Education of Afghan refugee children in Iran: A structured review of policies

Abstract

Iran has been among the top ten largest refugee-host countries worldwide, sheltering one of the largest groups of forced migrants from Afghanistan during the past four decades. This policy paper briefly examines and summarizes the policies related to education of Afghan children in Iran through a structured review. The results of this review suggest that higher education has been and continues to be heavily restricted for Afghans. While access to primary education has improved for Afghans in Iran, policies continue to neglect both cultural specificity and unique needs of this group. Therefore, enrolment has remained restricted. The findings of our policy analysis call for further attention to culturally relevant education, financial assistance for families living in poverty and interventions to subsidize the cost of education to ensure access of all Afghan children to primary education and retain enrolment. Results also call for reconsiderations in restrictive higher education policies for Afghans in Iran.

The population of forcibly displaced people reached the record-high number of 100 million in 2022 (United Nations, 2022). By 2019, over 20 million of the forcibly displaced people have been officially recognized as refugees (UNHCR, 2020b). Refugees are forced migrants who escaped their countries of origin with fear of persecution and their status as refugees has been recognized by the authorities of their host country. Conflicts, wars and serious disruptions in the public order are the major reasons for the forced displacement of refugees (UNHCR, 2020b). Afghans are one of the largest groups of refugees in the world; their country of origin has been in conflicts and wars since the mid-1970s (Faropoulos, 2015).

Instability in Afghanistan started with political disputes around 1975 and followed by a coup in 1978 (Schmeidl & Maley, 2008). In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support the coup, but the rise of the Mujahideen and the heavy costs of the war forced them to withdraw from the country in 1989 (Faropoulos, 2015). In 1996, the Taliban assumed control and power over most parts of Afghanistan, which created further conflicts in the country (Qadeem, 2005). Between 2001 and 2014, the United States-led war created more instability in the country (Naseh, Potocky, Burke, & Stuart, 2018; Simpson et al., 2017). In May 2021, the Taliban surged back to power, and forced displacement of Afghans increased once again. It is expected that Afghans remain among the top five refugee populations in the world for the upcoming years.

Over 90% of the Afghans who left their country to seek protection as refugees live in Iran and Pakistan, the two neighbouring countries of Afghanistan (UNHCR, 2018). Escape is usually abrupt and unplanned for forced migrants, and it is common for them to seek protection in the nearest safe place or safe country. Available data and reports suggest that between one and a half million and three million Afghans live in Iran, out of which around one million are officially recognized as refugees, between half a million to two million are under-documented (do not have legal documents recognized by the Iranian government for their stay), and over half a million have valid passports and visas (Naseh et al., 2019; Shammout & Vandecasteele, 2019; UNHCR, 2018). Estimates from 2015 suggest that among the population of around 2.4–3 million Afghans in Iran at least 800 000 were children (Khonsari & May, 2015). The population of Afghans in Iran is growing, Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) recently reported that since the Taliban takeover, more than 300 000 new Afghans arrived in Iran to seek protection (NRC, 2021).

In the 1970s Iran opened its borders to welcome the first wave of forcibly displaced Afghans (Naseh, Potocky, Stuart, & Pezeshk, 2018). Afghans who arrived in Iran in this period were recognized as immigrants and granted ‘blue cards’. Blue cards were identification cards allowing mainly Afghans and Iraqis to enjoy similar rights as Iranians in the country (Margesson, 2007). These cards were voided by the Iranian government between 1993 and 1995 and replaced with temporary documentation (Rajaee, 2000). Along with voiding blue cards, Iran started limiting the access of refugees to certain subsidized services in the country (Garakani, 2009; Naseh, Potocky, Stuart, & Pezeshk, 2018). In 2003 Iran introduced Amayesh cards: temporary documentations issued by the Iranian Bureau for Aliens and Foreign Immigrants Affairs (BAFIA) through an integrated registration system for refugees (Adelkhah & Olszewska, 2007). Amayesh cards have remained the official legal documents for refugees in Iran. Refugees have to pay a fee to get their Amayesh card when a new round of registration is announced by BAFIA. Failure to renew Amayesh cards in a timely manner can change an Afghan refugee's status to an under-documented immigrant in Iran (Naseh, Potocky, Stuart, & Pezeshk, 2018).

BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON AFGHANS ACCESS TO EDUCATION IN IRAN

The first wave of forced Afghan migrants who received blue cards had access to most subsidized services, including the Iranian free education system, but under-documented Afghan children were excluded (Margesson, 2007). In response to this exclusion, Afghan communities started self-governed schools or Madares-e Khodgardan to provide education to under-documented immigrants beginning in the early 1980s (Hugo et al., 2012). These schools had volunteer teachers and very low tuition fees to cover operation costs (Herve, 2018), but in 2000 their operation was deemed illegal due to the allegedly lower quality of education (Squire, 2000). Under-documented Afghan children had difficulty accessing education until 2015, when the Iranian Supreme Leader decreed that all Afghan children, including under-documented school-aged children, should be able to access education in Iran and enrol in Iranian schools (NRC, 2017).

As a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, Iran recognizes refugee rights including the right to access primary education with some reservations (Abbasi-Shavazi et al., 2008). Iran's reservations on Articles 17 and 24 of the 1951 Refugee Convention limit refugees' access to the job market (Naseh et al., 2019). Reservation on Article 23 of the 1951 Convention puts limits on refugees' access to subsidized services including the Iranian free education system (Barr & Sanei, 2013). Reservations on Article 26 of the Convention prevent refugees from living and going to schools in specific provinces marked as no-go-areas for refugees and limit their movements between provinces (Naseh et al., 2019). Iran is a signatory to the Convention on the Rights of the Child as well, mandating that countries to make primary education required and free for all school-aged children (Herve, 2018). Moreover, the country has ratified the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, requiring member states to provide free primary education and make secondary education accessible. During the past decades Afghans' access to education in urban and rural areas of Iran changed with multiple revisions in relevant policies while access to available primary and secondary education in refugee settlements remained unchanged and free of charge. Less than 10% of the Afghans population in Iran lives in settlements.

Adelkhah and Olszewska (2007) reported that only about a third of the school-aged Afghan children in Iran were studying at Iranian schools in 1998. A study conducted 5 years later (Naseh, Potocky, Stuart, & Pezeshk, 2018) estimated that the enrolment rate of Afghan children in official or unofficial schools in Iran had increased to over 90%. In a published study in 2017, school enrolment rate for Afghan children was estimated around 75% (Shakib, 2017). Estimated school enrolment rates for Afghan children have remained below the national average for primary education in Iran (Herve, 2018).

Although Iran has been a host to over a million Afghans for more than four decades, data on access to education among Afghans in this country and consequently studies in this area have remained scarce (Herve, 2018). To our knowledge, this policy review is among the first to critically and systematically review education policies for Afghan refugees in Iran to identify trends in access to education for this population.

METHODS

Search strategy

To identify the policies relevant to the education of Afghans in Iran, we conducted an online systematic search in two governmental databases of legal documents: Islamic Parliament Research Center of the I.R. of Iran and Laws and Regulations Portal of the I.R. of Iran. The search was conducted in two steps: First, keywords relevant to immigrant, refugee, alien, Afghan and foreign were searched with filtering for dates between January 1979 and October 2020; then, in the list of the retrieved policies, we searched for keywords relevant to students, children, adolescents, school and education. Filtering for dates was based on the start of the first wave of forced migration from Afghanistan to Iran, which coincided with the Islamic revolution in Iran. Retrieved policies through this two-step search were independently reviewed by the authors for inclusion in the policy review. In addition to our online systematic search in two governmental databases, we searched the online archive of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Education (MOE); website of two national non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in the education of refugee children; and reports by UNHCR, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and Iran's National Commission for UNESCO to find references to policies relevant to education of Afghans in Iran.

Analytic strategy

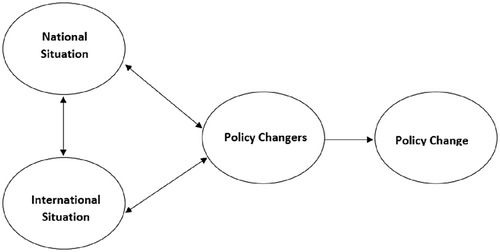

We used an adjusted version of the Cappiccie Lawson evolution immigration model (CLEIM; Cappiccie, 2011) to systematically review and analyse the retrieved education policies in this review. The CLEIM provides an integrated template to examine immigration policies and the forces driving the policy change. The CLEIM was originally designed for analysing macro immigration policies. In this study, we adjusted the model to use it for education policies based on the available information that we could access. Two authors went through the identified policies and applied the CLEIM model for each one. They each independently conducted the review and then compared their results to resolve discrepancies through discussion.

