Evolving Decisions: Perspectives of Active and Athletic Individuals with Inherited Heart Disease Who Exercise Against Recommendations

Abstract

Individuals with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and long QT syndrome (LQTS) are advised to avoid certain forms of exercise to reduce their risk of sudden death. Cardiovascular genetic counselors facilitate both adaptation to, and decision-making about, these exercise recommendations. This study describes decision-making and experiences of active adults who exercise above physicians’ recommendations. Purposive sampling was used to select adults with HCM and LQTS who self-identified as exercising above recommendations. Semi-structured interviews explored participants’ decision-making and the psychological impact of exercise recommendations. Fifteen individuals were interviewed (HCM: 10; LQTS: 5; mean age: 40). Transcripts were coded and analyzed for underlying themes. Despite exercising above recommendations, nearly all participants made some modifications to their prior exercise regimen. Often these decisions changed over time, underscoring the importance of shared decision-making conversations beyond the initial evaluation. The importance of exercise was frequently cited as a reason for continued exercise, as were perceptions of sudden death risk as low, acceptable, or modifiable. Many participants reported that family and friends supported their exercise decisions, with a minority having family or friends that expressed significant reservations. Genetic counselors, cardiologists, and nurses can use these data to inform their counseling regarding exercise recommendations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and long QT syndrome (LQTS) are genetic cardiac diseases that confer an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (Hayashi et al. 2011; Maron et al. 2009). Sudden cardiac death has been associated with intense exercise in both conditions, leading to recommendations to avoid certain forms of exercise (Cheung et al. 2016). Expert consensus guidelines for sports activities in patients with HCM recommend avoidance of most competitive sports and high intensity recreational sports, including basketball, ice hockey, and body building (Gersh et al. 2011; Maron and Zipes 2015; Maron et al. 2005). Historically, guidelines for LQTS recommended avoidance of competitive sports, but recent American consensus guidance has allowed for the consideration of many such sports in well-treated individuals managed by a LQTS specialist (Ackerman et al. 2015). This change has sparked debate in the field, with European guidelines maintaining stricter restrictions, and some experts questioning the ethics of providers condoning possibly life-threatening activities (Mascia et al. 2018; Pelliccia 2014; Pelliccia et al. 2005).

Studies have shown that adhering to exercise recommendations causes emotional distress and affects social relationships (Asif et al. 2015; Berg et al. 2018; Luiten et al. 2016; Reineck et al. 2013). Two different studies found that approximately two thirds of individuals with HCM report a negative emotional impact from exercise restrictions (Luiten et al. 2016; Reineck et al. 2013). The challenges of exercise restrictions are thus a frequent topic of psychosocial counseling provided by cardiovascular genetic counselors (Caleshu et al. 2016; Ingles et al. 2011; Rhodes et al. 2016). In addition, there is a growing shift towards a shared decision-making approach to decisions about exercise in inherited cardiovascular disease (Ackerman 2015; Afshar and Bunch 2017; Baggish et al. 2017; Cheung et al. 2016; Etheridge et al. 2018; Law and Shannon 2012; Rizvi and Thompson 2002). Thus, there is an emerging role for cardiovascular genetic counselors to help patients make informed decisions about exercise, much as cancer genetic counselors help patients make decisions about prophylactic surgeries. However, there is a paucity of data available to inform this counseling. In particular, while prior studies have found that a significant number of individuals with HCM and LQTS (16–37%) continue to exercise contrary to recommendations (Johnson and Ackerman 2013; Reineck et al. 2013), very little is known about patients’ decisions to do so.

We aimed to examine the reasons why individuals choose to exercise above recommendations and the psychological and social consequences of the recommendations for those individuals. Insights gained from these data can guide how genetic counselors, nurses, and cardiologists communicate recommendations and contribute to the ongoing debate on the appropriate level of restriction.

2 METHODS

The majority of the study data was collected through qualitative semi-structured interviews and analyzed using thematic analysis (Hanson et al. 2011; Moustakas 1994). Data on demographic, athletic, and disease variables was collected by survey prior to interview. The study received institutional review board approval from Stanford University.

