When less is more: Understanding consumers' responses to minimalist appeals

The authors contribute to this research equally. The order of authorship is based on the alphabetical order of authors' last names.

Abstract

Minimalism, which encourages people to live with fewer possessions, is an emerging theme in marketing communication that often appeals to the sustainable ideal of reducing consumption and waste (e.g., Patagonia's “Buy less” campaign). However, consumers' responses to this marketing approach remain under-researched. We investigate whether consumers' responses to minimalist appeals depend on their socioeconomic status. We find that consumers with lower socioeconomic status report less favorable evaluations of brands that adopt minimalist appeals, because these consumers tend to prefer quantity over quality in daily consumption—a preference that is incongruent with minimalism. This effect is moderated by the considerations of product-usage frequency: even consumers with low socioeconomic status can become more favorable toward minimalist brands if the benefit of minimalism, namely the increased usage of each product, is salient.

The most environmentally sustainable jacket is the one that's already in your closet…—Lisa Williams (Chief Product Officer, Patagonia)

Minimalism, a value revolving around the reduction of material possessions and consumption, is an emerging lifestyle and consumer movement. Consumer and academic interest in this concept is growing, especially since the Great Recession (Alexander & Ussher, 2012; Rodriguez, 2018). Consumers may adopt minimalist practices as an identity project (Mathras & Hayes, 2019), a deliberate form of economic behavior (Hulme, 2019; Summers, 2022), a status-signaling practice (Khamis, 2019), or a means of constructing a new human–ecology relationship (Meissner, 2019). While minimalism seems to contradict the presumed objective of marketing, it is increasingly incorporated into branding and marketing strategies. For example, minimalism is central to the philosophy of global brands (e.g., MUJI's emphasis on “simple, minimal, and high quality” products), as well as their coporate social responsibiltiy initiatives (e.g., Finisterre's encouraging consumers to repair rather than replace) and advertising (e.g., Patagonia's “Don't buy this jacket” campaign). This trend raises the question of how consumers respond to brands that incorporate minimalism into their branding and marketing.

The literature on minimalism has focused on how and why individuals adopt minimalist practices and the impact of these practices at the macrosocietal or individual level. Limited research has studied minimalism in the context of marketing communication, calling for systematic reviews of how minimalism is represented in advertising (Margariti et al., 2017) and empirical investigations of the effectiveness of this marking approach. In the present research, we examine whether and when minimalism might be an effective appeal in marketing communication, focusing on the role of consumers' socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is a commonly used segmentation variable that has practical implications for marketers. By shedding light on its role in evaluations of minimalist brands, we also answer researchers' call to better understand the relationship between socioeconomic status and minimalism (Wilson & Bellezza, 2022).

1 MINIMALISM IN MARKETING

Minimalism has been defined in various ways. Some define it as a fine taste that is expressed through simple design, mindful duration, and sparse esthetics in, for example, architecture, fashion, and interior décor (Wilson & Bellezza, 2022). Others construe it as merely a marketing gimmick to increase sales (Meissner, 2019). Minimalism can be practiced involuntarily, as a by-product of financial deprivation (Leipämaa-Leskinen et al., 2016; Pangarkar et al., 2021), or voluntarily, as a status symbol (Eckhardt & Bardhi, 2020) and an expression of autonomy, self-awareness, and taste (Khamis, 2019).

Across these various definitions of minimalism and its motivations, a recurring theme is the reduction of consumption and possessions. This may explain why minimalism has been associated with environmental and ecological justice, as a philosophy to address the unsustainable, precarious capitalist system and a solution to address issues such as consumption waste (García-de-Frutos et al., 2018; Iyer & Muncy 2009; Martin-Woodhead, 2022; Meissner, 2019). Indeed, environmental concerns drive individuals to consciously reduce their consumption for overall societal benefit (Iyer & Muncy 2009). Informed by this approach, we focus on minimalism as a voluntary behavior in which individuals deliberately limit their material consumption and possessions to achieve desirable outcomes. This is consistent with the “anti-consumption” category in the typology of minimalism (Pangarkar et al., 2021) and the “fewer possessions” facet of consumer minimalism (Wilson & Bellezza, 2022). It also echoes the argument that minimalism reflects a paradigm shift in consumer behavior that values the principle of sustainability (Kang et al., 2021).

The growing influence of minimalism on branding and marketing communication (e.g., advertising, brand statements) is presumably driven by minimalism's association with environmental sustainability (Druică et al., 2023; Kang et al., 2021), a value that many brands seek to reflect. This is particularly true in the fashion industry, which is notoriously known for its environmental harm (Pal & Gander, 2018). Without radical intervention, by 2050 the global textile industry could account for one quarter of all carbon emissions (August 9, 2018, The Guardian), incurring enormous environmental costs (Pal & Gander, 2018). Accordingly, brands such as Patagonia have voiced concerns about the industry's environmental impact, advocating a more minimalist and sustainable consumption style in their advertisements and brand statements. The fashion designer Vivienne Westwood urged consumers to “buy less, choose well, make it last” (Westwood, 2022). How do consumers react to fashion brands that incorporate minimalism into their marketing communications (e.g., advertising)? We conjecture that consumers' socioeconomic status plays a role.

