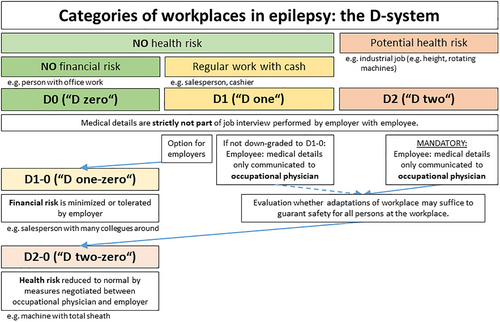

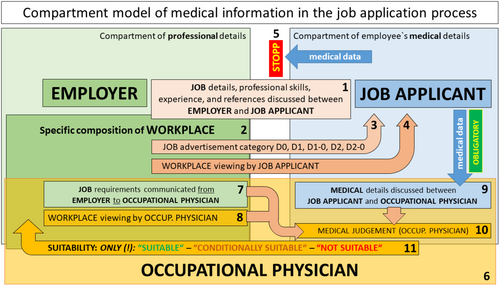

Employers were confident that employees with epilepsy could be managed well in a positive company culture and with first responders in place. The Austrian law predisposes to uncertainty among both employers and employees. In particular, it allows only retrospective juridical clarification of health-related questions in the job interview. The authors developed a classification system of workplaces, with “D0” (D-zero) meaning no health or financial danger, for example, office workers and “D1” posing still no health hazard but includes regular work with cash, for example, salespersons. “D2” means potential medical implications for the person with epilepsy or any other person at the workplace, for example, industrial worker. Measures taken to abandon the risk in D2 workplaces, for example, a total sheath for a machine, leads to reclassification as “D2-0.” With D2, OCPs evaluate the applicant's medical fitness for the job without disclosing medical details to the employer. The “compartment model of medical information in the job application process” guarantees that OCPs are the only persons who learn about the applicant's medical details.

Significance

The practical and simple classification of workplaces according to the D-system, and the concept of making medical information accessible only to OCPs may diminish stigma and discrimination in the working world for PWEs.

Video Abstract

Epilepsy and employment: A qualitative interview study with heads of human resources and occupational physicians in Austria — A call for legislative optimization according to the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan

by Leitinger et al.Key points

- Heads of human resources feel capable of employing people with epilepsy if an open-minded company culture and first responders are in place.

- However, people with epilepsy can be dismissed due to violation of Duty of Good Faith if epilepsy was not disclosed in the job interview.

- We propose a D-system that stratifies the risks at the workplace into none (D0, D zero), financial (D1), or health-related risks (D2).

- The majority of workplaces qualify as D0 or D1, where health-related questions are not appropriate and legal regulations are needed.

- We propose a “compartment model of medical information in the application process” to maximize privacy and safety in the workplace.

1 INTRODUCTION

People with epilepsy (PWEs) face substantial difficulties worldwide with obtaining or keeping their jobs.1-3 This experience was also reported by numerous patients treated in our specialized epilepsy outpatient facility. However, employment contributes substantially to quality of life in PWEs.4, 5

The number of antiseizure medications (ASMs), seizure frequency, and seizure-related interference with daily functioning were identified as relevant factors that influence the employment status.6 Employers´ attitudes were investigated by two interview studies in the late 1980s and early 1990s.7, 8 A study among 52 personnel officers or managers in the Southampton area, United Kingdom, revealed that employers´ considerations pertained mainly to safety at the workplace, liability insurance, the Employment Protection Act, and facts and figures about epilepsy.8 Employers seemed to be unaware of the employment difficulties faced by PWEs and that chances of being hired were determined mostly by line managers.7

We aimed to obtain information from interviews with heads of human resources (HHRs) and occupational physicians (OCPs) as a relevant resource for implementing improvements.

The typical role of OCPs in the application process is to examine job applicants for medical suitability for a job with potential health hazard.9 The OCPs´ professional obligations and the intervals of visitations of companies are regulated by law.9 OCPs may be employed by one usually big company or serve several smaller companies. In addition, job applicants may consult with an OCP for medical advice regarding a present or future job.

In 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) drafted an Intersectoral Global Action Plan (IGAP) on epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022–2031.10 Global target 5.2 of this IGAP addresses the difficulties regarding employment (paragraphs 150 and 153.b) and encourages countries to develop or update their legislation to promote and protect the human rights of PWEs. Becoming aware of the WHO goals when preparing this article, we investigated whether the legislation in Austria may benefit from IGAP goals.

