Augmented digital human vs. human agents in storytelling marketing: Exploratory electroencephalography and experimental studies

Abstract

As the fourth industrial revolution unfolds and the use of digital humans becomes more commonplace, understanding digital humans' potential to replace real human interaction or enhance it, particularly in storytelling marketing contexts, is becoming evermore important. To promote interaction and increase the entertainment value of technology-enhanced storytelling marketing, brands have begun to explore the use of augmented digital humans as storytelling agents. In this article, we examine the effectiveness of leveraging advanced technologies and delivering messages via digital humans in storytelling advertisements. In Study 1, we investigate the effectiveness of narrative transportation on behavioral responses after exposure to an interactive augmented reality mobile advertisement with a digital human storyteller. In Study 2, we compare how consumers respond to augmented digital human versus real human storytelling advertisements after conducting an exploratory neurophysiological electroencephalography study. The findings show that both types of agents promote narrative transportation when the story fits the product well. Moreover, a digital human perceived as more human-like elicits stronger positive consumer responses, suggesting an effective new approach to storytelling marketing.

1 INTRODUCTION

The fourth industrial revolution is shaping the consumer market as reality-enhancing technologies are becoming part of the “new normal.” This technological shift—particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic—has led many consumers to embrace the virtual environments that firms are increasingly incorporating into consumer marketing strategies. In this new industrial revolution, firms are using advanced technologies such as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), artificial intelligence (AI), machine leaning, and digital humans to enhance consumer experiences. Among these technologies, AR is becoming increasingly popular due to the widespread access to handheld mobile devices. AR provides technology-enhanced immersive consumer experiences by superimposing digital content such as graphics, augmented video, and audio onto the immediate physical environment (Flavián et al., 2019; Rauschnabel, 2021). AR mobile apps have become an easy way to promote consumer engagement (Deng et al., 2019; Hilken et al., 2022; Sung et al., 2022a), as firms develop additional immersive technology marketing initiatives to provide memorable consumer experiences (Flavián et al., 2019; Hilken et al., 2022; Rauschnabel, 2021; Sung, 2021).

These digital technology marketing strategies often combine storytelling with reality-enhancing technology via augmented digital humans. Digital humans are computer graphics with anthropomorphic physical characteristics (Chihara et al., 2017). With digital humans equipped with AR technology (i.e., augmented digital humans), firms can incorporate storytelling into a variety of tasks, such as customer service, brand marketing, and product support. Storytelling is a powerful marketing approach because it effectively holds consumers' attention (van Laer et al., 2014). Through a process called narrative transportation, consumers experience cognitive and affective engagement with the stories they consume across myriad modalities, including movies, books, short commercial videos, video games, and so forth (Dessart, 2018). Through narrative transportation, consumer immersion serves as the primary mechanism of persuasion and leads to consumer attitudes that are aligned with those contained within the narrative (Argo et al., 2008; Escalas, 2007; Green & Brock, 2000).

Storytelling advertisements that promote narrative transportation are called narrative advertisements. These narrative advertisements lead to immersion in the mental process of narrative construction (Busselle & Bilandzic, 2008; Gerrig, 2018). They can be combined with immersive technologies (e.g., AR, digital humans) associated with the fourth industrial revolution to promote consumer experiences and direct and indirect forms of consumer engagement, such as social media sharing intentions and purchase behavior. Thus, digital humans could be effective storytellers because they convey rich visual and auditory information and have the capacity to communicate emotional states (Loveys et al., 2020; Sung et al., 2022b).

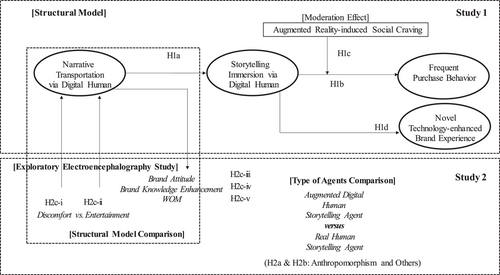

Our studies, as depicted in Figure 1, fill an important research gap by first, showing how digital humans influence consumer responses to storytelling advertisements (Study 1) and second, by comparing the effectiveness of real and digital human storytellers as facilitators of narrative transportation (Study 2). In Study 1, we investigate how technology-driven storytelling advertising through an augmented digital human via an AR mobile app promotes positive consumer experiences by testing a model. In Study 2, we use electroencephalography (EEG) in an exploratory study to measure neurophysiological responses during the narrative transportation process before comparing the effectiveness of real and digital human storytellers as facilitators of narrative transportation in experimental main studies. Findings indicate that an augmented digital human is an effective medium for the storytelling advertisement immersion process, as it leads to positive consumer responses, such as technology-enhanced brand experience and purchase intentions. Findings also show that a digital human perceived as more human-like can be similarly effective to (e.g., elicit positive consumer responses) or even better than an actual human storyteller. Therefore, we argue that digital humans perceived as more human-like have the potential to replace real human storytellers in certain advertisement contexts, depending on factors such as the type of adverting story, product category, brand-story fit, and consumer experience.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Our research draws on theories and concepts from the literature on reality-enhancing technology (Hilken et al., 2022; Rauschnabel, 2021), digital humans (Loveys et al., 2020), and storytelling (Holt & Thompson, 2004), including narrative transportation (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022; Van Laer et al., 2014). AR advertising could be particularly useful for firms that want to increase consumer engagement or promote brand awareness by providing an immersive consumer experience. De Ruyter et al. (2020) argued that the aim of AR advertising, unlike other applications of AR, is to create digital affordances (i.e., perceived action possibilities; Norman, 1988) that stimulate consumer behavior in physical surroundings. According to Norman (1988), affordances in the physical world are bound by the constraints of reality, whereas the digital realm offers limitless potential for reimagining and reshaping the environment. Thus, AR advertising, which has significant digital affordances, aims to enhance consumer engagement and brand awareness, ultimately leading to positive actions, such as purchase behavior and voluntary brand endorsement, by impressed consumers. Other types of AR applications can serve to provide education, training, and convenient access to services to enhance overall marketing effectiveness. In this study, we focus on the use of an augmented digital human storyteller in AR advertising. Recent advances in mobile apps have enabled consumers to engage with AR narratives, such as storytelling advertisement, through their handheld devices.

2.1 Narrative transportation

Narrative transportation has attracted significant interest in marketing literature (Van Laer et al., 2014). Narratives enable factual information to be communicated in a mentally and emotionally stimulating way, which can lead to increased sales in the retail environment (Hughes et al., 2016). Narrative transportation theory suggests that storytelling through media can stimulate immersion in the content of the story, which facilitates temporal “transportation” of the individual into the context of the story (Green & Brock, 2000). For narrative transportation to occur, an individual must use all their mental faculties to interpret the story (Busselle & Bilandzic, 2008). Therefore, if consumers have difficulty understanding a story's meaning, narrative transportation is hindered (Gerrig, 2018). In narrative ad messages, the product-story link is a characteristic of the narrative, and product-story (or brand-story) fit plays an important role in the narrative transportation process (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022).

