From trials to clinical practice: Temporal trends in the coverage of specialized allied health services for Parkinson's disease

Abstract

Background and purpose

To determine how the coverage of specialized allied health services for patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) has developed in the Netherlands since the publication of trials that demonstrated cost-effectiveness.

Methods

We used healthcare expenditure-based data on all insured individuals in the Netherlands to determine the annual proportion of patients with PD who received either specialized or generic allied health services (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech–language therapy) in 2 calendar years separated by a 5-year interval (2012 and 2017). Specialized allied health services were delivered through the ParkinsonNet approach, which encompassed professional training and concentration of care among specifically trained professionals.

Results

Between 2012 and 2017, there was an increase in the number of patients with any physiotherapy (from 17,843 [62% of all patients with PD that year] to 22,282 [68%]), speech–language therapy (from 2171 [8%] to 3378 [10%]), and occupational therapy (from 2813 [10%] to 5939 [18%]). Among therapy-requiring patients, the percentage who were treated by a specialized therapist rose substantially for physiotherapy (from 36% in 2012 to 62% in 2017; χ2 = 2460.2; p < 0.001), speech–language therapy (from 59% to 85%; χ2 = 445.4; p < 0.001), and occupational therapy (from 61% to 77%; χ2 = 231.6; p < 0.001). By contrast, the number of patients with generic therapists did not change meaningfully. By 2017, specialized care delivery had extended to regions that had been poorly covered in 2012, essentially achieving nationwide coverage.

Conclusions

Following the publication of positive trials, specialized allied healthcare delivery was successfully scaled for patients with PD in the Netherlands, potentially serving as a template for other healthcare innovations for patients with PD elsewhere.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) currently affects over 6 million individuals worldwide, posing an enormous burden on patients, relatives, and caregivers [1]. During the last 3 decades, the global burden of PD has more than doubled, in large part as a result of increasing numbers of older people, although environmental factors may contribute as well [1]. In the absence of preventive modalities for PD, the social and economic burden caused by PD is expected to rise further in the coming decades [2]. Against this background, there is an urgent need to widely implement treatment modalities that have been proven to be effective for patients with PD.

Recent years witnessed large gains in the nonpharmacological treatment of PD. In particular, several studies demonstrated that specialized care delivery of physiotherapy [3], occupational therapy [4], and speech–language therapy [5] can lead to fewer complications and to a better quality of life for patients with PD. The Dutch ParkinsonNet is an innovative model of integrated care that entails specialized care delivery across each of these disciplines [6, 7]. To be considered specialized, allied therapists participating in ParkinsonNet must complete extensive and repeated training programs, comply with an annual performance review, and treat a minimum number of five patients with PD each year. Clinical studies suggest that since the introduction of this care model in the Netherlands in 2004, patients with PD sustain fewer disease complications and experience an improvement in self-perceived performance in daily activities, and healthcare costs have decreased [3, 4, 8, 9]. These findings suggest that the future burden of PD at the population level could be reduced if delivery of such cost-effective specialized care could be implemented on a broader scale. However, it generally remains challenging to translate clinical trial findings into a sustainable implementation within everyday clinical practice.

Here, we investigate temporal trends between 2012 and 2017 in the coverage of specialized allied healthcare to patients with PD in the Netherlands, delivered through the ParkinsonNet approach, as a potential template for scaling of care delivery for patients with PD or other chronic conditions elsewhere.

METHODS

Data source

We retrospectively analyzed a database of health insurance claims (Vektis) that contains the healthcare expenditures of all insured individuals in the Netherlands, which is 99% of all Dutch residents (±17 million people). We used data from Vektis between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2017, as data on the number of patients with PD receiving specialized care before 2012 were incomplete for occupational therapy and speech–language therapy. We could not use data after 2017 because these data had not been fully processed when we conducted the current study.

