Effects of preoperative walking on bowel function recovery for patients undergoing gynecological malignancy laparoscopy

Abstract

To investigate effects of preoperative walking on bowel function recovery for patients after gynecological malignancy laparoscopy. The 156 patients with gynecoligical cancers after laparoscopy in Jiangsu from June 2020 to September 2021 were selected as research subjects, who were randomized into an experimental group (n = 78) and a control group (n = 78). Both of the groups received routine nursing care during the study. In addition, the experimental group underwent low-moderate intensity walking exercise 1 week before surgery. The bowel function (including the time of first defecation, the time of first passage of flatus/”gas-out time” and the recovery time of bowel sound), adverse events (nausea, vomiting abdominal distension and abdominal pain), as well as postoperative complications (ileus symptoms, deep venous thrombosis, infections and etc.), were measured daily. The time of first defecation, the time of first passage of flatus and the recovery time of bowel sound in experimental group were less than the control group after treatment (p < .05). Repeated measures analysis of variance showed that the adverse reactions (nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and ileus symptoms) of the experimental group were weaker than those of the control group at different time points after the intervention (p < .05). Walking before surgery can effectively promote the recovery of bowel function and reduce the adverse reactions, as well as the risk of ileus related to gynecological malignancy laparoscopy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal dysfunction is one of the most common complications after gynecological oncology laparoscopy, along with the incidence of postoperative nausea up to 50%, vomiting about 30%,1 and paralytic ileus between 12.9% and 32%.2 Thus, it seriously affects the postoperative recovery of patients, delays the discharge time and increases the hospitalization expenses. In addition, it may also lead to the occurrence of serious complications such as hospital-acquired infection, pneumonia with deep venous thrombosis, and reduce patients quality of life and postoperative satisfaction.3 Therefore, it has become an important goal of perioperative management to promote the recovery of postoperative intestinal function, reduce complications and shorten the hospital stay after laparoscopic surgery. Currently, various strategies have been adopted clinically to manage intestinal function. For example, in Western medicine, most of the methods such as pro-gastric motility drugs, multimodal analgesia, postoperative gum chewing and coffee drinking, gastric motility drugs and ultrasonic physiotherapy are used,4, 5 as well as in traditional Chinese medicine, auricular massage, acupuncture, herbal tonics or herbal enemas are used.6, 7 However, the scope of application is limited due to factors such as perioperative fasting and medication, adverse drug reactions, and cumbersome Chinese medicine operations. In recent years, the concept of accelerated rehabilitation surgery has been gradually gaining attention in the field of gynecological perioperative management. It is recommended that patients should get out of bed early after operation, which can prevent postoperative intestinal obstruction and promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function.8

However, there are few reports on whether preoperative exercise in improving effectively intestinal function through systematic literature retrieval.9, 10 Therefore, in this study, the preoperative walking protocol is appilied to patients with gynecological malignancy who plan laparoscopic surgery to explore the impact on the recovery of postoperative intestinal function, in order to provide clinical reference.

2 OBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1 Research objects

Using the objective sampling method, 156 patients admitted to the department of gynecological oncology in a tertiary first-class hospital for laparoscopic surgery from March 2020 to September 2021, were selected and divided into the experimental group and the control group according to the random number table method. Inclusion criteria: (1) pathological diagnosis of gynecological malignancy (including cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer); (2) laparoscopic surgery is planned; (3) Age ranged from 18 to 65 years; (4) having smart phones; (5) patients voluntarily participated in this study and signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with malignant fluid in the late stage of malignant tumor were changed to open operation during operation; (2) the surgery involves upper abdominal organs; (3) preoperative intestinal obstruction and intraoperative intestinal injury; (4) liver and kidney dysfunction before surgery; (5) complicated with chronic gastrointestinal function discomfort or gastrointestinal organic lesions; (6) postoperative complications or serious infection; (7) Accepted other treatments to promote the recovery of intestinal function; (8) those who have participated in other drug trials or research projects. This study has been approved by the hospital ethics committee.

2.2 Research methods

2.2.1 Intervention plan of the experimental group

Set up a sports steering group

The members of the sports guidance group include: (1) one instructor, who is the head nurse and chief nurse in the ward, responsible for the overall control of the research. (2) There are two supervisors, one is a ward nurse with undergraduate and nurse titles, and the other is a graduate student. They are responsible for explaining the purpose and precautions of the study to patients, downloading pedometer APP, teaching patients how to use it, supervising and recording relevant data. (3) There are two investigators, both of whom are ward nurses with undergraduate and nurse professional titles. They are responsible for collecting baseline data and post-intervention evaluation indicators. (4) There are two doctors, both of whom are postgraduates, with the titles of deputy chief physician and attending physician, respectively. They are responsible for answering patients' questions and providing guidance related to walking exercise to ensure patients' exercise safety.

