Review article: Translating STRIDE-II into clinical reality – Opportunities and challenges

The Handling Editor for this article was Professor Richard Gearry, and this uncommissioned review was accepted for publication after full peer-review.

Summary

Background

With the introduction of novel therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), ‘treat-to-target’ strategies are increasingly discussed to improve short- and long-term outcomes in patients with IBD.

Aim

To discuss opportunities and challenges of a treat-to-target approach in light of the current ‘Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease’ (STRIDE-II) consensus

Methods

The 2021 update of STRIDE-II encompasses 13 evidence- and consensus-based recommendations for treat-to-target strategies in adults and children with IBD. We highlight the potential implications and limitations of these recommendations for clinical practice.

Results

STRIDE-II provides valuable guidance for personalised IBD management. It reflects scientific progress as well as increased evidence of improved outcomes when more ambitious treatment goals such as mucosal healing are achieved.

Conclusions

Prospective studies, objective criteria for risk stratification, and better predictors of therapeutic response are needed to potentially render ‘treating to target’ more effective in the future.

1 THERAPEUTIC TARGETS IN IBD: THE TREAT-TO-TARGET CONCEPT

Chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are immune-mediated inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract that are frequently accompanied by extraintestinal manifestations.1 The pathogenesis of IBD is extremely complex and multifactorial and has not been conclusively elucidated to date. However, based on a better understanding of the pathophysiology of IBD, numerous new therapeutic approaches have emerged in recent years, ranging from innovative biologic agents to targeted small molecules. This has been accompanied by an evolution of treatment goals and also discussion about new treatment strategies.

Whereas in the pre-biologics era treatment goals were limited to predominantly symptomatic control, steroid sparing and prevention of surgery, the focus today has extended to ambitious patient-centred parameters (e.g. quality of life, prevention of disabilities and work productivity) as well as objective markers of disease control like mucosal, histological or transmural healing and ultimately reduced hospitalisations, surgeries and invalidity. It has become evident in recent years that these ambitious treatment goals cannot be simply achieved with new medical treatment options, but more complex strategies including new treatment algorithms in addition to new drugs may be needed. Some of these new treatment algorithms include top-down approaches, early intervention, tight monitoring, treat-to-target strategies or combination treatment. Most of these strategies have been successfully employed in other chronic diseases like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis and various oncological disorders.

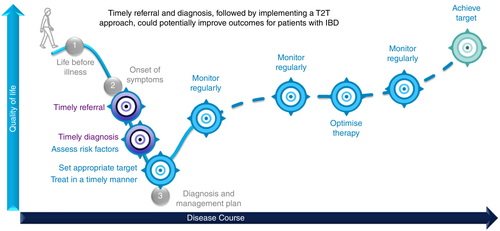

The ‘treat-to-target’ approach is characterised by a pre-specified realistic therapeutic target that should be achieved in a predefined timeframe (Figure 1). For this purpose, patients are monitored regularly after the initiation of therapy (‘tight control’). Today, objective indicators of inflammation such as biomarkers and endoscopic findings allow gastroenterologists to evaluate the response independently of the patient's subjective perception. This is very important as symptoms and inflammatory activity do not correlate adequately in all patients, and the latter may be responsible for worsening of disease.2

If targets are not achieved within the predefined timeframe, the therapy should be re-evaluated and ideally modified, discontinued or switched. If the target has been achieved, dose adaptations of medications or discontinuation of certain drugs, for example, steroids, should be considered as well. This concept is based on the hypothesis that active therapeutic management using disease-modifying drugs (DMDs or disease-modifying anti-IBD drugs, DMAIDs) has a positive influence on the natural course of the disease in the long term.3

