BSACI guidance for the implementation of Palforzia® peanut oral immunotherapy in the United Kingdom: A Delphi consensus study

Paul J. Turner and Nick Makwana joint last authorship.

Abstract

Background

Palforzia® enables the safe and effective desensitisation of children with peanut allergy. The treatment pathway requires multiple visits for dose escalation, up-dosing, monitoring of patients taking maintenance therapy and conversion onto daily real-world peanut consumption. The demand for peanut immunotherapy outstrips current National Health Service (NHS) capacity and requires services to develop a national consensus on how best to offer Palforzia® in a safe and equitable manner. We undertook a Delphi consensus exercise to determine guidance statements for the implementation of Palforzia®-based immunotherapy in the NHS.

Methods

We undertook focus groups with children and young people who had received peanut immunotherapy to assess what was important for them and their carers. Common themes from patients formed the basis of creating draft statements. A panel of 18 multi-disciplinary professionals engaged in two rounds of anonymised voting to adapt the statements and score their importance. A final consensus workshop consolidated any variation in comments and scores to develop the final guidance statements.

Results

The panel achieved consensus on 91% (29/32) of guidance statements, demonstrating strong consensus around pragmatic principles for assuring the integrity of consent, safety and conversion from Palforzia® to real-world peanut products. The greatest amount of feedback was generated from three broad issues; (i) whether eligibility assessment should include compulsory peanut challenges and whether these should be designed to assess the threshold at which patients react to peanut, (ii) the governance processes to best ensure that patients' interests are prioritised and (iii) how to safely transition young people to other services, or discharge them, while they are taking daily peanut.

Conclusions

This consensus highlights the urgent need for the NHS to increase capacity for undertaking diagnostic food challenges as well as developing Palforzia® immunotherapy pathways. The voting panel agreed that families of peanut allergic children should be made aware of immunotherapy, that eligibility assessment should include how co-morbid conditions are managed and that services should monitor for adverse effects. The finalised statements are now published online for clinical practice in the UK. These guidance statements will be adapted in the coming years as more evidence is published and as the international experience of peanut immunotherapy evolves.

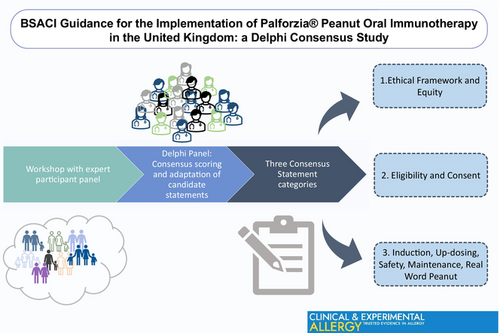

Graphical Abstract

1 BACKGROUND

Approximately 1%–2% of children in the UK have peanut allergy (PA),1-3 which can significantly reduce their quality of life.4, 5 Historically, the mainstay of patient care has been allergen avoidance and education to recognise and treat allergic reactions where needed.6 Peanut Immunotherapy aims to increase the threshold at which individuals are able to tolerate peanut without eliciting an immediate type immune response. Meta-analysis of current peanut immunotherapy studies shows that the oral route currently demonstrates the larger proportion of participants being able to tolerate an increased threshold of peanut.7 The mean maximum tolerated dose of children enrolling for peanut oral immunotherapy (peanut-OIT) was 34 mg and participants in the active arms were six times more likely to tolerate a single dose of 300 mg and 17 times more likely to tolerate 1000 mg of peanut after treatment. As a result, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) now recommends offering peanut-OIT under specialist supervision with evidence-based protocols and licenced pharmaceutical products.8

