‘Through education, we can make change’: A design thinking approach to entry-level dietetics education regarding eating disorders

Open access publishing facilitated by Griffith University, as part of the Wiley - Griffith University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Abstract

Aims

To co-create strategies and identify opportunities to integrate eating disorder content within dietetics curricula at one Australian university with stakeholders using a design thinking approach.

Methods

A pragmatic mixed-methods, participatory design approach was used. An online survey explored the learning needs of dietetic students and recent graduates regarding eating disorders. Following the survey, a one-day design thinking retreat was held with stakeholders who were identified from the research team's professional networks. Eating disorder dietitians, learning experts, dietetic students, graduates, and those with lived experience were asked to identify strategies to enhance students' confidence and competence to provide care for people living with eating disorders. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and qualitative data were analysed using inductive coding and reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

Sixty-four students (n = 55, 86%) and recent graduates (n = 9, 14%) completed the online survey (26% response). Seventeen stakeholders attended the retreat. Four themes were identified: (1) changing perceptions of eating disorder care from specialist to ‘core business’; (2) desiring and advocating for a national change to dietetics curricula; (3) importance of lived experience at the centre of curriculum design and delivery; and (4) collaborating to co-design and deliver eating disorder content at university.

Conclusion

Raising awareness, upskilling students and educators, enhanced collaboration between universities and stakeholders, and the inclusion of lived experience were key to preparing students to provide care to people seeking support for eating disorders. Further research is needed to assess the impact these strategies have on dietetic students' confidence and competence.

1 INTRODUCTION

Dietitians have an essential role in the nutritional management of eating disorders1 and often identify disordered eating behaviours in individuals.2, 3 However, many dietitians report lacking confidence to provide care to people experiencing eating disorders and express a desire for more training.4-6 Similarly, medical and mental health professionals also report a lack of confidence to treat eating disorders.7 Inadequate training, inexperience, and limited exposure to eating disorders can lead to low confidence, reluctance to provide care, reduced empathy, and negative attitudes towards people with eating disorders among health professionals.7, 8 The rising incidence of eating disorders has increased the likelihood of dietitians providing care to people with eating disorders across all healthcare settings.9 Due to the complexity of eating disorders, dietitians wanting to specialise are encouraged to seek further professional development and supervision to ensure safe and effective practice.1, 10 However, entry-level dietitians often provide care to people with eating disorders with little prior experience or education.11 Investigating innovative ways to upskill the dietetic workforce may assist dietitians to feel confident and competent to provide safe and timely nutrition care.

Nutrition and dietetics programs delivered at universities are required to meet the minimum standards to attain accreditation from professional and regulating bodies.12, 13 These standards ensure all graduates are competent to provide safe and effective nutrition care in a variety of settings. In addition to the accreditation standards, regulatory bodies also require dietitians to meet professional standards and competencies to support practice.14-16 As highlighted by the National Competency Standards for Dietitians in Australia14 elements 1.2, 2.2, 4.2, and 4.3, basic eating disorder care could be considered a core competency. Currently, basic eating disorder content is included within the dietetics program, focusing on communication strategies. More in-depth content on eating disorders is provided as optional learning for students. This is reflective of findings from Parker et al., 2023 who found eating disorder curricula across 19 accredited programs in Australia and New Zealand are mostly limited to a two-hour lecture at an introductory level.17 Student views are often sought to identify whether curriculum aligns with their perceived learning needs and preferences and to identify any gaps. Online surveys to assess students' perceptions of sustainability,18 semi-structured interviews to explore students' experiences of a research training intervention,19 and focus groups to explore students' construction of competence20 and their experiences with placement models21 have all been used to inform curriculum design.

The potential personal impact of educating student dietitians in eating disorders is important to acknowledge. Nutrition and dietetic students are a high-risk population for disordered eating behaviours and eating disorders.22 A systematic scoping review included 19 studies exploring the global prevalence of eating disorders within dietetic students found a high prevalence of body image and weight dissatisfaction, orthorexia nervosa tendencies and up to 32% of students were at high risk of eating disorders.22 These findings suggest the integration of eating disorder content within dietetics curricula warrants additional consideration to minimise potential harm. Recently, Bennett et al. explored nutrition students' and academics' experiences of a co-created curricula intervention regarding disordered eating, eating disorders, and body image.23 Students found the content and reflecting on their own relationships with food and body empowering and it helped them to feel less alone in their personal experiences and more connected to the profession.23 Additionally, the National Eating Disorders Strategy 2023–2033 recommends eating disorder content be embedded in all health professional tertiary education as an important step in future workforce development.24 Thus, the inclusion of eating disorder-specific content within dietetics curricula is crucial for a confident and competent workforce. Exploring this content within curricula seemingly has a positive impact on students individually, however, understanding how curricula content may support development of skills and knowledge related to eating disorders in the emerging dietetic workforce warrants further investigation.

