Attendance at pre-pregnancy care clinics for women with type 1 diabetes: A scoping review

Abstract

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus occurs in one in every 275 pregnancies and can result in increased morbidity and mortality for both mother and baby. Several pregnancy complications can be reduced or prevented by attendance at pre-pregnancy care (PPC). Despite this, less than 40% of pregnant women with pre-gestational diabetes receive formal PPC. The aim of this scoping review is to identify the barriers to PPC attendance among women with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review by searching five databases (Ebsco, Embase, Ovid and PubMed for literature and the ProQuest for any grey/unpublished literature) for studies in English between 2000 and 2022. Studies that evaluated attendance at PPC for women with type 1 diabetes were included.

Results

There are multiple barriers to PPC attendance, and many of these barriers have been unchanged since the 1990s. Identified barriers can be grouped under patient-centered and clinician-centered headings. Patient factors include knowledge and awareness, unplanned pregnancies, negative perceptions of healthcare and communication issues, unclear attendance pathways and logistical issues including time off work and childcare. Clinician factors include physician knowledge, time constraints and lack of comfort discussing pregnancy/contraception.

Conclusion

This review highlights the ongoing problem of poor attendance at PPC and identifies key barriers to be addressed when developing and implementing PPC programs for women with type 1 diabetes.

What's new?

- Pre-pregnancy care (PPC) reduces mortality and morbidity for women with diabetes; however, only 32% of pregnant women with pregestational diabetes attended PPC.

- Our scoping review identified 31 studies on the topic of PPC attendance.

- Several barriers were identified and can be grouped into patient and clinician factors. Patient factors include knowledge and awareness, unplanned pregnancies, negative perceptions of healthcare, unclear attendance pathways and logistical issues including time off work and childcare. Clinician factors include physician knowledge, time constraints, lack of comfort discussing pregnancy/contraception and communication deficits.

- These data will inform future work designing PPC programs that are acceptable, relevant, and accessible to all individuals with type 1 diabetes who are planning pregnancy.

1 INTRODUCTION

An estimated 1% of all pregnancies are affected by type 1 diabetes and many women face significant complications during their pregnancies including pre-eclampsia, macrosomia, pre-maturity and stillbirth.1-3 Outcomes for women with diabetes are frequently worse than those without diabetes and based on this inequality the writers of the 1989 St Vincent's Declaration formulated a 5-year plan to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes for women with diabetes.4

The provision of pre-pregnancy care (PPC) is key to preventing many of these life-long consequences, which place a significant financial burden on the health service.5

The goal of PPC is to identify and address lifestyle, medical, social and behavioral issues to optimize health and positively impact on the subsequent pregnancy outcome. PPC attempts to ensure that individuals are advised about potential risks and can make an informed decision about becoming pregnant if specific factors are not modifiable.6 Furthermore, PPC is cost-effective and reduces many complications of pregnancy.7

When delivered in the context of type 1 diabetes, PPC facilitates improved glycaemic control by targeting a haemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) below 6.5% (48 mmol/mol), thus providing an optimal environment for the developing fetus. PPC also works alongside other interventions like continuous glucose monitoring and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusions which have been shown to improve the metabolic profile of early pregnancy.8

Many studies have reported on the associations between poor glycaemic control in early pregnancy and adverse outcomes for both mother and baby. It is understood that hyperglycemia leads to overproduction of reactive oxygen species and this in turn can cause oxidative stress which affects embryonic development and organogenesis.9

There are also many teratogenic drugs used to treat long-term complications of diabetes, which can cause congenital anomalies.10 PPC aims to improve glycemic control and ensure that all drugs used to control long-term complications are safe in pregnancy. This will ensure an optimal environment for the conception and development of a healthy pregnancy and prevent the devastating feelings of grief and stress experienced by mothers following the diagnosis of a fetal anomaly.11, 12

PPC also provides the opportunity for screening for the unrecognized complications of diabetes. For example, retinopathy may be present in more than 40% of women of child-bearing age.13 Many of these complications can progress during pregnancy if not monitored closely and promptly treated. Clinicians should also use this opportunity to discuss lifestyle factors like immunization, smoking and folic acid use.