The adjusted CLEIM model (Figure 1) shows how the interplay of different forces influences policy-makers to make a policy change. National context includes economic conditions, the general attitude towards immigrants and openness of the society and political atmosphere. International context includes foreign policy, human rights policy, humanitarian aid decisions, bilateral and multilateral economic, social and political agreements and conflicts (Cappiccie, 2011). In these national and international contexts, there are actors of influence that although they do not occupy any official position, they influence the policy change. Examples are interest groups, media, political fractions and think tanks (Cappiccie, 2011). The interplay of the national and international situations and influence groups make an impact on policy changers who are local and national actors with the authority to write and implement policies. In Iran, there are three different bodies and their subdivisions with such authority: the executive branch including the President's office, ministries and governors; the legislative branch (i.e. the Parliament); and the judicial branch and law enforcement agencies. As it is shown in Figure 1, interplay and interchange between the factors that drive change to a policy are bi-directional. This means that either of these factors can impact one another which ultimately makes a change in policy. For instance, an international situation can provoke a national response which in turn can encourage a policy change or vice versa.

RESULTS

Our search yielded 14 policies on education of Afghan refugees and immigrants in Iran. The policies were issued between 1980 and 2020. None of the policies were developed or approved by the parliament (the legislative body); they all were passed by the executive entities. Six of the policies were introduced and implemented by the MOE, three by the High Council of Cultural Revolution, two by the Cabinet of Ministers, two by the High Council of Education and one by the Coordination Council for Foreign Nationals—all under the President's office. Table 1 shows the review of each policy according to the adjusted CLEIM model.

| Name of the policy (Date) | Policy change (Decision maker) | Context |

|---|---|---|

| The circular on school registration of foreign national students in the 2020–2021 academic year (2020) | Children born to Iranian mothers and Afghan fathers were allowed to register in Iranian schools without limitations (The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution) |

National context

International context

|

| The regulation on the education of foreign nationals (2016) | Under-documented Afghans were allowed to enrol in Iranian schools (Cabinet of Ministers) |

National context

International context

|

| The circular on the tuition of the foreign national students (2014) | Tuition was waived for Afghan students for one academic year. (Deputy Minister of Education in International Affairs) |

National context

International context

|

| Amendment of the facilitating conditions for Afghan and Iraqi residents in Iran to continue their school and university education Article (2011) | All documented Afghan and Iraqi students were allowed to register at Iranian schools and continue their education (The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution) |

National context

International context

|

| The facilitating conditions for Afghan and Iraqi residents in Iran to continue their school and university education Article (2009) | Under-documented Afghan children were given access to short-term educational programs (The Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution) |

National context

International context

|

| The regulation on the education of foreign nationals (2003) |

(The Coordination Council for Foreign National) |

National context

International context

|

| The resolution on decision making on literacy classes for Afghan immigrants and 10 milliards Rial appropriation and budget allocation for the education of out-of-school Afghan children or illiterate adults (2000) |

(Cabinet of Ministers) |

National context

International context

|

| The regulation on the establishment of special private schools for foreign nationals (1999) | Iranian nationals were permitted to establish private schools for foreign nationals (The High Council of Education) |

National context

International context

|

| The resolution on the admission of a higher number of Afghan students at Iranian universities (1990) | Iranian universities were permitted to admit more Afghan students (The High Council of Education) |

National context

International context

|

| The resolution on the evaluation of Afghan refugees' educational documents (1983) | The evaluation and acceptance of educational documents of Afghan refugees were permitted contingent on the approval of the Ministry of Interior (Ministry of Education) |

National context

International context

|

| The circular on registration and enrolment of refugee children from foreign countries in Iranian schools (1983) | Documented refugees and foreign students who did not have their prior educational documents were allowed to register in Iranian schools (Ministry of Education) | |

| The regulations on the establishment of schools for foreign nationals (1981) | The establishment of schools by foreign diplomatic missions for their respective citizens was permitted (Ministry of Education) |

National context

International context

|

| The resolution on the evaluation of Afghan refugees' educational documents (1981) | Committees of evaluation of foreign educational documents were permitted to refrain from accepting educational documents of foreign students at their discretion (Ministry of Education) | |

| The resolution on the education of Afghan refugees (1980) |

• Documented refugees were permitted to enrol in Iranian schools • An evaluation system for placement of new students was established • Afghans were allowed to receive certificates and diplomas upon completion of their education in Iran (Ministry of Education) |

National context

International context

|

From 1979 to 1990, five policies relevant to Afghans' education in Iran were approved and implemented by the newly established government. In 1980, a resolution was passed to officially allow documented Afghan children to register at free Iranian schools and study the nationalized standard curriculum (Ministry of Education of the I.R. of Iran, 1980).