We extracted data on community-based physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech–language therapy. Of note, this analysis does not include data on therapies provided in the setting of hospitals or nursing homes. We used diagnostic codes obtained from medical records of all neurological departments in the Netherlands to identify patients with PD (Diagnosis Related Group code 501). We considered patients with PD who were referred to an allied health therapist to be therapy-requiring patients. Allocation to specialized or usual care allied health therapy was based on the choices of patients and referring physicians. We did not have access to diagnostic codes of patients who were treated exclusively by physicians other than neurologists (e.g., family physicians, geriatricians), but this involves only a very small minority of Dutch patients with PD. In the 2012 health insurance claims database, regional data were categorized into 66 regions of the Netherlands with a similar number of allied health professionals. Because of an increase in the number of allied health professionals between 2012 and 2017, some regions were split into smaller subregions. As a result, there were 70 regions in the 2017 database. We extracted data on the total population of the Netherlands in 2012 and 2017 from Statistics Netherlands (Central Agency for Statistics; www.cbs.nl).

We have made summary data on the use of community-based physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech–language therapy in patients with PD publicly available at: https://www.parkinsonatlas.nl/.

Specialized care delivery: ParkinsonNet

We defined specialized care deliverers as therapists who participated in ParkinsonNet. The remaining therapists, here referred to as generic therapists, provided patients receiving usual care and did not receive any of the components of the ParkinsonNet intervention. Detailed methods of the ParkinsonNet intervention have been published previously [10, 11], and are summarized in Box 1. In short, key elements include the specific training of therapists, structuring of the referral process (to increase the number of patients with PD seen by specialized therapists), and optimization of communication between the participating health professionals. To qualify for ParkinsonNet participation, therapists had to complete a basic 3-day training program, attend follow-up regional interdisciplinary meetings (three times per year), attend the ParkinsonNet conference (once biannually), complete annual standardized questionnaires on the quality of care they provided, and treat a minimum of five patients with PD each year. After the initial introduction of ParkinsonNet, it remained possible for additional therapists who previously lacked PD-specific training to join the network, provided they could fulfil the requirements for ParkinsonNet alliance as outlined above.

Box 1. Key components of the ParkinsonNet approach during the study period

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| guidelines* |

|

| Preferred referral |

|

| Education |

|

| Information technology platform |

|

| Selection |

|

| Commitment |

|

| Transparency about quality of services and health outcomes |

|

| Patient-centered approach |

|

- * Evidence-based recommendations and consensus-based statements (www.parkinsonnet.nl/parkinson/behandelrichtlijnen)

Statistical analysis

We determined the number of patients with PD who received specialized or generic therapy across three disciplines (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech–language therapy) between 2012 and 2017, both at a nationwide and regional level. In the main analysis, we compared the nationwide proportion of patients receiving specialized care for the calendar years 2012 and 2017 for each discipline, using χ2 statistics. For each discipline, we also compared the proportion of regions in which at least half (>50%) of patients who required therapy were treated by a specialized therapist in the years 2012 and 2017. In addition, we assessed the mean ratio of patients with PD per therapist for the years 2012 and 2017 separately for specialized and for generic therapists who treated at least one PD patient.

We had some missing data on the level of PD-specific expertise of therapists in 2012, specifically for physiotherapy (13.4%), speech–language therapy (12.7%), and occupational therapy (7.5%). In 2017, missing data for each discipline were <0.3%. In the main analysis, we only used complete data (i.e., in each year we excluded patients whose therapist's level of PD-specific expertise was unknown). Furthermore, we had missing regional data on speech–language therapy for four regions in 2012; all other regional data were complete. To assess to what extent differentially missing data may have affected our observations, we performed separate sensitivity analyses in which we repeated the main analysis after modeling all therapists with an unknown level of PD-specific expertise: (i) in 2012 as specialized therapists and in 2017 as generic; or (ii) in 2017 as specialized therapists and in 2012 as generic. We also conducted sensitivity analyses on the change in ratio of patients per therapist using the same assumptions.