2 SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND MINIMALIST APPEAL

Socioeconomic status influences consumption decisions (Shavitt et al., 2016), including decisions on sustainable consumption (Yan et al., 2021) and fashion consumption (Simmel, 1957). Kim et al. (2022) found that consumers with a low (vs. high) childhood socioeconomic status reported more favorable evaluations of sustainable luxury brands because they valued communal cooperation. While one might assume that the same effect applies to minimalist brands, research suggests otherwise. For example, based on qualitative evidence, Dopierała (2017) suggested that the “quasi antimaterialist” nature of minimalism renders it favorable to those with an established material life (i.e., middle- or high-socioeconomic status individuals; see also Wilson and Bellezza [2022]). Informed by prior research, we propose that consumers with lower socioeconomic status show less favorable evaluations of minimalist brands. Furthermore, we suggest that this effect is driven by consumers' quality–quantity preference in consumption.

Consumers often make quality–quantity tradeoffs in consumption decisions, especially for product categories related to household goods, food, and apparel (Liu & Baskin, 2021). Preferences regarding this tradeoff are influenced by various factors (Liu & Baskin, 2021; Sun et al., 2021), including consumers' socioeconomic status (Baumann et al., 2019; Cheon & Hong, 2017). In food consumption, higher socioeconomic status consumers exhibit a preference for quality over quantity, whereas the opposite is true for lower socioeconomic status consumers, who favor filling and economical foods (Deeming, 2014). Due to their experiences of resource constraints, consumers with lower socioeconomic status more highly value the consumption of food in large quantities (Baumann et al., 2019), calorific food (Cheon & Hong, 2017), and food in nonessential categories (e.g., potato chips; Vinkeles Melchers et al., 2009), options that imply poorer nutritional quality (Rankin et al., 1998). Beyond food consumption, research finds that low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers spend larger proportions of their income on products with high signaling value, such as fashion products, as a compensatory strategy (Jaikumar & Sarin, 2015; Sivanathan & Pettit, 2010). They also derive greater happiness from accumulating material possessions (Lee et al., 2018). In contrast, higher socioeconomic status consumers value material consumption to a lesser extent (Weinberger et al., 2017) and stress quality in fashion consumption to create status boundaries (Chen & Nelson, 2020). Taken together, the above research suggests that consumers with lower (vs. higher) socioeconomic status are likely to value consumption quantity over quality.

Importantly, minimalism as a value pertains to the reduction of consumption quantity. Indeed, consumers self-identifying as minimalist report preferring quality over quantity in purchases (Wilson & Bellezza, 2022). This preference associated with minimalism is incongruent with the quantity-over-quality preference associated with low socioeconomic status consumers. We thus predict that low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers, who value quantity over quality in consumption, will be less attracted to brands that emphasize minimalism (i.e., minimalist brands), despite those brands' positive association with sustainability. This prediction is formally stated as follows:

H1.Consumers with low (vs. high) socioeconomic status have less favorable evaluations of brands that adopt minimalist appeals.

H2.The effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands is driven by the preference for consumption quantity over quality.

The predicted effects yield interesting implications. Consumers with lower socioeconomic status account for less environmental harm, due to their lower consumption levels (Ghosh et al., 2020; Oswald et al., 2020). However, we theorize that lower socioeconomic status consumers are less attracted to minimalism brands that encourage consumers to minimize environmental harm through reducing consumption. We, therefore, test the boundary of the proposed effects to identify when minimalist brands could appeal to consumers with lower socioeconomic status. As consumers' ideologies are associated with their choices of and attitudes toward brands (Schmitt et al., 2022), understanding when consumers support minimalist brands may have downstream implications for promoting a more minimalist and sustainable consumption style, a possibility we revisit in Section 10.

3 MODERATOR: QUANTITATIVE CONSIDERATIONS OF PRODUCT USAGE

We identify the boundary of our proposed effect by testing moderators. If the effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands is indeed driven by the preference for quantity versus quality, this effect may be mitigated when other quantitative benefits of minimalism are salient. Inherent to minimalist consumption—buying and owning fewer products—is the idea that consumers will use each owned product for a greater number of times, that is, more frequent and durable usage. Frequency and durability are quantitative aspects of a product's usage that are often neglected by consumers. However, making them salient has been evidenced to influence consumption decisions (Mittelman et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021), such as decisions regarding the consumption of a single luxury good (quality) versus multiple nonluxury goods (quantity; Sun et al., 2021). Informed by these findings, we suggest that prompting quantitative considerations of product usage may moderate our effect.

Specifically, when evaluating a minimalist brand, consumers who tend to consider quantitative aspects of product usage may interpret the brand's stated value of “buying less” as “using a particular product more frequently.” As a corollary, even those who value quantity may be attracted to minimalist brands when they recognize the quantitative benefit of minimalism, namely the increased number of times the product will be used. Relatedly, consumers facing financial constraints are more concerned about deriving lasting utility from their purchases (Tully et al., 2015). Thus, low socioeconomic status individuals may find minimalism appealing when the benefit of deriving greater utility from each product is salient. Accordingly, quantitative considerations of product usage, such as considerations of usage frequency, should moderate the effect of socioeconomic status on consumers' evaluations of minimalist brands. When product-usage frequency is salient, even consumers with low socioeconomic status may be attracted to minimalist brands. This prediction has important strategic implications for marketers: promoting minimalism with an emphasis on product-usage frequency could induce favorable evaluations of minimalist brands among consumers with lower socioeconomic status. Interestingly, this practice has not been widely adopted by minimalist brands. We state our hypotheses formally as follows:

H3.The effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands is moderated by consumers' quantitative considerations of product usage.

H4.Low socioeconomic status consumers become more attracted to minimalist brands when the link between minimalism and increased usage frequency is made salient.