To our knowledge, this is the first interview study with HHRs to use content analysis as a structured analytic approach, and the first interview study with OCPs.11

2 METHODS

We randomly searched for medium-size enterprises with a minimum annual turnover of 10 million Euros from a list of the 500 most successful companies in the federal state of Salzburg, Austria.12, 13 Companies of that size comprise 1.6% of all companies and engage 49% of all employees, both in the federal state of Salzburg and in Austria.14 There were no screening questions regarding familiarity with or accurate knowledge about epilepsy because PWEs also have no option to perform any such screening before applying for a job.

Due to a limited number of OCPs in the federal state of Salzburg we searched randomly for specialists in Austria. OCPs dedicated to only one company were excluded to prevent conflicts of interest.

New interview partners were recruited only as long as new arguments emerged.

The interviews were performed by telephone instead of in person due to restrictions during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in May 2020. At the beginning of the phone call, an investigator introduced himself as a neurologist working in an epilepsy center conducting a research project for the improved counseling of employers and employees when PWEs apply for a job. After obtaining verbal informed consent, we performed a semi-structured interview guided by predefined questions (Table 1), which formed the backbone of the guided interview.

Questions to heads of human resources:

|

Questions to occupational physicians:

|

However, the dialogue could lead to additional questions, whereas other questions might have been skipped. This was tolerated because the aim of the study was the qualitative inductive explorative generation of hypotheses rather than quantitative measurements. The interview was not started or was later stopped if the HHR insisted on communication in written form or suggested that the questions should be answered by the legal department as we feared that legal deapartments would provide legally correct answers not necessarily reflecting real-world conditions.

We did not collect the names of our dialogue partners and refrained from audio-taping the conversations, as we wished to generate an anonymous atmosphere in which contacted persons could talk freely about this delicate issue, similar to a previous interview study with employers.7- In addition, we refrained from inquiring about several details regarding the company to save time for the busy interview partners and to maintain the climate of privacy. The exact wording was noted by hand during the telephone call to the extent possible and was completed immediately thereafter.

Qualitative content analysis was introduced by Kracauer in 1952, with the aim of collecting latent context of text.15 It is a rule-guided codified method instead of a freely associating art of text interpretation.15 The central element is the coding card with definitions of categories of content, that is, topics with respective rules and examples to reproducibly and objectively allocate text passages to the appropriate category. A series of categories was predefined at the outset (Table S1), whereas other categories emerged during the interviews as the interviewed persons mentioned topics not anticipated (“induced” categories). The sum of all definitions, rules, and examples formed the final coding card. Following the rules of Kuckartz, the whole data material of the interviews was investigated.16

The interviews were performed in German, which is the official language in Austria. For publication, the answers of the interview partners were translated into English by a professional company (https://translated.com).

Due to the results of the content analysis, it became necessary to investigate the Austrian legal system regarding the job application process (Table S2).

3 RESULTS

In total, we interviewed 12 HHRs and five OCPs by developing and applying the respective final coding cards (Tables S3–S6). Three interviews with HHRs were not initiated and one was stopped due to direction to the company's legal department.

The content analysis revealed that HHRs did not regard epilepsy as a knock-out criterion. HHRs offered places in the office, whereas workplaces in the production line required an estimation of health-related risks. Employment of PWEs is supported by an open-minded company culture, with first responders in place and experience with seizures or chronic diseases. OCPs offer complete confidentiality regarding medical information in the case that no third party is endangered. The great competence of OCPs is their detailed knowledge about the workplaces and related steps of procedures. Together with the works-council, OCPs aim at optimizing workplaces. Both HHRs and OCPs perceived the legal situation as complex and unclear (Tables 2, S7, and S8).

Summary of HHRs:

|

Summary of OCPs:

|

As a main result, we generated the hypothesis that “the legal situation regarding the application process of PWE is unclear.” Hence, we further investigated the current legal situation in Austria to evaluate the hypothesis.