PPC is recognized as an essential component of the holistic care of a mother with diabetes, the benefits of which can be seen long term for both mother and baby. Although the benefits of PPC have been shown to outweigh the cost of running these clinics, PPC is still very poorly attended and rates of 26%–32% have been reported.14, 15

The aim of this scoping review is to identify studies that have evaluated PPC attendance and non-attendance in women with type 1 diabetes and to identify barriers to attendance. We will present potential solutions to these barriers in our discussion.

2 METHODS

2.1 Literature search

Following best practice for performing scoping reviews, five electronic databases were searched for relevant literature as follows: CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Embase, OVID and PubMed for published literature and ProQuest for grey/unpublished literature.16 Keywords included in the search were “diabetes”, “type 1”, “preconception”, “prepregnancy”, “attendance” and “non-attendance”. Search words were combined using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”. Truncation was used for different word endings.17

A sample search strategy for the Embase database is demonstrated in Table 1.

| #1 Diabet* OR type 1 diabet* = 1 493 981 |

| #2 Preconception OR pre-conception = 8164 |

| #3 Prepregnancy OR pre-pregnancy = 58 151 |

| #4 Attendance = 45 858 |

| #5 Nonattendance OR non-attendance = 2483 |

| #6 2 OR 3 = 64 479 |

| #7 4 OR 5 = 46 080 |

| #8 6 AND 7 AND 1 = 97 |

Research articles, guidelines and reviews were included in the search. Only articles published in English were included.

We excluded studies published before 2000; studies that did not include type 1 diabetes and studies evaluating the benefits of PPC without examining the reasons for non-attendance. We included studies that evaluated clinician or patient perspective of PPC and included studies that evaluated women with T1DM and type 2 diabetes as one group.

Reference lists of pertinent articles were searched manually, and relevant papers were added to the search. One author had written many relevant studies in the search list and was contacted by mail and gave a list of relevant references. These articles were manually searched and those not already discovered were added to the search. All articles were stored on EndNote

The search was conducted from November 2021 until August 2022.

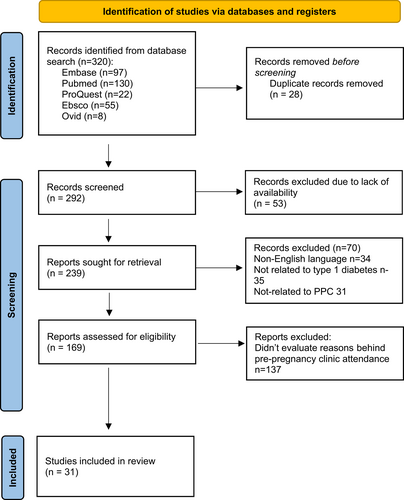

The results of this scoping review were presented in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.

There is no published protocol available for this scoping review.

2.2 Study selection

One reviewer (PF) completed the search for studies. These articles were saved to Endnote. Duplicates were removed, and all citations were transferred to RAYYAN (a free, web-based screening tool). RAYYAN allows users to indicate whether the article is for inclusion or exclusion and give reasons for this decision.

Titles and abstracts were blindly reviewed by two separate reviewers (RL and PF). Following the initial search, the blind was removed from RAYYAN. Both reviewers could then see decisions made by each other. Any disagreement over article relevance was resolved through discussion.

2.3 Data extraction

Data were extracted on author, date of publication, country, study design, participants, and sampling, aims, outcomes and limitations. These data were then entered into a pre-designed template (see Table 1). We used word mapping to identify common themes or patterns from the relevant studies and grouped them into categories.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Search results

A total of 320 records were identified (Figure 1). Twenty-eight duplicates were removed, and 53 records were excluded before screening due to a lack of access. A total of 231 records were available for screening. On the first round of screening, 70 records were excluded (four were not in English, 35 were not related to type 1 diabetes and 31 were not related to preconception or pre-pregnancy). A further 137 records were excluded as they did not evaluate pre-pregnancy clinic attendance, leaving 31 articles for full-text review.