Less than a year from the approval of the 1980 resolution, a new resolution was passed to allow the committees for the evaluation of foreign educational documents to refrain from accepting educational documents of foreign students based on their discretion (Ministry of Education of the I.R. of Iran, 1981a). In the same year, MOE also passed a regulation to allow diplomatic missions in Iran to establish schools for their citizens (Ministry of Education of the I.R. of Iran, 1981b). After the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, all schools had been nationalized in the country (Squire, 2000), but this regulation allowed the establishment of private schools by diplomatic missions.

During the 1990s, Iran started to rebuild the country following the end of the war with Iraq. In Afghanistan, the Taliban took power in most parts of the country. With the rise of the Taliban, Afghanistan–Iran relations deteriorated and Iran closed its border with Afghanistan in 1995 (Milani, 2006). In 1992, Iran signed a tripartite repatriation agreement with UNHCR and the Afghan government to facilitate the return of Afghans (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2005). Between 1990 and 1993, nearly one million Afghan refugees used the repatriation assistance provided by the UNHCR and returned to Afghanistan (Turton & Marsden, 2002). However, many more escaped to Iran with the rise of the Taliban (Rajaee, 2000). In 1998, Iran limited Afghan access to the Iranian job market by setting penalties for employers working with under-documented Afghans (10 923/77/11998). During these years Iran's policy towards Afghans further shifted to limit the access of under-documented immigrants to services including education, but the country remained welcoming towards documented refugees (Rajaee, 2000).

In 1990, a resolution was passed by the President and Chairman of the High Council of Education allowing a higher number of documented Afghans to register at Iranian universities (336/DSH, 1990). In 1999, when Iranian schools were struggling to provide education to Iran's baby boomers, the High Council of Education passed a regulation to give permission to Iranian nationals to establish private schools for foreign nationals including Afghans (120/2653/81999).

Between 2000 and 2010, Iran was at a diplomatic impasse with the international community for its nuclear program. The country was under heavy sanctions and intensifying international pressure. Following the 9/11 event, the overthrow of the Taliban, and the establishment of a new government, Iran offered assistance in establishing and maintaining peace in Afghanistan and providing help for the reconstruction of the country (Milani, 2006). During this period, Iran put further restrictions in place to encourage and occasionally force repatriation of Afghans (Naseh, Potocky, Burke, & Stuart, 2018). During these years almost all self-governed Afghan schools were closed down by the government with the justification that these schools are providing low-quality education in unsafe settings (Herve, 2018).

In 2000, the Cabinet of Ministers passed a resolution allocating budget to the literacy movement organization to provide literacy training to documented and under-documented Afghan children and illiterate adults (49 181/T/25595/H 2000). This policy is among the first to introduce a tailored educational program for under-documented Afghan children. In 2003, the first structured code of conduct on the education of Afghans in Iran was passed (423/T/29982/H, 2003). This policy officially instructed schools to only register documented Afghans with valid Amayesh cards from the province that the school was located in. This code of conduct also allowed national schools to receive tuition from Afghan students and prevented Afghans from enrolling in the 1-year pre-university program, which is required to enter Iranian universities. Following the new limitations in accessing education for under-documented Afghans, in 2009, the Iranian Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution passed a policy allowing short-term educational programs for these children (45 245/88/DSH 2009).

Within the past 10 years, Iran has continued to invest in repatriation of Afghans. Despite scarcity of resources in Iran, partly due to sanctions, the access level of Afghans to primary education has enhanced following the Iranian Supreme Leader decree on education (NRC, 2017). In 2014, tuition was waived for 1 year for Afghan refugees following the circular on the tuition of the foreign national students by the Deputy Minister of Education for International Affairs (Ministry of Education of the I.R. of Iran, 2014). In 2020, a bill was passed to allow children of Iranian mothers and Afghan fathers to receive Iranian citizenship that facilitated the access of these children to education in Iran (15 519 2020). While access of Afghan children to primary education improved between 2010 and 2020 in Iran, access to higher education in remained limited and become even more complex. In 2011, the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution passed an amendment to its 2009 policy, emphasizing that all Afghan and Iraqi students can register at the Iranian schools and continue their education (10 644/89/DSH 2011). However, in 2012, a regulation was put in place requiring Afghans to renounce their refugee status, return to Afghanistan to get an Afghan passport, and return to Iran as immigrants with a temporary education visa if they want to study at Iranian universities (Herve, 2018).

