Association of chemotherapy dose intensity and age with outcomes in patients with Ewing's family sarcoma

Abstract

Background

Ewing's family sarcoma (EFS) is an aggressive malignancy with a peak incidence in adolescents. Multimodal treatment involves surgery and/or radiotherapy, and chemotherapy typically with VDC/IE (vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide). There is a paucity of data for the treatment of adults, with protocols extrapolated from the pediatric setting. This study aimed to assess patterns of care, chemotherapy tolerability across age groups, and outcomes from four Australian sarcoma centers.

Methods

ANZSA ACCORD sarcoma database and medical records were used to identify and collect data of patients aged ≥ 10 years with EFS who received VDC/IE between 2010 and 2020. Survival outcomes were analyzed based on chemotherapy received dose intensity (RDI). Clinical predictors of RDI were explored using logistic regression.

Results

Of 146 patients with EFS, 76 received VDC/IE. The majority had localized disease (65%). Seventy-one percent completed scheduled chemotherapy, with some requiring dose reduction (29%), delay > 7 days (65%), or cycle omission (4%). Hematological toxicity was the main reason for dose reduction/delay. Fifty-seven percent patients achieved an acceptable RDI ≥85%. Compared to those aged 10–19, the odds ratio for acceptable RDI aged 40–59 was 0.20 (95% CI 0.04−0.86, p = 0.04). RDI was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival, after accounting for age, gender, Ewing's type, primary site, and stage (adjusted HR 0.25 [95% CI 0.10−0.63], p = 0.004).

Conclusion

Survival outcomes in EFS were associated with chemotherapy RDI. Older adults more commonly required dose reduction or early cessation of treatment due to toxicity. VDC/IE chemotherapy should be carefully tailored in adults > 40 years.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ewing's family sarcoma (EFS) is a rare and aggressive small round blue cell malignancy arising from either bone or soft tissue. The overall incidence for all ages is one case per million, reaching a peak incidence of 10 cases per million in the second decade of life.1, 2 Diagnosis is usually confirmed by identification of t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation which fuses the EWS gene on chromosome 22 with the FLI1 gene on chromosome 11.3

Treatment protocols for EFS are multimodal and typically involve intensive multiagent chemotherapy combined with surgery and/or radiation therapy to the primary tumor site.1, 2, 4, 5 This multidisciplinary approach has resulted in improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), particularly for those with localized disease.6, 7 The Euro Ewings 2012 trial randomized patients with localized or metastatic disease to receive either VDC/IE (vincristine [V], doxorubicin [D], and cyclophosphamide [C], alternating with ifosfamide [I] and etoposide [E]) or VIDE (vincristine [V], ifosfamide [I], doxorubicin [D], and etoposide [E]). VDC/IE, compared to VIDE, was associated with superior event-free survival (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.61−0.95) and OS (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.42−0.96) without excess toxicity.8

For many decades, it has been recognized that the relative or received dose intensity (RDI) of chemotherapy—which considers both the total dose of chemotherapy and the time interval for administration to calculate the ratio of delivered to planned dose intensity—correlates with oncological outcomes, including response rate and OS in both adjuvant and metastatic settings, across tumor types.9, 10 RDI has also been confirmed as an important prognostic factor in sarcoma, with reduced RDI secondary to poor tolerability or side effects requiring dose reductions or treatment delay associated with inferior outcomes.2, 4, 11-14

Chemotherapy choice for adult patients is largely extrapolated from the pediatric and adolescent setting, with large, randomized trials either excluding older adults, or containing only a small proportion of patients over 40 years of age, thus restricting the interpretation of results.15-18 Real-world data in the adult population, mostly derived from small retrospective case studies, show conflicting results regarding the tolerability and toxicity profile of these pediatric regimens.2, 4, 5, 7, 11, 19-21 As a result, there is a paucity of data regarding patterns of care and outcomes for older individuals. The aim of this study was to assess patterns of care, chemotherapy tolerability across different age groups, and outcomes across four Australian sarcoma centers. We hypothesized that there would be an association between lower RDI of chemotherapy and poorer disease-related outcomes in older adults.