4 OVERVIEW OF STUDIES

We tested our hypotheses in five studies, focusing on minimalist fashion brands. Study 1 showed that consumers' socioeconomic status predicted their preference for a minimalist brand (Patagonia) over a nonminimalist brand (The North Face) in an incentive-compatible choice decision (H1). Studies 2 and 3 experimentally manipulated socioeconomic status. Study 2 revealed that consumers with low (vs. middle or high) socioeconomic status evaluated a fictitious minimalist brand less favorably (H1). Study 3 found that this effect was driven by the stronger preference for quantity over quality associated with low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers (H2). Studies 4 and 5 sampled participants based on their socioeconomic status according to the categorization of the World Economic Forum (Koop, 2022). Study 4 found a moderating effect of usage-frequency considerations on the evaluations of a minimalist brand (H3). Those who tended to consider product-usage frequency showed more favorable evaluations of the minimalist brand, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Study 5 targeted consumers with low socioeconomic status and found that advertising featuring product-usage frequency increased the appeal of a minimalist brand among these consumers (H4).

The data collection procedures were approved by the ethics committees of both authors' affiliated institutions (ETH2122-0899; 40098). Participants provided written consent before participating. We included data from all participants in our analyses. Key measures and stimuli are reported in Supporting Information: Appendix S1.

5 STUDY 1: INCENTIVE-COMPATIBLE BRAND CHOICE

Study 1 investigated the relationship between consumers' socioeconomic status and evaluations of a minimalist brand (H1). We measured brand preference in a realistic, incentive-compatible choice paradigm, namely the choice of a lottery prize. We expected socioeconomic status to correlate with a preference for a minimalist brand (Patagonia) over its nonminimalist competitor (The North Face).

5.1 Method

Participants (N = 200, Prolific; 57.5% female; Mage = 39.46, SDage = 13.74; 11% United States, 89% United Kingdom) completed a survey about Patagonia and The North Face. These two brands were chosen because they are close competitors (Hendelmann 2022), but Patagonia emphasizes minimalism while The North Face does not. Participants viewed each brand's logo and excerpts from their mission statements in counterbalanced order. Patagonia's mission statement includes “Our values reflect … the minimalist style” (Patagonia, 2023), whereas The North Face's includes “Provide the best gear for our athletes and the modern day explorer” (The North Face, 2023), without mentioning minimalism (Supporting Information: Appendix S1).

Participants reported the extent to which they perceived each brand as minimalist (“[brand name] endorses a minimalist value”) and their evaluations of each brand (“I like [brand name]”; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much). They also learned that they would enter a lottery to win a US$30 voucher from one of the two brands, and they indicated their choice between the two (Supporting Information: Appendix S1). This choice measure served as a realistic and incentive-compatible dependent variable.

Participants then reported their household income, education level, and parents' education levels. As income and education level are common indicators of socioeconomic status, we computed a socioeconomic status index by standardizing participants' income and education levels, respectively, and computing their average (Dinsa et al., 2012). We also repeated our analyses using a measure that included participants' parental education levels (Kraus & Tan 2015), and found similar results (Supporting Information: Appendix S2). Participants also reported their age and gender.

5.2 Results and discussion

5.2.1 Stimulus validation

A repeated-measures analysis on perceived minimalism showed that Patagonia was perceived as more minimalist than The North Face (MPatagonia = 4.98, SDPatagonia = 1.58, MNorthFace = 3.84, SDNorthFace = 1.45, F(1, 199) = 70.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.26), validating our choice of stimuli.

5.2.2 Evaluation

Correlation analyses showed that participants' socioeconomic status positively correlated with their liking of Patagonia (r = 0.21, p = 0.003), but not with their liking of The North Face (r = 0.09, p = 0.19). Additional regressions including age and gender as covariates yielded similar results (on Patagonia: b = 0.37, SE = 0.13, t(196) = 2.80, p = 0.006, R2 = 0.06; on The North Face: b = 0.15, SE = 0.13, t(196) = 1.21, p = 0.23, R2 = 0.04). Moreover, the effect of socioeconomic status on the liking of Patagonia held (b = 0.31, SE = 0.12, t(197) = 2.64, p = 0.009) even when controlling for the liking of The North Face (b = 0.45, SE = 0.07, t(197) = 6.94, p < 0.001). This implied that the effect of socioeconomic status on the liking of Patagonia could not be explained merely by consumers' general liking of outdoor-apparel brands.

5.2.3 Brand choice

A binary logistic regression on brand choice for the lottery (1 = Patagonia, 0 = The North Face) yielded a significant positive effect of socioeconomic status (b = 0.40, SE = 0.19, Wald χ2 = 4.61, p = 0.03, odds ratio = 1.49). Participants with lower socioeconomic status were less likely to choose Patagonia over The North Face, supporting H1. This effect held after controlling for age and gender (b = 0.43, SE = 0.19, Wald χ2 = 5.12, p = 0.02, odds ratio = 1.54), attesting to the robustness of the effect. Moreover, a parallel mediation analysis (PROCESS Model 4, 5000 bootstrapped samples) found that liking of Patagonia (95% confidence interval [CI] = [0.174, 1.060]), but not liking of The North Face (95% CI = [−0.725, 1.649]), mediated the effect of socioeconomic status on brand choice. Thus, higher socioeconomic status consumers liked the minimalist brand (Patagonia) more and, in turn, chose it over its non-minimalist competitor (The North Face).1

In brief, using real competing brands that differ in perceived minimalism and an incentive-compatible choice paradigm, our findings supported H1 and demonstrated the ecological validity. In Studies 2–3, described below, we experimentally manipulated socioeconomic status to establish a causal relationship between socioeconomic status and evaluations of minimalist brands.