Studies comparing the safety of undergoing peanut-OIT offer conflicting results. The GA2LEN consortium reported that there was no confirmed increase in adverse reactions (RR 1.1, 1.0–1.2, low certainty) or severe reactions (RR 1.6, 0.7–3.5, low certainty),7 but this was on the basis of number of participants experiencing at least one adverse event, rather than the number of adverse events i.e. patients not on treatment are just as likely to have at least one allergic reaction as patients on peanut-OIT.9 Other analyses have clearly demonstrated that patients receiving peanut-OIT have a higher rate of allergic reactions than those on peanut-avoidance. For example, a 2019 meta-analysis reported that (oral, sublingual or epicutaneous) peanut immunotherapy tripled the risk of anaphylaxis (defined as 2 or more organ system involvement after possible allergen exposure, or isolated hypotension with known allergen exposure; relative risk [RR] 3.1 (1.76–4.72)) and doubled the chance of adrenaline administration (RR 2.72 (1.57–4.72); both high certainty).

Quality of life data from the randomised trials have shown promise, although data is required to assess the impact of peanut-OIT services in practice. Participants and their carers report improved health-related quality-of-life following desensitisation.10, 11 These studies frequently compare quality of life data before and during therapy, rather than between children allocated to the active and placebo arms after their repeat challenges. The greater burden of treatment may be carried by the child who is ingesting daily peanut and is likely to incur adverse effects, which would explain why improvements in the quality of life for the child appear to be less than those of their carers.12 We need to assess how children find peanut-OIT as a treatment offered in the NHS and after long term maintenance therapy.13

In 2022, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommended the use of Palforzia® for desensitising children and young people with PA in the National Health System (NHS), the UK's publicly funded health service.14 Palforzia® is a licenced form of peanut-OIT, with the active ingredient being defatted peanut powder. It is taken in escalating doses defined within an incremental dose programme to gradually increase the patients' daily consumption to a maintenance dose of 300 mg per day (approximately 1½ peanuts). It is licenced for children/young people between the ages of 4–17 years with a confirmed diagnosis of PA. Palforzia® has a ~60%–70% rate of successful desensitisation for children/young people who react to ≤100 mg peanut protein (about half a peanut).15 Payment for Palforzia® itself is now funded from the High-Cost Drug Budget,16 however clinical diagnosis, assessment of eligibility, consent, up-dosing visits and the monitoring of patients currently falls within the routine national/local funding arrangements for paediatric allergy provision. NICE did not consider the resources required to swap patients taking maintenance Palforzia® onto consuming a daily peanut (or equivalent) for the rest of their life or what ongoing monitoring and support may be necessary. There is a need to ensure adequate health service infrastructure, training for staff and dissemination of best practice to optimise outcomes for patients with PA in the NHS.17

2 OBJECTIVES

This Delphi exercise was designed to achieve a consensus guidance to inform and support healthcare professionals (HCPs) in the equitable and safe implementation of Palforzia® desensitisation and ongoing real-world peanut dosing.

Our focus was to enquire and gain understanding about the experience of patients who have received peanut-OIT to address how service design, patient assessment, management and monitoring can be optimised to ensure safety, equity of access and optimal outcomes within the NHS.

This guidance does not address a repeated review of the evidence-base for peanut-OIT nor was our aim to develop detailed guidance for the administration of OIT since other guidelines exist.18, 19 We are addressing the use of Palforzia® for oral desensitisation to peanut and conversion onto real-world peanut dosing. We refer to the whole of this desensitisation pathway, including Palforzia® and ongoing real-world peanut daily dosing, as Palforzia®-based peanut-OIT.

3 METHODS

Prospective panel members were invited through open invitation from the Paediatric Allergy Committee of the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI), ensuring representation from both allergy specialists including specialist nurses, clinical academics, adult immunologists and general practitioners (GPs). The requirement for declaring conflicts of interest was raised at the welcome meeting, consensus workshop and requested from voting panel members for each round.

Separately, children/young people and their families who had undergone peanut-OIT (including with Palforzia®) in clinical studies were invited to attend online focus groups. Open discussion prompts were designed (by SB, PJT, NP). Focus groups were approximately 1 h long, with a maximum of four young people in any one session and offered young people the opportunity to give feedback separately from their parents where age-appropriate. Common themes and salient experiences were distilled and shared with prospective panel members. The candidate statements were then curated by four of the lead authors (NM, PT, DV and TM) who did not vote during the Delphi process.