2.1 Participants

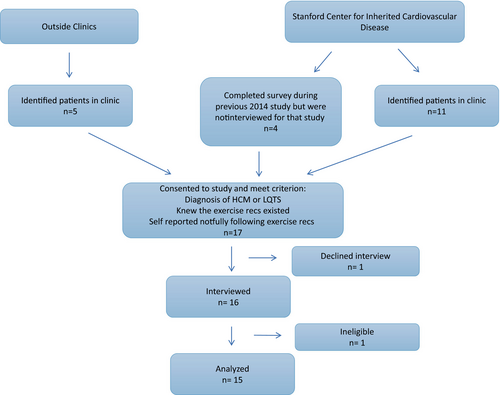

Prospective participants were identified through two approaches, both with the intent of identifying individuals with the lowest adherence to exercise recommendations. The first approach involving pulling the least adherent individuals (n = 4) from a pool of 54 individuals with inherited heart disease who participated in the survey portion of a mixed methods study previously conducted by our team (Luiten et al. 2016). The prior study focused on individuals who adhere to exercise recommendations and as such these four least adherent individuals were not interviewed as part of that study, though their survey data was included in our prior publication (Luiten et al. 2016). The second method of recruitment was through direct referral by clinicians at Stanford University (n = 8), University of Wisconsin-Madison (n = 1), and Indiana University (n = 2). These individuals were identified by clinicians as exercising beyond recommendations, and this was then confirmed via self-report. Patients referred directly through clinicians were briefly introduced to the study by their clinicians, and then were called by the first author (TS) for a more detailed discussion about the study.

All prospective participants were sent an email with consent documents and a link to take an online survey (discussed below) used for verifying eligibility and gathering of demographic and exercise data.

Interviewees were selected based on the following criteria: self-identified as not following exercise recommendations completely, reported two or more hours of weekly exercise, reported an exercise activity more vigorous than walking, were diagnosed with HCM or LQTS, were English speaking, and were 18 years or older. The inclusion criteria were developed with the intent of studying individuals who were most dramatically outside of exercise recommendations.

Twenty individuals were invited to participate, 17 responded and completed the survey. One of those 17 individuals declined the interview portion of the study, and the other 16 individuals were interviewed. One interview was excluded from further analysis because of complete adherence to exercise recommendations; thus, a total of 15 interviews and surveys were included in data presented here (Fig. 1).

2.2 Data Collection

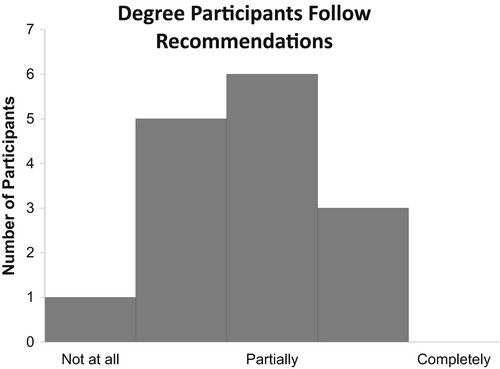

An online survey developed by our team in a previous study was used to select individuals for interview and to assess degree of adherence to recommendations, type and level of exercise activities, and basic demographic information (Luiten et al. 2016). Participants were asked to rate the degree they followed exercise recommendations on a Likert scale with anchors at 0 for “not at all,” 2 for “partially, ” and 4 for “completely.” The interview guide was designed to investigate the role of exercise in the participants’ lives, the participants’ decision-making over time, the psychological effect of recommendations on the participants, and the impact of recommendations on their social relationships. All participants completed a semi-structured interview with the same interviewer (TS). The interview guide was edited slightly after the first two interviews to add a specific question addressing the participants’ interactions with healthcare professionals regarding the recommendations. All interviews were conducted by phone and were digitally audiorecorded (mean length: 41 min).

