Influenza burden, prevention, and treatment in asthma-A scoping review by the EAACI Influenza in asthma task force

[Correction added on 17 July 2018 after first online publication: The article category was incorrect and has been updated in this version]

Abstract

To address uncertainties in the prevention and management of influenza in people with asthma, we performed a scoping review of the published literature on influenza burden; current vaccine recommendations; vaccination coverage; immunogenicity, efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of influenza vaccines; and the benefits of antiviral drugs in people with asthma. We found significant variation in the reported rates of influenza detection in individuals with acute asthma exacerbations making it unclear to what degree influenza causes exacerbations of underlying asthma. The strongest evidence of an association was seen in studies of children. Countries in the European Union currently recommend influenza vaccination of adults with asthma; however, coverage varied between regions. Coverage was lower among children with asthma. Limited data suggest that good seroprotection and seroconversion can be achieved in both children and adults with asthma and that vaccination confers a degree of protection against influenza illness and asthma-related morbidity to children with asthma. There were insufficient data to determine efficacy in adults. Overall, influenza vaccines appeared to be safe for people with asthma. We identify knowledge gaps and make recommendations on future research needs in relation to influenza in patients with asthma.

Abstract

1 INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a heterogeneous chronic inflammatory lung disease characterized by intermittent airflow obstruction and increased reactivity to bronchoconstrictive triggers. Presently, an estimated 300 million people worldwide suffer from asthma.1 In Europe, more than 30 million people are affected, with 6 million suffering severe symptoms and 1.5 million life-threatening attacks.2 Asthma onset and acute asthma exacerbations (AAEs) have been strongly associated with respiratory viral and (to a lesser extent) bacterial infections.3-11

Influenza viruses cause respiratory infections, typically during winter months. Most significant disease is caused by influenza A and B, which may escape immune pressure by undergoing antigenic drift and recombination; such genetic changes lead to new subtypes, which can cause epidemic or pandemic outbreaks.12, 13 Each year, influenza virus infection affects 5%-20% of the global population,14 while annual vaccination greatly contributes to reduce related morbidity and mortality.15 Upon vaccination, coordinated activity of innate and adaptive immune responses leads to generation of short- and long-lived antibody-producing plasma cells and memory B cells. The importance of influenza as a cause of serious illness and AAE is increasingly appreciated.16, 17 Despite uncertainties about their effectiveness, influenza vaccines are widely recommended for those with asthma.18

To address uncertainties over the prevention and management of influenza in patients with asthma, we performed a scoping review and discuss the current knowledge of the burden imposed by influenza on patients with asthma; current vaccine recommendations and vaccination coverage in various regions; the evidence regarding immunogenicity, efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of influenza vaccines; and the possible benefits of antiviral drugs in patients with asthma. We conclude by identifying knowledge gaps and future research needs in relation to influenza in asthma patients.

2 METHODS

We systematically searched relevant published, unpublished, and in-progress original research and systematic reviews that were pertinent to the subject matter of this EAACI Task Force. This involved searching databases of peer-reviewed published literature (Cochrane Library, EMBASE and CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar) and research in progress (ie, http://www.controlled-trials.com/and http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) for the period 2000-2015. In addition, we wrote to a panel of international experts in an attempt to identify additional unpublished or in-progress work. There were no restrictions on language of publication.

We were particularly interested in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on questions relating to the immunogenicity, efficacy, and/or effectiveness of influenza vaccine among patients with asthma, and epidemiological studies relating to the influenza incidence/prevalence and public health burden and safety of influenza vaccine. Systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis were of interest if they focused on any of the questions of interest.

The searches (see Appendix S1) were undertaken and allocated to relevant subgroup leads depending on the focus of the inquiry. Where possible, studies reported in languages other than English were translated. Within subgroups, 2 reviewers independently reviewed the titles and if necessary abstracts of potentially eligible studies to decide on eligibility; disagreements on study eligibility were resolved through discussion among the reviewers. Studies were then—in the specific context of asthma/allergy—categorized by topic area, namely (i) Global burden of influenza; (ii) Influenza vaccination recommendations and coverage; (iii) Immunogenicity of influenza vaccines; (iv) Efficacy of influenza vaccines; (v) Effectiveness of influenza vaccines; (vi) Safety of influenza vaccines; and (vii) Antiviral treatments against influenza. Reports were then scrutinized and interpreted by experts on the subject matter. Any disagreements on issues to do with interpretation were resolved through discussion.

The searches were first conducted in 2014 and then updated in October 2015. The key characteristics and findings of all eligible studies were summarized in data tables and the findings narratively synthesized. These are presented by topic in Table 1.

| Authors, Year | Country | Study period | Type of study | Intervention | Outcome measure | Key finding (absolute number of positive samples) | Population characteristics | Limitations/commentsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section 2a Influenza-attributable healthcare utilization in asthma patients | ||||||||

| Chacon et al., (2015)174 | Guatemala | May 2009-June 2010 | Epidemiological retrospective study | NA | Demographic and clinical characteristics of deaths associated with influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 | History of Asthma in 11% of the 112 dead patients with a preexisting medical condition (7% children <5 y, 11% people aged 5-59, 16% people aged 60 + , and 18% of the 14 dead pregnant or postpartum women) | 183 children and adults aged 0-60 + y. SARI decedents who tested positive for influenza | Study performed in 7 Central America countries |

| Dawood et al., (2014)49 | USA |

2003-2009 (seasonal 2009-2010 (H1N1) |

Epidemiological retrospective, population-based study | NA | Frequency and severity of influenza complications in hospitalized children |

History of asthma in 31% of children hospitalized for seasonal influenza vs. 42% in children hospitalized for influenza A (H1N1). Asthma exacerbation as a complication in 27% of children with influenza A vs. 18% in children with seasonal influenza (overall, 22% of total) |

6769 children and adolescents aged <18 y hospitalized for both seasonal and H1N1 influenza | |

| Hagerman et al., (2015)175 | Switzerland | June 2009-January 2010 | Prospective/retrospective study performed in 11 hospitals | NA | Clinical characteristics of the influenza-hospitalized children | Asthma 12% among the comorbidities of the 126 influenza-hospitalized children | 326 patients aged ≤18 y (189 <5 y; 126 with comorbidities hospitalized in 11 children's hospitals in Switzerland with a positive influenza A/H1N1/09 RT-PCR from a Nasopharyngeal specimen | Study performed in 11 hospitals in Switzerland |

| Jiang et al., (2015)71 | China | December 2008-June 2014 | Epidemiological retrospective study | NA | Clinical characteristics and severe case risk factors for adult inpatient cases of confirmed influenza | Out of the 240 (7.8%) cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza (H1N, pdm2009, and H3N2), asthma was the most important risk factor for severe cases (RR = 15.200, 95% CI: 1.157-199.633) | 240 adults aged ≥15 y consistent with SARI case definition who were monitored by SARI sentinel hospitals in 10 cities in China | Data extrapolated from abstract in English. Study performed in 10 provinces of China |

| Kwon et al., (2014)176 | South Korea | May 2010-April 2011 | Retrospective study | NA | Prevalence of year-round respiratory viral infection in children with LRTI and the relationship between respiratory viral infection and allergen sensitization in exacerbating asthma |

Influenza virus was detected in 7 (25%) of the 28 asthma patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbation. 18 patients with asthma (64.3%) had atopic sensitization. Influenza virus responsible for asthma exacerbations with an OR 11.9 (1.5-90.4) for atopic asthma), 0.9 (0.1-12.3) for nonatopic asthma, 4.0 (1.2-13.8) for asthma in general |

309 children (median age 26 mo) who were hospitalized for acute LRTIs (pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis or asthma) | |

| Park et al., (2013)177 | South Korea | January-December 2009 | Multisite case-control study | NA | Association of asthma status and severity of H1N1 influenza in adults | Of the 91 cases, 12 (13%) and 3 of 54 controls (5%) were asthmatics (P = NS); of those without other comorbidities except asthma, 8 of 56 cases (14%) and 2 of 49 (4%) controls had asthma (P = NS) |

91 cases (47.3 ± 21.1 y) with a positive PCR for H1N1 influenza and were admitted to the ICU or general ward with a diagnosis of H1N1 influenza. 56 controls (45.0 ± 20.6 y) with a positive PCR for H1N1 influenza, but were not admitted to hospitals |

|

| Placzek et al., (2014)178 | USA |

October 2008-April 2009 (seasonal influenza) April 2009-September 2009 (H1N1) |

Epidemiological retrospective study | NA | Association of age and comorbidity on 2008-2009 seasonal influenza and 2009 influenza A (H1N1)-related ICU stay | Asthma was the most prevalent risk factor for hospitalization, occurring in 28% (n = 148) of the pH1N1 population, and 24% (n = 174) of those with seasonal influenza | 1254 children and adults aged <5-64 y with seasonal and H1N1 influenza admitted to an ICU | |

| Stripeli et al., (2015)179 | Greece |

October 2009-February 2010 and January 2011-May 2011 (pH1N1) 2002-2003 and 2004-2005 (influenza A) |

