Practice and challenges for organ donation after medical assistance in dying: A scoping review including the results of the first international roundtable in 2021

Abstract

The procedure combining medical assistance in dying (MAiD) with donations after circulatory determination of death (DCDD) is known as organ donation after euthanasia (ODE). The first international roundtable on ODE was held during the 2021 WONCA family medicine conference as part of a scoping review. It aimed to document practice and related issues to advise patients, professionals, and policymakers, aiding the development of responsible guidelines and helping to navigate the issues. This was achieved through literature searches and national and international stakeholder meetings. Up to 2021, ODE was performed 286 times in Canada, the Netherlands, Spain, and Belgium, including eight cases of ODE from home (ODEH). MAiD was provided 17,217 times (2020) in the eight countries where ODE is permitted. As of 2021, 837 patients (up to 14% of recipients of DCDD donors) had received organs from ODE. ODE raises some important ethical concerns involving patient autonomy, the link between the request for MAiD and the request to donate organs and the increased burden placed on seriously ill MAiD patients.

Abbreviations

-

- DCDD

-

- donation after circulatory determination of death

-

- MAiD

-

- medical assistance in dying

-

- ODE

-

- organ donation after euthanasia

-

- ODEH

-

- organ donation after euthanasia from home

-

- OPO

-

- organ procurement organization (including donation coordinators)

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the first reported organ donation after euthanasia (ODE) in 2005, increasing numbers of patients requesting medical assistance in dying (MAiD) are asking to donate their organs after their death.s1 The development of ODE from home (ODEH) in 2017 might further improve the patient experience by eliminating the previous requirement for patients to encounter the hospital environment while conscious. ODE is of increasing importance for donors, representing up to 14% of donations after circulatory determination of death (DCDD).s2–s4 However, ODE is a complex procedure involving many unique ethical and logistical considerations and multiple stakeholders, including the patient and family, end-of-life care providers, and organ procurement organizations (OPO). To navigate these complexities, protocols have been developed to ensure ethical and compassionate end-of-life care and a positive donation experience for all concerned. This review aims to provide insight into international ODE practice by reviewing literature and holding stakeholder meetings on the practice of ODE, so as to advise patients, professionals, and policymakers in the context of their jurisdiction, aiding the development of responsible national guidelines.

2 METHODS

The research objectives were formulated from the review's aim as follows: first, to provide an outline of ODE practice and current MAiD and DCDD practice relevant to ODE, second, to identify issues affecting MAiD patients, providers, and other stakeholders in the context of ODE practice, and, finally, to formulate guidance for providers and other stakeholders on the issues identified.

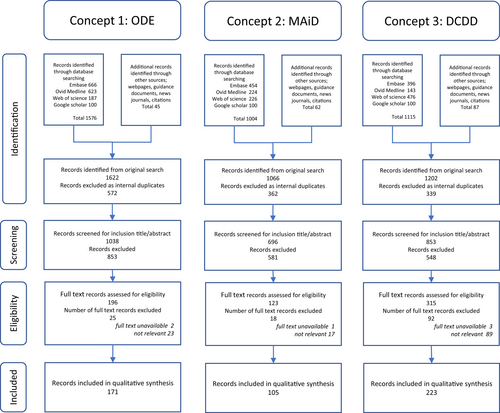

The objectives were researched in accordance with Arksey and O′Malley's scoping review methodology and the PRISMA-ScR directions (Data S1: research protocol).s5–s7 The literature search, covered bibliographic databases (Embase, Ovid/Medline, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and information identified through other sources (webpages, guidance documents, news journals, citations, policy documents, guidelines, and protocols). The databases were queried for English language papers published between 2017 and 2021 relating to the current practice of MAiD and DCDD where relevant to ODE and for papers in any language published between 1995 and 2022 relating to ODE by an experienced research information specialist (ID). Two reviewers (JM and HS) independently screened study titles and abstracts from initial search results and subsequently reviewed full texts. They included papers explicitly involving analysis or description of at least one of the review objectives. Literature concerning death definitions, death criteria and assessment methods, ethical justification of MAiD and DCDD, the dead donor rule, and the recipient care pathway was excluded.

To supplement the literature search, national stakeholder consultations involving the eight countries, where MAiD with intravenous substances is currently (2021) performed, were carried out, charting current practices of MAiD and DCDD relevant to ODE and of ODE itself. These were followed by the first international roundtable of ODE stakeholders (Roundtable participants: Data S2) during the 2021 WONCA international family medicine conference, during which stakeholders from the eight countries discussed practices and issues related to the research objectives.

The data obtained from the literature search and national and international stakeholder consultations were analyzed in accordance with the objectives and allocated to major subthemes identified from the literature (JM and HS). Data were presented in tables and a narrative synthesis of the results addressing the study objectives, progressing from basic subject information to an overarching discussion of issues on ODE. No institutional review board approval was required, as the project involved charting existing rules and practices. Some of the ODE incidence data quoted have been published in a letter to the editor to this journal in October 2021.185

3 RESULTS

3.1 Evidence analysis

A total of 2616 records (papers, abstracts, editorials, nonpublished articles, websites, guidance, and protocols) were identified up to February 6, 2022. After screening and eligibility assessment, 499 records were included in the narrative synthesis of the review (Figure 1). Thematic analysis yielded 10 clustered themes within the three main topics, MAiD, DCDD, and ODE: legislation, terminology, procedural aspects (protocols, eligibility, and safeguards), procedures in practice, and, specifically for ODE, desirability and appropriate care aspects. The key issues identified were death pathway concerns (consent, end-of-life care, guidelines, and access), MAiD in the DCDD death pathway, public trust, and providers' distress.

3.2 MAiD aspects relevant to ODE

3.2.1 Legislation and terminology

MAiD legislation has been discussed in many countries with varying levels of support and opposition.s8–s13 As of May 2022, 19 jurisdictions in eight countries have legislation permitting “MAiD by intravenous practitioner-administration of lethal substances,” the form of MAiD compatible with ODE (Data S5: Table B1). The main differences arise from the legals structure. Where MAiD is governed by the criminal code, the provider is only exempted from prosecution if MAiD is provided in accordance with appropriate care requirements. Where MAiD is decriminalized, postprocedural overview procedures are usually established. MAiD laws operate in conjunction with regional patient/professional medical treatment legislation to ensure appropriate end-of-life care alongside MAiD provision.