The predefined structure of the Delphi governed that two rounds of voting would be undertaken using the remote electronic questionnaire platform Qualtrics, eliciting panel members' wish for candidate statements to be made ‘critical’ (Likert score 7–9) or ‘important’ (Likert score 4–6) or ‘not important’ (Likert score 1–3) with consensus criteria as listed in Table S1.20 The panel would have at least 14 participants, and at least 70% voting in either category would be required to achieve consensus. Panel members were asked to declare current conflicts of interest at each round, to allow this Delphi consensus to best align with the Cochrane Conflicts of Interest policy framework.21 All comments from Round 1 were anonymised and shared to panel members prior to Round 2, with a summary median score for each candidate statement and the panel member's preceding Round 1 score. Where Round 2 scores indicated less consensus in scoring responses of a disparity of comments, a final consensus workshop was held with voting to determine whether to reject the statement. The final statements were shared with internal BSACI committees to raise broader clinical implementation points (e.g. Adult Allergy, Standards of Care, Young Person Transition and Equality and Diversity Committees).

4 RESULTS

Eleven participants (aged 10–22 years) who completed boiled oral peanut or Palforzia® immunotherapy within the preceding 6 years participated in online workshops together with 22 parents. In addition, three families of children who had discontinued treatment were interviewed separately. The resulting messages and experiences from these eight workshops were used to inform 31 candidate statements (curated by NM, PT, DV and TM) for voting (see Supplement).

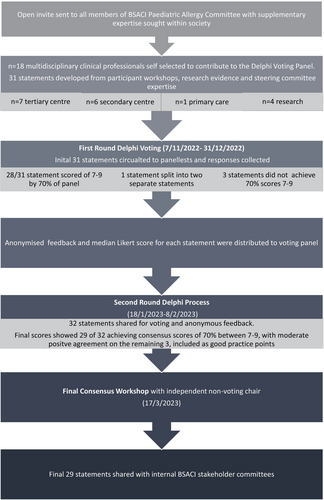

The Delphi panel consisted of 18 professionals (EM, KK, RB, SK, HS, AR, PM, SLeech, HAB, DC, LJM, SB, MVO, SLudman, JD, GS, NP and GR), including 3 specialist allergy nurses, 1 adult immunologist, 1 academic GP, 1 paediatric allergy dietitian, 2 clinical academics, 1 trainee and 8 paediatric allergists. Seven panel members were from tertiary centres, 6 from secondary centres, 1 from primary care and 4 from research teams. Members represented 11 NHS centres, of which 2 were providing Palforzia® to NHS patients at the time of the final consensus workshop. First, last and corresponding authors have not received payments from manufacturer or distribution companies of Palforzia®. Three voting panel members received honoraria and travel support for peanut immunotherapy education or consultancy. One author was principle investigator and three authors were sub-investigators on Aimmune sponsored trials. Two thirds of authors have no relevant ties. The first Round was disseminated on 7th November 2022 and ran until 31st December 2022. All 18 panel members also voted in the second Round administered from 18th January to 8th February 2023 (Figure 1).