Epidemiological retrospective study | NA | Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of children hospitalized with pH1N1 compared with those of children hospitalized with seasonal influenza A in previous years | Asthma was the most common underlying illness in both cohorts, but it was considerably more prevalent in the seasonal influenza group (19% vs. 7%; P = .048) | 146 children with pH1N1 aged 0-14 y and 138 children with seasonal influenza aged 6 mo-14 y who were hospitalized for both pH1N1 and influenza A | |

| Taha (2014)57 | Saudi Arabia | June 2009-February 2010 | Retrospective cohort study | NA | Characteristics of pregnant women admitted with 2009 H1N1 influenza in a referral maternity hospital | Bronchial asthma was present in 15 (45.5%) of pregnant women admitted with influenza | 33 pregnant women; mean age 27.7 ± 5.6 y | |

| Tam et al., (2014)180 | USA | 2007-2011 | Retrospective population-based study (chart reviews) | NA | Influenza-related hospitalization of adults associated with low census tract, socioeconomic status, and female sex |

Asthma was increasingly prevalent among cases with progressively higher census tract poverty status (16.4% in low poverty vs. 37.7% in high poverty). Females overall and in each age group were more likely to have asthma (overall, 27.6% vs. 16.7%; P < .001) |

1094 hospitalized adults aged 18-65 + y with laboratory-confirmed influenza | |

| Section 2b Influenza-induced acute asthma exacerbations | ||||||||

| Children | ||||||||

| Azevedo et al., (2003)75 | Brazil | ND | Retrospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/culture and IFA | 0.0% (0) | 36 children aged 2-14 y | |

| Thumerelle et al., (2003)83 | France | October 1, 1998-June 30, 1999 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/IFA, serology, or both | 3.6% (3) | 82 inpatients aged 2-16 y | |

| Biscardi et al., (2004)86 | France | January 1, 1999-June 30, 2001 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/culture and IFA | 3.4% (4) | 119 inpatients aged 2-15 y | |

| 0.0% (0) | 51 first episode (initial asthma) | |||||||

| Bueving et al., (2004)81 | Netherlands | 1999-2001 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Inactivated influenza vaccine vs placebo | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/culture, IFA, and RT-PCR | 7.2% (17) | 235 children aged 6-18 y | Low number of IFV-positive samples in first season-compensated by recruitment of higher number of subjects in second season |

| Johnston et al., (2005)79 | Canada | 10-30 September 2001 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/PCR | 0.0% (0) | 52 children aged 5-15 y | |

| Ketsuriani et al., (2007)80 | USA | March 2003-February 2004 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/PCR | 0.0% (0) | 65 children aged 2-17 y | Modest sample size |

| Miller et al., (2008)63 | USA | 2002-2004 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/PCR or culture | 15.5% (38) | 245 outpatients | |

| 3.7% (19) | 513 inpatients aged 6-59 m | |||||||

| Vallet et al., (2009)84 | France | October 1, 2005-November 30, 2007 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/IFA | 2.4% (4) | 166 inpatients aged 2-15 y | |

| Kwon et al., (2013)176 | Korea | April 2010-April 2011 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/RT-PCR | 25.0% (7) | 28 inpatients aged 60 ± 34 mo (mean ± SD) | Modest sample size, selection of the study population, short duration (1 y) of the study, single medical center, and subjects were limited to children with LRTIs severe enough to require hospitalization |

| Mandelcwajg et al., (2010)82 | France | November 2005-March 2009 | Retrospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/IFA | 14.0% (15) | 107 outpatients | |

| 2.6% (6) | 232 inpatients aged 1.5-15 y | |||||||

| Adults | ||||||||

| Wark et al., (2001)72 | Australia/UK | February 2-December 1, 1998 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/RT-PCR, serology, culture, and IFA | 24% (12) | 49 outpatients aged 16-74 y | |

| Simpson et al., (2003)74 | Australia/UK | ND | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/PCR or serology or IFA |

PCR screening: 24.0% (12) Serology screening: 18.4% (9) IFA screening: 2.0% (1) |

49 inpatients aged 16-74 y | |

| Tan et al., (2003)78 | Singapore | ND | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/RT-PCR, dot blot, and DIG-probe hybridization | 20.7% (6) | 29 inpatients aged 42 ± 15 y (mean ± SD) | Uneven sex distribution (prevalence of females in acute asthma group) |

| Iikura et al., (2014)76 | Japan | May 2011-December 2012 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/RT-PCR | 10.0% (5) | 50 inpatients aged 28-92 y | Although 98% of patients had a common cold history preceding their AAE, a pathogen was detected from nasopharyngeal swabs in only 70% of cases. Overall, 15 major viruses and 6 major bacteria were evaluated by multiplex PCR analysis. It is possible that other minor pathogens may be involved in AAE. Other potential reasons for the low yield include inappropriate timing of sampling, lower respiratory tract infections, misinterpretation of allergic rhinitis symptoms, and single testing upon admission |

| Teichtal et al., (1997)77 | Australia | August 1993-July 1994 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/culture and serology | 19.0% (15) | 79 inpatients aged 16-66 y | |

| Atmar et al., (1998)73 | USA | December 6, 1991-May 3, 1994 | Prospective | NA | Laboratory-confirmed IFV/culture, serology, and RT-PCR | 37.9% (11) | 29 inpatients aged 19-50 y | |

| December 9, 1992-May 31, 1993 | Cross-sectional | 9.8% (12) | 122 outpatients aged 17-77 y | |||||

| Section 3a Current influenza vaccine recommendations for people with asthma | ||||||||

| Grohskopf et al., (2014)181 | USA | 2013-2014 | National Recommendations after reviewing literature based on GRADE approach | LAIV and IIV in asthma | Efficacy and safety | Advise that children between 2 and 4 y who have asthma or wheezing in previous 12 mo should not be given LAIV | Adults and children including those with asthma. Population size unavailable | |

| Grohskopf et al., (2015)153 | USA | 2014-2015 | National Recommendations after reviewing literature based on GRADE approach | LAIV and IIV in asthma | Efficacy and safety | - | All adults and children including those with asthma. Population size unavailable | No change from 2014 to 2015 |

| Byington et al., (2014)182 | USA | 2013-2014 | National Recommendations from American Academy of Pediatrics | LAIV and IIV in asthma | Efficacy and safety |

Annual vaccination (trivalent or quadrivalent) recommended for everyone with special effort made toward asthmatics. Asthma present in 26% hospitalized children with confirmed influenza during the 2013-2014 season |

All children aged > 6 mo including those with asthma. Population size unavailable | |

| Section 3b Current influenza vaccine coverage for people with asthma | ||||||||

| Koshio et al., (2014)132 | Japan | September-October 2010 | Questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey | NA | Receipt of H1N1 vaccine and infection status as well as recording of ACT score. |

Incidence of H1N1 pdm09 infection 6.7% (95% CI 5.7-7.6). Vaccine receipt in 63.9% (95% CI 62.1%-65.8%). Infected patients (n = 170) had significantly lower rates of vaccination, were younger, and had experienced more night symptoms and sleep disturbance in the preceding 2 wks |

2555 asthma patients, aged ≥16 y | Good characterization of patients with asthma but no objective definition of influenza infection |

| Pennant et al., (2015)183 | USA | 2009-2015 | Prospective interventional quality improvement study | Physician reminders, patient letters, nurse-driven | Change in vaccination uptake rate | Vaccine receipt improved from 59% to 64% between 2011 and 2014 influenza seasons | 1142 asthma patients in an allergy clinic aged ≥ 13 y (85 declined vaccine) | |

| Gnatiuc et al., (2015)184 | Global (23 countries) | 2008 onward | International cross-sectional survey comparing high-income and low-middle-income countries | Participants with doctor diagnosed asthma underwent reversibility testing with salbutamol | Use of respiratory medicines and uptake of influenza vaccine in preceding 12 mo | Overall influenza vaccination uptake rates: 1.4% in LMIC vs. 28.4% in HIC (P = .0001) | 15,590 adults with asthma and COPD, aged ≥ 40 y (unclear what proportion are asthmatic) |