The legal act of practitioner administration of lethal MAiD substances with the intention of ending a patient's life at their voluntary, competent request was introduced in 2001 in the Netherlands, using the term euthanasia.s14,s15 Historical associations have caused reluctance to use this term universally, resulting in inconsistent use of terminology, with terms often encompassing both patient self-administration and practitioner administration of MAiD substances.s16 For the purposes of this review, “MAiD” refers to practitioner administration of lethal substances.

3.2.2 Procedural aspects

The aim of the “MAiD-patient care pathway” is a controlled, comfortable, and swift death, accomplished by circulatory arrest after induced acidosis, hypoxia, and cardiac depression, preceded by induced coma.s17,s18 MAiD legislation generally stipulates “reserved MAiD acts”, which may only be performed by the legal MAiD provider. These are administration of the MAiD substances and death declaration. The Netherlands,s17 Colombia,s19 and Spains20 have specific national guidelines, whereas other jurisdictions have protocols.s21–s30 Provision commences with an intravenous coma-inducing drug, followed by a paralytic agent and sometimes a cardioplegic agent. Typical coma inducers are thiopental and propofol. Nondepolarizing amino steroids are used as paralytic drugs and potassium chloride or bupivacaine as cardioplegic drugs.

The MAiD provider must declare death to bring the procedure to its legal conclusion. However, MAiD laws do not stipulate how death should be determined. Under general laws, death declaration is at the discretion of the attending physician.s31–s35 Where MAiD is governed by the criminal code, death is often required to be certified by a coroner.

The central eligibility criterion in all countries for MAiD is a required “symptom state” (Table 1). One of the main safeguards is that the MAiD provider must obtain and retain autonomous first-person consent following a patient-initiated request (Table 2). Autonomous means voluntary (competent and without coercion), well-considered, and having unbiased information. Information should be provided about potentially burdensome premortal interventions such as intravenous cannula placement and MAiD assessments such as mandatory peer consultation by an unknown independent physician. Moreover, information provision must take account of the narrative aspects of autonomy, so information should be discussed in relation to the patient's expectations, values, and wishes.s36–s45 Ongoing end-of-life discussions, including ongoing assessment of the validity of the consent and care planning by the MAiD provider, are an important part of quality end-of-life care.s46–s56 Regulations generally allow for healthcare professionals having conscientious objections to performing MAiD.

| Country/jurisdiction | Symptom state required | Specific medical conditions required | Life expectancy requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands1, 2 | Unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement | No | No |

| Belgium3, 4 | Unbearable physical or psychological suffering | No | Terminal or nonterminal |

| Luxembourg5 (RTS) | Constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering without the prospect of improvement | Incurable medical condition | No |

| Canada6-11 | Intolerable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person considers acceptable | A serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability, not solely psychiatric | No |

|

Australia |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Incurable disease that is advanced and progressive | <6 months or <12 months with neurodegenerative condition |

|

Australia Western Australia14 |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Incurable disease that is advanced and progressive | <6 months or <12 months with neurodegenerative condition |

|

Australia Tasmania15 |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Incurable disease that is advanced and progressive | 6–12 months criteria apply, but exemptions are possible |

|

Australia |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Medical condition that is advanced, progressive, and will cause death | <12 months |

|

Australia South Australia18 |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Medical condition that is advanced, progressive, and will cause death | <6 months or <12 months with neurodegenerative condition |

|

Australia New South Wales19 |

Suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner the person deems tolerable | Medical condition that is advanced, progressive, and will cause death | <6 months or <12 months with neurodegenerative condition |

| Spain20 | Constant and unbearable physical or psychological suffering | Severe and incurable illness or severe, chronic, and disabling condition | No |

| New Zealand21 | Unbearable suffering that cannot be relieved in a manner that the person considers tolerable | Incurable disease that is advanced and progressive | <6 months |

| Colombia22-26 (RTS) | Intense suffering with no other option for relief | No | Imminent death |

- Note: Eligibility criteria for MAiD that could potentially form part of ODE vary by jurisdiction.

- Abbreviations: MAiD, medical assistance in dying; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders.

| Jurisdiction | Independent consultation | External prior review | Reflection period required | Reserved MAiD acts only by | Coroner involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands1, 2 | 1 physician | No | No | Physician | Yes |

| Belgium3 | 1 physician (terminal patient) or 2 physicians (non-terminal patient) | No | 1 month if nonterminal patients | Physician | No |

| Luxembourg5 (RTS) | 1 physician, 1 person trusted by the patient, and 1 member of the patient's medical team | No | No | Physician | No |

| Canada6-11 | 1 physician or nurse practitioner | No | None if foreseeable natural death, 90 days if nonforeseeable natural death | Physician or Registered Nurseb | Differs by jurisdiction |

|

Australia |

1 medical specialista | Yes, permit | 9 days after the first request | Physician | Yes |

|

Australia Western Australia14 |

1 medical specialista | Yes, permit | 10 days after the written request | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

|

Australia Tasmania15 |

1 medical specialista | Yes, permit | No | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

|

Australia |

1 physician | Yes, permit | 9 days after the written request | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

|

Australia South Australia18 |

2 physicians | Yes, permit | 9 days after the written request | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

|

Australia New South Wales19 |

2 physicians | Yes, permit | 9 days after the written request | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

| Spain20 | 1 medical specialista | Yes, expert committee approval | 15 days after the first written request | Physician | Yes |

| New Zealand21 | 1 physician | Yes, countersigning | No | Physician or Registered Nurse | No |

| Colombia25, 26 (RTS) | 1 physician | Yes, expert committee approval | 15 days after external committee approval | Physician | No |

- Note: Required safeguards for appropriate/due care for MAiD that could potentially form part of ODE vary by jurisdiction.

- Abbreviations: MAiD, medical assistance in dying; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders.

- a The medical specialist should be specialized in the underlying condition.

- b In Quebec, only physicians are allowed to perform MAiD.

3.2.3 Practice

The 2020 incidence of MAiD, including self-administration, was 17 217 (Data S5: Table B2). Underlying medical conditions were predominantly oncological followed by neurological conditions. The practitioner administration mode of MAiD dominates. The time between MAiD induction and circulatory arrest averages 9 min, shortened by 1–2 min with the use of cardioplegia.s23,s27,s29,s30 Rare complications relate to venous access problems and the need for a second dose.s17,s18,s23,s27,s29,s30

Roundtable information

Stakeholders reported implementation of MAiD in Spain during this research, following its legalization in mid-2021. No official figures for Spain are available yet (June 2022).

