The persuasiveness of metaphor in advertising

Abstract

Metaphor—drawing a comparison between two seemingly incompatible concepts in an effort to create symbolism—is frequently used in advertising. This study investigates the persuasiveness of metaphor in advertising and the conditions under which the effectiveness of metaphorical advertisements can be leveraged. Across three experimental studies, the results show that mixed emotional appeals (happiness and sadness) versus positive emotional appeals (happiness) can increase the persuasiveness of an advertising metaphor. Furthermore, cognitive flexibility mediates this effect. This study contributes to the literature on metaphor in advertising by showing the benefits of using mixed emotional appeals and establishing the underlying process. Moreover, the findings can be beneficial for marketers in designing effective marketing communication strategies combining mixed emotions with a metaphor.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of metaphor has become an established communication tool used to enhance the persuasiveness of advertising messages (Hatzithomas et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2019; Van Mulken et al., 2014). For example, the hot and spicy Kentucky fried chicken (KFC) campaign by Ogilvy and Mather Hong Kong demonstrates a creative way in which a metaphor is used to emphasize that chicken is fried with chili spices, delivering an explosion of fiery heat in every bite (Griner, 2018). Similarly, Tesla's advertisements show a car with blue sky and white clouds on its surface to demonstrate the benefit of zero-emission electric cars (Dehay & Landwehr, 2019). An important characteristic of a metaphor is that it does not explicitly address the purpose of the advertising message (Lee et al., 2019), enticing consumers to employ more cognitive resources to process advertising information (McQuarrie & Mick, 1992). Finding nonliteral meaning in a metaphor reduces consumer cognitive tension while increasing perception of pleasure (Mac Cormac, 1990), which in turn leads to improved attitude toward the brand and the ad and higher purchase likelihood when compared to advertisements containing literal messages (Jeong, 2008; McQuarrie & Mick, 1992).

While considerable research support the idea that metaphors enhance advertising message persuasion (Ang & Lim, 2006; Van Mulken et al., 2014; Van Stee, 2018), some studies show that this effect is higher among consumers with high need for cognition (Brennan & Bahn, 2006; Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004), with high processing abilities (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009), with a promotion focus versus a prevention focus (Lee et al., 2019), and for males than females (Lagerwerf & Meijers, 2008). Despite the growing interest in understanding the conditions under which metaphors enhance advertising effectiveness, studies on the cognitive mechanism that drives the effect of emotional appeals on advertising metaphor persuasion are limited (Bok & Yeo, 2019; Margariti et al., 2019; Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009).

While marketers have widely employed emotional appeals in advertising (Dooley, 2009; Pham et al., 2013; Poels & Dewitte, 2019), the examination of emotional appeals in advertising has mostly focused on positive emotions (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Poels & Dewitte, 2019; Septianto & Garg, 2021). However, consumers often experience mixed emotions (i.e., negative and positive emotions at the same time) across important events (e.g., wedding day, graduation day; Deng et al., 2016) and common situations (e.g., watching horror movies, listening to music; Heavey et al., 2017). As such, it would be of interest to explore how mixed emotional appeals may increase effectiveness of metaphor in advertising.

Building on prior mixed emotions literature (Hong & Lee, 2010; Quach et al., 2021; Septianto, 2021; Williams & Aaker, 2002), we argue that when individuals experience mixed emotions, such individuals would expand their mental schemas and cognitive scope (Kleiman & Enisman, 2018) to allow for the consideration of multiple alternatives, which in turn facilitates problem solving and decision making (Rothman & Melwani, 2017). Therefore, we hypothesize that a mixed emotions advertising appeal can enhance consumers' cognitive flexibility, helping them to find nonliteral meaning to a metaphor, and resulting in more favourable purchase intentions.

In addition to the practical implications of employing mixed emotional appeals and fostering cognitive flexibility when promoting metaphorical advertisements, this study provides three theoretical contributions. First, our research contributes to the literature on metaphor in advertising by examining the conditions under which it can increase advertising effectiveness. In particular, while past research has investigated the effects of different types of metaphors in advertising (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004, 2009), it remains unclear how emotional appeals can leverage the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. Second, we contribute to the literature on consumer emotions by showing how mixed (vs. positive) emotional appeals can improve advertising persuasion. Such effect has received limited attention in the current literature (Carnevale et al., 2018; Hong & Lee, 2010; Williams & Aaker, 2002) and is yet to be tested in the context of metaphor in advertising. Third, we demonstrate the role of cognitive flexibility in driving the effect of mixed emotions appeal on the persuasion of metaphor in advertising. Past research has argued that metaphors can make imagery processing more salient (Lee et al., 2019; Roy & Phau, 2014), thus encouraging consumers to be more imaginative (Ang & Lim, 2006). In this regard, answering a call by West et al. (2019), we add to the literature on creative advertising by showing how cognitive flexibility can influence consumer decision making for metaphor in advertising, a common creative advertising technique.