Rare example of research comparing multiple countries from across the income spectrum The age criteria for the study likely excluded a large proportion of patients with asthma |

| Vernacchio et al., (2014)185 | USA | 2009-2012 | Learning collaborative model | Regular face to face meetings and electronic communication between healthcare teams | Uptake of influenza seasonal vaccination. Uptake of asthma action plans | Inconsistent improvements in rates of vaccine uptake. Significant increase in implementation of asthma action plans | 594 patients with persistent asthma, aged 5-17 y | |

| Blackwell et al., (2015)186 | USA | 2009-2010 | Cross-sectional survey | Telephone survey | Receipt of vaccine in previous 12 mo | Patients with asthma receiving H1N1 vaccine: OR 1.13 (CI 0.97-1.33) | 667 children, aged 4 mo to 17 y, including those with asthma | |

| Aigbogun et al., (2015)187 | Global | 2014 | Systematic review | NA | Uptake of vaccination rates in high-risk children | Reminder letters useful in improving uptake but less evidence for telephone recall | 9 studies in children with asthma, aged 6 mo to 19 y | |

| Mazurek et al., (2014)188 | USA | 2006-2009 | Cross-sectional survey | Telephone survey | Influenza vaccination uptake in the preceding 12 mo | 42.7% uptake rate. Higher rates in those aged 50-64 y, unemployment, and in those requiring urgent treatment for worsening symptoms | 28 809 adults aged 18-64 y with work-related asthma | |

| O'Halloran, (2015)189 | USA | 2012-2013 | Cross-sectional survey | Telephone survey | Influenza vaccination uptake in the preceding 12 mo | Uptake rate of 29% (95% CI 26.5%-31.7%) | 8,831 adults, aged 18-64 y with “pulmonary disease” | |

| Lin et al., (2015)190 | USA | 2010-2013 | Prospective interventional quality improvement study | Utilized the “4 pillars immunization toolkit” | Influenza vaccination rates pre- and postintervention | Uptake rates increased between 2010-2011 and 2012-2013 seasons in non-White children: 46% to 61%; White children: 58%-65%. | 8250 children with asthma aged 6 mo-18 y | This intervention reduced the racial disparity seen in vaccination uptake rates |

| Shoup et al., (2015)191 | USA | 2012-2013 | Pragmatic 3-arm randomized control trial |

Three arms: 1. Postcard reminder 2. Telephone reminder 3. Postcard & telephone reminder |

Change in influenza vaccination rate |

No difference in intervention groups. Telephone (interactive voice response) calls were most cost-effective |

12 285 adults aged 19-64 y with asthma or COPD | |

| Buyuktiryaki et al., (2014)109 | Turkey | 2010 | Cross-sectional survey of parents | Questionnaire | H1N1 and seasonal influenza vaccination rates with analysis of demographic factors, asthma control parameters and parental attitudes toward vaccination |

16.8% received H1N1 vaccine; 45.7% received seasonal vaccine. Significant factors influencing uptake included low educational background of parents, previous vaccination with seasonal influenza and having a family member vaccinated against Influenza A/H1N1. Asthma control parameters had no influence on uptake of the vaccine and physician recommendation (84.8%) was important in the decision-making process for immunization |

625 children and adolescents aged 6-18 y with asthma | |

| Skupin et al., (2015)192 | USA | 2013 | Cross-sectional survey | Questionnaire | Influenza vaccination uptake in preceding year |

Black patients had much lower vaccination rates (62.1%) than White (83.8%) or Asian (93.3%) patients. Belief in efficacy in vaccine and physicians recommendation important determinants in higher vaccination rates |

472 adults attending internal medicine and allergy clinics | |

| Hart et al., (2014)193 | USA | 2013 | Cross-sectional survey | Structured interview | Vaccination uptake in previous year and parental intent to vaccinate in upcoming flu season |

64% (95% CI 59%-70%) received vaccine in previous year. 37% of those parents with intent to vaccinate did not actually do so. |

224 children, aged 6 mo-17 y, attending pediatric emergency department | Unclear what proportion are asthmatic at baseline |

| Lo, (2014)194 | USA | 2013-2014 | Prospective interventional quality improvement study | Implementation of influenza immunization bundle | Vaccination rate pre- and postintervention | Vaccination rate improvement from 19% (6%-26%) to 39% (9%-55%) | 117 children attending hospital with asthma exacerbation | |

| Regan, (2014)195 | Australia | 2013 | Cross-sectional survey of electronic outpatient records | NA | Assessment of proportion of people immunized and estimate of vaccine effectiveness |

29.7% vaccination rate in patients with asthma vs. 52.2% in those with coronary heart disease. In all patients, combined clinical and pathological data suggested vaccination had effectiveness of 56% in preventing infection: OR 0.44 (95% CI 0.24-0.79) |

2731 general practice patients with clinical and pathological data | |

| Section 4 Immunogenicity of influenza vaccines in asthma | ||||||||

| Bae et al., (2013)121 | Korea | 2011-2012 influenza season | Phase 4, multicenter, open-label study | TIV (H1N1, H3N2, B) (7.5 μg per strain). Two doses in vaccine-naïve children; 1 dose in previously vaccinated. Interval between first and second dose not stated | Short-term seroconversion rates, seroprotection rates, GMT, and GMT ratio; HI assay Safety: local and systemic adverse events | Seroconversion and seroprotection rates in wheezers were similar to healthy children and significant for all 3 strains. The GMT was higher in the 1-dose group vs. the 2-dose group both in healthy children and in wheezers. The GMT ratio was significantly higher in healthy children than wheezers for the H1N1, H3N2 strains. No difference between steroid-treated and nontreated wheezers | 68 healthy children and 62 recurrent wheezers aged 6 mo to 3 y |

Chronic and high-dose ICS excluded. No adjustment for ICS dose. Age significantly lower in healthy controls (1-2 y) than in wheezers (2-3 y) |

| Busse et al., (2011)124 | USA | 2009 influenza autumn season | Randomized, open-label study | Monovalent H1N1 tested at 2 doses (15 vs. 30 μg) twice at 21 d interval | Short-term rates and GMT of seroconversion and seroprotection; HI assay and microneutralization |

The 2 dosing groups did not differ in seroconversion rates. In mild-to-moderate asthma, the 2 doses offered equal seroprotection. In severe asthma, seroprotection was significantly higher with the 30 μg dose In patients with severe asthma >60 y old, the seroprotection was achieved only with the 30 μg dose The second dose provided no additional benefit. Atopy, BMI, systemic corticosteroid, or ICS dose had no influence on HI GMTs or on seroprotection rates |

Adolescents and adults (12-79) with asthma; special subgrouP > 60 y with mild-to-moderate and severe asthma (including use of OCS) | No healthy controls for comparison |

| Pedrosa et al., (2009)122 | Mexico | 2001-2002 influenza season | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study | Inactivated TIV (H1N1, H3N2, B); dose 15 μg per strain; twice at 28 d interval | Safety: local and systemic adverse events; lung function; short-term rate of seroconversion; HI assay | Significant rate of seroconversion after the first and second dose for all 3 strains. | Children 5-9 y with mild intermittent and moderate asthma |

No healthy controls for comparison. Study funded by industry. Asthma severity assessed only as LF; no data on exacerbations. Subjects with a history of allergy to egg protein excluded. Previous influenza vaccination status not reported |

| Zuccotti et al., (2007)123 | Italy | 2005-2006 influenza season | Observational, prospective, open-label multicenter study | Virosomal-adjuvanted TIV (H1N1, H3N2, B); dose 15 μg per strain; single dose |

Short (at 1 mo)- and long-term (at 6 mo) seroconversion (≥1:40) and seroprotection (≥1:10); HI assay; both rate and fold increase in GMT. Seroconversion and seroprotection in relation to preexisting antibodies. Safety: local and systemic adverse events |

Seroconversion: Both rates and GMT significantly high at both 1 and 6 mo for all 3 strains Better GMT increase for the B strain in children 6-9 y compared to 3-5 y. Seroprotection: At 1 m satisfactory in both age groups, decreased seroprotection for H3N2 for children aged 6-9 y. At 6 mo: >80% in children aged 6-9 y; significantly lower (<70%) in children aged 3-5 y. Both seroconversion and seroprotection to any specific strain significantly lower without preexisting antibodies |

Children with asthma aged 3-9 y (subgroups 3-5 y and 6-9 y) | No data on asthma severity. No healthy controls. More than 50% of children had preexisting antibodies at baseline. Baseline GMTs were relatively high for all 3 strains. Subjects with history of egg allergy and/or severe atopy were excluded |

| Section 5 Efficacy of influenza vaccines in asthma | ||||||||

| Abadoglu et al., (2004)125 | Turkey |

Recruitment: September-November 2001. Follow-up until March 2002 |

Randomized, controlled trial | TIV vs. no vaccine | Frequency of URTIs and asthma exacerbations during the winter following vaccination. | URTI and asthma exacerbation rates similar between vaccinated and nonvaccinated groups = no protective effect | Adults with asthma aged 22-84 y. In total: 128 Vaccination: 86 Nothing: 42 |

Lack of knowledge on rate of influenza epidemic in tested period or on the cause of URTI. Relatively low number of subjects enrolled |

| Bueving et al., (2004)126 | The Netherlands |

1999-2000 2000-2001 |

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study | TIV vs. placebo | Symptom scores (to detect infection); pharyngeal swab and spirometry; quality of life (QoL) | In influenza-positive weeks of illness: no effect was found for respiratory symptoms recorded in the diaries—moderately beneficial effect on QoL throughout the seasons: No differences for respiratory symptoms and QoL |

Children with asthma aged 6-18 y. In total: 696 (296 in 1999-2000 and 400 in 2000-2001) 347: influenza vaccine and 349 placebo |

Relatively few influenza-positive weeks of illness |

| Bueving et al., (2004)81 | The Netherlands |

1999-2000 2000-2001 |

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study | TIV vs. placebo |

Symptom scores (to detect infection) Pharyngeal swab. Blood samples for influenza virus-specific antibodies (immunogenicity) |

