Development of cefepime-induced encephalopathy in a patient with depression and rectal cancer: A case report

Abstract

Background

Cefepime, a fourth-generation cephalosporin, has neurotoxic side effects such as encephalopathy. Baseline conditions, including blood–brain barrier (BBB) impairment and renal dysfunction, are known to associate with elevated central nervous concentration of cefepime. Although BBB dysfunction occurs with depression or cancer, currently, neither is regarded as a risk factor for cefepime-induced encephalopathy.

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old woman with a history of depression and rectal cancer was hospitalized for a bacterial liver abscess. Brain metastasis and other causes for delirium were excluded, and no renal dysfunction was observed. However, 11 days after cefepime and metronidazole administration, the patient suddenly developed confusion, disorientation, and myoclonus, with no apparent changes on brain magnetic resonance imaging. Electroencephalography revealed a consistent tri-phasic wave pattern. Clinical symptoms were well consistent with cefepime-induced encephalopathy; hence, cefepime and metronidazole were discontinued, followed by rapid physical and mental recovery, with no aftereffects.

Conclusions

In terms of BBB dysfunction, depression and cancer might be possible occult risk factors for cefepime-induced encephalopathy. Doctors need to pay attention to encephalopathy risk when administering cefepime in patients with depression or cancer because the psychiatric symptoms of encephalopathy, depression, and delirium from other causes are often confusing, leading to misdiagnosis and a poor prognosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Antibiotics are widely used against bacteria or protozoa in clinical situations. Despite their effectiveness, antibiotics have severe and lethal neurotoxic side effects, represented by antibiotic-induced encephalopathy. Based on the clinical characteristics, antibiotic-induced encephalopathy are categorized into Phenotype 1 (cephalosporins and penicillin), Phenotype 2 (quinolones, macrolides, and procaine penicillin), and Phenotype 3 (metronidazole), respectively.1 It is pointed out that Phenotype 1 includes encephalopathy accompanied commonly by seizures or myoclonus arising within days after antibiotic administration, Phenotype 2 includes encephalopathy characterized by psychosis arising within days of antibiotic administration, and Phenotype 3 includes encephalopathy accompanied by cerebellar signs and MRI abnormalities emerging weeks after initiation of antibiotics.1

Cefepime, a fourth-generation cephalosporin approved for clinical use in 1996,2 has a broad-spectrum coverage against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae with AmpC β-lactamase. These bacteria are potential agents of healthcare-associated infections and neutropenic fever.3 Although cefepime-induced neurotoxicity was first reported in 1999,4 its pathophysiological mechanism remains elusive. Notably, both renal dysfunction and impaired blood–brain barrier (BBB) are considered potential risk factors for cefepime neurotoxicity because both eventually lead to increased central nervous system concentration of cefepime.5

In this paper, we report for the first time on cefepime-induced encephalopathy in a patient with depression and rectal cancer. Renal dysfunction was not observed during treatment, and depression and cancer were suspected as occult risk factors for cefepime-induced encephalopathy, especially in terms of BBB dysfunction.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 79-year-old woman had an onset of cefepime-induced encephalopathy. The patient had no developmental problems, and the last education level was at a local high school. At 75 years, she was diagnosed with rectal cancer with metastasis to the liver. Laparoscopic low anterior resection following partial liver dissection (S1 and S4) was performed within several months of the diagnosis. Postoperatively, chemotherapy with irinotecan (140 mg/day, intravenous), tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (100 mg/day, intravenous), and cetuximab (600 mg/day, intravenous) was initiated. However, several months postoperatively, she gradually developed symptoms that were reasonable for a diagnosis of depression, including depressed mood, loss of interest, sleep disturbance, psychomotor retardation, fatigue, and sense of worthlessness which persisted for >2 weeks. Her medical history included hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. Her Hasegawa Dementia Scale-Revised6 (HDS-R) score was 27/30, indicating no apparent cognitive dysfunction. She was then referred to the first author, a trained psychiatrist, and a diagnosis of major depressive disorder was made. Mirtazapine (15 mg/day, oral) and lorazepam (0.5 mg/day, oral) were initiated, and the depressive symptoms gradually subsided within 2 months. Her depressive symptoms were subsequently almost stable for 4 years, although she felt anxious about her future and became sometimes depressed after chemotherapy. Mirtazapine and lorazepam continued to be used during that period with no change in dosage.