2 METHODS

2.1 Patients

Patients were a subset of adult patients from the Australian Comprehensive Cancer Outcomes and Research Database (ACCORD), and pediatric patients identified from the medical records of one pediatric hospital. ACCORD is a national electronic resource capturing clinical data and treatment outcomes of patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma at major centers in Australia. Eligible patients for this study analysis were aged 10 years and above, diagnosed with EFS between January 2010 and September 2020, and had completed first-line treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/ or surgery) by September 2020. All eligible patients were treated at an Australian specialty sarcoma center (one pediatric, three adult centers). This study was approved by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee and supported by the Australian and New Zealand Sarcoma Association.

2.2 Data collection

Clinical characteristics, treatment modalities, and survival data were collected for all patients from the ACCORD database, and/or individual medical records review. Treatment information included the duration of chemotherapy cycle (14- or 21-day schedule), received total dose of individual drugs adjusted for body surface area (including dose-escalation), and reasons for dose reduction, treatment delay, or discontinuation. A typical VDC/IE regimen comprised seven cycles each of VDC and IE: vincristine 1.5 mg/m2, doxorubicin 37.5 mg/m2 (2 days), cyclophosphamide 1200 mg/m2, alternating with ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2 (5 days), etoposide 100 mg/m2 (5 days) with pegfilgrastim support.22 A full course of doxorubicin was considered as 375 mg/m2 (usually five cycles) due to the risk of cardiac toxicity, and omission for the final two cycles of VDC was not recorded as a dose reduction if the cumulative maximum dose had been received.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics, and patterns of treatment, both for the entire cohort of EFS patients and the subgroup who received VDC/IE.

RDI was calculated using a previously described method, as the ratio of proportional dose () to proportional time delay (), .14 Proportional dose was equal to the received chemotherapy dose divided by the anticipated chemotherapy dose (100% of protocol), . Proportional time delay was equal to the number of days between the first and last day of treatment, divided by the planned time as per the published treatment schedule or clinical trial protocol (either 14 or 21 days), .22 For those who underwent surgery, there was an allowance for 18 days hematological recovery before surgery, and 14 days surgical recovery prior to resuming chemotherapy. A patient who received treatment without dose reduction or delay would have = 1, = 1, and RDI = 100%. Acceptable RDI of chemotherapy was defined as ≥85% based on previous studies in solid tumors demonstrating a statistically significant benefit above this threshold.23

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software Version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). PFS and OS for those receiving VDC/IE were described using the Kaplan−Meier method. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compare outcomes by RDI, age, gender, Ewing's type, primary site, and stage. Clinical predictors of achieving an acceptable RDI were explored using univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics

A total of 155 consecutive patients with histologically confirmed EFS were identified from ACCORD (n = 145, 94%) and pediatric medical records (n = 10, 6%) between 2010 and 2020. Nine patients were excluded due to incomplete baseline record (transfer of care to another center with no ongoing follow-up), leaving 146 patients eligible. Of the 146 patients, 135 (93%) received chemotherapy as part of primary treatment; VDC/IE (n = 104, 77%), VIDE with or without autologous stem cell transplantation (n = 30, 22%), and oral etoposide (n = 1). All patients over 60 years of age (n = 8) did not receive chemotherapy as primary treatment, and a further three patients received surgery with or without radiotherapy. Of 104 patients who received VDC/IE, 76 (73%) had complete chemotherapy data for RDI analysis, the remainder 28 (27%) were excluded due to insufficient records (n = 21), chemotherapy delivered at an external facility (n = 5), or previous treatment for non-EFS cancer (n = 2).