Influenza vaccination did not result in a significant reduction in the number, severity, or duration of asthma exacerbations caused by influenza | 696 children with asthma aged 618 y | |

| Fayyaz Jahani et al., (2012)127 | Iran | ND | Randomized, placebo-controlled study | TIV | Asthma exacerbations | Lower asthma exacerbation rates following TIV (13%) than after placebo (53%) | 140 children with asthma aged 6-60 mo | Conference abstract, thus limited information |

| Fleming et al., (2006)128 | Multicenter (UK & Europe) | October 2002-May 2003 | Reactive CT to examine relative efficacy of CAIV-T vs. TIV | CAIV-T vs. TIV | Surveillance for influenza-like symptoms. Nasal swab viral culture culture-confirmed influenza illness. Primary efficacy endpoint: incidence of culture-confirmed influenza illness caused by a community-acquired subtype antigenically similar to that in the vaccine |

CAIV-T had a significantly greater relative efficacy of 35% compared with TIV. There was no evidence of a significant increase in adverse pulmonary outcomes for CAIV-T compared with TIV. CAIV-T was well tolerated in children and adolescents with asthma |

Children with asthma aged 6-17 y. CAIV-T (n = 1114) and TIV (n = 1115) |

No placebo group; therefore, the absolute efficacy of each vaccine cannot be calculated |

| Ambrose et al., (2012)131 | Meta-analysis of 2 randomized, multinational trials | CAIV-T vs. TIV | Culture-confirmed influenza illness during the influenza surveillance period. Rate of wheezing, hospitalization, adverse events | Children receiving LAIV had fewer cases of culture-confirmed influenza illness than TIV recipients | 1940 children aged 2-5 y with asthma or prior wheezing |

Post hoc definition of study cohorts, but this is in part addressed by the subpopulation analysis. Identification of subjects with asthma or history of wheezing relied on investigator judgment without validation |

||

| Section 6. Effectiveness of influenza vaccination in asthma | ||||||||

| Christy et al., (2004)137 | USA | 1996-1997 | Retrospective nested case-control study | Influenza vaccine | Asthma-related hospitalization, clinic and emergency department visits |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) associated with vaccine for asthma related: Hospitalization 1.9 (0.9-3.9). Clinic visit 2.9 (2.0-4.1). Emergency department visits 2.0 (1.2-3.1) |

Primary care cohort. 400 randomly selected children with asthma who had been vaccinated, and 400 who had not. Age range 1-19 y |

Two groups were not balanced in terms of ethnicity and likelihood of receiving vaccine in previous year, but this was taken into account in adjusted analysis. Study suggests that vaccine associated with worse outcomes. Patients with more severe asthma or those more likely to present may be more likely to have been vaccinated although controlling for these did not alter the results |

| Hak (2005)136 | Netherlands | 1999-2000 | Nested case-control study | Influenza vaccination | All cause mortality, hospitalization, general practice visits for influenza, pneumonia, and other acute respiratory problems |

High-risk children <18 y, 43% (10%-64%) of visits were prevented by vaccination after adjustment. High-risk adults (18-64 y) 78% of deaths (39%-92%), 87% of hospitalizations (39%-97%), and 26% of GP visits (7%-47%) were prevented. Elderly persons vaccine prevented 50% of deaths (95% CI, 23%-68%) and 48% of hospitalization (7%-71%) were prevented |

All age groups with long-term medical conditions. >75 000 patients in primary care cohort | No separate analysis for asthma. Adjusted for previous medical utilization and comorbidities |

| Herrera et al., (2007)138 | USA | 2003-2004 | Case-control study | Influenza vaccine | Laboratory-confirmed influenza report |

Influenza: Vaccine “efficacy” was 60% (43%-72%) and 48% (21%-66%) among those without and with high-risk medical conditions. Influenza-related hospitalization: Vaccine “efficacy” was 90% (68%-97%) and 36% (0%-63%) against for persons without and with high-risk conditions |

330 cases, 1055 randomly recruited controls. Age range 50-64 y |

No separate data for asthma. Apparent effectiveness may be inflated by potential tendency to not test vaccinated people and miss an influenza diagnosis on a vaccinated patient. Authors say “efficacy” but study set up as an effectiveness study. Vaccine strains did not closely match circulating influenza strains |

| Koshio et al., (2014)132 | Japan | September-October 2010 | Survey | Vaccination against “new type of influenza”: H1N1 pdm09 | Report of a “new type of influenza”: H1N1 pdm09 |

For influenza, OR (95% CI) for previous vaccination was 0.62 (0.42-0.90) for younger patients ≤61 y); among older patients OR was 1.38 (0.66-2.89) For infection-induced asthma exacerbation, OR (95% CI) for previous vaccination was 1.67 (0.60-4.66) for younger patients and 1.71 (0.50-5.83) for older ones |

2555 adults with asthma | There may have been other differences between vaccinated and nonvaccinated patients that explained the difference in risk of influenza. Influenza cases were not laboratory proven. This study looked at pandemic rather than ordinary influenza |

| Kramarz et al., (2001)133 | USA | 1993-1996 | Population-based, retrospective cohort study | Influenza vaccine | Exacerbation of asthma | Adjusted incidence rate ratios of asthma exacerbations after vaccination were 0.78 (0.55-1.10), 0.59 (0.43-0.81), and 0.65 (0.52-0.80) compared with the period before vaccination during the 3 influenza seasons | Children aged 1-6 y with asthma in 4 large health maintenance organizations. (>70 000 patients) |

As a database-based analysis, the asthma diagnostic labeling and recording of asthma exacerbations may not be completely accurate. Differences in patients receiving vaccination may have explained the difference in exacerbations. Adjusted for asthma severity |

| Ong et al., (2009)135 | USA | Survey | Influenza vaccine | Exacerbation of asthma defined by oral corticosteroid, hospital visit or emergency department visit | In the multivariate analyses, current influenza vaccination status was independently associated with significantly decreased OR of using oral steroids in the previous 12 mo (0.29, 0.10-0.84). There was no association with hospitalization (1.39; 0.340-5.67) nor emergency department visits | 80 children with asthma in a pediatric clinic |

Retrospective approach may have introduced recall bias. Factors influencing likelihood of vaccination may have influenced likelihood of exacerbation, confounding the results. Triggers other than influenza may have been responsible for the exacerbation |

|

| Smits et al., (2002)134 | Netherlands | 1995-1997 | Retrospective cohort study | Inactive influenza vaccination | Physician-diagnosed acute respiratory illness. |

Vaccine effectiveness was 27% (−7% to 51%) after adjustments. For those <6 y, it was 55% (20%-75%) compared with −5% (−81%-39%) in older ones |

Children with asthma aged 0-12 y in primary care. Over 300 patients in each season | Patients vaccinated may have been different to others, and these factors may have impacted on likelihood of developing respiratory illness. Adjusted for previous healthy utilization |

| Jaiwong et al., (2015)196 | Thailand | June 2012-August 2013 | Cross-sectional nonrandomized study | TIV vs. no vaccine | Respiratory illnesses and asthma-related events | The immunized group had significantly reduced: acute respiratory tract illnesses; asthma exacerbations; ER visits; bronchodilator usage and systemic steroid administrations; number of hospitalizations (P < .001) and their duration (P < .034) | 93 children with mild persistent asthma aged 1-14 y (48 patients: 2 doses of inactivated influenza) | Nonrandomized study. Small sample size. Lack of info related to other confounding factors in asthmatic exacerbations such as compliance and controller usage, other virus and bacterial infections, pollution, emotional conditions of the patient |

| Yokoushi et al., (2014)197 | Japan | May 2009-February 2010 | Retrospective, cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey | Inactivated, split-virus, nonadjuvanted monovalent vs. no vaccine | Vaccination rates. Vaccine effectiveness against physician-diagnosed influenza A infection, and consecutive asthma exacerbations |

Comparison of positive influenza diagnosis rates between vaccinated and unvaccinated children with and without asthma showed that: Unvaccinated children with asthma had an elevated odds ratio (13.235; 95% CI; 5.564-32.134). Treatment for asthma exacerbations was needed in a larger proportion of unvaccinated children. Vaccine effectiveness against physician-diagnosed influenza was 87% (95% CI, 78%-93%) overall, 92% (95% CI, 81%-96%) in children with asthma, and 81% (95% CI, 63-91%) in children without asthma, respectively |

460 children with (n = 144) and without asthma (n = 316) | Other environmental factors that may cause asthma exacerbation were not considered. No data on atopic comorbidities. Retrospective study. Physician-diagnosed influenza infection with or without a positive rapid antigen test result for influenza A during the pandemic period |

| Section 7. Safety of influenza vaccines in asthma | ||||||||

| Greenhawt et al., (2012)146 | USA | October 2010-March 2012 | Phase 1: randomized, controlled trial. Phase 2: retrospective, observational trial |

Phase 1: Group A: graded 2 dose TIV challenge Group B: sham (saline) 1st dose followed by full TIV dose Phase 2: participants who declined study and received TIV from their allergist or had already received TIV in primary care |

