Gender diversity and leadership in Radiation Oncology in Australia and New Zealand

G Hesselberg: MBBS (Hons), RANZCR; M James MBBS (Hons), BSc, RANZCR; S Turner MBBS, PhD, FRANZCR; N Gupta MA, BA (Hons); P Mackenzie FRANZCR.

Abstract

Introduction

There has been a groundswell of discussion and activism surrounding gender diversity. Given the growing importance of this issue, a working group was established under the Faculty of Radiation Oncology (FRO) of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists' (RANZCR) Economics and Workforce Committee (EWC) to review the current status of gender diversity within radiation oncology (RO) in Australia and New Zealand.

Methods

De-identified data were provided from two recent FRO workforce censuses conducted in 2014 and 2018 with permission from the EWC. Further data were provided via direct correspondence with staff at the RANZCR and the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG), the major RO research group in Australasia. The data were collated in February 2021.

Results

Our results showed that compared to females, male radiation oncologists were more likely to be engaged in full-time active clinical work, hold a postgraduate degree and obtain a consultant or fellowship position following graduation. Male fellows were more likely to have leadership positions within RANZCR and TROG and self-identify as holding any leadership position. The 2018 census revealed that within the trainee cohort, there was almost an equal number of male and female trainees as well as an equal number of male and female trainees holding a postgraduate degree.

Conclusion

This review is an important first exploration into gender diversity across Australia and New Zealand's RO workforce. Whilst our study indicates that gender disparities exist, there are some indications that this may be equalizing out over time.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a groundswell of activism surrounding gender diversity in our society at large and more specifically, within the workplace. In Australia, there is ongoing disparity between men and women within the workforce as evidenced across multiple metrics.1 For example, the workforce participation rate remains significantly lower for women at 62.1% compared to men for whom it is 70.4%.1 In regards to women in leadership positions, the statistics within a corporate setting demonstrate a concerning discrepancy with only 18.3% of all CEO positions being held by women and 30.2% of boards and governing bodies having no female directors.1 Of relevance to the healthcare sector, there is a 15.7% gender pay gap despite this being one of the most heavily female dominant industries.2 Within Radiation Oncology (RO) specifically, the average taxable income for female Radiation Oncologists is half that of men.3

Gender workplace diversity refers to the equitable representation of people of different genders. This is seemingly on course to being achieved within the medical workforce – the 2020 Medical Deans Student Statistics report confirmed that females comprised 51% of all commencing medical students.4 However, this trend falls away within the actual practicing medical practitioner workforce with the latest 2020–2021 Medical Board of Australia Registrant data report demonstrating that females only make up 44.4% of the practicing cohort compared to 55.6% of their male colleagues.5

Achieving gender diversity is only one barrier to overcome when addressing workplace inequities within medicine. Aiming for gender equity within our society, and by extension our medical workforce, is of paramount importance. Gender equity, which is distinctly different from gender equality or diversity, refers to the “fairness of treatment for women and men, according to their respective needs and interests. This may include equal treatment or treatment that is different but which is considered equivalent in terms of rights, benefits, obligations and opportunities”.6

Given the growing importance of this issue, a working group was established under the Faculty of Radiation Oncology (FRO) of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists' (RANZCR) Economics and Workforce Committee (EWC) with the aim of reviewing the current status of gender diversity including gender representation in leadership positions within radiation oncology (RO) in Australia and New Zealand.

Methods

With permission from the EWC, de-identified data were provided from the two recent FRO workforce censuses conducted in 2014 and 2018.7, 8 Both censuses sought information from all active radiation oncologists and RO trainees within the Faculty and were conducted between July and September in the respective years. Many of the census questions were replicated across both studies allowing the analysis of workforce changes across the four-year period.

Further data specific to named leadership positions were provided via direct correspondence with support staff at the RANZCR and the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG), the major RO research group in Australasia. The data were collated in February 2021.

Data were interrogated to understand the current and previous gender landscape within the speciality as well as to analyse any potential changes between the census years. Most results are presented as simple percentages. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were produced for categorical and scaled variables. P-values for relevant variables were calculated and P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant. Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel and P-values were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. The use of the data for this project was approved by the FRO Economics and Workforce Committee and TROG according to the RANZCR and board processes and in accordance with the terms required for management of the survey data.