The baseline characteristics of all patients with EFS (146) and the subgroup who received VDC/IE and had complete record for RDI analysis (n = 76) were similar, as shown in Table 1. For the VDC/IE cohort, the majority were male (59%), with a median age of 25.4 years (range 10.3–59). The proportion with skeletal and extra-skeletal histology were 43% and 57%, respectively. Over half had localized disease at diagnosis (stage II, n = 28 [37%]; stage III, n = 21 [28%]).

| Characteristic | All patients with EFS, N = 146 n (%) | VDC/IE cohort, N = 76 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||

| Median (range, years) | 24.9 (10.3–81.8) | 25.4 (10.3–59.0) |

| 10–19 | 45 (31) | 18 (24) |

| 20–39 | 73 (50) | 44 (58) |

| 40–59 | 20 (14) | 14 (18) |

| ≥ 60 | 8 (6) | 0 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 61 (42) | 31 (41) |

| Male | 85 (58) | 45 (59) |

| Tumor type and primary site | ||

| Skeletal | 72 (49) | 33 (43) |

| Axial | 42 (58) | 19 (56) |

| Appendicular | 29 (42) | 15 (44) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Extra-skeletal | 73 (50) | 43 (57) |

| Head and neck | 3 (4) | 2 (5) |

| Thorax | 8 (11) | 6 (14) |

| Extremity | 24 (33) | 12 (29) |

| Abdomen/pelvis | 26 (36) | 13 (31) |

| Spine | 8 (11) | 8 (19) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Not specified | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Extremity | 1 | 0 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| Localized | 87 (60) | 49 (64) |

| Metastatic | 47 (32) | 21 (28) |

| Unknown | 12 (8) | 6 (8) |

| Treatment received | ||

| Surgery | 104 (71) | 56 (74) |

| Radiotherapy | 88 (60) | 50 (66) |

| Chemotherapy | 135 (93) | 76 (100) |

3.2 VDC/IE cohort: Chemotherapy completion rate, dose reductions, and interruptions

Of the 76 patients who received VDC/IE, 54 (71%) patients completed scheduled chemotherapy without dose reduction. VDC/IE was delivered on a 14-day cycle in 24 patients (32%) and a 21-day cycle in 49 patients (65%), with three patients (4%) switching from a 14- to 21-day cycle. Fifteen patients (20%) at one site underwent chemotherapy dose-escalation from a starting dose of 100% of protocol due to good tolerance, as part of institutional guidelines, with 10 of these 15 (67%) having doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide dose escalated (range 110%–130% of protocol dose) and 14 (93%) dose escalated ifosfamide and etoposide (range 110%–120%).

Table 2 shows number of instances of dose reduction, cycle delay or omission, and treatment cessation, by age group. Twenty (26%) had a cumulative dose reduction of 1%–20%, two (3%) required a dose reduction by 21%–50%, and none required a dose reduction greater than 50%. For those whose chemotherapy was dose-escalated, they were only considered to have a dose reduction if their cumulative dose fell below 100% of the original anticipated dose.

| Characteristic | 10–19 years N = 18 n (%) | 20–39 years N = 44 n (%) | 40–59 years N = 14 n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete scheduled chemotherapy without dose reduction | 12 (67) | 34 (77) | 8 (57) | 54 (71) |

| Dose reduction | ||||

| Dose reduction | 6 (33) | 10 (23) | 6 (43) | 22 (29) |

| Cycle delay | ||||

| Cycle delay > 7 days | 13 (72) | 28 (64) | 8 (57) | 49 (64) |

| > 14 days from surgery to chemo | 5/13 (39) | 9/28 (32) | 1/8 (13) | 15 (20) |

| Mean delay surgery to chemo (range, days) | 24.4 (19–32) | 27.4 (19–45) | 46 (–) | 27.7 (19–46) |

| Cycle omission | ||||

| Cycle omitted | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (14) | 3 (4) |

| Mean cycles omitted per pt (range, n) | – | 1 (–) | 2.5 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Ceased treatment | ||||

| Due to toxicity | 2 (11) | 7 (16) | 4 (29) | 13 (17) |

| Disease progression | 0 | 5 (11) | 1 (7) | 6 (8) |

| Median cycle stopped at (range, n) | 9.5 (6–13) | 9.5 (2–13) | 10 (7–13) | 9.4 (2–13) |

