A systematic review on the effect of routine outcome monitoring and feedback on client outcomes in alcohol and other drug treatment

India Cordony and Llewellyn Mills contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Issues

Routine outcome monitoring (ROM) involves regularly measuring clients' outcomes during treatment, which can then be fed back to clinicians and/or clients. In the mental health field, ROM and feedback have been shown to improve client outcomes; however, no systematic reviews have examined whether improvement is also seen in alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment outcomes. This review examines whether feedback to clients and/or clinicians of ROM data in AOD treatment improves future client outcomes.

Approach

This systematic review of papers identified in Medline, PsycInfo and Scopus examines the effect on client outcomes of feeding back ROM data to clinicians and/or clients in AOD treatment settings. Key client outcomes included substance use, treatment attendance and wellbeing measures.

Key Findings

Ten studies were included—five randomised controlled trials and five pre–post within-subjects designs. Six studies were deemed good- or fair-quality. Of these six, three provided feedback to clinicians only, one to clients only, and two to both clients and clinicians. Only one of the six found feedback was associated with significant reductions in substance use and only among off-track clients. Four of the six found feedback improved other outcomes, including treatment retention, global functioning, therapeutic alliance and mood symptoms.

Conclusions

There may be some positive effects for clients of providing feedback to clients and/or clinicians; however, the small number of randomised trials and the heterogeneity of methods, outcome measures and findings, mean that firm conclusions cannot be drawn about the efficacy of feedback until larger randomised studies are conducted.

Key Points

- Routine outcome monitoring is the regular measurement of client outcomes during treatment.

- We examined whether feedback of routine outcome monitoring data to clinicians/clients in alcohol and other drug treatment improves client outcomes.

- Feedback improved at least one outcome in four out of six good- or fair-quality studies reviewed; however only one study found feedback to be associated with reduced substance use, and only among off-track clients.

- The small number of studies and heterogeneity of methods, outcomes and findings mean firm conclusions cannot be drawn about the efficacy of feedback as an intervention pending larger randomised trials.

1 INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders (SUD) are a serious problem globally, carrying devastating costs. Given the severity and magnitude of this issue, it is important that alcohol and other drug (AOD) services continue to improve treatments they provide to clients. In recent years, there has been a move towards routine outcome monitoring (ROM) as a way of assessing and improving treatment effectiveness. ROM involves regularly measuring client outcomes, often using patient reported outcome measurement tools. The collected data concerning clients' progress and treatment response can then be provided as feedback to clinicians and clients. Examples of outcome measurement tools currently used in AOD services globally include the Outcome Rating Scale [1], Session Rating Scale [2], Treatment Outcomes Profile used in the UK [3], Australian Treatment Outcomes Profile used in Australia [4] and Alcohol and Drug Outcome Measure in New Zealand [5].

Evidence from psychotherapy, counselling and mental health research suggests that routinely monitoring client outcomes and providing clinicians with this data improves clients' treatment outcomes [6-14]. Several mechanisms are proposed for how this occurs. First, ROM and feedback helps clinicians to determine the appropriateness of current treatment and identify need for further treatment [15]. It allows clinicians to see exactly which treatment aspects facilitate change, prompting clinicians to use certain treatment elements more strategically in future [16]. At the service level, program directors can evaluate which treatments need improvement and make changes. Second, monitoring allows clinicians to identify clients who are not progressing as expected or are at risk of drop-out. Without ROM and feedback, clinicians are generally poor predictors of which clients are at risk of deterioration [17]. Regular monitoring and feedback alert clinicians in the early stages when individual clients begin to deteriorate, allowing them to modify their treatment approach, employing more targeted treatment strategies and potentially improving chances of slowing or reversing the deterioration [18]. Third, feedback allows clinicians to engage in professional development. Clinicians may take deliberate action in response to feedback, such as personal reflection, identifying problem areas, seeking guidance from experts and executing a plan for improvement [19]. A study conducted among psychotherapists showed that the more clinicians engaged in professional development in response to feedback, the better their clients' outcomes were [20]. This suggests that improved outcomes after feedback may be due to clinicians' self-reflection and self-improvement. Additionally, monitoring provides supervisors with data on individual clinicians, enabling supervisors to engage underperforming clinicians in further professional development [21]. Fourth, monitoring facilitates better discussion between clinicians and clients about clients' goals and progress, leading to better client engagement and participation in treatment [22].

While there is ample evidence in the mental health field for feeding back routinely collected data to clinicians to improve client outcomes, there is limited and conflicting evidence on the effect of feeding back this data to clients. One study at a counselling centre showed that providing feedback on clients' weekly progress to both clinicians and clients did not improve clients' mental health outcomes compared to when feedback was given to clinicians only, suggesting that client feedback is less important for improving outcomes [23]. However, this result was inconsistent with findings from an earlier study, which showed that feedback to both clients and clinicians improved client outcomes significantly more than feedback to clinicians alone [24]. The authors proposed that feedback to clients may have improved the client-clinician relationship, enhanced the therapeutic process and increased client motivation, resulting in more effective therapy meetings [24]. These proposed mechanisms are largely untested and much remains unclear about whether and how client feedback may improve outcomes.