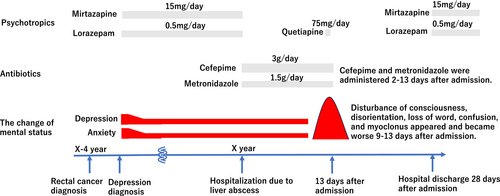

At 79 years, she was hospitalized for fever and right abdominal pain, and liver abscess was diagnosed based on the abdominal computed tomography findings. Her vital signs on hospitalization were as follows: temperature, 38.5°C; blood pressure, 143/76 mmHg; and pulse, 98/min. The patient was awake and alert, with no apparent psychiatric or neurological symptoms. Percutaneous transhepatic abscess drainage was performed 1 day after admission. Cefepime (3 g/day, intravenous) and metronidazole (1.5 g/day, intravenous) were administered to treat the bacterial liver abscess 2–13 days after admission. Mirtazapine and lorazepam were discontinued, considering her unstable general condition and the risk of drug-induced delirium.7, 8 Her fever gradually improved, and her general status stabilized. However, 10 days after admission, anxiety, irritation, and insomnia were reported (Figure 1). The surgeon in charge regarded these symptoms as depression aggravation, and we were asked to manage her psychiatric symptoms. When we met her 10 days after admission, restlessness, agitation, severe insomnia, and slight disorientation were noted. We initially diagnosed her as delirium due to physical problems and not depression aggravation, although the inflammatory response peak had already passed. Then we initiated quetiapine (75 mg/day, oral) to cope with her psychiatric symptoms.

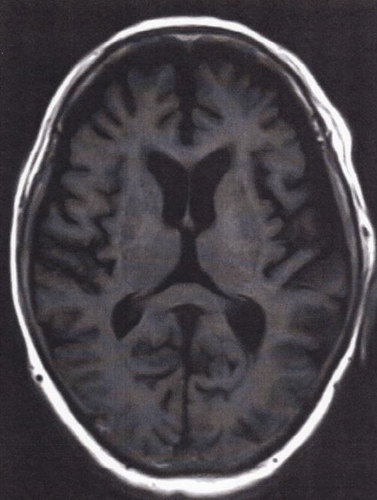

However, on Day 11, altered mental status aggravated and myoclonus appeared irregularly. Quetiapine was discontinued after 1 day to avoid complications. This was not ordinary delirium, and cefepime-induced encephalopathy was suspected based on the clinical symptoms and their emergence timing. No NH3 elevation was observed, and the liver function was maintained (Table 1). Renal function was normal, and brain MRI showed no brain metastasis, hydrocephalus, or hemorrhage (Figure 2). Moreover, no change of cerebellar dentate nuclei was observed, which is usually found in more than 90% of metronidazole-induced encephalopathy cases.9

| Days after admission | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 |

| AST (U/L) | 28 | 19 | 24 | 19 | 21 | 26 | 28 | 38 |

| ALT (U/L) | 9 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 6.2 | 8.9 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 15.3 |

| Cre (mg/dL) | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.6 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.5 | 0.76 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 6.61 | 17.89 | 29.63 | 24.35 | 7.86 | 6.18 | 3.64 | 3.39 |

| NH3 (μg/dL) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 23 |

| Ascites | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

- Note: NH3 was kept within normal limit. No renal or liver dysfunction, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy was admitted.

- Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; NH3, ammonia; T-Bil, total bilirubin.