6 STUDY 2: MANIPULATING SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS

The key objective of this study was to establish a causal relationship between socioeconomic status and evaluations of minimalist brands (H1). We thus manipulated subjective socioeconomic status (high, middle, and low). We also aimed to demonstrate the generalizability of our effect beyond the Patagonia brand and rule out alternative explanations.

6.1 Method

Participants (N = 302, Prolific UK; 68.5% female, Mage = 41.42, SDage = 31.88) completed a three-condition (socioeconomic status: high, middle, and low) between-subjects study. To manipulate subjective socioeconomic status, participants viewed an image of a ladder representing their society, in which a higher position on the ladder indicated higher levels of education, income, and job status. Participants imagined themselves at the top (n = 95), in the middle (n = 104), or at the bottom (n = 103) of the ladder, depending on their randomly assigned conditions, and described how they would look and behave in that social position. They then completed manipulation checks by indicating their income, education, and job status (1 = lowest, 10 = highest; averaged into a socioeconomic status manipulation check index, α = 0.96), and their social class (1 = lower class, 5 = upper class) in the described scenario (Yan et al., 2021).

Next, participants read the brand story of a minimalist brand with a core value of “less is more” (Supporting Information: Appendix S1). To measure brand evaluation, participants reported their attitudes toward the brand (“To what extent do you like this brand?”) and perceived brand quality (“To what extent do you think this brand is of high quality?”; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; adapted from Kim et al., 2022). They also rated the extent to which the brand valued quality over quantity, to test and rule out the possibility that consumers with low- versus high-socioeconomic status form different associations with a minimalist brand owing to the brand's quality–quantity values (rather than differences in consumers' quality–quantity preference, as hypothesized). Finally, participants reported demographic information.

6.2 Results

6.2.1 Manipulation check

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) showed a significant main effect of our manipulation on the socioeconomic status index (F(2, 299) = 195.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57; Mlow = 2.84, SDlow = 2.34; Mmiddle = 5.93, SDmiddle = 1.04; Mhigh = 8.17, SDhigh = 2.11; all contrasts p < 0.001) and the social class measure (F(2, 299) = 170.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.53; Mlow = 1.50, SDlow = 0.85; Mmiddle = 2.65, SDmiddle = 0.65; Mhigh = 3.91, SDhigh = 1.19; all contrasts p < 0.001). The manipulation was successful.

6.2.2 Brand evaluations

An ANOVA of brand attitude showed a significant main effect of socioeconomic status (F(2, 299) = 7.27, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05). Participants in the low-status condition (M = 4.51, SD = 1.28) liked the brand less than did those in the high- (M = 5.19, SD = 1.36, p < 0.001) and middle- (M = 4.90, SD = 1.19, p = 0.03) status conditions (the latter two conditions p = 0.12). A second ANOVA of perceived brand quality yielded consistent results (F(2, 299) = 8.21, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05; Mlow = 4.53, SDlow = 1.34 vs. Mmiddle = 5.08, SDmiddle = 1.11, p = 0.003; versus Mhigh = 5.23, SDhigh = 1.39, p < 0.001; the latter two conditions p = 0.40).

6.2.3 Alternative explanation

An ANOVA of perceptions of the brand's valuation of quality over quantity found no effect (F(2, 299) = 0.84, p = 0.43, ηp2 = 0.006; Mlow = 4.71, SDlow = 1.79, versus Mmiddle = 4.39, SDmiddle = 1.96, versus Mhigh = 4.68, SDhigh = 2.05, all contrasts p > 0.10). Thus, the observed effects on brand evaluations could not be explained by socioeconomic status affecting the participants' association between a minimalist brand and its quality–quantity value.

6.3 Discussion

We replicated the effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands (H1) using an experimental design and thus established a causal relationship. Using three conditions, we found that the effect of socioeconomic status was mainly driven by consumers with low socioeconomic status being less favorable toward minimalist brands. This nuanced insight may help brands better segment and target consumers.

Socioeconomic status did not affect perceptions of whether a minimalist brand values quality over quantity. This speaks against the possibility that low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic-status consumers dislike minimalist brands because they fail to associate minimalist brands with a quality-over-quantity value. In the next study, we tested our proposed underlying mechanism, differences in quality–quantity consumption preferences.

7 STUDY 3: TESTING MEDIATOR

The key objective of this study was to test whether consumption quality–quantity preference mediated the effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands (H2). We further ruled out alternative mechanisms.

7.1 Method

Participants (N = 220, Prolific UK; 64.5% female, Mage = 38.63, SDage = 12.98) completed a two-condition (socioeconomic status: high, low) between-subjects study. Because the middle- and high-status conditions yielded similar effects in Study 2, we manipulated only the low- and high-status conditions here, using the same manipulation procedure as in Study 2.

Following the socioeconomic status manipulation, we administered a consumption quality–quantity preference measure adapted from Sun et al. (2021). Participants were asked to choose between buying one high-end sweater and buying four mid-range sweaters (1 = definitely prefer one high-end sweater; 6 = definitely prefer four mid-range sweaters). Then, they read the same minimalist brand story as in Study 2. They reported their attitude (“How much do you like this brand?”) and purchase intention (“How likely are you to purchase from this brand?,” 1 = not at all, 7 = very much) toward the brand. For expositional ease, we averaged these two items to create a brand evaluation index (α = 0.93), following prior research (Leclerc & Little, 1997; Spears & Singh, 2004), but we reported separate analyses for each item in Supporting Information: Appendix S3.