3.3 DCDD aspects relevant to ODE

3.3.1 Legislation and terminology

Organ donation legislation focuses on consent rules, prohibition of organ trade, donor care, premortal assessments, and the obligation to uphold the “dead donor rule,” originally devised in the USA, which states that patients must be deceased at the time of organ retrieval and the act of retrieval cannot be the cause of death.s42,s57–s59 DCDD, the donation scenario compatible with ODE, is not provided in Colombia or Luxembourg.s60–s62

Consent for the DCDD donor pathway must be obtained and retained by an OPO representative and may be given in advance, deemed (via opt-out) or by a surrogate (in the absence of advance or deemed consent). In most jurisdictions, hospitals are required to notify the OPO of imminent deaths where organ donation may be possible.

DCDD is subdivided into uncontrolled (after unanticipated death) and controlled (after anticipated death) circumstances.s63 The latest DCDD classification refers to controlled DCDD (DCDD-III) as “planned withdrawal of life sustaining therapy with expected cardiac arrest” with the footnote “This category mainly refers to the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy decision. Legislation in some countries allows euthanasia and subsequent organ donation described as the fifth category.”s63

Typical controlled DCDD involves unconscious, intensive care patients, with pathologies that have not caused death by neurological criteria, but where further treatment is no longer considered beneficial to the patient.s64 Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy is then performed with death as a foreseen but unintended consequence, allowing procurement of organs.s65,s66 Rare conscious DCDD involves patients who are dependent on life-sustaining treatment but elect to cease treatment and donate their organs.s67–s70

Roundtable information

In Colombia, cultural aspects prevent DCDD or, consequently, ODE from being introduced soon. In Luxembourg, discussions about introducing DCDD are ongoing.

3.3.2 Procedural aspects

Three “patient care pathways” are distinguished in DCDD, each with their own objectives, ethical justification, practice, stakeholder motivations, and consent procedures as follows: the death pathway leading to the donating patient's death, the donor pathway leading to the donation of the patient's organs, and the recipient pathway leading to organ implantation (Table 3).s71–s78 It is important to note that the death and donor pathways involve the same dying patient.

| Patient care pathway | Procedure components | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary stakeholders | Primary objective | Death | Type of consent | MAiD | WLST | DCDD | WLST/DCDD | ODE | |

| Death pathway | WLST patient, family, and ICU treatment team | Ending nonbeneficial care under controlled circumstances with good end-of-life care | Foreseen but not intended | a | N/A | WLST pathway | N/A | WLST pathway | N/A |

| MAiD patient, family, and end-of-life primary care treatment team | Ending unbearable suffering by requested intentional death under controlled circumstances with good end-of-life care | Foreseen and intended | First-person | MAiD pathway | N/A | N/A | N/A | MAiD pathway | |

| Donor pathway | Donor patient, family, and donation team | Preserving good organ quality and optimal transplantation circumstances until death for the recipient's benefit | N/A | Deemed, advance, surrogate, first-person | N/A | N/A | Donor pathway | Donor pathway | Donor pathway |

| Recipient pathway | Recipient, family, and transplantation team | Delivering good transplantation care for the recipient's benefit | N/A | First-person | N/A | N/A | Recipient pathway | Recipient pathway | Recipient pathway |

- Note: Three “patient care pathways” are distinguished, each with their own ethical justification, consent procedures, and practice: the death pathway leading to the patient's death, the donor pathway leading to organ donation, and the recipient pathway leading to transplantation of donor organ(s). Several different pathways play a role within each of the procedures. To preserve autonomy in this ethically sensitive environment, they should intertwine as little as possible within the different procedures.

- Abbreviations: DCDD, donation after circulatory determination of death; ICU, intensive care unit; MAiD, medical assistance in dying; N/A, not applicable; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; WLST, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy.

- a When it is clear that treatment will not be medically effective and is not in accordance with the standard of care, the physician is not obliged to begin, continue, or maintain the treatment. To that extent, WLST is a medical decision. However, this decision should be inclusive, consultative, contemplative, and appropriately timed and preferably consensual with the family.

While practice varies, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy is generally initiated in the DCDD death pathway in intensive care or operating room by administration of sedatives/analgesics followed by withdrawal of vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation.s79–s82

The DCDD donor pathway involves premortal interventions for the recipient's benefit. Depending on which premortal interventions the country's legislation permits, these may include imaging, blood tests, invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, heparin administration, and changing the setting where death takes place.s66,s79,s83–s88 Relatively new are postmortal regional perfusion procedures.s83,s89–s104

Death, currently defined as the moment of “permanent death,” must be awaited before organ procurement, to uphold the dead donor rule in the DCDD donor pathway.s42, s105–s108 With DCDD, the moment of permanent death is defined as the moment when circulation to the brain ceases following cardiac arrest and chances of spontaneous return of circulation are very small.s65 Circulatory arrest assessment methods and the wait time after arrest, required to establish “permanent death,” vary internationally (Table 4). Related OPO regulations and targets vary too.s109–s113

| Jurisdiction | DCDD guideline since | Legally required death assessment method | Mandatory wait time | Donor death declaration by | Deceased donorsa | DCDD donorsa | Proportion of deceased donors via DCDD | DCDD donors hearta | DCDD donors lunga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands30-32 | 1996 | IABP | 5 min | 1 doctor | 15 | 9 | 61% | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Belgium30, 31, 33, 34 | 2021 | EKG or IABP | 5 min | 3 doctors | 24 | 9 | 42% | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Canada30, 31, 35-37 | 2006 | IABP or EKG | 5 min | 2 doctors | 20 | 5 | 27% | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Australia30, 31, 38, 39 | 2007 | EKG or IABP | 3 minb | 1 doctor | 18 | 5 | 30% | 0.8 | 1.5 |

| Spain30, 31, 33, 40 | 2012 | EC or EKG or IABP | 5 min | 1 doctor | 38 | 13 | 35% | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| New Zealand30, 31, 38 | 2012 | EKG or IABP | 3 minb | 1 doctor | 13 | 2 | 13% | 0.0 | 0.6 |

- Note: For DCDD, the required death assessment method and “wait time” after circulatory arrest before “permanent death” is established differ by country. The practice of deceased donation, DCDD donation, and specific DCDD organ procurement also varies significantly. In Colombia and Luxembourg, although MAiD is permitted, DCDD is not yet provided.

- Abbreviations: DCDD, donation after circulatory determination of death; EC, echocardiogram; EKG, electrocardiogram; IABP, invasive continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring; MAiD, medical assistance in dying; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia.