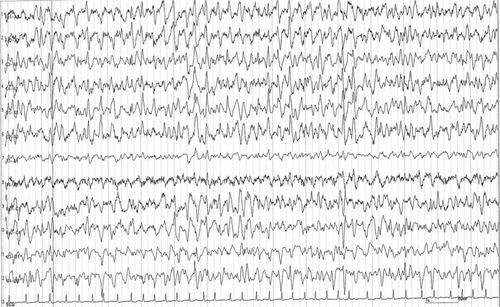

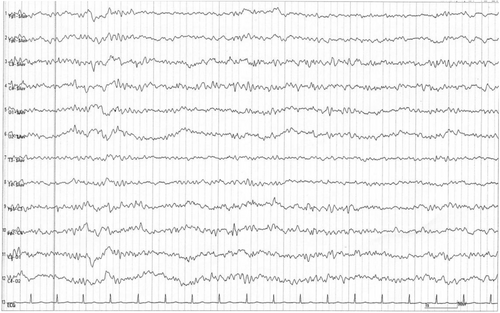

Electroencephalography (EEG) was performed 12 days after admission, revealing a generalized periodic discharge, fluctuating and changing into a delta pattern at a frequency of 3–4 Hertz (Figure 3). The general morphology of the discharge contained a continuous wave pattern, comprising sharp negative components, followed by a broader positive amplitude and a negative slow waveform. These characteristic EEG findings suggested consciousness disturbance, and its consistent tri-phasic wave pattern was estimated to be derived from cefepime neurotoxicity.10 Based on the psychiatric symptoms and EEG findings, cefepime was regarded as the most likely cause, and a diagnosis of cefepime-induced encephalopathy was made.

After cefepime and metronidazole were discontinued on Day 13, the patient regained her baseline alertness and was oriented toward time, place, and person the next day. A repeat EEG on Day 15 demonstrated apparent improvement in the delta and tri-phasic wave patterns (Figure 4). Rapid and remarkable improvements in the patient's consciousness, mental status, and EEG findings strongly supported the diagnosis of cefepime-induced encephalopathy. The drainage tube was removed on Day 15. The patient recovered well and was discharged on Day 28. When the patient was seen at the first author's outpatient clinic 2 weeks after discharge, her consciousness was clear and no worsening of her depression was admitted. Thereafter, the patient restarted receiving regular outpatient treatment at the hospital.

3 DISCUSSION

The typical clinical symptoms of cefepime-induced encephalopathy include altered mental status (93%), myoclonus (37%), and non-convulsive seizure epilepticus (NCSE) (28%),5 with normal brain MRI findings.1 The symptoms ameliorate soon in 97.5% of cases by dose reduction or discontinuation of cefepime, and the median time-to-improvement is 3 days.5 Regarding cefepime-induced encephalopathy onset, symptoms typically occur approximately 5 ± 4 days after administration.1 This case presented these clinical characteristics, verifying the diagnosis as cefepime-induced encephalopathy. Renal disease is considered the most common etiology, and its incidence is as high as 89.9% in cefepime-induced encephalopathy cases.5 Ugai et al.11 reported that renal function with creatine clearance <30 mL/min is significantly associated with cefepime-induced encephalopathy development in patients with hematological malignancies.

Moreover, cefepime-induced encephalopathy occasionally develops in patients with normal renal function or those receiving appropriately adjusted cefepime doses, indicating that BBB impairment as well as renal dysfunction may significantly contribute to the onset.5 As for BBB impairment, neurological diseases associated with cefepime-induced encephalopathy include stroke, mild cognitive impairment, seizure, cerebral palsy, intracranial hemorrhage, Parkinson disease, and neuromyelitis.5 In these diseases, it is speculated that the onset of cefepime-induced encephalopathy is linked to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor disturbance.1 It is hypothesized that neurotoxicity is linked to the suppression of inhibitory neurotransmission via GABA antagonisation,12 subsequently resulting in BBB dysfunction and increased central nervous system concentration of cefepime.13

We speculate that depression might be a possible risk factor for cefepime-induced encephalopathy. Depression could be related to BBB impairment and cause increased central nervous system concentration of cefepime.14-16 As molecular biological mechanisms in depression, the increase of BBB permeability by VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor)/VEGFR2 (VEGF Receptor 2),15 and the damage of BBB integrity through the loss of tight junction protein claudin 5,16, 17 are reported to occur respectively. These changes contribute to the promotion of peripheral IL-6 passage across BBB,16, 17 speculated to make brain more vulnerable to cefepime.