2.3 Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the transcripts, with coding and analysis performed in Dedoose (Braun and Clarke 2006; “Dedoose Version 7.1.13: Web application for managing analyzing presenting qualitative mixed method research data” 2016; Vaismoradi et al. 2013). An initial codebook was developed inductively through analysis of the first two transcripts by two members of the research team (TS and RL) (Attride-Stirling 2001; DeCuir-Gunby et al. 2011). A third transcript was then double coded by the same two individuals, and three members of the research team met to adjudicate the codebook until consensus was reached (TS, RL, AH). The first author (TS) coded all of the remaining transcripts, with inter-rater reliability checks done at two different points between TS and RL after eight completed transcripts, and after the final 15th transcript. Inter-rater reliability checks were completed using Dedoose’s testing system, which pulled coded quotes to present to RL to code independently. Cohen’s kappa interrater reliability scores were 0.78 and 0.72, which are considered good reliability (Landis and Koch 1977). The codebook was revised iteratively as new concepts emerged from the interviews, and prior interviews were re-coded. Emerging concepts were identified by TS from clustering of codes and discussed with the entire research team. Through this process, domains and subthemes were defined.

No new themes emerged in interviews 14 and 15 and as such, data collection stopped after interview 15.

3 RESULTS

Of the 15 participants, a majority were Caucasian, male, and middle-aged (Table 1). Five individuals were diagnosed with LQTS and ten individuals with HCM.

| Agea | 40.0 (25–53) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 12 (80%) |

| Female | 3 (20%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 13 (87%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (7%) |

| Mixed ethnicity | 1 (7%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| HCM | 10 (67%) |

| LQTS | 5 (33%) |

| Years since diagnosisa | 8.2 (1–28) |

- a Data expressed as mean (range)

Individuals participated in a variety of exercise and sports activities, including running, biking, weightlifting, skiing, martial arts, and basketball. Four individuals had participated at some point in elite activities, defined as national or intercollegiate sports. A majority had participated in sports competitively in high school and recreationally as adults (Table 2).

| Prior to diagnosis | At the time of study | |

|---|---|---|

| Identify as athlete | 12 (80%) | 6 (40%) |

| Identify as active individual | 14 (93%) | 12 (80%) |

| Participation in competitive athletics | 10 (66%) | 5 (33%) |

| Intercollegiate or national team | 4 (26%) | 0 (0%) |

A majority (12/15) had previously self-identified as an athlete, but less than half (6/15) currently considered themselves an athlete.

3.1 Adherence to Recommendations

I participate in high impact sports that is not recommended – you know I forget exactly what it is that the recommendation is but basically I should not be running as much, I should not be playing ice hockey, and I should not be skiing if I recall so I think the better answer is I did not really change that much from an athletic perspective based on the doctor’s recommendation. Sorry just to be clear, I did take about 6 months off while we were trying to figure out what was going on and I was trying to decide what I was going to but once I made the decision not to follow recommendations I basically went back to my old ways - #1 [participant number], Male [sex], HCM [diagnosis], 40s [current decade of life], Hockey [activity discussed most during interview].

I could not even hardly imagine mountain biking and keeping my heart rate below 70%, so I definitely do not do that. I go out and I bike and I may bike a little less intense than I used to. Two things that I did [change after recommendations] is I used to have a bunch of interval work outs in my training – and I do not much of that anymore…I do not do any purposeful sprints…but I do not take the ‘keep it below 70 % max heart rate’ into account. I do not really abide by that. #2, Male, HCM, 50s, Mountain Biking

3.2 Rationale for Exercise Above Recommendations

The factors contributing to participants’ decisions to exercise above recommendations fall into four domains: the importance of exercise, perception of risk, personality, and social cues (Table 3).

| Domain | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Rationale for exercise above recommendations | ||

| Importance of exercise | I grew up playing, I played sports since I was ten I have been competitive all my life so …I need some sort of escape or release or whatever you want to call it and at the same time you know have that kind of challenge. So, I think that’s part of my make-up. #9, Male, HCM, 40s, Runninga | |

| Personal perception of risk | Assessed own risk as low | I did enough research into it and collected enough data that I felt comfortable that you can segment people with HCM into low risk, high risk, and very high risk based on a number of risk factors and then if you analyze the data based on risk factors you see a very big difference…in terms of the people who actually have sudden cardiac death situations and therefore I decided when I looked at the numbers – in terms of the probability of something happening to me to be so significantly below 0.1% #1, Male, HCM, 40s, Hockey |

| Acceptance of risk | I just kind of gauge it myself and figure hey if I am lifting this amount of weight and my heart gives out then whatever it probably would’ve given out if I was running up the stairs cause I was a couple minutes late to work or something. #4, Male, HCM, 30s, Weightlifting | |