The study is organized as follows. First, the relevant literature on metaphor in advertising, mixed emotions, and cognitive flexibility is discussed to develop a theoretical backbone for the proposed hypotheses. Then, results from three experimental studies used to test the research hypotheses are presented. In the final section, theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

2 THEORETICAL DEVELOPMENT

2.1 Metaphor in advertising

Marketers have widely employed metaphor in their advertising and marketing campaigns (Ang & Lim, 2006; Lee et al., 2019). In this study, we define metaphor as “a figure of speech that involves comparison between two objects” (Lee et al., 2019, p. 1175), in which it transfers the features of one object to the other (Sopory & Dillard, 2002). In other words, a metaphor encourages consumers to deduce an analogy between the two objects that can be structurally or physically similar (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004). For instance, Chevrolet used “Like a Rock” campaign to elicit the perceptions of the brand as tough. In this context, Chevrolet sought to draw an analogy that it is unwavering and dependable, like a rock, for its customers (Lloyd, 2018). Hence, metaphor in advertising and marketing campaigns highlight an analogy between two seemingly dissimilar objects and highlight the similarity to persuade consumers (Lee et al., 2019).

Past studies suggest there are several trait-based and state-based factors that can influence consumer evaluations of metaphor in advertising (McQuarrie & Mick, 2003). For instance, Toncar and Munch (2001) found that the use of figurative languages in advertising such as metaphors and puns might increase recall only among audiences with low levels of involvement. In addition, a visual metaphor in advertising also leads to favorable evaluations among consumers with high need for cognition (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004) and high processing abilities (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009). Overall, the findings of this study stream show that consumers have divergent motivations and abilities to process a metaphor, which in turn influence the effectiveness of advertising messages.

Prior research has argued that there are two processing modes through which metaphor in advertising can lead to favorable consumer evaluations. On the one hand, consumers might evaluate advertisements via imagery processing (Lee et al., 2019; Roy & Phau, 2014), which draws from nonverbal, sensory-related information in memory (Childers et al., 1985). Because metaphor in advertising elicits perceptions that the advertised brand or product is imaginative (Ang & Lim, 2006), the information processing associated with a metaphor is likely to be one of mental imagery (Lee et al., 2019; Roy & Phau, 2014). As a result, these studies suggest that a metaphor can leverage advertising effectiveness by arousing imagination among consumers (Ang & Lim, 2006; Lee et al., 2019).

On the other hand, consumers might also evaluate advertisements via analytical-based processing. Because the use of metaphor in advertising implies that the advertisement does not explicitly and directly address a conclusion when communicating to consumers (Lee et al., 2019), consumers are encouraged to interpret and make inferences about advertising meaning in different manners (Ang & Lim, 2006; Toncar & Munch, 2001). Developing several sets of associations among objects enhances cognitive elaboration, leading to a higher persuasion (Sopory & Dillard, 2002). However, given that consumers need some level of processing ability to evaluate a metaphor (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009), we argue that enhancing consumers' cognitive flexibility can boost consumers ability and motivation to make sense of complex information in a metaphor.

This study thus extends previous literature findings by proposing the role of cognitive flexibility in driving the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. Cognitive flexibility refers to individuals' mental ability to process different types of information and to draw links between various concepts (Braem & Egner, 2018; Laureiro-Martínez & Brusoni, 2018). Given that processing metaphor in advertising involves interpreting and making connections of seemingly dissimilar concepts (Lee et al., 2019), we reason that improving cognitive flexibility can encourage consumers to process and evaluate a metaphor more favorably. In the following section, we explicate how a mixed emotions appeal can foster cognitive flexibility, enhancing effectiveness of metaphor in advertising.

2.2 Mixed emotions and cognitive flexibility

Consumers experience mixed emotions when they feel both positive (pleasant) and negative (unpleasant) emotions simultaneously (Larsen et al., 2001). While some researchers have previously suggested that negative and positive emotions do not simultaneously co-occur (Russell & Carroll, 1999), it has been established that consumers can subjectively experience negative and positive emotions jointly in a single event (Carrera & Oceja, 2007; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2010). Notably, consumers might feel such mixed emotions across important events (e.g., wedding day, graduation day; Deng et al., 2016) and even common situations (e.g., watching horror movies, listening to music; Heavey et al., 2017).

A growing body of literature has explored the influence of mixed emotions and the conditions under which mixed emotional appeals can be persuasive. For example, mixed emotions can lead to indulgence (Ramanathan & Williams, 2007) and preferences for self-made goods (Septianto, 2021). Other research also demonstrates that, in the advertising and marketing communication context, eliciting mixed emotions can increase persuasion among consumers with collectivistic (vs. individualistic) cultures (Williams & Aaker, 2002), high (vs. low) construal levels (Hong & Lee, 2010), and a growth (vs. a fixed) implicit mindset (Carnevale et al., 2018). In this regard, most research examining mixed emotions in advertising (Hong & Lee, 2010; Septianto, 2021; Williams & Aaker, 2002) has examined the co-occurrence of happiness and sadness, which are also the focus of this study.