- a Actual donors in 2020 per million population in a country.

- b Since 2021, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (Anzics) Statement 2021 on Death and Organ Donation advises 5 min.41

Eligibility for DCDD is mainly determined not only by consent, donor criteria, and logistics but also by jurisdiction-specific circulatory death certification. The OPO representative must ascertain or obtain and retain consent for the DCDD donation pathway.s59 Where deemed or advance consent exists, this requirement is satisfied.s66,s114 In its absence, surrogate consent must be obtained from the family.

Premortal interventions and immediate postmortal procedures are justified for the recipient's benefit to optimize donor organ quality.s79,s83–s89,s115–s131 However, varying outcomes when evaluating premortal intervention benefit-to-harm ratios result in differences between provisions in different jurisdictions.s42,s66,s79,s84–s86,s114,s132,s133 Postmortal regional perfusion is under discussion in some jurisdictions, as it may pose death safeguard challenges or conflict with legal death definitions.s134–s145 For example, Australian legislation prohibits restoration of any circulation after death.s141 Healthcare professionals' conscientious objections to DCDD aspects are receiving increasing attention.s146–s149

3.3.3 Practice

DCDD incidence is increasing.s65,s150–s155 The period between starting the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy and permanent circulation arrest, which determines donor eligibility, varies from minutes to days (47% of DCDD cases meet the commonly applied 2 hours limit for donation eligibility) and is difficult to predict.s79–s81,s156–s161 Donation outcomes after DCDD are similar to outcomes following donation after neurological determination of death for kidneys, lungs, and pancreatic islets, but they are more variable for livers and hearts.s102,s140,s156,s162–s223

3.4 ODE/ODEH

3.4.1 Legislation and terminology

Current laws do not prohibit ODE, but do not mention the possibility either, and regulatory organs only make cautious statements, such as “Voluntary termination of life by means of euthanasia does not necessarily preclude organ and tissue donation.”1, 42, 43 Or, for ODEH, “The committee regards the procedure in principle as a viable route, provided that it does not impede a careful establishment of death.”44 This contrasts with the open support of “Right to Die” organizations, patient advocacy organizations, individual patients, and OPOs.45-55

The requirement for hospitals to notify OPOs of imminent deaths, in general, does not apply to MAiD patients, except in Ontario and Quebec in Canada where this is unclear.56-58 ODE-derived organs can only be allocated to jurisdictions where MAiD is permitted.53

In 2017, the acronyms ODE and ODEH were coined to refer specifically to the total process that combines MAiD and DCDD, preserving the eligibility assessments and safeguards for both these subprocedures but integrating them in a way that places the emphasis on caring for the MAiD patient and the ethical perspectives and considerations this entails.59, 60 This emphasis is what distinguishes ODE from conscious (or unconscious) withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy DCDD/DCDD-III or DCDD-V procedures. ODE should also be clearly distinguished from “living donation in anticipation of MAiD,” which has no regulatory or professional endorsement, and “MAiD by removal of organs in an anesthetized patient,” which constitutes homicide.61-72

Roundtable information

All participants strongly supported the development of ODE and regarded ODE/ODEH as good universal terms for general adoption, as they are straightforward but indirect and have neutral semantics.

3.4.2 Procedural aspects

The major difference between ODE and typical DCDD-III (or withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy/DCDD) is the MAiD act in the DCDD death pathway, resulting in the foreseen and intended death of a conscious patient in the donor pathway, significantly affecting both pathways. ODEH involves additional deployment of a mobile team and mid-procedure transport.73, 74

The Netherlands published a national guideline, based on a 2-year Delphi-like multistakeholder process organized by the Dutch Transplant Foundation (Table 5). Key considerations were peer-reviewed, published, and presented to the Dutch house of representatives.59, 83 The guideline has two parts, consisting of a practice manual and background information, and replaces earlier manuals. It focuses on the MAiD patient in the death pathway during four phases: (1) decision-making about the end of life, (2) preparations for the end of life, (3) end of life, and (4) organ donation and family grief counseling. The 2022 update includes the recommendation for the invasive blood pressure measurement and the ODEH option.

| Jurisdiction | National terminology | Acronym | Guideline | Consent approach | Death certification MAiD/DCDD | Coma inductor | Paralytic agent | Cardio-plegics | Death assessment | Wait time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The59, 75, 76 Netherlands | Organ donation after euthanasia | ODE | 2017 National guideline | Patient initiated | MAiD provider, advised by an intensivist | Thiopental/propofol | Roc | No | IABP | 5 min |

| Belgium34 | DCD-V | DCD-V | 2021 Consensus statement | Patient initiated | MAiD provider and two other physicians | Thiopental/propofol | Roc | No | IABP | 5 min |

| Canada77, 78 | Organ tissue donation and transplantation after MAiD | OTDT after MAiD | 2019 National Guidance | Patient and doctor initiated | MAiD provider and another physician | Propofol | Roc | Differs | IABP, ECG | 5 min |

| Spain (RTS)a,79-82 | Donación tras prestación de ayuda para morir o donación tras eutanasia | None | 2022 National protocol | Patient initiated | MAiD provider, advised by another physician | Propofol/ Thiopental | Roc | No | IABP, ECG, EC | 5 min |

- Note: Summary of the procedural aspects of ODE. Death declaration is more elaborate with DCDD, as the MAiD provider must receive advice on “permanent death” and sometimes more than one physician is required.

- Abbreviations: EC, echocardiogram; EKG, electrocardiogram; DCD-V, donation after circulatory death variant V; IABP, invasive continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring; MAiD, medical assistance in dying; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; OPO, organ procurement organization; OTDT, organ and tissue donation and transplantation; Roc, rocuronium; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders.

- a In Spain, a national protocol is expected in late 2022. In the meantime, a directive on “Summary OPO recommendations on donation after MAiD” was issued in July 2021 (RTS).

Canada published national policy guidance, based on a 2-day forum organized by the Canadian Blood Services and operating together with existing protocols.77, 78, 84, 85 Key considerations were peer-reviewed and published. The primary perspective is the DCDD donor patient pathway, with MAiD regarded as an end-of-life intervention with five steps: (1 + 2) MAiD request and determination of eligibility, (3) OPO referral and DCDD suitability assessment, (4) MAiD patient approach by OPO representative for consent and donor testing, and (5) hospital admission for premortal interventions and MAiD provision. Recent summits were held regarding the 2021 changes to MAiD legislation and the ODEH option.