We identified four decisions of the Austrian Supreme Court (“9ObA64/87,” “9ObA46/07 s,” “RS0107830,” “RS0122551”),17-20 and highly relevant paragraphs in the Austrian Civil Code (§1157 ABGB),21 the Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act (§§ 3 and 6 ASchG),9 and the Austrian Salaried Employee's Act (§27 AngG).22 We also evaluated the contribution of the Austrian Data Protection Act23 in line with European rules (EU 2016/679),24 the Austrian Equality Act,25 and the Austrians with Disabilities Act.26 As juridical laypersons, we also contacted the Austrian Ministry of Labor directly and received a comprehensive overview of the current legal situation (Table S9). The complex interaction is summarized in Figure S1; a selection of legal problems and their potential solutions are presented in Table 3.

| Condition | Example | Potential consequence | Possible solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precontractual negotiations: the employer's “legitimate interest” | Austrian private Law (Letter from the Austrian Ministry of Labor) (Table S9) | In private law both parties may evaluate whether the other is able to fulfill its part of the contract. The employer has the right to be interested as to whether the employee's health corresponds to the level required for performance of the work. Therefore, the employer could ask about epilepsy. However, the risks associated with epilepsy vary substantially among workplaces. | The term “health” needs further specification: health should be regarded as adequate if more than 80% of work can be done; intermittent deteriorations may occur. Health-related problems should be communicated if intermittent deteriorations suggest that less than 80% of workload will be accomplished. |

| Employers' Duty of Care: employers must protect employees against health-related harm. | §1157 Austrian Civil Code,21 §§3,6 Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act9 | Employers may argue that they need health information, for example, whether the job applicant has epilepsy, to fulfill the Employers' Duty of Care. However, several workplaces do not bear a specific threat to the employee, the co-workers, or the customers, for example, office work. | The employers' Duty of Care needs to be legally linked to the intrinsic dangers of a specific workplace. The D-system provides such a system. |

| Employee's Duty of Good Faith: the employee must behave and act appropriately to remain worthy of the employer's trust. | §27 Austrian Salaried Employee's Act22; | Employees may be dismissed due to violation of the Duty of Good Faith if epilepsy was not disclosed in the job interview. | The employee's Duty of Good Faith needs to be legally linked to the intrinsic dangers of a specific workplace. The D-system provides such a system. |

| Discrimination is prohibited regarding ethnicity, conviction, religion, age, and sexual orientation | Austrian Equality Act25 | Health-related issues are not part of the anti-discrimination law. | The extension of protection against discrimination due to non-disabling diseases or disorders should be regulated by law. |

| Protection against discrimination for persons with disabilities | Austrians with Disabilities Act26 | Persons with disabilities are protected against discrimination. However, people with epilepsy often do not have disabilities, especially those who apply for regular jobs. | People with epilepsy should not be forced to apply for certificates of disability to earn protection against discrimination. |

| “Employees who are known to the employer to be particularly dangerous or likely to endanger other employees because of their health condition may not be employed in such work. This applies in particular to seizure disorders, convulsions, temporarily impaired consciousness, impairments of vision or hearing and severe depression.” | §6 (3) Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act (Employee Protection Act)9 | People with epilepsy are explicitly classified as “particularly dangerous or likely to endanger other employees.” However, a relevant danger can only be considered in connection with the concrete worksteps at a particular workplace. Without any further descriptions or legal rules, employers are forced by law to ask for epilepsy in the job interview. | Option 1 is adding explanatory information, for example, “The concrete worksteps at a particular workplace need to be considered.” Option 2 is the obligatory referral to an OCP in case that absolute medical fitness is essential or where worksteps or workplaces pose potential threats to employees. |

| If job applicants perceive a health-related question as inappropriate, they may file a lawsuit. | Letter from the Austrian Ministry of Labor (Table S9) | Filing a lawsuit is expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, the limited resources of PWEs may make them refrain from claiming their rights. | After counseling all stakeholders, a well-prepared legal regulation should come into practice. |

In short, five main legal rights were identified. First, according to the statement of the Austrian Ministry of Labor (Table S9), a work contract falls under private law as each party offers its personal services and therefore each party may inquire whether the other party can fulfill its part of the contract, including medical information. Second, the employer's Duty of Care requires the protection of all employees concerning health and personal integrity at the workplace (§1157 ABGB, §§3,6 ASchG).9, 21 Third, employees with “seizure disorders, convulsions, [or] temporarily impaired consciousness” were considered “particularly dangerous or likely to endanger other employees” and may therefore not be employed (§6(3) ASchG, Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act).9 Fourth, employees may be dismissed due to violation of employee's Duty of Good Faith, for example, if epilepsy was not disclosed earlier (Table S9) (§27 AngG).22 Fifth, the Austrian Ministry of Labor informed about the right to file a lawsuit to clarify health-related questions post hoc in each individual case (Table S9).