We also tested the possibility that our effect was driven by process disfluency, that is, low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers finding it more difficult to process the minimalist brand's appeals, reducing persuasion effectiveness (Lee & Aaker, 2004). Participants reported the ease of comprehending the brand story (1 = difficult to understand, 7 = easy to understand; α = 0.92) and perceived conflict in evaluating the brand (1 = not at all conflicted, 7 = extremely conflicted). Finally, they reported demographic information.

7.2 Results and discussion

7.2.1 Manipulation check

Our manipulation was successful (socioeconomic status index: Mlow = 2.25, SDlow = 1.72, Mhigh = 8.88, SDhigh = 1.46, F(1, 218) = 953.58, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.81; social class: Mlow = 1.24, SDlow = 0.05, Mhigh = 4.25, SDhigh = 0.99, F(1, 218) = 761.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78).

7.2.2 Brand evaluations

An ANOVA of brand evaluation showed that participants in the low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status condition reported less favorable evaluations (Mlow = 4.49, SDlow = 1.63, Mhigh = 4.87, SDhigh = 1.34, F(1, 218) = 3.76, p = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.02). This result supported H1 and replicated the findings of Study 2.

7.2.3 Quality–quantity preference

An ANOVA of quality–quantity preference showed that those in the low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status condition expressed a stronger preference for consumption quantity over quality (Mlow = 5.09, SDlow = 1.26, Mhigh = 4.22, SDhigh = 1.63, F(1, 218) = 19.37, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08). Moreover, a mediation analysis using quality–quantity preference as the mediator, socioeconomic status manipulation as the independent variable, and brand evaluations as the dependent variable yielded a significant mediating effect (5000 bootstrapped samples, 95% CI = [0.017, 0.169]), supporting H2.

7.2.4 Alternative explanation

Separate ANOVAs showed that the two conditions did not differ in comprehension ease (Mlow = 5.63, SDlow = 1.24, Mhigh = 5.67, SDhigh = 1.40, F(1, 218) = 0.03, p = 0.86, ηp2 < 0.001) or decision conflict (Mlow = 2.82, SDlow = 1.52, Mhigh = 2.85, SDhigh = 1.56, F(1, 218) = 0.02, p = 0.88, ηp2 < 0.001), ruling out process fluency as an alternative explanation.

7.3 Discussion

This study identified quality–quantity preference as a mediator of the effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of minimalist brands. That is, consumers with low (vs. high) socioeconomic status have a stronger preference for consumption quantity over quality—a preference that is inconsistent with minimalism. This leads them to evaluate a minimalist brand less favorably. In the next study, we tested the potential boundary of our effect.

8 STUDY 4: TESTING MODERATOR

This study had three objectives. First, we tested considerations of product-usage frequency as a potential moderator (H3). Second, we addressed price perceptions and considerations as alternative explanations. Third, we operationalized socioeconomic status by sampling two groups of participants who were considered “lower class” or “upper class” based on the World Economic Forum categorization (Koop, 2022). This sampling approach allowed us to replicate our effect using an objective and ecologically valid operationalization of socioeconomic status that was external to the influence of our study procedures. For the evaluation of minimalist brands, we again used Patagonia as our stimulus (having been pretested to be perceived as minimalist in Study 1).

8.1 Method

Participants (N = 397, Connect US; 49.5% female, Mage = 42.60, SDage = 12.57) completed a two-condition (socioeconomic status: high, low) by usage-frequency consideration (measured) between-subjects study. The World Economic Forum defines lower-class (upper-class) Americans as those whose household incomes fall below US$52,000 (above US$156,000) (Koop, 2022). Following this categorization, we recruited participants whose household incomes were below $50,000 (n = 197) and above $150,000 (n = 200) as proxies for consumers with low- versus high-socioeconomic status, respectively. The participants' household incomes were measured and used by the online survey platform Connect as a screening criterion before the study procedure.

Participants read a paragraph describing Patagonia as a “minimalist outdoor apparel brand” and viewed three real Patagonia advertisements (Supporting Information: Appendix S1). As in Study 3, we measured liking of the brand (“how much do you like this brand, Patagonia?,” 7-point scale). However, unlike in Study 3, where we used a fictitious brand and hence measured purchase intention, here we measured participants' actual purchase experience with Patagonia (“Have you purchased from Patagonia before?,” 1 = yes, 0 = no). Acknowledging that this measure could reflect (and be influenced by) factors other than brand evaluations, we included it in our exploratory analyses, because it provided a more objective measure of purchase behavior.

To rule out potential confounders that might be alternative explanations, we asked participants to what extent they perceived Patagonia as minimalist, sustainable, and expensive.2 Participants then completed measures of demographic information; a social class sampling check (“Where would you place yourself on this ladder?,” 10-point scale, higher numbers indicate higher status; Adler et al., 2000); and items on individual differences in the extent to which they considered different factors in consumption decision-making. Our key interest was product-usage frequency consideration (how much do you make purchase decision of a product based on… the frequency in which I could use a product, 1 = not at all, 7 = very much), which served as our moderator. We also included price consideration to rule it out as an alternative explanation.

8.2 Results

8.2.1 Sampling check

Participants from the lower- (vs. upper-) class group reported lower social status (10-point scale, Mlower = 3.69, SDlower = 1.41, Mupper = 6.65, SDupper = 1.36, F(1, 395) = 453.25, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.53). Thus, our sampling strategy was successful, and we compared the two social-class groups as our independent variable.