Belgium published a national DCDD consensus by an expert group, organized by the Belgian Transplantation Society.34 A chapter is dedicated to ODE, with the primary perspective of the donor pathway and focusing on the importance of preserving MAiD patient autonomy. More specific local protocols have been developed.86

Spain commenced ODE practice following the legalization of MAiD but has no official publications yet.79-82

Roundtable information

In Spain, the National Transplant Committee established a working group in 2021 to develop an ODE/ODEH national protocol, which is currently subject to stakeholder consultation. In advance of this protocol, the National Transplant Organization released “recommendations for donor coordinator teams” for dealing with current requests. Key elements include MAiD pathway consent must precede donor pathway consent; MAiD plans take precedence over organ donation; patients can revoke donation consent at any time; organ donation may only be incorporated into the end-of-life process if consistent with the patient's wishes; and the patient's dignity and comfort must be ensured during the end-of-life process.

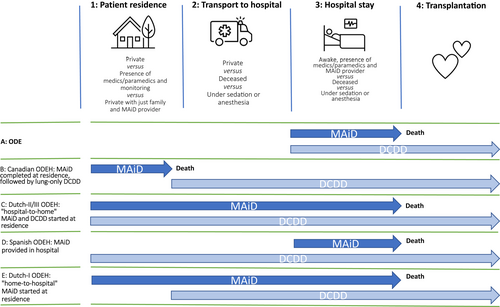

3.4.3 ODEH models

No ODEH guidelines have been published yet, but several models exist (Table 6 and Figure 2). With the Dutch model, an anesthesiologist/intensivist waits near the patient's preferred dying location. The procedure is initiated with midazolam sedation by the MAiD provider, with only the patient and their loved ones present for final farewells. After sedation, the anesthesiologist/intensivist is alerted and converts sedation to anesthesia with propofol, intubation, and the application of tidal ventilation. Subsequent continuous propofol administration is provided during transport and physiological conditions are maintained until MAiD death occurs in the hospital. Premortal interventions are performed in the hospital before MAiD administration. Death declaration by the MAiD provider according to permanent death criteria concludes the MAiD procedure and multiorgan donation follows. If mechanical, ventilated, or organ-perfusion support unexpectedly fails during transport, the MAiD substances are administered immediately, initiating uncontrolled but comfortable death. Three variants have been performed. The first (Dutch-I) variant differs from II and III by the absence of medic/paramedic attendance during farewells, the absence of vital monitoring when the patient is still conscious and subsequent transport with controlled anesthesia (variant III only).

| Modes, country, and year of the first provision | Location | Death | First-person consent | Organ donation | Monitoreda sedation | Sedation orb anesthesia | Hospital staff present outside the hospital | MAiD provider present during transport | Time from injection to permanent circulation arrest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DCD-III/WLST32 unconscious “regular” |

WLST provided in the hospital | Fn | No | M | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | Variable |

|

DCD-III/WLST32 conscious competent |

WLST provided in the hospital | Fn | Yes | M | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | Variable |

|

Belgium (2005)87 |

MAiD provided in the hospital | Fi | Yes | M | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | <7 |

|

ODEH Canadian74 Canada 2019 (RTS) |

MAiD provided at home, transport of the body | Fi | Yes | S | No | N/A | Yes | No | Variable |

|

Dutch-I |

MAiD initiated at home and completed in the hospital | Fi | Yes | M | No | Anesthesia | Yes | Yes | <7 |

|

ODEHd Dutch-II Netherlands |

MAiD initiated at home and completed in the hospital | Fi | Yes | M | Yes | Anesthesia | Yes | Yes | <7 |

|

ODEH90 Dutch-III Netherlands 2019 |

MAiD initiated at home and completed in the hospital | Fi | Yes | M | Yes | Sedation | Yes | Yes | <7 |

|

ODEH (RTS) Spain 2022 (RTS) |

MAiD provided in the hospital | Fi | Yes | M | Yes | Sedationc | Yes | No | Variable |

- Note: Organizational aspects of ODEH compared with DCDD and ODE.

- Abbreviations: DCD-III, donation after circulatory death variant III; Fi, foreseen and intended death; Fn, foreseen but not intended death; M, multiple organ donation; MAiD, medical assistance in dying; N/A, not applicable; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; ODEH, organ donation after euthanasia from home; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders; S, single organ donation.

- a Sometimes vital monitoring is present during the initial sedation, while the patient is still conscious.

- b During transport the patient can be given sedation with sedatives or controlled anesthesia with propofol.

- c In Spain, sedation and analgesia prescribed by the attending physicians from the out-of-hospital transferring services are given according to standard practice. If the physician believes that the patient may become unstable after sedation, they will intubate and ventilate the patient under deep sedation during transportation to the hospital, where the patient will receive MAiD and DCDD.

- d Personal communication (Wilson Fareed Abdo, UMCN, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, June 6, 2022).

With the Canadian model, a respiratory therapist and a physician wait close to the patient's preferred dying location. After MAiD substance administration at this location, the body is moved to the nearby ambulance, where EKG and apnea are monitored for 5 min. Death certification by the MAID provider and the second physician according to permanent death criteria concludes the MAiD procedure. After intubation and another 5-min waiting period, a nonperfused, in situ lung preservation technique is applied and transport is initiated. At the hospital, lung retrieval is performed.

Roundtable information

ODEH has already been performed in Spain, but not reported. The physician responsible for transport provides sedation and analgesia to the patient after final farewells at their home. A mobile intensive care unit then transfers the patient to the hospital, where the MAiD provider administers lethal medication. Following death certification by the MAiD provider, multiorgan retrieval takes place.