Safety of TIV in egg-allergic children with severe allergy | No allergic reactions were recorded | Egg-allergic children with severe allergy (mean age 12 y). All patients had previous confirmed severe allergic reactions to egg | |

| Howe et al., (2011)147 | USA |

Phase 1: October 2004-February 2009 Phase 2: 2009-2010 |

Phase 1: Retrospective, observational study. Phase 2: Prospective observational study | TIV | Safety of TIV in egg-allergic and nonallergic patients | No severe allergic reactions have been recorded | Children | |

| Miller et al., (2003)143 | USA | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. | Influenza vaccine | T-cell immune response to vaccine components in patients with asthma who experience bronchospasm |

Increased influenza (but not egg) antigen-induced mononuclear cell proliferation, unrelated to asthma exacerbations after vaccine. No differences in cytokine production in response to either influenza or egg antigen in association with asthma exacerbations. Bronchospasm after immunization is not related to vaccination |

Adults, mean age 43 y | ||

| Chung et al., (2010)144 | USA | 2002-2009 | Retrospective, observational study | Influenza vaccine | Tolerability of the vaccine, defined as the lack of localized or systemic adverse reactions, in egg-allergic and nonallergic patients | 95% of egg-allergic patients who received the vaccine skin test tolerated the influenza vaccine without any serious adverse reactions | Children, 6 mo-18 y | |

| Gagnon et al., (2010)145 | Canada | October-December 2009 | Prospective, observational study | Adjuvanted monovalent 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 influenza vaccine | Risk of anaphylaxis in children with egg allergy administered an adjuvanted monovalent 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 influenza vaccine. | No patient had an anaphylactic reaction | Children and adults. | |

| Greenhawt et al., (2010)149 | USA | October 2009-February 2010 | Controlled, prospective trial | H1N1 influenza vaccine | Safety of administering H1N1 to egg-allergic patients compared with non-egg-allergic, pediatric, control patients. | No significant allergic reactions were recorded | Children and adults aged 6 mo to 24 y | |

| Esposito et al., (2008)148 | Italy | November-December 2007 | Prospective study | Virosomal-adjuvanted influenza vaccine | To evaluate whether the virosomal-adjuvanted influenza vaccine that has been shown to have the lowest egg protein content could be administered to children with even severe egg allergy without any risk of allergic reactions | Administration of the whole vaccine was safe and well tolerated by all of the children, with no differences between those with and without egg allergy, or between those with egg allergy of different severity | Children >3 y | |

| Castro et al., (2001)140 | USA | September-November 2000 | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial | TIV or placebo | Safety of TIV in adults and children with asthma | The frequency of asthma exacerbations was similar in the 2 wks after the TIV or placebo injection. The exacerbation rates were similar in subgroups defined according to age, severity of asthma, and other factors | Children and adults aged 3-64 y | |

| Baxter et al., (2012)141 | USA | October 2003-March 2008 | Prospective observational postmarketing study | LAIV, TIV or placebo | Safety of LAIV, compared to TIV and placebo in children | Asthma/wheezing major adverse events were not statistically increased in LAIV recipients. No anaphylaxis events occurred | Children aged 5-17 y | |

| Ambrose et al., (2012)131 |

Study 1: 2004-2005 Study 2: 2002-2003 |

Post hoc analysis of 2 randomized, multinational trials of LAIV and TIV in children aged 6-71 mo | LAIV vs. TIV | Safety of LAIV in children with asthma younger than 6 y | Wheezing, lower respiratory illness, and hospitalization were not significantly increased in children receiving LAIV compared with TIV. Increased upper respiratory symptoms and irritability were observed in LAIV recipients | Children aged 2-5 y | ||

| Gaglani et al., (2008)142 | USA | 1998-2002 | Open-label field trial | Trivalent LAIV | Safety of the intranasal LAIV3 in children with intermitted wheezing/asthma | No increased risk for medically attended acute respiratory illnesses, including asthma exacerbation | Children aged 1.5-18 y | |

| Haber et al., (2015)198 | USA |

LAIV4 reports: 2013-2014 LAIV3 reports: 2010-2013 |

Analysis of reports received at the “Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System” | LAIV4 vs. LAIV3 | Medical records were reviewed for nonmanufacturer serious reports (ie, death, hospitalization, prolonged hospitalization, life-threatening illness, permanent disability), and reports of selected conditions of interest. | No new or unexpected safety concerns with LAIV4. The safety profile of LAIV4 was similar to LAIV3. Just over 94% of LAIV4 reports were nonserious, and the most common adverse events were mild, self-limited conditions (eg, fever, headache, and cough) | Children and adults aged 2-49 y. 12.7 million doses of LAIV4 were distributed. | General limitations of passive surveillance. |

| Turner et al., (2015)151 | UK | September 2013-January 2014 | Prospective, multicenter, open-label, phase IV intervention study | LAIV | Clinical symptoms after LAIV administration to estimate incidence of 1. Allergic reaction within 2 h, 2. Delayed allergic symptoms within 72 h, 3. Nonallergic adverse events; and change in nasal airway patency (acoustic rhinometry). |

LAIV appeared to be safe in children with egg allergy and additional asthma or recurrent wheeze. No systemic allergic reactions reported. Eight children had mild, self-limiting, potentially IgE-mediated allergic symptoms. 26 (9.4%; 95% CI for population, 6.2%-13.4%) children experienced lower respiratory tract symptoms within 72 h, including 13 with parent-reported wheeze. None of these episodes required medical intervention beyond routine treatment |

282 children with egg allergy aged 2-17 y | The egg protein content of LAIV batches may vary; thus, data from this study may not be applicable to future LAIV stocks in which egg content may be higher |

| Section 8 Antiviral treatment against influenza in patients with asthma | ||||||||

| Johnston et al., (2005)168 | Randomized study | Oseltamivir (2 mg/kg) or placebo twice daily, as a syrup | Effects of oseltamivir among influenza-infected children with asthma | Oseltamivir is safe and well tolerated among children with asthma, may reduce symptom duration and helps improve lung function and reduce asthma exacerbations during influenza infection | Children with asthma aged 6-12 y. Analysis was performed for both the intent-to-treat infected (n = 179) and per-protocol (n = 162) populations | |||

| Lin et al., (2006)162 | China | 2002-2003 | Randomized, open-label, controlled trial | Oseltamivir 7 5 mg twice daily for 5 d (oseltamivir group), or symptomatic treatment (control group) within 48 h after symptom onset | Duration and severity of illness in influenza-infected patients, incidence of complications, antibiotic use, hospitalization, and total medical cost | Oseltamivir is effective and well tolerated in high-risk patients with chronic respiratory or cardiac diseases. It can reduce the duration and severity of influenza symptoms and decrease the incidence of secondary complications and antibiotic use, without increasing the total medical cost | 118 Chinese patients (mean age 48.1 y) with chronic respiratory diseases (chronic bronchitis, obstructive emphysema, bronchial asthma or bronchiectasis) or chronic cardiac disease. | Only 8 patients with bronchial asthma |

| Cass et al., (2000)166 | UK | 2000 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, 2-way crossover study, 7-d washout period | 10 mg zanamivir as a dry powder (265 mg) or a placebo, twice daily on day 1 and then 4 times daily from day 2 to day 14 | Safety of zanamivir in patients with asthma | Zanamivir inhaled as a dry powder does not significantly affect the pulmonary function and airway responsiveness of subjects with mild/moderate asthma, and therefore, its use in such patients/subjects is not precluded | 13 subjects, aged 19-49 y, with asthma | |

| Shun-Shin et al., (2009)169 | Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials | NA | Effects of the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir and zanamivir in treatment of children with seasonal influenza and prevention of transmission to children in households | Oseltamivir did not reduce asthma exacerbations or improve peak flow in children with asthma | Children aged ≤ 12 y in the community (not admitted to hospital) with confirmed or clinically suspected influenza | Based on only 1 trial | ||

| Jefferson et al., (2014)170 | Systematic review | NA | Potential benefit and harm of oseltamivir by reviewing all clinical study reports (or similar document when no clinical study report exists) of randomized placebo-controlled trials and regulatory comments | Oseltamivir had no effect in children with asthma, but there was an effect in otherwise healthy children | Children and adults who either were healthy before exposure to respiratory agents or had a chronic illness (such as asthma, diabetes, hypertension) but excluding people with immune suppression | |||

| Jefferson et al., (2014)171 | Cochrane review | NA | Potential benefit and harm of neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza in all age groups by reviewing all clinical study reports of published and unpublished randomized, placebo-controlled trials and regulatory comments | For the treatment of adults, oseltamivir reduced the time to first alleviation of symptoms by 16.8 h (95% CI 8.4-25.1, P < .0001). This represents a reduction in the time to first alleviation of symptoms from 7-6.3 d. There was no effect in children with asthma, but in otherwise healthy children there was a reduction by 29 h (95% CI 12-47 h, P = .001) | All age groups. 53 trials in Stage 1 and 46 in Stage 2 (formal analysis), including 20 oseltamivir (9623 participants) and 26 zanamivir trials (14 628 participants) | |||

| Watanabe, (2013)173 | Japan | 2009 | Double-blind, randomized controlled trial |