3.2 Study characteristics

We identified five semi-structured interviews; four cross-sectional studies; nine surveys; three questionnaires; two mixed-method studies; two prospective studies; two retrospective cohort studies; one randomized control trial; one collective case study; one extended case method and one audit.

Eight studies originated from the United Kingdom; five studies were American; five studies were Australian; three were from China; two were from Spain and one from Canada; one Chilean, one French, one Irish, one Italian, one Saudi Arabian and one Maltese study were also identified. Details of all included studies can be found in table 2.

| No | Author | Country | Study design | Participants and sampling | Aim | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Zhou30 2018 |

China | Mixed methods | 178 women with type 1 diabetes who were pregnant or planning pregnancy | To assess awareness of pre-pregnancy clinic in women with type 1 diabetes of childbearing age |

|

Poster presentation |

| 2 |

Zheng22 2018 |

China | Cross-sectional study | 435 women of childbearing age with type 1 diabetes | To investigate if the awareness of pre-pregnancy clinic in women with type 1 diabetes |

|

Small area in China |

| 3 |

Zhu19 2012 |

Western Australia | Prospective study | 51 women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes who attended antenatal care over 6 months. | To investigate the level of awareness of availability of PPC -investigate willingness to attend PPC investigate barriers to access |

|

Small study one hospital short time frame |

| 4 |

Wang47 2017 |

Canada | Audit of attendance and patient survey | 150 patients with type 1 diabetes | To identify reasons for nonattendance at clinics and reduce this number by characterizing nonattendance patterns |

|

Only one hospital was included |

| 5 | King44 2009 | Australia | Collective case study | 7 women with type 1 diabetes | To identify women's experience about pregnancy and birth |

|

|

| 6 |

Shaw45 2008 |

UK | Extended case method | review 1683 records; 177 women with type 1 diabetes given questionnaire; 32 semi-structured interviews with women with diabetes | To gain knowledge about factors that affect women's decision to plan pregnancy |

|

|

| 7 |

Sereika37 2017 |

UK | Quantitative self-reported retrospective and prospective surveys | 102 women with type 1 diabetes | To compare pregnancy planning behaviors of women who received information about preparing for pregnancy while they were teenagers 8to those who did not receive this information |

|

Small study in one area |

| 8 |

Sapiano29 2012 |

Malta | Interventional follow-up prospective study | 37 women with type 1 diabetes at age 12 to 30 years | To assess the level of knowledge and awareness related to PPC |

|

|

| 9 |

Magdelano52 2018 |

USA | Survey | 97 of 577 surveys were included in women between 18 and 35 years old with type 1 and type 2 diabetes |

|

|

Small amounts of surveys returned |

| 10 |

Murphy35 2010 |

UK | Semi-structured interviews and qualitative research | 29 pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes | To explore views of women who did not attend PPC prior to pregnancy |

|

Small sample size small area |

| 11 |

Khon34 2018 |

USA | Survey and pilot of intervention | 29 healthcare providers; 50 adolescent girls with type 1 diabetes |

|

|

|

| 12 |

Jeraiby20 2021 |

Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study | 187 women of childbearing age with type 1 diabetes | Assess awareness of PPC among women with type 1 diabetes and their self management status |

|

Single center study |

| 13 |

Glinianaia23 2014 |

UK |

Survey Multiple logistic regression |

2293 pregnancies in women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes over 15 years | To investigate trends and indications of preparation for pregnancy by women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and explore their predictors |

|

Large study over long time span |

| 14 |

Griffiths46 2008 |

UK | Semi-structured interview | 15 women with type 1 diabetes 20–30 weeks pregnant | To explore women's accounts of their journey to becoming pregnant with type 1 diabetes |