As a response to the legal shortcomings, the authors propose two concepts for discussion between all stakeholders to clarify the situation. First, we developed a classification system of all workplaces (D-system, D denotes danger) consisting of three major categories (Figure 1). The category “D0” (“D zero”) includes workplaces without any health or financial danger, for example, office workers. Category “D1” poses still no health hazard but includes regular work with cash, for example, salespersons or cashiers. With D1, employers may minimize or tolerate the financial risk, for example, when there are many salespersons at the cash registers; then this working place can be reclassified as “D1-0.” “D2” denotes potential medical implications for the person with epilepsy or any other person at the workplace, for example, industrial worker. In category D2 the examination by an OCP is mandatory; all medical details potentially relevant to work must be disclosed to the OCP. If all dangers can be eliminated due to advice of the OCP, for example, a machine is equipped with a full sheath, then this workplace can be reclassified as “D2-0” (“D two-zero”).

In category D2, medical information is highly relevant. This classified information must remain undisclosed to the employer. However, the OCPs include these data in their decision of whether an applicant is suitable for a particular job (“compartment model of medical information in the job application process, CMI”) (Figure 2).

4 DISCUSSION

This qualitative interview study with HHRs and OCPs revealed factors that potentially influence the application process of people with epilepsy. Because both employers and employees reported uncertainty regarding legal regulations, we performed a meticulous investigation of the legal situation. Two concepts were developed to overcome potential legal shortcomings: (1) the D-system for a swift and simple risk stratification and communication of health risks at the work place, and (2) the compartment model of medical information regulating the flow of medical information during the process of job application.

In this hypothesis-generating approach, HHRs regarded workplaces in the office or administration as safe. A borderland situation was working with cash. In contrast, in the case of potential medical hazards, HHRs refused to employ PWEs. This is in line with a study among 200 large national organizations in 1992 by the British Epilepsy Association, which revealed that employers in general had a good understanding of epilepsy and were reluctant to employ PWEs only in potentially dangerous jobs.27 However, this study was not anonymous and could have concealed negative attitudes.27 In our study, it was a positive sign that PWEs were not excluded in general; in particular epilepsy was not a knockout criterion. The HHRs even named substantial supporting factors for hiring PWEs, for example, a positive company culture and first responders who deal with emergencies of any kind at the various workplaces. Another factor was experience with epileptic seizures and chronic diseases. However, it was much less clear how to adequately determine the risk of PWEs in the workplace, in particular according to the legal framework that should prevent discrimination on the one hand and determine health-related risks in the workplace on the other hand.

The OCPs reported about their approach to provide complete confidentiality as long as third parties were not at risk. The communication to the employer was restricted to “suitable,” “conditionally suitable,” or “non-suitable” job applicant. By no means did the medical judgment communicated to the employer include medical reasoning or medical diagnoses. The huge contribution of OCPs is their very detailed knowledge of the local workplaces and their worksteps. Ideally, an employee and an OCP together meticulously searched for risks in each step of procedure. The OCPs recommended inclusion of the works-council to support accommodations of the workplace in case of conditional suitability. In general, OCPs distributed medical knowledge within the company. In the OCPs´ view, the legal situation was complex with respect to finding the balance between prevention of discrimination and warranted protection.