A 2012 meta-analysis examining the effect of ROM and feedback to clients and clinicians in mostly mental health care settings found that feedback had a positive impact on clients' physical and/or mental health in 63% of studies [25]. ROM and feedback also consistently improved communication between clinicians and clients, leading to more frequent and effective conversations, suggesting that improved client-clinician communication may be key to improving client outcomes.

Given its general success in mental health treatment, ROM and feedback should theoretically lead to improvements in the treatment of SUDs. Carlier and van Eeden [25] conducted a narrative review of studies examining the effects of ROM in drug and alcohol settings; however, to date there have been no systematic reviews of the evidence for whether ROM and feedback is associated with improvements for AOD treatment seekers specifically. This study aims to examine available evidence to determine whether feeding back ROM data to clients and/or clinicians improves future client outcomes in AOD treatment.

2 METHODS

2.1 Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Electronic literature searches were performed between July 2020 and November 2021. The databases Medline (via Ovid), PsycInfo (via Ovid) and Scopus were searched for articles published in English with no limitation on year of publication or study type. The search was performed using keywords combined with relevant subject headings. The following combination of search terms was used in each database: (‘feedback informed treatment’ or ‘patient level feedback’ or ‘partners for change outcome management system’ or ‘progress monitoring’ or ‘routine outcome m*’ or ‘routine monitoring’ or ‘client feedback’ or ‘patient feedback’ or ‘measurement based care’) and (‘substance use’ or ‘alcoholism’ or ‘alcohol abuse’ or ‘drug abuse’ or ‘drug addiction’ or ‘drug dependency’) and (‘treatment outcome*’ or ‘outcome*’). We manually searched the bibliographies of identified articles to ensure complete coverage. One additional paper was identified through contact with experts.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Our eligibility criteria were chosen in accordance with our PICO framework. Our PICO framework consisted of: Population—people with substance use disorders receiving treatment in AOD treatment settings; Intervention—feedback from ROM; Control—control group or condition of no feedback from ROM; and Outcome—AOD treatment outcomes. To be included in the review studies needed to: (i) be English language; (ii) be conducted primarily in AOD treatment settings with participants receiving treatment primarily for SUDs; (iii) examine the effect on client outcomes of feeding back routinely monitored data to clients and/or clinicians; (iv) have feedback from ROM as the study intervention; (v) contain a control group or condition of no feedback from ROM; and (vi) measure AOD treatment outcomes (e.g., substance use, treatment retention). Narrative reviews, systematic reviews, commentaries and research that did not examine the effect on client outcomes of feeding back routinely monitored data to clients and/or clinicians were excluded. Two rounds of screening (title/abstract and full text) were undertaken by one author (IC) using the above inclusion/exclusion criteria, in consultation with a second author (LM). After selection, all 10 included studies were reviewed by two authors (IC and LM) and six studies by three authors ([21, 26, 27] by NL and [28-30] by KM). Records were stored and managed in the software program EndNote [31].

2.3 Data extraction

One author (IC) extracted data from each study and entered it into Tables 1–3. A second author (LM) reviewed Tables 1–3, ensured the data were correct and added any additional relevant data. A third author (KM or NL) then followed the same process for the studies listed above. Data items that were extracted from each study included the author, year of publication, study population, treatment settings, outcomes measured, study design, methods, intervention, control group/condition, overall study quality and results.

| Study | Population and treatment setting | Outcomes measured | Design | Method | Intervention | Control | Overall study quality | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crits-Cristoph et al. (2010) [26] ‘A randomized controlled study of a web-based performance improvement system for substance abuse treatment providers’. |

N = 1584 clients. N = 118 clinicians. N = 20 clinics. Clients: Patients receiving group counselling sessions for substance use problems at one of the enrolled clinics. Setting: 20 outpatient substance use treatment clinics (non-methadone maintenance) in the USA, providing group counselling sessions. |

Alcohol use (days in past week) and drug use (days in past week) using modified Addiction Severity Index [35]. Therapeutic alliance scores, using client-rated Therapeutic Alliance Scale [36]. Treatment attendance rates (clinic records). Clinician measures of organisation culture (Organisational Readiness for Change) [37] and job satisfaction (Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire) [38]. |