In this study, we aim to extend prior literature by proposing that mixed emotions can enhance cognitive flexibility. This is because mixed emotions are elicited when individuals need to deal with changes occurring in their environment (Rothman & Melwani, 2017; Septianto, 2021). That is, when experiencing mixed emotions, individuals are exposed to conflicting affective information (Hong & Lee, 2010; Septianto, 2021; Williams & Aaker, 2002) and need to consider multiple alternatives when making decisions (Rothman & Melwani, 2017). As a result, stimulating such conflicting information encourages individuals to expand their mental schemas and cognitive scope—hence, an enhanced cognitive flexibility (Kleiman & Enisman, 2018).

Note that this study examines the effect of mixed emotions (happiness and sadness) as compared to positive emotions (happiness alone). We use positive emotions as the comparison condition because such appeals have been frequently used in marketing communication and advertising contexts (Cavanaugh et al., 2015) as well as in academic studies as a comparison condition (Hong & Lee, 2010; Septianto, 2021; Williams & Aaker, 2002).

Taken together, the present research proposes that mixed emotions (vs. positive emotions) can enhance cognitive flexibility. This is because an exposure to mixed emotions (i.e., conflicting affective experience) as compared to a pure affective experience such as positive emotions, encourages individuals to expand their mental schemas and cognitive scope—hence, an enhanced cognitive flexibility (Kleiman & Enisman, 2018). We further argue that cognitive flexibility can increase the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising because processing a metaphor involves interpreting and making connections of seemingly dissimilar concepts (Lee et al., 2019). As such, we argue that mixed emotions (vs. positive emotions) can leverage positive consumer evaluations of metaphor in advertising. However, because cognitive flexibility does not play a significant role in processing nonmetaphorical advertising, we do not expect such differences to emerge when consumers evaluate nonmetaphorical advertising.

In this study, we examine click-through rates as the behavioral measure of consumer evaluations. Using a real behavior rather than behavioral intentions would improve the ecological validity of our findings, consistent with recent trends to scrutinize how we measure consumer behavior (Inman et al., 2018). In this regard, click-through rates have been recognized as a measure of online advertising effectiveness (Can et al., 2021; Fajardo et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2007) and are indicative of consumer purchase likelihood (Kupor & Laurin, 2020; Zhang & Mao, 2016). Formally stated:

H1. There will be a significant interaction between emotion and metaphor in advertising, such that mixed emotions (happiness and sadness) versus positive emotion (happiness) will increase click-through rates for a metaphorical advertisement.

H2. The interaction effect between emotion and metaphor in advertising on click-through rates is mediated by cognitive flexibility, such that mixed emotions (happiness and sadness) versus positive emotion (happiness) will enhance cognitive flexibility, which in turn increases click-through rates for a metaphorical advertisement.

2.3 Overview of studies

We conducted three experimental studies to test our hypotheses. Studies 1 and 2 tested Hypothesis 1, whereas Study 3 tested Hypotheses 1 and 2. We used different contexts to manipulate mixed emotions (graduation in Studies 1 and 2, moving to a new place in Study 3) and different metaphorical product advertisements (camera in Studies 1 and 2, sunblock in Study 3).

In addition, while Studies 1 and 2 manipulated integral emotions (emotions that arise from the context of the decision at hand) using advertising messages, Study 3 examined incidental emotions (i.e., emotions arising from a prior unrelated task) (Lerner et al., 2015) and tested the spillover effect of these emotions (mixed emotions vs. positive emotions) on the evaluation of a metaphorical advertisement. We intentionally tested the context of incidental emotions because such examinations provide empirical evidence with high internal validity (Han et al., 2007). Indeed, prior research has demonstrated that the effects of incidental and integral emotions are consistent (Cavanaugh et al., 2015; Duhachek et al., 2012; Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Septianto & Garg, 2021). As such, by investigating incidental and integral emotions, our findings offered strong empirical evidence to our predictions.

3 STUDY 1

We tested the prediction that the mixed emotions of happiness and sadness (vs. happiness) can increase the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. Graduation was used as the research context (Hong & Lee, 2010; Larsen et al., 2001) to elicit mixed emotions and photographic camera was chosen as a product, as it is common to take pictures in academic graduations.

3.1 Method

Study 1 used a one-factor, two-level (emotion: happiness and sadness [mixed], happiness [positive]) between-subjects design. We gained access to the alumni database of a large public university in Indonesia (N = 1000). We conducted the study in the Indonesian language and back-translated the stimuli and the survey used in the study.