Storytelling helps organizations communicate their values, strengthen brands, and establish the context for consumer experiences, all of which help create meaning and build customer relationships (Hollenbeck et al., 2008). Storytelling is a tool to trigger audiences' cognitive and emotional processes (Gabriel, 2000), which can lead to immersion, a psychological state in which consumers are fully engrossed in the environment and exclusively fixated on brand interaction (Novak et al., 2000). When consumers experience high immersion, they are more satisfied with a product (Hoffman & Novak, 1996). Furthermore, immersion in the story context is a phenomenological experience of people's engagement with narratives—they “travel” into the story world and are changed by the journey-like experience (Gerrig, 2018). For the purposes of this study, we define storytelling immersion as a mental state in which consumers are fully engaged with and transported into another world while interacting with AR.

In Jung and Im's (2021) study of influencer characteristics, consumers' immersion in a story played a mediating role between characteristics of the influencer (storytelling agent) and product attitudes. Likewise, under a brand-story fit (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022), in our study, storytelling immersion via a reality-enhancing technology (i.e., the storytelling agent) has a positive effect on behavioral intention. A digital human is a new type of interactive agent that can help firms implement storytelling strategies (Sagar et al., 2014). Digital humans are equipped with the capacity for speech recognition and synthesis, as well as emotional expression via visual and auditory information (Loveys et al., 2020). Digital humans are also embodied conversational agents whose appearances and reality perceptions can be enhanced, thereby enabling them to naturally interact with consumers and express emotional states to respond appropriately (Loveys et al., 2020; Sagar et al., 2014). Firms have incorporated augmented digital humans with these characteristics effectively into their marketing strategies to elicit positive consumer responses (Sung et al., 2022b). Thus, we expect the effectiveness of storytelling immersion to be tied to the perceived realism of digital humans, and that narrative transportation could effectively prompt consumer immersion via reality-enhancing technology, given consumers' strong interest in new entertaining technology. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H1a.Narrative transportation via an augmented digital human positively influences storytelling immersion.

2.2 Frequent purchase behavior

Previous findings show that the quality of digital humans in consumer interactions increases purchase intentions (Sung, Bae, et al., 2021). While purchase intentions can be measured as a direct response to a stimulus, the frequency of purchases can provide an additional indicator of brand loyalty and the attractiveness of AR experiences (Raggiotto et al., 2019; Visentin & Scarpi, 2012). Evidence shows that positive technology experiences are associated with repeat use intentions in contexts involving games (Wu et al., 2020), AI (Ashfaq et al., 2020), and VR (Ibrahim & Hidayat-ur-Rehman, 2021). Although consumers generally tend to respond positively to technology (Nikou et al., 2019) or technology-enhanced services (Ashfaq et al., 2020), whether effective marketing via immersive technologies influences consumers' repeat purchase intentions is unclear (Heller et al., 2021; McLean & Wilson, 2019). Thus, purchases could be an important indicator of a product's continued appeal. We argue that a positive AR mobile app storytelling advertisement experience promotes social craving to share the experience with different social groups, which in turn positively influences frequent purchase behavior, depending on the AR advertising marketing context. Furthermore, storytelling immersion generates positive consumer responses (Hoffman & Novak, 1996). Thus:

H1b.Storytelling immersion positively influences frequent purchase behavior.

2.3 AR-induced social craving

Social motivation for using technology (e.g., playing a video game) captures users' desire to form relationships with others (Yee, 2006). Adapting this concept to our context, we define augmented reality-induced social craving as a user's desire to socialize with others by experiencing AR together via interactive mobile apps while consuming a promoted product in response to a technology experience. Because an AR storytelling ad provides an entertaining, immersive experience, consumers may want to share this experience with others. Consequently, consumers may feel inclined to socialize while consuming a promoted product after being exposed to the AR advertisement.

In narrative advertisements, product-story fit is an important element for storytelling immersion, indicating the relatedness of the product to the story or brand (Edson Escalas, 2004). Therefore, we expect narrative advertisements with high brand-story fit that promote narrative transportation and storytelling immersion (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022) to have a positive influence on frequent purchase intentions via AR-induced social craving. Because high immersion leads to positive consumer responses or behavioral intentions (Hoffman & Novak, 1996), the interaction between storytelling immersion via an augmented digital human and AR-induced social craving could strengthen intentions to make frequent purchases. Thus:

H1c.Augmented reality-induced social craving moderates the effect of storytelling immersion on frequent purchase intentions such that the effect is more positive under higher levels of social cravings and less positive under lower levels of social cravings.

2.4 Novel technology-enhanced brand experience

Prior studies have highlighted the added interaction value of reality-enhancing technology marketing that promotes brand engagement or enables consumers to have novel technology-enhanced brand experiences (Flavián et al., 2019; Hilken et al., 2022; Rauschnabel et al., 2021; Sung, 2021; Tom Dieck & Han, 2022). Extending previous reality-enhancing technology studies, we anticipate that immersive storytelling marketing via an augmented digital human in an AR mobile app advertisement increases consumers' novel technology-enhanced brand experiences. This positive influence could be due to the novelty of the AR advertisement for brands.

We build on the notion that reality-enhancing technology enables consumers to have new brand experiences, even with familiar brands. AR experiences are unique and new, providing consumers with entertainment or escapism experiences (Hilken et al., 2022; Tom Dieck & Han, 2022). Scholars have argued that owing to its immersive nature, AR mobile app advertising is redefining consumer brand engagement (Hilken et al., 2022; Javornik, 2016). As the experience through augmentation of digital humans is considered novel in the consumer market, we expect storytelling immersion via an augmented digital human to promote technology-enhanced brand experience as a new, positive consumer experience with brand marketing. Thus:

H1d.Storytelling immersion positively influences novel technology-enhanced brand experience.

2.5 Discomfort and entertainment

We adapted the dimension discomfort (i.e., perceptions of awkwardness and strangeness in situations involving digital vs. real human features; Benitez et al., 2017) from the Robotic Social Attributes Scale (Carpinella et al., 2017) to our study context, as it is the strongest predictor of how robots (i.e., human-featured agents) are evaluated. According to Benitez et al. (2017), individuals respond more favorably to human-like robot agents than to machine-like robots in social roles.

Previous studies have found that a human-like appearance is associated with higher likability of a digital human (Wagner et al., 2019); in particular, participants rated the human-realistic avatar in a VR environment as more trustworthy, had more affinity for it, and preferred it as a virtual agent over a cartoon caricature avatar (Seymour et al., 2021). These findings are consistent with findings regarding positive human–robot interaction, where robots with human-like design cues elicited positive social responses to an artifact (e.g., Eyssel et al., 2010; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). However, the beneficial role of anthropomorphism often depends on the context; for example, previous studies have found that anthropomorphism can sometimes be counterproductive and have a negative impact on consumers' attitudes toward artificial human figures generated by advanced technologies (Akdim et al., 2023; Yam et al., 2021). Other studies have found that technological features that are highly similar to human features are effective (Al-Natour et al., 2011; Qiu & Benbasat, 2009).

In contexts involving storytelling marketing, entertainment value is an important factor. For example, in an advertisement, an endorser's entertainment value positively influences value transfer and purchase intentions (Hung et al., 2011). Thus, a message source with entertainment value should effectively promote favorable brand attitudes and positive responses. In addition, consumers are likely to perceive advertising components that are unusual, uncommon, and different (e.g., storytelling via an augmented digital human agent) as interesting and creative.