Results

Basic demographics

In 2014, there were 523 members on the RANZCR membership database, 381 Fellows and 142 RO trainees. In 2018, there were 617 members: 480 fellows and 137 trainees. The breakdown by gender and response to the censuses is outlined in Table 1.

| 2014 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total numbers (%) | Responded to survey (%) | Total numbers (%) | Responded to survey (%) | |

| Fellows | 381 | 298 (78) | 480 | 333 (70) |

| Male | 231 (61) | 178 (77) | 286 (60) | 193 (67) |

| Female | 150 (39) | 120 (80) | 194 (40) | 140 (72) |

| Trainees | 142 | 112 (79) | 137 | 106 (77) |

| Male | 79 (56) | 66 (83) | 67 (49) | 52 (78) |

| Female | 63 (44) | 46 (73) | 70 (51) | 54 (77) |

| Totals | 523 | 410 (77) | 617 | 439 (73) |

| Male | 310 (59) | 244 (79) | 353 (57) | 245 (70) |

| Female | 213 (41) | 166 (78) | 264 (43) | 194 (73) |

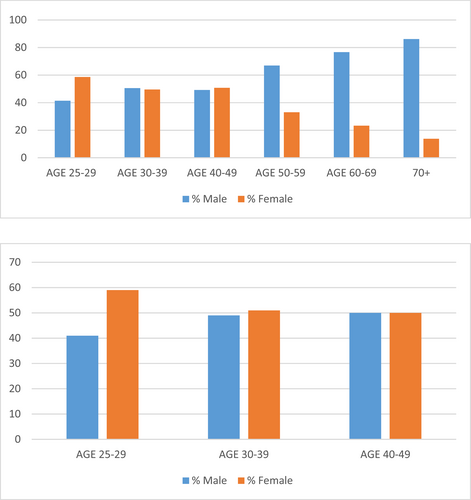

Workplace practice

In 2018, more male radiation oncologists were engaged in active clinical work compared to females – 174 (58.8%) versus 122 (41.2%) (P = 0.003). This discrepancy was even more apparent in 2014 with 165 (61.5%) of males in clinical work compared to 103 (38.5%) of females (P < 0.001). This represents a statistically significant change with decreasing P-value across the two census years. Of the ten respondents who were on leave in 2018, 9 of them were female. When reviewing the membership cohort in 2018, stratified by age, there were decreasing numbers of female ROs with increased age whereas there were trainee cohorts demonstrated more gender parity (Fig. 1a, b).

In 2018, there were overall more males working as RO consultants compared to females – 145 (58.9%) versus 101 (41.1%) in Australia and 26 (60.5%) versus 17 (39.5%) in New Zealand (P < 0.001). This was evident in the 2014 census where the majority of respondents working as RO consultants were male (62% male vs. 38% female) (P < 0.001). Conversely, women were more likely to work in locum positions with 4 of the 7 (57.1%) respondents answering this question being female.

Male respondents were more likely than female respondents to work in more than one practice in 2014 (P = 0.001); however, this was less evident in 2018 (P = 0.024). Male radiation oncologists were more likely to work in a combination of public and private work compared to females as reported in both the 2014 (P = 0.007) and 2018 (P = 0.015) censuses (Table 2).

| 2014 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male N (%) | Female N (%) | Male N (%) | Female N (%) | |

| Number of Practices: 1 | 45 (50.6) | 44 (49.4) | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) |

| Number of Practices: 2 | 67(62.0) | 41 (38.0) | 61 (50.4) | 60 (49.6) |

| Number of Practices: 3 | 38 (69.1) | 17 (30.9) | 48 (73.8) | 17 (26.2) |

| Number of Practices: 4 | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) |

| Private only | 22 (57.9) | 16 (42.1) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (51.7) |

| Public only | 80 (61.1) | 51 (38.9) | 79 (56.0) | 62 (44.0) |

| Public/Private | 64 (64) | 36 (36) | 70 (61.4) | 44 (38.6) |

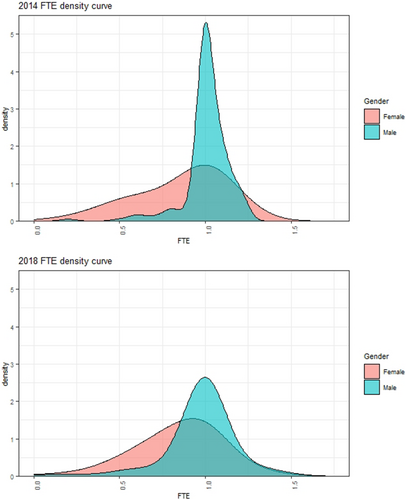

Female fellows were more likely to work less than 1.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) compared to males as revealed in both the 2014 and 2018 census (P < 0.001). The 2018 census results demonstrated that males worked significantly higher actual work hours per week – an average of 45.5 h versus 38.3 h and also spent more hours per week on new cases compared to females (7.1 h vs. 6.1 h). On average, males self-reported seeing more new patients per year compared to females (268 vs. 208 new patients in 2014, 269 vs. 210 in 2018).