Cluster randomised controlled trial. | Clinics randomly assigned to intervention or control group. Clients in control group completed Patient feedback survey at baseline (week 1) and end of study (week 12) and clinicians received no feedback. Clients in intervention group completed the patient feedback survey weekly for 12 weeks. Clinicians received average caseload feedback reports weekly (clinicians blinded to client ID). Team meetings held every 4 weeks to use feedback reports to stimulate discussion, review treatment strategies and set goals. | Patient feedback survey form completed by clients after each group treatment session aggregated into average caseload feedback reports and provided to counsellors. | No feedback provided. | Good | No significant difference in alcohol use, drug use, therapeutic alliance or attendance between feedback and control groups. No significant differences in clinician measures between groups. The authors concluded: ‘The overall finding of this study was that there is no evidence for the effectiveness of the PF [Patient Feedback] system’ ([26], p. 259). |

Crits-Christoph et al. (2012) [27] ‘A preliminary study of the effects of individual patient-level feedback in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs’. |

N = 304 clients. N = 38 clinicians. Clients: Aged 18 or above, seeking a new course of individual outpatient treatment for alcohol or drug use problems. Setting: 3 outpatient substance use treatment clinics (non-methadone maintenance) in the USA, providing individual counselling sessions. |

(OQ-45) [39]: assesses global function (subscales of quality of interpersonal relationships, social role functioning, symptom distress) with addition of substance use outcomes (days alcohol use in past 7-days, days drug use in past 7-days). Treatment retention (weeks in treatment). |

Before–after (pre–post) within-subjects non-randomised controlled design. | Outcomes measured 12-weeks pre-intervention (Phase I) and 12 weeks post-intervention (Phase II). OQ-45 administered prior to each counselling session. During Phase II, OQ-45 feedback immediately provided to clinicians after each weekly counselling session. Clients not progressing as expected identified as ‘off-track’ and given the Assessment for Signal Clients once, which measured therapeutic alliance, motivation, social support and stressful life events. Clinicians then also receive Assessment for Signal Clients feedback reports for off-track clients. | OQ-45 assessment completed electronically by clients provided immediately to counsellors after each treatment session. | No feedback provided. | Good | Overall no significant differences in substance use, global functioning or treatment retention between Phase I and Phase II. However, in ‘off-track’ clients, significantly greater rates of: (i) reduction in alcohol use from week 1 to 12 during Phase II period (intervention) than weeks 1 to 12 during Phase I (control) period; (ii) improvement in total OQ-45 scores and drug use from point of going off-track to week 12 of Phase II compared to rates of improvement across 12-week Phase I period. |

Miller et al. (2005) [21] ‘The partners for change outcome management system’. |

N = 160 clients. Clients: Not clearly specified. Setting: ‘New Start’—a substance use treatment service by an international employment assistance program. Specific focus on skill building and building ‘sober friendly’ support networks. |

ORS [1]; a four-item scale measuring individual functioning, interpersonal functioning, social role performance and overall wellbeing. SRS [2]; a measure of therapeutic alliance. |

Study design not adequately described in paper. | Clients completed ORS and SRS at each session and clinicians received these scores. Clinicians could graph and discuss scores with individual clients at each session or adopt a computer-based system that provides warnings when clients' outcomes fall outside ‘normal’ parameters. Other details of study design not provided by authors, including timing of feedback. | ORS and SRS assessments completed by clients and scores provided to clinicians. | The clinicians who did not seek feedback at the first sessions were treated as a control condition | Poor | Seeking feedback about therapeutic alliance (via SRS scores) was associated with significantly increased probability of success (84% of successful clients had a clinician who sought feedback in the first session vs. 63% of unsuccessful clients). No inferential statistics are provided for this assertion, nor any description of the analyses conducted. |

McCaul and Svikis (1991) [34] ‘Improving patient compliance in outpatient treatment: clinician-targeted interventions’. |

N = 6 clinicians. Clients: Not clearly specified. Setting: Not clearly specified. |

Average number of individual counselling sessions attended per month by clients. Average number of group counselling sessions attended by client. Number of breathalyser monitoring visits attended by client. Percentage of counsellors whose clients' mean participation met the minimum standards. |

Before–after (pre–post) within-subjects non-randomised controlled design. | Standards established for minimum acceptable level of client participation. Outcomes measured 4 months pre-intervention (control) and post-intervention (intervention). During intervention phase, written feedback provided monthly to clinicians on their clients' participation compared to proposed standards and prior month's participation. |

Feedback to clinicians of client participation in 3 program service components (individual counselling sessions, group counselling sessions, breathalyser visits). | No feedback provided. | Poor | Overall, client participation improved in all 3 program service components in feedback condition. Mean number of individual counselling sessions increased from 1.6 to 2.3, group counselling sessions increased from 0.7 to 1.4 and breathalyser monitoring visits increased from 6 to 6.6 post feedback. Significant improvement in mean number of individual and group counselling sessions attended in feedback condition (p < 0.05), while increase in mean number of breathalyser monitoring visits was not significant. Percentage of counsellors whose clients' mean participation levels met the minimum standards improved across all 3 program service components in feedback condition: (i) for individual counselling sessions, from 26-52%; (ii) for group counselling sessions, from 32-80%; and (iii) for breathalyser visits, from 51-80%. Non-significant improvement in individual counselling sessions (p < 0.1). Significant improvement in group counselling sessions (p < 0.05) and breathalyser visits (p < 0.01). |