| Protective measures | We purchased an external defibrillator. We took the precaution because we are a family that is active –#15, Female, LQTS, 40s, Fitness Classes | |

| Personality | [I told my doctor] ‘I am going to really need to get and maintain my metabolic fitness, right?...’ and she was like ‘walking’…I just do not know that she had ever encountered a particular patient like me who was just like really a dog after a bone and had had enough interactions with doctors that…I treated them with respect but not with awe - #3, Male, HCM, 40s, Martial Arts | |

| Social cues | I got to a point where I started hearing my buddies talk about playing sports, working out and I was like, no I am not going to work out. So [I had] these conversations with my wife. She’s encouraging me to get back in it, ‘It’s something that you love doing but just take it slow’. So that’s what I did really - #12, Male, HCM, 30s, Basketball | |

|

Rationale for modifying exercise Risk of death |

I basically made it [deciding to modify exercise] because of fear of losing my life really. My wife and I just had my first daughter a year earlier. So I was like it is really selfish of me to play on this basketball team that these guys have asked me to play on and then something bad happens? – #12, Male, HCM, 30s, Basketball | |

| Experience of symptoms | I’ve had several episodes where I’ve gone into a-fib, and I feel really, really bad when I’m at a-fib, and I’ve had to go in and get cardioverted…the first several times that I went into a-fib it happened while I was exercising. So again I went through this feeling like, “Oh, jeez I’m just going to have to give this up,” and that’s very, very upsetting. – #14, Female, HCM, 50s, Running | |

- a Quotes identified by participant #, sex of participant, diagnosis, and sport discussed most often in interview

3.2.1 Importance of Exercise

I have been running for so long that it’s incredibly difficult for me to not identify myself as a runner and not picture myself running. When I got into college and started running longer distances [I] realized that running was my escape from the stress of my day and a time where I could be out by myself and be in my own thoughts and process everything. I really used it as my outlet throughout all of my stressful times… it was the way that I managed everything else.

#8, Male, LQTS, 20s, Running

3.2.2 Personal Perception of Risk and Risk Reduction

All participants reported that their perception of the risk of a cardiac event as low or their actions to reduce risk influenced their decision to continue exercising above recommendations.

I did come across one study, I remember … a study looking into exercise and Long QT… there was a bunch of people with Long QT who disregarded the exercise restrictions…I think like only one of them had an episode and, I am not sure if it was while they were exercising. I looked at that and I thought, okay, well maybe it’s not super likely but also, I do not want to just be seeking out articles that may confirm that I can exercise.

#10, Male, LQTS, 20s, Skiing

I think if I had a cardiac event during exercise that would change my outlook somewhat and make me a little bit more fearful but like I said before, I have never associated any cardiac events with exercise, so I guess right now I am still pretty laid back about it.

#13, Male, LQTS, 20s, Weightlifting

“It’s a risk I’m willing to take…just like I’m willing to take the risk that I’ll get hit by a car.”

#10, Male, LQTS, 20s, Skiing

[I stopped hockey but] for biking it’s easy enough for me to stop when I get the top of a hard climb or something like that I spin down, I take it easy at the top for a little bit and I modify my behavior to avoid [over exertion]. I think the doc may have suggested that either a warm up before and maybe a cool down I am not positive… the sports that I have maintained doing I can actually do a cool down at the end and I eliminate the risk of this.

#4, Male, HCM, 30s, Biking

3.2.3 Personality

About of half of participants (7/15) indicated that their personality made them more prone to not following recommendations, describing themselves as stubborn, defiant or as “the type of person to question a doctor’s advice.”

Some individuals did not explicitly say personality characteristic played a role in their decision, but the language they used implied specific emotional reactions, which influenced their decision-making. For example, one participant described being more motivated to exercise after hearing strict recommendations to “prove him [the provider] wrong.”

Personality is also linked to other themes discussed above, such as how individuals perceive risk. Some individuals in general are predisposed to have more or less risk tolerance or need their own data to make decisions.

As described in the “Importance of Exercise” section, participants found exercise essential due to many reasons, such as its contributions to identity, achievement, and benefits to mental health. Implicit in these statements is that these individuals are the type of people to gain these benefits from exercise. Their personalities predisposed them to get significant benefit out of exercise activities.