In regards to FTE preference among trainees, both the 2014 and 2018 census demonstrated that the majority of respondents who wished to work full time for the first 10 years of their careers were male (75.6% male vs. 23.5% female in 2018, 79.2% male vs. 20.8% female in 2014). The results also showed that the majority of respondents who wished to work part time were female (23.9% male vs. 76.1% female in 2018, 32.7% male vs. 67.3% female in 2014). Parental leave and family commitments were predominantly identified by trainees as the reasons for wishing to work less than full time in their early careers. Between the 2014 and 2018 census, there was an increase in the number of females working part time as demonstrated by density plots in Figure 2.

Additional postgraduate qualifications

The 2018 census revealed that male fellows were more likely to hold a postgraduate degree than females. This question was not as comprehensively addressed in the 2014 census, so we were unable to draw a direct comparison between the two census data sets (Table 3). Within the trainee cohort, there appeared to be a more equal balance of the number of male and female trainees who held an additional degree in 2018 compared to 2014 (Table 4).

| 2014 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male N (%) | Female N (%) | Male N (%) | Female N (%) | |

| Research Higher Degree | 46 (76.7) | 14 (23.3) | 52 (70.3) | 22 (29.7) |

| PHD/MD | 24 (75) | 8 (25) | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.2) |

| Masters Degree | 22 (78.6) | 6 (21.4) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) |

| Other Higher Research Degree | Not asked | Not asked | 19 (65.5) | 10 (34.5) |

| 2014 | 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male N (%) | % Female N (%) | Male N (%) | Female N (%) | |

| Trainees with any postgraduate degree | 31 (60.8) | 20 (39.2) | 24 (50.0) | 24 (50.0) |

Career pathway postattaining RANZCR fellowship

In both censuses, male respondents identified as being more likely to obtain a consultant or fellowship position, whereas female respondents were more likely to obtain locum roles. In 2018, 64% of males versus 36% of female moved directly into a consultancy role as opposed to 44.4% of males versus 55.6% of females who reported working as locums. In 2014, only female respondents (five in total) identified as being unemployed following obtaining their fellowship. There were 4 males and 2 females unemployed in 2018.

Leadership positions

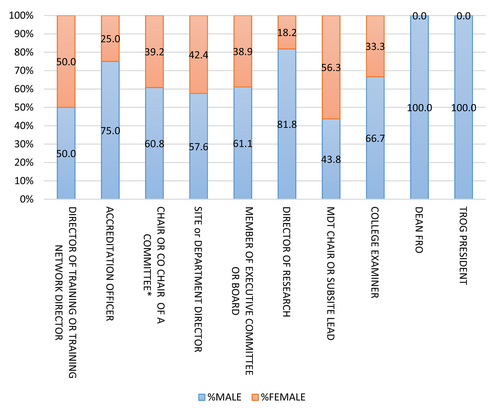

Self-identified leadership positions

The 2018 survey asked respondents to self-identify any currently held leadership positions. The survey question provided some examples of such positions. Over half of the respondents identified as currently holding one or more leadership positions (56.1%). The number of males in self-identified leadership positions exceeded the number of females, 60.3% versus 39.4%. Figure 3 demonstrates the gender breakdown of the self-identified leadership positions among respondents. Note that this leadership question was not asked in the 2014 census.

RANZCR FRO college leadership positions

The following results were obtained from data provided directly by RANZCR FRO and reflect the gender distribution among leadership positions as of February 2021. We defined a ‘leadership position’ within RANZCR as the following: a member sitting on one of the eight primary FRO committees; the chair of each FRO committee (each of whom is a member of the FRO Council), the FRO Dean who chairs the FRO Council and the Editor in Chief of RANZCR's Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology (JMIRO).

The current FRO Council is comprised of 17 members in total – 11 (64.7%) are male and 6 (35.3%) are female. Over the past 16 years, there have been 8 deans in total - 6 of the deans have been male fellows. Of the past five Chief Censors, two have been females. There are eight FRO committees comprised of 73 fellows who are active members. Of the committee members, 53% are male (39 of 73) and 47% are female (34 of 73). Of the 8 chairperson positions for each individual committee, 7 are held by male members with the only female chair being the chair for the Radiation Oncology Trainee Committee.