DISCUSSION

The essential role of education for refugees has been recognized internationally (UNESCO, 2017; UNHCR, 2016). However, policies of host countries can prevent refugees from accessing education while in exile. Our findings show that the policies for education of Afghan refugees and immigrants in Iran have been partly impacted by Iran's macro policy towards and its relations with Afghanistan. Iran's Afghanistan policy after the 1979 revolution in Iran and the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan was shaped around Islamic solidarity. While in the 1980s, Iran was dealing with the aftermath of the Islamic revolution, the US imposed sanctions and the ongoing war with Iraq, Afghans were welcomed in the country (Safari, 2011). In these years, Iran's hospitality was promoted as sheltering Muslim brothers and sisters fleeing Soviet invasion in Afghanistan. Some researchers argue that the open-door policy of the country during these years was out of necessity rather than Islamic solidarity as Iran needed the workforce and the newly established government did not have the capacity to control the border with Afghanistan or process refugee applications (Esfahani & Hosseini, 2018). During these years, education was only accessible for documented Afghans in Iran, but under-documented Afghans were not officially excluded from accessing education. Afghans could enrol in Iranian schools to study standard curriculum with tuition decisions made by local school management.

During the 1990s, with the end of the 8-year Iran–Iraq war, the priority of the Iranian government became the reconstruction of the country and thus its refugee policy shifted to border enforcement and repatriation encouragement (Rajaee, 2000). There was no major policy change regarding the education of Afghans in Iran during this period, except allowing individuals to establish private schools for foreign nationals. During these years Iran's baby boomers were reaching school age and the nationalized Iranian school system was struggling to fulfil the growing demands for education.

Between 2000 and 2010, Iran put further restrictions on Afghan refugee access to services in the country. Restrictive policies in this context were partly due to Iran's pledge to the reconstruction of Afghanistan and the establishment of an interim government following the fall of the Taliban, and partly due to its deteriorating economy under unprecedented international sanctions. In 2003, the first structured code of conduct for the education of Afghans in Iran was introduced, which was by far one of the most restrictive education policies for Afghans in Iran. This policy not only excluded under-documented Afghans from accessing education in Iran but also forced many documented children to drop-out due to the lack of financial resources to cover the added tuition (Herve, 2018). Iran passed two additional policies in this period to provide short-term and limited educational programs for under-documented children, but the missed educational opportunities in this period have impacted generations of Afghans. This was also the period that self-governed schools were deemed illegal by the Iranian government and began to be shut down. Beyond being a way for under-documented Afghans to receive education, self-governed Afghan schools were the only educational institutions in Iran providing cultural education and information about the history of Afghanistan for Afghan students (Squire, 2000).

Although during the past 10 years the emphasis of the government of Iran remained on encouraging repatriation of Afghans, two events have enhanced Afghan children's access to primary education in the country. The Iranian Supreme Leader decree in 2015 resulted in policy changes that allowed under-documented children to enrol in Iranian schools, and the passage of the citizenship bill for children of Iranian mothers married to foreigners in 2020 gave children of Afghan fathers and Iranian mothers similar access to education as Iranians. Despite recent improvements, the added tuition fees as part of the code of conduct for the education of Afghans continue to limit access for many Afghan children to Iranian schools. A significant number of Afghan households in Iran live in poverty (Naseh, Potocky, Burke, & Stuart, 2018). The decline in Iran's economy and the COVID-19 pandemic has further limited the financial ability of Afghan households and consequently the access of Afghan children to education in Iran. Online education for children during COVID-19 requires access to a mobile device or computer and stable internet that means additional expenses.

Despite the enhanced access to primary education in recent years for Afghans, access to higher education has remained restricted. Refugees are required to renounce their legal status as refugees and leave the country to re-enter as immigrants with temporary student visas.