RESULTS

Number of patients with PD

In 2012, the claims database contained 28,913 patients with PD, for a total population in the Netherlands of 16,730,000, indicating a crude prevalence of PD of 1.8 per 1000 individuals. By 2017, the number of patients with PD had risen to 33,382, for a total population of 17,082,000, indicating an unadjusted prevalence of PD of 2.0 per 1000 individuals. This corresponded with a 10% rise in the unadjusted prevalence of PD over the study period.

Number of therapists stratified by level of PD care expertise

In 2012, there was a total of 25,217 physiotherapists, 3076 speech–language therapists, and 1373 occupational therapists. By 2017, there were 27,643 physiotherapists (+10% compared to 2012), 3975 speech–language therapists (+29%), and 2090 occupational therapists (+52%). The number of specialized physiotherapists rose distinctly over the study period (711 in 2012 to 1238 in 2017; +74%), as did the number of specialized occupational therapists (247 to 402; +63%) and specialized speech–language therapists (221 to 377; +71%).

Number of patients with PD with therapy stratified by level of PD-specific expertise

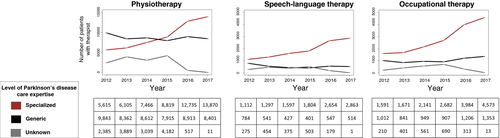

The numbers of patients with PD with physiotherapy, speech–language therapy, and occupational therapy, stratified by level of PD-specific expertise, are shown in Figure 1 for each year between 2012 and 2017. Between 2012 and 2017, the number of patients with PD with any physiotherapist rose from 17,843 in 2012 (62% of all patients with PD that year) to 22,282 (68%) in 2017. That rise was due exclusively to an increase in the number of patients with PD treated by a specialized physiotherapist, whereas the number of patients with PD treated by a generic physiotherapist or a physiotherapist with an unknown level of PD expertise declined (Figure 1). The percentage of physiotherapy-requiring patients treated by a specialized physiotherapist rose from 36% in 2012 to 62% in 2017 (+26%; χ2 = 2460.2; p < 0.001).

The number of patients with any speech–language therapist rose from 2171 in 2012 (8% of all patients with PD that year) to 3378 in 2017 (10%). That rise was exclusively due to an increase in the number of patients with PD treated by a specialized speech–language therapist, whereas the number of patients with PD treated by a generic speech–language therapist or a speech–language therapist with an unknown level of PD expertise declined (Figure 1). The percentage of patients requiring speech–language therapy treated by a specialized speech–language therapist rose from 59% in 2012 to 85% in 2017 (+26%; χ2 = 445.4; p < 0.001).

The number of patients with any occupational therapist rose from 2813 in 2012 (10% of all patients with PD that year) to 5939 in 2017 (18%). That rise was largely due to an increase in the number of patients with PD treated by a specialized occupational therapist. The number of patients with PD treated by a generic occupational therapist also increased, albeit less distinctly, whereas the number of patients with PD treated by a generic occupational therapist with an unknown level of PD expertise declined (Figure 1). The percentage of patients requiring occupational therapy treated by a specialized occupational therapist rose from 61% in 2012 to 77% in 2017 (+16%; χ2 = 231.6; p < 0.001).

In sensitivity analyses, our observations remained robust under several different assumptions on the level of PD-specific expertise of therapists of whom that level was unknown (Supplementary Material 1).

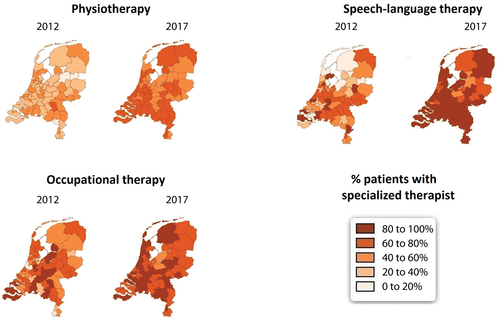

Regional distribution of specialized care delivery

Nationwide claims data were categorized into 66 regions of the Netherlands in 2012, whereas data were categorized into 70 regions in 2017. In 2012, in only 5 (8%) of 66 regions were the majority of physiotherapy-requiring patients with PD treated by a specialized physiotherapist. By 2017, the majority of physiotherapy-requiring patients with PD was treated by a specialized physiotherapist in 63 (90%) of 70 regions. The number and percentage of regions in which the majority of therapy-requiring patients with PD were treated by a specialized speech–language therapist (45 [73%] to 68 [97%]) and occupational therapist (49 [74%] to 68 [97%]) also rose substantially. In Figure 2, the regional distribution of therapy-requiring patients with PD with a specialized therapist in 2012 and in 2017 is further specified.