The college's records demonstrate that there is a slight male dominance in the current gender distribution of Directors of Training (DOT) with 44 of the 76 DOTs being male (57.9%).

RANZCR's Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology (JMIRO) has 15 RO members on the JMIRO editorial board which includes 1 male Editor in Chief, 1 female Deputy Editor and 13 Associate Editors – the majority9 of whom are female. The editor in chief position since 2007 has been held by 2 male ROs.

RANZCR college grants, awards and prizes

There have been a total of 254 college grants, awards and research prizes that have been awarded to fellows since 2010. The gender distribution of male and female fellows receiving these awards is 55.9% and 44.1%, respectively.

TROG leadership positions

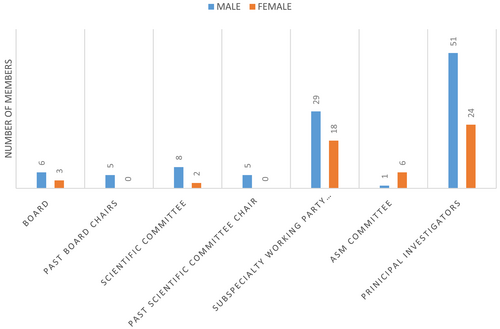

The following results were obtained from data provided directly by TROG and reflect the gender distribution among currently held leadership positions as of February 2021. We defined a ‘leadership position’ within TROG as the following: a member sitting on one of the Scientific Committees; the chair of each Scientific Committee, the Chair of the board, members of the board, current and past TROG trial principal investigators and the Chair and members of the TROG ASM Committee. The summary of this data is depicted in Figure 4.

Discussion

This is the first in depth review exploring gender diversity within the specialty of RO in Australia and New Zealand.

Workforce

The data indicates that there is an evident male dominance across a number of measured workforce parameters. There are however some encouraging differences between the 2014 and 2018 survey results showing a potential shift towards gender equality. For example, a more evenly balanced ratio of male to female fellows emerged from the 2014 to the 2018 census and similarly, the trainee male to female membership ratio almost reaches equivalence in 2018. This is highlighted where the data is grouped according to age: a significant male dominance is seen within older age brackets, however there is close to equal gender representation among the 30–39 and 40–49-year old cohorts. A similar shift, albeit not as strong, has been identified overseas such as in the Canadian Association of Radiation Oncology workforce report in 2017 which demonstrated a rise in female radiation oncologists from 18% to 38% and female trainee numbers reaching parity at 50%.10 In contrast to this, the 2017 workforce report by American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) demonstrated that women comprised only 28.9% of all radiation oncologist and that the male: female ratio was more than or equal to 2:1 across all age brackets.9 This disparity was noted despite there being over 50% female representation among North American medical school graduates.9

Both censuses identified that male fellows were more likely to obtain a consultant position following election to Fellowship, while females were more likely to work in locum positions. Furthermore, the respondents who identified a period of unemployment postfellowship attainment were exclusively female, however the reasons for this unemployment were not accounted for. The specific reasons for this were not explored in either survey but may be multifactorial in nature relating to holding a capacity to work full time, research higher degree status, family/childcare commitments and/or potential employer or systemic biases.

Workload

Male radiation oncologists are more likely to work 1.0 FTE and higher actual work hours compared to their female colleagues. Furthermore, male radiation oncologists see more new patients per year. Interestingly, when this data set was specifically analysed for the New Zealand workforce, it was noted that while female radiation oncologists worked less than 1.0 FTE, they saw a similar number of new patients per year (n = 229.8) compared to their male colleagues (n = 240.4).11 Neither survey explored the reasons why male radiation oncologists were more likely to work in a combination of public and private work compared to females. Potential contributing reasons for this may include a disparity in employment opportunities, financial incentives or more attractive leave and remuneration structures between public and private workplaces.

Higher education and academic endeavours

Male fellows were more like to hold research higher degrees than females. Since 2007, both editors in chief for JMIRO have been male, however the majority of associate editors were female. The data from TROG indicated that 68% of current or past clinical trial principal investigators have been male. Gender disparities within the RO academia sphere have been universally identified. For example, an analysis of a U.S. academic RO faculty found that females had significantly fewer publications and were less likely to obtain full professorship or hold chairperson positions.12 This is not unique to RO – in academic medicine women are less likely to be full professors even after accounting for age, experience and research productivity measures.13 Our data did not explore formal university appointments or affiliations among fellows to understand if similar disparities exist in Australia and New Zealand. Among trainees, there does, however, appear to be a trend towards an equal number of male and female trainees who hold a higher degree.