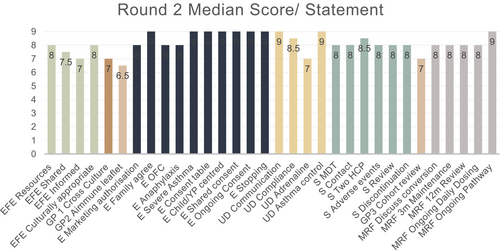

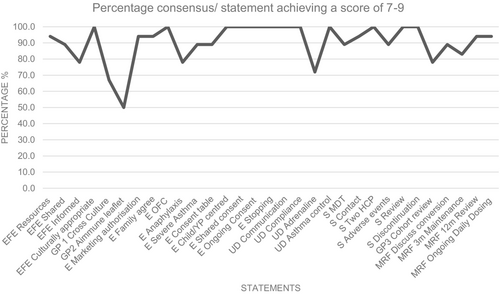

In Round 1, 28 of 31 statements received scores of 7–9 for importance from over 70% of the voting panel and one statement was split into two parts. The final 29 statements all achieved greater than 70% consensus scores of 7–9 following Round 2 of voting (Figures 2 and 3). Four statements received 6 or more comments from panel members and were discussed further in the consensus workshop, which was chaired by a non-voting paediatric immunologist without any conflicts of interest on 17th March 2023. Areas of inconsistency between statements were addressed.

- Ethical framework and equity;

- Eligibility and consent;

- Induction, up-dosing, safety and monitoring;

- Maintenance Treatment, conversion to real-world peanut and follow-up.

4.1 Ethical framework and equity principles for delivering peanut oral immunotherapy

The UK has limited paediatric allergy capacity, with 58% (85/146) of paediatric allergy services offering only up to 10 new appointments and 50% (70/139) offering up to 2 drug/food challenges per week.22 The demand for Palforzia® is outstripping capacity for its delivery and is likely to result in inequitable access.

Shared decision making principles emphasises that the patients' own experiences of PA, its management burden and risk considerations should be the primary drivers behind agreeing to offer OIT to patients.23 The clinical team must ensure that the child/young person is consistently the focus of treatment throughout, to ensure that the balance of lifestyle limitations and risks of reaction remain in favour of continuing treatment.

Clinical capacity should not constrain access to this treatment, and yet new evidence-based treatments are more likely to be adopted in tertiary centres with greater capacity for developing specialist clinical services. The limitation in UK paediatric allergy services is leading to marked geographic variation in access. Ideally, resources should be allocated based on an individual need-based principle.24 Multi-disciplinary teams should orientate peanut-OIT pathways towards understanding the multiple needs of all their patients with peanut allergy. Patient-centred pathways will enhance shared decision making rather than HCPs choosing which families should be offered peanut-OIT (Table 1).25 Wider points relating to shared-decision-making and equity are considered in the discussion.

|

|

|

|

4.1.1 Additional key points from the panel

Given current capacity concerns, services need to expand to ensure that families will receive safe and consistent care. Running a Palforzia®-based OIT service requires significantly more clinical time. There is a risk that providing a Palforzia®-based OIT service may impact upon other families' access to appointments and food challenges. Following NICE approval and the adoption of Palforzia® into the High-Cost Drug Budget, any additional OIT-specific capacity or infrastructure may be considered an essential part of paediatric allergy service delivery from a commissioning perspective (see Table S2 for negotiating points). Monitoring this demand may encourage commissioners to provide additional resource for peanut-OIT. One strategy may be to centralise capacity in a smaller number of regional specialist units.23, 24

4.2 Eligibility and consent

4.2.1 Eligibility

Assessing eligibility is a crucial part of assuring effective and safe treatment, while maximising available capacity for treatment. The evidence base for patient selection is derived from the clinical trials which have informed the approval of Palforzia®. Of note, these studies recruited peanut-allergic children who confirmed eligibility by experiencing objective symptoms below 100 and 300 mg peanut protein at double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge. Following treatment, the majority of participants were able to tolerate a dose of peanut greater than the target maintenance dose of 300 mg peanut protein.