8.2.2 Brand evaluations

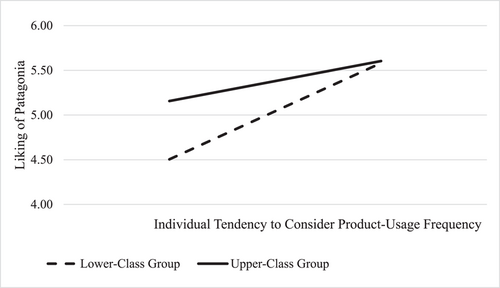

We regressed brand evaluations on social class (−1 = lower class, 1 = upper class), usage-frequency considerations (standardized), and their interaction. We found a main effect of social class (b = 0.17, SE = 0.07, t(393) = 2.39, p = 0.03), supporting H1. We also found a main effect of usage-frequency considerations (b = 0.38, SE = 0.07, t(393) = 5.35, p < 0.001). Critically, we found an interaction effect of social class and usage-frequency considerations (b = −0.16, SE = 0.07, t(393) = −2.21, p = 0.03; Figure 1). Supporting H3, spotlight effect analyses showed that social class positively predicted brand evaluations among those who tended not to consider usage frequency (−1 SD: b = 0.33, SE = 0.10, t(393) = 3.26, p = 0.001), but the effect was mitigated among those who tended to consider usage frequency (+1 SD: b = 0.01, SE = 0.10, t(393) = 0.11, p = 0.91). Slope effect analyses showed that considerations of product-usage frequency had a greater effect for the lower-class participants (b = 0.54, SE = 0.09, t(393) = 5.79, p < 0.001) than for the upper-class participants (b = 0.22, SE = 0.11, t(393) = 2.07, p = 0.04).

8.2.3 Purchase experience

A χ2 analysis revealed that a smaller proportion of participants in the lower- (vs. upper-) class group had purchased from Patagonia (16.8% vs. 47.5%, χ2 = 42.95, p < 0.001). Moreover, we regressed purchase on social class, usage-frequency considerations, and their interaction. As above, we found an interaction effect (b = −0.33, SE = 0.15, z = −2.26, p = 0.02) and a main effect of social class (b = 0.81, SE = 0.13, z = 6.30, p < 0.001). Social class had a smaller effect on purchasing from Patagonia among those who tended to consider usage frequency (+1 SD: b = 0.48, SE = 0.16, z = 2.89, p = 0.004), compared with those who tended not to consider usage frequency (−1 SD: b = 1.14, SE = 0.22, z = 5.16, p < 0.001).

8.2.4 Price

The two social-class groups did not differ in their perceptions of Patagonia being expensive (Mlower = 5.67, SDlower = 1.06, Mupper = 5.66, SDupper = 1.01, F(1, 395) = 0.01, p = 0.93, ηp2 < 0.001). This ruled out the notion that consumers with lower socioeconomic status dislike minimalist brands because they perceive them as pricier. Unsurprisingly, the lower- (vs. upper-) class group reported a greater tendency to consider price in their purchase decision-making (Mlower = 6.31, SDlower = 0.89, Mupper = 5.87, SDupper = 1.12, F(1, 395) = 19.73, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05). However, keeping price considerations as a covariate (b = 0.003, SE = 0.08, t(392) = 0.04, p = 0.97), the observed effects on brand evaluations remained (interaction: b = −0.16, SE = 0.07, t(392) = −2.21, p = 0.03; social-class main effect: b = 0.17, SE = 0.07, t(392) = 2.33, p = 0.02; usage-frequency considerations main effect: b = 0.38, SE = 0.08, t(392) = 4.97, p < 0.001).

8.2.5 Other potential confounders

The two social-class groups also did not differ in their perceptions of the brand being minimalist (Mlower = 5.89, SDlower = 1.03, Mupper = 5.83, SDupper = 1.12, F(1, 394) = 0.37,3 p = 0.56) or sustainable (Mlower = 5.89, SDlower = 1.04, Mupper = 5.98, SDupper = 1.06, F(1, 395) = 0.68, p = 0.41). Thus, the observed effects were not driven by potential differences in perceptions in these domains.

8.3 Discussion

We replicated the main effect of socioeconomic status on evaluations of a minimalist brand by sampling consumers from different social-class groups. This sampling approach strengthened the ecological validity of our effects and complemented the experimental design used in Studies 2–3. In addition, we ruled out the alternative possibility that our observed effect was due to low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers perceiving the brand as more expensive or due to their greater emphasis on price considerations in decision-making.

Moreover, we identified an important moderator, namely considerations of product-usage frequency. Consumers who tended to consider usage frequency had more favorable evaluations of the minimalist brand, regardless of their socioeconomic status.4 This implies that making product-usage frequency salient may be an effective way to improve evaluations of minimalist brands among consumers with low socioeconomic status. We tested this marketing implication in the next study.

9 STUDY 5: FEATURING USAGE FREQUENCY IN MINIMALIST APPEALS

Building on the previous studies, Study 5 tested whether highlighting product-usage frequency in marketing communication (e.g., advertising) could increase the appeal of minimalist brands among consumers with low socioeconomic status (H4). To this end, we targeted consumers with low socioeconomic status, and exposed them to advertisements that either featured product-usage frequency information or did not.

9.1 Method and results

US participants categorized as “lower class” based on household income (below $50,000, as in Study 4; N = 248, Connect US; 40.9% female, Mage = 40.39, SDage = 12.92) were recruited to complete a two-condition (advertisements: control, frequency) between-subjects study. They read about an affordable minimalist brand, Brand M, and viewed its advertisements. The control condition (n = 124) viewed advertisements that featured a minimalist value (e.g., “I only need one jacket”). The frequency condition (n = 124) viewed advertisements that did the same but also featured product-usage frequency information (e.g., “I only need one jacket, I can climb 20 mountains in it”; Supporting Information: Appendix S1). These advertisement stimuli were pretested for their effect on prompting considerations of product-usage frequency (N = 201, Connect US; Mfrequency = 5.96, SDfrequency = 1.30, Mcontrol = 5.54, SDcontrol = 1.40, F(1, 199) = 4.72, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.02). After viewing the advertisements, participants completed brand evaluation measures (“How much do you like brand M?”, “How likely are you to choose Brand M over a brand that you often purchase?”; 1 = not at all, 7 = very much; as in Study 3, averaged to create an index, α = 0.88) and reported demographic information.