Laninamivir group: singe inhalation of 40 mg laninamivir and placebo oseltamivir capsules twice daily for 5 d. Oseltamivir group: 1 capsule (75 mg) of oseltamivir orally twice daily for 5 d and laninamivir placebo powder once on day 1 |

Efficacy and safety of laninamivir octanoate, an inhaled neuraminidase inhibitor for the treatment of influenza patients with chronic respiratory diseases | Laninamivir octanoate showed similar efficacy and safety to oseltamivir in the treatment of influenza, including that caused by influenza A(H1N1) 2009, in patients with chronic respiratory diseases | 203 patients aged ≥20 y. Most patients had underlying bronchial asthma | |

| Kohno (2011)172 | Japan | January-May 2009 | Multicenter, uncontrolled, randomized, double-blind study | Peramivir intravenously administered at 300 or 600 mg/d for 1-5 d, as needed | Efficacy and safety of the novel anti-influenza virus drug peramivir in high-risk patients | In the 600 mg group about 50% shorter duration of illness. In 33% of patients adverse drug reactions, described as “not particularly problematic clinically” with quick recovery in all cases | 37 influenza patients, ≥20 y, with risk factors, including asthma | 5 patients with asthma were also taking steroids |

| Biggerstaff et al., (2014)199 | USA | 2009-2010 | US state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey | None | Influenza antiviral treatment prescription in influenza-like illness (ILI) | 26% of respondents with ILI received clinical influenza diagnosis. Of these 36% received antiviral treatment. Being younger and employed but not high-risk conditions, including asthma, were associated with antiviral treatment | 216 431 adults ≥18 y, noninstitutionalized |

Data in this study are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability bias. Diagnosis and treatment are not verified |

| Biggerstaff et al., (2014)165 | USA | 2010-2011 | US state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey | None | Influenza antiviral treatment prescription in influenza-like illness (ILI) | Among adults with a physician diagnosis of influenza, 34% received antiviral treatment. Having asthma was not associated with antiviral treatment | 75 088 adults (18->65 y) and 15 649 children (0-17 y) were interviewed |

Data in this study are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability bias. Diagnosis and treatment arte not verified |

- ACT, asthma control test; BMI, body mass index; CAIV-T, trivalent, cold-adapted influenza vaccine; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER, emergency room; GMT, geometric mean titer; GP, general practitioner; HI, hemagglutinin inhibition; HIC, high-income companies; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; ICU, intensive care unit; LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; LF, lung function; LMIC, low-middle-income countries; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; NA, not available; NAI, neuraminidase inhibitor; NS, not significant; OCS, oral corticosteroids; OR, odds ratio; QoL, quality of life; RR, risk ratio; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARI, severe acute respiratory infection; SPT, skin prick test; TIV, trivalent influenza vaccine; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

- a As reported in the original article.

3 GLOBAL BURDEN OF INFLUENZA IN PATIENTS WITH ASTHMA

3.1 Influenza-attributable healthcare utilization in asthma patients

Asthma is the most common underlying disease in patients with influenza admitted to healthcare facilities, both in adults19-33 (7.6%-46%34, 35) and in children26, 36-47 (8.3%-42%48, 49). Children with asthma accounted for a significantly larger proportion of those hospitalized with pandemic H1N1 than with seasonal influenza.24, 50-53 Asthma was also the most common comorbidity among pregnant women hospitalized with H1N1 infection, with a prevalence ranging from 8% to 33%.54-57

Asthma represented a risk factor for hospitalization during influenza seasons in the general population,58 with an OR of 2.6 (95% CI 1.6-4.0) in 2 Canadian studies,59, 60 and a relative risk (RR) of 4.47 (95% CI 1.49-13.39) in Israel.61 The same applied to children,47, 62, 63 where asthma conferred a 4-fold risk of hospitalization (the United States,64 Germany,41 and Argentina65), with a 21-fold risk observed in South Korea.66 Interestingly, influenza-related hospitalization costs in children with asthma may be lower than in children with other chronic conditions and were very close to costs in children without comorbidity.67

Asthma patients seemed to have a higher risk of being admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or to have a more severe disease course when hospitalized for influenza,26, 33, 43, 45, 50, 66, 68-70 with an OR of 4.92 (95% CI 1.38-17.33) in Argentinean children 69 and a RR of 15.20 (95% CI 1.16-199.63) in China >15 years of age.71 Severe disease was especially common in those developing pneumonia,33 but did not seem to be related to the severity of underlying asthma.51 In a multivariate analysis of H1N1 pediatric patients, asthma was associated with increased mortality in ICU-admitted children and adolescents (OR 1.34, P = .05).68 However, a retrospective analysis performed in the UK on 1,520 patients showed that patients with asthma hospitalized because of influenza A infection were less likely to require ICU or die compared with those without asthma, with an OR of 0.51 (95% CI 0.36-0.72) for severe outcome.28 Two other studies confirmed this finding,25, 29 which may be even more pronounced in those with preadmission inhaled (OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.18-0.66) or systemic corticosteroid treatment (OR 0.36 95% CI 0.18-0.72) for asthma and an earlier hospital admission (within 4 days from symptom onset—adjusted OR 0.60 95% CI 0.38-0.94).28

3.2 Influenza-induced acute asthma exacerbations

Influenza, like other respiratory viral infections, can lead to AAE and was found to account for 32.0%72 and 9.8%73 of AAEs in 2 studies of adult outpatients with asthma. However, the method used to identify the presence of influenza in AAE episodes largely determines the outcome. A direct comparison of molecular (PCR), serological, and immunofluorescent (IFA) detection in the same cohort of adults with asthma found influenza rates of 24.0%, 18.3%, and 2.0%, respectively, in AAEs.74 Thus, the validity of studies that applied conventional influenza identification techniques such as cytopathic effect in cell culture followed by indirect immunofluorescence to confirm viral presence75 is questionable. Among hospitalized adults with asthma patients, rates of influenza-induced AAE were reported at 10.0%,76 19.0%,77 20.7%,78 and as high as 37.9%.73

Available data on influenza-associated AAE among children vary considerably. For outpatient visits, 3 studies did not detect any influenza-positive samples,75, 79, 80 while several groups identified influenza infection as the cause of AAE, with most reporting rates of influenza-positive samples between 2.4% and 15.5%.63, 81-84 A recent study showed an accentuated propensity for loss of asthma control when children were infected with pH1N1 (38%) compared with other common respiratory virus infections.85 Among children with asthma hospitalized for severe AAE, 3 studies reported an influenza-associated burden of 2.6%,82 3.4%,86 and 3.7%63 of AAEs. In summary, there were significant inter- and intragroup variations in the reported influenza-induced AAE burden among children and adults with asthma, with fewer studies on adults.

Various factors compromise the interpretation of the available data. First, the use of different diagnostic methods for influenza detection may significantly influence the study outcome. The advent of molecular techniques and their universal use may solve this issue. Second, the absence of harmonized criteria for appropriate inclusion of patients and the lack of a standardized definition and diagnosis of influenza infection disallow direct comparison of results and complicate the identification of relevant studies. Third, the lack of large cohorts of patients with asthma studied for influenza-induced AAE raises questions about the validity of the currently available findings. Furthermore, seasonal rather than perennial influenza testing and selective testing only in hospitalized AAE cases could lead to inaccurate estimation of the actual contribution of influenza to AAEs.