Schuman et al. (2015) [41] ‘Efficacy of client feedback in group psychotherapy with soldiers referred for substance abuse treatment’. |

N = 263 clients. N = 10 clinicians. Clients: Soldiers referred by commanding officer for alcohol/drug misconduct. Setting: Army Substance Abuse Outpatient Treatment Program. |

ORS [1] scores. Patient progress report scores [41]: clinician and commanders' perceptions of client treatment outcomes. Number of treatment sessions attended. |

Between-subjects randomised controlled trial. | Clients randomly assigned to feedback or treatment as usual. Outcomes measured for five group psychotherapy sessions. Clients completed ORS before each session. Clinicians in feedback group received feedback after each session (frequency of sessions not specified) and could respond to feedback as they wished (no attempts made to manage clinician's actions after feedback). | ORS assessment completed by clients before each session and scores provided to clinicians after each session. | No feedback provided. | Good | Overall, significant improvement in all outcomes in feedback group. (i) Significantly higher post-treatment ORS scores in feedback group than control group (d = 0.28, p = 0.011). (ii) Significantly more clients achieved clinically significant improvement (gain of at least 5 points and completed treatment above the ORS cut-off score of 25) in feedback condition than control condition (28.47% compared to 15.08%, χ2 = 28.1, p < 0.001). (iii) Clinician and commanders' perceptions of client treatment outcomes was significantly higher in feedback condition (χ2 = 18.7, p < 0.001 and χ2 = 28.1, p < 0.001 respectively). (iv) Significantly higher attendance rates in feedback condition than control (average 4.16 sessions compared to 3.55, t(260) = 3.4, p < 0.01). (vi) Significantly fewer clients prematurely terminated treatment in feedback condition than control (48 compared to 62, χ2 = 5.4, p < 0.001). |

Seitz and Mee-Lee (2017) [35] ‘Feedback-informed treatment in an addiction treatment agency’. |

N = not reported. Clients: 30% mandated to attend. Other characteristics not specified. Setting: Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment in Minnesota, a community-based substance use treatment service. |

ORS [1] scores. SRS [2] scores. GSRS [42]: a measure of group therapeutic alliance. Retention rates. Effect size of treatment. |

Expert opinion. | Clients at Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment regularly completed ORS, SRS and GSRS assessments with scores provided to clinicians (frequency of feedback not specified). Feedback informed clinical supervision sessions held with clinicians and supervisors to adjust treatment plans. Control condition created by expert's knowledge of what centre was like before implementation of feedback system (pre-intervention). Timing of feedback not specified. | ORS, SRS and GSRS assessments completed by clients and feedback provided to clinicians. | No assessments or feedback provided. | Poor | Overall, authors reported that feedback improved client outcomes; however, the results were mostly anecdotal and unquantified. They report (i) increased effect size in one specific program service (Mental Health and Recovery), from negative prior to feedback-informed treatment (i.e., clients getting worse) to 0.95 after. (ii) Personal anecdotes of feedback improving client outcomes. (iii) Increased retention rates (not quantified). (iv) Higher client treatment completion rates than other drug and alcohol centres in the state (state average 76–78%, Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment average 86%). |

- Note: Effect sizes and p-values supplied as described by authors and may vary in format.

- Abbreviations: GSRS, Group Session Rating Scale; OQ-45, Outcome Questionnaire; ORS, Outcome Rating Scale; SRS, Session Rating Scale.

| Study | Population and treatment setting | Outcomes measured | Design | Method | Intervention | Control | Overall study quality | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Andersson et al. (2017) [44] ‘Interactive Voice Response with Feedback Intervention in Outpatient Treatment of Substance Use Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial’. |

N = 73 clients. Clients: Adolescents and young adults <25 years old. Setting: Maria Malmö, an outpatient substance use treatment facility for adolescents and young adults in Sweden. Run by social services and psychiatry departments. Offers individualised psychosocial treatments, plus pharmacotherapy as needed. |

Stress symptoms—AHSS [44]. Anxiety and depression symptoms—SCL-8D [45]. Total summary score of AHSS and SCL-8D. Alcohol and drug use. |

Between-subjects randomised controlled trial. | IVR computer program uses pre-programmed scripts to interact with clients via mobile phone call. Clients randomly assigned to IVR only (control) or IVR plus feedback (intervention). IVR system measured client outcomes twice weekly over 3 months via mobile phone call. Clients in intervention group received brief automated feedback at end of each call (twice weekly) on individual reported levels of stress, depression and anxiety symptoms. | Personalised feedback to clients on stress and mental health symptoms. Feedback provided compared clients' current scores to previous scores, indicating whether change was positive, negative or neutral. | No feedback on data collected from IVR system provided. | Good | Significantly greater improvement in AHSS stress scores (p = 0.019), total SCL-8D score (p = 0.037) and anxiety subscale of SCL-8D scores in feedback group than in control group (p = 0.017). No significant difference in depression subscale of SCL-8D scores or global substance use scores between feedback and control groups. |

- Note: Effect sizes and p-values supplied as described by authors and may vary in format.