There were 43 instances of drug dose reduction in 22 patients (29%). The most frequently reduced agent was doxorubicin (49% of cycles), followed by cyclophosphamide (35%), ifosfamide (35%), etoposide (33%), and vincristine (23%). Doxorubicin was more commonly reduced in the 40- 59-year-age group (43%), compared to 20–39 years (38%) and 10–19 years (19%). The reasons for dose reduction are detailed in Table 3. Myelosuppression was the most common reason for dose reduction, with at least 40% of total reductions due to febrile neutropenia.

| Reason for chemotherapy dose reductiona | 10–19 years, n (%) | 20–39 years, n (%) | 40–59 years, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 3 (34) | 3 (18) | 6 (35) | 12 (28) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 (34) | 5 (29) | 5 (29) | 13 (30) |

| Neutropeniab | 6 (67) | 6 (35) | 8 (47) | 20 (47) |

| Cardiac | 0 | 2 (12) | 1 (6) | 3 (7.0) |

| Gastrointestinal (including diarrhea, ileus, and mucositis) | 0 | 0 | 2 (12) | 2 (4.7) |

| Renal | 0 | 0 | 1 (6) | 1 (2.3) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 0 | 1 (6) | 3 (18) | 4 (9.3) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 2 (12) | 0 | 2 (4.7) |

| Unknown | 4 (22) | 3 (7) | 0 | 7 (16) |

- a Multiple reasons could be documented per instance of dose reduction.

- b At least 8/20 (40%) of total reductions for neutropenia due to febrile neutropenia.

There were 95 occasions of cycle delay greater than 7 days, among 49 patients (65%). The most common reason for delay was myelosuppression (neutropenia in 36%, thrombocytopenia in 31%, and anemia in 21%). Other documented reasons included patient preference (10%), mental health problems (17%), other infection (39%), and unrelated surgery (17%).

Treatment was stopped early in 19 patients (25%), which included six patients (32%) with disease progression. Six patients were assessed as ceasing treatment due to toxicity (32%), three due to infection (16%), and two due to patient preference (11%). Two patient deaths occurred, both over 20 years of age, one due to disease progression and one unknown. Cycle omission was rare, with only eight cycles omitted among three patients due to neutropenia, nephrotoxicity, fatigue, and patient preference.

3.3 RDI and survival outcomes

Fifty-seven percent of patients achieved an acceptable RDI of ≥ 85% (67% aged 10–19, 61% aged 20–39, and 29% aged 40–59). Median RDI was 87% (98% aged 10–19, 89% aged 20–39, and 80% aged 40–59). Compared to those aged 10–19 years, the odds ratio of an acceptable RDI for patients aged 20–39 was 0.79 (95% CI 0.24−2.46, p = 0.70) and for patients aged 40–59 was 0.20 (95% CI 0.04−0.86, p = 0.04).

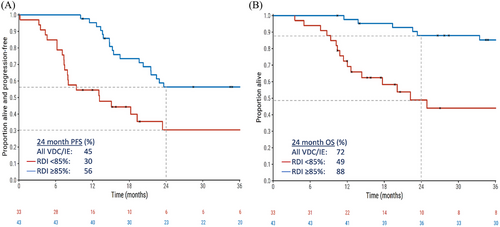

The median follow-up for patients receiving VDC/IE was 37.3 months. For all patients, the median PFS was 22.4 months (2-year PFS 45%) and the median OS was 113 months (2-year OS 72%). RDI ≥85% conferred a significantly higher PFS than RDI < 85% (2-year PFS 56% vs. 30%; adjusted HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.18−0.82; p = 0.01; Figure 1A). OS was also higher in patients achieving RDI ≥85% (2-year OS 88% vs. 49%; adjusted HR .25, 95% CI 0.10−0.63; p = 0.004; Figure 1B). Regarding the effect of age, PFS and OS varied according to age group in univariable analyses (log-rank p = 0.06 and 0.05, respectively), but not when limited to those who received RDI ≥85% (log-rank p = 0.9 and 0.6, respectively), thus confirming the prognostic importance of RDI.