Two camera advertisements were developed where: (a) the narratives were altered to evoke the emotional conditions (Hong & Lee, 2010), and (b) images were adjusted to manipulate the presence of metaphor (Lee et al., 2019). Adapted from Hong and Lee (2010), the narrative for those in the mixed emotion appeal was: “The moment has finally arrived. A chapter in your life is beginning, and another one is ending. You're looking forward to the future and the exciting possibilities it holds. You'll also miss the friends you've made and the good times you've had together. It's such a happy and a sad time that you will never forget.” Meanwhile, those in the positive emotion appeal read: “The moment has finally arrived. A chapter in your life is beginning. You're looking forward to the future and the exciting possibilities it holds. It's such a happy time that you will never forget.” In addition, following Lee et al. (2019), we used a metaphorical advertisement in which the image described the inclusion of an iron shackle conveying that the camera has an excellent image stabilization.

Adopting the procedure from Kupor and Laurin (2020), the database manager randomly chose 1000 active alumni members to receive a WhatsApp message with one of the two advertisements (500 participants for each advertisement). The message contained the designated advertisement and stated that a team of business researchers wanted to gather information on a new camera brand. If participants were interested in finding out more about this brand, they were asked to respond by clicking the link that would direct them to a survey.

In the survey, the participants who opted-in were asked to rate how they felt about the advertisement. Specifically, participants responded to questions about their feelings when evaluating the ad on a 7-point scale (1 = “not at all,” 7 = “very much”): happiness (“happy,” “delighted,” and “joyful;” α = 0.87) and sadness (“sad,” “sorrowful,” and “depressed;” α = 0.84; (Hong & Lee, 2010). Finally, participants were asked to provide demographic information (age and gender) and were then debriefed about the nature of the study. As the dependent variable, we calculated the percentage of participants who clicked on the link and responded to the survey within each advertisement condition.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Emotion manipulation checks

Higher levels of sadness were found in the mixed emotion condition than in the positive emotion condition (Mmixed = 4.13 vs. Mpositive = 1.74, F[1, 31] = 26.81, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.464). However, as expected, the levels of happiness were found to be nonsignificantly different between conditions (Mmixed = 4.89 vs. Mpositive = 5.07, F[1, 31] = 0.17, p = 0.686).

3.2.2 Click-through rates

In total, 33 participants (58% females, Mage = 25.76, SD = 9.61) completed the survey. A χ2 test was used to examine whether there was a significant difference in click-through rates between the two advertising conditions. As predicted, participants evaluating the mixed emotional appeal (24/500 [4.8%]) were more likely to click-through the link than those evaluating the positive emotional appeal (9/500 [1.8%], χ2[1] = 7.05, p = 0.008). These results provided evidence supporting Hypothesis 1.

4 STUDY 2

Study 1 tested the effect of mixed emotions in the case of metaphorical advertisement. However, consistent with Hypothesis 1, we also expected that this effect would only emerge in the metaphorical advertising condition and not in the nonmetaphorical advertising condition. This was because cognitive flexibility would not play a significant role in processing nonmetaphorical advertising. As such, in Study 2, we examined both metaphorical and nonmetaphorical advertising. Further, we recruited participants from a different sample to provide stronger empirical evidence on our prediction.

4.1 Method

Study 2 used a 2 (emotion: happiness and sadness [mixed], happiness [positive]) × 2 (metaphor: present, absent [control]) between-subjects design. We recruited 210 participants in the U.S. from Amazon Mechanical Turk (27% male; Mage = 35.21, SD = 8.78).

Four camera advertisements were developed where the narratives were altered to evoke the emotional conditions (Hong & Lee, 2010) and images were adjusted to manipulate the presence of metaphor (Lee et al., 2019). We used identical narratives as those of Study 1 to manipulate the emotional appeals. In addition, following Lee et al. (2019), we elicit the presence (vs. absence) of metaphor by including (vs. not including) an iron shackle conveying that the camera has an excellent image stabilization. Adapting from Can et al. (2021), we then informed participants that they had the option to go to a website providing information about different camera options for purchase. As the dependent variable, we measured participants' clicks on the link (1 = clicked, 0 = did not click). Finally, participants completed emotion manipulation checks (identical to those of Study 1; happiness: α = 0.95 and sadness: α = 0.96).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Metaphor manipulation check

A separate pretest (N = 80 MTurkers) was conducted in which participants were randomly assigned to evaluate either the advertisement with or without a metaphor. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement about whether the advertisement contained a visual metaphor (i.e., a pictorial analogy), measured on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). As expected, participants evaluating a metaphorical advertisement (M = 5.93) indicated that the advertisement contained a metaphor, as compared to those evaluating a nonmetaphorical advertisement (M = 4.95, F[1, 78] = 11.01, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.124).

4.2.2 Emotion manipulation checks

The results revealed that reported levels of sadness were higher in the mixed emotion condition than in the positive emotion condition (Mmixed = 3.90 vs. Mpositive = 3.22, F[1, 206] = 5.42, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.026). However, the difference in levels of happiness were found to be nonsignificant between conditions (Mmixed = 5.10 vs. Mpositive = 5.31, F[1, 206] = 0.83, p = 0.362).