|

|

| 15 |

Grady27 2016 |

USA | Self-reported survey | 147 nulligravid women with type 1 diabetes recruited online | To examine how women understand their ability to experience a healthy pregnancy and reduce their risk of adverse outcomes |

|

|

| 16 |

Giraudo48 2021 |

Chile | Quantitative research questionnaires | 109 women with type 1 diabetes and 362 women without diabetes aged 12–25 years. Parents signed consent for those <18 | To evaluate risky behaviors including unprotected sexual intercourse, sources of information and knowledge related to reproductive health in comparison with those without diabetes |

|

|

| 17 |

Fischl38 2010 |

USA | Randomized control trial | 88 teens with type 1 diabetes | To evaluate the impact of PPC program for teens with type 1 diabetes |

|

|

| 18 |

Ennack25 2016 |

Morocco | Survey | 33 young adults with type 1 diabetes |

|

|

|

| 19 |

Charron-Prochownik26 2006 |

USA | Interviews | 80 adolescents | To explore awareness of issues related to diabetes in pregnancy, PPC and contraception |

|

|

| 20 | Earle28 2017 | UK | Mixed methods, systematic review and quantitative interview |

Two primary sites and 11 secondary site 12 interviews with women with diabetes and 18 qualitative studies |

To identify facilitators and barriers to uptake of PPC |

|

|

| 21 | Carrasco-Falcon31 2018 | Spain | Cross-sectional descriptive observational study | 50 women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes | To identify the associated factors and barriers related to involvement of these women in PPC |

|

|

| 22 |

DPSG32 2005 |

France | Multicenter cross-sectional study | 138 women with type 1 diabetes |

|

|

Reasons for poor attendance was not investigated in this study |

| 23 |

O'Higgins33 2013 |

Ireland | Semi-structured interview | Women with type 1 and tyoe 2 diabetes who are pregnant or of child bearing age |

|

|

|

| 24 |

Morrison18 2018 |

Australia | Cross-sectional survey | 429 women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes |

|

|

|

| 25 | Hendrieckx21 2021 | Australia | Survey | 526 women with T1DM and 103 women with type 2 diabetes | To assess differences in knowledge and beliefs about pregnancy in women with diabetes |

|

|

| 26 | Komiti24 2013 | Australia |

The Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and Theory of Reasoned Action |

123 women with T1DM and T2DM |

To further our understanding of the factors-associated PPC uptake |

|

|

| 27 | Mortagy50 2010 | UK | Qualitative cross-sectional study | 18 GPs involved in delivering care to women with pre-gestational diabetes |

Explore the perspective of GPs and secondary care health professionals on the role of GPs in delivering preconception care to women with diabetes. |

|

|

| 28 | Bolla51 2013 | Italy | Anonymous online questionnaire | 395 healthcare professionals | Document training and knowledge on diabetes and pregnancy among diabetes professionals |

|

|

| 29 | Magdelano49 2020 | Spain | Retrospective cohort study | 577 women with diabetes |

|

|

|

| 30 | Zhou30 2018 | China | Retrospective review | 178 women with T1DM |

Assess the awareness of preconception counselling in childbearing age women with T1DM |

|

|

| 31 | McCorry36 2012 | UK | Semi-structured interviews | 14 non-pregnant women with T1DM |

Explore the attitudes about pregnancy and preconception care seeking in a group of nonpregnant women with |

|

|

- Abbreviations: DPSG, diabetes in the pregnancy study group; PPC, pre-pregnancy care.

3.3 Findings

There are many barriers and facilitators discussed within all the studies; however, several recurring factors were identified, and these will be discussed in depth.