Pedometer software and the use of WeChat groups

Establish a WeChat punch-in group for walking exercise. After the patients joining in the experimental group were enrolled, they were immediately drawn into this group. The supervisor assisted the patients to download the pedometer APP (used to record the daily steps and exercise heat energy consumption), and ensure that the patients and their families mastered the pedometer APP. In addition to sleeping and bathing, patients were instructed to carry mobile phones with them and send screenshots of daily pedometer steps and calorie consumption are sent to the WeChat group.

Implementation of preoperative walking exercise

- Preintervention education: after the patients are enrolled in the group, the supervisor will issue the exercise instruction manual and carry out exercise education, including the benefits, principles and precautions of exercise. (1) Exercise time: it is advisable to conduct after the end of treatment or 0.5–1 h after meals every day for 20–30 min. If the patient cannot complete it at one time, it can be carried out in sections for at least 10 min each time. (2) Exercise intensity: use low and medium exercise intensity, that is, 90–120 steps/min,12 and teach patients to measure their heart rate by themselves. It is inappropriate to exceed 50%–60% of the maximum heart rate (220 minus age) or subjectively feel slight sweating and fever;13 (3) Precautions: according to the individual situation of patients, it should gradually increase the amount of exercise to prevent excessive fatigue and reduce autoimmune function, pay attention to the weather changes, and replenish water properly before and after exercise. The supervisor instructs the patients how to use the pedometer APP correctly, and monitor the patient's daily walking activity and calorie consumption.

- Implementation of intervention plan: the supervisor goes to the bedside at 8:00 every day to remind the patients of the amount of walking exercise, and reminds the patients who have not met the requirements of walking exercise that day at 17:00 to encourage the patients of completing the exercise goal at night. The doctor asks and observes the patient's discomfort during exercise everyday upon ward round, and gives exercise guidance. In Wechat group, the doctor cares about the patient's condition and answers her questions at any time. In case of adverse weather affecting going out, it is recommended that the patient complete walking exercise in the hospital.

2.2.2 Intervention methods of control group

The supervisor distributes the exercise instruction manual, assists them to download the same pedometer software APP, conducts exercise education, instructs them to carry their mobile phones with them, and establishes a WeChat group to monitor the daily walking exercise of patients. Doctors are always concerned about the patient's condition and answer their various questions.

2.3 Evaluation index and data collection method

The evaluation indexes included the first postoperative exhaust and defecation time, the recovery time of bowel sounds, the postoperative hospital stay, the incidence of gastrointestinal adverse reactions (abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain) and the incidence of complications.

The first postoperative exhaust and defecation time refers to the time from the end of the operation to the first exhaust and defecation. A postoperative observation table is placed at the end of the patient's bed, which is recorded by the patient and her family members. The nurses on each shift inquire about the implementation in time. The recovery time of bowel sounds refers to that starting from 6 h after operation. The investigator listens to bowel sounds every 2 h with a stethoscope, 1 min/time, until the bowel sounds recover. Taking 3–5 times/min as the index of bowel sound recovery, the time and number of bowel sounds were recorded on the postoperative observation table.

The occurrence of gastrointestinal adverse reactions was evaluated on postoperative day 1 and continuously for 3 d. The evaluation contents are as follows: (1) The evaluation criteria of nausea,14 vomiting and abdominal distension after laparoscopic surgery are scored to different degrees according to the routine of Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Diseases: 0 point for asymptomatic patients, 1 point for mild symptoms, 2 points for moderate symptoms and 3 points for severe symptoms. (2) Abdominal pain was evaluated according to Prince Henry pain scoring standard:15 0 point for no pain when coughing, 1 point for pain only when coughing, 2 points for no pain when resting and pain only when breathing deeply, 3 points for pain and tolerable in quiet state, and 4 points for severe pain and unbearable in quiet state.

The observation of complications mainly includes postoperative intestinal obstruction, deep vein thrombosis and the occurrence of infection. Firstly, diagnostic criteria for intestinal obstruction:16 there are four symptoms: abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distension, stopping defecation and exhaust. Intestinal type or peristaltic wave and hyperactivity of intestinal sounds can be seen in the abdomen. At the same time, the diagnosis is made in combination with abdominal plain film. Secondly, the diagnostic standard of deep venous thrombosis was that vascular ultrasound indicates deep venous thrombosis. Finally, criteria for postoperative infection: (1) superficial incision infection: (1) postoperative incision has red, swollen, hot, painful and inflammatory manifestations, or there is purulent secretion at the incision, (2) the postoperative leukocyte count was greater than 10 × 109/L, (3) the body temperature reached or exceeded >38°C twice within the first 2 days after surgery. Compliance with any of the above is surgical superficial incision infection. (2) Deep surgical site infection: (1) puncture or drainage to pus from deep surgical site, (2) natural dehiscence or intentional opening of the surgical incision by the surgeon, purulent secretion or fever >38°C, local pain or tenderness, (3) surgical exploration was performed again, and re-operation exploration of deep incision abscess or other signs of infection by histopathological or imaging examination, (4) positive culture of purulent drainage bacteria. Compliance with any one of the above items is a deep surgical site infection. Postoperative infection rate = (cases of superficial incision infection + cases of deep surgical site infection) / total cases ×100%.

2.4 Quality control

All patients received similar preoperative treatment and nursing, including fasting, water deprivation and mechanical intestinal preparation at 22:00 1 day before operation (one box of compound polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder plus 1000 ml warm boiled water, once at 15:00 and 17:00, respectively). Intravenous prophylactic antibiotics were administered 30 min before surgery. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia laparoscopy, induced by sufentanil, midazolam and propofol, and maintained by intravenous and inhalation combined anesthesia. The surgical procedures were extensive hysterectomy or total hysterectomy with pelvic lymph nodes and abdominal para-aortic lymph node sampling, plus omentum, and appendectomy in ovarian cancer patients. Within 48 h after the operation, the abdominal girdle was tied, ondansetron was used for antiemetics, an intravenous analgesic pump was routinely used, and nonsteroidal analgesics were given only when necessary. The patients were encouraged to get out of bed as soon as possible without using drugs or physical therapy to promote the recovery of intestinal function, such as opioid receptor antagonists or ultrasonic physiotherapy. In order to reduce bias as much as possible, the postoperative eating pattern is also relatively fixed: the first liquid diet is given in the morning of the first day after operation, then semi-liquid diet is given until anal exhaust, and then semi-solid diet is given. Parenteral nutrition was routinely administered postoperatively until the patient could tolerate semisolid food.

Before the trial, the supervisors and investigators should be trained uniformly to clarify the methods of baseline data collection and postintervention indicators. The supervisors needed to master the use of pedometry software and supervision skills. Through choosing the step counting software with simple operation and data memory function, the supervisor could be clear of the portable situation of the patient's mobile phone at any time, and remind the patient by the bedside and WeChat group. More measures should be adopted, including establishing a good nurse–patient relationship, obtaining the trust and cooperation of patients, improving their compliance, and rewarding a small gift to patients, with completing the target amount of walking exercise. Additionally, it is necessary of organizing data in a timely manner, verifying all the data with complement in a timely manner. The data should be checked and rechecked if necessary to ensure accuracy.

2.5 Statistical methods

SPSS 26.0 software was used for statistical analysis. In this study, the measurement data met the normality and homogeneity of variance, and were described by mean standard deviation, with intergroup comparison adopting two independent sample t test. The scores of nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and abdominal pain at each time point were compared by repeated measurement analysis of variance. If the Mauchly's sphericity hypothesis test (p > .05) was satisfied, the within-subjects effect test was used, and if not, the multivariate test was used. Count data were described by frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact probability test, and rank sum test was used for rank data. The difference was considered statistically significant at p < .05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Comparison of general data between the two groups

A total of 156 cases were included in this study, with 78 cases in each group and no missing samples. There were 28 cases of cervical cancer, 24 cases of endometrial cancer and 26 cases of ovarian cancer in the experimental group, and 25 cases of cervical cancer, 30 cases of endometrial cancer and 23 cases of ovarian cancer in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference between the general conditions of the two groups (p > .05), which was comparable. See Table 1.

| Item | Control group (n = 78) | Intervention group (n = 78) | T value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 38.65 ± 8.39 | 39.87 ± 9.46 | 1.82 | .72 |

| Preoperative blood potassium (mmol/L) | 4.28 ± 3.03 | 4.49 ± 3.57 | 3.85 | .23 |

| Preoperative platelet (×109/L) | 121.05 ± 22.60 | 118.21 ± 28.55 | 1.87 | .39 |

| Operation time (h) | 2.92 ± 0.94 | 2.97 ± 0.96 | 3.25 | .18 |

| Anesthesia time (h) | 3.96 ± 0.31 | 4.03 ± 0.28 | 3.35 | .21 |

| Intraoperative bleeding volume (ml) | 45.12 ± 29.75 | 42.96 ± 34.10 | 4.70 | .18 |

3.2 Comparison of gastrointestinal function recovery between the two groups

After intervention, the first postoperative exhaust time, first defecation time and bowel sound recovery time of the experimental group were shorter than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (p< 0.01), as shown in Table 2.

| Group | Number | First exhaust time | First defecation time | Bowel sound recovery time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group | 78 | 23.86 ± 9.69 | 39.15 ± 12.4 | 16.60 ± 5.31 |

| Control group | 78 | 35.62 ± 10.85 | 52.84 ± 13.71 | 19.29 ± 6.56 |

| T value | 4.458 | 3.985 | 4.032 | |

| p value | .007 | <.001 | .008 |

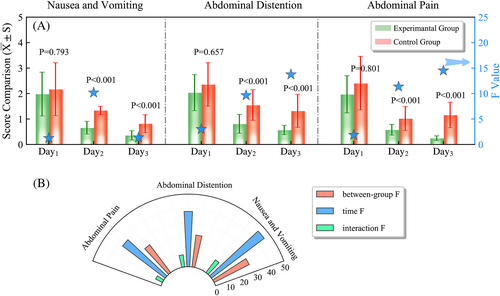

3.3 Comparison of adverse reactions between the two groups

The scores of nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and abdominal pain at different time points of the two groups were analyzed by repeated measurement ANOVA. The data met the results of Mauchly's sphericity test (p > .05). The results of the analysis showed that the three symptom scores were statistically significant between the two groups (p < .001), and the three symptom scores were statistically significant within the different time groups (p < .001). The interaction between group and time was also statistically significant (p < .001). See Figure 1.

3.4 Comparison of postoperative complications between the two groups

After the intervention, the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction in the experimental group was significantly lower than that in the control group (p < .001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of deep venous thrombosis, incision infection and abdominal infection between the two groups (p < .001), as shown in Table 3.

| Group | Number of cases | Intestinal obstruction | Deepvenous thrombosis | Incision infection | Abdominal infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test group | 78 | 8 (10.26) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.85) | 4 (5.13) |

| Control group | 78 | 34 (43.59) | 2 (2.56) | 3 (3.85) | 6 (7.69) |

| X2 | 22.025 | 0.506 | 0.000 | 0.427 | |

| p | <.001 | 0.477 | 1.000 | .513 |

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Preoperative walking can promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with gynecological tumors after laparoscopic surgery

In recent years, gynecological laparoscopic surgery has been widely used in the treatment of gynecological malignant tumors such as cervical cancer, ovarian cancer and other gynecological malignancies due to its advantages of low trauma, less bleeding and fast postoperative recovery. However, the nursing measures such as construction of artificial pneumoperitoneum, anesthetic drugs, traction and exposure of gastrointestinal tissue during operation increase the risk of gastrointestinal function damage. In addition, these could easily cause adverse effects such as postoperative abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and anus difficult defecation, which blocks the wound healing and affects the postoperative quality of life of patients.17, 18 The results of this study showed that the time to first defecation and bowel sounds after surgery was shorter in the experimental group than in the control group (p < .01), indicating that preoperative walking can effectively promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function of patients with gynecological tumors after laparoscopic surgery. A systematic evaluation indicated that preoperative exercise contributes to the recovery of postoperative gastrointestinal function.19 In addition, walking can promote the patient's multiple systems, enhance the parasympathetic tone, reduce the excitability of sympathetic nerve, promote the blood circulation of digestive organs, increase the secretion of digestive fluid and gastrointestinal hormones, strengthen the absorption and utilization of nutrients, enhance appetite, promote the synthesis and excretion of bile, and improve the function of digestive system.20 Besides, some studies have pointed out that walking can stimulate the gastrointestinal system, promote intestinal peristalsis, facilitate the elimination of intestinal contents, and shorten the time of elimination and defecation, thus promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function.21 Similar to Tan Qin's study on promoting gastrointestinal recovery through early postoperative exercise,22 this study developed a less difficult walking exercise program before surgery, which could greatly reduce the psychological burden of patients' reluctance to get out of bed due to postoperative incisional pain, improve acceptance, and increase compliance. Liu Linlin found that aerobic exercise 1 month before surgery can effectively shorten the postoperative exhaust and defecation time of patients with gastric cancer, which is consistent with present study.23 This suggests that the staff should pay attention to the preoperative exercise of patients and encourage patients to carry out low-to-moderate intensity walking exercise 1 week before surgery, so as to promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function after surgery.

