Fabrication and maturation of integrated biphasic anatomic mesenchymal stromal cell-laden composite scaffolds for osteochondral repair and joint resurfacing

Abstract

Articular cartilage injury can lead to joint-wide erosion and the early onset of osteoarthritis. To address this, we recently developed a rapid fabrication method to produce patient-specific engineered cartilage tissues to replace an entire articular surface. Here, we extended that work by coupling a mesenchymal stromal cell-laden hydrogel (methacrylated hyaluronic acid) with the porous polycaprolactone (PCL) bone integrating phase and assessed the composition and mechanical performance of these constructs over time. To improve initial construct stability, PCL/hydrogel interface parameters were first optimized by varying PCL pretreatment (with sodium hydroxide before ethanol) before hydrogel infusion. Next, cylindrical osteochondral constructs were formed and cultured in media containing transforming growth factor β3 for up to 8 weeks, with constructs evaluated for viability, histological features, and biochemical content. Mechanical properties were also assessed in axial compression and via an interface shear strength assay. Results showed that the fabrication process was compatible with cell viability, and that construct biochemical content and mechanical properties increased with time. Interestingly, compressive properties peaked at 5 weeks, while interfacial shear properties continued to improve beyond this time point. Finally, these fabrication methods were combined with a custom mold developed from limb-specific computed tomography imaging data to create an anatomic implantable cell-seeded biologic joint surface, which showedmaturation similar to the osteochondral cylinders. Future work will apply these advances in large animal models of critically sized osteochondral defects to study repair and whole joint resurfacing.

1 INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common degenerative joint condition in the United States.1 In addition to OA in older patients who often require total joint replacement, full thickness cartilage defects are present in the knees of as many as 36% of younger athletes.2 While some biologic, joint-sparing treatments do exist, such as osteochondral transfer and matrix-assisted autologous chondrocyte implantation,3-5 their efficacy and long-term durability in large defects are either limited or unknown.6 To address this, the field of tissue engineering has developed functional implants that might be used for cartilage repair. Over the past several decades, a myriad of constructs have been studied that vary in shape (simple vs. anatomic), size (partial articular vs. complete), manufacturing method (mold vs. three-dimensional [3D]-printed), structure (monophasic vs. multiphasic), material (devitalized tissue vs. synthetic), cellularity (acellular vs. cell-seeded), and cell type (mesenchymal stromal cell [MSC] vs. chondrocyte). The combined efforts of the field have resulted in the ready production of engineered tissues that match many aspects of the biochemical, histological, and, most importantly functional properties of native tissue.7-11

As the engineered tissue grown in the laboratory more closely approximates that of native tissue, the field has begun to consider the practical translation of these engineered constructs into the in vivo space. In particular, a number of investigators have generated osteochondral and/or anatomic engineered implants that could provide biologic restoration of joints with severe, late-stage OA.12-23 Towards that end, we developed a system, based on rapid-prototyped 3D printed molds generated from patient-specific computed tomography (CT) scans.24 Still more recently, we extended this study to include a molding strategy that generates osteochondral hydrogel/porous PCL units that can be implanted to completely replace an entire articular surface, inclusive of the subchondral bone.25 That prior work represented only a proof of concept, however, given that it included a hydrogel alone—without cells to provide for sustained matrix production and functional maturation.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to couple a cell-seeded hydrogel (methacrylated hyaluronic acid, MeHA) with the porous polycaprolactone (PCL) bone integrating phase. Constructs were first generated as cylindrical units, and hydrogel penetrance into the PCL phase was optimized via base treatment of the PCL. Next, living osteochondral cylinders were formed with bone marrow-derived MSCs in the “cartilage” layer, and their viability and matrix elaboration were evaluated. Overall construct mechanical properties were evaluated in compression and shear and compared with cell-free controls. We hypothesized that MSCs would remain viable in these composite scaffolds, and deposit matrix over time in culture, enhancing the shear and compressive properties of these constructs in comparison to acellular controls. Finally, we tested whether this approach could be extended into an anatomic context and generated and matured osteochondral constructs representing the full articulating surface of a large animal joint. Together, this study advances the field of osteochondral tissue engineering and biologic joint replacement and sets the stage for large animal translation.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 MeHA synthesis