Arguably, it is not appropriate to offer Palforzia® to individuals who are already able to tolerate a reasonable dose of peanut and oral peanut challenge may be presumed necessary to confirm reaction at a low dose before confirming eligibility for Palforzia®-based peanut-OIT on the NHS.26 On the other hand, the stability of peanut reaction thresholds are currently unknown and co-factors (such as intercurrent viral infection, exercise or stress) can influence the dose at which individuals react27, 28; this may also contribute to unexpected reactions to a previously tolerated dose during peanut-OIT.10 Undergoing an oral peanut challenge carries a risk of allergic reaction including anaphylaxis, especially if performed in patients with high levels of sensitisation. However, family focus participants reported clear benefits in undergoing food challenge prior to and after peanut-OIT. They gained confidence in their management of peanut allergic reactions and this step alone appeared to enhance quality of life. This is consistent with the literature.29, 30 In the focus groups, all participants (including parents) were in favour of undertaking peanut challenges before treatment. They would have wanted immunotherapy even if they had reacted to a higher dose of peanut than would have rendered them eligible for the trial. Both participants with PA alone and those with other food allergies were keen to undertake peanut-OIT (Tables 2).

| Eligibility statements |

|

|

|

|

|

| Consent statements |

|

|

|

|

|

Additional key points from the panel

There was widespread consensus that an oral peanut challenge should be used to confirm the diagnosis of PA in most cases. Some panel members felt that a food challenge should be mandatory, since demonstrating an increase in the eliciting dose for peanut with treatment is likely to raise both patient and parents' health-related quality-of-life. Four voting panel members stated that these challenges should be designed to discriminate the lowest observed adverse effect threshold for each patient, allowing treatment to be rationed towards patients reacting to little peanut and avoid the treatment of those who tolerate more than 300 mg. Other panel members felt that making a food challenge mandatory prior to treatment might restrict access to Palforzia® due to limited capacity for food challenges and may incur unnecessary risk for patients. Notwithstanding, clear consensus showed (89% (16/18) voting 7–9 in Round 1; 100% (18/18) in Round 2) that performing a peanut challenge should be a routine part of ensuring appropriate eligibility for Palforzia®.

The panel commented that there is a lack of evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of Palforzia® among children with severe asthma and/or recent life-threatening anaphylaxis. Given this evidence gap, the panel aligned with the Marketing Authorisation recommendations (Table S2). Panel members questioned whether anaphylaxis to a non-peanut food was relevant as an exclusion criterion. Irrespective, it was considered that the stipulation to delay treatment by up to 60 days would not be a significant barrier to treatment. Furthermore, this would equally apply in the very rare case of a patient experiencing a severe anaphylaxis reaction (hypoxia, hypotension, neurological compromise) at a peanut challenge prior to commencing treatment.

4.2.2 Consent

Participants in the focus groups reported that up-dosing required considerable changes to the family routine, with parents reporting ‘putting aside six months to prioritise their child's successful up-dosing’. This impacted on undertaking sport and other extra-curricular activities, travel and holidays, examinations and family activities.

The consent for peanut-OIT must consider the balance of risks and benefits for the patient themselves, while involving their parents and other family members (Table S3). These should be documented and families must be allowed time to reflect before deciding whether to commence treatment and revisited during up-dosing and maintenance phases.

Additional key points from the panel

Panel members recommended that HCPs should allow for the consent process to last longer than a single consultation and be viewed as an ongoing process for all ages of children and young people.

4.3 Induction, up-dosing, safety and monitoring

4.3.1 Induction and up-dosing

Adherence to daily dosing and appropriate Palforzia® dose adjustments in case of asthma exacerbation or illness are crucial points for ensuring the safety of peanut-OIT (Table 3). The families interviewed for the focus groups reported that they had access to a 24-h emergency helpline during treatment. This was particularly helpful in one participant who experienced repeated treatment-related symptoms. Parents reported that they found the helpline reassuring and some felt they were less likely to need to attend the Emergency Department as a result. However, all families would have been keen to access immunotherapy if the clinical team had offered an email address or a helpline which was only in operation during office hours. Most families rarely used the 24-h helpline and the voting panel felt it was not a fundamental part of ensuring safe clinical care. As a more practical alternative, close contact with the supervising team should be facilitated, to promote next-working-day access for advice. This should continue to be available even after maintenance treatment has long been established.