LIMITATIONS

Lack of data on education and education outcomes of Afghan refugees in Iran allowed us to only conduct a general review of the relevant policies. Iran considers Afghans a politically sensitive group and limits the access of organizations or groups to data on this population.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Although many restrictions for Afghan children access to education in Iran have been lifted in recent years, tuition fees are still a significant impediment. Considering the high rates of income poverty among Afghans (Naseh, Potocky, Burke, & Stuart, 2018), many Afghan families cannot afford tuition fees or costs associated with schooling for their children. Many are forced to send their children to work to contribute to family livelihood rather than shouldering the cost of education. Estimates show that around half of the street children in Iran are Afghans (Vameghi et al., 2019). Targeted and free of charge educational programs are needed for these children. MOE waives tuition for highly vulnerable Afghan children in Iran, but the process of getting a waiver could be complex. Moreover, many Afghan children might need help with the costs associated with education such as cost of transportation and school supplies. Schooling is hypothetically free for Iranians (Squire, 2000), but most schools demand voluntary donations, that can create another barrier to education. COVID-19 has further deprived vulnerable Afghan children from accessing education in Iran, as most classes are online, and students need access to internet and internet-capable devices to be able to attend school. UNHCR data suggest that many Afghan children may not return to schools in Iran after the pandemic (UNHCR 2020c). Financial support and incentives for families are necessary to ensure low-income populations such as Afghans in Iran have equitable access to education.

Currently, Afghans in Iran must study the standard curriculum designed for Iranians, without any additional culturally relevant resources. The self-governed Afghan schools previously filled this gap, but their work was discontinued when the government banned their activities in Iran. Although the majority of Afghans share a similar language and culture with Iranians, there is a need for additional components in the education of Afghan children to avoid forced alienation of refugees from their culture and history. If self-governed schools are not permissible, culturally relevant elements should be considered for different social groups to improve student retention. Teachers should also be trained to provide culturally relevant teaching at Iranian schools.

Investment in the education of Afghans can be considered as investment in the future of Afghanistan and also Iran as a host country. The expectation of the humanitarian organizations and host countries is that Afghans will return home Afghanistan is safe and ready for their return. These organizations and the government of Iran should pay more attention to the long-term impacts of education for Afghans. Access to quality education for Afghans in Iran can contribute to the development of both Iran and Afghanistan in the future.

The current regulations that require Afghan refugees to give up their refugee status and leave the country to return as immigrants with student visas in order to study at Iranian universities creates a massive barrier to higher education for refugees. Between January and March 2020, approximately 200 Afghan refugees returned to Afghanistan, close to 50% of which were students returning with student visas (UNHCR, 2020a). This policy can result in forced family separation for Afghans who must leave their refugee families in Iran once their student visa is expired. Many might be forced to live as under-documented Afghans once their education is completed and their visas are expired just to be able to continue living with their families. A policy needs to be considered by policy-makers in Iran to allow equitable access to higher education for Afghan refugees in Iran.

Refugee populations are at the intersection of several societal states of marginalization, including higher levels of poverty and housing instability. Enacting policies that reduce barriers and enable equitable access to education for refugee populations will contribute to a more just educational infrastructure. A more equitable education system can benefit refugees and host countries in the long term. As a developing country, Iran has been very generous in hosting millions of Afghans for over four decades and providing education for them. International and humanitarian organizations have also been active in building schools and providing financial assistance to Afghans over the years. More sustainable national and international policies and efforts are needed to ensure steady access to quality education for Afghans in Iran.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Biographies

Hamed Seddighi is a Researcher at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. He has been working the last ten years on managing humanitarian services during humanitarian emergencies in the Red Crescent Society of Iran as Deputy for Youth affairs and Deputy for Education & Research. His PhD thesis was about policy analysis and programs evaluation of disaster preparedness programs in Iran. He published several articles on disaster management, pandemics, volunteering in emergencies, humanitarian aid, and humanitarian logistics. In his studies, he focuses mostly on children and vulnerable groups in humanitarian contexts.

Mitra Naseh is an early career migration scholar and an Assistant Professor at Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis. Naseh's scholarship focuses on the social and economic integration of minoritized and racialized groups with a migration background. She also has an interest in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions, specifically cognitive conditions associated with the trauma caused by forced migration. Naseh research is rooted in and guided by her previous professional work experience as a staff member of non-governmental organizations and the United Nations in the Middle East and South Asia.

Maryam Rafieifar is an Assistant Professor in child advocacy at Montclair State University. Her research focuses on the well-being of disenfranchised children and families using community-based participatory methods. Her translational objective is to mitigate the effects of immigration enforcement on trauma among children born to immigrant families through examining and advocating for community-based initiatives. Rafieifar has worked with immigrant communities through her involvement in local and international organizations, including the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

Passion Ilea is a Doctoral student at Portland State University in the U.S. Ilea's research centers on equity, health care, and migration, with an aim to reduce inequity and promote wellness in health care systems at a structural, socioeconomic level.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.