MeHA was synthesized as described previously.26 Briefly, hyaluronic acid (HA) was dissolved in distilled water at 1% wt/vol and placed on ice in a round-bottom flask with stir bar. For each 2 g of HA, 5.94 ml of methacrylic anhydride (Sigma Aldrich) was slowly added to the HA solution over the course of 8 h while maintaining pH at 8.5–9. The solution was then removed from ice and allowed to stir vigorously at room temperature overnight to allow any unreacted methacrylic anhydride to degrade. The solution was then dialyzed against distilled water for 1–2 weeks, lyophilized, and stored at −80°C.

2.2 MSC isolation and culture

Juvenile bovine bone marrow-derived cells were isolated from distal femur and proximal tibia cancellous bone (Research 87).27 MSCs were subsequently expanded in basal media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM] with 10% fetal bovine serum; ThermoFisher) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (PSF; ThermoFisher) until passage 1 or 2, and were stored frozen at −80°C until use. For cell-seeded constructs, passage 3 MSCs were trypsinized (ThermoFisher) and mixed with MeHA at 20 million cells/ml before casting. Constructs were then grown in chemically defined media (high-glucose DMEM, 1% PSF, 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 100 µg/ml sodium pyruvate, 40 µg/ml l-proline, 50 µg/ml ascorbate 2-phosphate, insulin-transferrin-selenium supplement [6.25 µg/ml insulin, 6.25 µg/ml transferrin, 6.25 ng/ml selenous acid, 1.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 5.35 mg/ml linoleic acid]) supplemented with 10 ng/ml transforming growth factor (TGF)-β3 (R&D Systems).

2.3 Construct fabrication

Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) was dissolved in chloroform at 20% wt/vol and mixed with NaCl crystals sieved to ~106 μm.28 The slurry was poured into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) cylindrical mold (height: 3.5 mm, diameter: 5 mm) and the solvent was evaporated. PCL units were then salt-leached in distilled water overnight, followed by pretreatment with NaOH (for some groups), followed by sterilization in ethanol. One percent MeHA was combined with 0.05% lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) crosslinker, and pipetted into an array of cylindrical (diameter: 5 mm) PDMS casting wells (~50 µl/well). PCL units were then suspended (upside down) within the PDMS casting wells containing the MeHA solution, and constructs underwent UV-crosslinking for 10 min using a 365 nm BlakRay UV lamp (#UVL56). The wavelength range was 320–400 nm with a transmission maximum of 70% at 365 nm. To produce cell-seeded constructs, juvenile bovine MSCs (passage 3, described above) were suspended (20 × 106 per ml) in the MeHA solution before cross-linking. Cell-seeded hydrogel–PCL constructs were then transferred to chemically defined media supplemented with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 (10 ml of media per construct) and cultured for up to 8 weeks, with media changed two to three times weekly.

2.4 PCL pretreatment with EtOH and NaOH

After salt-leaching, PCL units underwent 0-, 15-, or 30-min exposure to 1 M NaOH, followed by sterilization in either 70% or 100% ethanol for an additional 2 h. The effect of NaOH pretreatment on contact angle was observed after pipetting ~70 µl water droplets onto the PCL surface. To better visualize and quantify the hydrogel–PCL interface, and the extent to which the HA solution entered into the PCL, hydrogel–PCL constructs were created using 1% MeHA (without cells) with the addition 20 µM methacrylated rhodamine (MeRho). MeRho was permanently crosslinked to the HA backbone during UV polymerization. Constructs then underwent mechanical shear testing as described below. Constructs were imaged at ×4 on an A1R confocal laser microscope (Nikon Instruments) in multiple focal planes (~5 × 20 µm Z-steps) using NIS-Elements advanced research software, and maximum projection images were compiled using Fiji. Hydrogel intensity (maximum gray value) and interface width were then determined using the “Plot Profile” function in Fiji.