| Induction and up-dosing |

|

|

|

|

| Safety and monitoring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.3.2 Safety and monitoring

Safe implementation of Palforzia® requires consideration of individual patients, broader service infrastructure and the national service-provision level.18 Patients rely on consistency of practice and seamless communication within the multi-disciplinary team delivering peanut-OIT, which should be incorporated into the patient pathway. Contemporaneous and accessible documentation is essential from initial conversations about the benefits and risks of OIT, to informed consent, dose initiation, up-dosing and maintenance and the reporting of any issues relating to treatment-related adverse events, adherence or control of comorbidities. At least two clinical HCPs should be responsible for the provision of Palforzia®, ideally including medical, nursing and dietetic colleagues. This multidisciplinary approach may enhance governance, as well as ensuring continuity of care due to rostering issues. Additional staff are needed for prescribing, dispensing, dose administration and communication regarding appointments and reviews. At a national level, Palforzia® has been assigned a black triangle for monitoring of a new drug and the Yellow Card service enables national monitoring.

The focus groups provided insights into the issues caused by patients who were unable to tolerate peanut-OIT. This included the perception of having ‘failed’, although often this went together with a relief from the burden of treatment which was causing treatment-related adverse events and curtailing their family's lifestyle. All three families who discussed the impact of coming off treatment recommended that a debrief session was important to re-enforce the positive aspects of having trialled therapy, gaining knowledge of how to manage allergic reactions and having a positive mindset for the future in terms of managing their PA.

Additional key points from the panel

It is important that communication is led by staff who manage local Palforzia® pathways for patient safety. Despite regional differences in practice for the prescription of adrenaline, it is important that patients undergoing peanut-OIT can access two unexpired devices at all times due to the risk of anaphylaxis. Good asthma control is essential in patients on peanut-OIT and exacerbations may require dose modifications (or temporary dose cessation) which should be managed by the supervising team.

4.4 Maintenance therapy, conversion to real-world peanut and follow-up

4.4.1 Maintenance and conversion to real-world peanut

The up-dosing regimen lasts a minimum of 22 weeks, whereby patients proceed onto a daily maintenance dose of 300 mg of peanut protein (Table 4). Participants in the focus groups unanimously favoured coming off the medicalised peanut preparation in favour of consuming commercially available peanut products to maintain desensitisation. The children reported that they preferred ‘real-world peanut’ because they could see what progress they had made and it made the process feel ‘normal’.

|

|

|

|

|

Peanut desensitisation with Palforzia® was demonstrated in the Palisade study (with primary outcome double-blind peanut challenge after 6 months of daily maintenance dosing) and in the Artemis study (with peanut challenge after 3 months of daily maintenance dosing). No evidence has proven desensitisation within a shorter period of attaining maintenance and so 3 months of daily maintenance has been considered the minimum recommended period. Twice weekly dosing was associated with significantly less effective desensitisation than continuing daily maintenance dosing over 2 years of the Palforzia® follow-up.31 No evidence has been published which compares daily dosing to other regimens when undertaking peanut-OIT with ‘real-world’ peanut products.

Additional key points from the panel

Panel members felt that the duration and frequency of clinical monitoring while on maintenance and the timing for conversion onto real-world peanut should be planned according to the patient's individual needs and history of adverse effects during Palforzia® treatment. All HCPs involved in the patient's care should signpost and pre-emptively plan with young people access to support for their peanut-OIT management as they grow up. This may involve continued advisory support through paediatric services, transition pathways, adult allergy services, their GP and/or further-education affiliated health services according to what is accessible. Services initiating Palforzia® should consider the implications of starting peanut-OIT within different age-groups of patients, especially in relation to transition to adult services.