3.3.1 Patient-centered findings

The demographic of participants who attended PPC was analyzed in most of the studies listed below. In general, women attending PPC were older than those who did not, were less likely to have children already, had higher levels of education, were more likely to be married and had better glycaemic control than those who did not.18-24

Knowledge

The striking recurring theme within all the studies was the lack of awareness about the need for or availability of PPC.18, 19, 22, 25-31 In one study, none of the participants reported receiving information on pregnancy preparation25; and in another study, no patient was offered PPC, and more than 50% had never heard the term preconception counselling.26 While lack of awareness of PPC was very common, rates approached 85% in other studies.32

Other barriers included patients not being aware of the need for PPC or the potential complications of diabetes in pregnancy.20, 25, 28, 31-35 Over 25% of women surveyed reported no complications associated with pregnancy in diabetes.31 Nearly 40% of women thought they could not get pregnant and one-third knew the importance of retinal screening in pregnancy20 and almost half did not know the risk of congenital anomaly in diabetes.32 Another study identified that women were keen to receive details information about pregnancy, but experienced anxiety around potential complications.36 Follow-up studies of women who received PPC as teenagers found higher rates of PPC and planned pregnancies in adulthood compared with women who did not and found fewer barriers to PPC, demonstrating the importance of PPC at every stage.37, 38

Unplanned pregnancies

Unplanned pregnancies occur in as many as 16.2% of pregnancies.39 This percentage is much higher in women with diabetes. In one study, 41% of pregnancies were unplanned40 and rates as high as 45.1%–47% have been reported.18, 19 Unplanned pregnancies were a common reason for not attending PPC.18, 19, 21, 31

In the general population, risk factors for unplanned pregnancies include the use of illicit drugs and alcohol; wanting to be accepted by peer groups; lack of knowledge about contraception and sexual abuse.41

For women with diabetes risk factors for unplanned pregnancies are having type 2 diabetes, lower levels of education, smoking, lower self-reported quality of life, negative relationships with healthcare providers, previous unplanned pregnancies and being involved in unhappy relationships. Women with unplanned pregnancies are also younger and less likely to be married.21, 40

Women with T1DM and unplanned pregnancies have a higher HbA1C entering pregnancy19 and represent a high-risk obstetric group with high rates of neonatal hypoglycaemic and neonatal care.42, 43

Despite the frequency of unplanned pregnancies, the majority of HCPs are reluctant to initiate the conversation on contraception and will only do it if the parent or the patient enquires about contraception or on finding on the patient is sexually active.34

Negative perception of healthcare and communication issues

Many studies also evaluated women's perspectives of healthcare interactions and their diabetes control.18, 19, 31, 35 A small percentage of the women interviewed in one study felt they knew enough about the diabetes to manage it well before pregnancy and did not consider it necessary.18, 19, 31 Others felt that attending PPC would be an intrusion, over-medicalize their pregnancy, make their pregnancy different to women without diabetes and some described their interactions as depressing.18, 35, 44, 45

Studies explored the theme of negative patient–clinician interactions acting as a deterrent to discussing pregnancy.18, 27, 29, 33, 35, 46 In particular feelings of self-blame were associated with reduced attendance and poor outcomes.27 In one study, more than 20% of women reported a negative relationship with their healthcare provider.35 Other women felt fear was a strong deterrent from attending and clinicians should focus on the positive aspects of pregnancy.33 Other studies stressed the importance of avoiding blame or judgement.29, 47 For participants who are actively thinking about pregnancy and contraception, the conversation can be difficult to initiate.18

To combat these barriers HCPs need to come up with new and innovative ways to assist and encourage women with diabetes to plan pregnancies and attend PPC, and patients should be empowered to access and request referrals at a time and through a medium that suits them.38

Unclear attendance pathways and practical issues

Lastly, practical issues such as clear referral pathways and logistical issues were also reviewed. Four studies evaluated how patients attend PPC.19, 28, 29, 48 Endocrinologists, obstetricians and general practitioners were all common routes of referrals; however, women were occasionally uncertain about how best to access care. Studies found that 49% of referrals came from general practice; however, only 16% of those referred attended their appointment indicating sub-optimal communication between GP and the patient.19

Other studies found that 29% of women attending PPC were referred by their GPs, 57% by their endocrinologist and 14% through other sources.