The typical situation in Austria is that even epileptologists cannot advise PWEs adequately to achieve both legal certainty and protection of PWEs’ interests of concealing medical details. We identified several critical aspects in the Austrian legal system that might contribute to discrimination (Table 3). In particular, the WHO aims to address legal shortcomings in the Global target 5.2 of IGAP 2022–2031.10 Employment contracts are part of private law and the exploration of whether employees can fulfill their part of the contract is a legitimate interest; that is, this includes medical questions. The Duty of Care requires employers to prevent any harm to employees. However, employers are experts in their businesses but less in medical issues, for which reason this legal principle can be involuntarily overemphasized, for example, by stating that a particular workplace was simply too dangerous, even before objective classification by an OCP. Moreover, the Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act explicitly warns about potential risks regarding PWEs (§6 (3) ASchG).9 The employee's Duty of Good Faith demands trustful behavior from the outset. By not disclosing epilepsy during the job interview, this trust may be breached, which is an established reason for the immediate dismissal of the employee (Table S9).22 The employee is in a situation of choosing between Scylla and Charybdis. Disclosure of epilepsy at the outset frequently leads to early drop out of the job application, whereas non-disclosure may lead to immediate dismissal at any time after being hired. The latter might cause a permanent psychological burden of stress. The fear of unintended disclosure due to seizures at the workplace may accompany PWEs through their entire career.28 The Austrian Ministry of Labor stated that PWEs may file a lawsuit to clarify post hoc whether a health-related question was legitimate or not. However, lawsuits consume time and financial and emotional resources, and many PWEs cannot afford them. Employers need not provide reasons for not hiring in other countries such as Australia, which makes juridical attempts even more difficult.29 We obtained independent and comprehensive expertise from an Austrian University, Faculty of Law, Business and Economics, Department of Labour Law and Business Law on the right to ask questions regarding health data during the recruitment process in Austria which was provided by a co-author (L.O.) in the peer review process (Table S10). “In conclusion, there is no universally applicable rule regarding the right to ask about epilepsy during recruitment. Instead, it must be evaluated based on a balancing of interests. Should a job offer be withdrawn, or the employment relationship terminated due to non-disclosure, a court would determine whether the question was permissible and whether truthful disclosure was necessary.” (Table S10.)

In Germany, the very low number of lawsuits contribute only little to case law.30 The Austrian law system is “primarily statutory”; that is, based on laws as opposed to customary law or judge-made law.31 However, compromises between lobbies may keep a law opaque and delegate the task of clarification to the courts.31 Consequently, the emphasis on a post hoc juridical clarification prevents any reasonable counseling of both employers and employees.

Of note, the Austrians with Disability Act requires the presence of disability, which in Austria is defined as a physical, mental, or psychological compromised function, or disturbance of the sensory functions that may complicate the participation in work life for more than 6 months. However, PWEs should not be forced to apply for a certificate as a disabled person just for obtaining protection, as this could enhance felt stigma. PWEs may or may not present with a disability, whereas the diagnosis of epilepsy may itself become a disability as it can lead to reduced psychological performance and barriers in social life.7, 32 Decreased fears of discrimination at the workplace was among the most important factors for employment.1 Of interest, the Austrian Equality Act provides protection regarding ethnicity, conviction, religion, age, and sexual orientation, but not regarding health issues. The Austrian Data Protection Act is in line with the regulation by the European Union (EU) 2016/679, which protects only against undue collection of data.24

Our suggestion to overcome this suboptimal and complex situation is a system that clarifies that the risk in pure office work is the same as with any other social event (level D0 in the D-system) (Figure 1). The work with cash without any health-related risk (D1) can be addressed or accepted by the employer (D1-0); for example, because there are always several employees in the cash desk area or an automated cash desk is mostly operated by the customers like in many supermarkets nowadays. Essentially, the employee's epilepsy requires to be addressed in workplaces with potential health-related risk (D2). However, this should be done by seeking advice from an OCP without any medical information reaching the employer (Figure 2; Compartment model of medical information). Workplaces can be made safe; for example, by installing a full sheath around a machine with rotating parts so that any kind of seizure could occur without any consequences (D2-0). The pathway would work such that all people applying for a D2 job would have to see an OCP to be evaluated for suitability for the job, but none for a D2-0 job. Of note, the D-system with five different stages (D0, D1, D1-0, D2, D2-0) is simple and swift for classification and communication, for example, in job advertisements or job interviews. It is important to emphasize that the D-system supports—but by no means replaces—counseling of job applicants by their treating physicians. In an optimized approach, the treating physicians communicate the semiology, frequency, triggers, and circadian rhythms of the seizures to the OCP who can then—with knowledge of the steps of the working procedure—competently judge the job applicant's or employee's suitability. The D-system can be easily implemented together with pre-existing frameworks used for counseling.33