- Abbreviations: AHSS, Arnetz and Hasson score; IVR, Interactive Voice Response; SCL-8D, Symptoms Checklist 8D.

| Study | Population and treatment setting | Outcomes measured | Design | Method | Intervention | Control | Overall study quality | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Raes et al. (2011) [28] ‘The effect of using assessment instruments on substance-abuse outpatients' adherence to treatment: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial’. |

N = 227 clients. Clients: Patients with diagnosed DSM-IV substance abuse/dependence for at least 1 substance, exclusive single alcohol abuse or dependence. Setting: 5 outpatient drug treatment centres from ‘De Sleutel’ treatment network in Belgium, doing individual counselling sessions. |

Treatment adherence (total number of sessions attended by the client). | Between-subjects randomised controlled trial. | Clients randomly assigned to intervention or control group. Outcomes measured for 12 weeks. Intervention group regularly completed RCQ [46] and PREDI [47] assessments during individual counselling sessions. RCQ measured clients' stage of change. PREDI measured clients' personal resources and wish to change. Clinicians provided immediate feedback to clients at each session (frequency of sessions not specified). RCQ feedback included graphs and worksheets about clients' stage of change. PREDI feedback identified clients' personal resources. | RCQ and PREDI assessments completed by clients and feedback provided directly to clients by clinicians during individual counselling sessions. | No assessments or feedback provided. | Good | Overall, improvement in treatment adherence in feedback group. In the ITT analysis: (i) Assessments plus feedback significantly increased treatment adherence at and beyond 8 sessions. 53.4% adherence in feedback group compared to 34.2% in control group (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.1). (ii) Assessments plus feedback increased treatment adherence at and beyond 12 sessions. 33.6% adherence in feedback group compared to 20.7% in control group (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0–2.5). |

Østergård et al. (2021) [29] ‘The Partners for Change Outcome Management System in the psychotherapeutic treatment of cannabis use: a pilot effectiveness randomized clinical trial’. |

N = 100 clients. N = 16 clinicians. Clients: Cannabis use as primary drug problem. Setting: Outpatient drug use treatment centre in Odense, Denmark. |

Primary outcomes: Rate of attendance to treatment sessions. Dropout rate. Secondary outcomes: Abstinence from cannabis use. Number of days using cannabis during last 30 days. Current other drug use. |

Between-subjects randomised controlled trial. | Clients randomly assigned intervention or control group. Clients in control group received weekly therapy sessions for 8 weeks. Clients in intervention group completed ORS [1] and SRS [2] at weekly therapy sessions. Feedback given immediately to clinicians at weekly sessions with information regarding clients' risk of drop-out. Clinicians encouraged to discuss with clients, thereby also providing feedback to clients. | ORS and SRS assessments completed by clients and scores provided to clinicians and discussed with clients. | No assessments or feedback provided. | Fair | No significant difference in attendance rate or dropout rate between feedback and control groups. Mean attendance rate increased non-significantly from 0.65 in control group to 0.66 in feedback group (p = 0.88). Mean dropout rate decreased from 56.1% in control group to 51.2% in feedback group (p = 0.82). No significant difference in cannabis or other drug use between feedback and control groups. |

Stanley-Olson (2017) [30] ‘Client feedback and group therapy outcomes for adults with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse’. |

N = 21 clients. N = 5 clinicians. Clients: Aged 18 and above, with co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse, participating in group therapy. Setting: Psychiatric clinic providing residential and outpatient treatment. |

ORS [1] (Miller and Duncan, 2000) scores. Rate of attendance to treatment sessions. Dropout rate. |

Within-subjects single-case reversal design. | Outcomes measured 4-weeks pre-intervention (phase A) and 4-weeks post-intervention (phase B). Sequence repeated so control and intervention phases each carried out twice (ABAB). Clients in control phase completed the ORS [1] at group psychotherapy sessions and no feedback was provided to clinicians or clients. Clients in intervention phase completed ORS and GSRS [42] at group psychotherapy sessions and feedback reports containing graphical and verbal data provided weekly to both clinicians and clients. | GSRS assessments completed by clients and feedback provided to clinicians and clients. | No feedback provided. | Poor | No significant difference in ORS scores between feedback and control conditions. No significant difference in treatment attendance or dropout rates between feedback and control conditions. Participant attendance rates were 84% for control phase 1, 86% for intervention phase 1, 77% for control phase 2 and 84% for intervention phase 2. Qualitative interview questions about routine assessment and feedback generated mixed answers and revealed a similar number of clients found the process useful as those that did not. |

- Note: Effect sizes and p-values supplied as described by authors and may vary in format.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition; GSRS, Group Session Rating Scale; ORS, Outcome Rating Scale; PREDI, Personal Resources Diagnostic System; RCQ, Readiness to Change Questionnaire; RR, risk ratio; SRS, Session Rating Scale.