4.2 Preoperative walking can reduce gastrointestinal disorders and other adverse reactions in patients with gynecological tumors after laparoscopic surgery

In this study, repeated measures analysis of variance was performed on the symptom scores of nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain in the two groups of patients at different time points after surgery. The results showed that the above adverse reaction scores in the experimental group were significantly lower than those in the control group (p < .001), indicating that walking exercise can effectively reduce the adverse reactions such as gastrointestinal dysfunction in patients with gynecological malignant tumors after laparoscopic surgery. Similar to Wang Yanle's research on reducing adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting and abdominal distension in patients with liver cancer surgery through personalized rehabilitation exercise program.24 Through a meta-analysis, Lau et al. also found that among many intervention measures for postoperative gastrointestinal disorders and other adverse reactions, exercise therapy could effectively reduce symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and abdominal distension, and the intervention effect was significant,25 and it was speculated to be related to the following factors. Regular walking at low-to-moderate intensity 1 week before surgery could effectively improve the autonomic nerve function of organs, educe the sympathetic excitability of digestive organs and improve the parasympathetic excitability. During walking, gastrointestinal movement was strengthened to stimulate the release of gastrointestinal hormones, enhance gastrointestinal peristalsis through humoral factors, and promote the recovery of the function of various body organs, thereby relieving postoperative nausea and vomiting, abdominal distension, abdominal pain and other symptoms.26 The exercise program was arranged before surgery, painless and easy to accept, simple, safe, economical and effective, which was conducive to strengthening physique and promoting early recovery. There was no significant difference in the scores of nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and abdominal pain between the two groups on the first day after operation (p > .05), which may be related to the slow intestinal recovery process and the intensity, time and amount of walking movement of patients after laparoscopic operation. Therefore, follow-up research is needed for further observation.

4.3 preoperative walking can reduce the incidence of intestinal obstruction in patients with gynecological tumors after laparoscopic surgery

Postoperative ileus may involve a variety of factors, including gastrointestinal inflammatory, neurogenic, and drug-induced mechanisms system.27 The acute stage of intestinal obstruction is generally caused by neurogenic stimulation, and peritoneal stimulation causes continuous excitation of vagus nerve, the duration is usually attributed to inflammatory stress response caused by tissue damage, the drug-induced mechanism mainly refers to perioperative periods use of drugs. It is necessary to inhibit normal intestinal peristalsis by affecting opioid receptors, for the above three mechanisms causing intestinal obstruction. Therefore, effectively improving patients' intestinal peristalsis can avoid the occurrence of intestinal obstruction to the greatest extent. At present, various methods have been used to reduce the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction, including oral Chinese medicine decoction,28 chewing gum,29 early postoperative eating.30 This study showed that the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction was significantly lower than that of the control group (p < .01), suggesting that preoperative walking can reduce the incidence of postoperative intestinal obstruction of gynecological malignant tumors after laparoscopic surgery, which is consistent with the results of Hu et al.31 This may be related to the fact that walking at low-to-moderate intensity can effectively stimulate the gastrointestinal system. In addition, studies have shown that regular and moderate exercise can accelerate the transit time of the rectosigmoid and total colon.32 However, the specific physiological mechanism of walking to stimulate peristalsis remains to be further studied.

5 CONCLUSIONS

preoperative walking can effectively improve the gastrointestinal dysfunction of patients with gynecological malignant tumors after laparoscopic surgery, shorten the recovery of bowel sounds, exhaust and defecation time, reduce adverse reactions such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension as well as with abdominal pain, and reduce the occurrence of complications such as intestinal obstruction. Moreover, the exercise is safe, less difficult, more acceptable, and has better compliance. Since this study is a single-center study, the sample size is small, patients in the same ward may have contamination, and the exercise volume is not graded. Thus, in the follow-up, it is necessary to expand the sample size, and try to design experimental groups with different exercise volumes to further explore the clinical efficacy and optimal dose of walking exercise, in order to provide reference for promoting the patients' rapid recovery.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: Xia Xiaoli, Ding Guirong, Shi Lingyun, Wang Meixiang, Tian Jing. Literature review and manuscript drafting: Xia Xiaoli, Ding Guirong, Tian Jing. Data analysis: Shi Lingyun, Wang Meixiang. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants for their contribution and their support of the study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 81702895).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.