2 STRIDE RECOMMENDATIONS: PREDEFINED TREATMENT TARGETS IN IBD

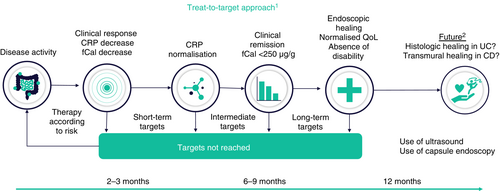

Formulating uniform treatment targets for highly complex diseases such as IBD is not an easy task, therefore simplifying and generalising may be unavoidable to a certain extent. In 2015, an expert panel of the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD) first published recommendations founded upon an evidence-based expert consensus in the form of the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) recommendations, specifying predefined treatment goals for adult patients with IBD in a treat-to-target concept.4 The updated STRIDE recommendations (STRIDE-II, published 2021) aim to best address the complexity of IBD and their multidimensional influence on the diverse aspects of the lives of affected patients including, for the first time, children and adolescents with IBD. STRIDE-II considers not only the classic IBD symptoms such as increased stool frequency, abdominal pain and rectal bleeding but also takes into account restoring and maintaining quality of life as a formal treatment goal (Figure 2).

The most important addition of STRIDE-II is the definition of time-dependent treatment targets – short term, intermediate and long term – as well as the introduction of drug-specific time points, suggesting when specific targets should be achieved. This approach tries to reflect the variable onset of action of different treatment modalities based on clinical experience and may support appropriate modifications of the therapeutic approach. It is important to note that treatments are not only often continued in the absence of adequate efficacy but also are frequently terminated too early, as effects may not yet be evident. It should be emphasised, however, that time-dependent targets are not meant to be seen as permanent and independent, depending on the individual patient. A patient with multiple therapeutic failures and last-line or experimental treatment will need a different approach than a patient with inadequate response to first-line treatment. Furthermore, there will be different approaches needed in elderly or paediatric patients as well as in patients with pre-existing or ongoing comorbidities, adverse events to previous treatments or extraintestinal manifestations. Since improving or maintaining good quality of life can be seen both as a short-term target as well as a long-term goal, the balance between efficacy and therapy-related adverse events must also be considered.

At this point, it is important to have a common understanding of the terminology. While STRIDE-II does not differentiate between the terms target and goal, we propose that a target is a short-term ambition that will impact the outcome if achieved, and as such it is modifiable with therapeutic optimisation. In contrast, a goal should be defined by physician and patient, reflecting the long-term ambition that can be achieved, when individual targets are met,6-9 see Table 1. We suggest that reaching one or multiple therapeutic targets as recommended in STRIDE-II can be a means to achieve an overarching goal such as being able to work again on a regular basis or to have a normal social and sexual life. Strikingly, IOIBD experts agreed in the SPIRIT consensus that ‘the ultimate therapeutic goal in both CD and UC is to prevent disease impact on patient's life […], midterm […] and long-term complications’.6

| Endpoint10 | Target11 | Goal5 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Current IBD therapy aims to achieve a noticeable reduction in symptoms in the short term, clinical remission and normalisation of biomarkers in the intermediate term, and in the long term, it should ensure normal quality of life and a return to normal activities of daily living in addition to mucosal healing. For children, normal growth has been introduced. Histological and transmural healing were not defined as formal treatment targets by the STRIDE-II group because there was not enough evidence suggesting that these endpoints are significant enough to justify an increased utilisation of medical treatment.5 For additional treatment goals, STRIDE-II also recommends specific criteria and thresholds for evaluating the therapeutic outcome. Understandably, these criteria are not all validated by controlled studies but their definition by a high-level expert panel in a rigid consensus procedure can be considered robust. Briefly, the STRIDE-II recommendations are based on a comprehensive systematic literature review as well as surveys sent to IOIBD members asking them to name the most important targets in UC and CD separately which were then ranked by order of importance in several voting processes. Consensus statements were drafted by a steering committee and, finally, voted on by all IOIBD members.5

STRIDE-II provides the treating physician with valuable recommendations for everyday clinical practice. Since publication, the updated recommendations have attracted considerable attention from IBD experts. While the recommendations are generally recognised as an important reference when treating cases of complex and heterogeneous IBD, certain aspects of STRIDE-II are also subject to intensive discussions.