5 DISCUSSION

This is the first Delphi driven consensus study to support the aim to deliver of Palforzia® equitably and safety within the UK National Health System. This Delphi process showed that the ethical implementation of Palforzia® within the NHS requires urgent investment in diagnostic oral food challenge capacity, as well as the staff, clinical space, time and governance structures to support the implementation of peanut-immunotherapy services themselves. The voting panel decided that families with peanut allergic children should be made aware of peanut immunotherapy and consent be based on Shared-Decision Making. Eligibility assessment should include a presumption to arrange a peanut challenge as well as assessment of comorbid allergic disease. While offering a 24-h telephone service was not felt to be essential, offering timely responses to queries within 72 h and reviewing patients in the light of adverse effects was adopted as a recommendation. Services must offer a multidisciplinary approach and ensure follow-up for patients after establishing maintenance therapy. The panel highlighted that there is a lack of evidence regarding best practice for swapping onto real-world peanut and that adolescents may need more flexible care pathways to support their ongoing daily dosing of peanut.

We started by assessing participants' experience of undergoing peanut-immunotherapy in online workshops to develop the candidate statements. Three of 11 of these children had taken Palforzia® itself before NICE had approved it as a funded treatment. We could have interviewed additional people from families who had refused peanut-OIT research participation.

We engaged a wide range of HCPs from different regions across England and from different tiers within the health system while complying with Cochrane-recommended standards for conflicts of interest, to develop guidance statements at the stage when Palforzia® is being adopted within the NHS.

We identified clinically pertinent topics that are relevant for the clinical implementation of Palforzia®-based OIT which may be useful when considering its adoption in government-funded, resource-limited settings (Table S5).

Shared decision making is a key principle for delivering peanut-OIT,32 although themes for ensuring cultural competence and equity are less well developed in this arena. Parents prefer formally trained practitioners to support their child's care and will consider longer waiting times and remotely-facilitated appointments to secure this quality of support.33 This may be especially relevant when considering how paediatric allergy services may develop culturally competent shared decision making and where decisional conflict occurs within the family (Table 5).

| Domain | Healthcare barriers | Development goals | Discussion topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation and engagement |

Implicit bias of professionals Team members must offer support for the treatment of co-morbid conditions, which otherwise may limit access to therapy. They should signpost peanut-OIT as a treatment option |

Training and management Managing implicit bias and prioritising the reduction of discrimination towards patients, families and among professionals Reduction of ‘fear of missing out’ as a primary motivator for families Appreciation that child's opinion may vary extensively from their parents |

Goals of therapy What are the most important goals of peanut-OIT: social meals, facilitating travel, reducing anxiety Health beliefs How do family appreciate their child's susceptibility to reactions, severity of reactions and role of desensitisation? Discussing bullying, stigma and the relative impact of peanut-OIT Ask about the impact of asking about food ingredients, having food reactions, need for medication, safety and other food allergies |

| Consent |

Decision-making patterns Understanding how families usually make health-care decisions |

Decision and adherence Asking how families make healthcare decisions and involving their child. Who may best ensure adherence to medication? |

Asking about expectations for peanut-OIT Specific lifestyle considerations Dietary choices, fasting |

| Understanding |

Language barrier Time and support required |

Increase time or choice of professionals available. Collaborate to develop materials in plain English, different languages and audio with transcripts | |

| Risk | Reluctance to offer treatment |

Reducing defensive decision-making Increased support may be required to ensure treatment of co-morbid conditions and food allergy desensitisation |

Uncertainty How comfortable are family with uncertainty? Health-seeking behaviour Ask about prior experience with GP, A&E and allergy team |

| Cultural impact |

Cultural insight Discussing benefits and challenges for children of non-white ancestry |

Fostering discussion between staff and departments about cultural impact of peanut-OIT |

Wider cultural support or influence Understanding support from wider family and cultural groups |

| Socio-economic impact | Relative socio-economic impact | Ask families about potential impact on earnings and difficulties with time off school and regular travel |

We did not seek to specify the clinical infrastructure needed to support peanut-OIT, nor the competence-based requirements for HCPs involved. These have been addressed elsewhere in the literature.18 Developing a service to deliver OIT will require training which should be tailored to existing clinical skills.