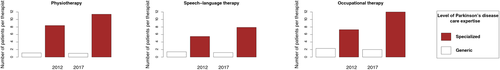

Ratio of patients per therapist

As illustrated in Figure 3, the mean ratio of patients per generic physiotherapist was very low and even declined somewhat throughout the study period (1.1 in 2012 and 1.0 in 2017, corresponding with a 9% decline). The mean ratio of patients per generic speech–language therapist (1.4 in 2012 and 1.2 in 2017; −19%) and generic occupational therapist (2.3 in 2012 and 2.0 in 2017; −16%) was also very low and declined further. By contrast, the mean ratio of patients per specialized physiotherapist (8.4 in 2012 and 11.4 in 2017; +35%), specialized speech–language therapist (5.5 in 2012 and 7.9 in 2017; +42%) and specialized occupational therapist (7.3 in 2012 and 12.0 in 2017; +65%) increased substantially throughout the study period.

In sensitivity analyses, the increase in ratio of patients per specialized speech–language therapist and ratio of patients per occupational therapist remained robust under several different assumptions on the level of PD care expertise of therapists of whom that level was unknown (Supplementary Material 2). For generic occupational therapists, the ratio of patients per therapist would have declined in each scenario. For the ratio of patients per specialized physiotherapist, generic physiotherapist, or generic speech–language therapist the direction of change would have varied under different assumptions.

DISCUSSION

Through implementation of the ParkinsonNet approach, coverage of cost-effective community-based specialized care delivery to patients with PD in the Netherlands improved considerably between 2012 and 2017. Furthermore, during this study period, we observed a substantial growth in the number and proportion of patients per specialized therapist, suggesting a greater concentration of PD care among specialized providers. Clinical trials had shown that specialized therapists achieve better outcomes than generically trained therapists, partially because of their greater case load [3, 4, 8, 9]. As the volume shifts described here took place after completion of these clinical trials, it is conceivable that the long-term effectiveness of specialized care delivery may be even larger than previously estimated. Taken together, we believe that this successful expansion of a cost-effective care approach to a nationwide scale might serve as an example to improve care elsewhere, not only for PD but also for other chronic conditions.

Before further interpreting the results, we will address several limitations of this study. First, because PD case detection depended on diagnostic codes of neurological clinics, we could not include patients who never visited any hospital or who during the 6-year study period were treated exclusively by other specialists (e.g., geriatricians). Patients who never visited a hospital are generally more care-evasive, and specialized community-based care may not have reached these patients. However, this subgroup is likely small, as the prevalence of PD in this study (2 per 1000 individuals) was similar to the prevalence of PD in population-based studies with in-person examinations [12]. Second, we had no access to data on allied health interventions delivered in hospitals or nursing homes. Third, because PD case detection depended on diagnostic codes, we probably included some patients who actually had a form of atypical parkinsonism. However, it is unlikely that this misclassification differentially affected specialized or generic allied health therapy. Fourth, the level of PD-specific expertise was unknown for some therapists, especially during the first few years of follow-up. We performed several sensitivity analyses to assess to what extent our observations would have been different in several hypothetical scenarios with respect to the level of PD-specific expertise of those therapists. For each scenario, the rise in number of patients treated by a specialized therapist between 2012 and 2017 remained robust across each discipline. Despite these limitations, a unique strength of this study was that we could leverage nationwide data on the use of community-based physiotherapy, speech–language therapy, and occupational therapy over a 6-year period, allowing us to rigorously assess temporal trends in the coverage of specialized care delivery on an unprecedented scale.