2.4 Risk of bias assessment

We based our assessment of evidence quality and risk of bias on the quality assessment tools developed by the National Institutes of Health (see https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools) and outlined in detail in the Systematic Evidence Review from the Blood Pressure Expert Panel, 2013 [32], one of the reports recommended on the website for guidance on how to apply the tool. As stated by the panel, the NIH quality assessment tools were ‘designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study … not … to provide a list of factors comprising a numeric score’ [32; p. 82, appendix A]. Based on the studies returned by our literature review we used the tool for (i) Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies; and (ii) Quality Assessment Tool for Before–After (Pre–Post) studies with No Control Group.

Two authors (IC and LM) reviewed the quality of each of the papers using the tools described above and assigned an assessment of good (low risk of bias), fair (moderate risk of bias) or poor (high risk of bias) to each. If the ratings differed, the reviewers discussed the article until a consensus was reached.

2.5 Evidence synthesis

There was considerable heterogeneity in the study designs and outcome measures of the included studies, making it difficult to directly compare studies. Due to this heterogeneity, and the small number of studies identified, a formal meta-analysis was not performed. Instead, the evidence was synthesised narratively. We have organised the synthesis of study results firstly by whom the feedback was provided to—clinicians only, clients only and clinicians plus clients—and secondly by which outcomes were measured. We have also reviewed client and treatment characteristics and timing of feedback across studies.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study selection

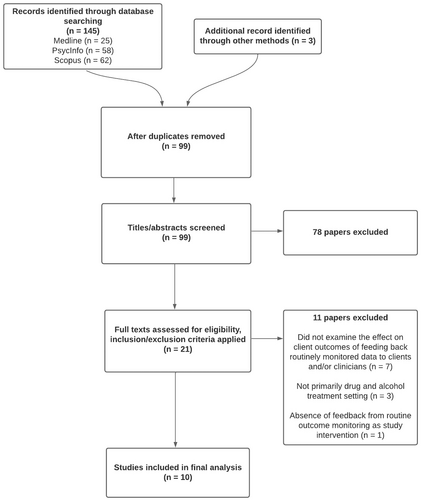

Our PRISMA flowchart is shown in Figure 1. The search strategy yielded 99 papers without duplicates through database searching, citation chaining and manual searching. After screening titles/abstracts, 21 papers remained. Full texts were then assessed for eligibility by applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed above. A further 11 papers were excluded: seven did not examine the effect on client outcomes of feeding back routinely monitored data to clients and/or clinicians, three were not conducted primarily in AOD treatment settings and one did not have feedback from ROM as the study intervention. A final group of 10 papers was included in this study, each reviewed by at least two authors. This information is summarised in Tables 1–3.

3.2 Types of study

Of the 10 studies reviewed, five were controlled intervention studies, involving randomisation of participants (whether clients or clinicians or both) to either feedback or control groups, and five were treated as before–after (pre–post) within-subjects studies with a control condition. When performing our quality assessment of the included studies, we assessed the Miller and colleagues [21], McCaul and Svikis [33] and Seitz and Mee-Lee [34] studies based on the criteria for Before–After studies because, while important details of study design and analysis were not reported in these studies, it was clear they involved some kind of repeated-measures design with a within-subjects control condition but had no separate control group.

3.3 Study quality

See Tables S1 and S2 for details of how quality ratings were assigned to each individual study.

3.3.1 Feedback provided to clinicians only

Six of the 10 studies included in this review involved an intervention where feedback was provided to clinicians. A summary of their findings is presented in Table 1. Of the six, three we deemed to be good-quality studies, involving either randomisation to treatment or a pre–post comparison, objective assessments of outcome, with sufficient sample size, and using appropriate statistical methods described in detail. The three studies we deemed to be of poor quality were given this designation primarily because of omission of important details about methods or analyses conducted [21, 33, 34].

Of the three good-quality studies, one found that feedback had no significant effect on any of the outcomes measured; substance use, therapeutic alliance or attendance [26]. Two of the three found a significant effect of feedback. In one study [27], clients deemed to have gone off-track—that is, clients whose level of improvement was deemed by clinicians to be unsatisfactory—reported significantly greater reduction in alcohol use and significantly greater improvement in global function during the feedback phase of the trial than during the control (i.e., non-feedback) phase. In the other good-quality study [40], clients in the group whose clinicians received feedback had significantly higher post-treatment global function scores and rates of clinically significant improvement, significantly better clinician perceptions of client outcomes, and significantly greater attendance rates, than clients in the group whose clinicians received no feedback.