The divergence concept is another important element of advertising creativity (Lehnert et al., 2014). Divergence manifests in advertisements through novelty, esthetic representation, newness (including potential discomfort with technology), and difference. The contradiction concept attracts consumer attention because it is unusual (Lehnert et al., 2014), and is in line with Wu et al.'s (2020) study indicating that positive technology experiences positively influence responses. Applied to our study context, an augmented digital human agent exhibiting human-like behavior (or a human agent exhibiting machine-like behavior) in advertising could attract consumer attention because it is unusual. With both divergence and contradiction, when two concepts contradict, people feel pressure to change their evaluations of one of the concepts (Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1955).

In light of these arguments, we propose that higher perceived human-like digital humans evoke more positive consumer responses when a brand/product appears in a storytelling advertisement (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022). Therefore, we hypothesize an interaction effect of the storytelling agent (augmented digital human vs. real human) and perceived human likeness (human-like, somewhat human-like, or machine-like) on consumer responses (i.e., entertainment, narrative transportation, and word of mouth).

H2a.Human and augmented digital human storytelling agents elicit different consumer responses with regard to (i) anthropomorphism, (ii) discomfort, (iii) narrative transportation, and (iv) word of mouth.

H2b.Perceptions of human-like (vs. machine-like) features of a digital human storytelling agent more effectively elicit positive consumer responses, while perceptions of machine-like (vs. human-like) features of a real human storytelling agent more effectively elicit positive consumer responses.

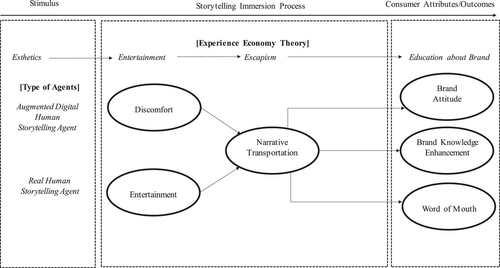

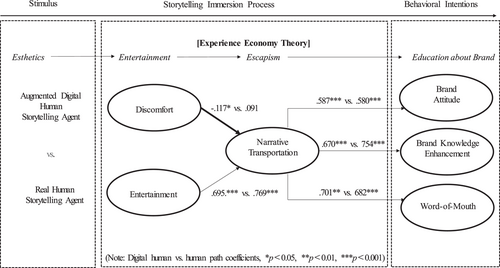

We show our structural path model in the narrative transportation process in Figure 2. To compare the effectiveness of the augmented digital human versus real human storytelling agents in the structural model, we draw on experience economy theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1998; Sung et al., 2022b); and the divergence, contradiction, and narrative transportation concepts (path from discomfort to narrative transportation). Specifically, of the four elements of experience economy theory, we argue that esthetics (i.e., a storyteller's face) influences entertainment value, which triggers escapism (i.e., immersive narrative transportation), potentially leading to education (i.e., brand knowledge) experiences. The two storytelling agents are esthetic elements of the stimuli, with consumer discomfort based on the agent's esthetics (e.g., face, overall design).

For the path from discomfort to narrative transportation, we argue that the perceived level of discomfort associated with the digital human storyteller will influence immersive narrative transportation. This suggests that the more consumers are comfortable with the digital human, the greater is the narrative transportation (positive response) of the storytelling advertisement. By contrast, consumers' responses will be negative when they feel more discomfort with a digital human.

For the path from entertainment to narrative transportation, story enjoyment and narrative transportation are closely related (Gillespie et al., 2016; Green et al., 2004). Prior studies have demonstrated that increased enjoyment (entertainment) leads to higher levels of narrative transportation through increased connections with characters, more imaginable plots, familiarity, attention, and verisimilitude, as well as other relevant factors (Green et al., 2004; Van Laer et al., 2014). Story enjoyment is an aspect of entertainment experiences targeted by reality-enhancing technologies. Thus, entertainment experiences through storytelling advertisements are likely to have a positive effect on consumer responses.

Increased narrative transportation increases positive attitudes toward messages within the narrative (Green & Brock, 2000). As individuals experience narrative transportation, they are more likely to “return” from the narrative setting with attitudes and opinions that are more aligned with the narrative-based themes (Green & Brock, 2000; Green et al., 2004). Given that advertisements are, by definition, messages that include brand information, it is reasonable to assume that increased narrative transportation leads to more favorable consumer responses, such as brand attitudes (Hamby et al., 2018), brand knowledge enhancement (i.e., brand education as the ultimate experience in experience economy theory; Sung et al., 2022b), and increased word of mouth in online communities (Kozinets, 2019). Thus, on the basis of our literature review, we hypothesize the following:

H2c.The type of storytelling agent (augmented digital human vs. real human) affects narrative transportation, which is influenced by antecedent factors, including (i) discomfort (negatively) and (ii) entertainment (positively); in turn, narrative transportation positively influences (iii) brand attitudes, (iv) brand knowledge enhancement, and (v) word of mouth.

In the following we present two studies. In Study 1, we use an augmented digital human via an AR mobile app to investigate how technology-driven storytelling advertising promotes positive consumer experiences, thereby testing H1. In Study 2, we test H2 by comparing the effectiveness of real and digital human storytellers as facilitators of narrative transportation that influence brand attitudes, brand knowledge enhancement, and word of mouth.

3 STUDY 1: STORYTELLING IMMERSION PROCESS

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Data collection

The 19 Crimes wine brand and criminals' stories in the brand's AR advertisement campaign was selected as the stimuli for study 1. The labels on 19 Crimes wine bottles include pictures of real convicts. Consumers who download an AR app on their handheld mobile device and point the app at the wine label can access an AR advertisement displayed on the screen as a noninteractive layer on top of the physical environment captured by the camera. In the advertisement, digital human criminals share their detailed crime stories, which are based on real historical accounts. A marketing research firm (Qualtrics) collected online survey data from 509 consumers (58.5% male; 67.2% between ages 21 and 40 years; Mage = 40 years, SD = 11.81) who downloaded the mobile app properly, correctly answered several filter questions, and indicated that they drank alcoholic beverages, to evaluate the brand advertisement. Respondents who passed the filter questions (e.g., on story content), attention questions, and the marketing research firm's restricted conditions (e.g., robot answer pattern) received monetary compensation after viewing a storytelling advertisement, in which an augmented digital human criminal described the crime that caused him to be banished to Australia as punishment in 19th-century Britain (Appendix 1).