Design thinking is a human-centred, participatory design approach used to engage participants in the research more deeply when compared to other approaches such as focus groups, interviews, and surveys.25, 26 This research approach engages a range of stakeholders and challenges them to design innovative solutions that are beneficial for the end user.27 In recent years, this creative problem-solving approach has been used in Canada to redesign continuing professional development for medical physicians,28 and in the United States to design the curriculum for an interdisciplinary design thinking graduate course.29 Design thinking is a highly collaborative process that focuses on building empathy towards end users and includes diverse perspectives to generate new insights to address complex problems.30 Research shows that expert views do not always align to views provided by those affected by a given problem (end users).31 A participatory design approach has been shown to improve engagement, retention, and satisfaction with programs.32, 33 Therefore, the aims of the current study were to explore dietetic students' perceived learning needs and to co-create educational solutions with stakeholders to integrate eating disorder content within dietetics curricula at one university.

2 METHODS

This study used a mixed-method pragmatic design. Pragmatism is an action-oriented paradigm that focuses on addressing ‘real world’ problems and is well suited to participatory design research.34 This paradigm prioritises the most practical methods to address the research question and acknowledges the important link between individuals' lived experiences and knowledge generation.34, 35 The research project came from a desire to enhance the confidence and competence of the dietetic workforce regarding eating disorders and for stakeholders to contribute to optimising care in this space. A pragmatic approach strongly aligned with the values of the research team, and the principles of design thinking and provided flexibility to explore what was meaningful to end users. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Griffith University Research Ethics Committee (ref: 2022/408).

First, an online survey was conducted to understand the expressed learning needs and preferences of dietetic students and recent graduates from one university (see supplementary material). The survey was informed by literature.36 Two researchers external to the project with experience in dietetic education and who were familiar with the university program pilot tested the survey. The feedback received was incorporated into the final survey which included 13 items. Students' stage of degree, preferred mode of learning, and time investment were explored through closed-ended questions. Open-ended items explored perceptions of eating disorders, previous professional development activities, and knowledge and skills related to eating disorders perceived as important to learn while at university.

Recruitment for the online survey occurred via email. Students currently enrolled in a Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics at Griffith University and those who had graduated within the previous 12 months (N = 250) were invited to participate in the online survey. An information sheet, and consent form were included in the email, along with a link to the survey. Participation was voluntary and survey completion implied consent. Survey participants could elect to enter a draw to win 1 of 4 $50 (Australian dollars) eGift vouchers. The survey remained open for 2 weeks. Quantitative data from the online survey were analysed using descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel. Qualitative data from open survey responses were analysed using Braun and Clarke's reflexive thematic analysis approach, described in detail below.37

Following the online survey, a one-day design thinking retreat was held with diverse stakeholders to identify innovative ways to include eating disorder content within dietetics curricula. A combination of purposive and convenience sampling was used to identify and recruit a variety of stakeholders with relevant experience and expertise from the research team's professional networks. As the retreat was in person, participants were limited to those in the local vicinity. Identified stakeholders with extensive experience in learning and teaching, eating disorder dietetic care, and lived experience of eating disorders were emailed individually. The research team were also approached by a leading eating disorder advocate who was subsequently invited to join the one-day workshop. Students who had completed all course work (honours students and those completing placement within the local area) and so were familiar with the current program were invited via email to register their interest in attending the retreat. The email included an information sheet, details of the retreat, and a link to an online expression of interest form for those interested in participating. The online form collected basic demographic information to assess eligibility and obtain any dietary requirements. Stakeholders were asked to select the perspective they felt most comfortable sharing throughout the design thinking process. For example, if someone was a dietitian with lived experience, they could choose to share from a dietitian or from a lived experience perspective. Three potential participants extended the invitation to colleagues they felt would be interested. The research team aimed to recruit up to 25 design-thinking participants to have a maximum of five small groups on the day and ensure adequate time for all participants to contribute.