Leadership

Our review highlighted a distinct gender gap existing within our specialty's leadership positions. The census data indicated that there was a higher proportion of males who self-identified in leadership positions compared to females and this was confirmed by the data supplied by the FRO and TROG. Faculty Council members, current and past deans and college committee chairs are dominated by male fellows and this is similarly the case for the TROG board members, board Chairs, Scientific Committee members and Chairs and Sub-specialty Working Party members.

This issue is not unique to Australia and New Zealand. In the past 60 years, there have only been 4 female presidents of the ASTRO.12 Within U.S. RO academic programs, only 20% had a female program director and only 12% had a female chair.14 Of the 725 invited speakers for the ASTRO annual meeting between 2012 and 2016, only 27% of these were women.15 More broadly, across U.S. medical oncology, RO and surgical oncology academic programs, women composed of only 21.7%, 11.7% and 3.8% of chair positions, respectively.16 Within the medical education leadership sphere, there exists on authorship gender disparity with males authoring 69% of global oncology curricula.17

Future change

It is imperative to understand that despite the number of female trainee numbers reaching parity with their male counterparts, thus mitigating a ‘pipeline’ issue for fair gender representation, a number of barriers remain to achieving gender equality and equity in our specialty across all metrics. While direct and overt discrimination against women within our specialty and medicine is subsiding, unconscious bias still contributes to the glass ceiling.18, 19 Research in both the medical and corporate spheres have identified a number of strategies to mitigate unfair representation. Initiatives proposed include targeted mentorship of females by both male and female mentors, workplace training programs and educational modules to reduce gender bias and promoting female leadership representation at all levels.18-20 Many such initiatives have been adopted and/or developed within RANZCR FRO.

On a broader societal level, shifting social expectations surrounding caregiving activities, providing funding support for childcare, having equitable parental leave policies and promoting flexibility within the workplace are all essential initiatives.18-20 Ultimately, equal and diverse representation within our workforce and leadership will ensure that we are providing our patients and society with the most talented, qualified and inclusive cohort of radiation oncologists in Australia and New Zealand.

Study limitations

There are a number of limitations for this study. Firstly, the two census surveys were not designed to specifically interrogate gender differences within the surveyed workforce. While there were questions specific to leadership roles, this was not the primary focus of the census and the 2014 census did not include this subset of data. Furthermore, many of the RANZCR and/or TROG leadership position terms are for 2–3 years and it is possible that an individual's leadership role was not captured between the two census dates. We acknowledge the bias with self-reporting and in particular, the inherent gender bias that may result in under-reporting of leadership positions by females due to influences such as the impostor phenomenon (IP). This is a psychological concept where by “high-achieving individuals attribute their successes to external factors and are unable to internalize success”.21 Studies have shown that females are significantly more likely to report impostor beliefs than men.21 An attempt was made to analyse any difference between the two data sets collected between 2014 and 2018. However, we acknowledge that the census questions and style was not identical between these two years and any differences evident may be incidental findings rather than an emerging trend.

While our review captured some quantitative measures of gender inequity in our speciality, it does not delve into more subjective assessments of gender inequity. Research into this space has highlighted the challenges faced by women in RO - both as the result of unconscious bias or overt discrimination or harassment.22 One study by Jones et al.22 identified five common issues: gaining respect and exercising authority, obtaining resources and financial compensation, entering and advancing along the career pipeline, grappling with double standards and transcending internalized discrimination. Additionally, we did not tease out the various contributing factors to this inequity such as income discrepancy between public and private work, remuneration arrangements, social factors such as caring and family responsibilities or societal/governmental factors such as parental leave policies.3 Finally, our review does not include any data on race, ethnic diversity or members who identify with non-binary gender roles. We were therefore unable to explore whether any disparities exist for these cohorts.

In conclusion, this review is an important first exploration into gender diversity across Australia and New Zealand's RO workforce. Whilst our study indicates that gender disparities exist, there are some indications that this may be equalizing out over time.

Acknowledgements

Sara Hughes: Policy Officer Policy and Advocacy Unit; The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. Susan Goode: Chief Executive Officer; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley - University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.