3 STRIDE-II AND TREAT-TO-TARGET: PRESSURE TESTING THE CONCEPTS

STRIDE-II recommendations may be perceived as too ambitious since the current therapeutic armamentarium for IBD patients is still limited with respect to overall efficacy. In clinical practice, only few IBD patients can achieve the long-term goals specified by the STRIDE-II consensus, highlighting the need for new therapeutic modalities, new treatment strategies or treatment algorithms and further studies in the field of IBD. Additionally, it has been suggested that the STRIDE-II recommendations do not live up to the extremely complex and diverse reality of treating IBD patients. While patient care should obviously be individualised when it comes to defining treatment goals, for example, treatment goals in the elderly may be different from goals in paediatric patients, detailed recommendations for specific subgroups are out of scope of the current STRIDE-II consensus. STRIDE recommendations are designed to provide a strategic framework that should facilitate the therapeutic management of patients with IBD, particularly for those physicians less experienced with the ever-increasing number of diagnostic and therapeutic options and endpoints. STRIDE-II should be seen as a guide for improved treatment that reflects current treatment options (evidence) and corresponding expert opinion (eminence). It may be necessary to deviate from these algorithms in certain situations, as the IOIBD expert group has pointed out in their discussion.5 Furthermore, it may be necessary to update the current recommendations at some point in the future according to new emerging evidence which could also include modified or entirely new targets – but it is the best guidance gastroenterologists currently have.

Another valid criticism relates to the importance of mucosal healing, which is defined in STRIDE-II as an explicit long-term treatment goal, although at present this is only achievable in a minority of IBD patients. Depending on the definition of mucosal healing and the chosen therapy, this goal has been achieved in <46% of CD patients in various clinical trials,9 as highlighted in Table 2. Additionally, it is reasonable to ask for a common definition of mucosal healing before routinely utilising it as a therapeutic goal and/or prognostic marker: on the one hand to compare outcomes of clinical trials, and on the other hand to use a common language and definitions when developing future therapeutic strategies. However, a common definition of mucosal healing may require joint work of medical societies and a rigid consensus process, as no current guideline by any IBD society or expert consensus has come up with a uniform guideline and definition of mucosal healing in IBD until now. While we currently do not know how extensive mucosal healing must be, we are convinced that using any definition (see Table 2) and trying to achieve this target is better than not pursuing mucosal healing at all. One could argue from an ethical and medical point of view that we should strive for ambitious treatment goals that can have a favourable impact on the natural disease course, even if these goals appear to be out of reach for most patients as of now. Examples can be found in other areas of medicine such as oncology. Rather intensive treatment regimens such as surgery, radiation and chemotherapy are commonly utilised with the intention to cure cancer, even though these measures are (expectedly) not capable of this in many cases and can be linked with adverse events. Still, after thorough benefit–risk evaluation, they are often utilised to give the patient the best odds of survival. This concept could be translated into IBD care as well.

| CD study | Intervention | Time of endoscopy | Definition of MH | MH rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SONIC19 | AZA monotherapy | Week 26 | No mucosal ulcerations | 17.0 |

| AZA + IFX dual therapy | 44.0 | |||

| IFX monotherapy | 30.0 | |||

| ACCENT I20 | Infliximab Q8W | Week 54 | No mucosal ulcerations in previously affected segment | 44.0 |

| Infliximab episodically in case of flare | 18.0 | |||

| EXTEND21 | Adalimumab | Week 12 | No mucosal ulcerations | 27.0 |

| Placebo | 13.0 | |||

| Adalimumab | Week 52 | 24.0 | ||

| Placebo | 0.0 | |||

| MUSIC22 | Certolizumab pegol | Week 10 | CDEIS < 6 | 37.0 |

| Week 54 | 27.0 | |||

| VERSIFY23 | Vedolizumab | Week 26 | SES-CD ≤ 4 | 12.0 |

| Week 52 | 18.0 | |||

| UNITI-1&224 | Ustekinumab | Week 8 | Complete absence of ulcers | 9.0 |

| Placebo | 4.1 | |||

| IM-UNITI24 | Ustekinumab 90 mg Q12W | Week 44 | 12.8 | |

| Ustekinumab 90 mg Q8W | 21.6 | |||

| Placebo | 9.8 |

| UC study | Intervention | Time of endoscopy | Definition of MH | MH rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULTRA 125 | ADA 160/80 mga | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 | 46.9 |

| ADA 80/40 mgb | 37.7 | |||

| Placebo | 41.5 | |||

| ULTRA 226 | ADA | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 | 41.1 |

| Week 52 | 25.0 | |||

| Placebo | Week 8 | 31.7 | ||

| Week 52 | 15.4 | |||

| SELECTION27 | Filgotinib 100 mg | Week 10 (induction) | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 AND no or mild increase in chronic inflammatory infiltrate in lamina propria, no neutrophils in lamina propria or epithelium and no erosion, ulceration or granulation tissue (based on Geboes Scale) | 14.8 (biologic naïve) 6.3 (biologic experienced) |

| Week 58 (maintenance) | 20.9 | |||

| Filgotinib 200 mg | Week 10 (induction) | 23.3 (biologic naïve) 9.9 (biologic experienced) | ||

| Week 58 (maintenance) | 32.7 | |||

| Placebo | Week 10 (induction) | 10.9 (biologic naïve) 4.2 (biologic experienced) | ||

| Week 58 (maintenance) | 13.5 (filgotinib 100 mg during induction) 10.2 (filgotinib 200 mg during induction) | |||

| ACT 128 | Infliximab 5 mg | Weeks 8, 30 and 54 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 | 62.0 (W8), 50.4 (W30), 45.5 (W54) |

| Infliximab 10 mg | 59.0 (W8), 49.2 (W30), 46.7 (W54) | |||

| Placebo | 33.9 (W8), 24.8 (W30), 18.2 (W54) | |||

| ACT228 | Infliximab 5 mg | Weeks 8 and 30 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 | 60.3 (W8), 46.3 (W30) |

| Infliximab 10 mg | 61.7 (W8), 56.7 (W30) | |||

| Placebo | 30.9 (W8), 30.1 (W30) | |||

| TRUE NORTH29 | Ozanimod | Week 10 | Mucosal endoscopy score ≤1 and Geboes score <2.0 | 12.6 |

| Placebo | 3.7 | |||

| Ozanimod | Week 52 | 29.6 | ||

| Placebo | 14.1 | |||

| OCTAVE induction 130 | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore ≤ 1 | 31.3 |

| Placebo | 15.6 | |||

| OCTAVE induction 228 | Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | 28.4 | ||

| Placebo | 11.6 | |||

| OCTAVE maintenance30 | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID | Week 52 | Endoscopy subscore ≤ 1 | 37.4 |

| Tofacitinib 10 mg BID | 45.7 | |||

| Placebo | 13.1 | |||

| GEMINI 131 | Vedolizumab | Week 6 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1 | 40.9 |

| Placebo | 24.8 | |||

| Vedolizumab Q4W | Week 52 | 56.0 | ||

| Vedolizumab Q8W | 51.6 | |||

| Placebo | 19.8 | |||

| VARSITY32 | Vedolizumab | Week 52 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1c | 39.7 |

| Adalimumab | 27.7 | |||

| U-ACHIEVE study 133 | UPA 7.5 mg QD | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1d | 14.9 |

| UPA 15 mg QD | 30.6 | |||

| UPA 30 mg QD | 26.9 | |||

| UPA 45 mg QD | 35.7 | |||

| Placebo | 2.2 | |||

| U-ACHIEVE study 258 | UPA 45 mg QD | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1d | 36.3 |

| Placebo | 7.4 | |||

| U-ACCOMPLISH58 | UPA 45 mg QD | Week 8 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1d | 44 |

| Placebo | 8.3 | |||

| UPA 15 mg QD | Week 52 | Endoscopy subscore 0 or 1d | 48.6 | |

| UPA 30 mg QD | 67.7 | |||

| Placebo | 14.8 |

- Abbreviations: ACT, active ulcerative colitis trials; ADA, adalimumab; AZA, azathioprine; BID, twice daily; CD, Crohn's disease; CDEIS, Crohn's disease endoscopic index of severity; IFX, infliximab; MH, mucosal healing; QD, once daily; Q8W, every 8 weeks; Q12W, every 12 weeks; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn Disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; UPA, upadacitinib; W, week.