2.5 Live/dead assay

Constructs (n = 5) at 8 weeks were diametrically halved, labeled with Calcein-AM (live), Ethidium Homodimer-1 (dead), and Hoechst, and imaged using a confocal microscope (as described above). Maximum projection images were again compiled from multiple focal planes using Fiji.

2.6 Matrix staining and biochemical quantification

Following the live/dead assay, constructs (n = 5) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher) overnight at 4°C, then incubated in Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek) with 30% sucrose at 4°C for 2 days. Samples were then snap frozen and immediately embedded in OCT before sectioning at 50 µm (Leica CM1950; Wetzlar Germany) using Kawamoto's Film.29 Following cryosectioning, sections were adhered to slides using chitosan film adhesive solution (diluted 1:3) and stained with Safranin O/Fast Green (H2O [1 min], 0.05% Fast Green [1 min, Sigma Aldrich], 1% acetic acid [30 s], 0.2% safranin-O [2 min], H2O [5 min]) or Alcian blue or Picrosirius red as described previously.28 Slides were then mosaic-imaged on an Eclipse 90i (Nikon Instruments Inc.) upright microscope at ×4 and white-balanced to remove background. In additional samples at each time point (n = 9–18 per timepoint), the dimethylmethylene blue dye binding assay30 and orthohydroxyproline assay25 were used to determine glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content and collagen (COL) content following 48–72 h 100 µg/ml proteinase K (Roche) digestion at 60°C.

2.7 Mechanical testing

Thickness and diameter of acellular and cell-seeded constructs were measured, followed by unconfined compression testing or a shear ramp to failure test. Hydrogels were separated from PCL constructs before compression testing. Compression testing consisted of (1) ramp to 0.2 N; (2) stress relaxation to 10% strain; and (3) and dynamic compression (1% strain at 0.5 Hz) performed in a 1× PBS bath at room temperature. Interfacial properties were assessed using a custom testing device, based on a previously published design.31 A shear ramp displacement at 0.5 mm/s was applied until failure, with the initial start position of the platen located just adjacent to the PCL/hydrogel interface. In a separate set of studies, unconfined compression testing of PCL foams (pre and posttreatment) was performed using a ramp to 30% strain at 1% strain/s. The linear modulus was determined by applying a least-squares bilinear fit to the stress–strain curve from 0% to 30% strain, yielding “toe” and “linear” regions. The slope of the “linear” region is reported as the bulk linear modulus.

2.8 Anatomic accessory carpal (AC) bone implant design and fabrication

To demonstrate the feasibility of generating an anatomic osteochondral construct, molds were produced as described previously.25 In brief, a clinical CT image of a skeletally mature Yucatan minipig forelimb (institutional animal care and use committee approved) was obtained with a portable eight-slice CT scanner (CereTom, Neurologica). The accessory carpal bone was then segmented using ITK-SNAP, exported as a mesh and smoothed in MeshLab (ISTI); and then converted into a 3D object using SolidWorks (Dassault Systèmes). A 500 µm cartilage “shell” was created over the object's surface, and positive molds of both the “bone-only” and “bone-cartilage-composite” surfaces were 3D-printed. Sylgard-184 (PDMS) was used to fabricate negative molds from the 3D-printed positive molds. PCL (dissolved in chloroform with salt crystals, as described above) was then added to the “bone-only” PDMS negative mold to create the anatomic PCL “bone” portion. MSC-seeded MeHA solution with LAP crosslinker was then applied to the “bone-cartilage-composite” PDMS negative mold, and the salt-leached anatomic PCL “bone” was placed on top (similar to PCL “plugs” in Figure 1) followed by UV-crosslinking. The resulting anatomic hydrogel–PCL constructs were then transferred to chemically defined media supplemented with 10 ng/ml TGF-β3 (with an ample 10 ml of media per construct32) and cultured for 6 weeks, with media changes three times weekly.