4.2.3 Click-through rates

We conducted a moderation analysis using PROCESS (Hayes, 2017), a “macro” (computation tool) specifically developed for SPSS that facilitates the calculation of mediation and moderation models, estimating statistical values associated with the proposed model paths (e.g., coefficients, standard errors, t-values or z-values, p-values, and confidence intervals). An important benefit of the PROCESS macro is that it offers pre-determined statistical models that are commonly used in experimental research.

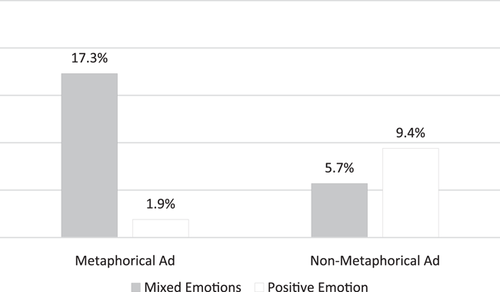

In this regard, we conducted a moderation analysis using PROCESS Model 1 by examining the effects of emotion, moderated by metaphor, on click-through rates. The main effects of both metaphor (B = −0.11, SE = 0.33, z = −0.32, p = 0.749) and emotion (B = 0.45, SE = 0.33, z = 1.38, p = 0.167) were nonsignificant. However, as predicted in Hypothesis 1, there was a significant interaction effect (B = 0.73, SE = 0.33, z = 2.22, p = 0.026).

As can be seen in Figure 1, in the metaphorical advertising condition, participants evaluating the mixed emotional appeal (9/52 [17.3%]) were more likely to click-through the link than those evaluating the positive emotional appeal (1/52 [1.9%], B = 1.18, SE = 0.54, z = 2.20, p = 0.028), supporting our prediction. However, in the nonmetaphorical advertising condition, there were nonsignificant differences across participants evaluating mixed (3/53 [5.7%]) versus positive emotional appeals (5/53 [9.4%], B = −0.28, SE = 0.38, z = −0.73, p = 0.467).

5 STUDY 3

Study 3 had two main purposes. First, it sought to offer strong empirical evidence to Hypothesis 1. Specifically, in addition to using different advertising stimuli, we also investigated the case of incidental emotions, in which emotions elicited by an unrelated task can influence subsequent decision making process (Lerner et al., 2015). As such, we examined the spillover effect of mixed emotions elicited by unrelated advertisements on the evaluations of subsequent metaphorical advertisements. Second, we sought to test the underlying process of cognitive flexibility (H2). Further, because prior research has demonstrated that the extent to which participants are “transported” to an advertisement and able to vividly experience the product can be influential in driving consumer evaluations of mixed emotions and metaphorical advertisements (Lee et al., 2019), this variable was included as a covariate when testing Hypothesis 2.

5.1 Method

Study 3 used a 2 (emotion: happiness and sadness [mixed], happiness [positive]) × 2 (metaphor: present, absent [control]) between-subjects design. We recruited 204 participants in the United States (27% male; Mage = 34.47, SD = 9.18) from MTurk.

Participants evaluated two ostensibly unrelated tasks about advertising evaluations. In the first task, they were randomly assigned to evaluate either an advertisement with a mixed emotional appeal or a positive emotional appeal. Adopted from Williams and Aaker (2002), the ad was about a fictitious moving company (Transportex Movers). Those in the mixed emotions condition read: “The moment has finally arrived. A chapter in your life is ending, but another one is beginning. You'll miss the neighborhood and the friends you've made, but you're also looking forward to the future and the exciting possibilities it holds. It's such a sad and a happy time—you want movers who understand this. Movers you can trust. Let Transportex handle the details—all you have to do is look back on your old life and look forward to your new one!”

In the positive emotion condition, participants read: “You've been looking forward to this moment for so long. A new chapter in your life is just beginning, and the future is full of exciting possibilities. You are looking forward to moving to a new neighborhood and the new friends you'll make. It's a happy time—you want movers who understand this. Movers who will make the move fun. Movers you can trust. Let Transportex handle the details—and all you have to do is enjoy the ride!”

Next, participants completed emotion manipulation checks as in Study 1 by indicating their feelings of happiness (α = 0.87) and sadness (α = 0.94). Cognitive flexibility was measured by asking participants their current feelings about 12 statements (α = 0.84; see Table 1 for the full items), measured on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). This scale was adopted from Martin and Rubin (1995) and has been used by prior research examining the mediating role of cognitive flexibility (Bullard et al., 2019; Herd & Mehta, 2019). The sample of the items include: “I can communicate an idea in many different ways” and “I have many possible ways of behaving in any given situation.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the second task, a metaphorical (present vs. absent) advertisement of a sunblock on a social media was presented to the participants. Following Lee et al. (2019), a visual metaphor was manipulated to ensure that the attribute of the source (sunblock) would transfer to the target (shade). The metaphorical advertisement illustrated how the sunblock acted as a shade, thus protecting the wearers from harmful sunlight. In the nonmetaphorical advertisement, the ad shows that the shade (target) came from an umbrella, thus removing the visual metaphor of the protective nature of the sunblock.