3.2.4 Social Cues

Many participants (12/15) indicated that social cues contributed to their decision to continue exercising. This included family members encouraging them to stay active, participating in group or partner sports, learning that other people with their disease exercise above recommendations, and seeing negative outcomes in unhealthy people who did not exercise. Family members encouraged participants to exercise because they knew the vital role it played in their lives. Earlier in the section “Importance of Exercise,” participants discussed the social connections they maintained through their exercise activities. The group dynamics of exercise also can cause increased intensity in activity. A few participants discussed how they pushed themselves harder than they would have alone to keep up with their old teammates, running partners, or weightlifting partners.

Learning that other individuals with these diseases exercise above recommendations is both a social cue and a contributor to perceiving exercise as low risk. The realization that other individuals exercise above recommendations without cardiac events can influence risk perception.

A few individuals discussed seeing family members who did not exercise, and had perhaps gained weight or seemed less physically able than expected, and wanting to avoid similar outcomes for themselves. For individuals who find physical health essential, seeing people with negative physical health repercussions after stopping exercise is likely a strong influence.

Some participants reported working with a healthcare provider who they perceived to become more lenient with recommendations over time (5/15). Participants also mentioned clinicians discouraging a sedentary lifestyle made them feel justified in continuing exercise.

3.3 Rationale for Modifying Exercise

The reasons individuals modified their exercise or considered following recommendations generally fell into two domains: the risk of sudden cardiac death and the experience of having cardiac symptoms (Table 3). All participants considered these factors when making decisions about exercise and, for those who made modifications, these were motivating factors.

3.3.1 Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death

I stopped doing the races, I decided that it was too dangerous. I did them because I liked them, I did not have to. It was slightly disappointing but I thought I want to keep living so I am going to try to be smart about this. It seemed unwise…and once I decide it was unwise, I could not do it anymore.

#7, Male, HCM, 40s, Soccer

3.3.2 Experience of Symptoms

Some individuals (6/15) reported cardiac symptoms were a reason to consider modifying exercise. Participants noted that their decision-making was influenced by both nonspecific symptoms, such as palpitations or feeling dizzy, as well as specific symptoms, such as receiving implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks or frank syncope. Participants mainly discussed episodes that had occurred during exercise, though a few mentioned a general increase in symptoms.

3.4 Psychological and Social Impact

It was incredibly upsetting at the time. I was a teenager who had had this mysterious kind of medical event that was initially not clearly diagnosed and then I was being told that I had a genetic heart condition and then I was being told that I could not do the activities that I’d previously done for the past decade.

#5, Female, LQTS, 30s, Running

There was a while when I played I lost my enjoyment [of soccer] because I’d think okay is this my last run up and down the field. That took away all the joy, so I decided either ‘I’m going to do this and not worry about it’, or ‘I’m not going to do it’. I decided with the running, ‘I’m not going to do it’ and I decided with the soccer ‘I am going to do it and I’m not going to worry about it’. And so I got my head straight about it.

#7, Male, HCM, 40s, Soccer

Several participants felt sadness in receiving the recommendations, and some felt varying levels of anxiety while exercising above recommendations. Thus, both receiving recommendations and the process of exercising over recommendations could cause negative emotions.

[My family is] pretty supportive of me. My dad would probably be a little bit more hesitant. He’s more one that [feels], ‘Okay, swimming is the bad thing to do. Don’t swim. You shouldn’t swim.’ Mom is like, ‘Just don’t tell your dad you’re swimming.’ Really, it’s just him.

#15, Female, LQTS, 40s, Fitness classes

I feel like my cardiologist has been good in our interactions in that he admits that the science behind this is not very well developed…I feel like he’s been open and honest in saying we really do not know exactly to what extent I can exercise you know. He does not say you can or you cannot. It’s more like well you should not exercise too strenuously. He does not pretend that there’s certainty when there is not any. So I have found this very positive.

#7, Male, HCM, 40s, Soccer

Some participants (8/15) had worked with providers they felt lacked empathy on this topic or appeared unnecessarily strict, which made the emotional adjustment to recommendations more difficult or caused a lack of trust in the providers’ care. One participant specifically changed providers due to interactions with the provider about exercise recommendations. The participant felt the provider did not appreciate the added difficulty caused by the exercise recommendations.