Other logistical and practical factors identified were time restraints caused by childcare, work commitments, distance to clinic and forgetting appointments.18, 28, 33, 34, 47 Many also felt that greater education of family and friends would lead to much social support.33

3.3.2 Clinician-centered findings

Clinician factors include physician knowledge, time constraints, lack of comfort discussing pregnancy/contraception and communication deficits.

Physician knowledge

A study performed by Magdaleno et al.49 found that many professionals believe they are providing far more PPC than they actually are. It was found that only 18.9% of women reported having been informed about or received PPC whereas HPCs felt they had informed all women. Similarly Kohn et al. found that 30% of healthcare providers have had never discussed pregnancy and 40% had never discussed contraception with women with diabetes.34 Many GPs report being unsure of their role in providing PPC50 and not all endocrinologists have received formal training in diabetes and pregnancy.51 This is particularly evident as not all clinicians are willing to prescribe contraception to women with diabetes and sub-optimal control.51

From a patient perspective, patients feel that their GPs and practice nurses need to be more aware and more involved in the provision of care.33, 44

Time constraints and lack of comfort

Primary care providers often report time constraints, feelings of discomfort regarding sexual health discussions and difficulty in initiating the conversation as barriers to discussing contraception.34, 49, 50, 52 Others feel that while reproductive health is important, 21% of healthcare providers feel that other aspects of diabetes care should take precedence.34

4 DISCUSSION

A large body of evidence demonstrates benefits from PPC for women with diabetes, their offspring and the health service; however, attendance rates continue to be below 50%.7, 15 The broad geographical range from which studies originate does demonstrate that this is a global problem, however with only 24 relevant articles identified, it is clear that the prevention of diabetes-related complications through PPC is an under-studied area. It is also disappointing to see that many of these issues, which were identified as far back as 1996 still have not been resolved.40, 53 This scoping review identified many of the reasons why PPC attendance is so low, and many ways in which small changes could make a significant difference to overcome this problem. These issues can be categorized under patient-centered and clinician-centered headings. Patient factors include knowledge and awareness, unplanned pregnancies, negative perceptions of healthcare and communication issues, unclear attendance pathways and logistical issues including time off work and childcare. Clinician factors include physician knowledge, time constraints and lack of comfort discussing pregnancy/contraception.

The first big change that can be made is ensuring that education regarding pregnancy complications begins at puberty for all girls with diabetes. Women and teenage girls should know that a pre-pregnancy service is available and how they can access this service. This knowledge imparted to young women can then be used in later life and have major health benefits for decisions made in adulthood.54 Sereika et al. demonstrated that women who are given information about PPC as an adolescent are more likely to use effective birth control and look for guidance from a HCP when planning a pregnancy.37 A deterrent to providing contraception advice to adolescents may be a perceived feeling of awkwardness in initiating the conversation; however, this needs to be overcome to deliver high standards of healthcare delivery.34

All the studies reviewed demonstrated the lack of knowledge regarding the need for PPC and that many women fail to realize the potential complexity of diabetes and pregnancy.

Studies have highlighted the issue of time limitations during consultations to raise the issue of birth control and pre-conceptual counseling. Lack of knowledge within primary healthcare teams has also been displayed.