The measurement of the dependent variable was similar to Study 1 where participants rated their intentions to purchase the advertised sunblock. Lastly, the extent to which participants vividly experience the product was measured using three items (α = 0.91) on a 7-point scale (Lee et al., 2019). The items were (1 = “not at all,” 7 = “very much”): “I imagined myself using the sunblock;” “I savored visions of the sunblock;” and “I experienced a sense of fun in thinking about the sunblock.”

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Metaphor manipulation check

As in Study 2, a separate pretest (N = 80 MTurkers) was conducted in which participants were randomly assigned to evaluate either the advertisement with or without a metaphor. As expected, participants evaluating a metaphorical advertisement (M = 5.78) indicated that the advertisement contained a metaphor, as compared to those evaluating a nonmetaphorical advertisement (M = 4.75, F[1, 78] = 12.56, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.139).

5.2.2 Emotion manipulation checks

Higher levels of sadness were found in the mixed emotion condition than in the positive emotion condition (Mmixed = 4.17 vs. Mpositive = 3.29, F[1, 200] = 8.99, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.043). However and as expected, the levels of happiness were found to be nonsignificantly different between conditions (Mmixed = 5.36 vs. Mpositive = 5.41, F[1, 200] = 0.08, p = 0.777).

5.2.3 Click-through rates

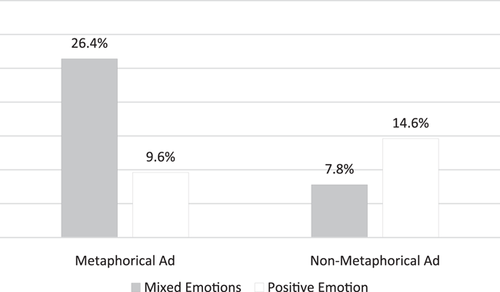

We conducted a moderation analysis using PROCESS Model 1 (Hayes, 2017) by examining the effects of emotion on click-through rates, moderated by metaphor. The main effects of both metaphor (B = 0.24, SE = 0.22, z = 1.11, p = 0.267) and emotion (B = 0.13, SE = 0.22, z = 0.60, p = 0.550) were not significant. However, as predicted in Hypothesis 1, there was a significant interaction effect (B = 0.48, SE = 0.22, z = 2.20, p = 0.028).

As can be seen in Figure 2, in the metaphorical advertising condition, participants evaluating the mixed emotional appeal (14/53 [26.4%]) were more likely to click-through the link than those evaluating the positive emotional appeal (5/52 [9.6%], B = 0.61, SE = 0.28, z = 2.16, p = 0.031), supporting our prediction. However, in the nonmetaphorical advertising condition, there were nonsignificant differences across participants evaluating mixed (4/51 [7.8%]) and positive emotional appeal (7/48 [14.6%], B = −0.35, SE = 0.33, z = −1.05, p = 0.293).

5.2.4 Moderated mediation analysis

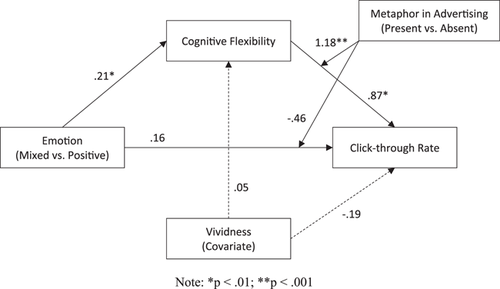

Hypothesis 2 predicted the mediating role of cognitive flexibility in the effect of mixed emotions on purchase intentions for metaphorical advertisement but not for nonmetaphorical advertisement. As expected, cognitive flexibility was higher when participants assessed an advertisement with a mixed emotional appeal than with a positive emotional appeal (Mmixed = 4.87 vs. Mhappy = 4.47, F[1, 200] = 7.98, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.038).

To test the moderated mediation analysis, we used PROCESS Model 15 (Hayes, 2017). Hayes, Montoya, et al. (2017) examined the differences between PROCESS and SEM in testing a moderated mediation model and found that both provide consistent findings. In fact, in the case of relatively small sample size, PROCESS is more beneficial as “SEM is generally regarded as a large sample technique” (Hayes, Montoya, et al., 2017, p. 79). As such, it was appropriate for the present research to test the predicted moderated mediation using Hayes' PROCESS.