4 DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrates there is gradation in the extent to which patients follow exercise recommendations, even among the least adherent individuals. Most individuals who self-identify as not following exercise recommendations make some modifications to their exercise regimen in response to recommendations, even if they do not follow the recommendations completely. This is particularly notable given that our goal was to recruit individuals who were the least adherent to exercise recommendations.

Most individuals reported some distress regarding the recommendations and a quarter of participants reported either significant emotional impact on themselves or strain in their relationships. Previous literature has shown that individuals who have restricted their activities report emotional distress, and our study adds that some individuals exercising above recommendations experience emotional distress from sadness upon learning of the recommendations, as well as anxiety as they continue to exercise (Asif et al. 2015; Luiten et al. 2014; Reineck et al. 2005). For some, this distress was ameliorated by continued participation in exercise activities.

Study participants were adults participating in recreational sports and had varied reasons for exercising above recommendations. Physical health benefits, such as maintaining body weight, continued to be important despite the potential for negative physical repercussions in a sudden cardiac event. The role these activities played in mental health, participants’ sense of self and social life, all contributed to continued activity after diagnosis. The variety of benefits and depth of meaning people derived from exercise is notable. Many of these benefits are critical components of a fulfilled life, such as interpersonal connections and creating identity. Individuals’ personalities played an independent role in decision-making, but also contributed to the other themes described. A participant’s personality could also cause them to be more likely to accept risk or to gain significant benefit from exercise activities. Participants were unwilling to relinquish these benefits due to their perception of the level of risk. Multiple individuals discussed personal factors they believed lowered their risk, such as having a defibrillator, adjusting their exercise, or lacking symptoms. Some of these factors are known to be associated with lower risk (e.g., lack of syncope, ICD, beta-blockers in LQTS), while others have no or only limited data regarding their impact on sudden death in HCM or LQTS (wearing a heart rate monitor, modifying diet, the fact that symptoms occur at rest but not with exercise). Genetic counselors, nurses, and cardiologists should be aware of what factors patients consider risk-reducing and provide available data on risk reduction of sudden cardiac events so patients can make informed decisions about risk-reducing behaviors.

4.1 Practice Implications

Clinicians have different approaches when discussing exercise recommendations with active individuals. While management recommendations for LQTS and HCM have included avoidance of certain types of exercise, there has been a lack of data on the magnitude of risk associated with exercise. Recent preliminary studies have shown patients with LQTS and HCM who exercise above guidelines and are on proper management have minimal ICD discharges and no excess of cardiac events (Aziz et al. 2015; Johnson and Ackerman 2013; Lampert et al. 2013). These emerging data have led multiple experts to shift their philosophy from rigid exercise recommendations to a shared decision-making model when counseling patients about exercise recommendations (Ackerman 2015; Afshar and Bunch 2017; Baggish et al. 2017; Cheung et al. 2016; Etheridge et al. 2018; Law and Shannon 2012; Rizvi and Thompson 2002). However, the allowance of competitive sports for individuals with HCM and LQTS is a subject of debate. The European guidelines are stricter than recent Bethesda guidelines, the European guidelines are without an option to return to competitive sports (Pelliccia et al. 2005). Some experts have questioned if athletes can truly make informed decisions or would ever choose to self-restrict activities they have a great personal investment in (Pelliccia 2014).

Shared decision-making emphasizes an informed decision made by the patient, facilitated by the healthcare provider (Charles et al. 1997). This approach has been taken with other healthcare decisions faced by individuals with HCM and LQTS, such as ICD implantation (Lewis et al. 2014). In a cohort of 157 individuals with LQTS participating in competitive sports, 83% elected to continue and 17% elect to discontinue sport participation after exercise recommendations were given in a shared decision-making context (Johnson and Ackerman 2013). Within cardiovascular genetics, shared decision-making about exercise can be facilitated by the cardiologist, nurse, genetic counselor, or, when needed, psychologist (Caleshu et al. 2016; Rhodes et al. 2016). Our data both support a shared decision-making approach and can inform how clinicians navigate such discussions with their patients. A shared decision-making approach can lead to an individual care plan that is better suited to a particular patient, and the particular benefits they gain from exercise, and a plan created in this way may be more likely to be followed. Our data showed that some participants changed providers due to the way the discussion of exercise recommendations was approached. Participants weighed risk in their own personal context and even those who exercised above recommendations did in fact choose to make modifications to their exercise. Many of our participants undertook independent evaluation of medical literature or information available on online communities, and then made assessments of their exercise plan. This shows that individuals may be open to making a change, dependent on the information they receive about the diagnosis and risks. A shared decision-making approach would allow providers to clarify patients’ understanding of information received through other sources and find areas where modification is possible. Open communication allows for a plan that is feasible for the patient as compared to a strict dictation that causes patients to dismiss a provider entirely or disengage from finding a compromise.