- a 160 mg at week 0, 80 mg at week 2 and 40 mg at weeks 4 and 6.

- b 0 mg at week 0 and 40 mg at weeks 2, 4 and 6.

- c Initially listed as criteria for mucosal healing in the study protocol but later defined as ‘endoscopic improvement’.

- d Defined as ‘endoscopic improvement’ in this study.

The current body of evidence clearly shows that UC patients achieving advanced treatment goals including parameters of mucosal healing have a better long-term prognosis compared to patients who do not reach these milestones (e.g. lower risk of clinical relapse, slower disease progression, higher rates of steroid-free remission, fewer hospitalisations and surgeries and avoidance of colectomy12-14). This paradigm also holds true for patients with CD.9 In several studies, the intermediate and long-term outcome was better among CD patients in whom ambitious treatment goals were achieved than those in whom such goals were not achieved.1, 15-17 A meta-analysis of 12 studies in a total of 673 patients with CD also clearly demonstrated that achieving mucosal healing is associated with increased long-term remission rates.18

From a critical point of view, it should be stressed that a causal link between mucosal healing and improved long-term outcomes in IBD patients could be explained by a less severe underlying disease. To clearly address this, a large prospective, controlled study would be needed that investigates the impact of intensifying or switching treatment on the long-term outcome in patients in clinical remission with residual endoscopic activity. Even if this trial is possible, recruiting patients with prolonged disease duration and already apparent structural damage of the gut may impact the study results. Most likely, recruiting patients within the first year after their initial IBD diagnosis could be appropriate, which has been done in the non-interventional IBSEN cohort study.37 Results from this prospective trial showed that patients who achieved mucosal healing within the first year after IBD diagnosis regardless of their treatment have a better long-term outcome with reduced risk of surgeries and colectomies over the next 10 years, hinting at a possible relationship between early mucosal healing and improved long-term outcomes. If mucosal healing is correlating with lower overall disease activity or initial treatment (which did not include biologics at that time) is nevertheless unclear.

Further criticism relates to the results of randomised controlled trials conducted in the past, such as CALM34 and STARDUST,35 that assessed whether a treat-to-target strategy with a tight control algorithm was more successful in achieving endoscopic and clinical outcomes in CD patients than a clinical medical management strategy alone. The STARDUST study yielded no clinical benefits for patients after an early escalation of therapy based on inflammatory biomarkers as well as endoscopic signs of inflammation.40 In the CALM study, the tight control algorithm using clinical symptoms as well as biomarkers led to better clinical and endoscopic outcomes.39 A follow-up analysis of data from the CALM study showed that induction of deep remission in early and moderate-to-severe CD was associated with a lower risk of progression. However, this decreased risk of disease progression was independent of patient management.41 This finding indicates that reaching the target – and not the particular way the patients are managed – is the important factor. While some patients may achieve ambitious treatment goals with conventional management, it seems evident that actively working towards a treatment target may further improve the long-term outcome in IBD patients.

The results of CALM and STARDUST may be, however, confounded and limited. For example, both studies focused on only one specific biologic – adalimumab (±azathioprine) in case of CALM, and ustekinumab in case of STARDUST. A treat-to-target approach leveraging only one primary medication may not be useful, or an assessment of treat-to-target approaches using multiple products may be more relevant. Furthermore, the study design and patient population differed between the two trials. While the median disease duration was ~9 years in STARDUST and more than half of all patients had previously failed one biologic therapy,35 median disease duration in CALM was ~1 year and only biologic- and immunomodulator-naïve patients were recruited.34 Therefore, no clear conclusion can be drawn currently, and further studies are needed to shed light on the feasibility of mucosal healing as both a prognostic factor guiding therapeutic decisions and as a long-term treatment goal in IBD. In addition, clinical trials do not reflect regular clinical practice, where prolonged treatment in those patients with significant responses may result in better long-term outcomes in patients with delayed treatment responses or temporary combination therapy.