In the 2012 to 2017 interval, several other interventions raised greater awareness of the benefits of specialized care among people with PD as well as among healthcare professionals, ranging from virtual house calls to patient-centered education on management of daily life issues [13, 14]. A distinguishing feature of the ParkinsonNet intervention was the focus on specialized training and empowerment of allied health therapists who work in the community. Importantly, in this study, we observed a stark contrast in temporal trends between allied health professionals who received specific training through the ParkinsonNet approach and those who did not. Although the number of patients receiving care by allied health professionals participating in ParkinsonNet increased substantially between 2012 and 2017, the number of patients seen by the other nonparticipating allied health professionals did not change meaningfully. Furthermore, the case load per therapist only increased for allied health professionals participating in the ParkinsonNet intervention, and the proportion of regions in which allied health therapy was predominantly delivered by professionals participating in the ParkinsonNet intervention rose substantially during the study period. These findings make it unlikely that the changes in referral patterns could be explained by generic trends toward greater information provision in the Netherlands. We previously demonstrated that healthcare costs are lower in ParkinsonNet clusters compared with usual-care clusters [3]. We also showed that specialized physiotherapy as delivered through ParkinsonNet is associated with fewer PD-related complications in real-world practice [9], and that occupational therapy improves self-perceived performance in daily activities by patients with PD [4], with lower costs for caregivers [8]. However, it remained unclear to what extent such specialized care delivery, as demonstrated in clinical trials, could subsequently be extended into a sustainable implementation within everyday clinical practice. Here, we observed that the number of patients with PD with any form of physiotherapy, speech–language therapy, or occupational therapy increased substantially between 2012 and 2017. These increases could not be explained by an increase in unadjusted prevalence of PD during the study period (10% in 6 years), and hence more likely reflects the growing recognition that optimal management of PD requires a multidisciplinary approach [15, 16]. For physiotherapy and speech–language therapy, the increase was exclusively due to a growth in the number of patients treated by a specialized therapist, whereas the number of patients with a generic therapist declined. For occupational therapy, the number of patients increased for both specialized and generic therapists, but the increase was far more distinct for specialized therapists.

The number of community-based specialized therapists increased substantially during the study period, due to the nationwide ParkinsonNet training programs. Furthermore, when looking at regional distribution of specialized care delivery, we observed that the proportion of patients receiving specialized therapists in regions that were previously poorly covered increased substantially during the study period. In fact, the percentage of regions in which the majority of physiotherapy-requiring patients were treated by a specialized physiotherapist rose from 8% in 2012 to 90% in 2017, whereas specialized speech–language therapy and occupational therapy was provided to the majority of therapy-requiring patients in almost all (97%) regions by 2017. The successful implementation of the ParkinsonNet intervention was likely driven by several factors [17]. First, the ParkinsonNet intervention was experienced as a welcome intervention by the participating allied health professionals, who now felt more empowered to treat this complex neurological condition, and also by the patients, who now were able to obtain ready access to highly specialized professionals who understood the intricacies of their condition. An important success factor was the development of guidelines, which, in the absence of more convincing scientific evidence in the early days of the network implementation, were initially largely determined by practice-based evidence. These guidelines served as educational materials for the baseline training of all participating professionals, helped to reduce unwanted variations in care between professionals, and served as a basis for the intervention arm in subsequent randomized clinical trials that were performed to gather further evidence. These trials were a further important success factor, as it helped to provide a robust evidence base that demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of the network approach. Another crucial determinant was the commitment of the neurologists and PD nurse specialists to preferentially refer patients to the specialized allied health therapists working in the community, allowing them to now substantially increase their caseload and thereby redeem the time investment of their baseline training. The supporting Information technology backbone also helped with the successful limitation of ParkinsonNet in various ways. The web-based healthcare finder further facilitated the referral process and concentration of care among the trained experts, whereas the use of web-based communities allowed for easy communication about complex cases and new research findings. The fact that education did not stop after the baseline training program was also felt to be helpful: all participating professionals meet three times a year during regional events and meet at least once every 2 years during a national congress, which serves both to educate and inspire the participants. However, implementation of the network also met with a number of challenges. Perhaps the greatest difficulty was the disappointment among healthcare professionals who were not allowed to enter the network, because inclusion of too many participants would conflict with the ParkinsonNet aim to concentrate care among a limited number of highly trained professionals. As demonstrated here, nonparticipants experienced a gradual reduction in number of persons with PD in their practices, which by some was experienced as a loss of their professional joy. The second major challenge related to the financial reimbursement of this innovative healthcare approach. Just like a hospital or another type of institutionalized care, networks require a certain amount of overhead, for example, to oversee the training programs, to updated guidelines, and to maintain the information technology backbone. The insurance companies initially found it difficult to identify the proper means to reimburse the network overhead, because their systems were traditionally aimed at funding institutions rather than integrated networks. This latter challenge has meanwhile been overcome in the Netherlands, where the insurance companies now collectively reimburse the overhead of the nationwide ParkinsonNet network, which clearly outweighs the net cost savings that are achieved annually [18].