An ANOVA of brand evaluation showed that exposure to the frequency (vs. control) advertisements improved evaluation of the minimalist brand among low-socioeconomic status consumers (Mfrequency = 5.64, SDfrequency = 1.10, vs. Mcontrol = 4.92, SDcontrol = 1.25, F(1, 246) = 22.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09), supporting H4. Thus, when targeting consumers with low socioeconomic status, minimalist brands could increase their attractiveness through advertisements that feature product-usage frequency associated with minimalism.

9.2 Follow-up test

Finally, to verify that improved brand evaluations were driven by increased considerations of usage frequency prompted by advertisements, we conducted a follow-up test. A separate sample of participants (N = 205, Prolific US, 43.9% female, Mage = 36.62, SDage = 10.98) viewed either the frequency (n = 103) or the control (n = 102) advertisements and reported to what extent the advertisements made them consider product-usage frequency. They also reported brand evaluations (as in Study 5; α = 0.89), demographic information, including self-reported social class, and baseline tendencies to consider product-usage frequency (kept as a covariate; measured as in Study 4). We found that, moderated by social class, the advertisements indeed exhibited a positive indirect effect on minimalist brand evaluations, mediated by the temporarily increased usage-frequency considerations, even controlling for individuals' baseline tendency to consider this factor. This indirect effect was stronger among low- (vs. high-) socioeconomic status consumers (PROCESS Model 14, 5000 bootstrapped samples, moderated mediation index = −0.06, 95% CI = [−0.127, −0.001]). Detailed analyses are reported in Supporting Information: Appendix S4.

9.3 Discussion

Targeting consumers with low socioeconomic status, Study 5 demonstrated a feasible way to enhance the appeals of minimalist brands: highlighting the association between minimalism and product-usage frequency in advertising. The follow-up test offered further insights by verifying the underlying process through mediation analyses (Zhao et al., 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest a practical marketing strategy to attract consumers with lower socioeconomic status to minimalist brands.

10 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Across studies using real and fictitious minimalist brands, different operationalizations of socioeconomic status, and both attitudinal and incentive-compatible choice measures, we found that consumers with lower socioeconomic status were less attracted to minimalist brands (Studies 1–3). This is because they tended to prefer quantity over quality in daily consumption, a preference inconsistent with minimalism (Study 3). However, this effect was moderated by considerations of product-usage frequency (Study 4). As such, featuring product-usage frequency in advertisements effectively increased the appeal of minimalist brands among low socioeconomic status consumers (Study 5). We ruled out alternative explanations, including the association between minimalist brands and quality-over-quantity value (Study 2), process disfluency (Study 3), and price perceptions (Study 4).

10.1 Contributions

Our research makes several contributions. First, we contribute to the consumer minimalism literature by departing from the focus on individuals' propensity to adopt minimalism as a lifestyle (e.g., Hausen, 2019; Oliveira de Mendonca et al., 2021) or the impact of adopting minimalism on well-being (e.g., Malik & Ishaq, 2023; Shafqat et al., 2023). We instead examine minimalism as a marketing appeal. We demonstrate how, and under what conditions, consumers' socioeconomic status influences their evaluations of minimalist brands. Because socioeconomic status is a crucial and measurable segmentation variable (Coleman, 1983), our findings offer insights into the (mis)alignment between a minimalist brand's positioning and the interests of consumers with different socioeconomic status.

Second, our findings extend research on the relationship between socioeconomic status and sustainable consumption. Previous studies argued that consumers with lower childhood socioeconomic status had more favorable evaluations of sustainable luxury brands because they tended to value cooperation (Kim et al., 2022). While minimalist brands are often perceived as sustainable, we found that consumers with lower socioeconomic status reported less favorable evaluations of minimalist brands because they tended to value consumption quantity over quality. Thus, minimalism might offer a distinctive approach to sustainability, rendering the relationship between consumer socioeconomic status and minimalist brands, as well as its underlying mechanism, different from those regarding other types of sustainable brands. This complexity echoes the notion that the relationship between socioeconomic status and sustainable consumption is highly contingent on context (Kraus & Callaghan, 2016). Our work contributes to the emerging research that strives to uncover this complexity and offer practical guidance for promoting sustainable consumption.

Third, our findings elucidate the relationship between socioeconomic status and quality–quantity preference. Previous research on this topic has focused on food consumption decisions (Baumann et al., 2019; Cheon & Hong, 2017) and associated health concerns (Vinkeles Melchers et al., 2009). We extend this investigation to the domain of brand evaluations. Notably, consumers were not asked to make a quality–quantity tradeoff when evaluating a minimalist brand. Nevertheless, their preference regarding quality–quantity tradeoffs served as a heuristic that guided brand evaluations. Moreover, we observed our effect both when socioeconomic status was objectively measured and when it was subjectively manipulated. This implies that individuals' quality–quantity preferences could stem from the culture associated with the poor (the affluent) and may be induced when individuals are made to experience an inferior (superior) social position.