4 IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Despite the lack of a common definition of mucosal healing, the Food and Drug Administration (US) and the European Medicines Agency (EU) have recently indicated a requirement for clinical IBD trials to use endoscopic endpoints to assess mucosal inflammation as well as patient-reported outcomes (PRO).48-50 In order to justify a treat-to-target strategy that ultimately focuses on mucosal healing in routine clinical practice too, further studies need to investigate data gaps and challenges that we summarise in Table 3. Firstly, it is not possible to predict if an individual patient would benefit from adjusting, switching or keeping his or her current treatment due to a lack of predictive parameters, especially if the patient is clinically asymptomatic. This is particularly important because switching, intensifying or combining treatments to achieve a stricter treatment goal is always associated with potential risks and there is no guarantee that a clinically asymptomatic patient will maintain clinical remission after therapeutic adjustments to reach a more ambitious target. Patients not responding to conventional treatment may also benefit from surgical intervention as an alternative to an intensified drug regimen, as shown by the LIR!C trial36 and current ECCO guidelines,38, 39 adding another layer of therapeutic decision-making.

| Developing a common definition of the term mucosal healing |

| Showing long-term benefits of mucosal healing and further analysing the risk–benefit-ratio of ‘treating to target’ in randomised, controlled trials (i.e. closing data gaps, especially in UC) |

| Establishing cost- and time-efficient monitoring strategies in day-to-day practice (e.g. intestinal ultrasound ➔ are transmural healing and/or control of intestinal inflammation as seen on sonographic imaging may be even better targets compared to mucosal healing?) |

| Identifying risk factors for patient stratification (e.g. individual strategies for asymptomatic, geriatric, paediatric and/or comorbid patients are needed) |

| Identifying predictors that allow choosing the best first-line option among currently available therapies capable of reaching ambitious treatment targets reliably |

| Researching new therapeutic concepts and updating the STRIDE-II recommendations accordingly, possibly with modified or entirely new targets |

| Improving IBD screening and identifying afflicted patients as early as possible (since early intervention in the window of opportunity is of the essence) |

| Making a treat-to-target approach feasible in countries with limited healthcare resources |

Secondly, the probability of adverse events and long-term complications can change with intensified treatment since every therapy carries a certain risk of substance intolerance or side effects, for example, the risk of an undesired modulation of the immune system, infection or risk of malignancy.40 This is particularly noteworthy when treating older or younger patients because they are generally more susceptible to side effects.41 Especially for younger patients, long-term safety is extremely relevant and, in a geriatric setting, the line between risk and benefit can be thin. Some studies imply that older patients can benefit more from deescalation of therapy than from adding another drug to their medication plan.41, 42 Older and younger patients are also often underrepresented in clinical trials which leads to a lack of safety information in these specific patient groups.43

Thirdly, the efficacy of therapies might decrease over time,44, 45 which – given the still limited number of therapeutic follow-up options available in gastroenterology (as compared to rheumatology) – may prove problematic. Since follow-up periods in interventional trials are limited by design, they do not provide insights into treatment effects on the long-term disease course and associated long-term risks.

Last, but not least, it is still unclear how deep endoscopic remission and how extensive mucosal healing must be to actually improve the clinical outcome. In addition, the definitions of mucosal healing are not standardised as discussed above. Several questions of clinical importance arise in this context: Which severity and extension of the mucosal inflammation is necessary to justify treatment intensification or even a change in an ongoing treatment, and how should the degree of mucosal healing be determined? Is endoscopy always the method of choice? Is normalisation of faecal calprotectin a sufficiently reliable surrogate marker for mucosal healing? Or should transmural or histological healing be the future goal, especially in CD, which can be discontinuous and patchy? What is the positioning of cross-sectional imaging techniques such as MRI or intestinal ultrasound for non-invasive monitoring46? Answering these important questions will be the key to improving the foundation of a treat-to-target approach that the STRIDE-II recommendations already build upon. Therefore, further prospective studies would be desirable and necessary in this regard.