2.9 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R version 3.6.2. Effects of varying EtOH and NaOH pretreatments were assessed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Tukey honest significant difference (HSD) tests, if effects were found to be significant. Comparison of acellular and 8-week cell-seeded constructs was performed using two-tailed Student's t tests. The effect of culture time (weeks) on construct biochemical content and mechanical properties was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey HSD tests if the effect was found to be significant. Significance was defined as p < .05.

3 RESULTS

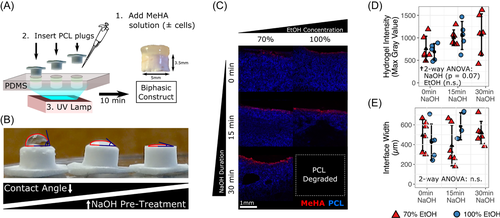

Biphasic “osteochondral” scaffolds were created by placing PCL foam cylinders in a PDMS mold array in conjunction with a MeHA solution. After each unit was crosslinked for 10 min via exposure to ultraviolet light, individual units could be removed from the molds (Figure 1A). During pilot testing, it was noted that the hydrophobic surface of the salt-leached PCL was not compatible with entrance of the aqueous HA solution. To overcome this limitation, a number of pretreatments were assessed to chemically modify the surface. Pretreatment with NaOH resulted in a marked decrease in water contact angle and a greater predilection for fluid uptake (Figure 1B). To fully quantify how PCL pretreatment with NaOH (contact angle) and ethanol (required for sterilization) might affect the properties of the PCL–hydrogel interface, a number of conditions were evaluated. PCL foam cylinders were pretreated with either 0, 15, or 30 min of NaOH, followed by 2 h of exposure to either 70% or 100% ethanol. After pretreatment, MeHA solution spiked with 20 µM MeRho (to aid in visualization) was added to form biphasic constructs (Figure 1C). The hydrogel cap was then sheared off, leaving only the PCL and any MeHA/MeRho that had infiltrated into the PCL at the PCL/hydrogel interface during crosslinking. Hydrogel infiltration was quantified using maximum projection images obtained via confocal microscopy, which identified a trend for longer duration of NaOH pretreatment resulting in increased hydrogel infiltration (p = .07) according to fluorescent intensity (Figure 1D), but not by interface width (Figure 1E). Of note, the 30 min NaOH-100% ethanol group could not be imaged due to the loss of PCL structural integrity.

To further explore the effects of NaOH and ethanol pretreatment on PCL–hydrogel interface integration, a custom ramp-to-failure device was used to measure the shear strength and energy to failure during orthogonal loading of the PCL–hydrogel (acellular) interface (Figure 2A,B). No significant differences in shear strength or energy to failure were noted with varying ethanol pretreatment concentration (Figure 2C,D). However, NaOH pretreatment resulted in a trend toward a greater energy before shear failure (p = .08). Because NaOH may hasten PCL degradation, the effect of combined NaOH and ethanol pretreatment on PCL compressive mechanics was also evaluated. In the group that received 100% ethanol, concomitant with pretreatment for 30 min with NaOH, there was significant weakening of the PCL foam, including a decreased linear modulus (161.2 ± 104.9 kPa [100%] vs. 1894.2 ± 209.8 kPa [70%], p < .001) and a decreased stress at 30% strain (108.2 ± 29.9 kPa [100%] vs. 409.7 ± 81.3 kPa [70%], p < .001) compared with pretreatment with 30 min NaOH and only 70% ethanol. The linear modulus also decreased in the 100% ethanol group (compared with 70%) after only 15 min NaOH pretreatment (1164.8 ± 43.3 kPa [100%] vs. 1761.5 ± 370.1 kPa [70%], p = .005). From these data, we concluded that NaOH pretreatment may be safely followed by a 2-h sterilization in 70% ethanol. We further concluded that 2-h sterilization in 100% ethanol maintains construct integrity, so long as it is not combined with NaOH pretreatment.