Finally, we contribute to emerging research on product-usage frequency (Mittelman et al., 2020) and offer practical solutions for minimalist brands based on our findings. We show that considerations of product-usage frequency moderate the relationship between socioeconomic status and the evaluation of minimalist brands. Accordingly, highlighting product-usage frequency could be an effective marketing approach for minimalist brands to attract low socioeconomic status consumers. Our findings echo those of Sun et al. (2021), who observed that highlighting product durability influenced the preference for quality over quantity in a luxury consumption context. Minimalist brands are distinct from luxury brands in that they do not emphasize high prices or high status (indeed, Study 4 ruled out perceived expensiveness as an explanation). However, consumers' evaluations of minimalist brands are related to their general quality–quantity preferences (Study 3). Thus, we extend understanding of how factors regarding product durability and usage frequency influence decision-making in different contexts associated with quality–quantity preferences. Moreover, we note that within their interactive effect with socioeconomic status, usage-frequency considerations positively predicted the evaluation of minimalist brands even among higher socioeconomic status consumers, although to a lesser extent (Study 4). Thus, strategies that highlight product-usage frequency may have wide-ranging effectiveness and should be adopted by minimalist brands.

10.2 Limitations and future research directions

Our research has limitations that indicate directions for future research. First, although we assessed consumers' responses to minimalist brands using attitudinal measures (all studies), an incentive-compatible choice measure (Study 1), and actual purchase experience (Study 4), we adopted a cross-sectional approach. An important question is whether consumers who favor minimalist brands consistently engage in sustainable consumption in the long run. It is possible that supporters of a minimalist brand buy more frequently from the brand, ironically resulting in an increase in consumption that contradicts the values the brand espouses. Conversely, because brands reflect and shape consumers' attitudes and ideologies toward social causes (Badenes-Rocha et al. 2022; Schmitt et al., 2022), minimalist brands may nudge consumers to consume sustainably—not only in their purchases of that brand but also in other consumption situations. This may facilitate the collectivistic pursuit of sustainability. Longitudinal analyses that trace consumers' responses to minimalist brands may offer a fruitful avenue for future research.

Second, we found that consumers' quality–quantity preference mediated our effect, and we ruled out several alternative explanations. However, the relationship between socioeconomic status and minimalist brand evaluations could be multidetermined. For example, consumers with lower socioeconomic status tend to experience lower levels of interpersonal trust (Stamos et al., 2019). This may reduce their trust in brands that encourage minimalism, as it appears to undermine the brand's own profits. Moreover, we note a limitation in the design of Study 3. We measured quality–quantity preference (the mediator) before brand evaluations (the dependent variable), seeking to directly establish an empirical link between socioeconomic status and quality–quantity preference. However, this design could have inflated the mediating effect of quality–quantity preference. Acknowledging this limitation, we defer to future research to further investigate this and other possible mechanisms that explain the relationship between socioeconomic status and evaluations of minimalist brands.

Third, we established the generalizability of our effects by including both United Kingdom and United States participants and by using stimuli across real and fictitious brands. We also identified a boundary condition (moderator) of our effect, which offers practical implications. Nonetheless, we urge researchers to further examine the generalizability and boundary of the effect that we observed. Given that some view minimalism as a “first world issue” (Dopierała, 2017), the level of economic development of a study's focal society should be considered. The participants in our studies varied in socioeconomic status, but they all lived in economically developed countries. Our observed effect may vary as a function of national economic status and cultural orientation. Moreover, future research should explore other strategies to attract low socioeconomic status consumers to minimalist brands, which may promote inclusivity in the minimalist trend and the broader pursuit of sustainability.

Finally, our research focused on a specific aspect of minimalism, reduced consumption and possessions. Future research should examine how other aspects of minimalism (e.g., decluttering, Ross et al., 2021; mindful consumption and esthetic sparsity, Wilson & Bellezza, 2022) can be incorporated into marketing communication. Factors beyond socioeconomic status may influence consumers' responses to different types of minimalist practices and appeals.

10.3 Conclusion

Minimalism is increasingly popular in daily life, popular culture, and marketing communication. However, consumer segments who differ in socioeconomic status respond differently to brands that incorporate minimalism into their marketing communication. Our research represents an initial step to explore whether, how, and when this approach yields desirable effects. Because minimalist brands have the potential to promote sustainability, understanding consumers' responses to minimalist brands imply opportunities to promote sustainable consumption.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank the financial support from the College of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities at the University of Leicester through the College Research Development Fund, and from the School of Business at the University of Leicester through ULSB Research Seedcorn Funding, which were awarded to the first author. The authors sincerely thank the financial support from the Bayes Business School's Pump Priming Research Scheme (606015), which was awarded to the second author. The authors thank the participants at the EMAC 2023 Annual Conference for their thoughtful comments on the earlier version of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1 Overall, Patagonia was less popular than The North Face, chosen by only 36.5% of participants, underlining the need to understand consumer evaluations of minimalist brands.

- 2 At the end of the study, after all the key dependent and confounding measures had been investigated, participants chose a gift card from Patagonia or The North Face as a lottery prize. Unlike in Study 1, however, the participants did not receive any information about The North Face in this study. In hindsight, we realized that this procedure had made the measure less accurate, and thus we did not focus on it in the analyses. We note, however, that as in Study 1, socioeconomic status had a positive indirect effect on brand choice, mediated by brand evaluation.

- 3 One participant did not answer the question about the perceived minimalism of the brand; thus, N = 396 for this variable.

- 4 We note that socioeconomic status did not affect individuals' tendency to consider product-usage frequency (Mlower = 5.96, SDlower = 1.12, Mupper = 5.92, SDupper = 0.96, F(1, 395) = 0.22, p = 0.64), verifying the appropriateness of testing the interaction of these variables.