Nevertheless, it remains to be noted in all these open questions: from the very beginning, when selecting the initial therapy, it seems sensible to choose the therapy that has the highest probability of leading to the strictest possible treatment goal, which clearly goes beyond symptomatic improvement. It is widely acknowledged that mucosal healing is at least a surrogate for therapeutic long-term effectiveness, although further studies are needed to evaluate the prognostic importance of achieving this treatment goal. It should be stressed that the latter does not automatically mean, in the reverse conclusion, that mucosal healing is not prognostically relevant as a therapeutic objective.

There is still an ongoing discussion about future therapeutic targets and long-term goals. Should we be satisfied with our current therapeutic achievements that involve symptomatic response in the majority of our IBD patients or should we raise the bar to more ambitious goals? The ultimate goal for all diseases is obviously to cure, but as this does not seem realistic as of now, strict criteria for disease control that may be more or less reachable for a high percentage of patients may be warranted. Rather than seeking easier goals, ways to reach individual treatment goals for as many patients as possible should be explored, even if they seem ambitious from today's perspective. The selection of therapies should be patient specific and risk adjusted (e.g. severity of disease, age, prior therapies, individual risk factors, occurrence of complications, comorbidities, etc.). Personal ambitions of IBD patients should be respected by the treating physician as well. Shared decision-making between patients and physicians has already become a cornerstone of modern medicine. For a treat-to-target strategy to be successful, patients must believe that reaching a (seemingly irrelevant) treatment target such as mucosal healing may be linked to a reduced risk of surgery and an improved quality of life in the long run – outcomes that directly impact their well-being. While certain endpoints or targets such as mucosal healing may seem unimportant from a patients' point of view, this perspective will most likely change when the patient is properly informed of their implications. Thoroughly explaining the potential benefits of ‘treating to target’ can be time consuming but may improve patient adherence. We think this is noteworthy because surveys have unveiled a discrepancy in the perception of IBD burden between patients and gastroenterologists and its consequences for the patients' day-to-day living, underlining the need for communicating to motivate the patient towards a common cause.7, 8

In addition to selecting the most effective therapy in alignment with the patients' personal goals, the timing of therapeutic interventions also plays an important role: it is undisputed that early use of the right therapy in CD patients leads to significantly better treatment results than delayed utilisation after a long disease course. This applies to symptom improvement,47 the probability of achieving the composite endpoint of symptom improvement and mucosal healing48 and the probability of avoiding a complicated course.49 In many CD patients, therefore, timely use of the right therapy could be of major benefit. As for UC, things are a bit more controversial,50, 51 with a recent meta-analysis suggesting little benefit of early biologic treatment in UC.52 On the other hand, Cortesi et al. showed in an economic evaluation (by a Markov analysis, not a cohort study) that a treat-to-target approach could be cost-effective in patients with mild-to-moderate UC and can improve time in clinical remission while reducing the risk of relapse compared to conventional treatment.53

Therefore, reliable predictors of the effectiveness and potential side effects of different treatment approaches for individual patients could be of great importance. Such predictors would also be a good and necessary basis for assessing whether intensification of therapy or a change in therapy would be appropriate for the individual patient. Although this is currently the subject of intensive research, the wide availability for practical use is not expected in the foreseeable future.54 However, recent studies like TRUST BEYOND demonstrate that pursuing ambitious treatment goals does not necessarily lead to increasingly complex investigations. This study examined the prognostic value of a transmural therapeutic response using intestinal ultrasound (IUS) as a non-invasive and established procedure in the follow-up of IBD.55 Other studies (e.g. STARDUST56 in CD and TRUST&UC57 in UC patients) showed that IUS could be a valuable tool to detect early response to treatment in IBD based on objective IUS parameters like bowel wall thickness or vascularisation. As IUS becomes more available around the world, it may develop into an easy-to-perform bedside test to assess the response to therapeutic interventions similar to biomarkers or endoscopy.

Taken together, mucosal healing can at least be seen as a positive factor that increases the likelihood of a favourable long-term outcome while probably transferring an assertive psychological effect on the patient too. On an individual patient level, it can pave the therapeutic and diagnostic pathway: IBD patients who have not reached mucosal healing yet should be closely monitored and treatment intensification should be considered. Once this therapeutic milestone is achieved, follow-up intervals can be extended and treatment may be de-escalated.