3.3.2 Feedback provided to clinicians only

In one of the 10 studies reviewed [43], feedback was provided to clients only. A summary of its findings is presented in Table 2. We assessed this study as being of good quality for the same reasons as the good-quality studies listed previously: randomisation to treatment, objective assessments of outcome, sufficient sample size and appropriate statistical methods. It found a significantly greater improvement in stress and anxiety in the feedback group than in the control group.

3.3.3 Feedback provided to clients and clinicians

In three of the 10 studies, the intervention involved providing feedback to clients and clinicians. A summary of their findings is presented in Table 3. Of these three we rated one study as being of good quality, one of fair quality and one of poor quality. The good-quality study [28] was deemed good because of the reasons listed previously. This good-quality study found that feedback did improve treatment retention. The fair-quality study [29] found no significant difference in treatment retention between feedback and non-feedback groups. Although this study did randomise participants and have sufficient numbers, treatment adherence was very low, with the instruments used to monitor outcomes (Outcome Rating Scale and Session Rating Scale) administered, and therefore fed back to clients and clinicians, in only 40% of cases. We deemed this to be a serious limitation. The poor-quality study [30] was conducted quite well, but the sample size of 21 clients and five clinicians was simply too small to draw meaningful conclusions from.

3.4 Outcomes

Table 4 shows the outcomes measured by the six good- or fair-quality studies. The cells shaded grey indicate that the differences observed between the feedback and control groups/conditions were significant for the outcome in question. Four out of six studies found a significant improvement in at least one outcome: two out of three clinician-only feedback studies, one out of one client-only feedback studies, and one out of two client and clinician feedback studies. Only one study [27], a clinician-only feedback study, found that feedback was associated with significant improvements (i.e., reductions) in substance use, and this was not overall, but only for those subjects who were deemed to be off-track. Two studies found feedback to be significantly associated with treatment retention, one a clinician-only feedback study [40] and one a clinician and client feedback study [28]. Two studies, both clinician-only feedback studies [27, 40], found feedback to be associated with improvements in global functioning/wellbeing, and one of these studies [40] also found feedback to be positively associated with therapeutic alliance and clinicians' perception of client outcomes. And finally, the sole client-only feedback study found feedback to be significantly associated with reductions in anxiety and stress [43].

| Clinician-only feedback | Client-only feedback | Feedback to clients and clinicians | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes measured | Crits-Cristoph et al. 2010 [26] | Crits-Cristoph et al. 2012 [27] | Schuman et al. 2015 [40] | Andersson et al. 2017 [43] | Raes et al. 2011 [28] | Østergård et al. 2021 [29] |

| Substance use | x | x | x | x | ||

| Treatment retention/attendance | x | x | x | x | ||

| Global function/wellbeing | x | x | ||||

| Therapeutic alliance | x | x | ||||

| Organisational readiness for change/job satisfaction | x | |||||

| Clinician perception of client outcomes | x | NAa | ||||

| Anxiety/depression/stress | x | |||||

- Note: x designates whether the outcome in question was measured, grey shading designates outcomes where a significant difference was found between feedback and control group/condition for that outcome.

- a Not applicable because client-only study.

3.5 Client and treatment characteristics

Treatment settings and modalities were relatively consistent across the good/fair-quality studies, with all participants attending counselling as outpatients. Client characteristics were also similar, with all studies recruiting adults, except for one whose participants were adolescents and young adults under 25 years [43]. Most studies did not restrict their sample to one primary drug of concern, except one study where all participants were being treated for cannabis dependence [29]. This consistency in setting, modality, age and sampling of clients makes it difficult to determine whether these factors influence outcomes in any way as there are no alternative groups available to compare against.

3.6 Timing of feedback

Most studies provided feedback in a regular timely manner weekly or twice weekly. For the four good/fair-quality studies that provided feedback weekly or twice weekly, two showed significant improvement in some outcomes [27, 43] while two studies did not [26, 29]. Unfortunately, the other two good-quality studies [28, 40] did not specify the frequency of feedback, so although both these studies showed improvement in outcomes it is difficult to draw any conclusions about the role timing of feedback may have played in improving outcomes.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Interpretation of findings

The results of our review suggest that while there is some encouraging preliminary evidence to suggest that providing AOD clients and/or clinicians with feedback is associated with improved client outcomes, overall there is not enough good quality evidence to draw any firm conclusions.

With the search parameters we used we could only find 10 experimental clinical AOD studies that had addressed the question of whether feedback from ROM improved patient outcomes, and of these only six were of good or fair quality as evidence. Feedback was provided to clinicians only in three of these studies, to clients only in one, and to both clients and clinicians in two.

Perhaps of most concern is the fact that only one good-quality study [27], from among the four that measured it, found that providing feedback was associated with reduced substance use among clients, and this was only among a subset of participants, the off-track clients. Four good-quality studies found feedback significantly improved psychosocial constructs that could be considered precursors to substance use—for example, treatment retention (two studies) [28, 40], global function/wellbeing (two studies) [27, 40], therapeutic alliance (one study) [40] and mood symptoms (one study) [43]. However, while it appears as if feedback may have some effect on these ‘upstream’ constructs, in AOD settings reducing frequency and quantity of substance use is the proximal goal of treatment. The apparent lack of a reliable association between feedback and substance use prevents us from concluding that it is an effective AOD intervention yet.