RDI was a prognostic factor for OS in both univariable and multivariable models, after adjustment for age, gender, Ewing's subtype, primary site, and stage (Table 4). The only other prognostic factor for OS on multivariate analysis was stage at diagnosis, with metastatic disease conferring a statistically significant inferior outcome.

| Characteristic | Univariable analysis HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable analysis HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDI | ||||

| RDI < 85 | – | |||

| RDI ≥ 85 | 0.29 (0.14–0.61) | 0.001 | 0.25 (0.10–0.63) | 0.004 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 10–19 | – | – | ||

| 20–39 | 1.39 (0.53–3.64) | 0.51 | 1.83 (0.60–5.60) | 0.29 |

| 40–59 | 3.18 (1.12–9.02) | 0.03 | 2.28 (0.66–7.93) | 0.19 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | – | – | ||

| Male | 1.92 (0.87–4.51) | 0.10 | 2.35 (0.84–6.57) | 0.10 |

| Tumor origin | ||||

| Skeletal | – | – | ||

| Extraskeletal | 1.05 (0.50–2.20) | 0.91 | 0.32 (0.10–1.05) | 0.06 |

| Primary site | ||||

| Extremity | – | – | ||

| Nonextremity | 0.75 (0.35–1.62) | 0.46 | 1.12 (0.42–2.94) | 0.83 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Stage II | – | – | ||

| Stage III | 1.98 (.68–5.75) | 0.21 | 5.40 (1.10–26.49) | 0.04 |

| Stage IV | 4.30 (1.62–11.41) | 0.003 | 5.21 (1.44–18.78) | 0.01 |

4 DISCUSSION

We have reported the outcomes for Australian patients with EFS receiving VDC/IE chemotherapy over a 10-year period from 2010 to 2020. Over two-thirds (71%) completed their scheduled chemotherapy without dose reduction and 57% achieved an acceptable RDI. The PFS and OS at 2 years for those who achieved acceptable RDI compared to those who did not achieve acceptable RDI were 56% versus 30% (p = 0.001) and 88% versus 49% (p < 0.001), respectively. The odds of completing scheduled chemotherapy and achieving an acceptable RDI were better for those aged 10–19, compared to those aged 40–59. For the 20–39 years age group, there was a trend to receiving a less acceptable RDI but this was not statistically significant.

Prior to the publication of the practice-changing Euro-Ewings 2012 trial in 2020, a variety of different chemotherapy regimens have been used in the first-line treatment of EFS, and institutional practices can be variable.4, 8, 15, 21, 24, 25 This is reflected in our Australian dataset with most (77%) patients treated with VDC/IE, of which a third had compressed 14-day cycles, and six patients were treated on a pediatric trial protocol where the number of cycles ranged up to 17. Other treatment approaches in EFS no longer in practice were also observed in our cohort, including high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell support in three patients based on Euro-Ewing99/Ewing 2008 trial,26 and dose-escalated chemotherapy based on the Intergroup Study (IESS-II), in 15 patients.27 These patients were not included in this study analysis.

In our study, we found that survival outcomes in EFS were contingent on achieving an acceptable RDI, with those receiving an acceptable RDI ≥85% having a clinically and statistically significant improvement in PFS and OS at 2 years compared to those with RDI < 85%. There has been considerable debate regarding the impact of age on survival outcomes. A retrospective review of 383 patients with EFS by Karski et al. reported inferior 2-year OS in those aged > 40 years. However, the greater proportion of axial primaries, extra-skeletal histology, and later stage at diagnosis for those aged > 40 years might also explain the differences in survival compared to those < 40 years.28 The overall equal distribution of skeletal and extra-skeletal EFS in our cohort is unusual as skeletal EFS usually has a higher incidence; however, this may relate to the older age of our cohort.29 In our patient groups, when broken down by age, the incidence of skeletal EFS decreased with age (61% age 10–19, 46% age 20–39, and 14% age > 40), which is consistent with previous reports.4, 28 Extra-skeletal histology has invariably been reported as a poor prognostic factor in EFS.2, 28 For our patient population, after adjustment for age, gender, Ewing's subtype, primary site, and stage, RDI remained an independent prognostic factor for OS.