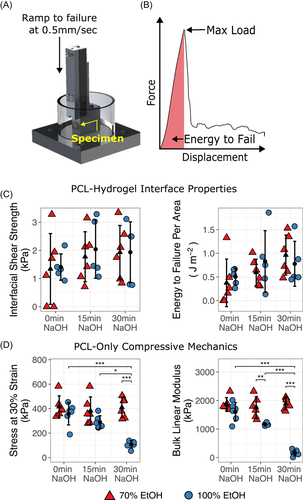

Next, biphasic PCL–hydrogel constructs seeded with juvenile bovine bone marrow-derived MSCs (20 million cells/ml) were created and cultured for 8 weeks in media supplemented with TGF-β3. Constructs were harvested at regular intervals for the assessment of histologic and biochemical composition as well as compressive and shear mechanics (Figure 3). Live/dead imaging at 8 weeks demonstrated cell viability throughout the construct, with subjectively higher viability in the gel periphery (Figure 3A). Decreased PG staining (but increased COL staining) was also observed in the hydrogel center compared with the periphery. Mean GAG content as a proportion of wet weight was 3.6 ± 0.6% (Figure 3B). Mean thickness was similar after 8 weeks of culture for cell-seeded (2134 ± 337 μm) and acellular constructs (2179 ± 198 μm), though the gel diameter of cell-seeded constructs was greater (4.8 ± 0.2 mm vs. 3.7 ± 0.3 mm, p < .001). Dynamic modulus increased significantly by 8 weeks compared with acellular constructs (493.9 ± 149.8 [cell-seeded] vs. 26.5 ± 6.2 kPa [acellular], p = .008) (Figure 3C), with a similar trend for equilibrium modulus (p = .07) (Figure 3D). Interfacial shear strength (148 ± 61 vs. 1.2 ± 0.7 kPa, p = .002) and energy to shear failure per area (117.3 ± 77.3 vs. 0.3 ± 0.2 J m−2, p = .01) were also greater after 8 weeks of culture compared with acellular constructs (Figure 3E,F).

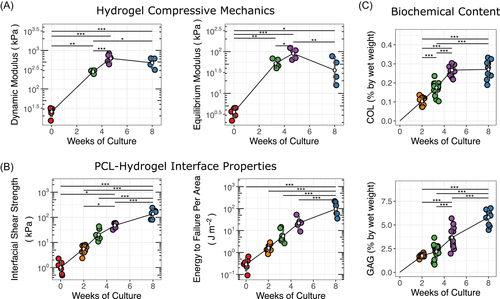

To better characterize the growth trajectory of these constructs, we next evaluated the time-dependent changes in shear and compressive properties as well as biochemical content to judge when such constructs might be durable enough for implantation. To that end, additional constructs were created and cultured in media supplemented with TGF-β3. These constructs were harvested at regular intervals through 8 weeks of culture, with compressive and shear mechanics as well as GAG and COL content assessed at these time points. Compressive and shear mechanics and GAG and COL content all increased significantly over time (Figure 4). However, whereas gains in compressive equilibrium and dynamic moduli had begun to level off after 5 weeks of culture, the interfacial shear properties (including interface shear strength and energy until failure) continued to increase through 8 weeks (p < .001). Similarly, improvements in COL content also appeared to level off after 5 weeks of maturation, while the GAG content continued to increase through the culture duration (p < .001).