3.1.2 Measures

To measure our constructs, we adapted and modified items from previous studies to fit our study context or created new items based on existing concepts in the literature (see Table 1). Respondents rated all items on 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). To measure constructs associated with the process of storytelling immersion via an augmented digital human, we adapted questionnaire items from prior studies. We also adapted technology-enhanced brand experience via AR on the basis of the concept of newness or unique experience due to characteristics of reality-enhancing technology. In particular, we adapted the concept of the “novel technology-enhanced brand experience via AR advertising” measurement from current literature on Industry 4.0 technologies. After a pretest (N = 122) to ensure that the advertisements were perceived as unique or new, we finalized the questionnaires for Study 1. Furthermore, we developed one moderation item on the basis of the concept of social motivation using technology (Yee, 2006): “I feel a desire to socialize with others while drinking a 19 Crimes beverage as a result of using this AR app to watch an AR 19 Crimes ad.” Table 1 presents the final measurements of Study 1, including the items.

| Final items | Mean (SD) | Factor loadings | rho_A | AVEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrative transportation via augmented digital human (Green & Brock, 2000) | ||||

|

0.788 | |||

|

5.69 | 0.733 | ||

|

(1.04) | 0.866 | 0.865 | 0.651 |

|

0.845 | |||

|

0.795 | |||

| Storytelling immersion via augmented digital human (Barasch et al., 2018; Jessen et al., 2020) | ||||

|

5.90 (1.23) |

1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Novel technology-enhanced brand experience via AR advertising | ||||

|

||||

|

5.99 (0.94) |

0.818 | 0.683 | |

|

0.802 | 0.773 | ||

| Frequent purchase intentions (Raggiotto et al., 2019); Visentin & Scarpi, 2012) | 0.859 | |||

|

5.74 | |||

|

(1.13) | 0.894 | 0.908 | 0.784 |

|

0.894 | |||

|

0.890 0.863 |

|||

| Augmented reality-induced social craving | 5.61 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| I feel a desire to socialize with others while drinking a 19 Crimes beverage as a result of using this AR app to watch an AR 19 Crimes ad. | (1.33) | 1.000 |

- Abbreviations: AR, augmented reality; AVE, average variance extracted.

3.2 Results

The results of the measurement test using SmartPLS show acceptable convergent and discriminant validities (average variance extracted [AVE] and rho_A values) for all constructs. All factor loadings with multiple items are greater than the threshold of 0.50 (between 0.715 and 0.896; p < 0.05) (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), indicating that each item matches the expected latent construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The results indicate convergent validity, as AVE values range from 0.651 to 0.789, exceeding the threshold of 0.50, and rho_A values range from 0.805 to 0.909, exceeding the threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019). The heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) criterion results indicate discriminate validity (Table 2). All values are lower than the threshold of 0.9 in the heterotrait–monotrait, which is acceptable (Henseler et al., 2015). Overall, the results of the discriminant validity tests show acceptable ranges.

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Purchase | ||||||

| 2. Transportation | 0.886 | |||||

| 3. Social craving | 0.850 | 0.780 | ||||

| 4. Storytelling | 0.601 | 0.672 | 0.564 | |||

| 5. Brand experience | 0.718 | 0.728 | 0.630 | 0.525 | ||

| 6. Moderator | 0.542 | 0.519 | 0.506 | 0.440 | 0.384 |

We also checked for common method bias and ruled out multicollinearity, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values are between 1.466 and 2.818, well below the threshold of 5 for common method variance (Kock, 2015). Figure 3 shows the results of the main structural equation modeling. We used the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach with a bootstrapped sample of 5000 cases to estimate path coefficients for the main structural model. As Figure 2 shows, the results indicate that narrative transportation via an augmented digital human (β = 0.632, t = 14.411, p = 0.000, f2 = 0.664) positively influences digital human storytelling immersion, providing support for H1a. The R-square value of digital human storytelling immersion in AR marketing is 0.399, indicating that the narrative transportation via an augmented digital human explains 39.9% of the variance in digital human storytelling immersion.

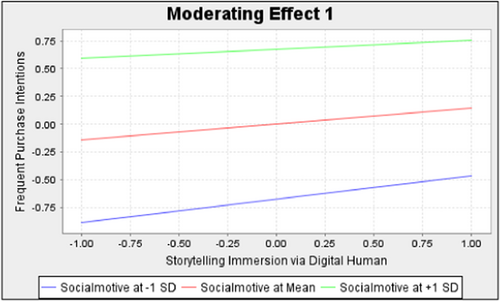

The results also show that digital human storytelling immersion positively influences frequent purchase intentions (β = 0.144, t = 4.202, p = 0.000, R2 = 0.686, f2 = 0.043) and technology-enhanced brand experience (β = 0.475, t = 8.938, p = 0.000, R2 = 0.226, f2 = 0.292), in support of H1b and H1d. In addition, digital human storytelling immersion moderated by AR-induced social craving negatively influences frequent purchase intentions (β = −0.064, t = 3.307, p = 0.001), providing support for H1c. The R-square values for frequent purchase (0.686) and technology-enhanced brand experience (0.226) indicate that digital human storytelling immersion interacting with AR-induced social craving explains 68.6% of the variance in frequent purchase behavior and 22.6% of the variance in technology-enhanced brand experience.

The results for H1c show a negative interaction coefficient (Mittner et al., 2014), indicating that the effect of the combined interaction of storytelling immersion and AR-induced social craving is weaker than the sum of the positive individual effects (social immersion on frequent purchase: β = 0.144; AR-induced social craving on frequent purchase: β = 0.673, p < 0.01). Specifically, the strength of the relationship between storytelling immersion and frequent purchase intentions changes depending on the level of AR-induced social craving, as shown in Figure 4.

In Figure 4, the upper part of the graph indicates that in the high AR-induced social craving condition (+1 SD), storytelling immersion via an augmented digital human strengthens frequent purchase behavior (H1c). The difference between the effects of high and low AR-induced social craving on frequent purchase intentions is larger for low storytelling immersion than for high storytelling immersion. For low storytelling immersion, AR-induced social cravings have a stronger effect on frequent purchase intentions than when storytelling immersion is high.

3.3 Discussion

Study 1's findings reveal a structural storytelling immersion mechanism—a digital human agent prompts brand storytelling immersion through narrative transportation in AR mobile app advertising, leading to positive technology-enhanced brand experiences and frequent purchase behavior moderated by AR-induced social craving. In particular, our findings show increased frequent purchase intentions and technology-enhanced brand experiences due to brand-themed-based storytelling (i.e., the fit between a real historical story and a brand name) via an augmented digital human. Furthermore, our findings reveal that the chosen hedonic product category (alcoholic beverage) fits well with a reality-enhancing technology marketing strategy. Given evidence of storytelling immersion through an augmented digital human involved in an AR mobile app advertisement, in Study 2 we compare the effectiveness of real human and digital human storytellers as facilitators of narrative transportation.

4 STUDY 2: STORYTELLING AGENT EFFECTIVENESS (DIGITAL HUMAN VS. HUMAN)

In Study 2, we shifted our attention to comparing how consumers respond to augmented digital and real human storytelling agents. Understanding the effectiveness of using digital humans versus real humans in marketing strategies is becoming increasingly important to marketing practitioners. Thus, in this study we extended our investigation by comparing the capacity of a digital or a real human storytelling agent to elicit positive consumer responses to storytelling advertising.

4.1 Methods

We designed an experiment to compare reactions to digital and real human storytelling agents in Study 2. We used the same digital human storytelling advertisement as in Study 1 and created a second storytelling video clip for the 19 Crimes wine brand featuring a human whose background story and appearance were similar to the augmented digital human criminal featured in the original storytelling advertisement.