Concerning depression, is it possible that the antidepressant itself was one of the basic factors that led to the development of antibiotic encephalopathy? In studies in rats, a paper is known to show that high concentrations of antidepressants such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and clomipramine affect the BBB by damaging endothelial cells.18 However, we could find no literatures describing that antidepressants themselves actually affect the BBB in human. Moreover, as for mirtazapine, no prior reports suggesting an effect on the BBB are known.

Furthermore, we also speculate that cancer itself is a possible risk factor for cefepime-induced encephalopathy. Breast cancer cells are known to release microRNA-181c-containing extracellular vesicles, which damage the BBB, leading to brain metastasis eventually.19 Although brain metastasis was not observed in this case, a similar microRNA-related mechanism might be involved with rectal cancer as in breast cancer, leading to BBB vulnerability to cefepime.

In this case, although metronidazole was administered with cefepime, no clinical findings suggested metronidazole-induced encephalopathy. Metronidazole-induced encephalopathy typically presents with peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar dysfunction, visual impairment, vestibulotoxicity, and cochleotoxicity.20 Moreover, 90% of patients with metronidazole-induced encephalopathy show reversible symmetrical hyperintense lesions of the dentate nuclei on brain MRI.9 Besides, liver diseases are considered the most common pre-existing condition,9 and long-lasting sequelae are often reported even after discontinuing metronidazole.21 Since none of these characteristic features were observed in this case, metronidazole was not considered directly related to the encephalopathy.

Notably, delirium regardless of causes, including cefepime-induced encephalopathy, and depression are similar to one another in many aspects, such as lethargy, motionlessness, and loss of energy. This means that if cefepime-induced encephalopathy develops in patients with depression, it is difficult to distinguish their clinical features clearly, resulting in misdiagnosis or delay in proper treatment. The proportion of patients with underlying neurological disease is reported only 10.1% of all patients with cefepime encephalopathy.5 However, we estimate that the previous cefepime-induced encephalopathy cases with underlying neurological diseases, including depression, are limited, partly because of the difficulty in distinguishing the psychiatric symptoms of cefepime-induced encephalopathy from depression and other neurological diseases. We can safely assume that when the diagnosis is difficult, EEG is recommended because a tri-phasic wave pattern or NCSE is often observed in cefepime-induced encephalopathy, even if the psychiatric symptoms are inconclusive.

One limitation of this report is that we could not determine the predominant risk factor between depression and cancer for cefepime-induced encephalopathy. Although there were no clinical symptoms indicating metronidazole-induced encephalopathy, the effect of metronidazole cannot be completely ruled out. Moreover, data on the serum cefepime concentration in this case is lacking, although the cefepime dose was appropriate, and renal function was normal. Besides, the possibility of chemotherapy-induced BBB damage is unclear, although no literature was found on the possibility of BBB damage from the same regimen used in this case.

We speculate that depression and cancer might be occult risk factors for cefepime-induced encephalopathy in terms of BBB dysfunction. Oncologists and liaison psychiatrists should pay enough attention to cefepime-induced encephalopathy when administering cefepime in patients with depression or cancer. Further investigations are warranted to verify this association.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Junji Yamaguchi treated the patient, acquired data, drafted the manuscript, and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patient and the family for their participation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol by an Institutional Review Board: N/A.

Informed consent: The patient and her family provided written informed consent for publication.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All the data supporting this case are available within the report.