The safety of Palforzia® in clinical practice will be an important outcome measure of efficacy. We were not able to consider best practice for conversion from Palforzia® to taking daily real-world peanut doses nor the longer-term management of peanut-OIT currently, because there is little evidence or practical knowledge regarding these phases of treatment in the real-world setting. Any national assessment of the safety of Palforzia® would need to adhere to standardised definitions for treatment-related adverse events and consider how to consider the potential impact of co-factors. The BRIT Immunotherapy Registry has the facility to record the initiation of Palforzia® and record quality of life outcomes, although patients cannot yet enter this data online themselves. Currently, clinical teams need to instigate locally appropriate governance processes, invite the advice from external professionals (e.g. through the BSACI) and report through the national Yellow Card system for reporting pharmacological adverse events if required. It will not be possible to discriminate between centres developing outstanding practice and those who are struggling to deliver optimal care at the current time.

On a national basis, the commissioning of Specialised Services for Paediatric Allergy within the NHS outlines that both aeroallergen and food immunotherapy should be offered at a tertiary level. However, the prevalence of PA among children and the demand for Palforzia®-based immunotherapy is vastly outstripping the capacity of paediatric allergy services. Data from the POSIDON trial suggested that pre-school children between 1 and 3 years of age were able to benefit from Palforzia® desensitisation.34 It is therefore possible that there will be an extension of licensing towards younger children, since 61% of children from 1 to 3 years of age tolerated 2000 mg of peanut in the exit challenge while taking daily maintenance, which compares favourably with the 67% of 4–17 year olds, who tolerated 600 mg on challenge.15, 34 The prevalence of PA and inequity of access to Palforzia® demonstrates an urgent need to increase the availability of day-case beds, design clinical templates for running Palforzia® up-dosing alongside other clinical visits, increase specialist staffing and access to training to enable provision at a national level. Strategically, there is good rationale for consider formalising the relationships between paediatric allergy units within a given region in order to deliver peanut-OIT. There may be capacity to administer a higher proportion of peanut challenges and dose escalation at larger regional centres, before patients receive later up-dosing visits at their regional centre. These considerations were outside the scope of this current Delphi exercise.22

We used patient focus groups and an anonymised Delphi consensus process to produce guidance statements aiming to implement the use of Palforzia® safely and equitably in the NHS. The voting panel demonstrated that the insufficiency of food challenge resources, as well as the lack of staff time and clinical space to undertake the implementation of Palforzia® immunotherapy is abruptly limiting its roll-out. The process demonstrated strong consensus around consent practices, safety and prompt conversion to real-world peanut. The voting panel showed that there is a need to define best clinical practice when considering how to equitably assess patients eligibility, promote appropriate governance processes and support wider NHS services in supporting peanut-OIT management. Significant research priorities were identified, such as the development of assays to assess the threshold at which patients show reactivity to peanut and the best management practice of children with a history of severe asthma, recent and refractory anaphylaxis. We will continue to monitor the experience of peanut-OIT through the UK and aim to undertake a reappraisal of these guidance statements in the event of significant developments.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TM, NP, PT and NM designed the study. Workshops designed by NP, DB, PT and undertaken by NP, DB, PT, NM, DV and TM. Voting panel NP, SB, AR, EM, SLeech, DC, JD, SLudman, GR, LM, HB, SK, RB, PM, FS, HS, KK and MC-O. Manuscript drafted by TM, NM and PT, with review and editing by remaining co-authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr Scott Hackett – Birmingham Heartlands, Bordesley Green East, Birmingham, B9 5ST.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

GRoberts has received consultant fees from ALK-Abello, Viatris, DBV and AstraZeneca. SLeech, KK and RB have received speaker fees and honoraria from Aimmune. SLeech has received consultancy from Aimmune. PT was PI for Aimmune trials.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.