As mentioned previously, product-story fit has an important influence on the narrative transportation process (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022). The food/beverage product category accounts for 76.7% of contemporary mobile ads, and consumers respond positively to new technology that is entertaining or focused on hedonistic products/services (Sung, 2021). When selecting our stimulus, we therefore chose an augmented digital human storytelling advertisement for a hedonic product (wine) in the food/beverage category, with a good fit between the brand (i.e., 19 Crimes) and a crime story (sending prisoners from England to Australia) and reality-enhancing technology with high entertainment value.

4.1.1 Exploratory study: Neurophysiological responses during the narrative transportation process

Following previous communication research that uses neuroscientific tests (Belanche et al., 2017), we collected neurophysiological measurements in an exploratory study before proceeding with the main empirical experimental study. As the results of Study 1 indicate that a digital human can effectively boost narrative transportation, we measured participants' brain activity through EEG to explore their physiological responses during the narrative transportation process (Blocka & Yetman, 2021). In particular, we assessed attention (alpha brain waves), cognitive processing/focus and imagination (beta brain waves; Demon, 2005; Egan, 1992), and working memory (theta brain waves; Gordon et al., 2018) while participants viewed each storytelling video. Attention is a key antecedent of narrative transportation, as consumers who pay more attention to a story are likely to experience a higher level of narrative transportation (Polichak & Gerrig, 2002). According to Pieters and Warlop (1999), increased attention may lead to positive attitudinal and behavioral responses (e.g., word of mouth, purchase intentions). Working memory is an additional precursor of narrative transportation, due to its ability to linguistically process and interpret information (Diamond, 2013) and because it is activated during consumer decision-making and behavior (Tellis & Ambler, 2008).

Prior studies (e.g., Gordon et al., 2018) suggest that EEG data can help identify how stimuli affect brain activity. Because narrative transportation involves attentional focus, working memory, emotional responses, and imagination (Busselle & Bilandzic, 2008; Green et al., 2004), we examined the narrative transportation process in the context of storytelling advertising by monitoring brain waves in real time. According to previous research, stronger frontal brain wave activity indicates attention (Vecchiato et al., 2013).

Following Gordon et al. (2018), we analyzed EEG data to identify how frontal alpha, beta, and theta brain waves respond during the narrative transportation process and possibly differ depending on the type of storytelling agent (digital human vs. real human). Using 19 frontal electrodes, we measured participants' brain waves (N = 20; age: 30–60 years) while being exposed to the narrative of the 19 Crimes AR app in three different conditions (A = digital human, B = real human, C = interactive AR app with digital human; see Appendix 2). Half the participants were exposed to the conditions in different order to account for any ordering effects. However, as condition C involved using the actual AR app to access digital human storytelling content, it was the last task for both groups. Participants viewed a black screen before the first stimulus was shown and during 5-s breaks between conditions to measure brain waves at the baseline and during resting periods to ensure proper data synchronization and analysis. As Appendix 2 shows, participants sat in front of a computer screen while their brain waves were being measured.

The results reveal that both alpha and theta brain wave activity strengthened during the narrative transportation process for all groups. Beta brain wave activity also strengthened for all groups in response to general activation of the brain when exposed to stimuli. In additional analysis, we again followed Gordon et al. (2018) and plotted a frequency analysis as a moving window, varying the time of the window (i.e., 2, 5, and 10 s). While we can measure activity of the alpha, beta and theta waves supporting the narrative transportation process in both digital human and human agents, the brain wave data do not exhibit significantly different patterns among groups. Thus, brain waves measured through EEG are supported during the narrative transportation process, but there are no particular differences in brain wave patterns among the conditions.

4.1.2 Main experimental study (hypotheses tests)

After finding support for initial neurophysiological responses during the narrative transportation process, we conducted the main empirical study to test specific hypotheses on the effectiveness of augmented digital human versus real human storytelling agents. Participants in each condition received instructions and background information (see Figure 5) before viewing the storytelling advertisement matching their condition. First, we conducted a pretest to validate our constructs by collecting data from 46 students at a U.S. business school who were majoring in marketing and management. Second, after making minor changes to the survey format and measurements based on the results and feedback from participants, we conducted the main tests. We recruited 460 master-level participants (evaluated as exhibiting high performance) through Amazon Mechanical Turk who passed the attention check question (Berry et al., 2022). Among the 460 responses, 453 were usable (56.7% male; 58% between ages 24 and 40 years; Mage = 41.5 years, SD = 10.3). We randomly assigned participants to one of two storytelling conditions (augmented digital human vs. real human).

4.1.3 Measurement

We measured all items using 7-point Likert scales. To measure anthropomorphism, we modified one item from Stroessner and Benitez (2019): “How would you evaluate the degree of human likeness of the storyteller in the 19 Crimes advertisement?” (1 = very human-like, 7 = very machine-like). To investigate the effect of the interaction between a storytelling agent (digital human vs. real human) and anthropomorphism on consumer responses, we assigned participants to three groups based on their responses to items about the storyteller's appearance: human-like (i.e., “very human-like” and “human-like”), somewhat human-like, and machine-like (i.e., “somewhat machine-like,” “machine-like,” and “very machine-like”). We excluded neutral responses.1

We also modified items from previous studies to measure consumer responses. To measure the Robotic Social Attributes Scale dimension of discomfort (Carpinella et al., 2017), we asked participants to evaluate the awkwardness and strangeness of the storyteller's appearance in the AR advertisement using modified items from studies involving robots. We used one item on storytelling/narrative immersion (Barasch et al., 2018; Jessen et al., 2020). We made minor revisions based on the pretest to clarify meaning and to ensure consistent reliability among narrative transportation items (e.g., “How much did you feel immersed in the AR advertising crime story (experience)?” (Barasch et al., 2018; Jessen et al., 2020; 1 = not immersed, 7 = highly immersed). Table 3 presents our final measurements and items.

| Construct | Measurement item | Factor loading (digital/real human) | rho_A (digital/real human) | AVE (digital/real human) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand knowledge enhancement (Mehmetoglu & Engen, 2011; Oh et al., 2007; Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2013) | I learned about the 19 Crimes wine brand information/story. | 0.872/0.842 | 0.862/0.830 | 0.757/0.737 |

| The storytelling advertising experience made me more knowledgeable about the brand. | 0.891/0.900 | |||

| The storytelling advertising experience stimulated my curiosity to learn about the promoted product. | 0.847/0.832 | |||

| Brand attitude (MacKenzie et al., 1986; MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989) | Measure of brand attitude by asking participants to evaluate the 19 Crimes wine brand on 7-point scales: 1 = negative, 7 = positive | 0.958/0.929 | 0.972/0.960 | 0.896/0.856 |

| 1 = dislike, 7 = like | 0.950/0.909 | |||

| 1 = bad, 7 = good | 0.947/0.923 | |||

| 1 = unfavorable, 7 = favorable | 0.955/0.936 | |||

| 1 = unpleasant, 7 = pleasant | 0.924/0.928 | |||

| Discomfort (Carpinella et al., 2017) | The human features of the storyteller in the AR advertisement are strange. | 0.954/0.977 | 0.926/1.09 | 0.918/0.913 |

| The human features of the storyteller in the AR advertisement are awkward. | 0.964/0.934 | |||