Referring to the estimated data provided by the United States Census Bureau(R) for 2021, the civilian employed population age of 16 years and older was 156.4 million in total, comprising 66.0 million persons occupied in management, business, science, and arts; 25.1 million persons in service occupations; and 31.3 million in sales and office occupations, altogether 78% in estimated categories D0, D1, or D1-0.34 The 13.7 million working persons in the fields of natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations and the 20.5 million in production, transportation, and material moving occupations were considered to be category D2, or much rarer D2-0.34 Comparable numbers are in the same order of magnitude in Austria, with 71% for estimated D0, D1, or D1-0.34 These high numbers of people without a health risk at the workplace warrant a tailored legislation. The high percentages in D0, D1, D1-0, and D2-0 workplaces also mean that there will be no relevantly increased demand for OCPs. However, in the current situation, any job category may include a mixture of different risk groups referring to the D-system, expecting D0 even in the groups of natural resources and production.34, 35 Of interest, the D-system seems to work not only for epilepsy but also for several other diseases. Therefore we encourage the national statistics institutes to introduce the D-system to collect relevant information about health-related risks across the professional groups for counseling legislative authorities, interest groups, and neurologists.

As a second measure we recommend that the flow of medical information be legally regulated during the application process by using a dedicated compartment model (Figure 2). However, the compartment model of medical information does not preclude that some PWEs may voluntarily disclose their epilepsy to other staff members or the employer. The advantage of the new system would be that PWEs would not be forced to do so by legal threats. Recently, scientific work provided insight into disclosing epilepsy in the private context.36 Assertive impression management tactics was reported to be a successful disclosure strategy in job interviews.37 Further research is needed on how to best disclose epilepsy during job application, if PWEs wish to do so. The phenomenon of denying oneself career opportunities has already been elaborated in a large interview study with adult PWEs in the 1970s.38 Apart from immediate disadvantages, there seems to be a substantial discriminatory component.38- The argument that first aid in case of a seizure can only be given to PWE if the employee´s epilepsy was disclosed to all co-workers beforehand is not valid as (1) there are official broadly skilled first-responders in place and (2) all staff members can take first-aid courses to manage all different kinds of emergencies, epileptic seizures being just one among many.

We suggest a short amendment to the Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act. For example, we recommend the implementation of the D-system and the compartment model of medical information into legal regulations as §4a Austrian Occupational Health and Safety Act to clarify the situation on a rationale basis and to enable counseling with legal certainty. This study provides hints that this scheme would be supported by employers and employees alike. In many instances, service groups specialized on counseling PWEs at their workplace together with the informed works-council and the employer may proceed with their highly appreciated work without any interference by the D-system nor the compartment model of medical information at the workplace. In particular, non-profit-organizations may provide highly valuable mentoring.39-41

In U.S. companies with 15 or more employees, the Americans with Disability Act (ADA)42 refers to the US CODE “TITLE 42– The Public Health and Welfare, Subchapter I–Employment.”43 In “§12112. Discrimination, (d) Medical Examinations and Inquiries, (2) Preemployment, (A) Prohibited Examination or Inquiry,” an entity covered by this law should not “make inquiries of a job applicant as to whether such applicant is an individual with a disability or as to the nature or severity of such disability.”42, 43 The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) explained the aim of the ADA to separate the job application into a first stage before a conditional offer is made by the employer (pre-offer stage) in which only professional skills, experience, and references were evaluated whereas health-related questions were forbidden.44 After a conditional offer of employment has been made to a job applicant and before the starting of the duties (post-offer, preemployment stage), medical inquiries are allowed under a series of conditions, for example, the medical information is kept confidential.42, 43(www.adata.org, US ministry of health). Lawful post-offer health-related questions must be answered honestly; otherwise employers may refuse to hire job applicants or dismiss employees.45 Job applicants may file a complaint if they feel the question was inadequate.45

For comparison, in Brazil, PWEs who do not disclose their epilepsy may fulfill “ideological falsehood crime” referring to article 299 of Brazilian Penal Code.46 In Italy, workers do not need to disclose their diseases to the employer (Decree of July 15th 1986, article 6).47 However, for certain positions, a medical examination before hiring is required.48 A medical officer will establish if the patient is suitable for the job; the worker should disclose the disease to the medical officer. If a relevant disease is concealed, especially when it may impact the ability to perform the job, it could constitute reasons for termination for just cause.

In Estonia, each working contract starts with a probatory phase for a maximum of 4 months, during which all involved persons can evaluate the new employee regarding appropriateness.49 Employers have the right to explore whether the employee's health and other characteristics will be adequate for the work position as stated in the §6 Estonian Employment Contracts Act.49 Although this arrangement may benefit PWEs to prove their ability to work in the new position, it may also be disadvantageous as during a probationary period the termination of an employment contract is simplified and the occurrence of even one seizure at the workplace may warrant dismissal by the employer.