Participants in our cohort were actively making decisions about exercise months or years from when they were first given the restrictions, due to needing time to acclimate to their diagnosis, changes in lifestyle unrelated to their diagnosis, or new onset of symptoms. This highlights the need for continued discussions about the exercise recommendations over time with healthcare professionals who can help patients consider the exercise recommendations in light of their current values, priorities, and circumstances.

Cardiovascular genetic counselors would be prime clinicians to navigate shared decision-making conversations. These complicated decisions require patient education and weighing of risks and benefits. Genetic counselors are trained to elicit patient values and help contextualize these values to make potentially emotionally distressing medical decisions. Some patients may not be able to communicate their deep attachment to these activities as eloquently as our quoted participants. The data in this paper could help providers who have limited participation in sports activities empathize with patients.

4.2 Study Limitations

A majority of participants were interviewed many years after their initial diagnosis, so their responses are prone to recall bias. Recruitment depended largely on clinicians’ recall, which may have biased the sample. Participants were recruited from major academic institutions that may present recommendations differently than in other practices. Data was not available on what recommendations participants were given, and it is likely participants were given different recommendations given the variance in time and providers in our sample. Participants were asked to describe the recommendations they received, but most participants vaguely recalled the recommendations; thus, we could not distinguish if guidelines differed significantly between patients. The different institutions participants were recruited through may attract a different patient population. Participants were primarily Caucasian and male; the perspectives of other groups may differ and are not well represented in our data. Education level was not collected and may have influenced how participants interpreted and evaluated the recommendations. We did not collect data on disease severity or whether participants have an ICD. Notably, our sample does not include adolescents or adult athletes currently engaged in varsity, collegiate, or professional sports, so our data cannot speak to the perspectives of those groups, which are likely different from those of our study population of adults who were participating in recreational sports.

5 CONCLUSION

Active adults with HCM and LQTS who exercise above recommendations do make some modifications to their exercise regimens. Participants’ decisions regarding exercise evolve, underscoring the importance of conversations beyond the initial evaluation. Key motivators in their choice to exercise above recommendations include the vital part exercise plays in their lives and their perceptions of risk of sudden death as either low, acceptable, or modifiable. Some participants believed their risk of sudden death was lower or modifiable based on reasoning that is not necessarily supported by medical research. Clinician understanding of patients’ motivations can facilitate shared decision-making regarding exercise recommendations.

6 AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

Trishna Subas contributed to study design, collection of quantitative data, conducted participant interviews, developed and revised the codebook, analyzed data, wrote and revised drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. Rebecca Luiten contributed to study design, collected quantitative data, revised the codebook, edited manuscript drafts, and approved the final manuscript. Andrea Hanson-Kahn contributed to study design, assisted with codebook revisions, edited manuscript drafts, and approved the final manuscript. Matthew Wheeler contributed to study design, discussed emerging themes, edit manuscript drafts, and approved the final manuscript. Colleen Caleshu contributed to conceptualization of the project and study design, edited manuscript drafts, analyzed data, and approved the final manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the research presented.

7 COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of Interest Trishna Subas, Rebecca Luiten, Andrea Hanson-Kahn, Matthew Wheeler, and Colleen Caleshu declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human Studies and Informed Consent All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal Studies No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was done with the support of the Stanford Genetic Counseling program as the first author was a trainee at the time of the study. The work was conducted as part of the first author’s graduate genetic counseling training. The authors thank the participants for donating their time and sharing their experiences and Dr. Sylvia Bereknyei and Dr. Janine Bruce for their assistance with qualitative methodology.