| Narrative transportation (Green & Brock, 2000) | While I was watching the narrative advertisement via an augmented digital human, I could easily picture the context of the crime story. | 0.904/0.924 | 0.918/0.935 | 0.804/0.837 |

| I could picture the events described in the narrative advertisement via an augmented digital human. | 0.919/0.915 | |||

| I felt an emotional connection with the narrative advertisement via an augmented digital human. | 0.829/0.855 | |||

| I could vividly imagine the crime story scene. | 0.931/0.962 | |||

| Word of mouth (Sung, 2021) | I would like to post on social media about this AR marketing/advertisement experience. | 0.955/0.961 | 0.968/0.970 | 0.911/0.916 |

| I would like to share this AR advertisement experience on my social media. | 0.962/0.964 | |||

| I would recommend this AR advertisement to others on my social media. | 0.960/0.963 | |||

| I would like to tell other people positive things about this AR experience on my social media. | 0.940/0.941 | |||

| Entertainment (Wang et al., 2010; Yussof et al., 2011) | The storytelling experience was entertaining. | 0.967/0.970 | 0.946/0.953 | 0.901/0.910 |

| The storytelling experience was fun. | 0.947/0.955 | |||

| The storytelling experience was interesting. | 0.934/0.935 |

- Abbreviations: AR, augmented reality; AVE, average variance extracted.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Manipulation check and measurement validity

Participants perceived the augmented digital human storyteller (M = 3.65, SD = 1.67) as less human-like than the real human storyteller (M = 2.00, SD = 1.48; p < 0.001).

Table 3 shows the measurement items and acceptable values for convergent and discriminant validities (AVE and rho_A values). All factor loadings with multiple items are greater than 0.7 (p < 0.05), exceeding the cutoff of 0.50 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988), indicating that each construct matches the expected latent construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The results also indicate convergent validity, as AVE values range from 0.712 to 0.924, exceeding the threshold of 0.50, and rho_A values range from 0.852 to 1.189, exceeding the threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019). The heterotrait–monotrait values (<0.783) are below the cutoff value (Henseler et al., 2015), indicating acceptable discriminant validity (see Table 4). For the multicollinearity test, all VIFs values are less than 1.02, below the threshold of 5 for common method variance (Kock, 2015).

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Brand attitude | ||||||

| 2 Brand knowledge enhancement | 0.617 | |||||

| 3 Narrative transportation | 0.581 | 0.733 | ||||

| 4 Word of mouth | 0.519 | 0.610 | 0.741 | |||

| 5 Discomfort | 0.319 | 0.219 | 0.375 | 0.278 | ||

| 6 Entertainment | 0.773 | 0.771 | 0.766 | 0.627 | 0.427 |

4.2.2 Main results

To test H2a that human and augmented digital human storytelling agents elicit different consumer responses with regard to (i) anthropomorphism, (ii) discomfort, (iii) narrative transportation, and (iv) word of mouth, we conducted t-tests to compare responses to the two advertising stimuli. The results show a significant difference in perceived anthropomorphism between the two groups (augmented digital human: M = 3.65, SD = 0.11; human: M = 2.00, SD = 0.099; p < 0.001), with greater human likeness reported by participants who viewed the ad with the human storyteller, in support of H2a(i). For discomfort, the results show a significant difference between the two groups (augmented digital human: M = 4.50, SD = 1.68; human: M = 2.91, SD = 1.81; p < 0.001), with those who viewed the ad with the augmented digital human storytelling agent indicating greater discomfort, supporting H2a(ii). Differences between the two groups are not significant (p > 0.05) for narrative transportation (H2a[iii]) and word of mouth (h2a[iv]).

To test H2b, which predicts interaction effects of the storytelling agent (augmented digital human vs. real human) and perceived anthropomorphism on consumer responses, we conducted a two-way multivariate analysis of variance. The two independent variables are the storytelling agent and anthropomorphism (human-like, somewhat human-like, and machine-like); consumer responses (dependent variables) are (i) entertainment experience, (ii) narrative transportation, (iii) brand attitude, (iv) brand knowledge enhancement, and (v) word of mouth. The results show significant effects of the interaction between storytelling agent and anthropomorphism on the dependent variables (F(10, 866) = 2.45, p = 0.007; Wilks's Λ = 0.946).

The results show support for H2b(i), as the effect of the interaction between an augmented digital human storytelling agent and perceived anthropomorphism (human-like: M = 5.83, SE = 0.18; somewhat human-like: M = 0.5.45, SE = 0.17; machine-like: M = 4.87, SE = 0.16) on entertainment experience is statistically significant (F(2, 434) = 4.959, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.022). Pairwise comparisons show significant differences (p = 0.003), indicating that consumers derive more entertainment value when they perceive an augmented digital human as more human-like than machine-like. Other pairwise comparisons do not indicate statistically significant differences between groups.

In addition, we find a statistically significant effect of the interaction between an augmented digital human storyteller and perceived anthropomorphism (human-like: M = 5.42, SE = 0.17; somewhat human-like: M = 0.4.77, SE = 0.15; machine-like: M = 4.47, SE = 0.14) on narrative transportation (F(2, 434) = 7.180, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.032), in support of H2b(ii). Pairwise comparisons show significant differences (p < 0.05), except between somewhat human-like and machine-like, indicating that storytelling immersion increases when an augmented digital human appears more human-like than machine-like. Other pairwise comparisons do not indicate statistically significant differences between groups.

Moreover, we find a significant effect of the interaction between an augmented digital human storytelling agent and anthropomorphism (human-like: M = 5.31, SE = 0.15; somewhat human-like: M = 5.12, SE = 0.13; machine-like: M = 4.82, SE = 0.12) on brand attitude (F(2, 434) = 4.180, p = 0.016, η2 = 0.019), in support of H2b(iii). Pairwise comparisons show significant differences (p < 0.05), indicating that consumers have more positive brand attitudes when an augmented digital human seems more human-like than machine-like. Other pairwise comparisons do not indicate statistically significant differences between groups.

However, we find no significant effect of the interaction between the storytelling agent and anthropomorphism on brand knowledge enhancement (F(2, 434) = 2.001, p = 0.136, η2 = 0.009). Pairwise comparisons show no significant differences in knowledge enhancement based on perceptions of anthropomorphism in either the group exposed to the augmented digital human storytelling agent or the group exposed to the real human storytelling agent.