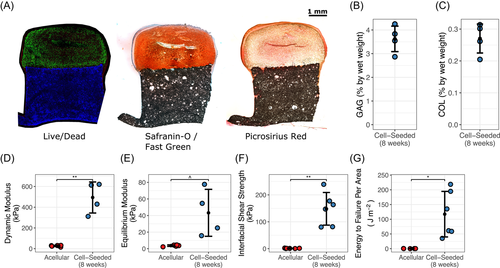

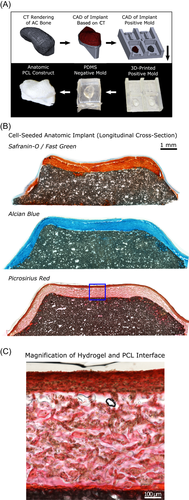

Lastly, to demonstrate the feasibility of creating living, biologic joint replacement constructs, we used CT data to create a 3D reconstruction of the accessory carpal bone (analogous to the trapezium bone in humans) of a Yucatan minipig forelimb. These data were further processed to create anatomic PDMS “bone-only” and “bone-cartilage” composite negative molds (Figure 5A). Using these molds, in combination with the techniques developed in our simplified cylindrical model, we created an anatomic PCL–hydrogel osteochondral “replacement” for the porcine accessory carpal bone. The resulting construct was cultured for 6 weeks in media supplemented with TGF-β3. Safranin-O and Alcian blue staining demonstrated abundant GAG deposition after 6 weeks of culture as well as COL staining throughout the depth, as visualized by Picrosirius red (Figure 5B), validating the potential of this technology for generating constructs for biologic joint replacement.

4 DISCUSSION

Complete “biologic” joint replacement using an anatomic, patient-specific osteochondral implant remains an elusive goal of tissue engineering. Although previous studies have explored various strategies for fabricating cartilaginous joint surfaces, many of these either focused on the cartilage component alone (rather than the osteochondral unit as a whole),24 or alternatively, assessed compressive mechanics alone33, 34 without also considering the bone–cartilage interfacial shear loads that are also present during in vivo loading conditions. We hypothesized that biphasic “osteochondral” PCL–hydrogel scaffolds could be created using MeHA seeded with juvenile bovine bone marrow-derived MSCs within a PDMS mold, and that both compressive and shear mechanics of the resulting constructs would continue to improve over time. Findings from this study showed that both compressive and shear mechanics of constructs improved with greater time in culture. However, whereas improvements in compressive properties began to “level off” after 5 weeks of culture, shear properties continued to increase until study termination at 8 weeks. Notably, the interface shear strength levels seen here reached one order of magnitude greater than that observed in a previous trabecular bone-agarose model of an osteochondral unit.31

During the development of this molding process, we noted that both NaOH and EtOH pretreatment impacted the mechanics and gel infiltration of the PCL substrate. Whereas some NaOH exposure did appear to increase hydrophilicity of the PCL surface—as expected35, 36—excessive EtOH exposure caused irreversible degradation of the PCL foam. Future studies utilizing ethanol as a sterilization method must take steps to account for these effects, such as by ensuring that sterilization is standardized and included in the putative fabrication process of all scaffolds, regardless of whether or not sterility is actually required for the particular scaffold property being studied.

In initial studies, spanning 8 weeks of culture, we observed greater cellularity and GAG in peripheral regions, which perhaps could have been driven by the greater nutrient supply at these locations.24 This is consistent with other studies by our group37, 38 and others39 that note substantial variation in biochemical content across the expanse of thick chondral and osteochondral constructs. We used an optimized volume of media that we and others recently reported can mitigate the spatially varying differences in matrix accumulation.32, 40 This may be further enhanced by additional interventions including culture on an orbital shaker41, 42 or introduction of conduits or channels within the construct.38, 43 Despite some variation in matrix staining across the construct, by week 8, the extracellular matrix that was deposited provided substantial resistance against compression and shear failure. The mechanical properties observed here agree with our previous findings with MSC-laden 1% MeHA hydrogels at similar time points,44 suggesting that the PCL layer did not overtly impede construct maturation. However, it will be important to assess these properties in detail, given that the increasingly robust anchorage of the hydrogel layer to the PCL layer provides a physical constraint at this boundary, which can impact measured mechanical properties in compression.45

In comparing construct growth trajectories using mechanical and biochemical metrics, we were intrigued to note that shear properties and compressive properties did not follow the same growth pattern. That is, the shear strength and energy to failure properties continued to improve with culture duration, beyond a point at which increases in compressive mechanical properties had already begun to level off (Figure 4). In terms of identifying the source of construct shear strength, we initially had hypothesized that COL deposition throughout the hydrogel and at the hydrogel/PCL interface would be the driver of this measure. As such, we expected that the trajectory of increases in COL content would mirror what was seen for shear properties—that is, continue to increase through 8 weeks. Contrary to this hypothesis, when we compared the differences in biochemical content between 5 and 8 weeks, we observed the opposite trend. That is, we found that the change in COL content had leveled off in this time period, while the increase in GAG content continued unabated, and mirrored the continued increase in shear properties between 5 and 8 weeks. Thus, we conclude that although COL deposition is certainly an important determinant of shear strength, GAG content also plays a role, potentially via increased opportunity for interdigitation with the underlying PCL “bone” layer. Future studies will use our recently developed functional noncanonical amino acid tagging and noncanonical sugar GAG labeling methods to produce the local time varying changes in these matrix constituents throughout the gel layer and at the forming osteochondral interface.46

