Endoscopic observation of the hypopharyngeal region using a super soft hood

Abstract

Watch a video of this article.

Brief Explanation

Patients with previous upper aerodigestive tract cancer frequently develop pharyngeal cancer, and their pharynxes require careful observation during surveillance endoscopy.1 However, pharyngeal observation is technically challenging due to the pharyngeal reflex and the narrow working space. In particular, the anatomically closed space between the postcricoid area and the posterior wall of the hypopharynx sometimes causes overlook of cancers.2 Super soft hood (space adjuster; TOP, Tokyo, Japan), which is a highly flexible silicon hood, adjusts to the narrow working space, facilitating endoscopic treatment such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).3

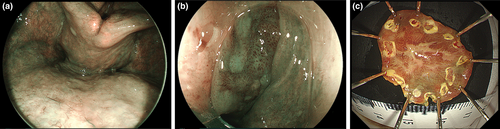

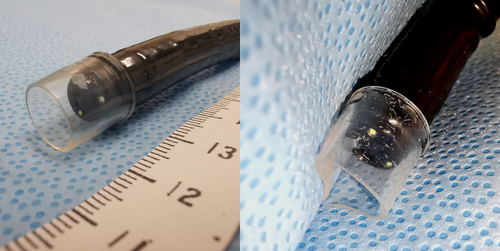

A 67-year-old man underwent transoral endoscopy with a magnifying endoscope (EG-L600ZW7; FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan) and the video endoscopic system LASEREO (FUJIFILM) for surveillance after radiation therapy for oropharyngeal cancer. Despite careful observation of the pharynx using pethidine hydrochloride4 and the Valsalva maneuver,5 the hypopharyngeal region was not adequately visualized (Fig. 1a). Therefore, a super soft hood was attached to the endoscope (Fig. 2) and the hypopharyngeal region was re-examined. To avoid injuring the post-radiation mucosa with the edge of the hood, the endoscope was first inserted into the cervical esophagus and then slowly pulled out. This enabled visualization of the hypopharyngeal mucosa both directly and through the transparent hood. On blue laser imaging, a 10-mm brownish lesion with irregular microvessels was detected in the postcricoid area (Fig. 1b) and pathologically diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma by biopsy (Video 1). ESD was performed for the lesion (Fig. 1c), and the diagnosis of the resected specimen was intraepithelial squamous cell carcinoma.

When the Valsalva maneuver does not sufficiently widen the hypopharyngeal space, use of a super soft hood may be a promising option for achieving a detailed pharyngeal examination. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, we recommend the hood for patients at high risk of developing pharyngeal cancer, not for all patients.

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Acknowledgment

We thank Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.