Patients 40 years and older were significantly less likely to achieve an acceptable RDI compared to their younger counterparts. In a study of 81 patients, Zhang et al. found that completion of at least 12 cycles of VDC/IE with fewer instances of cycle delay were the strongest positive prognostic factors for survival, while Gupta et al. reported poorer outcomes in adults with an average 10 cycles VDC/IE completed.19, 21 It is, therefore, more plausible that inferior outcomes observed in older adults with EFS could be as a result of failing to achieve an acceptable RDI. There are few studies in the sarcoma literature that look directly at this question. Among younger patients < 35 years, Delepine et al. found the only significant predictors of OS to be RDI and histological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for EFS.11 In a cohort of 45 patients with rhabdomyosarcoma treated with VAC, Kojima et al. reported lower RDI in adults compared to children predominantly due to hematological toxicity, infection, and peripheral neuropathy, although this was not associated with any survival difference, likely due to the small study.13 Expanding to all solid tumor types, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 studies in the nonadjuvant-setting reported a positive relationship between acceptable RDI and OS, using a threshold of ≥80% and ≥85% RDI.23

Maintaining RDI is contingent on chemotherapy tolerance and management of toxicity, which is often a challenge in clinical practice. We observed that adults > 40 years had higher rates of dose reduction and were more likely to have cycles omitted or treatment ceased earlier due to toxicity. Conversely, while those < 40 years had more instances of cycle delay, dose reduction was less frequent. This suggests a more aggressive approach to maintaining RDI in younger patients. Overall treatment delays were recorded in 64% of patients, which was far higher than the 18% reported by Bacci et al. in patients aged > 40.4 Across all age groups, hematological toxicity was the dominant reason for dose reduction, although rates were highest in < 40 years. This is comparable to the literature, with myelosuppression frequently reported as the most common side effect, with hematological toxicity rates of up to 100% (all grades).4, 5, 19, 21

Our study is strengthened by the use of a comprehensive and prospectively maintained database to capture real-world clinicopathologic and treatment data for a large cohort of Australian patients with EFS. The ability to record chemotherapy information including dose and cycle timing allowed us to calculate RDI, which sets this study apart from other retrospective reviews. Our study represented the largest dataset for EFS in Australia and highlighted the necessity for a central database to guide research for sarcoma. One limitation of our study was that collection of toxicity data was restricted to details documented in the medical record, which seldom listed CTCAE grading. Therefore, the incidence of nonhematological toxicities may have been underestimated.

In summary, we found that survival outcomes in EFS are contingent on achieving an acceptable RDI of VDC/IE, which is especially challenging to maintain in adults aged over 40 years. A higher rate of dose reduction, cycle delay, and treatment discontinuation was observed in older adults, predominantly due to treatment toxicity, resulting in significantly inferior survival outcomes. How we can better accommodate for age differences, and whether age is a limiting factor due to biology of disease, biology of aging, or cumulation of comorbidities, remains uncertain due to a lack of clinical trial data for this specific patient population. The ongoing recruitment of adults with EFS to clinical trials including rEECur, an international randomized control trial of patients aged > 2 years with recurrent or primary refractory EFS,30 is essential to ensure outcomes can be reliably extrapolated to this population. The present study highlights the need for prospective collection of chemotherapy dose and intensity variables in addition to toxicity data, so that the optimal clinical strategies to overcome these barriers can be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Jasmine Mar, Janina Chapman, and all participants who contributed to the ACCORD national sarcoma database.

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee and supported by the Australian and New Zealand Sarcoma Association (ANZSA).