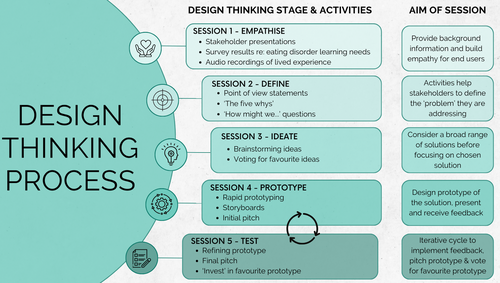

The design thinking retreat followed the Stanford d.school five-stage method including: (1) empathise, (2) define, (3) ideate, (4) prototype, and (5) test.38 Figure 1 provides an overview of the design thinking process and activities used at the retreat. The retreat was held in person, at the university campus. Authors attended the retreat as facilitators (two authors) or as a participant (one author). The research team was all females and included three dietitians, one of whom is a doctoral candidate exploring dietetic care for eating disorders (AH), and two have extensive experience as dietetic educators and researchers as well as working as clinicians (LJM and LB). SRT is a social marketing researcher, educator, and practitioner with extensive experience using participatory design approaches and facilitating educational workshops.

At the beginning of the retreat, participants were allocated to table groups to ensure maximum role diversity within each design team. Design thinking is based on shared power and emphasises the importance of all perspectives being considered equally valuable.30 However, it was acknowledged that some power imbalances may exist between stakeholders such as clinicians, dietetic educators, and students for example. To mitigate potential imbalances, students were not seated at a table with a dietetic educator. To overcome other potential power imbalances, activities were structured to ensure all participants provided input individually at each step of the design process prior to any team discussions.

During the empathise stage of the retreat (Stage 1), there were three key activities. First, a summary of the online survey results was shared at the retreat to set the scene and ensure students' and recent graduates' voices were at the centre of the design thinking process. Second, participants heard from professionals in the field regarding the eating disorder education needs of dietitians and what content is currently included in the dietetics program. Stakeholders then listened to audio recordings of lived experiences of seeking dietetic care for eating disorders to facilitate empathy building.

Stage 2 of the design thinking process focuses on problem definition. Using what they had learnt through the empathise stage, stakeholders engaged in a series of tasks including ‘point of view statements’ and ‘how might we’ questions to define the problem they were trying to address.27

Stage 3 was the ideate stage. This stage comprised of a brainstorming activity where stakeholders collectively generated ideas to integrate eating disorder content into dietetics curricula. The table groups then chose their favourite idea. In Stage 4 stakeholders spent time developing their prototype. In the final stage of testing (Stage 5), groups received feedback on their prototype. They then refined their prototype, making adjustments based on the feedback provided. Final prototypes were pitched to the group. Further methodological detail used for the design thinking retreat and the prototypes developed are reported separately. The current manuscript presents student survey results and the key themes produced from the design thinking process. Results are reported in line with the standards for reporting qualitative research39 and COREQ checklists.40

Qualitative data was collected at the retreat via worksheets, and design thinking activities, and verbal consent was obtained for photographs and video recordings on the day. Video recordings were taken of the initial and final pitch presentations which ranged from 2 to 11 min. The recordings were transcribed verbatim (otter.ai) and transcripts were checked for accuracy and modified as needed. Qualitative data from the design thinking activities were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.37 All qualitative data were entered into Microsoft Excel where line-by-line coding was conducted by the lead author until no new codes were identified. Codes were then reduced and refined by the lead author in collaboration with the research team through an iterative process of data immersion and reflection.37 Preliminary themes were identified from codes and final themes were produced through discussion, revision, and collaboration with the research team to enhance reflexivity and trustworthiness of the findings.41 Synthesised member checking provided design-thinking participants with the opportunity to provide feedback on analysed data and confirm whether the themes reflected the key ideas that emerged from the retreat.42 Ten stakeholders completed member checking and eight felt the identified themes aligned with their experience. Two stakeholders provided feedback regarding the interpretation of the first theme, which was incorporated into the final themes presented in this study. This collaborative approach enhanced the trustworthiness of the findings and ensured themes were reflective of what participants had shared at the retreat. Credibility of the findings was demonstrated through the use of verbatim quotes to substantiate the identified themes.43 A reflective journal was maintained by the lead author throughout the project, to reflect on background professional knowledge, beliefs, assumptions, and experiences as a dietitian and researcher and how this may influence the interpretation and analysis of data.

3 RESULTS

A total of 64 students and graduates completed the online survey (26% response rate). An overview of participants' stage of degree and previous eating disorder education is displayed in Table 1. There was a similar response from all stages of the Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics program, and most had not completed any eating disorder-specific education (87%).

| Item | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage of nutrition and dietetic degree | ||

| First year | 18 | (28) |

| Second year | 11 | (17) |

| Third year | 15 | (24) |

| Fourth year | 15 | (24) |

| Recent graduate | 9 | (14) |

| Have you completed any eating disorder-specific education | ||

| No, I have not | 56 | (87) |

| Yes, I have completed eating disorder-specific courses and education | 5 | (8) |

| Yes, I have learnt through my own lived experience | 3 | (5) |

For the online survey results, overall the survey participants perceived eating disorders to be an important topic to include in the Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics degree due to the prevalence within the community. Those within the first 3 years of their degree were motivated by flexible learning (n = 11), increasing knowledge about eating disorders (n = 10), and obtaining resources (n = 10). Whereas those who had completed all Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics coursework (Year 4 students and graduates), were more concerned with learning new skills they could use in practice (n = 14). Year 4 students and recent graduates felt unprepared to care for clients with eating disorders, and that there was not enough eating disorder content covered in the degree. Students also desired case studies and felt eating disorder content needed to be delivered sensitively as dietetic students may have living/ lived experience of eating disorders.

When asked what eating disorder knowledge and skills survey participants felt were important to learn at university, four learning priorities were identified. These included: (1) Psychological aspects of eating disorders, (2) basic knowledge regarding eating disorders (e.g., types, aetiology), (3) effective counselling and communication skills, and (4) nutrition care and strategies to treat eating disorders. Fourth-year students and graduates reported needing basic skills to provide basic treatment and were interested in learning about setting-specific treatment and screening tools. The preferred mode of learning and hours students wanted to invest learning about eating disorders are recorded in Table 2. There was a strong preference for an interactive workshop (n = 35), followed by an online module (n = 14), and most students would prefer to spend 3-<10 h on eating disorders throughout their degree. Three themes were produced from survey data including: (1) Understanding scope of practice, managing expectations and self-care; (2) Putting theory into practice to reflect the real world, and (3) Keeping content simple and focused on foundational knowledge and skills.

| Item | Years 1–3 (n = 44) | Year 4 and recent grads (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Preferred way to learn about eating disorders at university | ||

| Interactive workshop | 20 (45) | 15 (75) |

| Online module | 13 (30) | 1 (5) |

| Seminar | 7 (16) | 1 (5) |

| Simulation | 2 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Other | 3 (7) | 0 (0) |

| How much time would you prefer to invest in learning about eating disorders? | ||

| <1 h | 1 (2) | 2 (10) |

| 1–2 h | 4 (9) | 0 (0) |

| 3–<5 h | 13 (30) | 9 (45) |

| 5–<10 h | 11 (25) | 5 (25) |

| 10–<15 h | 7 (16) | 2 (10) |

| 15–<20 h | 4 (9) | 1 (5) |

| 20 h + | 4 (9) | 1 (5) |

For the design thinking retreat, twenty-one expressions of interest were received, and all were invited to attend. Two participants cancelled prior to the retreat due to personal reasons and a further two did not attend on the day. A total of 17 stakeholders participated in the retreat including six learning and teaching (non-dietetic) professionals, five eating disorder dietitians, three dietetic students, one recent graduate, one eating disorder advocate with lived experience, and one dietetic educator. Eating disorder dietitians had experience working in various settings including hospitals, inpatient, outpatient, community, and primary care settings. Some had extensive experience in the supervision and education of dietitians regarding eating disorders. Four key themes were produced from the qualitative data obtained from the design thinking activities and are presented with indicative quotes in Table 3.

| Theme | Description | Indicative quote/text |

|---|---|---|

|

Participants felt eating disorders should not be assumed to be a specialist area. Rather, all dietitians should possess foundational knowledge and skills to provide care for people seeking support for eating disorders | “We agree that dietitians are expected to be the experts in eating behaviour… then why is this not currently addressed in the dietetics curriculum?” (Group 2, initial pitch) |

| Increasing awareness and reducing stigma of eating disorders among students | “Yarning [or dialogue] circles where students can discuss in a safe place their experiences with eating disorders personally and their relationship with food.” (Group 1, prototype) | |

| Need for dietitians to feel comfortable to provide care for eating disorders and recognise when to refer on to appropriately skilled clinicians | “We need to have more dietitians comfortable in this space with knowledge of what's normal and abnormal eating behaviours, so that they're there to provide care to people with eating disorders in the community.” (Group 2, feedback session) | |

|

Participants felt eating disorder content should be included in all dietetic programs in Australia | “…include eating disorder content as a compulsory core competency, this is the only way to enact change and make it our core business.” (Group 4, initial pitch) |

| Including eating disorder content early within existing curriculum and upskilling educators to feel confident to deliver content | “Embed disordered eating and eating disorders into our curriculum, upskill lecturers and encourage to embed in curriculum from year 1.” (Group 2, initial pitch) | |

| “Upskill academics to be confident to include/ teach eating disorders and disordered eating behaviour content.” (Group 4, brainstorming) | ||

|

Learning from those with lived experience to enhance dietetic care | “One thing that we really took away from those consumers and carers that we listened to was around that relationship and that trust the person felt with the dietitian.” (Group 3, initial pitch) |

|

Subject matter experts, lived experience, learning experts and other health disciplines collaborating to design and deliver a holistic educational experience and increase student connection to professionals working in the eating disorder space | “We propose a consumer codesigned along with the multidisciplinary team eating disorder module for dietetic students. The hope is that we can run this with dietetic students first and then look at broadening to the wider interprofessional education opportunities as well.” (Group 3, final pitch) |

| “Facilitating networking events while students are at uni [sic] that introduce them to other eating disorder dietitians who work in the space.” (Group 2, brainstorming) |

Theme 1 was changing perceptions of eating disorder care from specialist to ‘core business’. Participants reported a need for an attitudinal change within the dietetics profession towards eating disorders. An illustrative quote in Table 3 described dietitians as eating behaviour experts and eating disorders should be seen as ‘core business’. Rather than assuming it to be a specialist area, stakeholders felt all dietitians should have foundational knowledge and skills regarding eating disorders and therefore it needs to be included in dietetics curriculum. In order to change perceptions within the profession, participants felt it was important to raise awareness and reduce stigma regarding eating disorders. One suggestion was to provide a platform for students to discuss their own lived experiences and relationships with food. Engaging in conversations through a facilitated ‘unpacking’ of personal experience, with a lived experience expert or by using anonymous discussion board posts were other suggestions.

Those with experience caring for people living with an eating disorder noted there are not currently enough dietitians who feel confident in this area to meet the increasing need for services. Including eating disorder content within dietetics, curricula was seen as necessary to help dietetic students feel more prepared and willing to provide this care in the future.

Theme 2 was desiring and advocating for a national change to dietetics curricula. To make a genuine positive change in the readiness of the dietetic profession to care for people living with an eating disorder, participants reported ‘you need to start at the top’. They felt strongly about advocating for a change that will see eating disorder content included in all dietetics programs in Australia. Working in collaboration with professional bodies was perceived as an opportunity to bring about a national, compulsory change to curricula.

Some felt it was important to consider the implications of introducing eating disorder content into the curriculum, such as what content it might displace and whether such changes would be embraced by educators. Shifting the focus from eating disorders to disordered eating, given the higher prevalence within the community was one recommendation. Participants noted it was also important to upskill educators who deliver the content to students as shown in Table 3. There was a perceived need to provide more learning opportunities for educators to enhance their knowledge and confidence to include and teach students about disordered eating and eating disorders.

Theme 3 was importance of lived experience at the centre of curriculum design and delivery. Learning from those with lived experience of eating disorders was perceived as important for dietetic students to build empathy and gain a deeper understanding of what helped people throughout their recovery. Listening to a lived experience educator, understanding preferred language, and codesigning a learning module were examples of how participants felt this could be included in dietetic education.

At the retreat, as an empathy-building activity, participants were invited to listen to audio recordings of consumers' and carers' experiences of dietetic care related to eating disorders. As a result, there was a strong focus on the need for dietetic students to develop effective communication and counselling skills, including how to develop trust and rapport (as shown in Table 3), how to navigate working with parents and carers, and focusing on progress rather than results.

Theme 4 was collaborating to co-design and deliver eating disorder content at university. Collaboration between universities, industry, eating disorder experts, and other health disciplines to co-design and integrate eating disorder content in curricula was valued by participants. Input from a variety of stakeholders would strengthen the content and provide a more holistic educational experience. Interprofessional learning experiences such as a workshop with psychology and dietetic students regarding disordered eating were suggested to assist students' learning and understanding of their roles and scope of practice. There was also a desire for more opportunities for students to connect with eating disorder clinicians to develop a deeper understanding of what is involved when working in this area. Table 4 presents a variety of practical strategies of how eating disorder content could be integrated into dietetics curricula that were identified by participants throughout the design thinking process.

| Content-based strategies | Collaboration-based strategies | Longer-term strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Including the disordered eating behaviours continuum into curriculum | Guest speakers such as eating disorder dietitians and those working in eating disorder organisations | Universities offering a bridging course in eating disorders for newly graduated dietitians |

| Building in disordered eating into case studies (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.) across all years of the program | Seminar delivered yearly for all cohorts, multiple universities | Include disordered eating behaviours in competencies for student dietitians |

| Eating disorder-specific sessions (different types and behaviours) | Run workshops for academics, facilitated by experts in the field | Dietitian tool kit for students, new graduates and later career dietitians regarding eating disorders |

| What not to do—helpful and unhelpful language and communication session | Listen to a lived experience educator—share with students what helped them throughout their eating disorder recovery | |

| Workshop (early stages of the degree) focusing on experience with food | Consumer-led workshops and education content | |

| Targeted placement experiences | Interprofessional team to develop materials to raise awareness and reduce stigma | |

| Run a workshop with psychology and dietetic students about treating disordered eating |

4 DISCUSSION

This study found that there is a strong desire to include eating disorder content within dietetics curricula and provides practical strategies identified by a range of stakeholders. Key actions to initiate this included changing perceptions within the profession, advocating for the inclusion of eating disorders in all accredited programs, and collaborating with lived experience and industry experts to design and deliver content. These findings can be beneficial for educators and those involved in curricula design.

Raising awareness of eating disorders was perceived as an important step in changing perceptions within the dietetics profession. Aligning with previous findings,22, 44 lived experience was evident among survey participants, and the need for sensitivity when presenting this content to dietetic students was expressed in their responses. Hughes and Desbrow found personal experience with eating disorders and obesity were primary motivators for seeking a career in dietetics for 30% of undergraduate dietetic students.44 Providing students with a platform to explore their own experiences with food and body was identified by participants to help raise awareness and reduce stigma among students. This is consistent with Mahn and Lordly's recommendation to provide students with a compassionate environment to explore concerns with food and body image.45 Acknowledging the likelihood of lived experience within dietetic students is imperative, albeit seldom done, as it has important implications for educators and future curricular design. Further research is needed to understand how this topic can be explored in a safe and ethical manner and evaluations are needed to understand the impact changes to curriculum have on students' professional identity and preparedness to provide care to people impacted by eating disorders.

Advocating for a change to accreditation to make eating disorders a core competency within all dietetics programs in Australia was a key focus of retreat participants. It is important to note that in Australia and New Zealand, accreditation12, 46 and national competency standards14, 15 are not specific to individual health conditions. Rather, the standards are designed to ensure curriculum is within an evidence-based paradigm and that students are exposed to integrated and holistic learning experiences that equip them with the knowledge and skills to address current and emerging health priorities in a variety of settings.12, 46 Standards of practice and professional performance specific to eating disorders are available in Australia and New Zealand10 and United States,1 however, these are targeted towards practising dietitians rather than students. Specific conditions covered within dietetics curricula are at the discretion of individual university programs. A limited understanding of contemporary curriculum requirements among design-thinking participants may be due to only one dietetic educator participating in the present study. A recent qualitative study by Parker et al. found course convenors had conflicting views regarding the inclusion of eating disorder content beyond an introductory level in dietetics curricula.17 Some participants perceived eating disorders as a specialty area to be pursued after graduation, while others recognised an increasing number of new graduates entering private practice and the likelihood of engaging with people at risk of or experiencing eating disorders.17 Rather than a sole focus on eating disorder-specific content or a stand-alone module, highlighting skills already being taught within curricula and relating this to the eating disorder context can be a way of scaffolding and integrating content within programs.

Participants felt it was important to upskill academics and educators regarding eating disorders to confidently present and discuss this content with students. They felt course content needed to be appropriate and sensitive to the needs of students, and for academics to feel supported in their role. This is consistent with Bennett and Dart's call for guidance on how educators can support and have open conversations regarding disordered eating and eating disorders with students.47 A recent study found academics had conflicting views regarding exploring disordered eating and eating disorders and body image within curricula. While some welcomed the opportunity, others reportedly lacked confidence or felt this was outside the scope of their role as an academic.23 As the inclusion of this content within tertiary programs has been identified as a priority for workforce development,24 more guidance and clarity is needed regarding academics' role and how they can deliver this content confidently and sensitively.47 Application of a participatory-design approach, such as design thinking, that includes the perspectives of certified eating disorder clinicians, lived experience educators and academics can design content that is evidence-based and targeted to the learning needs of students and future health professionals.23

The inclusion of lived experience of eating disorders to design and deliver content was a key element identified throughout the design thinking process. Even the simple practice of listening to recordings of consumers' and carers' lived experiences of dietetic care in this study was a powerful empathy-building tool for participants. Brand and colleagues offer new insights into integrating the lived experience voice into health professional education.48 The study describes the development of a co-produced workshop that offers an alternative way of understanding eating disorders with a recovery-oriented focus compared to the biomedical lens traditionally used in eating disorder education.48 Including lived experiences in education enables health professionals to develop a deeper understanding of people's experiences which are integral to therapeutic relationships and person-centred care.48 The current study offers a new approach to dietetic education with the inclusion of the lived experience voice which is not typically included in curriculum design. Exploring opportunities for collaboration between universities and eating disorder organisations to co-design or adapt existing resources that include lived experience may be an accessible way to incorporate content within tertiary education.

This study focused on one dietetics program in Australia. The learning needs identified in survey results were consistent with those identified in previous studies.9, 36 A key difference was the strong desire for an interactive workshop compared to online modules, and learning more about setting-specific treatment and screening tools. As the design thinking retreat was in person, participants were limited to those within the local vicinity. These findings are based on one dietetics program and may not represent other dietetic student cohorts. Despite this, the inclusion of a diverse range of stakeholders with a variety of experiences and expertise contributed to the overall findings and was a strength of the study.

In conclusion, the current study highlights key considerations identified by students and stakeholders regarding integrating eating disorder content within dietetics curricula. Raising awareness of eating disorders, upskilling students and academics, enhanced collaboration between universities and stakeholders, and the inclusion of lived experience were key to preparing students to provide care to clients living with eating disorders. As this is an emerging area of research, further exploration of how to integrate this content with minimal burden to educators is needed. Additionally, there is a need to assess the effectiveness of educational interventions for enhancing dietetic students' confidence and competence to provide care to people experiencing eating disorders.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AH completed this research in line with the requirements of her PhD, with supervisor involvement. AH, SRT, and LM contributed to the conception and design of the study. AH, SRT, and LM contributed to data collection. AH was primarily responsible for analysis and interpretation of the data and was supported by other authors. AH drafted the original manuscript, and LB, SRT, and LM critically reviewed and contributed to the manuscript. All authors are in agreement with the final manuscript submitted for publication and declare that the content has not been published elsewhere.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors declare AH was supported by a PhD scholarship awarded by Griffith University. LB's salary is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship (APP 1173496). No external funding was received for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

LB is a Company Director of Dietitians Australia. LJM is an Associate Editor of Nutrition & Dietetics. They were excluded from the peer review process and all decision-making regarding this article. This article has been managed throughout the peer review process by the Journal's Editor-in-Chief. The Journal operates a blinded peer review process and the peer reviewers for this article were unawre of the authors of the article. This process prevents authors who also hold an editorial role to influence the editorial decisions made. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was obtained from the Griffith University Research Ethics Committee (ref: 2022/408).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.