The model (PROCESS Model 15 with 5000 bootstrap resamples; see Figure 3) examined the indirect effects of emotion (mixed = 1, positive = −1) on click-through rates via cognitive flexibility, as moderated by metaphor (1 = metaphor, −1 = non-metaphor). We also included the vividness of advertisement (Lee et al., 2019) as a covariate. As expected, the results revealed a significant index of moderated mediation (B = 0.49, SE = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.15 to 1.24), such that a statistically significant indirect effect was found in the metaphorical advertisement condition (B = 0.42, SE = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.15 to 1.12) but not in the nonmetaphorical advertisement condition (B = −0.06, SE = 0.09, 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.09). These findings provided empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

6 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Metaphor is an important communication tool used by advertisers to increase advertising effectiveness (Lee et al., 2019; Van Mulken et al., 2014; Van Stee, 2018). Prior research on this body of literature demonstrates that a metaphor enhances advertising persuasion (Ang & Lim, 2006; Van Mulken et al., 2014) because finding nonliteral meaning on ambiguous advertising messages reduces consumer cognitive tension (Mac Cormac, 1990), leading to more favorable attitudes toward the advertisement. Building on prior emotions literature (Hong & Lee, 2010; Quach et al., 2021; Septianto, 2021; Williams & Aaker, 2002), we have argued that individuals expand their mental schemas and cognitive scope (Kleiman & Enisman, 2018) when experiencing mixed (vs. positive) emotions, which in turn helps them to find nonliteral meaning in advertising metaphors, and result in more favourable purchase intentions. Evidence for our hypotheses was provided across three experimental studies showing that mixed emotions can increase consumer likelihood to purchase a product promoted with a metaphorical advertisement. Further, we show that this effect is mediated by cognitive flexibility, such that mixed emotions enhance cognitive flexibility.

6.1 Theoretical implications

Our research makes important contributions to the literature on metaphor in advertising by highlighting the conditions under which it can increase advertising effectiveness. Literature on this study stream shows that the use of a metaphor enhances consumer receptivity towards advertisement (Hatzithomas et al., 2021; Jeong, 2008; Kim et al., 2012; McQuarrie & Phillips, 2005; Van Stee, 2018), leading to more elaborate information processing (Ahn et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2017; Toncar & Munch, 2001). While there has been great interest in understanding the effects of different types of metaphors in advertising (Chang et al., 2018; Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004, 2009), there has been no research examining how emotional advertising appeals can influence the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. To the best of our knowledge, our research is the first to examine how emotional appeals can be beneficial to increase the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. This is significant given the central role emotions play in the advertising context (Poels & Dewitte, 2019).

Moreover, we contribute to the literature on consumer emotions showing how mixed (vs. positive) emotional appeals can improve advertising persuasion, an examination that has received limited attention in the current literature and was yet to be tested in the context of metaphor in advertising. Even though past research has explored different situations under which mixed emotional appeals can be more effective in increasing positive responses from consumers (Carnevale et al., 2018; Hong & Lee, 2010; Williams & Aaker, 2002), the effects of mixed emotions on consumers psychological state and decision making remain unclear. For instance, some research suggests that mixed emotions versus positive ones may lead to more discomfort and less favourable attitudes (Hong & Lee, 2010; Williams & Aaker, 2002). Other researchers, however, demonstrate that a mixed emotional appeal can lead to more enjoyable advertising viewing (Madrigal & Bee, 2005), more indulgence (Ramanathan & Williams, 2007), enhanced consumer preferences for self-made goods (Septianto, 2021), and increased positive WOM (Quach et al., 2021) when compared to a pure positive emotion.

Adding to this literature, our findings add a more nuanced understanding of how mixed emotions can increase cognitive flexibility, allowing consumers to find meaning in a metaphor, leading to more favorable judgments. This finding is in line with previous research showing that individuals find more satisfaction in experiences that evokes both negative and positive feelings (Bartsch et al., 2008) because people, in general, are fundamentally motivated to find meaning, a sense of purpose, in addition to their pursue to happiness (Baumeister et al., 2013; Heintzelman & King, 2014).

Finally, our research establishes the mediating role of cognitive flexibility in driving the effect of mixed emotions appeal on advertising persuasion. Past research has argued that a metaphor can make imagery processing more salient (Lee et al., 2019; Roy & Phau, 2014), thus encouraging consumers to be more imaginative (Ang & Lim, 2006). However, because consumers are required to have some levels of processing abilities when evaluating a metaphor (Phillips & McQuarrie, 2009; Sopory & Dillard, 2002), it is also important to examine how to encourage such mental state. As such, we contribute to the literature on metaphor in advertising by highlighting an additional intervening variable—cognitive flexibility (elicited by mixed emotions)—that can influence the effectiveness of metaphor in advertising. Furthermore, answering a call by West et al. (2019) for models that capture mental processes that occur when consumers view creative advertisements, we add to the literature on creative advertising by showing how cognitive flexibility can influence consumer decision making for metaphor in advertising, a common creative advertising technique.