In the practical application of our engineered constructs, successful integration of the bone–bone and cartilage–cartilage interfaces are important considerations that were not explicitly studied here. However, using a similarly engineered porous PCL-based bone-integrating construct in the spine, we recently showed that over the course of several weeks the porous material was successfully infiltrated by cells from the adjacent bone marrow that deposited collagenous material and mineralized this tissue.28 Likewise, with regard to cartilage–cartilage integration in current clinical practice, the process of autologous osteochondral transplantation is regularly utilized, where osteochondral units are implanted into a defect site, similar to the intended use of the engineered constructs developed in this study. Those studies have shown that although the cartilage of the implanted construct remains hyaline-like, the cartilage–cartilage interface exhibits a fibrocartilage-type union.47, 48 The formation of fibrocartilage-type tissue at the cartilage–cartilage interface at the osteochondral transplantation site remains an unsolved clinical and scientific challenge and will require further study and optimization.

While these results represent a significant advance in osteochondral tissue engineering, the study was not without limitation. First, although juvenile bovine MSCs are readily available and can be reliably made to differentiate toward a chondrogenic lineage,27 eventual in vivo testing of this technology in an animal model (such as the Yucatan minipig),49 and future translation into human trials will require species-specific cell sources. MSCs do offer advantages over chondrocytes in terms of minimization of donor site morbidity as well as the relative abundance of bone marrow as a cell source; however, it is possible that MCSs from other species or from donors of advanced age may not respond to chondrogenic cues as readily as these juvenile bovine MSCs.42, 50 Should this be the case, then alternative cell sources (e.g., chondrocytes harvested from articular cartilage) may need to be explored for future in vivo experimentation. In addition, although our custom shear and unconfined compression devices were well suited for the study of simplified cylindrical units, additional work is needed to further develop these techniques for assessing the mechanical integrity of anatomic constructs with more complex geometries. This would be necessary to determine the growth trajectory of future anatomic constructs and confirm their readiness for in vivo implantation. Similarly, future work should incorporate more complex tissue gradients, including the portion of the native osteochondral unit that is calcified cartilage and provides an important gradient in stiffness across this interface; this layer was not included in our initial biphasic model. Future development of this model may benefit from recent magnetics-based approaches that can be used to recapitulate such complex tissue gradients.51 Future work might also seek to limit variation in outcomes among construct cohorts, which may be related to variations in the cell seeding process or from the variable degree of material degradation that occurs as part of the PCL pretreatment process. Despite these limitations, the relative ratio of the standard deviations to the means (~1/3) observed here are similar to previous reports.52 Finally, although mechanical properties were assessed at multiple time points in this study, future work might better characterize how scaffold composition and morphology develop over time, incorporating histological analyses at additional time points.

Taken together, results from this study showed that MSCs could be reproducibly encapsulated in an HA hydrogel/PCL osteochondral composite scaffold, and that mechanical properties matured over time, reaching peak compressive resistance at a time when hydrogel/PCL interfacial shear strength is still continuing to develop. These methods were then successfully leveraged against patient-specific imaging data to create an implantable anatomic cell-seeded biologic joint surface. Future work will continue to explore the application of these methods in large animal models for treatment of critically sized osteochondral defects and whole joint resurfacing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This worked was supported by the Department of Veterans' Affairs (I01 RX003375 and IK6 RX003416), and the NIH/NIAMS (R01 AR056624, T32 AR007132, and P30 AR069619).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to the research design, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; assisted in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically; and have approved the submitted and final versions of the manuscript.