Taken together, the success factors outweighed the challenges—most of these have meanwhile been overcome—and this likely explains why implementation of the ParkinsonNet approach was successfully introduced at a nationwide scale as a cost-effective intervention in the Netherlands [3, 4]. In a broader context, it is noteworthy that the ParkinsonNet approach, which was developed in the public insurance-based healthcare system of the Netherlands, has recently been successfully introduced in healthcare systems that have a different infrastructure (e.g., Kaiser Permanente, an accountable care organization in California) [19]. Future studies are warranted to assess whether wide-scale coverage of specialized allied health services can also be achieved in those healthcare systems, as well as its possible implications for cost savings.

In conclusion, coverage of cost-effective specialized care delivery to patients with PD in the Netherlands improved considerably between 2012 and 2017 following implementation of the ParkinsonNet approach. The successful implementation of this specialized care approach on a nationwide scale can serve as a template to improve care for patients with PD or other chronic conditions elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There were no sponsors for this specific work. The Centre of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders was supported by an excellence grant of the Parkinson's Foundation. The authors declare no funding sources related to this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. B.R.B. currently serves as Associate Editor for the Journal of Parkinson's Disease; serves on the editorial of Practical Neurology and Digital Biomarkers; has received honoraria from serving on the scientific advisory board for Abbvie, Biogen, UCB, and Walk with Path; has received fees for speaking at conferences from AbbVie, Zambon, Roche, GE Healthcare, and Bial; and has received research support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, the Michael J Fox Foundation, UCB, Abbvie, the Stichting Parkinson Fonds, the Hersenstichting Nederland, the Parkinson's Foundation, Verily Life Sciences, Horizon 2020, the Topsector Life Sciences and Health, and the Parkinson Vereniging. S.K.L.D. was supported in part by a Parkinson’s Foundation - Postdoctoral Fellowship (PF-FBS-2026).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K.L.D.: conception and design of the work, analysis, drafting the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published. M.E.: analysis, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. M.S.G. and M.M.: interpretation of data for the work, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. B.R.B.: conception and design of the work, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. S.K.L.D. is the guarantor of this work.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

No ethical approval or informed consent was required given the nature of this study, which involved analyses of anonymous medical claims data. As part of the standard health insurance policy, all patients included in the claims database had agreed to their data being used anonymously for analyses.

STATEMENT OF INDEPENDENCE

The researchers were independent from funders.

PATIENT AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

Patient or public involvement was not feasible given the nature of this study, which involved analyses of anonymous medical claims data.

TRANSPARENCY DECLARATION

S.K.L.D. (the manuscript's guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The summary statistics on anonymous medical claims data used in the analyses will be made available to other researchers upon reasonable requests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

We have made the data that support the findings of this study publicly available at: https://www.parkinsonatlas.nl/.