4 CURRENT INFLUENZA VACCINE RECOMMENDATIONS AND COVERAGE FOR PEOPLE WITH ASTHMA

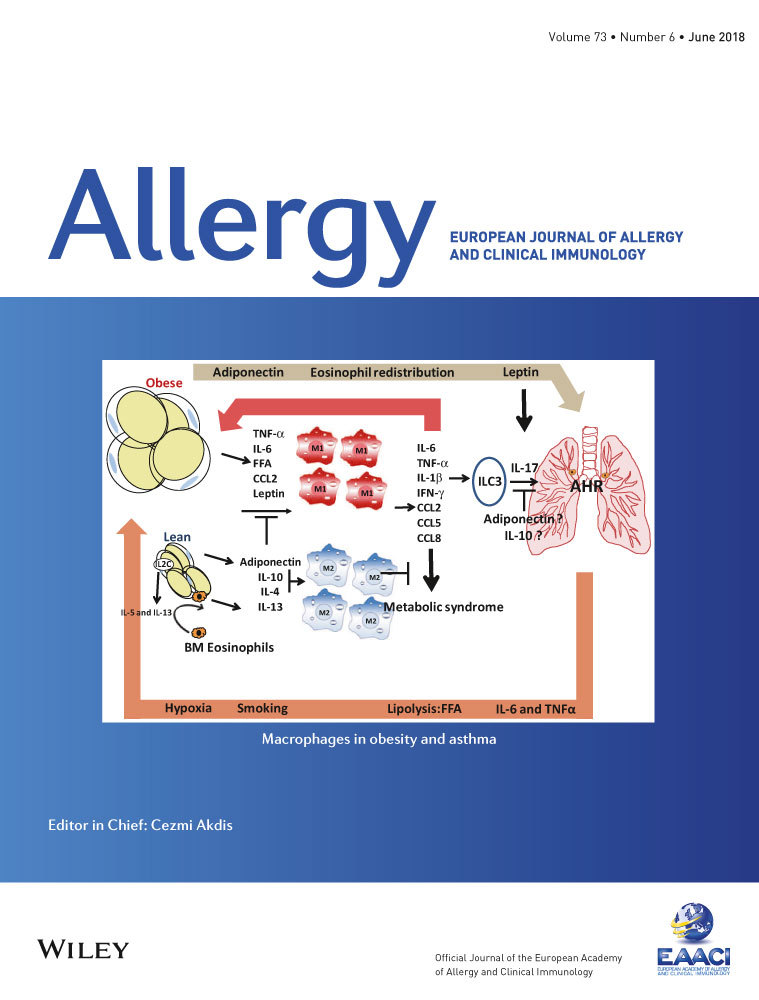

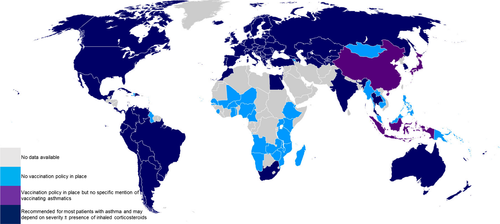

In common with most economically developed nations (Figure 1), all 28 countries of the European Union currently recommend influenza vaccination of people with chronic respiratory disease, including asthma.87-89 Trivalent (TIV) and quadrivalent inactivated split-virus influenza vaccines are available, with TIV being the most widely used throughout the EU. An intradermal vaccine is also available, and more recently, a quadrivalent live attenuated intranasal vaccine (LAIV) was approved for use in the UK in children aged 2-18 years.88, 90

However, vaccine uptake for clinical risk groups varied from 31% in Portugal to 82% in Northern Ireland,88, 91 as did influenza vaccination coverage of adults with asthma, with 30%-50% in Spain92-95 and 40% in the UK.96 Self-reported uptake of seasonal influenza vaccine among adults with asthma in the United States varied from 54% in the community to 71% in secondary care.97 Children with asthma had significantly lower coverage rates of approximately 18%-20% in Spain,93, 98 15% in France,99 and 2.5%-20% in Italy, across multiple seasons.91 In comparison, in the United States vaccination coverage reached around 50% in adults and children.100

To address the question of such historically low vaccination rates among those with asthma, many studies employed cross-sectional surveys to analyze the socio-demographic variables that predict vaccine uptake. The strongest factors associated with higher vaccine coverage were older age, recent contact with healthcare providers, nonsmoking status, presence of comorbidities, more severe asthma, and (surprisingly) lower household income,92-95, 100-106 although there are conflicting reports for the latter.98 Variables that were associated with lower vaccination uptake included younger age groups,96, 100, 107, 108 belonging to certain ethnic groups,102, 105, 108 and lack of awareness about the vaccine.91, 99, 100 A more detailed exploration assessing health attitudes suggested that the misbelief that the vaccination was not necessary or could actually cause influenza or side effects was predictive of nonadherence97, 109-112 and contributed to lower vaccination coverage.96, 107, 108 Reports of low effectiveness probably also contributed to poor uptake.18, 113, 114

Healthcare worker endorsement of vaccination was highly predictive of adherence.109, 110, 112 A survey of 1225 US allergists suggested that 85% of these offered influenza vaccinations to adults and children. Younger allergists (<45 years) were more likely to offer vaccination, especially to children.115 Pediatricians were more likely than family physicians to routinely recommend influenza vaccination to children with asthma (adjusted OR 3.49, 95% CI 1.68-7.22), with decisions also being made depending on asthma phenotype (ie, intermittent vs. persistent).116

The success of vaccination programs was affected by complex factors such as the nature of healthcare provision (eg, free care or insurance-based), education levels, and cultural acceptance of the vaccine. Therefore, national health surveys with information on vaccination status linked with medical and socio-demographic details (such as that of Spain with data spanning more than 2 decades92-95, 117) can aid in assessing the impact of influenza vaccination, at population level.

Simple interventions such as allowing for year-round scheduling of appointments for vaccination can be effective.118 Nevertheless, it is likely that only major policy shifts will lead to significantly higher vaccination rates, due to more clear and consistent messaging about the importance and acceptability of influenza vaccination to patients and healthcare workers alike. This is illustrated by the increase in influenza vaccination uptake among children with asthma from 36% (2005-2006) to 50% (2010-2011) after the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advised vaccinating all children, regardless of risk.100 With its favorable safety and cost-benefit profile,18, 119, 120 there is a need for health campaigns to raise awareness among the public and clinicians of the benefits of influenza vaccination and to improve implementation of guidelines.

5 IMMUNOGENICITY OF INFLUENZA VACCINES IN ASTHMA

There is uncertainty about the level of protection that influenza vaccines afford in people with asthma. Influenza vaccine immunogenicity, a prerequisite for protection, is usually assessed by hemagglutinin inhibition assay (HI) measuring seroprotection rate (percentage of subjects with antibody titers ≥1:40), seroconversion rate (percentage of subjects with ≥4-fold increase in antibody titer), antibody geometric mean titer (GMT), and GMT ratio (GMT postvaccination/GMT prevaccination).

We identified limited data on influenza vaccine immunogenicity in asthma. Only 1 study of TIV in children aged 0.5-3 years compared healthy controls to recurrent wheezers. It found good and similar seroconversion and seroprotection rates to all 3 vaccine strains (H1N1, H3N2, and B) in both groups (after 1 month), with higher pre- and postvaccination GMTs in children with wheeze, but a higher GMT ratio in healthy controls.121 In children with asthma, TIV and a virosomal-inactivated subunit influenza vaccine induced good seroprotection and seroconversion at 1 month in both preschool and school-age children, with some reduction in GMTs by 6 months.122, 123 A 2009 H1N1 vaccine given to adolescents and adults induced equally good seroprotection if 15 or 30 μg vaccine was given in those with mild-to-moderate asthma. In contrast, in severe asthma the higher dose resulted in better seroprotection, which in elderly severe asthma patients (≥60 years) was only achieved with the high 30 μg dose.124 In the latter group and in young children with recurrent wheeze, corticosteroid treatment or corticosteroid dose did not influence influenza vaccine immunogenicity.121, 124

6 EFFICACY OF INFLUENZA VACCINES IN ASTHMA

Data on the efficacy of influenza vaccination in asthma are limited, with only 2 randomized studies addressing the efficacy of TIV in patients with stable asthma. One study, conducted in Turkey, included 128 adults with asthma who received either TIV or no vaccination.125 No significant difference in the frequency of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) or AAE rate was found between vaccinated and nonvaccinated participants; however, this study had significant limitations (see Table 1). In a larger randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial from the Netherlands81 in 6- to 18-year-old children with asthma, TIV had no significant effect on the number, severity, or duration of AAEs caused by confirmed influenza infection, or on the respiratory symptoms recorded; however, it moderately improved quality of life during the weeks of influenza-positive illness.126 In contrast, a conference abstract127 reported significantly lower AAE rates in children <5 years with asthma following TIV (13%) compared with placebo (53%).

For LAIV, we found no efficacy data in asthma compared to nonvaccination. A large European multicenter, randomized, open-label trial compared intranasal cold-adapted LAIV to intramuscular TIV in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years with asthma and reported a 34.7% reduction in culture-confirmed influenza illness after LAIV.128 A reanalysis of efficacy data from 2 randomized, multinational trials129, 130 comparing LAIV to TIV demonstrated that 2- to 5-year-old children with mild-to-moderate asthma or prior wheezing receiving LAIV had fewer cases of culture-confirmed influenza illness than TIV recipients.131

7 EFFECTIVENESS OF INFLUENZA VACCINATION IN ASTHMA

While efficacy studies reflect a treatment's performance in tightly controlled clinical trials, effectiveness studies reflect how well a treatment works in practice and are more representative of real life. Influenza vaccination may be less effective than expected due to differences between the characteristics of patients vaccinated in the general population and those recruited into efficacy trials. Furthermore, the influenza vaccine may not contain the prevalent virus strain, and vaccine coverage may be suboptimal.

There are limited data on the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in patients with asthma or high-risk populations that included asthma. Six studies assessed the effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines, while 1 other studied the H1N1 pandemic vaccine.132

In children, 2 retrospective cohort studies found that influenza vaccination was associated with a reduction in the rate of asthma exacerbations133 and fewer acute respiratory problems (only in those <6 years of age).134 A survey found that vaccination in children with asthma was associated with less use of rescue prednisolone,135 while a nested case-control study suggested that influenza vaccination was associated with fewer acute general practice visits for respiratory problems in children with long-term conditions.136 However, another case-control study suggested that vaccination was associated with an increased risk of unscheduled attendance for asthma care.137 In this study, the cases and controls were poorly balanced in terms of ethnicity and likelihood of vaccination in previous years. Although an adjusted analysis was undertaken, this may not have taken into account all the differences between the groups.