Finally, we find a significant effect of the interaction between an augmented digital human storytelling agent and anthropomorphism (human-like: M = 4.18, SE = 0.22; somewhat human-like: M = 3.08, SE = 0.21; machine-like: M = 3.08, SE = 0.21) on word of mouth (F(2, 437) = 8.68, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.038), in support of H2b(v). Pairwise comparisons show significant differences between consumers who perceived the augmented digital human as human-like and somewhat human-like and between consumers who perceived the augmented digital human as human-like and machine-like (p < 0.05), indicating that consumers engage more in word of mouth when an augmented digital human appears more human-like than machine-like. Other pairwise comparisons do not indicate statistically significant differences between groups. Table 5 presents the results of the hypotheses tests for H2a and H2b.

| Hypothesis | Description | Sub-dimensions | Support/no support |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2a | Human and augmented digital human storytelling agents elicit different consumer responses. | (i) Anthropomorphism (ii) Discomfort (iii) Narrative transportation (iv) Word of mouth |

(i) Support (ii) Support (iii) No support (iv) No support |

| H2b | Perceptions of human-like features of a digital human storytelling agent more effectively elicit positive consumer responses, whereas perceptions of machine-like features of a human storytelling agent more effectively elicit positive consumer responses. | (i) Entertainment (ii) Narrative transportation (iii) Brand attitude (iv) Brand knowledge enhancement (v) Word of mouth |

(i) Support (ii) Support (iii) Support (iv) No support (v) Support |

With a bootstrapped sample of 5000 cases, we used multigroup partial least squares structural equation modeling to test H2c, which posits that the storytelling agent (augmented digital human vs. human) affects storytelling immersion via narrative transportation, which is influenced by the antecedent factors of (i) discomfort (negatively) and (ii) entertainment (positively), and that, in turn, narrative transportation positively influences (iii) brand attitude, (iv) brand knowledge enhancement, and (v) word of mouth. Estimated path coefficients for the structural model of the storytelling immersion process appear in Figure 6. The results indicate support for our model for participants exposed to the augmented digital human storytelling agent, as all paths are significant; for those exposed to the human storytelling agent, all paths are significant, except the path between discomfort and narrative transportation (p > 0.05). The results, especially for those exposed to the augmented digital human storytelling agent, indicate that high discomfort associated with perceptions of a digital human as machine-like decreases narrative transportation. This means that an augmented digital human that seems more human-like increases storytelling immersion through narrative transportation. However, because consumers do not feel discomfort when exposed to a real human storytelling agent, the path from discomfort to narrative transportation is not significant for this group (p > 0.05).

Specifically, the results indicate that comfort (discomfort) has a significant, positive (negative) influence on narrative transportation, but only for those exposed to the augmented digital human storytelling agent (βDigitalHuman = –0.117, t = 2.355, p = 0.019 vs. βHuman = –0.091, t = 1.624, p > 0.05), providing support for H2c(i). In addition, the results indicate that entertainment experience positively influences narrative transportation (βDigitalHuman = 0.695, t = 14.657, p = 0.000; βHuman = 0.769, t = 22.490, p = 0.000), providing support for H2c(ii). The results also show that narrative transportation positively influences brand attitude (βDigitalHuman = 0.587, t = 11.350, p = 0.000; βHuman = 0.580, t = 11.538, p = 0.000), brand knowledge enhancement (βDigitalHuman = 0.670, t = 16.593, p = 0.000; βHuman = 0.754, t = 27.127, p = 0.000), and word of mouth (βDigitalHuman = 0.701, t = 22.031, p = 0.000; βHuman = 0.682, t = 18.714, p = 0.000), in support of H2c(iii), H2c(iv), and H2c(v), respectively. The multigroup analysis also shows that the path between discomfort and narrative transportation is significantly different between the two groups (augmented digital human vs. real human), indicating that narrative transportation is stronger when consumers are exposed to an augmented digital human storytelling agent that elicits less discomfort than when they are exposed to a human storyteller (path coefficient difference = −0.208, p = 0.01).

Furthermore, the structural equation model shows significant differences between the two storytelling agent groups in total indirect effects of discomfort on brand attitude (–0.122, p = 0.009), brand knowledge enhancement (–0.147, p = 0.012), and word of mouth (0.144, p = 0.009). Likewise, the structural model shows significant differences between the two storytelling agent groups in the total direct effect of discomfort on narrative transportation (–0.208, p = 0.010) and the three indirect effects mentioned previously.

4.3 Discussion

In an exploratory study, consumers' neurophysiological responses proved that storytelling advertising can support the narrative transportation process, as measured by alpha (attention), beta (cognitive processing, focus, or imagination), and theta (working memory such as interpreting information) brain waves. Study 2 shows that the type of storytelling agent (digital human vs. real human) influences consumer responses to storytelling advertisements.

First, when consumers perceive a digital human as somewhat human-like or human-like, digital human storytelling agents better elicit positive consumer responses (i.e., entertainment, narrative transportation, brand attitudes, and word of mouth; uncanny valley theory, Mori et al., 1970) than perceived machine-like digital humans and also real human agents, in accordance with uncanny valley theory and the concepts of divergence and contradiction.

Second, in the structural narrative transportation process model (multigroup path strength comparison), a digital human demonstrated the potential to be effective in evoking overall positive consumer responses similar to an actual human storyteller. In the particular digital human group, less perceived discomfort felt toward digital humans led to greater narrative transportation, which in turn resulted in positive consumer responses. Thus, we argue that digital humans perceived more human-like can replace real human storytellers in certain advertisement contexts.

5 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Using stimuli from the contemporary mobile advertising market (e.g., beverage category, brand-story fit to prompt immersion), Study 1 indicates that an augmented digital human storytelling agent with a human-like appearance directly and indirectly evokes positive consumer responses (i.e., frequent purchase, technology-enhanced brand experience) to AR mobile app advertisements through narrative transportation.

Study 2 compares how the type of storytelling agent (digital human vs. real human) affects consumer responses (e.g., entertainment, brand attitude, brand knowledge enhancement, word of mouth). As mentioned previously, we divided our testing into two parts: (1) consumer responses to the two agents, in which we found that certain responses (i.e., entertainment, narrative transportation, brand attitudes, and word of mouth) were higher in the group perceiving the digital human as more human-like (H2b), and (2) the narrative transportation process model. This part showed similarly effective overall consumer responses (brand attitude, brand knowledge enhancement, and word of mouth) in both groups (H2c). Notably, a digital human perceived with less discomfort was able to boost narrative transportation.

5.1 Theoretical contributions

Previous studies have shown that immersive marketing and advertising driven by reality-enhancing technologies prompt consumer immersion, leading to positive consumer responses (Flavián et al., 2019; Hilken et al., 2022; Rauschnabel, 2021). Extending the AR literature, in Study 1, we explored storytelling advertising immersion (Beckers et al., 2014) via narrative transportation (Van Laer et al., 2014) in a context of reality-enhancing technologies (i.e., AR mobile app with augmented digital humans). Consistent with previous research, our results show that interactive storytelling advertisements via an augmented digital human effectively promote behavioral intentions.

Our findings regarding the effects of an augmented digital human storytelling agent with perceived human-like features align with previous robot studies (Uncanny Valley Theory; Kätsyri et al., 2017; Mori, 1970), the divergence and contradiction concepts (Lehnert et al., 2014; Mandler, 1982), and previous findings on narrative transportation (Gillespie et al., 2016; Green et al., 2004). Specifically, our findings show that in storytelling advertising, perceived human-like augmented digital human storytelling agents are more effective than perceived machine-like digital humans (H2b) and real human agents at eliciting positive consumer responses (i.e., entertainment, narrative transportation, brand attitudes, and word of mouth). When an augmented digital human exhibits human-like characteristics, recipients elaborate more on the message being conveyed.

In addition, while consensus on the beneficial role of anthropomorphism is lacking, we found that perceived human-like augmented digital human storytelling agents are more effective than perceived machine-like digital humans at eliciting positive consumer responses. We specifically used a digital human stimulus that closely resembled a real human because the story was grounded in actual history—specifically, the transportation of prisoners to Australia. Furthermore, the wine brand 19 Crimes fits well with the crime stories, in line with previous studies indicating that product-story fit plays an important role in the narrative transportation process (Glaser & Reisinger, 2022).