3.4.4 Eligibility and safeguards

Aside from logistical feasibility, eligibility for ODE/ODEH coincides with eligibility for MAiD and DCDD. The main safeguards involve the independent provision and maintenance of first-person consent for both MAiD and DCDD. To safeguard autonomy, many jurisdictions prohibit or discourage OPO/physician-initiated DCDD consent approaches or directed donation with ODE.59, 77, 91-98

Safeguarding end-of-life experience for MAiD patients in the ODE context requires active monitoring, given the potential for changes to the benefit/harm balance with these, sick, vulnerable patients, unlike unconscious withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy patients. Examples include burdensome assessments during their final days of life, painful interventions, the presence of unknown healthcare teams during MAiD, a different setting for MAiD, changes to the family's experience, and bereavement due to the removal of the body for several hours.59, 77, 92, 95, 99-116

The Dutch guideline incorporates choices about varying levels of premortal intervention burden as an explicit part of the donor pathway consent process, with the patient deciding the level of burden they wish to endure and OPO representatives then deciding which organs can be procured based on the premortal interventions appropriate to this level of imposed burden.59 In contrast to the regular approach of presenting premortal interventions and the promise of higher organ yield, this diminishes the risk of insufficiently well-considered compromises to the end-of-life experience.59 The Canadian guidance states “Based on their own comfort and preferences over how they wish to spend their last days, they may have questions and decline some investigations or donation interventions.”77 With ODEH, some burdens and potential distress are reduced compared with ODE (Table 7).

| Donor | Donor | Donor | Family | OPO professional | OPO professional | MAiD professional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures | Conscious donor encounters hospital environment on the final day | Conscious donor encounters OPO representatives on the final day | Awareness of PMIs on the final day | Family encounters hospital environment on the final day | OPO representative encounters conscious donor on the final day | Deployment of OPO representatives outside the hospital on the final day | MAiD professional encounters hospital environment on the final day |

| DCD-III/WLST32 unconscious “regular” | No | No | Reduced | Yes | No | No | N/A |

| DCD-III/WLST conscious | Yes | Yes | Standard | Yes | Yes | No | N/A |

| ODE34, 59, 77, 87 “classic” | Yes | Yes | Standard | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| ODEH Canadian74 (RTS) | No | No | Standard | Optional | No | Yes | No |

| ODEH60, 73, 88, 89 Dutch-I | No | No | Reduced | Optional | No | Yes | No |

| ODEH117 a Dutch-II | No | Yes | Reduced | Optional | No | Yes | No |

| ODEH90 Dutch-III | No | Yes | Reduced | Optional | No | Yes | No |

| ODEH Spain (RTS) | Yes/No | Yes/No | Reduced | Optional | Yes/No | Nob | Yes |

- Note: Sources of potential distress within the different procedures may originate from conscious and aware encounters by patients and healthcare providers. Awareness of PMIs is reduced when performed with unconscious patients.

- Abbreviations: DCD-III, donation after circulatory death variant III; DCDD, donation after the circulatory determination of death; N/A, not applicable; MAiD, medical assistance in dying; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; ODEH, organ donation after euthanasia from home; OPO, organ procurement organizations; PMI, premortal intervention; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders; WLST, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy.

- a Personal communication (Wilson Fareed Abdo, UMCN, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, June 6, 2022).

- b In Spain, the MAiD provider is not involved in the transportation of the patient.

Reappraisal of the benefit/harm ratios of premortal interventions with ODE led to the removal of the requirement for potentially painful invasive blood pressure monitoring for death assessment in Canada, unlike the Netherlands, where the same discussions resulted in this requirement being re-emphasized.44, 77 With ODEH, invasive blood pressure measurement is not burdensome as the patient is unconscious.

Concerns have been expressed regarding the use of sedatives during mid-procedure ODEH transport as, unlike propofol anesthesia, these do not guarantee complete loss of awareness.88, 118

Healthcare providers' conscientious objections are a familiar topic within MAiD care pathways, but less common in DCDD death pathways, typically performed with the less controversial withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy, and jurisdictions are developing protocols for this scenario.59, 77

Roundtable information

The draft Spanish recommendations on ODE mention “prioritization of MAiD plans over organ donation” to prevent most end-of-life compromise. Stakeholders report that healthcare providers' conscientious objections are an active discussion topic.

3.4.5 Practice and donations

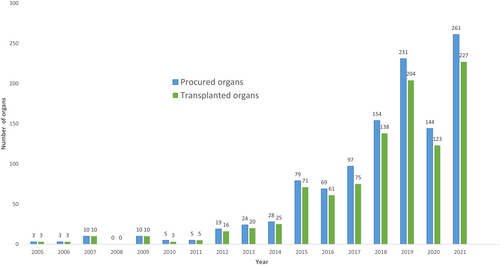

By 2021, ODE had been provided 286 times and ODEH 8 times, with the incidence rising annually (Table 8). The main underlying conditions were neurodegenerative and the most common MAiD provider was the general practitioner.

| Jurisdiction | First provision | ODE incidence up to and including 2021 | ODE incidence in 2021 | ODEH incidence up to and including 2021 | ODE incidence relative to DD | ODE incidence relative to DCDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium87, 119-125 | 2005 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 10/312 (3%) (2019) | 10/206 (5%) (2019) |

| The Netherlands48, 90, 131-133 | 2012 | 86 | 13 | 3 | 14/250 (6%) (2019) | 14/147 (9%) (2019) |

| Canada45-47, 54, 134, 135 (RTS) | 2019 | 136 | 49 | 5 | 33/762 (4%) (2018) | 33/230 (14%) (2018) |

| Spain (RTS) | 2021 | 7 | 7 | 0a | 7/1905 (<1%) (2021) | 7/662 (1%) (2021) |

| Total | 286 | 69 | 8 |

- Note: ODE/ODEH incidence, absolute and relative to deceased donation and DCDD. Due to COVID, no ODE took place in Belgium in 2021 (RTS). Contrary to popular belief, ODE is not provided in Luxembourg and Colombia (RTS). For relative incidence values, pre-COVID data were used for better interpretation. Data provided by Eurotransplant statistics analysis for ODE, 2012–2021, Nederlandse transplantatie stichting (Sonneveld), the Netherlands; Eurotransplant statistics analysis for DCD-V, 2005–2021, Transplant Centre University Hospitals Leuven (Desschans), Belgium; Statistical analysis for OTDT after MAiD, 2005–2021, Canadian Blood Service (LaHaie), Canada (excluding Québec), and Transplant Québec (Dupras-Langlais), Québec, Canada; and Statistical analysis for ODE, 2021, Organización Nacional de Trasplantes (Pérez Blanco), Spain.

- Abbreviations: DCDD, donation after the circulatory determination of death; DD, deceased donation; ODE, organ donation after euthanasia; ODEH, organ donation after euthanasia from home; RTS, information provided by roundtable stakeholders.

- a Spain started provision in 2020 and the first three occurrences of ODEH were in 2022 (data up to April 2022) (RTS).

The quality of ODE donor organs is at least comparable to organs retrieved following the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy/DCDD and even donation after neurological determination of death (Data S4).

This—perhaps not universally anticipated—similarity in organ quality may be due to earlier methodological bias in ischemia assessment, minimal lasting effects of MAiD substances, and underlying conditions and specific—pathophysiologic—effects related to donation after neurological determination of death. Experience with ODEH is limited, but there is no logical reason to assume inferiority.