Only 1 study focused on adults with asthma.132 In this study, the H1N1 influenza vaccine was found to be protective against influenza in those aged under 61 years, but not in older patients. Also, it did not protect against AAE. Two other studies enrolled adults with long-term136 or high-risk conditions138; the first demonstrated a reduction in general practice visits, hospitalization and deaths from respiratory problems, while the second demonstrated a protective effect against influenza and influenza-related hospitalization. Asthma was not analyzed separately in these studies, and it is thus not clear whether influenza vaccination was beneficial to people with asthma.

A recent systematic review reports a 59%-78% reduction in asthma attacks leading to emergency visits and/or hospitalizations after influenza vaccination and a vaccine effectiveness of 45% (95% CI 31-56) for laboratory-confirmed influenza in people with asthma based on a meta-analysis of 2 test-negative design case-control studies.139

8 SAFETY OF INFLUENZA VACCINES IN ASTHMA

Large retrospective and prospective studies have demonstrated the safety of influenza vaccines in children and adults with asthma, for both TIV and LAIV.131, 140-142 In these studies, vaccinated patients did not have more frequent asthma exacerbations than unvaccinated patients, and no other adverse event was more common in patients with asthma. A study of adult asthma patients who reported bronchospasm after influenza vaccination indicated that these symptoms were not related to vaccine hypersensitivity.143

A common concern is the safety of egg-derived influenza vaccines in patients with egg allergy, a frequent comorbidity in children with asthma. The last case of anaphylaxis after influenza vaccination occurred more than 25 years ago at a time when the egg content of vaccines was much higher. The ovalbumin content of most current vaccines is <1.2 μg/mL, and an egg-free influenza vaccine is also available. Several studies demonstrated that influenza vaccines containing low levels of egg protein (≤1.2 μg/mL) were safe even in egg-allergic patients.143-149 This also seemed to be true in egg-allergic patients with associated asthma. The recent SNIFFLE studies of LAIV in egg-allergic children, including 634 children with asthma/recurrent wheeze (79.7% on daily inhaled corticosteroid treatment), found no immediate systemic allergic reactions.150, 151 For 6.6% of children with asthma/recurrent wheeze, the parents reported wheeze within 72 hours of LAIV, but most wheeze episodes only required routine treatment; there was no hospitalization and no increase in respiratory symptoms in the 4 weeks after LAIV.

Based on the robust evidence that influenza vaccines are safe in asthma patients with and without egg allergy, British immunization guidelines152 now recommend administration of LAIV in the community to children from 2 years of age, including those with asthma, irrespective of egg allergy, unless they have severe or acutely exacerbated asthma. US and Canadian guidelines remain more conservative and still suggest that vaccines containing egg proteins (eg, LAIV) should not be used in children with egg allergy and/or asthma.153-155

9 ANTIVIRAL TREATMENT AGAINST INFLUENZA IN PATIENTS WITH ASTHMA

For asthma patients with suspected influenza infection, treatment with antiviral medication as early as possible, prior to laboratory confirmation of influenza, is currently recommended.156-160 As amantadine and rimantadine are limited by drug resistance, they have been replaced by neuraminidase inhibitors (NI). The currently marketed NIs are zanamivir and oseltamivir. However, postmarketing surveillance has revealed bronchospasm and worsening of lung function in a few cases when asthma patients were treated with zanamivir inhalation.161 Therefore, the manufacturer does now not recommend zanamivir for patients with chronic respiratory disease, including asthma.157, 158 Oseltamivir was not associated with any significant respiratory adverse effects and is recommended for treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza in children and adults with high-risk chronic conditions, including asthma.162-164 However, large-scale telephone surveys in the United States showed that having asthma, in contrast to diabetes, was not associated with increased rates of antiviral treatment of influenza cases.165

Data on the efficacy of NI in asthma patients162, 166-168 are limited. A benefit of oseltamivir treatment was found in children in an RCT that showed significantly improved pulmonary function and fewer AAEs.168 A meta-analysis, based on a single RCT, reported improved FEV1 after oral oseltamivir given to children with asthma and influenza infection, but no effects on peak flow or AAEs.169 Two recent systematic reviews found that oseltamivir relieved influenza symptoms in otherwise healthy children, but had no effect on children with asthma who have influenza-like illness,170, 171 a finding that is currently controversial.

As high rates of resistance limit the effectiveness of the currently available antiviral drugs, new NI (laninamivir, peramivir) and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor (favipiravir) are currently undergoing clinical trials.172 Laninamivir showed similar efficacy and safety to oseltamivir in the treatment of influenza in asthma patients.173

10 CONCLUSIONS

We observed significant variation in the reported rates of influenza detection among AAE episodes in both children and adults, with higher rates observed in the latter age group. This may be attributed to major differences in inclusion criteria, disease definitions, virus detection methodology, small population sizes and the limited number of available studies. Therefore, it is presently unclear to what degree influenza causes exacerbation of underlying asthma.

All European Union countries currently recommend influenza vaccination of people with asthma, with TIV being the most widely used vaccine. Nonetheless, vaccination coverage varies between regions and is significantly lower among children with asthma. Several factors and misbeliefs have been shown to predict nonadherence to influenza vaccination, while healthcare worker endorsement highly promotes vaccination. Major policy shifts and health campaigns may help in raising awareness and improve guideline implementation.

The limited immunogenicity data suggest that good seroprotection and seroconversion can be achieved in children and adults with asthma. However, higher vaccine doses may be required in elderly patients. Available studies suggest increased efficacy of LAIV in reducing influenza illness in children/adolescents with asthma compared to TIV, but do not provide evidence of efficacy of TIV in reducing influenza illness in patients with asthma concurring with a recent systematic review.18

There are some limited data to suggest that influenza vaccination reduces asthma-related morbidity in children in real-life settings, as has been concluded in another recent systematic review.139 The only data to suggest that vaccination may have a beneficial impact in adults with asthma are from studies of patients with long-term or high-risk conditions, not just asthma. The effectiveness outcomes of these studies are difficult to interpret due to lack of an agreed definition for asthma and/or influenza, and insufficient information on the type of vaccination used. Lack of randomization is also a limitation, as differences in the characteristics of those who do and do not receive the vaccine, such as disease severity and socioeconomic status, may independently impact on the likelihood of asthma morbidity, and analyses may not control for all these differences. Despite these limitations, population-based effectiveness studies are the only way to assess the impact of vaccination in real-life healthcare settings.

Inactivated influenza vaccines appear to be safe for people with asthma, and, provided they have low egg protein content (≤1.2 μg/mL), also for those with egg allergy. LAIV is also safe in asthma and egg allergy with the exception of severe or acutely exacerbated asthma, where LAIV cannot be given. Oseltamivir is the NI that is currently used in asthma. Although it has moderately beneficial effects on influenza illness in healthy people, there are insufficient data to determine its efficacy and effectiveness in people with asthma. However, novel NIs are currently in development.

11 RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE NEEDS

- People with asthma are at high risk of more severe forms of influenza, with increased hospitalization and admission at healthcare facilities, therefore:

- Education campaigns for both the general population and healthcare providers are needed to promote an increase in annual influenza vaccination, early case recognition, and consideration of early empirical antiviral therapy, and to reduce influenza-attributable healthcare utilization among patients with asthma.

- Large cohort and case-control studies using standardized definitions (for AAE), sensitive influenza detection methods, such as PCR, and comprehensive assessment of respiratory pathogens are necessary in both children and adults with asthma.

- There is a need to develop more internationally coordinated registries, for example, for Europe, that accurately collate vaccination status along with medical and socio-demographic details to assess the impact of public health interventions over time.

- Multiple sources of data must be used to record vaccination status (eg, self-reported as well as medical notes, vaccination card, or billing data).

- Targeted vaccination of children and at-risk groups is needed.

- Further studies of influenza vaccine immunogenicity, comparing healthy and asthmatic populations, are required to determine whether people with asthma have normal influenza vaccine responses or whether they require influenza vaccines with enhanced immunogenicity. The discovery and development of improved immune correlates of protection against influenza will enable more meaningful testing of vaccine immunogenicity.

- In view of the uncertainty around the degree of protection that influenza vaccination affords in people of all ages with asthma, further efficacy data need to be collected in this population. Data should be stratified by age and asthma severity, using adequately powered, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that compare both TIV and LAIV to nonvaccinated controls.

- Further studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in patients with asthma, but must be designed to minimize any risk of bias.

- Safety data in asthma with and without egg allergy are required for new influenza vaccines and, depending on egg protein content, for new LAIV batches.

- There is a need to collect more safety data on zanamivir in patients with chronic respiratory disease, and efficacy data on oseltamivir in children with asthma.

- Development and testing of new anti-influenza drugs among patients with asthma is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr Ron Hogg (OmniScience SA, Geneva, Switzerland) for his excellent medical writing services and ADME Osterhaus (affiliation) for his endorsement of this review as the chair of the European Scientific Working Group on Influenza (ESWI). The work was supported by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS