Communication and Psychosocial Functioning in Children With Tourette Syndrome: Parent-Reported Measures

Funding: This research was funded by the Social Science and Health Research Council of Canada.

ABSTRACT

Background

Previous studies indicate that a subset of children with Tourette syndrome (TS) experiences communication difficulties; however, the specific characteristics of these challenges remain underexplored.

Aims

This study aimed to (1) quantify the proportion of children with TS within a North American cohort exhibiting communication challenges as assessed by a standardized parent questionnaire, (2) determine how many children with parent-reported communication challenges had been diagnosed with a communication disorder, (3) examine the relationship between parent-reported co-occurring conditions and parent-reported communication skills, and (4) evaluate the association between parent-reported communication skills and parent-reported psychosocial functioning.

Methods and Procedures

Questionnaires were distributed to parents in North America through TS-focused social media groups and organizations (United States and Canada) and Canadian medical clinics specializing in TS care. Data collected included demographic information, information on tic severity and co-occurring conditions, parent-reported communication function using the Children's Communication Checklist, Second Edition (CCC–2), and psychosocial function using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

Results

The questionnaire was completed by 61 parents of children with TS. On the CCC–2, 62% of children obtained scores consistent with age-appropriate communication skills, while 38% obtained scores suggestive of communication challenges (> 1SD below the mean on general communication and/or social-pragmatic communication). Ten percent of children were reported to have a formal language disorder diagnosis. A significant correlation was observed between communication proficiency and psychosocial functioning: lower scores for general and social-pragmatic communication skills were associated with increased psychosocial difficulties (r = −0.44, p < 0.001). Notably, the presence of specific co-occurring conditions did not predict general communication or social-pragmatic communication challenges.

Conclusion and Implications

Speech-language pathologists (S-LPs) should anticipate that most children with TS will exhibit age-appropriate communication development; however, a substantial proportion will present with communication challenges in formal language and/or social communication. Medical practitioners are advised to promptly refer children for speech-language evaluation upon identifying potential communication challenges, particularly among those demonstrating heightened psychosocial difficulties. Comprehensive assessment by S-LPs should encompass both core language and social-communication dimensions.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

- There is evidence that communication challenges are relatively common in children with TS; however, we have little information about what these challenges look like and what other factors relate to them.

- This study demonstrated underdiagnosis of language and communication difficulties in TS, given the discrepancy between communication challenges suggested by CCC–2 results and the number of children who had previously received a communication diagnosis. Moreover, parent-reported challenges were observed for both social communication and general communication. This is the first study to report a correlation between psychosocial functioning and communication skills in children with TS.

- Children with TS should be referred for speech-language pathology services if challenges are indicated and attention should be placed on evaluating aspects of social-pragmatic language while promoting acceptance of social differences that are not interfering with functional communication.

1 Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by motor and vocal tics that appear during childhood (American Psychological Association 2013). Approximately 80% of people with TS have other co-occurring conditions, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and/or anxiety (Cath et al. 2022).

Language disorders have been found to occur at a rate of 12%–30% in children with TS (Claussen et al. 2018; Spencer et al. 1998; cf. 10% in the general population; Norbury et al. 2016). Past research highlights many strengths in language development for children with TS. Recent research has largely focused on language processing at the single-word level and has demonstrated strengths in verbal fluency and single-word vocabulary (see Feehan and Charest 2024). Certain elements of syntactic processing appear to be a strength as well, with children who have TS completing some grammatical tasks more quickly than typically developing peers while maintaining an equal level of accuracy (Walenski et al. 2007).

For those children with TS who do experience communication challenges (defined as challenges in language and/or social communication), there is little literature detailing where areas of need might be. There are a few very dated case studies suggesting that language formulation, coherence, and word-finding are areas of challenge (O'Quinn and Thompson 1980; Thompson et al. 1979). Further, a larger but similarly dated study suggests following directions may be a challenge (Hulbert 1986). Some studies suggest challenges with fluent expressive language formulation (De Nil et al. 2005; Donaher 2008). A more recent case study identified challenges in high-level language (i.e., inferencing and non-literal language comprehension) and narrative language (Legg et al. 2005).

Autistic characteristics and social communication skills have been measured in children with TS using the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (Ehlers et al. 1999), the Social Communication Questionnaire (Rutter et al. 2003), the Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino and Gruber 2012), and the first edition of the Children's Communication Checklist (Bishop 1989; Darrow et al. 2017; Eapen et al. 2019; Güler et al. 2015; Kadesjö and Gillberg 2000; Verté et al. 2005; Wadman et al. 2016). These studies have identified a high prevalence of autistic characteristics and/or challenges in social communication. Despite these findings and recent suggestions that social communication challenges could be a central component of TS (Albin 2018; Eddy 2021; Eddy and Cavanna 2013; Eddy et al. 2011), the nature of social communication concerns in children with TS is not well understood. Further, people who live with tics in our social world experience societal stigma and differences in their social experiences (Suh et al. 2022). The relationship between these factors and social communication differences in children with TS has not been explored.

Since co-occurring conditions are common among individuals with TS, it is important to consider how they contribute to language and social communication skills. Research addressing how co-occurring conditions contribute to language and social communication skills in children with TS is limited, and few studies have compared language skills in children with and without co-occurring conditions. Two studies reported that rates of language delays/disorders are high in children with co-occurring conditions (20-45%) and lower in children with ‘pure’ TS (3%–6%; Cravedi et al. 2018; Spencer et al. 1998). De Groot et al. (1997) found that children with ADHD and/or OCD performed more poorly than children with TS-only on a categorization test that measured concept formation (i.e., semantics). Similarly, Sukhodolsky et al. (2003) found that children with TS-only had similar expressive and receptive language skills as their peers, but children with co-occurring ADHD had significantly lower skills compared to peers. A few studies have reported that children with co-occurring ADHD performed similarly to children with TS-only on ‘social communication’ measures (which look at a broad range of social-pragmatic language skills) but received lower scores on ‘social interaction’ measures (which specifically measure skills and motivation for interactions in social situations; Carter et al. 2000; Darrow et al. 2017; Sukhodolsky et al. 2003). Pringsheim and Hammer (2013) found that a co-occurring diagnosis of ADHD contributed significantly to lower social communication scores in children with a range of tic disorders, including TS. Another study found that children with co-occurring OCD had stronger social communication scores compared to some of the other groups evaluated (i.e., TS-only and TS with ADHD; Darrow et al. 2017).

Psychosocial functioning considers aspects of both social and psychological function, and children with TS have been found to experience challenges in both areas (e.g., Gutierrez-Colina et al. 2015). Psychosocial challenges may relate to a wide range of factors, including co-occurring conditions (such as ADHD, OCD, and anxiety), severity of tics, school experiences, parenting styles and caregiver burden, motor skills, the complexities of living with tics in a socially-based world, and other socio-cultural factors (Robertson and Eapen 2017). The correlation between communication development and overall psychosocial skills in children with TS has not been investigated in previous research; however, research in other clinical groups has established an association between childhood communication disorders and later psychosocial challenges (e.g., Beitchman et al. 2001; Schoon et al. 2010; Wilmot et al. 2024).

In summary, there is some evidence that communication challenges are common in children with TS; however, we have little information about what these challenges look like and how they relate to other factors. This research aimed to investigate the extent to which a North American sample of children with TS experience communication challenges by parent report, to determine how many children have been diagnosed with a communication disorder, to understand how co-occurring conditions contribute to these skills, and to address the gap in our understanding of how these skills may relate to psychosocial skills. Communication skills were measured using the Children's Communication Checklist–2 (CCC–2; Bishop 2003), and psychosocial skills were measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997).

-

What proportion of children with TS demonstrate parent-reported challenges in General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication skills on the CCC–2?

Based on previous literature, we expected mean scores to approximate norms for speech, syntax, and semantics (Feehan and Charest 2024; Walenski et al. 2007). For all other domains of the CCC–2, we expected domain scores below norms since each domain is associated with coherence, high-level language, social communication, and/or autistic characteristics, all areas that past evidence indicates may be areas of challenge (Darrow et al. 2017; Eapen et al. 2019; Güler et al. 2015; Kadesjö and Gillberg 2000; Legg et al. 2005; Verté et al. 2005; Wadman et al. 2016).

-

What proportion of children with parent-reported challenges have an existing communication disorder diagnosis?

With no prior research to guide our hypothesis, we drew from the clinical experience of the first author, who practiced as a speech-language pathologist (S-LP) in a TS clinic, hypothesizing that a minority of children with parent-reported communication challenges would have received a communication disorder diagnosis.

-

How do co-occurring conditions predict General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication Composites in children with TS?

Based on previous literature, we expected that the presence of ADHD, OCD, and anxiety would be associated with lower scores on the General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication Composites (Carter et al. 2000; Cravedi et al. 2018; Darrow et al. 2017; de Groot et al. 1997; Spencer et al. 1998; Sukhodolsky et al. 2003).

-

What is the relationship between communication functioning and levels of parent-reported psychosocial functioning in children with TS?

There was no previous literature to guide our expectations; however, we expected a negative relationship between scores on the Communication Composites (General and Social-Pragmatic, where higher scores indicate better communicative functioning) and the SDQ difficulties score (where higher scores indicate greater difficulty) based on past literature in other clinical groups (e.g., Beitchman et al. 2001; Schoon et al. 2010; Wilmot et al. 2024).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Parent Questionnaire

All materials were created or modified for online delivery as a questionnaire via REDCap (Harris et al. 2009). The questionnaire materials consisted of four sections: background questions, the CCC–2 (Bishop 2003), the GTRS (Gadow and Paolicelli 1986), and the SDQ (Goodman 1997). This research was reviewed by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta, Pro00126653.

2.1.1 Background Information

The first section of the questionnaire presented a series of background questions developed collaboratively by three of the authors. These questions collected information about who diagnosed the child with TS, age at diagnosis, current age, sex, gender, country and region, co-occurring conditions, languages spoken in the home, parent education, and race/ethnicity.

2.1.2 Children's Communication Checklist–2 (CCC–2; Bishop 2003)

-

Speech: Articulation errors; intelligibility and fluency of speech.

-

Syntax: Sentence length and complexity; correct use of verbs, pronouns, and morphemes.

-

Semantics: Word choice and word retrieval.

-

Coherence: Ability to provide logical explanations/descriptions; use of clear referents; providing context; sequencing ideas.

-

Initiation: Consideration of audience and timing when deciding to talk to others; questions focused on detecting children who initiate at a higher frequency than what is typical.

-

Scripted Language: Use of memorized or overly precise intonation or word choice; echolalia; communication partner's enjoyment of the conversation.

-

Context: Adjustment of communication style to the needs of others; considering all information available when communicating comprehension of jokes, puns, and non-literal language.

-

Nonverbal Communication: Use and comprehension of facial expression and proxemics; use of gestures and eye contact.

-

Social Relations: Social anxiety, social responsiveness, and social acceptance.

-

Interests: Preference for unique/specific activities and conversation topics; rote communication style; preference for predictability.

Age-based norms are available for each domain (M = 10, SD = 3) and for the General Communication Composite (M = 100, SD = 15). The CCC–2 has demonstrated reliability and validity. Test-retest reliability coefficients range from 0.86 to 0.96, internal consistency coefficients range from 0.69 to 0.85, and all test items have demonstrated high interrater reliability (Bishop 2003). A cut-off score of 85 provides a sensitivity of 1.0 and a specificity of 0.85 for differentiating between children with language disorders and typical language development (Timler 2014). CCC–2 results correlate moderately with the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, Fourth Edition, a gold standard assessment (Semel et al. 2003; Kelso 2012). Eight of the ten subscales have been shown to differentiate children with ADHD (a similar clinical population to TS) from children without ADHD (Helland et al. 2014). The CCC–2 was selected as the communication measure because it has been used extensively in past research both for identifying childhood language disorders and for understanding social communication profiles in groups where social communication skills are of interest, such as autism, traumatic brain injury, ADHD, emotional-behavioural disorders, Williams syndrome, and anxiety (Bignell and Cain 2007; Fisher et al. 2022; Mackie and Law 2010; Philofsky et al. 2007; Towbin et al. 2005). The overall communication skills of participants were measured using the General Communication Composite of the CCC–2, which combines eight domains: Speech, Syntax, Semantics, Coherence, Initiation, Scripted Language, Context, and Nonverbal Communication. To measure social communication, we created a Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite following the work of Saul et al. (2022). This composite score represents the average of the Initiation, Context, and Nonverbal Communication domain scores (which are also included in the General Communication Composite). The composite is not normed in the CCC–2 test manual but has been used to measure social communication on the CCC–2 in past research (Saul et al. 2022). This composite aligns well with our intention to understand social communication because it captures social-pragmatic language skills (i.e., social communication skills) independently from form/content language skills (e.g., language structure and vocabulary).

2.1.3 Global Tic Rating Scale (GTRS; Gadow and Paolicelli 1986)

The third section of the survey collected information about the severity of TS using the GTRS. The wording of the GTRS was used verbatim, under an agreement for digital presentation (use agreement date: 21 November, 2022). It includes four severity questions rated on a four-point scale about how noticeable the child's tics are to others, how embarrassing they are for the child, how much they affect school and home functioning, and to what degree they cause social rejection (0–1 = low; 2 = medium; 3 = high). The GTRS is a 5-min measure that categorizes children into three groups based on the severity of their tic disorder. Experts in the field suggest this as an appropriate measure of tic disorder severity, but it has not been psychometrically evaluated (Martino et al. 2017). It was selected as a measure of tic disorder severity because it is a parent questionnaire (rather than a clinician-rated questionnaire) and because its brevity made it feasible to present along with the other lengthy questionnaires included in the survey. The measure was also selected for its ability to group children into three groups based on severity.

2.1.4 SDQ (Goodman 1997)

Section four collected information about psychosocial functioning using the SDQ. The wording of the SDQ was used verbatim, under an agreement for digital presentation (authorization invoice No. 101811). The SDQ is a measure for children 3–16 years of age. It yields a total score for psychosocial difficulties using items focused on emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems. Total scores are broken into four categories, where higher scores indicate more difficulty (0–13 = ‘close to average’; 14–16 = ‘slightly raised’; 17–19 = ‘high’; 20–40 = ‘very high’). The SDQ has demonstrated reliability and validity for evaluating psychosocial functioning. Borg et al. (2012) reported stable parent reports over 12 weeks and excellent internal consistency for the total difficulties score (Cronbach's Alpha = 0.83). SDQ results correlate moderately with a gold standard assessment (The Child Behaviour Checklist, Achenbach and Rescoral 2001; Achenbach et al. 2008). Sensitivity for predicting emotional-behavioural disorders was 0.83–0.98 (Goodman et al. 2004). The SDQ also has a good negative predictive value (93.6; Bourdon et al. 2005).

The functionality of the questionnaire presentation in REDCap was checked in two phases. The purpose of the functionality check was to ensure that background questions and standardized questionnaires were free of errors, were displaying correctly, and that respondents were able to navigate through the questionnaire with ease. The first phase involved sending the survey to four professionals with research and/or clinical training in communication sciences to seek feedback and corrections. The second phase involved sending the survey to three parents of children within the 8–16 years range who had communication and/or neurodevelopmental concerns to seek feedback and corrections. This feedback led to the introduction of numbers indicating how many pages were left in the survey. The updated survey represents the final version sent to participants.

2.2 Inclusion Criteria and Survey Dissemination

Parents of children with TS between the ages of 8–16 were recruited through social media, regional TS organizations across North America, and through local medical clinics that provide health services to people with TS. They were invited to complete the survey online. Potential participants were provided with a link and, upon clicking, were directed to an information letter and a statement of implied consent. Participants were able to access survey questions if they agreed to a copyright statement indicating that they would not copy the content of questionnaires and if their answers to the eligibility questions indicated that they fit the eligibility criteria (questions about age, diagnosis, and geographic location). Children with TS were included if they were between 8-16 years of age, located in North America and did not have a diagnosis of Autism or intellectual disability. An a priori sample size of 59 participants was calculated using Statcalc Version 4.0. The survey was started by 156 respondents. Of these, 64 submitted the survey (63 did not pass inclusion criteria and 28 did not complete all measures in the survey). Each submitted response was checked for completion. Three surveys we excluded due to missing responses, leaving 61 surveys. The survey was open from 2 November, 2022, to 9 November, 2023.

The children of the respondents were 41 males and 20 females; 58 children were cisgender, 2 were transgender, and one did not specify. Geographic location of respondents can be seen in Table 1. Children were 8–16.5 years of age (M = 12.5 years, SD = 2.2). Parents reported that children had been diagnosed with TS by their family doctor (n = 3), paediatrician (n = 10), psychiatrist (n = 18), neurologist (n = 25), or did not specify (n = 5). Age at diagnosis ranged from 3 to 14 years (M = 8.2 years). The racial/ethnic backgrounds reported by participants included Japanese (n = 1), Jewish (n = 1), White (n = 51), White/Filipino (n = 2), White/Black (n = 1), White/Indigenous (n = 1), White/Latin American (n = 1), White/South Asian (n = 1), and White/Southeast Asian (n = 1) (missing data n = 1). Primary languages spoken in the home included English (n = 57) and French (n = 4). Nine households reported being multilingual (Arabic, Bengali, French, Spanish, and Ukrainian). All parent respondents had completed high school and 56 (92%) had received college or university education. Canadian and United States participants were comparable on sex, age, and parental education. Tables 2 and 5 include participant geographic locations, co-occurring conditions, and tic disorder severity as determined by the GTRS. Thirty-one had low tic disorder severity (51%), 20 had a medium tic disorder severity (33%), and 10 had a high tic disorder severity (16%).

| Location (n = 61) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Canada | 43 (70) |

| Atlantic Canada | 4 (7) |

| Eastern Canada | 15 (25) |

| Western Canada | 19 (31) |

| Prairies | 5 (8) |

| United States | 18 (30) |

| Midwest | 3 (5) |

| Northeast | 10 (16) |

| Southeast | 1 (2) |

| Southwest | 2 (3) |

| West | 2 (3) |

| Score | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Communication Composite (Normative sample M = 100, SD = 15) | 60 | 117 | 89.8 (13.5) |

| Social-Pragmatic Composite (Normative sample M = 10, SD = 3) | 2 | 13 | 7.8 (2.4) |

| Domain subscale (Normative sample M = 10, SD = 3) | |||

| Speech | 1 | 12 | 9.1 (2.9) |

| Syntax | 4 | 12 | 9.7 (2.4) |

| Semantics | 2 | 13 | 8.3 (2.8) |

| Coherence | 3 | 13 | 8.0 (2.8) |

| Initiation | 1 | 15 | 7.6 (2.7) |

| Scripted Language | 3 | 13 | 8.1 (2.5) |

| Context | 2 | 13 | 8.3 (2.6) |

| Nonverbal Communication | 1 | 12 | 7.3 (2.9) |

| Social Relations | 1 | 12 | 6.6 (2.9) |

| Interests | 1 | 16 | 7.4 (3.5) |

- Note: Italicized domains are included in the General Communication Composite and bold italicized domains are included in the Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis

Scoring of the CCC–2 and SDQ were conducted according to the instructions as laid out in the published manual using paper forms and those norms were used to calculate domain and composite scores for the CCC–2. Totals from paper forms were transferred to an Excel spreadsheet along with REDCap data outputs. Data were checked for normality, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, outliers, and multicollinearity in SPSS. We used two regression models to test the contribution of co-occurring conditions to General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication Composites (research question 2). We used linear regression to determine if there was a significant negative relationship between each communication composite score and psychosocial functioning (research question 3).

3.2 Language and Social Communication Skills (Research Question 1)

Table 2 lists the ranges, means, and standard deviations for scores on composites and individual domains of the CCC–2. Sixty-nine percent of participants (n = 42) received a General Communication Composite score within one SD of the mean or higher (standard score of 85) and 31% (n = 19) received a score more than one SD below the mean. Sixty-six percent of participants (n = 40) received a Social-Pragmatic Communication score within one SD of the mean or higher and 34% (n = 21) received a score more than one SD below the mean. Sixty-two percent of participants (n = 38) received scores within one SD of the mean or higher for both composites, 28% (n = 17) received scores more than one SD below the mean for both composites, and the total number of children with low General Communication and/or Social-Pragmatic Communication scores was 23 (38%).

3.3 Communication Disorder Identification (Research Question 2)

The General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication scores for children with and without an existing communication disorder diagnosis are presented in Table 3. Numbers of participants with scores more than one SD below the mean for individual domains were as follows: Speech = 9 (15%), Syntax = 7 (11%), Semantics = 12 (20%), Coherence = 18 (30%), Initiation = 22 (36%), Scripted Language = 12 (20%), Context = 11 (18%), Nonverbal Communication = 19 (31%), Social Relations = 26 (43%), Interests = 23 (38%). Italicized domains are included in the General Communication Composite and bold italicized domains are included in the Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite.

| Scores < 2SD below mean | Scores 1SD–2SD below mean | Scores within the mean ± 1SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

Diagnosed with CD n (%) 6 (10) |

General Communication Composite | 4 (67) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) |

| Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 0 (0) | |

Not diagnosed with CD n (%) 55 (90) |

General Communication Composite | 2 (4) | 11 (20) | 42 (76) |

| Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite | 2 (4) | 13 (24) | 40 (73) |

- Abbreviation: CD—communication disorder.

3.4 The Contribution of Co-Occurring Conditions to General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication Skills (Research Question 3)

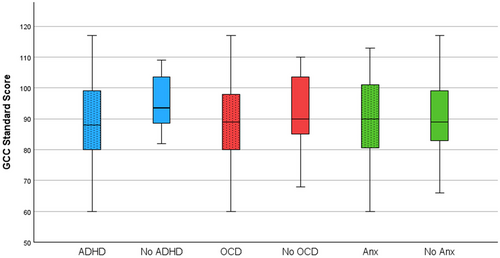

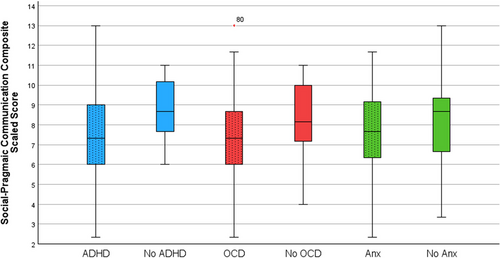

The numbers of participants with each co-occurring condition are presented in Table 4. Nearly all participants reported at least one co-occurring condition (n = 60, 98%) and 54 participants reported two or more co-occurring conditions (89%). Only one participant had no additional diagnosis (2%). The regression model testing ADHD, OCD, and anxiety as predictors of the General Communication Composite standard score was not significant F(3, 57) = 1.11, p = 0.23. The model explains only 2.4% of the variance in General Communication Composite scores (adjusted R2 = 0.024). None of the predictors accounted for a significant amount of unique variance. Similarly, the model testing ADHD, OCD, and anxiety as predictors of the Social-Pragmatic Communication score was not significant F(3, 57) = 2.11, p = 0.11. The model explains 5.3% of the variance of General Communication Composite Standard Score (adjusted R2 = 0.053). None of the predictors accounted for significant unique variance. Figures 1 and 2 present box and whisker plots for General Communication and Social-Pragmatic Communication scores for children with and without each diagnosis.

| Condition (confirmed or suspected) (n = 61) | n (%)a | Tic disorder severity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low n = 31 | Medium n = 20 | High n = 10 | ||

| Language/communication disorder | 7 (11) | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Speech disorder | 9 (15) | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Hearing loss | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ADHD | 45 (74) | 24 | 13 | 8 |

| OCD | 33 (54) | 15 | 9 | 9 |

| LD | 15 (25) | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Anxiety | 48 (79) | 24 | 15 | 9 |

| Depression | 16 (26) | 7 | 8 | 1 |

- Abbreviations: ADHD—attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; LD—learning disability; OCD—obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- a Totals > 100% because respondents could select more than one option.

3.5 Relationship Between Psychosocial Functioning and Communication Skills (Research Question 4)

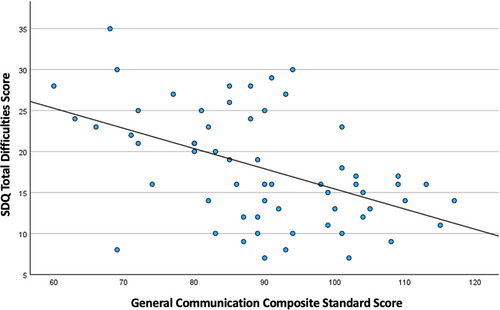

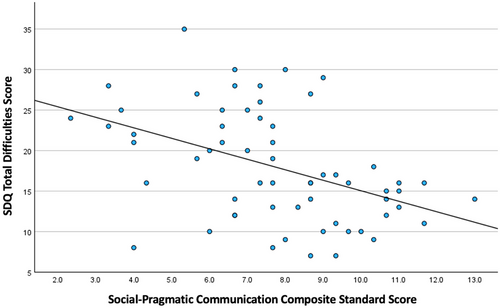

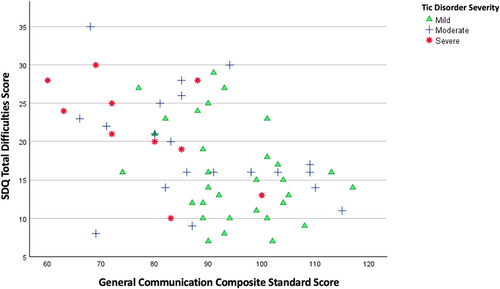

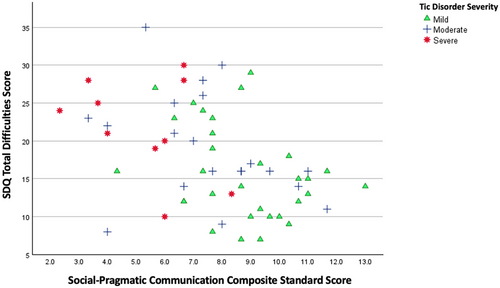

A total of 29 participants had parent-reported psychosocial difficulties in the ‘high’ or ‘very high’ range (48%) and 32 in the ‘average’ or ‘slightly raised’ range (52%). Among the 23 children with General Communication and/or Social-Pragmatic Communication scores more than 1 SD below the mean, 17 (74%) had high or very high psychosocial difficulties and six (26%) had average or slightly raised psychosocial difficulties. Among the 38 children with no communication concerns 12 (32%) had high or very high psychosocial difficulties and 26 (68%) had average or slightly raised psychosocial difficulties. Table 5 presents demographic information for children with and without psychosocial difficulties and with and without communication difficulties. There were significant medium-sized negative correlations between both composite scores and the SDQ total difficulties score (psychosocial skills). General Communication: r = −0.49, p < 0.001, one tailed and Social-Pragmatic Communication: r = −0.44, p < 0.001, one tailed. This means children with higher parent-reported communication skills had fewer parent-reported psychosocial difficulties and vice versa. Figures 3 and 4 present scatterplots demonstrating these relationships. Scatterplots of the relationship between psychosocial skills and communication skills for each tic disorder severity (low, medium, and high) can be seen in Figures 5 and 6. Children with high tic disorder severities cluster in the top left of the scatterplot with a combination of low communication skills and high psychosocial difficulties whereas children with low tic disorder severity cluster in the bottom right of the scatterplot with a combination of high communication skills and low psychosocial difficulties.

| Sex | Age (mean) | Parent education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Completed high school n (%) | College/ university n (%) | ||

| n = 41 | n = 20 | n = 5 | n = 56 | ||

| Psychosocial difficulties | |||||

| High or very high n = 29 | 20 (49) | 9 (45) | 13.0 | 2 (40) | 27 (48) |

| Average or slight n = 32 | 21 (51) | 11 (55) | 13.2 | 3 (60) | 29 (52) |

| General Communication Composite | |||||

| < 1SD n = 19 | 12 (29) | 7 (35) | 13.1 | 1 (20) | 18 (32) |

| ≥ 1SD n = 42 | 29 (71) | 13 (65) | 13.0 | 4 (80) | 38 (68) |

| Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite | |||||

| < 1SD n = 21 | 14 (34) | 7 (35) | 13.2 | 2 (40) | 19 (34) |

| ≥ 1SD n = 40 | 27 (66) | 13 (65) | 13.0 | 3 (60) | 37 (66) |

4 Discussion

This study sought to achieve four primary objectives: to examine the prevalence of communication challenges within a sample of children with TS based on parent-reported data, to identify the proportion of these children with formal communication disorder diagnoses, to determine the relationship between co-occurring conditions and communication skills, and to investigate the association between communication skills and psychosocial functioning.

4.1 Communication Skills

In past research with complex TS samples, 12%–30% of children were identified with language disorders (Cravedi et al. 2018; Spencer et al. 1998); however, no parent- or child-based assessments were conducted to confirm language disorder rates. We identified communication challenges in our sample through parent-report using a cut-off score of one SD below the mean (85) on the General Communication Composite of the CCC–2. This cut-off score has been previously shown to provide a positive predictive value of 83% for the identification of both Developmental Language Disorder (previously termed Specific Language Impairment) and Pragmatic Language Impairment (Bishop 2003). Based on this positive predictive power, we would expect approximately 16 of the 19 participants with low GCC scores to have a language disorder. However, only 6 had been diagnosed. This discrepancy between parent-reported communication challenges and communication disorder diagnoses highlights the need to address barriers to diagnosis such as limited awareness of language disorders among educators and healthcare providers. A low communication disorder identification rate is also concerning given that the children in our sample were well into their school-aged years: they could have accessed early intervention in their earlier years had they been identified. This also raises questions about how, for some children, unidentified and unaddressed language/communication challenges could be contributing to the broad range of family, academic, and social problems that are reported in children with TS (Ricketts et al. 2022). Communication challenges in early childhood relate to later problems in behavioural adjustment (Bornstein et al. 2013; Yew and O'Kearney 2013). Similarly, problems specific to social communication in early childhood have been connected to a range of later emotional and behavioural challenges (Dall et al. 2022). Early diagnosis and intervention are critical to mitigating the potential long-term consequences of unaddressed communication difficulties, such as academic underachievement, social isolation, and social-emotional problems.

Despite findings that indicate underdiagnosis, the majority of children in the sample demonstrated communication skills within the average range. Nonetheless, the substantial variability in individual scores underscores the heterogeneity of communication skills within our TS sample (domain scaled scores ranged from 1 to 16, M = 10, SD = 3). Ensuring that children experiencing challenges are referred to an S-LP for assessment and appropriate intervention is essential to supporting their communication development.

4.2 CCC–2 Domain Scores

The lowest domain scores in this sample were observed in Social Relations, Nonverbal Communication, Interests, and Initiation. These findings suggest that social-pragmatic communication difficulties may be particularly pronounced in children with TS, as Initiation and Nonverbal Communication make up two of the Social-Pragmatic Communication Composite domains. Vocal and motor tics may disrupt initiation and interrupt coordinated nonverbal communication, such as natural eye movements, facial expressions, and gestural cues (Eddy 2021). Additionally, tics could distract children with TS from recognizing their social partner's cues, resulting in missed communication opportunities. Direct observations of communication skills are needed to understand where differences in initiation and nonverbal communication lie and whether they go beyond tic-related differences in behaviour.

The Social Relations and Interests domains are often associated with autistic traits (Saul et al. 2022). Children with TS may experience social challenges arising uniquely from involuntary vocalizations/movements, socially inappropriate speech, or gestures during interactions. These difficulties can also interact with social challenges that arise from societal/self-stigma and social isolation (Robertson and Eapen 2017; Suh et al. 2022). Treatments that address tic-related symptoms, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, psychoeducation, and medication (Martino and Leckman 2022), may yield practical improvements in social relations for these children. Furthermore, interventions that promote TS awareness and acceptance through peer, parent, and teacher education have shown promise in fostering inclusive environments and improving social experiences (Chowdhury and Christie 2002; Fletcher et al. 2021; Ludlow et al. 2022; Mingbunjerdsuk and Zinner 2020; Nussey et al. 2014; Wu and McGuire 2018).

The lower observed Interests domain scores indicate that children with TS may exhibit preferences for specific activities or topics, a rote communication style, or a need for predictability. While these traits overlap with characteristics commonly seen in Autism, they have also been described in other neurodivergent groups, such as individuals with ADHD who are highly motivated by specific interests (Climie and Mastoras 2015) and individuals with OCD who value predictability (Williams et al. 2014). It is important to differentiate whether these traits represent functional impairments or are only notable because they deviate from neuronormative communication standards. Adopting a neurodiversity perspective may help reframe these characteristics as variations rather than deficits, encouraging a more inclusive understanding of communication differences.

4.3 Co-occurring Conditions

Although ADHD, OCD, and anxiety are frequently associated with communication challenges, this study did not identify significant relationships between co-occurring conditions and communication scores. While a few past studies have found that ADHD and/or OCD co-occurrence may relate to language challenges in TS (De Groot et al. 1997; Sukhodolsky et al. 2003), findings on social language have been inconsistent (Carter et al. 2000; Darrow et al. 2017; Pringsheim and Hammer 2013; Sukhodolsky et al. 2003). Overall, past research has found that children with TS who do not have co-occurring conditions also do not have elevated rates of language disorders (Cravedi et al. 2018; Spencer et al. 1998). Based on this, we expected that the presence of ADHD, OCD, and anxiety would contribute significantly to communication challenges; however, no additional diagnosis on its own and no combination of diagnoses was related to a higher likelihood of having communication challenges. These results reflect a sample that was composed almost entirely of children with multiple co-occurring conditions. This study's results highlight the complexity of isolating the impact of specific co-occurring conditions on communication skills in highly comorbid populations.

4.4 Psychosocial Skills in Relation to Communication

This study identified a clear association between communication challenges and psychosocial difficulties. While causality cannot be inferred, these findings suggest that interventions aimed at supporting communication development could yield positive psychosocial outcomes. The observed communication challenges, particularly in social-pragmatic domains, are likely to interact with academic performance, peer relationships, and emotional well-being. Future interventions should prioritize addressing these areas to enhance long-term functioning and quality of life.

4.5 Practical Implications for S-LPs

S-LPs can contribute to timely identification of language disorders in children with TS by advocating for and offering assessment services to children with TS. S-LPs can encourage appropriate referrals through educating parents, health professionals, and educators. They can provide information about typical language development, indicators of language disorder in children, and expected rates of co-occurrence of language disorders in children with TS.

S-LPs can support children with TS by implementing personalized, strengths-based interventions. Tailored therapy should address specific communication challenges, such as social communication difficulties, while embracing neurodiversity and recognizing each child's unique skills. Targeted strategies could include teaching children and their families’ compensatory techniques for managing tic-related disruptions in communication and providing education to teachers and peers to foster inclusive and supportive environments. Clinicians can expect to encounter children with psychosocial challenges and should be prepared with proactive strategies (Katsovich et al. 2003). Some general support strategies might include creating predictability using routines/schedules, minimizing noise and distractions, thoughtfully setting up the physical space, explaining goals and their importance, corrective and positive feedback, and positive regard (Gilkey-Hirn and Park 2012).

School-based programs focusing on peer understanding and stigma reduction about TS-related behaviours can further enhance communication outcomes (Chowdhury and Christie 2002; Fletcher et al. 2021; Ludlow et al. 2022; Mingbunjerdsuk and Zinner 2020; Nussey et al. 2014; Wu and McGuire 2018). Additionally, parent training and support groups are invaluable in helping families identify and address communication challenges early. Collaborative efforts between S-LPs, psychologists, educators, and health professionals are essential to ensure that interventions comprehensively address both communication and psychosocial needs, ultimately improving outcomes for children with TS.

4.6 Limitations

Several limitations related to our measures and our sample should be considered when interpreting these findings. Related to our measures, parent-report measures allowed us gain information about children's everyday communication and psychosocial functioning from individuals who know them well; however, it will be important in future research to incorporate the perspectives of individuals with TS and their healthcare providers, as well as direct observations of communication skills. Additionally, communication-focused assessments may capture differences attributable to tics rather than underlying communication difficulties. For example, facial tics can communicate non-verbal information that is incongruent with the message or context. This could lead to conclusions that overstate communication difficulties. Future research should explore how to differentiate tic-related communication interruptions from communication skill difficulties. The measures used in this study together created a lengthy questionnaire. This length may have contributed to the fact that 28 questionnaires were launched but not completed. We are not able to comment on the extent to which the findings would be similar or different had these questionnaires been completed. Finally, the GTRS was selected as a measure for its brevity in an already lengthy questionnaire; however, its psychometric properties have not been evaluated. Due to this, our findings regarding communication and psychosocial function as a function of tic disorder severity are considered preliminary. Future research investigating tic disorder severity in relation to communication factors should select robust measures to understand the interaction of these factors.

Related to our samples, the use of convenience sampling places limits on the generalizability of the findings. Our sample had a low number of United States households and a high number of children with co-occurring conditions. In our sample, 98% reported at least one condition and 89% reported two or more conditions. Previous literature suggests that about 80% of children with TS have co-occurring conditions and 50% have two or more conditions (Cath et al. 2022). Finally, an additional limitation was the lack of representativeness related to family characteristics. The education level of respondents was high, with over 90% having received a college/university education. This does not represent North American families as a whole, where approximately 69% of Canadians and 63% of Americans have a postsecondary degree or diploma (Statistics Canada 2016; United States Census Bureau 2022a). Similarly, the rate of multilingualism in our sample was low compared to Canadian (18%) and American (20%) rates (Statistics Canada 2023a; United States Census Bureau 2022b). A large proportion of families in our sample were White, making the number of racialized families low in comparison to Canadian (27%) and American (24%) rates (Statistics Canada 2023b; United States Census Bureau 2023).

4.7 Future Research Directions

To build on these findings, future research should directly assess the language skills of children with TS rather than relying solely on parent-reported measures. Observational studies could provide valuable insights into word-finding, coherence in language construction, and contextual communication skills. Understanding the lived experiences of individuals with TS through self-report is equally important. Additionally, future studies should critically evaluate communication characteristics to distinguish communication differences that present functional limitations from communication differences that present no functional limitations (i.e., that only deviate from neuronormative expectations). This will promote a strengths-based and neurodiversity-informed approach to intervention. Future research should recruit diverse samples that represent a representative range of educational levels and racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds.

The relationship between psychosocial functioning and communication warrants further investigation to determine whether improvements in communication skills contribute to enhanced psychosocial outcomes. Exploring the interplay between communication, co-occurring conditions, and tic disorder severity will also provide a more comprehensive understanding of these factors. Moreover, interdisciplinary collaboration among S-LPs, psychologists, and educators will be essential to develop interventions that address both the communication and psychosocial needs of children with TS. Finally, future research exploring how communication assessments perform in children with TS could use factor analysis to understand where items may identify tics.

5 Conclusion

This study highlights the need for increased awareness and proactive assessment for language disorders among children with TS, particularly during the early school years. Policy initiatives should prioritize integrating speech-language pathology services into multidisciplinary TS management teams. Personalized, strengths-based approaches to intervention should address pragmatic language challenges while respecting the neurodivergent identity of children with TS. School-based programs aimed at reducing stigma and increasing peer understanding of TS-related behaviours can foster more inclusive environments, while parent training and support groups could enhance early recognition and intervention for communication challenges. Addressing these needs holistically will contribute to improved outcomes and greater acceptance for individuals with TS.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Social Science and Health Research Council of Canada.

Ethics Statement

This research was reviewed by the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta, Pro00126653.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author A.F.