Since 2005, 1136 organs have been donated, 988 of which were transplanted, to approximately 837 recipients resulting on average in 2.9 recipients receiving organs per ODE patient (Data S5: Tables B3/B4 and Figure 3).

3.4.6 Desirability and appropriate care

Eligibility criteria and safeguards should ensure the highest quality of care with medical procedures. The remaining challenges mentioned in the literature can be characterized as issues of desirability and appropriate care (also called due care).136

The first ODE patient from Belgium told her GP in 2005: “I want to donate my organs. That way, I'll still be doing something good with this body of mine.”119 A Dutch ODEH patient expressed the same sentiment in 2017: “I want to donate to be able to do something good with the diseased body that's also leading me to choose euthanasia.”48, 89 In 2019, a Canadian ODEH patient explained that “he wanted to save another person's life after seeing so many traumatic deaths on the job (being a policeman),” and an ODE patient “…kept pushing even though she wasn't able to speak (anymore).”45, 46 Many more patients have voiced this desire publicly.45-47, 52, 137 These patients appear to have a dual perception of their bodies: instrumental as an object for donation and manifesting as a subject in the world.138-140 This can be reformulated as “the severely diseased body that causes the loss of hope and suffering is, at the same time, a source of something good,” perhaps linked with the idea of a “body project,” indicating the importance of the body as a site for personal preferences and decisions.48, 59, 119, 139, 141, 142 Such a “body project” may contribute to the donor's moral identity, in which they see the body as a useful source for others in need, expressing something about their moral character.139, 143 For end-of-life care stakeholders, the desirability of ODE coincides with the last wishes of the MAiD patient.46, 144, 145 Recipients and their stakeholders welcome the addition of donor organs. Public opinion is still evolving, but a Canadian survey has shown strong support for ODE.77 The main concerns about appropriate care center around two issues: the potential for the MAiD decision and the organ donation decision to influence one another and premortal interventions and their effect on the MAiD patient's end-of-life experience in the donor pathway (Data S5: Table B5).

Roundtable information

All participants acknowledged that the practice of ODE has overwhelmingly been driven by MAiD patients wishing to donate.

4 DISCUSSION

The current practice of ODE, and of MAiD and DCDD where relevant to ODE, is outlined in Section 3. The main issues and concerns identified are addressed here.

4.1 Donor pathway concerns

4.1.1 Consent

Resolving the consent issues in ODE starts with the recognition that the death pathway and donor pathway in DCDD involve the same potentially influenceable MAiD patient. There are several reasons why it is inherently impossible to adhere to the strict principle of separation of care pathways, as advocated in the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy/DCDD practice to minimize the risk of influence.91, 96, 110, 146-149 With the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy/DCDD, an unconscious patient's decision to donate is not subject to influence if deemed/advance consent is present. In its absence, approaching the family to obtain surrogate consent is explored. Besides, within the death pathway, the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy decisions with an unconscious patient is inherently nonpatient-dependent. The only potential for influence on this decision lies in the interaction between the patient's intensive care team/surrogate decision-maker and OPO representatives.

With ODE, there are multiple opportunities for considerations in one pathway to influence a decision made in the other. Current guidance indicates that the MAiD decision should precede discussion of organ donation and only after consent for MAiD is confirmed may the OPO representative approach the MAiD patient to obtain and retain consent for the donor pathway. But, from that moment on, the potentially influenceable patient (in contrast to the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy patient) not only decides on providing and maintaining donor pathway consent but also on maintaining the MAID death pathway consent. There is an inevitable intertwining of care pathways and ongoing interactions with the OPO representatives/donor coordinator might influence the donor to maintain consent for MAiD and donation. The MAiD provider needs to understand the dynamics of human decision-making and the inherent psychological processes of altruism and social desirability that could uniquely influence the MAiD consent process in the context of ODE (but not when MAiD is the only consideration).146, 150-154

First-person consent with ODE respects the interests of autonomy better than deemed or surrogate consent. Some ODEH modes enhance this, as patient care pathways do not intertwine on the final day while the patient is still conscious.73, 74, 154

To anticipate the pathway interaction risks, the Dutch guideline advocates minimal contact between OPO representatives and the conscious MAiD patient.59 Communication should be confined to providing donor pathway information, without the aim of conversion to ODE or retaining consent for DCDD, and MAiD should not be discussed at all.111 With ODE, end-of-life care should remain the responsibility of the primary patient care team. From this perspective, labeling the donor consent process as “end-of-life care” could lead to coercion-sensitive confusion. The Canadian guidance advocates specialized OPO representatives to deal with ODE practice.77

Roundtable information

Forum experts expressed concerns about unsolicited approaches to obtain donor pathway consent by treating physician or OPO and the idea of “directed donation” in ODE because of the potential to exacerbate the influence of donation pathway considerations on the MAiD decision. Some experts added that no information should be given on organ allocation, due to the risk that knowing how many people their organs could help will prevent the MAiD patient from feeling absolute freedom to change their mind right up until the last time they are asked whether they wish to proceed, just before substance administration.

4.1.2 End-of-life care

For the MAiD patient in the donor pathway, unlike the unconscious withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy patient, every premortal intervention is potentially burdensome. The literature agrees that for valid donor pathway consent, all premortal interventions for the recipient's benefit must be discussed with the MAiD patient in terms of their necessity and impact on the end-of-life experience, bearing in mind the patient's aims and wishes for the end-of-life experience. Every premortal intervention should be carefully analyzed to establish its benefit/harm ratio. With some ODEH modes, the burden is diminished, as most premortal interventions can be performed while the patient is anesthetized.

Roundtable information

Some experts advocated, “always ask the patient (which premortal interventions they want), they will tell you what they want,” but others added, “this only works when the patient is first provided with transparent and unbiased information (on premortal interventions).” Another issue considered was how far one should push the limits of DCDD practice to adapt to the addition of MAiD. It was felt that failing to adapt premortal interventions as much as possible would create an “all or nothing” model that would put patients under pressure and invariably fail to respect patient autonomy, either by forcing them to accept premortal interventions they do not want or by denying them the opportunity to donate. Ultimately, participants felt that the focus should be on the obligation to satisfy the patient's wishes when they are feasible and valid, and organ yield as a secondary benefit.