The definition of “health” in the context of employment should be specified. Health could be evaluated as adequate if, for example, at least 80% of the workload will be performed but interruptions in continuity may occur. PWEs in many cases do not know when a seizure will occur but looking back at the seizure history of the previous months may enable PWEs to determine for sure that the reduction of workload will be less than 20%. Such a definition may allow job applicants to honestly tell employers that their health is adequate for the job. Irrespective of this, dangers at the workplace could be dealt with by using the D-system.

A few HHRs reported that they could not offer a job to PWEs due to the small size of their companies. This correlation was also observed in previous studies in which up to 25% of interviewed personal officers would not hire PWEs.8, 50

In the current study, one HHR mentioned the extent of sick leaves as a relevant parameter. However, PWEs do not have relevant sick leaves referring to the Austrian Report of Sick Leaves 2020 by the Austrian Institute of Economic Research reporting on the pre-COVID year 2019.51 According to this report, diseases of the nervous system comprised only 2.0% of all days with sick leave compared to 21.3% of diseases of the musculoskeletal system, 20.3% of diseases of the respiratory system, and 16.3% of injuries or intoxications.51 This was also reported by staff officers in an interview study in Southampton in the late 1980s.8

John & McLellan recommended that employers should be taught medical facts about epilepsy,8 which in the current study was also recommended for other parts of the company, for example, the work council, and the general public, for example, as part of TV series (Table S4).

This study has limitations such as the small sample size. However, in this hypothesis-generating approach huge numbers are less important than in quantitative research. Despite Austria being a very small country with only about 9 million inhabitants, similar legal frameworks could be in place also in other countries. The COVID-19 pandemic might have influenced the answers obtained in the interviews. Indeed, one HHR reported that the pandemic led to a stronger agreement to protect risk groups within the company. This study also has several advantages. We directly asked involved professions, that is, HHRs and OCPs, in an anonymous way, what the limitations for PWEs could be. We used qualitative content analysis as an established scientific approach to work up the interviews and reproducibly and reliably extract information. Furthermore, we put the data into the current legal context by investigation and by involving the Austrian Ministry of Labor. We discovered several potential sources of discrimination and suggested solutions, which also contribute to Global target 5.2 of IGAP 2022–2031.10

In summary, this qualitative research based on interviews with HHRs and OCPs revealed important influential factors on the success of job applications by people with epilepsy. Most importantly, shortcomings in legislation regarding disclosure of epilepsy during the job interview need to be overcome to prevent discrimination. We propose a classification of workplaces that is suitable in particular for epilepsy but probably also for several other diseases. For this, we seek cooperation with interest groups and physicians of patients with other diseases. To our knowledge, no similar concept has been published so to date.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the nurses and technicians of the dedicated outpatient facility, the electroencephalography (EEG) lab, and the epilepsy monitoring unit for outstandingly taking care of our patients with epilepsy. We highly appreciate the friendly, swift, and competent support provided by Statistics Austria, a governmental statistics institution.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

E.T. reports personal fees from EVER Pharma, Marinus, Arvelle, Angelini, Argenx, Medtronic, Biocodex Bial-Portela & Cª, NewBridge, GL Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, LivaNova, Eisai, Epilog, UCB, Biogen, Sanofi, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Actavis. His institution received grants from Biogen, UCB Pharma, Eisai, Red Bull, Merck, Bayer, the European Union, FWF Osterreichischer Fond zur Wissenschaftsforderung, Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung, and Jubiläumsfond der Österreichischen Nationalbank, none of them related to the study.A.T. reports personal fees from the European Union and FWF Österreichischer Fond zur Wissenschafsförderung, none of them related to the study. J.H. reports speaker honoraria from LivaNova, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Angelini Pharma, none of them related to the study.Gu.K. received travel support from UCB, Eisai, and Cyberonics before 2018. She received speaker's honoraria from Eisai in 2018. None of this support was related to the study. M.L., C.K., L.O., K.O., P.T.D., M.A., F.R., Gi.K., M.M., K.N.P., B.C.P., P.V.B., J.T., T.K., and F.S. report no conflicts of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.