6.2 Managerial implications

Advertisers frequently use a variety of appeals to elicit consumer attention. A particularly useful creative tactic used to arouse consumers and elicit cognitive elaboration in advertising is the use of a visual metaphor. Metaphors can prompt a varied range of interpretations by consumers who may perceive ad messages to be incomprehensible at a first glance. This causes arousal, and the interpretation of the message elicits feelings of accomplishment once the message is decoded (Barthes, 1986), which in turn results in a positive attitude toward the ad. However, if consumers cannot find meaning in the metaphor, or if the metaphor is too complex and too hard to comprehend, it can lead to negative outcomes (Dehay & Landwehr, 2019). Therefore, it is important that marketers develop a creative copy that facilitates consumer comprehension of metaphors. In this sense, the findings of our research have direct implications for marketers to develop effective advertising strategies when using metaphorical advertisements. Our research shows that the use of mixed (vs. positive) emotional appeals can help individuals to expand their mental schemas and cognitive scope, which in turn results in more favourable behavioral outcomes (e.g., click-through). Specifically, we provide evidence from three experiments showing that a creative ad copy evoking mixed emotions enhances cognitive flexibility and in turn leads to higher click-through rates for products promoted with a metaphorical advertisement.

Furthermore, the findings of our research provide useful insights to situations when mixed emotions arise naturally (e.g., wedding or graduation day; Larsen et al., 2001; Williams & Aaker, 2002). In this context, we suggest that marketers consider using a metaphor to promote their products and services. From a media placement perspective, marketers can strategically place video advertisements following contents that elicit mixed emotions such as the viewing of horror movies (Andrade & Cohen, 2007). Horror movies often elicit mixed emotions as suspense in drama is often viewed as an experience that elicits feelings of apprehension about the resolution of conflicts. That is, viewers feel fear that something undesirable may happen while hoping for a positive outcome (Madrigal & Bee, 2005). The same rationale can be applied to products that naturally evoke mixed emotions such as snack products. For example, consumers aiming to satisfy their sugar cravings might choose a chocolate bar which often elicit pleasure and guilt feelings, particularly for those consumers aiming at losing or maintaining weight. Advertisers in this industry should consider using metaphors more frequently while exploring the product category's guilt-pleasure associations, enhancing consumers' cognitive flexibility, increasing brand recall and purchase intentions.

Finally, knowing that the effect of mixed emotions is driven by cognitive flexibility, marketers can also seek to foster cognitive flexibility in different ways when promoting advertising messages. For instance, messages with negations have been found to increase cognitive flexibility by promoting openness to new perspectives, helping attitude change toward outgroups (Winter et al., 2021). In the context of political advertising, when designing pro-immigrant campaigns, marketers may consider the use of messages with negations (e.g., “They don't reject the values lived here.”) rather than affirmations (e.g., “They are open to the values lived here.”) to lessen negative attitudes of those who are yet to make up their minds regarding a government's immigration policy.

6.3 Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations that further opens future research avenues. First, the present study only focuses on the mixed emotions of happiness and sadness as they are frequently used in the advertising context (Hong & Lee, 2010; Williams & Aaker, 2002). However, there are different types of mixed emotions (a combination of positive, e.g., relaxed, calm, excited, upbeat, satisfied, and elated) and negative feelings (e.g., fear, stressed, disgust, disappointed, and dissatisfied) and different situations (e.g., having a relationship breakup, moving to a new school or workplace, and participating in an extreme sport such as bungee jumping) under which such emotions can be elicited (Aaker et al., 2008; Andrade & Cohen, 2007). Therefore, it would be important to examine whether our predicted effect would hold across these different types of mixed emotions. Furthermore, previous studies suggested that Easterners (e.g., Asians) tend to experience more mixed emotions than Westerners (Larsen & McGraw, 2011; Williams & Aaker, 2002). Thus, it is important that future research examines how culture may affect the effectiveness of mixed emotions appeals on metaphorical advertising.

Second, our study has only used visual metaphors in advertising as stimuli (Lee et al., 2019; Phillips & McQuarrie, 2004). Future research can extend our findings by examining different types of metaphors, such as puns or verbal metaphors (Toncar & Munch, 2001), while eliciting different emotional states. In addition, the effectiveness of mixed emotional appeals in metaphorical advertising in digital and social media as well as video advertising can be compared with a visual metaphor in print advertising.

Third, this study only uses click-through rates as the main dependent variable. While it measures behavioral outcomes and not simply behavioral intentions, it would be beneficial if future research extends the findings of this study by examining other forms of behavioral proxies; for example, analyzing likes and comments from online content that uses metaphor and mixed emotional appeals (Micu et al., 2017), and/or measuring conversion rates (Zhang & Mao, 2016). Depending on the context of the research, future studies may also consider using actual purchase (instead of purchase intention) as the behavioral outcome.