To improve attendance in this area clinicians should focus on improved communication.35 Service planners and managers need to be made aware of these issues and consider the benefits of providing finance and education to HCPs so that their knowledge can be updated and maintained. It is vital that there is no conflicting information given to women as this can lead to lack of trust, a reluctance to engage in the future and increased levels of fear and self-protection in doctors.55

A number of studies also evaluated the prevention of unplanned pregnancies. Recommendations are made within many studies to commence education about contraception and PPC at puberty and continue throughout childbearing age as unplanned pregnancies are not simply confined to the teens and early twenties.23, 29, 35, 37, 48 Despite the frequency of unplanned pregnancies, HCPs are reluctant to hold this conversation. The frequency of unplanned pregnancies highlights the need for new and innovative ways to improve how young women get access to this important information regarding contraception and allow them to make an informed decision about attending these vital clinics.28

It is also important that attendance at pre-pregnancy clinic does not disrupt the woman's day-to-day life. Clinics that run during office hours are not always suitable for women to attend. Work and childcare commitments make attendance at these clinics very difficult, and many women do not want to take time off work or let their employers know they are planning pregnancy. The provision of clinics with the professional highly qualified in diabetes and pregnancy, at a time that suits most women, would prove beneficial and cost-effective when balanced against the potential complications of an unplanned pregnancy. Primary care, and community-based PPC have been successful in women with type two diabetes.56 Digital healthcare education initiatives have been successful and well received in other areas of maternal health,57 and young, especially computer-literate women appreciate digital educational resources.58

Relationships with HCPs are also crucial. Poor attendance is known to be a major problem in people with diabetes worldwide.59 As much of diabetes management relies on effective self management guilt can become part of daily living when participants feel they have not met the expected targets.60 Participants feel that constant correction becomes a routine part of their consult with HCP and relationships can become very difficult. Archer et al. explain that pointing out a patient's failings and poor control is a trigger for guilt and shame60 which leads to non-attendance. Failure to attend routine diabetes and endocrine clinics may lead to a decline in health, a lack of valuable knowledge and re-attendance can be very difficult to establish.59 Holistic treatment of diabetes requires the treatment of the person as much as the disease; however, the importance of this can be lost in the busy clinic environment.61 While improving relationships can take a long time and require ongoing effort, the introduction of a new and qualified HCP can improve patient care. Nurse-led education is often positively viewed by participants and the identification of a key worker or supporter for a patient with diabetes who helps patients engage with the healthcare system is being evaluated in young adults with type 1 diabetes.62, 63 Employment of additional staff would also ease the burden of under-staffing, which is widely recognized as a barrier to effective diabetes care and reduce the over-reliance on non-specialists, which often typifies diabetes care.64, 65

This study has a number of strengths. We used a robust methodology to identify all relevant studies and provide a comprehensive and detailed review of the current literature. The limitations of this study include the exclusion of studies published in languages other than English and the exclusion of women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Type 2 diabetes now accounts for between one third to half of the pregnancies in women with diabetes.3, 66 Our review demonstrates that women with type 2 diabetes were less likely to get PPC than those with T1DM.18, 21 Women with type 2 diabetes face particular challenges in their pregnancies including older age and higher BMIs on entering pregnancies and slightly higher rates of neonatal deaths compared with women with type 1 diabetes (1.1% vs. 0.7%, p = 0.013).66 These adverse events happen despite better blood glucose control on entering pregnancy; however, the higher rates of smoking, teratogenic medication use and hypertension at conception indicated that this group stands to benefit significantly from PPC. Future studies should aim to address the barriers to PPC attendance in this cohort.

5 CONCLUSION

Despite the clear benefits for both mother and infant, PPC remains poorly attended among women with type 1 diabetes. This scoping review categorises and provides a comprehensive summary of the identified barriers to attendance at PPC in this population. These data provide a framework on which to develop PPC programs that are effective and accessed by a majority of women with type 1 diabetes (Table 2).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pauline Ferry, AEM and Fidelma P. Dunne contributed to the original idea and design of the study. Pauline Ferry, Catherine Meagher, Roisin Lennon and Christine Newman carried out the literature search and reviewed abstracts. Christine Newman and Pauline Ferry compiled results and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the final manuscript. Christine Newman is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Dr Linda Biesty, senior lecturer in midwifery at the National University of Ireland, Galway, for her conceptual guidance for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data derived from public domain resources.