In addition, two of the good-quality studies failed to find any effect of feedback for any of the outcomes they measured [26, 29]. One of these, Crits-Cristoph and colleagues [26], was by far the largest study—over 1500 clients and 118 clinicians—so the absence of a significant finding across all the outcomes measured seems especially telling. The authors provide several possible reasons for the absence of a result: low levels of substance use among clients at the start of treatment creating a floor effect; a ceiling in therapeutic alliance scores; and aggregated caseload feedback instead of individualised client feedback. This latter methodological limitation was corrected in their follow-up study [27], where individualised client feedback was provided to clinicians. This change appeared to be effective as substance use among the off-track clients in the group of clinicians that received feedback was significantly lower than among the off-track clients whose clinicians did not. This finding supports the theory that clinicians who receive regular timely individualised feedback about their clients' substance use and general functioning are better able to identify when specific clients are not doing well and respond quickly to provide additional care and support. However, once again, more studies are needed.

A wide range of outcomes was measured by the studies we reviewed (see Table 4). Of these, treatment retention and global function/wellbeing have the most support for efficacy of feedback, each with positive findings in two studies; however, once again this is not enough to draw any conclusions. Overall, there was considerable variation in the methods employed and the outcomes measured by the studies we reviewed. Some fed back information to clinicians, some to clients, some to both; some studies measured substance use and some did not; some focused on therapeutic alliance and others on global functioning. The small number of studies, their heterogeneity, and the absence of a positive association between ROM with feedback and substance use means that, at present, we cannot definitively conclude that ROM with feedback leads to better outcomes for AOD clients.

4.2 Relevance and future implications

There is ample evidence that ROM and feedback improve client outcomes in mental health treatment settings [6-14]. An obvious assumption was that what worked in mental health settings would translate well to AOD treatment; however, at present, and until more quality studies are conducted, we cannot conclude whether this is the case. Important questions that still need to be answered are to whom feedback should be delivered (clients or clinicians or both), when feedback should be delivered, what sort of information should be contained in the feedback and what action should be taken after feedback. For example, it is likely that a different set of mechanisms would operate when information is fed back to clients than when it is fed back to clinicians. Future studies should compare three groups—feedback to clients only vs. feedback to clinicians only vs. feedback to both—in the same study.

All the studies we reviewed were conducted in the context of AOD counselling and therapy. As such, the focus in most studies we reviewed was on constructs integral to counselling such as therapeutic alliance, mood and psychosocial functioning. These constructs are of course important but the way we assess the efficacy of AOD ROM and feedback interventions should primarily be via its effect on objective clinical endpoints (e.g., clients' substance use) rather than focusing on potential mechanisms of change (e.g., therapeutic alliance). Furthermore, feeding back client information to clients and clinicians should be researched in other treatment contexts (e.g., during routine case management by doctors or nurses), not just counselling.

Timing of feedback was also relatively consistent across studies, with most studies providing feedback weekly or at every session, however with such a low number of studies and variation in methods across studies, it is difficult to know what specific effect timing of feedback may have had on client outcomes. Future studies should more closely examine how the timing of feedback may affect outcomes, as well as the type of feedback and what information it contains.

Finally, and importantly, the studies we reviewed placed little emphasis on measuring what clinicians or clients actually did with the feedback they received. Determining how clinicians and clients are using feedback will be crucial in identifying the precise mechanisms by which feedback leads to better outcomes, if this proves to be the case.

4.3 Study limitations

This review had several limitations. Although more than one reviewer reviewed each paper and performed the quality assessment, only one reviewer was involved in the study selection process, which increases potential for introduction of selection bias. Only articles written in English were included in the search, potentially reducing the search's yield. A further limitation is that this review was not pre-registered. However, while pre-registration does create transparency in the research process and safeguard against researcher bias, the absence of pre-registration on its own does not indicate the presence of these biases.

5 CONCLUSIONS

ROM is now common in medical settings around the world, and feedback from ROM has been used successfully in mental health settings. Disappointingly however, given this powerful resource already at our disposal, the efficacy of feedback from ROM has been under researched in AOD settings. The small number of good-quality studies and their heterogenous methods and findings make it difficult to reach any firm conclusions about the effect of feedback on AOD clients' outcomes. It is possible to say that there is some preliminary evidence that ROM and feedback may improve treatment retention, global functioning/wellbeing, mood symptoms and substance use among off-track clients, but overall more quality research needs to be conducted before we can reach any firm conclusions about its efficacy as an intervention.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Each author certifies that their contribution to this work meets the standards of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None to declare.