4.1.3 ODE guidelines

ODE is an exceptional procedure, presenting legal, ethical, and operational challenges and requiring dedicated guidance that will gain and retain society's confidence. If protocols are diffuse in their aims or burdened by earlier habits and ways of thinking, quality of care could be compromised and trust lost.96, 153, 155 Professionals need to recognize each other's different roles and interests and coordination of this should be incorporated in a guidance document. Separate classifications of ODE-related DCDD (DCDD-V) and ODE-related MAiD aid this objective.156, 157

Roundtable information

“Do we only need guidelines to fill up the gaps between laws?” was asked. The conclusion was yes because the laws do not prohibit ODE but do not provide legal certainty in performance either; and no, as both MAiD and OPO providers need to make considerable changes to their usual practice in order to implement ODE.

4.1.4 Death

Upholding the dead donor rule and the need for viable organs led to the “permanent” death definition within DCDD. However, permanent does not equal irreversible, leaving a window for rare, undesired autoresuscitation.158-165 Also, dying sometimes takes longer than expected. From the perspective of the MAiD-patient care pathway, which focuses on swift and comfortable death, the occurrence of delayed death or autoresuscitation would suggest an insufficient first dose and a second dose should follow. In the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy patient care pathway, focused on ending mechanical, ventilated, or organ-perfusion support when no longer considered beneficial to the patient while preventing discomfort, this occurrence signifies a prolonged dying phase and circulatory arrest (or its return) must be awaited. In the DCDD donor patient care pathway, focused on donor organ care without harming the donor, this occurrence also signifies a prolonged dying phase and death must be awaited (or awaited again) for the dead donor rule to be fulfilled before procurement can commence. Within ODE, the most feasible option in the event of delayed death seems to be for the MAiD provider to administer a second dose of MAiD substances after a predefined fixed period and for the OPO providers to wait for permanent death to occur (or reoccur).

Roundtable information

Participants felt that diminishing undesired occurrence strengthens the case for use of cardioplegics, in the interests of both MAiD patient and recipient.

4.1.5 Access

The main limitation to ODE access is the limited number of jurisdictions (19) allowing practitioner-administered MAiD.79, 166-170 The MAiD “stopcock infusion procedure,” available in some jurisdictions42 and involving the patient self-administering the intravenous MAiD substances, might be acceptable in more jurisdictions as it qualifies as assisted suicide and could be used with ODE.

DCDD access is also limited (17 countries).171 DCDD incidence as a proportion of total deceased donations varies significantly by jurisdiction and further acceptance might increase access.

ODE incidence in jurisdictions permitting MAiD was 37 in 2020, while MAiD incidence was 16 977. With an estimated 10% eligibility, this would put utilization at roughly 2%, possibly due to a lack of familiarity and acceptance, the need for guideline development, and implementation.172

Regional ODE access aspects include imminent-death eligibility criteria for MAiD in New Zealand and Australia, the prereview requirement in Spain, and the legal default of self-administration in some Australian jurisdictions.

Roundtable information

The slow rise in ODEH access is probably related to the extra effort and logistics involved. Changes to standard performance take time to be accepted and embraced but, here again, patient demand probably becomes an important driver.

4.2 MAiD in the DCDD death pathway

One of the primary MAiD eligibility criteria is “unbearable suffering with no prospect of relief,” and the MAiD provider must be able to demonstrate this convincingly. A donation as a primary reason, that is, MAiD patients thinking that they are more valuable dead than alive, would be unacceptable and harm the MAiD cause. 112, 146, 150-152, 173

4.3 Providers' distress and conscientious objections

Appropriate care involves safeguards to deal with professional distress and conscientious objections by healthcare providers. Within typical withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy/DCDD, OPO representatives already describe approaching family members as the most stressful part of their job, which might be exacerbated by interactions with the conscious MAiD donor.174 Concerns can extend to all involved.175-177 Literature emphasizes the importance of healthcare providers participating voluntarily in the ethically sensitive environment of ODE.111, 174, 176, 178-184

Roundtable information

Participants strongly supported voluntary involvement in the procedure.

4.4 Public trust and acceptance

Appropriate care with respect to public trust involves obtaining and maintaining society's support for a procedure like ODE. Society must be confident that the principle of nonmaleficence dominates medical practice and that the patient's needs always take priority over any organs they might donate after death.126, 155 If a public misperception arises that ODE is aimed at increasing organ procurement, this confidence will be rapidly lost.71, 127-129

Roundtable information

To ensure that ODE remains ethically justifiable, the procedure should remain a MAiD patient care–driven process, with the maximum adaptation of donation processes and minimal intrusion and impairment for end-of-life care.

4.5 Limitations and strengths

As is inherent with a scoping review compared with a systematic review, the quality of the studies included was not assessed and the synthesis is descriptive. Our search algorithm included various terms previously used to describe ODE, but others may exist. While our review included any article in any language on ODE, our search was conducted using English terms. Presubmission of the protocol was to local authorities and not as a journal submission, as is becoming more routine.

The review had a broad and inclusive search strategy, with evidence screened by two investigators at both titles/abstract and full-text levels. National stakeholder meetings and an international roundtable enabled consultation with stakeholders of all countries permitting practitioner-administered MAiD to validate the search results. Together with an interactive manuscript review, this all contributed to the validity.

5 CONCLUSIONS

As of 2021, ODE had been provided 286 times (including ODEH) in Belgium, the Netherlands, Canada, and Spain, donating 1131 organs to 837 recipient patients. Incidence is rising and ODE now represents a significant proportion of DCDD donations. MAiD and donor stakeholders regard ODE as desirable but emphasize the need for guidance and safeguards for appropriate care. Challenges for providers are obtaining autonomous, independent first-person consent to MAID and DCDD and retaining this until provision and incorporating the varying jurisdictional requirements.

This comprehensive review of ODE/ODEH and MAiD/DCDD practice in relation to ODE/ODEH, and the issues involved may assist patients, professionals, and policymakers and aid the development of responsible protocols and guidelines.

5.1 Research gaps and further actions

This review shows several topics requiring further research (Data S5: Table B6).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JM and HS: Conceptualization and methodology design, literature search, data collection and data analysis, project administration, data interpretation and writing, and review and editing. DR, AN, BD, KW, AH, AP, and BD: Investigation, data collection and analysis, data interpretation and writing, and review and editing. JD, GO, and ID: data interpretation and writing and review and editing. All authors and roundtable participants read and approved the final manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

The tables providing background information on ODE are preceded with the letter B and contained in Background Tables B1-B6.

The references up to paragraph 3.4 and for the background tables, which largely provide background information on ODE, are preceded with the letter s and listed in Data S3.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created during this review.