Our theoretical framework of the storytelling immersion process also extends the current understanding of the narrative transportation process (Van Laer et al., 2014) by incorporating economy experience theory (Pine & Gilmore, 1998). Specifically, esthetics (Hamby et al., 2018), referring to the appearance of the storytelling agent, influences the entertainment experience, which is an antecedent of narrative transportation as part of the escapism experience. Then, narrative transportation influences brand knowledge enhancement as part of the education experience. Thus, we extend the theory to four elements (esthetics, entertainment, escapism, and education in order) in our narrative transportation model regarding reality-enhancing technology advertisements (Sung et al., 2022b).

Furthermore, we contribute to the literature on the narrative transportation process by comparing different types of storytelling agents and testing two contradictory antecedent concepts: entertainment and discomfort. Our findings show that an augmented digital human storytelling agent with a human-like appearance elicits significantly stronger positive consumer responses through narrative transportation than a real human storytelling agent. This constitutes an important contribution to the narrative transportation experience process model.

Finally, in an exploratory study, we measured participants' alpha, beta, and theta brain waves via EEG as they interacted with stimuli. Our findings support the narrative transportation process in our storytelling context (Gordon et al., 2018).

5.2 Managerial implications

Our empirical results have important managerial implications, as they can inform the development of effective storytelling marketing strategies that incorporate immersive technologies, such as augmented digital humans. First, Study 1 finds that AR storytelling advertising via an augmented digital human (i.e., a digital human superimposed on a real environment) can be an effective way to promote product consumption in a social setting by amplifying social craving. As a brand ambassador, a digital human can deliver information about a brand such as its history and the functional attributes of products and services. Brand managers who use augmented digital human storytelling agents in mobile app advertisements may generate effective marketing results, such as positive behavioral intentions (frequent purchase intentions, brand knowledge) for hedonic products (e.g., alcoholic beverages) consumed in social settings. Consumers often enjoy watching immersive AR storytelling advertisements together, which results in a social craving to consume the advertised product and supports frequent purchase intentions.

Second, as Study 2 indicates that entertainment is higher in the consumer group perceiving the digital human as more human-like, we argue that attracting consumers' attention using technology storytelling advertisements can be effective in giving consumers memorable or fun experiences in pop-up-style retailing, which is typically used to introduce a new product line, test a new market, or generate awareness of a product. With increasing demand for new technology among young consumers, AR pop-up stores are reshaping physical spaces by offering immersive experiences enriched with entertainment elements to present new products and foster closer relationships with consumers. Furthermore, we recommend that firms consider using augmented digital human storytelling agents with human-like features for hedonic products/services when entertainment is an important aspect of storytelling immersion.

Third, the findings show that entertainment, narrative transportation, and word of mouth are higher in the group perceiving the digital human as more human-like. In addition, the findings indicate that a digital human storyteller that is more human-like in AR advertisements increases narrative transportation, which in turn elicits positive consumer responses (e.g., brand attitudes, brand knowledge enhancement, word of mouth). Furthermore, as Study 1 shows, a digital human via AR storytelling mobile app advertisements positively influences behavioral intentions, as it triggers strong social craving. Thus, introducing more human-like digital storytellers may be an effective way for firms to drive narrative transportation in advertisements, leading to voluntary brand endorsement. After watching a human-like digital agent tell an interesting brand story, customers are likely to share the experience on social media and talk about it with their contacts (word of mouth), which helps increase brand awareness and build a favorable brand image.

5.3 Limitations and future directions

This research has limitations, which may open avenues for future research on the use of digital humans and advanced technologies associated with the fourth industrial revolution (e.g., AR) in storytelling advertisements to increase narrative transportation and promote consumer engagement. First, the stimulus in our study was a storytelling advertisement for a hedonic product (i.e., an alcoholic beverage) with strong brand-story fit, for which entertainment is an important aspect of advertising effectiveness. We found that an augmented digital human storytelling agent was as effective as a real human storytelling agent and that consumer responses to the digital human perceived as human-like were similar to or better than those to a human storytelling agent (Study 2). In the future, researchers could assess consumers' responses to advertisements with augmented digital human versus real human storytelling agents in other product categories (e.g., utilitarian goods, search vs. experiential goods, services) with different narratives, to determine whether the results are consistent. For this purpose, potential covariates such as participants' familiarity with the stimulus brand and whether they regularly consume products in the category should be considered. Researchers could also explore how augmented digital human (vs. human) storytelling agents with different levels of anthropomorphism affect consumer responses to advertisements, informational marketing campaigns, or social marketing for policies.

Second, although we controlled the stimuli such that the digital and real human agents were similar in terms of age, gender, facial expressions, narratives, and clothing, they were not exactly the same (e.g., size of the agent, hairstyle). Thus, future research should better control for potential confounding factors while exploring different levels of anthropomorphism. Storytellers with different levels of anthropomorphism (e.g., animated characters) may also be more appropriate when targeting market segments such as children or when advertising other types of products and services to adults (e.g., education). For example, because many members of Generation Z in their teens engage in many everyday activities in the virtual world, avatars and digital humans are becoming increasingly popular as marketing tools. Further investigation into consumer responses on different platforms with specific market segmentation might guide brands in better maximizing the effectiveness of their technology marketing and storytelling advertising strategies to promote immersive consumer experiences.

Furthermore, it might be fruitful to conduct a longitudinal study to examine the effects of digital versus real human storytelling agents in ads. Such a study would help determine whether the positive effects of a digital storytelling agent are due to novelty, and thus are short-lived, or are sustainable over time. Participants were screened as alcohol drinkers but not wine drinkers. A more detailed screening process can be used in future research that would also consider the impact of familiarity. Finally, future research could test different stimuli and participants, as the effects of a humorous (vs. crime story) technology-enhanced storytelling advertisement and cultures with extended conditions to expand our research.

6 CONCLUSION

Overall, augmented digital human storytellers can help brands provide consumers with engaging brand experiences that elicit positive behavioral responses. Such a strategy should be particularly effective for hedonic products with a high brand-story fit. Furthermore, marketers can use human-like digital human agents in storytelling marketing strategies because they are as effective as human agents across all factors and elicit even stronger positive consumer responses in terms of entertainment, narrative transportation, brand attitudes, and word of mouth. These findings merit further investigation in other conditions and product categories.

Digital humans have the potential to replace real human storytellers in certain advertisement contexts. While one type may not be absolutely more effective than the other, as both have their own strengths and weaknesses depending on factors such as the type of adverting story, advertising type, product category, and consumer experience expectations, we found that certain responses were higher in the group perceiving the digital human as more human-like. Thus, using digital human-like storytellers can be a more cost-effective alternative for brands than hiring expensive celebrities for advertisements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Britt Zeijen helped us prepare for the EEG data collection under supervision in the EEG exploratory study. We greatly appreciate her assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1:

Figure A1

APPENDIX 2:

Figure A2

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1 The results for seven separate groups exhibit a similar pattern.