5 NEW THERAPIES – NEW GOALS?

To what extent can new, targeted treatments, and combinations thereof, positively influence the future course of disease in selected patients? Targeted therapies under development address stringent endpoints in pivotal studies, such as complete endoscopic or histological healing, or a combination of both. In the recently published phase 3 results with the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib, up to 44% of patients with an average history of more than 8 years of UC achieved relevant endoscopic improvement (Mayo endoscopic subscore ≤1) by week 8.58 In addition, up to 49% of patients had a histological endoscopic mucosal improvement (HEMI) defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1 and Geboes score ≤3.1 at 52 weeks.58

The endoscopic and histological evaluation of the mucosa is therefore of great importance in clinical trials with newer biologics and JAK therapy approaches. It objectively demonstrates the anti-inflammatory potential of novel targeted therapies and thus gives reason to hope that in the future more ambitious treatment goals of prognostic relevance to the long-term disease course can be achieved in a majority of IBD patients. The unanswered questions posed here should be the subject of future prospective studies.

In conclusion, the extension of treatment targets in STRIDE-II reflects medical and scientific progress in recent years and increased evidence of improved outcomes for patients when more ambitious treatment goals are achieved (endoscopic healing, no IBD-related disability and normalised quality of life). Mucosal healing is associated with better long-term outcomes. However, prospective studies are needed to further demonstrate that mucosal healing and fewer complications are indeed a result of treatment-induced endoscopic remission and cannot be attributed to less severe disease. Currently, it remains difficult to assess whether treatment adjustment or a change in treatment is beneficial for the individual patient, especially if the patient is clinically free of symptoms. Clear criteria for stratifying patients and predictors of therapeutic response are needed to potentially render treat-to-target approaches even more effective and purposeful in the future. Despite certain limitations, STRIDE-II provides valuable guidance for personalised therapeutic management in IBD patients. Clearly, it is motivating and rewarding to reach a target for both sides – the patient and the physician. Endoscopic and histologic evaluation of the intestine is gaining increasing importance in clinical studies with newer therapeutic agents as this objectively demonstrates the anti-inflammatory potential of novel targeted therapies and thus gives reason to hope that in the future more ambitious treatment goals of prognostic relevance to the long-term disease course can be achieved.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Axel Dignass: Conceptualization (lead); methodology (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Stefan Rath: Conceptualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Thomas Kleindienst: Conceptualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Andreas Stallmach: Conceptualization (lead); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Fabian Kaiser of Medizinwelten-Services GmbH for editorial assistance, which was funded by AbbVie.

FUNDING INFORMATION

AbbVie contributed to writing, reviewing and approval of the final version. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

AD has received fees for participation in clinical trials, review activities such as data monitoring boards, statistical analysis and endpoint committees from Abivax, AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Dr Falk Foundation, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen and Pfizer; consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Celltrion, Dr Falk Foundation, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche/Genentech, Sandoz/Hexal, Takeda, Tillotts and Vifor Pharma; payment from lectures including service on speakers bureaus from AbbVie, Biogen, CED Service GmbH, Celltrion, Falk Foundation, Ferring, Galapagos, Gilead, High5MD, Janssen, Materia Prima, MedToday, MSD, Pfizer, Streamed-Up, Takeda, Tillotts and Vifor Pharma; and payment for manuscript preparation from Falk Foundation, Takeda, Thieme and UniMed Verlag. AS reports research funding from AbbVie and Celltrion; has received lecture fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, Biogen, Celltrion, Janssen, Falk Foundation, Ferring, MSD, Recordati Pharma, Streamed-Up and Takeda; and consulting fees from AbbVie, Astellas, Amgen, Biogen, CLS Behring, Consal, Galapagos, Hexal, Janssen, MSD, Norgine, Pfizer Pharma, Takeda and Tillots Pharma. SR and TK are employees of AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG and may own AbbVie stock.